Background: Inhibitors of biotin protein ligase potentially represent a new antibiotic class.

Results: Biotin triazoles inhibit the BPL from Staphylococcus aureus but not the human homologue.

Conclusion: Our most potent inhibitor shows cytotoxicity against S. aureus but not cultured mammalian cells.

Significance: This is the first report demonstrating selective inhibition of BPL.

Keywords: Antibiotics, Biotin, Enzyme Inhibitors, Medicinal Chemistry, X-ray Crystallography, Biotin Protein Ligase

Abstract

There is a well documented need to replenish the antibiotic pipeline with new agents to combat the rise of drug resistant bacteria. One strategy to combat resistance is to discover new chemical classes immune to current resistance mechanisms that inhibit essential metabolic enzymes. Many of the obvious drug targets that have no homologous isozyme in the human host have now been investigated. Bacterial drug targets that have a closely related human homologue represent a new frontier in antibiotic discovery. However, to avoid potential toxicity to the host, these inhibitors must have very high selectivity for the bacterial enzyme over the human homolog. We have demonstrated that the essential enzyme biotin protein ligase (BPL) from the clinically important pathogen Staphylococcus aureus could be selectively inhibited. Linking biotin to adenosine via a 1,2,3 triazole yielded the first BPL inhibitor selective for S. aureus BPL over the human equivalent. The synthesis of new biotin 1,2,3-triazole analogues using click chemistry yielded our most potent structure (Ki 90 nm) with a >1100-fold selectivity for the S. aureus BPL over the human homologue. X-ray crystallography confirmed the mechanism of inhibitor binding. Importantly, the inhibitor showed cytotoxicity against S. aureus but not cultured mammalian cells. The biotin 1,2,3-triazole provides a novel pharmacophore for future medicinal chemistry programs to develop this new antibiotic class.

Introduction

Since the discovery and development of penicillin more than 70 years ago, society has grown accustomed to rapid and effective treatment of bacterial infections. Although a range of antibiotics has since been developed to target a wide diversity of infectious agents, resistance to these compounds is an inevitable and relentless process. The combination of over-prescription and the waning interest of the pharmaceutical industry in this area over the last 30 years has contributed to the emergence of wide spread life-threatening infections with strains that are resistant to most if not all antibiotics in current clinical use (1, 2). For example, Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in the United States has almost trebled in the past 20 years, with 50–60% of hospital-acquired infections now due to methicillin-resistant strains (MRSA) (3, 4). More disturbingly, although the public profile of serious S. aureus infections is that they are hospital-acquired, it is important to recognize that 60% of such infections are now thought to begin in the community (3, 4).

Screening for antimicrobial activity in natural product extracts identified the majority of the currently prescribed classes of antibiotics. The molecular targets for these agents, where known, are generally an essential protein or enzyme that is unique to the prokaryotic pathogen. These obvious drug targets have now been extensively investigated. Because only three new classes of antibiotic have been developed for the clinic in the last 35 years, it is clear that alternative avenues to antibiotic discovery must be considered. One such approach is to target essential proteins and enzymes even if they have homologues in humans. This greatly increases the opportunity to identify new classes of antibiotics with novel modes of action. Importantly, this absolutely necessitates that very high selectivity for the bacterial enzyme is achieved over the human equivalent. A number of antivirals have been identified using this approach, with multiple neuraminidase inhibitors available that have a therapeutic window of >5 orders of magnitude (5, 6).

Biotin protein ligase (BPL)6 presents one such antibacterial drug target. Although it is ubiquitously found throughout the living world, protein sequence comparisons show that this enzyme family is segregated into three structural classes. Importantly, the Gram-negative and Gram-positive pathogenic bacteria fall into class I or II, whereas the enzymes from mammals are in a separate class (III) with a large N-terminal extension required for catalysis that is not present in the bacterial enzymes (7, 8). BPL catalyzes the ATP-dependent addition of biotin onto specific carboxylases that require the cofactor for activity. The BPL in S. aureus (SaBPL) has two such substrates, acetyl-CoA carboxylase and pyruvate carboxylase, that without biotinylation are totally inactive. We and others have proposed BPL as a potential antibacterial target, as acetyl-CoA carboxylase is required for membrane lipid biosynthesis (9–11). This metabolic pathway is important in S. aureus, as the bacteria can only derive 50% of their membrane phospholipids from exogenous fatty acids (12). Inhibitors of bacterial acetyl-CoA carboxylase have demonstrated in vivo efficacy in an S. aureus infection model of mice (13). Pyruvate carboxylase plays an anaplerotic role in central carbon metabolism where it replenishes the tricarboxylic acid cycle with oxaloacetate (14). The inhibition of BPL, therefore, targets both fatty acid biosynthesis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle pathways. Genetic studies support the observation that SaBPL is an essential gene product in S. aureus (15–17).

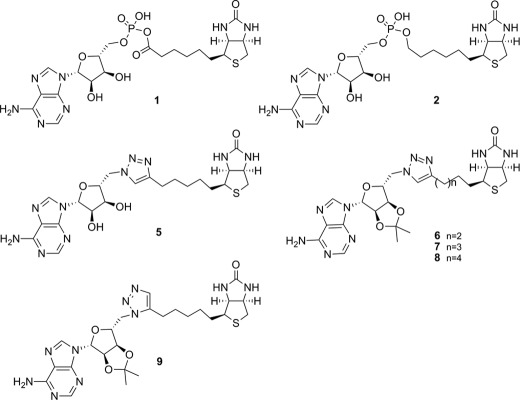

BPL performs protein biotinylation via the synthesis of a reaction intermediate, biotinyl-5′-AMP (1, Fig. 1), where a labile phosphoanhydride linker joins biotin with AMP. An enzymatic mechanism involving an adenylated intermediate is employed by other organic acid ligases, such as aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, o-succinylbenzoyl-CoA synthetase, and phosphopantothenoylcysteine synthetase, among others. Using an adenylated intermediate as a basis for developing ligase inhibitors is problematic because of the hydrolytic and enzymatic instability of the component phosphoroanhydride linkage and difficulties of synthesis (18). Nonetheless, several of these enzymes have been the subjects of antibacterial drug discovery studies using inhibitors designed to replace the labile phosphoanhydride with more stable functionalities (19–24). Non-hydrolysable phosphate bioisosteres, such as sulfonyl, phosphodiester, hydroxylamine, and di-keto-ester, have been reported. However, there has been limited success in developing inhibitors that show the required selectivity over the mammalian homologues. This was highlighted in a recent study targeting the BPL from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (11) using a simple analog of the reaction intermediate 1 where the phosphate linker was replaced with a sulfamate group. Although the acylsulfamate analog was a potent inhibitor of M. tuberculosis BPL (KD 0.5 nm), it was not tested for its selectivity in vitro with human BPL. However, observed toxicity in a cell culture model suggested poor selectivity. Thus the development of antibiotics based on the inhibition of BPL requires compounds with improved stability, species selectivity, and versatility of synthesis.

FIGURE 1.

Chemical structures of key compounds in this study.

It is important to note that BPL was one of 70 molecular targets investigated by GSK in an antibacterial discovery program using high throughput screening (9). The reported lack of success using this approach highlights the need for a more sophisticated approach to inhibitor discovery and the importance of combining structural biology, enzymology, and biophysical characterization to direct medicinal chemistry. As an important first step we determined the x-ray crystal structures of SaBPL alone and in complex with a chemical analog of 1, biotinol-5′-AMP (2, Fig. 1), that contains a non-hydrolysable phosphodiester linker (25). The challenge is to now incorporate structural biology into the design of potent and selective inhibitors of SaBPL. With this in mind, we report a rational structure-guided design to obtain and characterize potent and selective BPL inhibitors containing a triazole bioisostere of the phosphate group of 1 that possess narrow-spectrum antimicrobial activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Methods

The expression and purification of recombinant SaBPL (10), Escherichia coli BPL (26), and Homo sapiens BPL (8) have been previously described. SaBPL and H. sapiens BPL were obtained with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag. Quantitation of BPL activity was performed as previously described (27, 28) and in the supplemental Experimental Procedures. Methodologies for surface plasmon resonance and circular dichroism are also described in the supplemental Experimental Procedures.

X-ray Crystallography

ApoSaBPL was buffer-exchanged into 50 mm Tris HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, and 5% (v/v) glycerol and concentrated to 5 mg/ml. Each compound was then added to BPL in a 10:1 molar ratio. The complex was crystallized using the hanging drop method at 4 °C in 8–12% (w/v) PEG 8000 in 0.1 m Tris pH 7.5 or 8.0 and 10% (v/v) glycerol as the reservoir. A single crystal was picked using a Hampton silicon loop and streaked through cryoprotectant containing 25% (v/v) glycerol in the reservoir buffer before data collection. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the macromolecular crystallography beamline at the Australian Synchrotron using an ADSC Quantum 210r Detector. 90 images were collected for 1 s each at an oscillation angle of 1° for each frame. Data were integrated using HKL and refined using the CCP4 suite of programs (29). PDB and cif files for the compounds were obtained using the PRODRG web interface. The models were built using cycles of manual modeling using COOT (30) and refinement with REFMAC (29). The quality of the final models was evaluated using MOLPROBITY. Composite omit maps were inspected for each crystal structure and statistics for the data and refinement reported (supplemental Table S1). The crystallography, atomic coordinates, and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, codes 4DQ2 (SaBPL with 2), 3V7C (SaBPL with 7), and 3V7S (SaBPL with 14).

Antibacterial Activity Evaluation

Antimicrobial activity of the compounds was determined by a microdilution broth method as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (Document M07-A8, 2009, Wayne, PA) with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (Trek Diagnostics Systems). Compounds were dissolved using DMSO. Serial 2-fold dilutions of each compound were made using DMSO as the diluent. Trays were inoculated with 5 × 104 colony-forming units of each strain in a volume of 100 μl (final concentration of DMSO was 3.2% (v/v)) and incubated at 35 °C for 16–20 h. Growth of the bacterium was quantitated by measuring the absorbance at 620 nm.

Assay of Cell Culture Cytotoxicity

HepG2 cells were suspended in Dulbecco-modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and then seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates at either 5,000, 10,000, or 20,000 cells per well. After 24 h, cells were treated with varying concentrations of compound, such that the DMSO concentration was consistent at 4% (v/v) in all wells. After treatment for 24 or 48 h, WST-1 cell proliferation reagent (Roche Applied Science) was added to each well and incubated for 0.5 h at 37 °C. The WST-1 assay quantitatively monitors the metabolic activity of cells by measuring the hydrolysis of the WST-1 reagent, the products of which are detectable at absorbance 450 nm.

Synthetic Chemistry Methods

All reagents were from standard commercial sources and of reagent grade or as specified. Solvents were from standard commercial sources. Reactions were monitored by ascending TLC using precoated plates (silica gel 60 F254, 250 μm, Merck), and spots were visualized under ultraviolet light at 254 nm and with either sulfuric acid-vanillin spray, potassium permanganate dip, or Hanessian's stain. Flash chromatography was performed with silica gel (40–63 μm 60 Å, Davisil, Grace, Germany). Melting points were recorded uncorrected on a Reichert Thermovar Kofler microscope. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Gemini (200 MHz) Varian Gemini 2000 (300 MHz) or a Varian Inova 600 MHz. Chemical shifts are given in ppm (δ) relative to the residue signals, which in the case of DMSO-d6 were 2.50 ppm for 1H and 39.55 ppm for 13C and in the case of CDCl3 were 7.26 ppm for 1H and 77.23 ppm for 13C. Structural assignment was confirmed with COSY, rotating-frame overhauser effect spectroscopy (ROESY), HMQC (heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence), and HMBC (heteronuclear multiple bond coherence). High resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded on a Thermo Fisher Scientific LTQ orbitrap FT MS equipment (Δ < 2 ppm) at Adelaide Proteomics, University of Adelaide, and Brucker micro TOF-Q at The Australia Wine Research Institute. Purity for assayed compounds was determined by 1H NMR (>95%). Compounds 2 (25), 3 (31), and 4 (32) were prepared according to literature procedures.

RESULTS

Molecular Basis for Inhibitor Binding

To assist with inhibitor design, the structure of SaBPL in complex with inhibitor biotinol-5′-AMP 2 was determined by x-ray crystallography to 2.5 Å resolution. This revealed that the enzyme contains three domains (Fig. 2A). A helix-turn-helix motif at the N terminus facilitates DNA binding activity. The central and C-terminal domains contain amino acids required for ligand binding and catalysis and adopt SH2- and SH3-like folds, respectively. The overall structures are consistent with the class II enzyme from E. coli (33) (root mean square (r.m.s.d.) of Cα 1.89 Å over 249 amino acids) and with the catalytic region of class I enzymes from Pyrococcus horikoshii (r.m.s.d. 1.89 Å), Aquifex aeolicus (r.m.s.d. 1.8 Å), and M. tuberculosis (r.m.s.d. 1.89 Å) (11, 34–36). The high degree of structural conservation observed in all available BPL structures highlights the challenge in designing selective inhibitors.

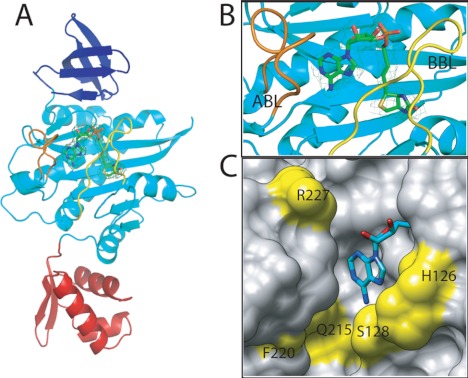

FIGURE 2.

S. aureus BPL in complex with biotinol-5′-AMP. A, SaBPL consists of three structured domains, an N-terminal DNA binding domain (red), a central domain (cyan), and C-terminal domain (dark blue). B, a close-up of the inhibitor binding site shows the relative positions of the ABL (orange) and BBL (yellow). The final 2Fo − 2Fc map is contoured at the 1σ level is shown on inhibitor 2 in ball and stick representation. C, the ATP pocket of SaBPL in complex with 2 is shown in space-filled mode with the adenine portion shown in ball and stick representation. Amino acid residues that line the pocket and that are not conserved between SaBPL and human BPL are highlighted in yellow.

The Cα backbone could be traced from residues Ser-2 to Phe-323, indicating all amino acids were observed in the x-ray diffraction data with the exception of Met 1. Noteworthy were residues Thr-117–Lys-131 and Phe-220–Ala-228 (Fig. 2, A and B). In other BPLs these features, known as the biotin binding loop (BBL) and ATP binding loop (ABL), are not visible in the unliganded form of the enzyme but are observed when ligand is bound. The disordered-to-ordered transition that accompanies ligand binding has been previously reported (33–36). In the complex of SaBPL with 2, the BBL folds against the central β-sheet in the central domain to cover the active site and maintain the reaction intermediate in situ (Fig. 2, A and B). The side chain of Trp-127 in the BBL becomes buried and forms a barrier over which the biotin and adenosine halves of 2 must bend (supplemental Fig. S1), thereby forming distinct biotin and ATP binding pockets. The ribose moiety in 2 assists the inhibitor to bridge the two binding pockets and forms a hydrogen bond through its 2′ hydroxyl group with the side chain of Arg-227 (supplemental Fig. S1). As for other BPLs, the phosphodiester in 2 permits the inhibitor to adopt the same V-shaped geometry observed for 1 binding. The complex with 2 is further stabilized through hydrogen-bonding interactions between the phosphate in the linker with residues in the BBL, namely Arg-122 and Arg-125 (supplemental Fig. S1). The ATP pocket is dominated by the side chain of Trp-127, which is required for a π-π stacking interaction with adenine. The side chains of hydrophobic residues Phe-220, Ile-224, and Ala-228 in the ABL present in the same plane as the purine ring provide a hydrophobic surface for binding. Hydrogen bonding with the side chain of Asn-212 and the backbone nitrogen of Ser-128 within the pocket also stabilize the complex. These key structural features were considered in the design of a chemical mimic of 1 that could function as a selective BPL inhibitor.

An analysis of primary structures reveals that the amino acids involved in binding biotin are highly conserved among all species (supplemental Fig. S2 and Ref. 37). In addition, the x-ray crystal structures show the biotin pocket to be relatively small and hydrophobic, as required to accommodate the ureido and thiophane rings of biotin. This is consistent with reported literature that showed chemical modifications to these heterocycles produced biotin analogues that were unable to be used as substrates by the BPLs from a wide range of species (38). Hence, targeting the biotin site alone is an unattractive approach for inhibitor design. We propose that targeting the ATP binding pocket would provide significant opportunity for introducing selectivity. A comparison of our SaBPL crystal structure with others available in the PDB and also a model of the human BPL active site (7) revealed the amino acid residues in the ATP binding sites to be far more divergent. For example, five of the residues that define the nucleotide binding pocket for SaBPL are not conserved with the sequence of the human BPL. These residues are located immediately around the adenine binding site (Gln-125, Phe-220, and Arg-227) and in the BBL (His-126 and Ser-128). The position of these residues is shown in Fig. 2C (yellow) relative to the adenosine portion of 2 bound in the SaBPL structure.

Biotin Binding Induces Nucleotide Binding Pocket

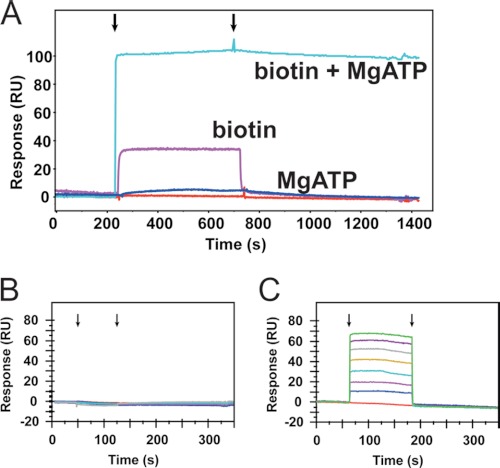

An understanding of the ligand binding mechanism provided important information for inhibitor design. Biophysical analysis of the class II BPL from E. coli has shown that the enzyme possesses an ordered binding mechanism during catalysis with biotin binding first, triggering the disorder-to-order transition that forms the nucleotide binding pocket (33, 39). This ordered binding mechanism was confirmed for SaBPL using surface plasmon resonance. The addition of MgATP to SaBPL that was covalently attached to the matrix did not result in binding (Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast, biotin binds in a concentration-dependent manner with fast association and dissociation kinetics (Fig. 3A). Importantly, when biotin and MgATP were co-administered, a larger magnitude response was observed with the generation of a product that remained on the surface of the sensorchip (Fig. 3A). This is consistent with the immobilized enzyme retaining biotinyl-5′-AMP synthetase activity and the formation of a stable holoenzyme complex. The addition of protein substrate in the running buffer induced a decrease in response of the surface plasmon, as would be expected when SaBPL discharges the reaction intermediate 1 during protein biotinylation (data not shown). This finding agrees with studies on E. coli BPL that demonstrated the holoenzyme complex is stable with a half-life of 30 min (40, 41). This result has a significant impact on inhibitor design. To target the ATP pocket, a successful inhibitor must induce the conformational changes required to form this pocket. We thus chose to incorporate a biotinyl moiety into our inhibitor design. In support of this, surface plasmon resonance analysis showed that MgATP could bind to SaBPL but only after the formation of an enzyme complex with biotin analog 3 (Fig. 3, B and C). It is important that an inhibitor competes with biotin binding because once the ligand occupies the enzyme, the saturating concentration of ATP in the bacterial cell (∼3 mm, versus the Km of SaBPL for ATP at 180 μm; see supplemental Table S2) will drive the formation of intermediate 1 and subsequent biotinylation of the protein substrates.

FIGURE 3.

Binding at the ATP-site is biotin-dependent. The mechanism of ligand binding was monitored using surface plasmon resonance with immobilized SaBPL. A, overlaid are the surface plasmon resonance traces that resulted from the inclusion of either biotin (pink) or MgATP (dark blue) in the running buffer or both ligands co-injected together (cyan). Arrows indicate the start and end of the ligand injection phase. B and C. ATP binding is dependent upon the formation of a biotin-enzyme complex. The surface plasmon resonance traces are shown when increasing concentrations of MgATP were applied to apoSaBPL (B) or SaBPL (C) in a preformed complex with biotin analog 3.

Triazole Linker as Phosphate Isostere

Currently, there are no reports of selective BPL inhibitors in the literature. Biotinol-5′-AMP (2) (25) and the sulfamate analog 5′-amino-5′-N-(biotinyl)sulfamoyl-5′-deoxyadenosine (11) are close mimics of the reaction intermediate (1) that contain non-hydrolysable linkers. We demonstrated that 2 inhibited SaBPL with a Ki = 0.03 ± 0.01 μm in in vitro BPL enzyme assays. However, it was also a potent inhibitor of the human BPL with a Ki = 0.21 ± 0.03 μm. Alternative bioisosteres were considered as a means to link biotin and adenine components identified in our inhibitor design to access selective inhibitors. The 1,2,3-triazole motif is a versatile heterocycle with a number of desirable attributes that made it a good candidate. It is stable to acid/base hydrolysis and reductive and oxidative conditions, rendering it resistant to metabolic degradation. A 1,2,3-triazole ring has three potential hydrogen bond acceptor sites (nitrogens) and a polarized proton and can also participate in π-π interactions. In addition, a 1,2,3-triazole is readily synthesized by an azide alkyne Huisgen cycloaddition reaction under chemically benign conditions (42, 43). As a result, the 1,2,3-triazole has found some applicability as bioisosteric analogues for phosphomonoesters (44), pyrophosphate (45), phosphodiester linkers (46), and phosphoanhydrides (47).

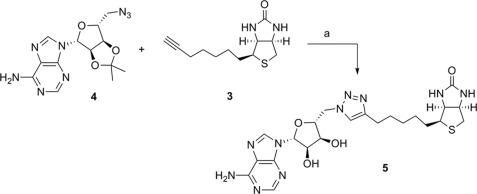

Our first example of this new class of BPL inhibitors was prepared by Huisgen cycloaddition of biotin acetylene (3) with adenosine azide (4) in the presence of copper nanopowder followed by removal of the isopropylidene diol-protecting group, which gave the biotin 1,4-disubstituted triazole-adenosine (5), as shown in Scheme 1. The related triazoles (6, 7, and 8, see Fig. 1) were similarly prepared by reaction of the appropriate azide and acetylene as described in the supplemental Experimental Procedures. In vitro enzyme inhibition studies demonstrated that the triazole (5) was a competitive inhibitor of SaBPL with a Ki of 1.17 ± 0.3 μm. The ribose 2′,3′-diol was deemed not important for activity as the isopropylidene-protected analog of 5 (see 7, Fig. 1) was as equally potent as the unprotected analog (Ki 1.83 ± 0.33 μm, p = 0.2, 5 versus 7). Significantly, it was also observed that shortening or lengthening the valeric acid chain on the biotinyl moiety of 7 by one carbon (see 6 and 8 respectively) abolished inhibitory activity. Similarly, the 1,5-disubstituted triazole-adenosine isomer of 7 (see 9, Fig. 1) was also inactive against SaBPL, presumably because this moiety does not provide the appropriate V-shaped geometry required for active site binding as discussed earlier. This was supported by a crystal structure of 7 bound to SaBPL that revealed the expected mode of binding (discussed later). These data highlight the need for the precise positioning of the isostere in the inhibitor.

SCHEME 1.

Conditions and reagents: a, (i) copper nano-powder, 2:1 MeCN/H2O, 35 °C; (ii) 90% TFA(aq), dichloro-methane (CH2Cl2).

The biotin triazoles 5 and 7 were next tested for inhibitory activity against recombinant E. coli and human BPLs, with both being inactive at the highest concentration achievable without precipitation in the assay medium (typically 200 μm). These are the first compounds that show significant selectivity for SaBPL. The biotin-triazole pharmacophore thus provides a scaffold for further development of selective inhibitors of SaBPL.

Improving Inhibitor Potency and Selectivity

In addition to providing a phosphodiester bioisostere, the triazole linkage provides an ideal opportunity to rationally advance the inhibitor design. A selection of readily available azides, the side chains of which might occupy the ATP pocket, were linked to the acetylene 3 under standard Huisgen cyclo-addition conditions to give a second series of triazole-based inhibitors (see the supplemental Experimental Procedures). Key features of the earlier inhibitors were considered in this stage of the design: (i) the 1,4-disubstituted triazole was retained to allow the inhibitor to adopt the desired V-shape for binding with BPL, (ii) the ribose sugar of 1 was removed as the kinetic data with inhibitors 5 (with unprotected diol) and 7 (protected diol) demonstrated it was not essential for binding, and (iii) the optimum five-carbon linker length between the triazole and biotin groups of 5 and 7 was retained. Two linker lengths between the triazole and potential adenine replacements were investigated, with the choice of analog guided by the hydrophobicity of the ATP binding pocket, defined by the side chains of Phe-220, Ile-224, and Ala-228, and the potential for π interactions with Trp-127. Thus we chose to target triazoles containing aliphatic and aromatic groups (see R group in Table 1) that might be predicted to substitute for adenine and bind in the hydrophobic ATP pocket. A privileged 2-benzoxazolone scaffold (48, 49) was also included in this series (see structures 14 and 16 in Table 1).

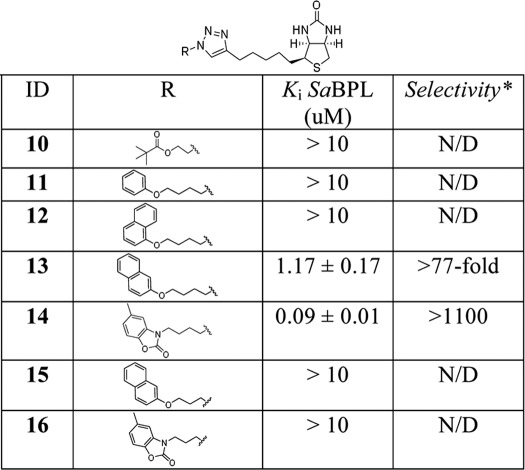

TABLE 1.

Structure Activity Relationship series of biotin triazoles

* Selectivity is calculated by Ki human BPL/Ki SaBPL, where the Ki for human BPL is the maximum concentration of compound possible in assay medium due to solubility restraints (90 μm). ND, not determined.

The triazole with the appended aliphatic tertiary butyl ester (10) was inactive against SaBPL, as were the phenyl and 1-naphthyl analogues 11 and 12, respectively. Interestingly, the analogous 2-napthyl derivative 13 showed encouraging activity with a Ki = 1.17 ± 0.17 μm. The triazole with the appended 2-benzoxazolone (14) proved to be particularly potent with a Ki of 0.09 ± 0.02 μm (Fig. 4A). Of particular significance was the observation that both compounds 15 and 16 were inactive despite containing the favored aryl groups but a linker reduced by one carbon. This suggests that the correct nature and positioning of the aryl group in the ATP pocket is critical for optimal π stacking and hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions (see the discussion below on the x-ray crystal structures of complexes with 7 and 14).

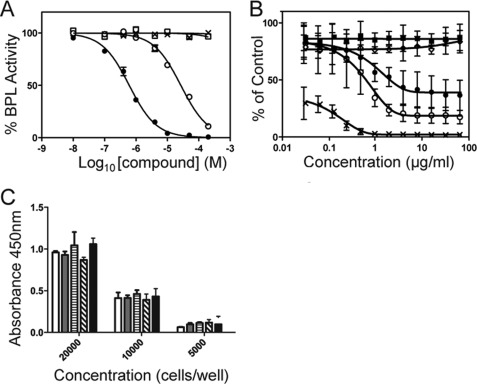

FIGURE 4.

Biological assays. A, differential inhibition is shown. BPL activity was measured in vitro with varying concentrations of 14. The assays were performed using recombinant BPL from S. aureus (●), E. coli (□), and H. sapiens (×). The mutant Arg-125→Asn was also included (○). B, anti-Staphylococcus activity is shown. Inhibition of the growth of S. aureus ATCC 49775 was measured using a microbroth dilution assay with varying concentrations of 2 (○), 13 (◊) and 14 (●). No inhibitor (■) and erythromycin (×) served as negative and positive controls, respectively. C, the cytotoxicity of the biotin triazole series was assessed on HepG2 cells using an assay for metabolic activity. Cells were seeded at either 20,000, 10,000, or 5,000 cells per well and treated for 48 h with media containing 64 μg/ml of compound and 4% (v/v) DMSO. The treatments in this series were the DMSO vehicle control (white bar), 5 (gray bar), 7 (horizontal stripe), 13 (diagonal stripe), and 14 (black bar).

Biotin triazole 14 was confirmed as a competitive inhibitor versus biotin using Lineweaver-Burke analysis. Critically for this study, the biotin triazoles 13 and 14 were inactive against both human and E. coli BPLs in vitro at concentrations limited by solubility. For biotin triazole 14 the selectivity for SaBPL was >1100-fold over the human isozyme (Fig. 4A), making this compound by far the most significant example of a selective BPL inhibitor reported to date.

Anti-microbial Activity of Biotin-triazoles

The anti-microbial activity of selected SaBPL inhibitors was measured against S. aureus ATCC strain 49775 using a microbroth dilution assay. Bacteriostatic activity was observed with the pan inhibitor 2, demonstrating for the first time that the BPL target is indeed drug-receptive in S. aureus in an in vitro setting (minimal inhibitory concentration 8–32 μg/ml). The most potent of the triazole inhibitors (14) also reduced cell growth by 80% when 8 μg/ml was included in the growth medium (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, triazole 13 did not show anti-microbial activity even though it is only 13-fold less potent than 14 in an in vitro enzyme inhibition assay. This suggests that additional factors such as uptake across the bacterial membrane impact on the utility of this class of compounds. Biotin triazoles 13 and 14 were both inactive against E. coli ATCC strain 25922 in the micro-broth dilution assay. This is consistent with the fact that both were inactive against E. coli BPL. Importantly, 5, 7, 13, and 14 did not show any toxicity in a cell culture model using HepG2 cells (Fig. 4C). Cells seeded at three different densities were treated with 64 μg/ml in the growth media for 48 h with no inhibition of cell growth, consistent with the lack of inhibitory activity against human BPL in vitro.

X-ray Structures of Biotin-triazoles Bound to SaBPL

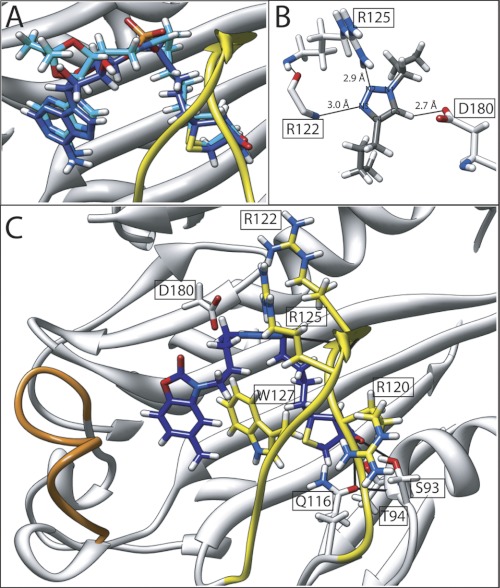

The x-ray crystal structures of SaBPL in complex with this new class of BPL inhibitor (7 and 14) were determined to define their mode of binding (Fig. 5). A comparison of these structures with the enzyme complex of 2 revealed the biotin triazole inhibitors adopted the same V-shaped geometry in the active site as the inhibitor 2. Indeed, a superimposition of the backbone atoms for SaBPL from the holo and 7-bound structures showed an almost perfect overlay highlighting the isosteric nature of the triazole relative to the phosphate moiety (Fig. 5A). Additionally, many of the hydrogen-bonding interactions were retained in all structures. The isopropylidene protecting group on inhibitor 7 caused the displacement of the Arg-227 side chain away from its position noted in our other x-ray structures, thereby disrupting a potential hydrogen bond (supplemental Fig. S3). However, the fact that the protecting group showed no effect on inhibitor potency (see 5 versus 7 above) suggests that the ribose ring in 1 is dispensable, consistent with inhibitor design principles described previously. Importantly, the triazole group assists to stabilize the enzyme: inhibitor complex through hydrogen bonding interactions with residues in the BBL, namely N2 with the guanidinium side chain of Arg-125 and N3 and the backbone amide at Arg-122 (Fig. 5B). The proton at C5 of the triazole ring also formed a hydrogen bond with the carboxylate side chain of Asp-180. In addition, the triazole ring participates in an edge-tilted-T shape interaction with Trp-127 (Fig. 5B). Crystal structures of 7 and 14 in a co-complex with SaBPL all revealed that the inhibitors occupied both biotin and ATP pockets as per our inhibitor design and again with the expected V-shaped geometry essential for binding (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Mode of inhibitor binding. A, the backbone atoms of SaBPL in complex with inhibitor 2 (dark blue) and inhibitor 7 (cyan) were superimposed to reveal the remarkable overlap in the conformations imparted by the triazole bioisostere. B, hydrogen bonding interactions between SaBPL and the trizole ring are shown. C, the crystal structure of biotin triazole 14 (dark blue) bound in the active site of SaBPL. Hydrogen bonding contacts with the amino acids of SaBPL are shown. The BBL is highlighted in yellow, and the ABL is in orange.

The x-ray crystal structure of SaBPL in complex with 7 reveals the adenine ring adopts an analogous binding mechanism to that observed with the holoenzyme complex with inhibitor 2 (discussed earlier). Hence, the requisite properties necessary for binding in the ATP pocket are maintained, namely π-π stacking interaction with Trp-127, hydrophobic interactions with the ABL, and hydrogen-bonding interactions with Asn-212 and Ser-128 located at the bottom of the ATP pocket (supplemental Fig. S4A). Conversely, the benzoxazolone ring of 14 adopts a displaced π interaction with Trp-127 that places the carbamate ring at the top of the ATP pocket (3.6 Å from the Arg-122 side chain; Fig. 5C). The angular placement of the benzoxazolone is accommodated by the grooved hydrophobic region created by Phe-220, Ile-224, and Ala-228 (supplemental Fig. S4B). Unlike the adenine-containing compounds 1, 2, and 7, the benzoxazolone ring in 14 does not appear to hydrogen-bond with the protein (Fig. 5C), suggesting the interaction with the ATP pocket is primarily through hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions. To the best of our knowledge this is the first evidence of a so-called privileged 2-benzoxazolone scaffold binding in an ATP pocket.

Arg-125 Contributes to Selectivity of Biotin-triazoles

To further probe the mechanism of selectivity, we addressed the role of Arg-125 in the binding mechanism by mutagenesis. As the equivalent amino acid residue in human BPL is a non-conservative asparagine, we proposed that Arg-125 in SaBPL was likely to be a key determinant in the selective binding mechanism employed by the biotin triazoles. To test this hypothesis, we generated a mutant SaBPL with an arginine-to asparagine-substitution (SaBPL Arg-125 → Asn) as well as an alanine substitution (SaBPL Arg-125 → Ala). CD analysis demonstrated the amino acid substitutions did not destabilize the SaBPL secondary structure (supplemental Fig. S5). Similarly, kinetic analysis demonstrated that the affinity for biotin was unaltered by the mutation and the Km for MgATP had a modest increase of only 2-fold (supplemental Table S2). Significantly, the largest difference observed between the enzymes was the turnover rate with the kcat reduced by >500-fold by both amino acid substitutions. This implied a key role for this residue and the BBL in catalysis. As expected, the pan inhibitor 2 also functioned as an inhibitor against Arg-125 → Asn (Ki = 0.199 ± 0.028 μm, p < 0.05 versus Wt SaBPL, p < 0.001 versus human BPL). In contrast the inhibitory activity of biotin triazole 5 was abolished. Although 14 retained inhibitory activity against both muteins (Arg-125 → Ala Ki = 4.38 ± 0.39 μm, Arg-125 → Asn Ki = 4.47 ± 0.47 μm), it remained significantly more potent against wild type SaBPL (Wt Ki = 0.09 ± 0.01 μm, p < 0.0001 Wt versus mutein) (Fig. 4A). Together these data support the hypothesis that Arg-125 plays a key role in the selective inhibition by the biotin triazoles.

DISCUSSION

In this study we present the first selective inhibitors of S. aureus biotin protein ligase using an analog of the reaction intermediate, biotinol-5′AMP (2), as the starting point for inhibitor design. This new class of inhibitor contains a 1,2,3-triazole-based bioisostere of the chemically unstable phosphate-based linkages found in the native reaction intermediate 1 and inhibitor 2. We also considered the hypothesis that a close mimic of the reaction intermediate 1 that targets the BPL active site would have a high barrier for developing drug resistance due to spontaneous mutation (6). However, the conserved reaction mechanism employed by all BPLs that utilizes adenylated biotin coupled with the high degree of homology in the primary and tertiary structures suggested that this would be challenging (50). Here we utilized structural biology to assist in the rational design of inhibitors that overcome this problem. An important consideration was the disordered-to-ordered transition that accompanies catalysis. The BBL that is observed in the crystal structures of holo BPLs, but not apo structures, plays a key role to stabilize the BPL-ligand complex. The reaction intermediate is maintained in situ in the active site through interactions with amino acids in this loop, especially with the phosphate-containing linkers in 1 and 2. We argued that an effective mimic of 1 should also interact with amino acids in the BBL. Indeed, replacement of the phosphate linker with a 1,2,3-triazole bioisostere yielded a series of potent and selective inhibitors of SaBPL. The triazole linker provided selective binding via a key amino acid (Arg-125) present in the BBL of SaBPL. This amino acid is not conserved between BPLs, thereby contributing to the selective inhibition. Mutation studies targeting Arg-125 confirmed the mode of binding and demonstrated that this amino acid is important for BPL activity and selectivity. The mutein displayed a reduced enzyme catalytic turnover rate of >500-fold. This reduction of specific enzyme activity should be a significant barrier for the development of drug resistance to the biotin-triazoles by spontaneous mutation, as we initially proposed.

The triazole linkage provides an opportunity to develop BPL inhibitors using well documented reaction conditions that give rise to both the 1,4- and 1,5-disubstituted triazole isomers. BPL provides an attractive template for a fragment-based approach with the biotin and ATP pockets juxtaposed in the crystal structures. Compounds that reside in the two pockets can be joined via a 1,2,3-triazole that constrains the partners in the same V-shaped geometry naturally observed for enzyme bound 1. The biotin-dependent ATP binding mechanism employed by BPLs prevents targeting the ATP site alone. However, by incorporating a biotin moiety into the inhibitor, the ATP pocket can be formed and explored as an avenue toward an optimized inhibitor. There have been reports of large pharma repositioning their nucleotide-analog libraries, assembled for screening eukaryotic protein kinase targets, for antibiotic discovery. Successful examples in the literature include acetyl-CoA carboxylase (51), histidine kinase (52), and d-alanine-d-alanine ligase (53). The availability of high resolution crystal structures of SaBPL is necessary to direct future chemical optimization.

The mechanism of selective inhibition reported in this study provides the first approach to antibiotics based on the selective inhibition of BPL. To date, target-based antibiotic discovery has focused upon metabolic enzymes and pathways that are found exclusively in bacterial pathogens (54, 55). As a result, targets with close equivalents in mammalian hosts have typically been excluded from consideration. We demonstrate an important new approach to antibiotic discovery based on the selective inhibition of a bacterial target (BPL) that has a mammalian homologue. Examples of antibiotics in clinical use that selectively target a bacterial protein include ribosome inhibitors, such as macrolides, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, and linezolid (56). In this example, however, the differences between the bacterial and eukaryotic ribosomal proteins are large and provide adequate opportunities for selective binding of drugs. More challenging for antibiotic drug discovery are the drug targets that more closely resemble their mammalian counterparts, as addressed in this paper. The implication from work presented in this study refocuses discussion on what constitutes a drug-responsive target for antibiotic discovery. Given the clinical demand for new agents to combat drug resistance across the globe, these studies are timely.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jackie Wilce for constructive critique of the manuscript. Diffraction data were collected at the Australian Synchrotron. We also acknowledge the computer resources of the Victorian Partnership for Advanced Computing. We thank Prof. John Cronan (University of Illinois) for the kind gift of biotinol-5′-AMP.

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (applications 565506 and 1011806) and Adelaide Research and Innovation's Commercial Accelerator Scheme.

This article contains supplemental Experimental Procedures, Figs S1–S5, and Tables S1 and S2.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4DQ2, 3V7C, and 3V7S) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- BPL

- biotin protein ligase

- SaBPL

- S. aureus

- BBL

- biotin binding loop

- ABL

- ATP binding loop.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cooper M. A., Shlaes D. (2011) Fix the antibiotics pipeline. Nature 472, 32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boucher H. W., Talbot G. H., Bradley J. S., Edwards J. E., Gilbert D., Rice L. B., Scheld M., Spellberg B., Bartlett J. (2009) Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect Dis. 48, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deleo F. R., Otto M., Kreiswirth B. N., Chambers H. F. (2010) Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 375, 1557–1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Turnidge J. D., Kotsanas D., Munckhof W., Roberts S., Bennett C. M., Nimmo G. R., Coombs G. W., Murray R. J., Howden B., Johnson P. D., Dowling K. (2009) Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. A major cause of mortality in Australia and New Zealand. Med. J. Aust. 191, 368–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. von Itzstein M. (2007) The war against influenza. Discovery and development of sialidase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 967–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colman P. M. (2009) New antivirals and drug resistance. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 95–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pendini N. R., Bailey L. M., Booker G. W., Wilce M. C., Wallace J. C., Polyak S. W. (2008) Microbial biotin protein ligases aid in understanding holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784, 973–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mayende L., Swift R. D., Bailey L. M., Soares da Costa T. P., Wallace J. C., Booker G. W., Polyak S. W. (2012) A novel molecular mechanism to explain biotin-unresponsive holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency. J. Mol. Med. 90, 81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Payne D. J., Gwynn M. N., Holmes D. J., Pompliano D. L. (2007) Drugs for bad bugs. Confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pendini N. R., Polyak S. W., Booker G. W., Wallace J. C., Wilce M. C. (2008) Purification, crystallization, and preliminary crystallographic analysis of biotin protein ligase from Staphylococcus aureus. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 64, 520–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duckworth B. P., Geders T. W., Tiwari D., Boshoff H. I., Sibbald P. A., Barry C. E., 3rd, Schnappinger D., Finzel B. C., Aldrich C. C. (2011) Bisubstrate adenylation inhibitors of biotin protein ligase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem. Biol. 18, 1432–1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parsons J. B., Frank M. W., Subramanian C., Saenkham P., Rock C. O. (2011) Metabolic basis for the differential susceptibility of Gram-positive pathogens to fatty acid synthesis inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 15378–15383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Freiberg C., Pohlmann J., Nell P. G., Endermann R., Schuhmacher J., Newton B., Otteneder M., Lampe T., Häbich D., Ziegelbauer K. (2006) Novel bacterial acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase inhibitors with antibiotic efficacy in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 2707–2712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jitrapakdee S., St Maurice M., Rayment I., Cleland W. W., Wallace J. C., Attwood P. V. (2008) Structure, mechanism, and regulation of pyruvate carboxylase. Biochem. J. 413, 369–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chaudhuri R. R., Allen A. G., Owen P. J., Shalom G., Stone K., Harrison M., Burgis T. A., Lockyer M., Garcia-Lara J., Foster S. J., Pleasance S. J., Peters S. E., Maskell D. J., Charles I. G. (2009) Comprehensive identification of essential Staphylococcus aureus genes using transposon-mediated differential hybridization (TMDH). BMC Genomics 10, 291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Forsyth R. A., Haselbeck R. J., Ohlsen K. L., Yamamoto R. T., Xu H., Trawick J. D., Wall D., Wang L., Brown-Driver V., Froelich J. M., Keder G. C., King P., McCarthy M., Malone C., Misiner B., Robbins D., Tan Z., Zhu Zy Z. Y., Carr G., Mosca D. A., Zamudio C., Foulkes J. G., Zyskind J. W. (2002) A genome-wide strategy for the identification of essential genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 1387–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ji Y., Zhang B., Van S. F., Horn, Warren P., Woodnutt G., Burnham M. K., Rosenberg M. (2001) Identification of critical staphylococcal genes using conditional phenotypes generated by antisense RNA. Science 293, 2266–2269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hurdle J. G., O'Neill A. J., Chopra I. (2005) Prospects for aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitors as new antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 4821–4833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yu X. Y., Hill J. M., Yu G., Wang W., Kluge A. F., Wendler P., Gallant P. (1999) Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of a series of novel thiazoles as inhibitors of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 9, 375–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Forrest A. K., Jarvest R. L., Mensah L. M., O'Hanlon P. J., Pope A. J., Sheppard R. J. (2000) Aminoalkyl adenylate and aminoacyl sulfamate intermediate analogues differ greatly in affinity for their cognate Staphylococcus aureus aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 10, 1871–1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bernier S., Akochy P. M., Lapointe J., Chênevert R. (2005) Synthesis and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitory activity of aspartyl adenylate analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 13, 69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee J., Kang S. U., Kang M. K., Chun M. W., Jo Y. J., Kwak J. H., Kim S. (1999) Methionyl adenylate analogues as inhibitors of methionyl-tRNA synthetase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 9, 1365–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tian Y., Suk D. H., Cai F., Crich D., Mesecar A. D. (2008) Bacillus anthracis o-succinylbenzoyl-CoA synthetase. Reaction kinetics and a novel inhibitor mimicking its reaction intermediate. Biochemistry 47, 12434–12447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patrone J. D., Yao J., Scott N. E., Dotson G. D. (2009) Selective inhibitors of bacterial phosphopantothenoylcysteine synthetase. J. Am Chem. Soc. 131, 16340–16341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brown P. H., Cronan J. E., Grøtli M., Beckett D. (2004) The biotin repressor. Modulation of allostery by corepressor analogs. J. Mol. Biol. 337, 857–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chapman-Smith A., Mulhern T. D., Whelan F., Cronan J. E., Jr., Wallace J. C. (2001) The C-terminal domain of biotin protein ligase from E. coli is required for catalytic activity. Protein Sci. 10, 2608–2617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Polyak S. W., Chapman-Smith A., Brautigan P. J., Wallace J. C. (1999) Biotin protein ligase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The N-terminal domain is required for complete activity. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32847–32854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Polyak S. W., Chapman-Smith A., Mulhern T. D., Cronan J. E., Jr., Wallace J. C. (2001) Mutational analysis of protein substrate presentation in the post-translational attachment of biotin to biotin domains. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3037–3045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite. Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot. Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Corona C., Bryant B. K., Arterburn J. B. (2006) Synthesis of a biotin-derived alkyne for pd-catalyzed coupling reactions. Org Lett. 8, 1883–1886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Comstock L. R., Rajski S. R. (2002) Expeditious synthesis of aziridine-based cofactor mimics. Tetrahedron 58, 6019–6026 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wood Z. A., Weaver L. H., Brown P. H., Beckett D., Matthews B. W. (2006) Co-repressor induced order and biotin repressor dimerization. A case for divergent followed by convergent evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 357, 509–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bagautdinov B., Kuroishi C., Sugahara M., Kunishima N. (2005) Crystal structures of biotin protein ligase from Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3 and its complexes. Structural basis of biotin activation. J. Mol. Biol. 353, 322–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tron C. M., McNae I. W., Nutley M., Clarke D. J., Cooper A., Walkinshaw M. D., Baxter R. L., Campopiano D. J. (2009) Structural and functional studies of the biotin protein ligase from Aquifex aeolicus reveal a critical role for a conserved residue in target specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 387, 129–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gupta V., Gupta R. K., Khare G., Salunke D. M., Surolia A., Tyagi A. K. (2010) Structural ordering of disordered ligand binding loops of biotin protein ligase into active conformations as a consequence of dehydration. PLoS One 5, e9222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chapman-Smith A., Cronan J. E. (1999) Molecular biology of biotin attachment to proteins. J. Nutr. 129, 477S-484S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Slavoff S. A., Chen I., Choi Y. A., Ting A. Y. (2008) Expanding the substrate tolerance of biotin ligase through exploration of enzymes from diverse species. J. Am Chem. Soc. 130, 1160–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xu Y., Nenortas E., Beckett D. (1995) Evidence for distinct ligand-bound conformational states of the multifunctional Escherichia coli repressor of biotin biosynthesis. Biochemistry 34, 16624–16631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Naganathan S., Beckett D. (2007) Nucleation of an allosteric response via ligand-induced loop folding. J. Mol. Biol. 373, 96–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Streaker E. D., Beckett D. (2003) Coupling of protein assembly and DNA binding. Biotin repressor dimerization precedes biotin operator binding. J. Mol. Biol. 325, 937–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Meldal M., Tornøe C. W. (2008) Copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition. Chem. Rev. 108, 2952–3015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rostovtsev V. V., Green L. G., Fokin V. V., Sharpless K. B. (2002) A stepwise Huisgen cycloaddition process. Copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective “ligation” of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 41, 2596–2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Byun Y., Vogel S. R., Phipps A. J., Carnrot C., Eriksson S., Tiwari R., Tjarks W. (2008) Synthesis and biological evaluation of inhibitors of thymidine monophosphate kinase from Bacillus anthracis. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 27, 244–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen L., Wilson D. J., Xu Y., Aldrich C. C., Felczak K., Sham Y. Y., Pankiewicz K. W. (2010) Triazole-linked inhibitors of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase from human and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Med. Chem. 53, 4768–4778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. El-Sagheer A. H., Brown T. (2010) Click chemistry with DNA. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 1388–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Somu R. V., Boshoff H., Qiao C., Bennett E. M., Barry C. E., 3rd, Aldrich C. C. (2006) Rationally designed nucleoside antibiotics that inhibit siderophore biosynthesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Med. Chem. 49, 31–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Costantino L., Barlocco D. (2006) Privileged structures as leads in medicinal chemistry. Curr. Med. Chem. 13, 65–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Poupaert J., Carato P., Colacino E., Yous S. (2005) 2(3H)-benzoxazolone and bioisosters as “privileged scaffold” in the design of pharmacological probes. Curr. Med. Chem. 12, 877–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Campbell J. W., Cronan J. E., Jr. (2001) Bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis. Targets for antibacterial drug discovery. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55, 305–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Polyak S. W., Abell A. D., Wilce M. C., Zhang L., Booker G. W. (2012) Structure, function, and selective inhibition of bacterial acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 93, 983–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schreiber M., Res I., Matter A. (2009) Protein kinases as antibacterial targets. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Triola G., Wetzel S., Ellinger B., Koch M. A., Hübel K., Rauh D., Waldmann H. (2009) ATP competitive inhibitors of d-alanine-d-alanine ligase based on protein kinase inhibitor scaffolds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 1079–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Frearson J. A., Wyatt P. G., Gilbert I. H., Fairlamb A. H. (2007) Target assessment for antiparasitic drug discovery. Trends Parasitol. 23, 589–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Raman K., Yeturu K., Chandra N. (2008) targetTB: a target identification pipeline for Mycobacterium tuberculosis through an interactome, reactome, and genome-scale structural analysis. BMC Syst. Biol. 2, 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yonath A. (2005) Antibiotics targeting ribosomes. Resistance, selectivity, synergism, and cellular regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 649–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.