Background: Modes of neurotoxic action after Mn overexposure are not fully understood.

Results: The blood-CSF barrier showed higher Mn sensitivity and active Mn transport properties.

Conclusion: The blood-CSF barrier might be the major route for Mn into the brain.

Significance: Deeper insight in the impact of Mn on and its transfer across brain barrier systems might help to prevent irreversible neurological damage.

Keywords: Brain, Cell Culture, Manganese, Neurological Diseases, Toxicology, Blood-CSF Barrier, Blood-Brain Barrier, Manganese, Neurotoxicity

Abstract

Manganese occupational and dietary overexposure has been shown to result in specific clinical central nervous system syndromes, which are similar to those observed in Parkinson disease. To date, modes of neurotoxic action of Mn are still to be elucidated but are thought to be strongly related to Mn accumulation in brain and oxidative stress. However, the pathway and the exact process of Mn uptake in the brain are yet not fully understood. Here, two well characterized primary porcine in vitro models of the blood-brain and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) barrier were applied to assess the transfer of Mn in the brain while monitoring its effect on the barrier properties. Thus, for the first time effects of MnCl2 on the integrity of these two barriers as well as Mn transfer across the respective barriers are compared in one study. The data reveal a stronger Mn sensitivity of the in vitro blood-CSF barrier compared with the blood-brain barrier. Very interestingly, the negative effects of Mn on the structural and functional properties of the highly Mn-sensitive blood-CSF barrier were partly reversible after incubation with calcium. In summary, both the observed stronger Mn sensitivity of the in vitro blood-CSF barrier and the observed site-directed, most probably active, Mn transport toward the brain facing compartment, reveal that, in contrast to the general assumption in literature, after oral Mn intake the blood-CSF barrier might be the major route for Mn into the brain.

Introduction

Manganese (Mn) is an essential trace element required for normal growth development and cellular homeostasis (1). In the brain, Mn is of central importance as co-factor for a wide variety of enzymes, including arginase, pyruvate carboxylase, the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase, as well as enzymes involved in neurotransmitter synthesis and metabolism. Very interestingly, an imbalance in Mn homeostasis caused by either Mn deficiency or overload is well known to result in severe CNS dysfunction. However, whereas Mn deficiency is extremely rare in humans, toxicity is more prevalent. Excessive brain Mn promotes potent neurotoxic effects with symptoms including tiredness, behavioral changes, and delayed neurological disturbances characterized by dystonia or kinesia, resembling many clinical features of parkinsonism but also distinct dissimilarities (2); the neurological phenotype is known as manganism (3). A primary source for Mn intoxication is the occupational exposure in miners, welders, or workers in dry-cell battery factories. In addition, individuals receiving total parenteral nutrition, the contrast agent MnDPDP (also called manganese(II) N,N′-dipyridoxylethylenediamine-N,N′-diacetate-5,5′-bis(phosphate); mangafodipirtri-sodium; TESLASCANTM), or drinking water with high levels of Mn are at higher risk for Mn intoxication; subtle preclinical neurological effects such as changes in cognitive abilities, short term memory, and motor control have been documented (4–7).

To date, the underlying mechanisms of Mn-induced neurotoxicity are still to be elucidated. Several modes of action are discussed, among others oxidative stress, subsequent DNA damage, and mitochondrial dysfunction in specific brain regions. Manganism is associated with elevated Mn levels in certain brain areas, namely cautate-putamen, globus pallidus, substantia nigra, and subthalamic nucleus (8, 9).

Brain manganese homeostasis is largely regulated by the blood-brain barrier (BBB)2 and blood-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) barrier. The BBB separates blood from brain interstitial fluid and consists basically of capillary endothelial cells connected by narrow tight junctions which prevent paracellular flux processes. Moreover, recently it has become evident that the cells of the neurovascular unit, namely astrocytes, pericytes, and neuronal cells are further essential for the induction and maintenance of the BBB properties (10). The second regulating system, the blood-CSF barrier, is built up by the epithelial cells of the choroid plexus (CP) and separates blood from the CSF. This epithelial barrier, which is sealed with tight junctions between the epithelial cells at the CSF-facing surface (apical surface) becomes indispensable because the endothelium of the CP is leaky and highly permeable. Despite the CSF secretion, as the best recognized feature of the CP, further CP functions include general brain homeostasis as well as defense of the brain against harmful substances (11).

Although Mn can cross the BBB and the blood-CSF barrier through several carriers in different oxidation states, the exact identity of the transporter(s) responsible as well as the process itself are still strongly debated. How Mn crosses the BBB has been a subject of many studies, and it appears that several pathways are operative, including facilitated diffusion (12) and active transport. Mn is discussed to be transported among others via the divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), the transferrin receptor (TfR), the divalent metal/bicarbonate ion symporters ZIP8 and ZIP14, various calcium channels, the solute carrier-39 (SLC39) family of zinc transporters, park9/ATP13A2, the magnesium transporter hip14, the transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7) channels/transporters, homomeric purinreceptors (P2X and P2Y), and the citrate transporter (3, 13–16).

In contrast, transfer of Mn across the blood-CSF barrier has been less studied. Proposed transporters include TfR, DMT1, metal transporter protein-1 (MTP1), Ca channels or zinc-transporter (ZnT1, ZnT3, ZnT4, and ZnT6) (summarized in Ref. 16).

Regarding the question of which Mn species enter the brain, Mn(II), Mn(II/III)citrate, and Mn(III)transferrin are likely to be most relevant. Thereby, interestingly the Mn valence status might account for the transport properties at the respective barrier. Whereas Mn(III) enters the brain via TfR-mediated mechanisms, Mn(II) is most likely readily taken up as free ion species or as a nonspecific protein-bound species (17, 18).

In this work, two well characterized cell culture models of the BBB and the blood-CSF barrier were used to assess the transfer of Mn in the brain while monitoring its effect on the barrier properties. These two porcine-based in vitro models allow for the first time a direct comparison of the effects of Mn on and the respective Mn transfer across the BBB and the blood-CSF barrier. Thereby, also the different impacts on the barriers are illustrated when MnCl2 is exposed from blood- or brain-facing sides. Furthermore, this paper indicates that the negative effects of Mn on the barrier properties of the highly Mn-sensitive blood-CSF barrier are partly reversible after treatment with Ca-enriched serum-free medium.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of MnCl2 and CaCl2 Stock Solution

MnCl2 (>99.995% purity) and CaCl2 (> 99% purity) (Sigma-Aldrich) stock solution were prepared in sterile bidistilled water. To prevent oxidation, stock solutions were prepared shortly before each experiment.

Isolation of Primary Porcine Brain Capillary Endothelial and Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells

Primary porcine brain capillary endothelial cells (PBCECs) were isolated, cultivated and cryopreserved as previously described (19). Primary porcine choroid plexus cells (PCPECs) were prepared as described before (20) with slight modifications. Briefly, CP tissue from freshly slaughtered pigs was incubated with 0.2% trypsin at 4 °C for 45 min and warmed to 37 °C for 30 min. The release of the epithelial cells from the basal lamina was stopped by adding newborn bovine serum (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany). The cells were centrifuged at 20 × g and resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/Ham's F-12 (1:1) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 4 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all Biochrom), 5 μg/ml insulin, and 20 mm cytosine arabinoside (both Sigma-Aldrich). The nucleoside analog cytosine arabinoside suppressed the growth of fibroblastic cells (21).

BBB Cell Culture Model

PBCECs were gently thawed and seeded (250,000/cm2) on rat tail (22) collagen-coated (0.54 mg/ml) Transwell® filter inserts with microporous polycarbonate membranes (Corning, Wiesbaden, Germany, 1.12-cm2 growth area, 0.4-μm pore size) on day in vitro (DIV) 2 in plating medium (Medium 199 Earle supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum (NCS), 0.7 mm l-glutamine, 100 μg/ml gentamycin, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all Biochrom)) in the apical compartment at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 100% humidity. After PBCECs reached confluence (DIV4), the plating medium was replaced by serum-free culture medium (SFM-PBCEC) (DMEM/Ham's F-12 (1:1) containing 4.1 mm l-glutamine, 100 μg/ml gentamycin, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all Biochrom)) and 550 nm hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich) to induce differentiation. Permeability ([14C]sucrose, MnCl2) and barrier integrity studies were started on day DIV6.

BBB Co-culture Model

A co-culture model of PBCECs and CCF-STTG1 was used as described previously (23). CCF-STTG1 (CCL-1718TM, American Type Culture Collection) cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Biochrom) containing 10% FBS (PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria), 1.4 mm l-glutamine (Biochrom), 100 units of penicillin/ml and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml (PAA Laboratories) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 100% humidity. For the co-culture system, CCF-STTG1 cells were trypsinized and seeded (100,000 cells/cm2) on the lower side of the microporous Transwell® filter insert (1.12-cm2 growth area, 3-μm pore size) to simulate a direct co-culture. Six hours later, the inserts were turned around and placed into the well, and PBCECs were seeded on the upper side of the insert, which was coated with rat tail collagen, and the co-culture system was subsequently cultured as described above.

Blood-CSF Barrier Cell Culture Model

PCPECs were seeded on MatrigelTM-coated (Sigma-Aldrich) microporous Transwell® filter inserts in the apical compartment using a seeding density of 30 cm2/g wet weight of CP tissue (DIV1). Thereafter, medium was changed every second day. On day DIV8, cells reached confluence, and the medium was replaced by serum-free medium (SFM-PCPEC) (DMEM/Ham's F 12 (1:1) supplemented with 4 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 5 μg/ml insulin) to allow full cell differentiation. The cells were further supplemented with SFM on DIV11, and barrier integrity and transport studies were started on day DIV13, when the cells were fully differentiated and built up their respective functions (21, 24). PCPECs started to actively pump medium from the basolateral into the apical chamber, a process that is comparable with the secretion of cerebrospinal fluid in vivo, and transported phenol red to the basolateral chamber. Additionally, the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEERP) increased.

TEER and Capacitance Measurements

The transendothelial electrical resistance (TEERN) and the TEERP were used as parameters for integrity of the respective barriers, measured by the cellZscope® (nanoAnalytics, Münster, Germany) device. The module used was suitable for 24 Transwell® filter system, grown with PBCEC or PCPEC monolayer. The determined capacitance is directly proportional to the plasma membrane surface area. Changes in the basolateral area and changes in protein content and distribution may also contribute to capacitance changes. Only wells with TEERN values >600 ohms × cm2 and capacitance values between 0.45 and 0.6 microfarad/cm2 on day DIV6 indicate a confluent PBCEC monolayer with good barrier properties and were used for the respective experiments. On day DIV13, wells with PCPEC monolayer in which the TEERP values dropped below 600 ohms*cm2 and/or capacitance values dropped below 3.3 microfarads/cm2 were excluded from the respective experiment.

[14C]Sucrose Permeability

Another technique to analyze barrier integrity is the determination of the permeability for radiolabeled [14C]sucrose through the endothelial or epithelial cell layer. Because sucrose is not taken up by endothelial and epithelial cells either by active or facilitated transport, the permeability for sucrose solely depends on the paracellular barrier tightness. At defined time points, as indicated in the respective experiments, radiolabeled [14C]sucrose (Amersham Biosciences) was added to the apical side of the Transwell® filter. By measuring the time-dependent amount of [14C]sucrose that passes to the basolateral side, the permeability was calculated as described previously (22).

Manganese-induced Effects on and Transfer over Barrier Models

To study the impact of Mn on the barrier integrity as well as Mn transfer across the accomplished in vitro barriers, the respective in vitro models were exposed to MnCl2 either on the apical or on the basolateral side or on both sides simultaneously. MnCl2 was applied by replacing 10% of the apical and/or basolateral medium by a freshly prepared MnCl2 solution to finally reach concentrations of 1–500 μm MnCl2 as described in the respective experiments. During the following 72 h of incubation, aliquots were sampled from the apical and basolateral compartments for the flow injection inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry with quadrupole mass analyzer (FIA-ICP-QMS) measurements while monitoring online the respective TEERN/P and capacitance values. Finally, Mn transfer from one compartment to the other was expressed in percentage (in relation to the applied concentration), as concentration (in micromolar) in each of the compartments as well as in case a time-dependent linear correlation as permeability coefficients in centimeters/second (25). Regarding blood-CSF barrier, function of the barrier was additionally assessed by determination of the absorbance (558 nm, NanDrop 1000, PEQLAB Biotechnologie GMBH, Erlangen, Germany) of phenol red in the respective compartments.

In a further, preliminary experiment the DMT1 inhibitor NSC306711 was used to assess the role of DMT1 in the Mn transfer across the blood-CSF barrier. Therefore, the inhibitor stock solutions were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide, and the basolateral compartments of the blood-CSF in vitro barrier model were incubated with 5, 10, 50, and 100 μm NSC306711 (with a final dimethyl sulfoxide concentration ≤1%) immediately prior to the basolateral incubation with MnCl2 (10, 25 μm). Additionally, basolateral incubation with 1% dimethyl sulfoxide was carried out as vehicle control.

The role of the Na+,K+-ATPase in Mn transfer was examined incubating 200 nm selective Na+,K+-ATPase inhibitor ouabain in the basolateral compartment of the blood-CSF in vitro barrier model immediately prior to the basolateral or apical incubation with 10 μm MnCl2.

To study the impact of Ca-enriched media on Mn-induced disturbance of blood-CSF barrier properties, Transwell® filters with PCPEC monolayers were preincubated with 200 μm MnCl2 at the basolateral compartment for 24 h. Thereafter, the respective basolateral media were kept for further 72 h or replaced by either fresh SFM or by fresh SFM enriched with 250 or 500 μm CaCl2 and postincubated for 72 h.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry studies were performed with PCPEC monolayers grown on the Transwell® filters as described previously (26, 27). 1 μg/ml mouse anti-occludin (Zytomed, Berlin, Germany) and 5 μg/ml mouse anti-Na+,K+-ATPase (Upstate Biotech) were applied at 37 °C in a 0.5% BSA (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) solution for 30 and 90 min, respectively.

The secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-mouse (1 μg/ml) (Invitrogen) was also diluted in 0.5% BSA and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Additionally, cell nuclei were stained with 10 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 (bisbenzimide; Sigma-Aldrich) for 0.5 min. Filters with immunostained cells were cut out from the inserts and mounted in Aqua Poly/Mount (Polysciences). Pictures were taken with the fluorescence microscope Axio ImagerM2 (Zeiss) and evaluated with Axiovision 4.5 software (Zeiss).

Cytotoxicity Testing of MnCl2

Cytotoxic effects of MnCl2 on PBCECs and PCPECs were evaluated using the neutral red uptake assay. This assay is based on the ability of viable cells to incorporate and bind the supravital dye neutral red in the lysosomes (28). PBCECs and PCPECs were cultured in 96-well culture plates, which in case of PBCECs were coated with rat tail collagen. Thereby, all culture conditions including media and cell density were absolutely analogous to the below mentioned cultivation of the respective cells on Transwell® filters as well as to the cellular bioavailability studies. Incubation of PBCECs and PCPECs with MnCl2 was performed on DIV6 and DIV13, respectively. After 24- or 72-h incubation, the medium was replaced by neutral red (3-amino-7-dimethylamino-2-methylphenazine hydrochloride) containing medium (70 mg/liter neutral red (Sigma-Aldrich) in SFM used for the respective cells). After dye loading (37 °C, 3 h), cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% formaldehyde (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). The incorporated dye was solubilized in 100 μl of acidified ethanol solution (50% ethanol, 1% acetic acid in PBS), and finally the absorbance in each well was measured by a plate reader (FLUOstar Optima, BMG Labtechnologies, Jena, Germany) at 540 nm.

Manganese Quantification in Cells and Media

Cellular Mn content was determined after ashing of cells by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Due to the low number of cells used and the low Mn concentrations applied in the barrier studies, we were not able to quantify the total Mn content in cells grown on Transwell® filters, but had to use cells, which were grown in culture flasks. Briefly, after 48-h incubation with MnCl2, PBCECs grown on rat tail collagen-coated culture flasks (25 cm2) or PCPECs grown on culture flasks (25 cm2) were washed twice with PBS (37 °C) and incubated 15 min on ice with 300 μl of radioimmuneprecipitation assay buffer (0.01 m Tris (pH 7.6), 0.15 m NaCl, 0.001 m EDTA, 0.001 m PMSF, 1% sodium desoxycholate, 1 mg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml, pepstatin, 0.1% SDS (all Sigma-Aldrich)). Cells were scraped off and sonicated on ice, and the cell suspension was centrifuged at 15,000 × g (4 °C) for 20 min; in an aliquot of the supernatant, the cellular protein level was quantified by the Bradford assay. Subsequently, the cell suspension was mixed again, evaporated, and incubated with the ashing mixture (65% HNO3/30% H2O2 (1/1) (both Merck)) at 95 °C for at least 12 h. After dilution of the ash with bidistilled water, the Mn concentration was determined by FIA-ICP-QMS. This method has been established previously by our group (29) and was applied in the present work to quantify Mn in cells as well as media sampled from the barrier studies. Briefly, the respective samples were incubated with rhodium (final concentration 10 μg/liter) as internal standard, to compensate drift effects and variations of injected volumes, and further diluted 10-fold with bidistilled water before injection. The FIA approach consisted of a liquid chromatography (LC) system without a column mounted, which was coupled with an ICP-QMS. The LC system combined a quaternary low pressure gradient LC pump (AccelaPump1250TM) and a corresponding autosampler (AccelaAutosamplerTM) whose 6-port stainless steel injection valve was connected to the nebulizer of the ICP-QMS (iCAP QcTM) via a polyether ether ketone capillary (inner diameter, 0.13 mm). All instruments were manufactured by Thermo Scientific. The parameters for the Mn measurements with FIA-ICP-QMS are provided in Table 1. The calculated lowest detection limits for Mn in the respective SFM of the applied barrier models were 2.7 and 6.8 μg/liter, respectively.

TABLE 1.

ICP-QMS parameters used for FIA measurements

| Power | 1550 W |

| Cool gas flow | 14 liters/min |

| Auxiliary gas flow | 0.8 L/min |

| Nebulizer gas flow | ≈1 liter/min |

| Nebulizer type | μFlow PFA-ST (ESI, Omaha, NE) |

| Injector inner diameter | 1.8 mm |

| Spray chamber type | Cyclone @ 2.7 °C |

| Mode | CCTED |

| Cell gas | 7% H2 in He (purity > 99.999%) |

| Cell gas flow | ≈5 ml/min |

| Δbias | 3 V |

| Dwell time | 50 ms @ 1 channel |

RESULTS

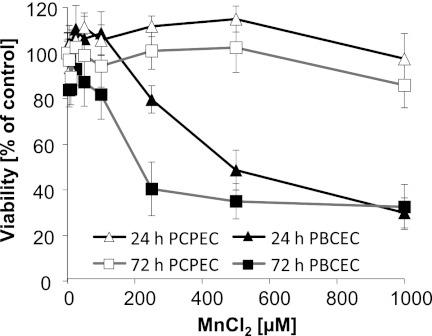

Cytotoxicity Testing

In PCPECs, Mn showed no cytotoxicity as measured by the neutral red uptake assay after 24- and 72-h incubation with up to 1000 μm MnCl2 (Fig. 1). In contrast, in PBCECs cellular viability declined in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. The online measurement of the electrical capacitance further confirmed cytotoxicity of MnCl2 in PBCECs by a concentration-dependent increase (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Cytotoxicity of MnCl2 in confluent PBCECs and PCPECs after 24- or 72-h incubation. Cytotoxicity was determined by a decrease in the cell viability as determined by the neutral red uptake assay. The data represent mean values of at least three independent determinations with six replicates each ± S.D. (error bars).

Manganese Bioavailability

The applied culture media contained 0.03 μm ± 0.01 μm Mn, which is comparable with the reported normal Mn contents in human serum (30). Total Mn concentrations in nonexposed cells were comparable in both cell types, whereas after 48-h MnCl2 incubation, cellular total Mn concentration was about 3-fold lower in PBCECs compared with PCPECs (Table 2). Thus, very interestingly, even though showing lower cellular Mn bioavailability, PBCECs are more sensitive toward Mn cytotoxicity compared with PCPECs.

TABLE 2.

Cellular bioavailability of MnCl2 in PBCECs and PCPECs after 48-h incubation

Data represent mean values of at least two independent determinations each with two replicates ± S.D.

| Incubated MnCl2 | Cellular Mn in PBCECs | Cellular Mn in PCPECs |

|---|---|---|

| μm | μg Mn/mg protein | μg Mn/mg protein |

| 0 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| 50 | 1.14 ± 0.18 | 3.33 ± 0.05 |

| 200 | 2.90 ± 0.76 | 7.63 ± 1.76 |

MnCl2 and BBB

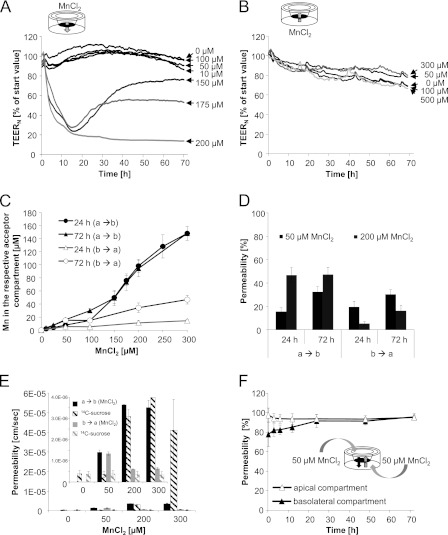

In the first set of experiments, a well characterized cell culture model of the BBB consisting of PBCECs (19, 22) was incubated with increasing concentrations of MnCl2. The PBCECs were grown on Transwell® filter inserts, thereby building up a two-chamber system, which mimics the in vivo CNS situation as closely as possible. The apical compartment refers to the blood side in vivo, and the basolateral side refers to the brain side. The impact of MnCl2 on the barrier integrity was quantified monitoring the TEERN values during the entire 72 h of Mn incubation. Incubating MnCl2 on the apical side, impedance analysis (Fig. 2A) indicated no measurable effect on barrier integrity up to an incubation concentration of 100 μm MnCl2. MnCl2 concentrations of 150 and 175 μm strongly decreased TEERN values within the first 12 h of incubation, but allowed a reconstitution of the barrier integrity in the following hours. In contrast, 200 μm MnCl2 caused an irreversible decrease of the TEERN, indicating an irreversible disruption of the BBB. To verify the results of the TEERN studies, barrier integrity was additionally determined by [14C]sucrose permeability studies. In case of an apical 72-h incubation with 200 or 300 μm MnCl2, the permeation of [14C]sucrose was about 8–100-fold increased compared with control cells (Fig. 2E), indicating strong barrier leakage and disruption. In case of an incubation on the basolateral side, the tightness of the PBCEC monolayer was not impaired by up to 500 μm MnCl2 (Fig. 2B); similarly permeability for [14C]sucrose was not affected (Fig. 2E).

FIGURE 2.

Mn and in vitro BBB. A and B, impact of MnCl2 on the barrier integrity as measured by TEERN values after application of MnCl2 either on the apical (influx studies) (A) or the basolateral compartment (efflux studies) (B). Data, expressed as percentage of start value, represent mean values of at least three independent determinations with three replicates each with S.D. < ±10%. Mean TEERN and capacitance values of control cells were 1016 ± 124 ohms*cm2 and 5.19*10−7 ± 2.55*10−8 microfarads/cm2, respectively. C and D, concentration-dependent Mn transfer to the respective acceptor (not incubated) compartment (C), percentage, normalized to the incubation concentration, Mn transfer (D) after apical or basolateral MnCl2 incubation. E, Mn permeability coefficients and respective permeability coefficients of the permeability marker [14C]sucrose after 72 h MnCl2 apical or basolateral incubation. F, Mn permeability after concurrent MnCl2 incubation of both compartments. C–F, mean values of least three independent determinations with three replicates ± S.D. (error bars); a → b, apical-to-basolateral transfer; b → a, basolateral-to-apical transfer.

For better understanding, Mn barrier transfer results are shown in the respective figures expressed in terms of Mn concentrations in the acceptor compartment (Fig. 2C), as percentage permeability in relation to the applied concentration (Fig. 2D) and as permeability coefficient (Fig. 2E). In case of adding ≤100 μm MnCl2 to the apical compartment, after 24–72 h, Mn concentrations increased in a linear-dependent manner in the basolateral compartment (Fig. 2C). Fig. 2D shows the corresponding crossover of approximately 15% within 24 h and approximately 30% within 72 h, which relates to a permeability coefficient of 1.40*10−6 ± 1.07*10−7 cm/s (Fig. 2E). Due to the leakage of the barrier after incubation with MnCl2 concentrations >100 μm on the apical side (Fig. 2A), a Mn concentration equation between the compartments (Fig. 2D) and thus increased permeability coefficients of up to 3.52*10−6 ± 3.45*10−7 cm/s (300 μm MnCl2) (Fig. 2E) were achieved.

Because in literature very little is known about Mn movement out of the brain into the blood MnCl2 was added to the basolateral side in a second approach. Our data clearly show that up to MnCl2 concentrations of 50 μm, Mn basolateral-to-apical transfer was indistinguishable from the apical-to-basolateral transfer. This indicates that after incubation on the basolateral or the apical side, Mn crossed the barrier in both directions (apical-to-basolateral and basolateral-to-apical transfer) to a comparable extent. In case of basolateral incubation with concentrations >50 μm MnCl2, respective percentage Mn permeabilities (Fig. 2D) and permeability coefficients (Fig. 2E) were strongly reduced.

In a third approach, MnCl2 was incubated in equal concentrations both to the apical and the basolateral medium. No accumulation was visible in one of the compartments within 72 h of incubation with 50 μm MnCl2, pointing to a passive Mn transfer process (Fig. 2F). The TEERN analyses showed similar results compared with a MnCl2 incubation on the apical side and thereby also ruled out that the observed effects on the TEERN values in general were caused by an ionic effect of Mn2+.

In addition to the monoculture BBB experiments, a direct co-culture approach (23) based on the BBB architecture in vivo was used, in which brain capillaries are entirely covered by astrocytic feed. After apical MnCl2 incubation, neither the TEERN analyses nor the transfer experiments showed significant different results compared with the monoculture studies (data not shown).

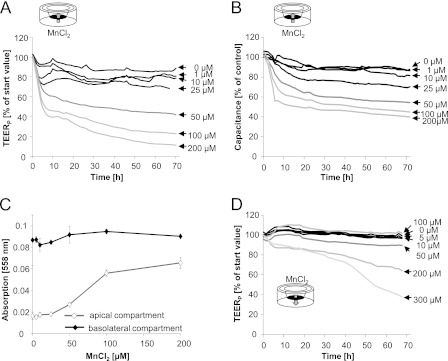

MnCl2 and Blood-CSF Barrier

The next set of experiments focused on the second cellular interface, which regulates the exchange between the blood and CNS, the blood-CSF barrier. The applied, well established in vitro cell culture model of the blood-CSF barrier is built up by PCPECs (20), shows several features of physiological activity, and mimics the in vivo situation quite closely (21, 24). In this in vitro model, the apical side of the PCPEC layer mimics the ventricular compartment, whereas the basolateral side represents the blood side in vivo. For the characterization of the structural and functional properties of the in vitro blood-CSF barrier, different parameters were used. The TEERP and [14C]sucrose permeability were determined to characterize barrier tightness. Functional changes could be shown by the capacitance, the active fluid secretion, and the phenol red concentration in the upper (apical) chamber. Whereas the in vitro barrier was not affected after basolateral incubation with up to 25 μm MnCl2, tightness and function of the PCPEC monolayer were concentration-dependently disturbed after basolateral incubation with ≥50 μm MnCl2. Thus, TEERP and capacitance values decreased (Fig. 3, A and B), pointing to a barrier disruption and a decreased number of PCPECs microvilli, respectively. Moreover, fluid secretion was reduced (data not shown) and phenol red concentration increased on the apical side (Fig. 3C), indicating an adverse effect on the proper function of the organic anion transporter, which is driven by the Na+,K+-ATPase. Barrier leakage was additionally confirmed by the results of the [14C]sucrose permeability studies (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 3.

Mn and in vitro blood-CSF barrier. A and B, impact of MnCl2 on the barrier integrity (TEERP) (A) and the capacitance (B) after basolateral MnCl2 incubation. Data, expressed as percentage of start value, represent mean values of at least three independent determinations with three replicates each with S.D. < ±10%. Mean TEERP and capacitance values of control cells were 801 ± 96 ohms*cm2 and 3.75*10−6 ± 2.09*10−7microfarads/cm2, respectively. C, phenol red concentration measured at 558 nm after 72-h basolateral MnCl2 incubation. Shown are mean values of least three independent determinations with three replicates ± S.D. (error bars). D, influence of MnCl2 on the TEERP values after apical MnCl2 incubation. Data, expressed as percentage of start value, represent mean values of at least three independent determinations with three replicates with S.D. < ±10%.

FIGURE 4.

Mn transfer across the in vitro blood-CSF barrier. A and B, Mn transfer after MnCl2 incubation of the basolateral compartment (influx studies) (A) or the apical compartment (efflux studies) (B). Data are expressed as percentage of the respective incubated MnCl2 concentration; open symbols represent quantified Mn concentrations in the apical, filled symbols in the basolateral compartment. C, Mn permeability coefficients and respective permeability coefficients of the permeability marker [14C]sucrose after 72-h MnCl2 basolateral or apical incubation. Due to missing linearity basolateral-to-apical, Mn permeability coefficient cannot be calculated. D, Mn permeability after concurrent MnCl2 incubation of both compartments. A–D, data represent mean values of at least three independent determinations with three replicates each ± S.D. (error bars). a, apical compartment; b, basolateral compartment; a → b, apical-to-basolateral transfer; b → a, basolateral-to-apical transfer.

Similar to the BBB in vitro model, in the blood-CSF barrier model Mn affected barrier integrity stronger after incubation on the blood side. After apical exposure, an impairment of the barrier tightness (Fig. 3D) and function (data not shown) was not visible until 200 μm MnCl2.

The time profiles of the basolateral-to-apical Mn transfer (Fig. 4A) and apical-to-basolateral Mn transfer (Fig. 4B) clearly demonstrate a higher transfer rate from basolateral incubated Mn into the apical compartment compared with the other direction. In case of basolateral incubation with ≤50 μm MnCl2, after 48 h of incubation Mn accumulated in the brain facing compartment, whereas after barrier disruption by 200 μm MnCl2, a concentration equation was achieved between the compartments (Fig. 4A). Because of the missing linear correlation, the basolateral-to-apical Mn transfer could not be expressed as permeability coefficient. Very interestingly, only approximately 20% of the apical dose applied (50, 200 μm MnCl2) reached the basolateral compartment (Fig. 4B) corresponding to permeability coefficients of approximately 1*10−6 cm/s (Fig. 4C). Further studies, applying an equal MnCl2 concentration (10 μm) in each compartment, demonstrate a Mn accumulation in the apical compartment (Fig. 4D). This clearly points to an active transport mechanism. In the case of a parallel incubation with 200 μm MnCl2, due to a barrier disruption, a concentration equation was achieved between the compartments (Fig. 4D).

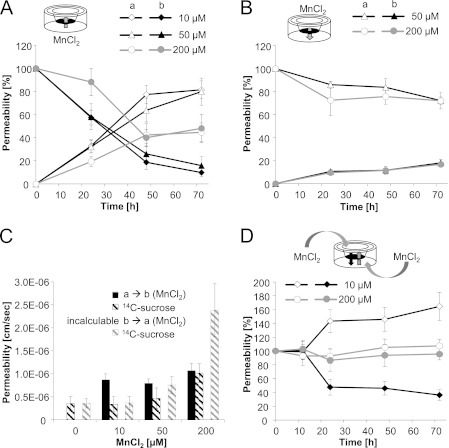

To identify possible transport mechanisms for Mn cellular uptake, the well characterized DMT1 inhibitor NSC306711 (31), incubated immediately prior MnCl2 (10, 25 μm) at the basolateral compartment, was used. Considering experiments with fully intact barriers in the presence of ≤50 μm NSC306711, Mn basolateral-to-apical transfer was not significantly different compared with the studies without the inhibitor (data not shown).

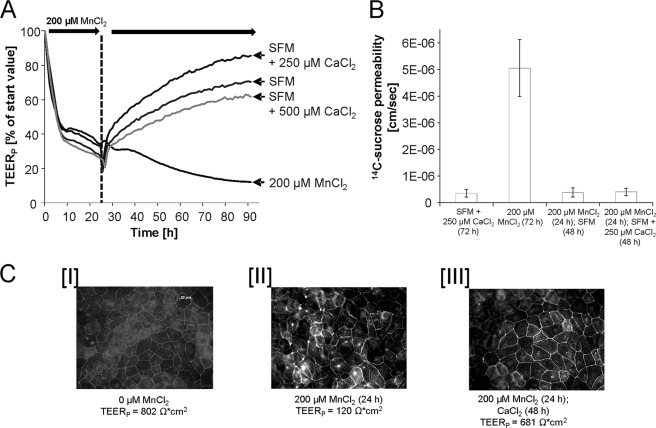

Effect of Ca on Manganese-induced Blood-CSF Barrier Disturbance

Further studies determining the impact of calcium (Ca) on Mn-induced disturbance of blood-CSF barrier properties refer to a reconstitution of barrier properties by Ca postincubation. Thus, filters of the in vitro blood-CSF barrier model were treated with 200 μm MnCl2 at the basolateral compartment to strongly disturb barrier integrity and function. After 24 h of MnCl2 incubation, the basolateral medium was replaced with SFM (containing approximately 1000 μm Ca) or CaCl2-enriched medium (SFM + 250 or 500 μm Ca). In case of a postincubation with SFM or Ca-enriched SFM, a reconstitution of the barrier tightness was clearly visible as measured by an increase of the respective TEERP values (Fig. 5A). Moreover, capacitance values, active fluid secretion to the apical compartment, and transport of phenol red to the basolateral compartment increased again (data not shown). Concordantly, the [14C]sucrose studies revealed the restored barrier tightness after Ca postincubation (Fig. 5B). As expected, the replacement of the basolateral medium did not result in a reduction of the apical Mn concentration (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of Ca on the Mn-induced blood-CSF barrier disturbance. A and B, relative TEERP values (A) and respective [14C]sucrose permeability coefficients (B) after 24-h preincubation with 200 μm MnCl2, medium exchange at the basolateral compartment and postincubation without/with Ca-enriched medium (Ca concentration in medium of the CP epithelial cells: 1013 μm). Shown are data from one representative experiment (n = 3 with S.D. < ±10% (error bars)). C, immunocytochemical staining of occludin. I, nontreated (TEERP = 802 ohms*cm2) barriers; II, barriers after basolateral incubation with 200 μm MnCl2 for 24 h (TEERP = 120 ohms*cm2); and III, barriers after 24-h basolateral preincubation with MnCl2 and 48 h after incubation with Ca-enriched SFM (SFM + 250 μm CaCl2 (TEERP = 681 ohms*cm2).

The barrier properties of the epithelial cell monolayer were further investigated by the immunocytochemical analysis of occludin, a protein that is a central functional component of tight junctions (32). In nonexposed PCPECs, occludin staining appeared (33) in clear lines, without any fuzzy appearance, and cell borders were mostly straight and not serrated (Fig. 5CI). In contrast, filters treated for 24 h with 200 μm MnCl2 (Fig. 5CII) showed more serrated and perforated cell borders, indicating that tight junctions were not fully closed anymore. Apparently, the subsequent replacement of the basolateral MnCl2-incubated medium with Ca-enriched SFM resulted in a relock of the tight junctions, leaving only a few areas with not fully closed tight junctions (Fig. 5CIII). Comparable studies using the in vitro BBB model, in which 200 μm MnCl2 were preincubated to the apical compartment for 24 h and then postincubated with SFM or Ca-enriched SFM, demonstrate no reversibility of the Mn- induced effects in this model (data not shown).

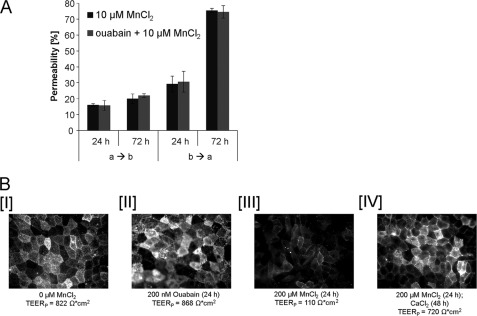

Manganese and Na+,K+-ATPase in Blood-CSF Barrier

The role of Na+-K+-ATPase in Mn transfer was studied via a basolateral incubation with its selective inhibitor ouabain immediately prior to apical or basolateral incubation with 10 μm MnCl2. Within the following 72 h neither the basolateral-to-apical nor the apical-to-basolateral transfer was significantly different from the studies in the absence of ouabain (Fig. 6A). At the same time, Na+-K+-ATPase activity was clearly affected, as measured by an increase of the phenol red concentration on the apical side.

FIGURE 6.

Mn transfer across the in vitro blood-CSF barrier without/with the Na+,K+-ATPase-inhibitor ouabain (200 nm). A, mean values of three determinations ± S.D. (error bars). B, immunocytochemical staining of the Na+,K+-ATPase. I, nontreated (TEERP = 822 ohms*cm2) barriers; II, barriers after basolateral incubation with 200 nm ouabain for 72 h (TEERP = 868 ohms*cm2); III, barriers after basolateral incubation with 200 μm MnCl2 for 24 h (TEERP = 110 ohms*cm2); and IV, barriers after 24-h basolateral preincubation with MnCl2 and 48 h after incubation with Ca-enriched SFM (SFM + 250 μm CaCl2 (TEERP = 720 ohms*cm2). a → b, apical-to-basolateral transfer; b → a, basolateral-to-apical transfer.

Immunological Na+-K+-ATPase staining reveals that in nonexposed as well as ouabain-treated (24–72 h) cells Na+,K+-ATPase is located at the luminal surface (Fig. 6B, I and II). In contrast, filters that were treated for 24 h with 200 μm MnCl2 in the basolateral compartment had a significantly reduced Na+,K+-ATPase signal (Fig. 6BIII); a 72-h incubation with MnCl2 showed similar effects (data not shown). After an additional 48 h postincubation with CaCl2, Na+,K+-ATPase is located again at the luminal surface (Fig. 6BIV).

DISCUSSION

A crucial poorly understood step in Mn-induced neurotoxicity is its effect on and its transfer across the two brain-regulating interfaces, the BBB and the blood-CSF barrier. In the present study, well established porcine-based cell culture models were used, with PBCECs and PCPECs as structural basis of the BBB and the blood-CSF barrier, respectively. It is well known that pig brain shows more similarities to human brain, with respect to size, anatomy growth, and development compared with brains of other laboratory animals including rodents. This makes porcine in vitro systems important experimental models to be considered within neurosciences (34–36). Additionally, these primary cultures obtained from freshly slaughtered pigs have the clear advantage of being an alternative approach to the costly, time-consuming and ethically questionable systems derived from experimental animals.

Regarding the in vitro BBB studies in the present work, the data clearly show that barrier leakage caused by ≥200 μm MnCl2 in the apical, blood-resembling compartment correlated with Mn cytotoxicity. Results obtained from TEERN measurements were confirmed by [14C]sucrose permeability studies, which similarly indicated an alteration of paracellular tightness in the presence of elevated Mn concentrations. In contrast, a basolateral MnCl2 incubation, which simulates an in vivo situation after Mn accumulation in specific brain regions (37), did not affect barrier integrity up to 500 μm MnCl2, a concentration clearly being not exposure-relevant anymore. In brain tissues, physiological Mn concentrations range from 2 to 8 μm, but can be increased severalfold upon overexposure (38, 39). Together with the observed small Mn efflux in case of high Mn concentrations (≥100 μm) to the apical compartment (blood side), these results are in agreement with in vivo studies, in which Mn after entering the brain, strongly persists, and therefore accumulates in the brain (40, 41). Evidence suggests that brain Mn efflux across the BBB proceeds through slow diffusion (42), which is supported by our data. In the case of lower applied MnCl2 concentrations (≤50 μm), comparable apical-to-basolateral (influx) and basolateral-to-apical (efflux) transfer rates after incubation in one of the respective compartments as well as the missing Mn accumulation in one compartment after parallel incubation on both, apical and basolateral, sides, strongly point to a passive transfer process of Mn across the BBB. The influx permeability coefficient across the BBB for divalent Mn is, for example, comparable with the influx permeability coefficient of morphine in the same in vitro model (25).

One very important outcome of the present work is the fact that in direct comparison with the in vitro BBB model, the blood-CSF barrier model was much more sensitive toward Mn. The disturbance of barrier properties was not caused by Mn cytoxicity. The observed higher cytotoxic resistance and Mn bioavailability in PCPECs compared with PBCECs suit with in vivo studies, demonstrating a several orders of magnitude higher Mn uptake and accumulation by the CP in comparison with other brain regions (43).

Similar to the BBB model, blood-CSF barrier properties were most strongly affected after MnCl2 incubation on the blood side, which is in the blood-CSF barrier model the basolateral compartment. Thus, barrier tightness and functions were strongly disturbed after basolateral incubation with ≥50 μm MnCl2 and apical incubation with ≥200 μm MnCl2, respectively. Moreover, apical-to-basolateral Mn transfer was much lower compared with basolateral-to-apical transfer, which has very recently also been reported in a rat-based blood-CSF barrier model (44).

The observed Mn-induced decrease of active fluid secretion and phenol red transport might be due to an inhibition of Na+,K+-ATPase function by Mn. In the CP epithelium, the Na+,K+-ATPase is the driving force of the active fluid secretion and is furthermore a major player of various active transport properties including transport of phenol red from apical to basolateral compartment. Disturbance of Na+,K+-ATPase function might result from an inhibition of the Na+,K+-ATPase activity, which has been described in neuroblastoma cells or liver tissue by Mn before (45, 46), but might also be due to Na+,K+-ATPase internalization following a phosphorylation of a Na+,K+-ATPase subunit. The immunocytochemistry studies carried out in this work strongly argue for such a Na+,K+-ATPase internalization in the presence of high MnCl2 concentrations. Na+,K+-ATPase has also been reported to be inhibited by ROS in primary cultures (47), and it is generally known that Mn overexposure induces a transient increase in the cellular ROS level of brain cells (48, 49). Additionally, chronic Mn exposure might alter systematic homeostasis of calcium, leading to a further impairment of Na+,K+-ATPase function (14, 50). As a further barrier integrity disturbing mechanism, occludin immunocytochemistry studies reveal a disturbance of tight junction structure, which might also be partly caused by an inhibition of Na+,K+-ATPase function (51).

Regarding the type of Mn influx via the blood-CSF barrier, our data argue for an active transport mechanism. As summarized in Ref. 44, many transporters are expressed in the CP and are therefore discussed to contribute to Mn transport. Because DMT1 has been shown to be present in the blood-CSF barrier in several studies and Mn exposure resulted in an increased DMT1 expression in rats (52), the present study intended to assess the role of DMT1 in Mn transfer processes. However, applying the DMT1 inhibitor NSC306711, our data show that in the applied in vitro system DMT1 is not the major transporter for Mn uptake into the brain via the blood-CSF barrier. These data account with studies in which Mn uptake was not significantly reduced in homozygous Belgrade rat (b/b) with no functional DMT1 expression (53). The application of the selective Na+,K+-ATPase inhibitor ouabain did not result in an decrease of Mn transfer across the blood-CSF barrier, indicating that Mn transfer is independent of Na+,K+-ATPase function, which has been published by Crossgrove and Yokel before (54). In contrast, recent evidence has clearly shown that in a rat model upon Mn treatment, MTP1 (also named ferroportin 1) is visibly translocated from the diffuse distribution in the cytosol to apical microvilli of the CP and transports excess amounts of intracellular Mn toward the CSF. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that similar to MTP1, the direction of cellular TfR trafficking was also toward the CSF (55).

Mn uptake in the CP has been reported to be stronger than in other brain regions, whereas Mn concentrations in CSF are comparably low, indicating no strong Mn efflux from CP into CSF. Thus, physiological Mn concentrations in CSF are comparable with serum concentrations, ranging from 1.0 ± 0.5 μg/liter in nonexposed patients to severalfold higher levels in exposed patients (56, 57). This fact might have contributed to the assumption frequently discussed in literature that Mn enters the brain at normal physiological plasma concentrations across the capillary endothelium, whereas at high plasma concentrations, Mn transfer across the CP appears to predominate (3, 43). However, taking into account the data in this work, in which for the first time Mn transfer across the two barriers has been compared in one study, this assumption has to be critically assessed.

Moreover, in the present study we showed for the first time that a basolateral postincubation with Ca can compensate for Mn-induced disturbance of blood-CSF barrier properties, restoring both barrier tightness and function. Intracellular Ca homeostasis has a strong impact on tight junction integrity, and a decrease in intracellular Ca levels has been shown to alter subcellular localization of occludin and changes Zo-1/actin binding (58). In biological systems, Mn2+ has the same charge and relative size as Ca2+, and a number of reports have shown that Mn and Ca trafficking, recruitment, and storage are regulated by the same ion pumps and intracellular compartments. Therefore, Mn2+ might compete with Ca2+ in uptake studies (59, 60), thereby disturb intracellular Ca homeostasis and correct tight junction formation and/or localization (26, 61). This effect might be reversible by elevated Ca concentrations, as indicated by the present occludin immunofluorescence studies. Moreover, a recovery of Na+,K+-ATPase function, which is also coupled to intracellular Ca homeostasis, might also contribute to the observed Ca-mediated reversibility of Mn-induced barrier disturbance. Further studies should examine these interactions in more detail, which might also help to understand the mechanism of Mn-induced barrier disruption.

CONCLUSION

By the use of state-of-the in vitro barrier models effects of Mn on the integrity of the blood-brain and blood-CSF barrier as well as Mn transfer across these two barriers in both directions were compared in one study for the first time. In summary, both the observed stronger Mn sensitivity of the in vitro blood-CSF barrier and the observed site-directed, most probably active Mn transport toward the brain facing compartment, reveal that, in contrast to the general assumption in literature, the blood-CSF barrier might be the major route for Mn into the brain after oral Mn intake.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Developmental Therapeutics Program of the National Cancer Institute for procuring the test substance NSC306711 used in this study. We also appreciate Dr. Aaron Bowman for helpful discussions regarding the NSC306711 studies.

This work was supported by the Graduate School of Chemistry (Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Germany).

- BBB

- blood-brain barrier

- CSF

- cerebrospinal fluid

- CP

- choroid plexus

- DIV

- day in vitro

- DMT1

- divalent metal transporter 1

- FIA-ICP-QMS

- flow injection inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry with quadrupole mass analyzer

- PBCEC

- porcine brain capillary endothelial cell

- PCPEC

- porcine choroid plexus cell

- SFM

- serum-free medium

- TEERN

- transendothelial electrical resistance

- TEERP

- transepithelial electrical resistance

- TfR

- transferrin receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Santamaria A. B. (2008) Manganese exposure, essentiality and toxicity. Indian J. Med. Res. 128, 484–500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olanow C. W. (2004) Manganese-induced parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1012, 209–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aschner M., Guilarte T. R., Schneider J. S., Zheng W. (2007) Manganese: recent advances in understanding its transport and neurotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 221, 131–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bowler R. M., Gysens S., Diamond E., Nakagawa S., Drezgic M., Roels H. A. (2006) Manganese exposure: neuropsychological and neurological symptoms and effects in welders. Neurotoxicology 27, 315–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guilarte T. R. (2010) Manganese and Parkinson's disease: a critical review and new findings. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 1071–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pan D., Caruthers S.D., Senpan A., Schmieder A. H., Wickline S., Lanza G. M. (2010) Revisiting an old friend: manganese-based MRI contrast agents. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 10.1002/wnan.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nagatomo S., Umehara F., Hanada K., Nobuhara Y., Takenaga S., Arimura K., Osame M. (1999) Manganese intoxication during total parenteral nutrition: report of two cases and review of the literature. J. Neurol. Sci. 162, 102–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gerber G. B., Léonard A., Hantson P. (2002) Carcinogenicity, mutagenicity and teratogenicity of manganese compounds. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 42, 25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flynn M. R., Susi P. (2009) Neurological risks associated with manganese exposure from welding operations: a literature review. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 212, 459–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abbott N. J., Patabendige A. A., Dolman D. E., Yusof S. R., Begley D. J. (2010) Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol. Dis. 37, 13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Strazielle N., Ghersi-Egea J. F. (2000) Choroid plexus in the central nervous system: biology and physiopathology. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 59, 561–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rabin O., Hegedus L., Bourre J. M., Smith Q. R. (1993) Rapid brain uptake of manganese(II) across the blood-brain barrier. J. Neurochem. 61, 509–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fitsanakis V. A., Piccola G., Marreilha dos Santos A. P., Aschner J. L., Aschner M. (2007) Putative proteins involved in manganese transport across the blood-brain barrier 1ier. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 26, 295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bowman A. B., Kwakye G. F., Hernández E. H., Aschner M. (2011) Role of manganese in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 25, 191–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nagasawa K., Escartin C., Swanson R. A. (2009) Astrocyte cultures exhibit P2X7 receptor channel opening in the absence of exogenous ligands. Glia 57, 622–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yokel R. A. (2006) Blood-brain barrier flux of aluminum, manganese, iron and other metals suspected to contribute to metal-induced neurodegeneration. J. Alzheimers Dis. 10, 223–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aschner M., Gannon M. (1994) Manganese (Mn) transport across the rat blood-brain barrier: saturable and transferrin-dependent transport mechanisms. Brain Res. Bull. 33, 345–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crossgrove J. S., Allen D. D., Bukaveckas B. L., Rhineheimer S. S., Yokel R. A. (2003) Manganese distribution across the blood-brain barrier. I. Evidence for carrier-mediated influx of manganese citrate as well as manganese and manganese transferrin. Neurotoxicology 24, 3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. von Wedel-Parlow M., Wölte P., Galla H. J. (2009) Regulation of major efflux transporters under inflammatory conditions at the blood-brain barrier in vitro. J. Neurochem. 111, 111–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Angelow S., Zeni P., Galla H. J. (2004) Usefulness and limitation of primary cultured porcine choroid plexus epithelial cells as an in vitro model to study drug transport at the blood-CSF barrier. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 56, 1859–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gath U., Hakvoort A., Wegener J., Decker S., Galla H. J. (1997) Porcine choroid plexus cells in culture: expression of polarized phenotype, maintenance of barrier properties and apical secretion of CSF-components. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 74, 68–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Franke H., Galla H. J., Beuckmann C. T. (1999) An improved low-permeability in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier: transport studies on retinoids, sucrose, haloperidol, caffeine and mannitol. Brain Res. 818, 65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kröll S., El-Gindi J., Thanabalasundaram G., Panpumthong P., Schrot S., Hartmann C., Galla H. J. (2009) Control of the blood-brain barrier by glucocorticoids and the cells of the neurovascular unit. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1165, 228–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haselbach M., Wegener J., Decker S., Engelbertz C., Galla H. J. (2001) Porcine choroid plexus epithelial cells in culture: regulation of barrier properties and transport processes. Microsc. Res. Tech. 52, 137–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lohmann C., Hüwel S., Galla H. J. (2002) Predicting blood-brain barrier permeability of drugs: evaluation of different in vitro assays. J. Drug Target 10, 263–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lischper M., Beuck S., Thanabalasundaram G., Pieper C., Galla H. J. (2010) Metalloproteinase-mediated occludin cleavage in the cerebral microcapillary endothelium under pathological conditions. Brain Res. 1326, 114–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hakvoort A., Haselbach M., Wegener J., Hoheisel D., Galla H. J. (1998) The polarity of choroid plexus epithelial cells in vitro is improved in serum-free medium. J. Neurochem. 71, 1141–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Repetto G., del Peso A., Zurita J. L. (2008) Neutral red uptake assay for the estimation of cell viability/cytotoxicity. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1125–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wehe C. A., Bornhorst J., Holtkamp M., Sperling M., Galla H. J., Schwerdtle T., Karst U. (2011) Fast and low sample consuming quantification of manganese in cell nutrient solutions by flow injection ICP-QMS. Metallomics 3, 1291–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Michalke B., Halbach S., Nischwitz V. (2007) Speciation and toxicological relevance of manganese in humans. J. Environ. Monit. 9, 650–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buckett P. D., Wessling-Resnick M. (2009) Small molecule inhibitors of divalent metal transporter-1. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 296, G798–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McCarthy K. M., Skare I. B., Stankewich M. C., Furuse M., Tsukita S., Rogers R. A., Lynch R. D., Schneeberger E. E. (1996) Occludin is a functional component of the tight junction. J. Cell Sci. 109, 2287–2298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Franke H., Galla H., Beuckmann C. T. (2000) Primary cultures of brain microvessel endothelial cells: a valid and flexible model to study drug transport through the blood-brain barrier in vitro. Brain Res. Brain Res. Protoc. 5, 248–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Swanson L. W. (1995) Mapping the human brain: past, present, and future. Trends Neurosci. 18, 471–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lind N. M., Moustgaard A., Jelsing J., Vajta G., Cumming P., Hansen A. K. (2007) The use of pigs in neuroscience: modeling brain disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 31, 728–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Podolska A., Kaczkowski B., Kamp Busk P., Søkilde R., Litman T., Fredholm M., Cirera S. (2011) MicroRNA expression profiling of the porcine developing brain. PLoS One 6, e14494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Santamaria A. B., Sulsky S. I. (2010) Risk assessment of an essential element: manganese. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 73, 128–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pal P. K., Samii A., Calne D. B. (1999) Manganese neurotoxicity: a review of clinical features, imaging and pathology. Neurotoxicology 20, 227–238 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu X., Sullivan K. A., Madl J. E., Legare M., Tjalkens R. B. (2006) Manganese-induced neurotoxicity: the role of astroglial-derived nitric oxide in striatal interneuron degeneration. Toxicol. Sci. 91, 521–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dastur D. K., Manghani D. K., Raghavendran K. V. (1971) Distribution and fate of 54Mn in the monkey: studies of different parts of the central nervous system and other organs. J. Clin. Invest. 50, 9–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Takeda A., Sawashita J., Okada S. (1995) Biological half-lives of zinc and manganese in rat brain. Brain Res. 695, 53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yokel R. A., Crossgrove J. S., Bukaveckas B. L. (2003) Manganese distribution across the blood-brain barrier. II. Manganese efflux from the brain does not appear to be carrier mediated. Neurotoxicology 24, 15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murphy V. A., Wadhwani K. C., Smith Q. R., Rapoport S. I. (1991) Saturable transport of manganese(II) across the rat blood-brain barrier. J. Neurochem. 57, 948–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schmitt C., Strazielle N., Richaud P., Bouron A., Ghersi-Egea J. F. (2011) Active transport at the blood-CSF barrier contributes to manganese influx into the brain. J. Neurochem. 117, 747–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chtourou Y., Trabelsi K., Fetoui H., Mkannez G., Kallel H., Zeghal N. (2011) Manganese induces oxidative stress, redox state unbalance and disrupts membrane bound ATPases on murine neuroblastoma cells in vitro: protective role of silymarin. Neurochem. Res. 36, 1546–1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huang P., Li G., Chen C., Wang H., Han Y., Zhang S., Xiao Y., Zhang M., Liu N., Chu J., Zhang L., Sun Z. (2012) Differential toxicity of Mn2+ and Mn3+ to rat liver tissues: oxidative damage, membrane fluidity and histopathological changes. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 64, 197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rodrigo R., Bächler J. P., Araya J., Prat H., Passalacqua W. (2007) Relationship between (Na + K)-ATPase activity, lipid peroxidation and fatty acid profile in erythrocytes of hypertensive and normotensive subjects. Mol. Cell Biochem. 303, 73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Milatovic D., Zaja-Milatovic S., Gupta R. C., Yu Y., Aschner M. (2009) Oxidative damage and neurodegeneration in manganese-induced neurotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 240, 219–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Marreilha Dos Santos A. P., Lopes Santos M., Batoréu M. C., Aschner M. (2011) Prolactin is a peripheral marker of manganese neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 1382, 282–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Therien A. G., Blostein R. (2000) Mechanisms of sodium pump regulation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C541–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rajasekaran S. A., Hu J., Gopal J., Gallemore R., Ryazantsev S., Bok D., Rajasekaran A. K. (2003) Na,K-ATPase inhibition alters tight junction structure and permeability in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 284, C1497–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang X., Li G. J., Zheng W. (2006) Up-regulation of DMT1 expression in choroidal epithelia of the blood-CSF barrier following manganese exposure in vitro. Brain Res. 1097, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Crossgrove J., Zheng W. (2004) Manganese toxicity upon overexposure. NMR Biomed 17, 544–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Crossgrove J. S., Yokel R. A. (2005) Manganese distribution across the blood-brain barrier. IV. Evidence for brain influx through store-operated calcium channels. Neurotoxicology 26, 297–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang X., Miller D. S., Zheng W. (2008) Intracellular localization and subsequent redistribution of metal transporters in a rat choroid plexus model following exposure to manganese or iron. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 230, 167–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nischwitz V., Berthele A., Michalke B. (2008) Speciation analysis of selected metals and determination of their total contents in paired serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples: an approach to investigate the permeability of the human blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier. Anal. Chim. Acta 627, 258–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hozumi I., Hasegawa T., Honda A., Ozawa K., Hayashi Y., Hashimoto K., Yamada M., Koumura A., Sakurai T., Kimura A., Tanaka Y., Satoh M., Inuzuka T. (2011) Patterns of levels of biological metals in CSF differ among neurodegenerative diseases. J. Neurol. Sci. 303, 95–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ye J., Tsukamoto T., Sun A., Nigam S. K. (1999) A role for intracellular calcium in tight junction reassembly after ATP depletion-repletion. Am. J. Physiol. 277, F524–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ambudkar I. S., Lockwich T., Hiramatsu Y., Baum B. J. (1992) Calcium entry in rat parotid acinar cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 114, 73–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yokel R. A. (2009) Manganese flux across the blood-brain barrier. Neuromolecular Med. 11, 297–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wong V. (1997) Phosphorylation of occludin correlates with occludin localization and function at the tight junction. Am. J. Physiol. 273, C1859–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]