Background: G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) are important regulators of receptor signaling although little is known about their functions beyond their receptor modifying activities.

Results: GRK5 binds and phosphorylates nucleophosmin.

Conclusion: GRK5 and polo-like kinase 1 coordinately regulate nucleophosmin phosphorylation and cell sensitivity to inhibitor-induced apoptosis.

Significance: GRKs play an important role in regulating normal cell functions such as cell cycle regulation and apoptosis.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cell Cycle, Drug Resistance, Enzyme Inhibitors, Nucleus, Phosphorylation, Protein Kinases, GRK

Abstract

G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) phosphorylate activated G protein-coupled receptors, leading to their desensitization and endocytosis. GRKs have also been implicated in phosphorylating other classes of proteins and can localize in a variety of cellular compartments, including the nucleus. Here, we attempted to identify potential nuclear substrates for GRK5. Our studies reveal that GRK5 is able to interact with and phosphorylate nucleophosmin (NPM1) both in vitro and in intact cells. NPM1 is a nuclear protein that regulates a variety of cell functions including centrosomal duplication, cell cycle control, and apoptosis. GRK5 interaction with NPM1 is mediated by the N-terminal domain of each protein, and GRK5 primarily phosphorylates NPM1 at Ser-4, a site shared with polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1). NPM1 phosphorylation by GRK5 and PLK1 correlates with the sensitivity of cells to undergo apoptosis with cells having higher GRK5 levels being less sensitive and cells with lower GRK5 being more sensitive to PLK1 inhibitor-induced apoptosis. Taken together, our results demonstrate that GRK5 phosphorylates Ser-4 in nucleophosmin and regulates the sensitivity of cells to PLK1 inhibition.

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs)3 are a family of seven serine/threonine protein kinases that phosphorylate activated G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (1). GRK-mediated receptor phosphorylation promotes the binding of arrestins, leading to the desensitization and endocytosis of the receptor (1, 2). In addition to their function in regulating GPCRs, GRKs also phosphorylate non-receptor substrates, thus potentially regulating a variety of cellular processes (3). Some examples of non-GPCR substrates include tubulin (4, 5), synucleins (6), phosducin (7), DREAM (8), p38 (9), IκBα (10), NFκB1 p105 (11), ezrin (12), HDAC5 (13), β-arrestin-1 (14), p53 (15, 16), and Hip (17). These additional activities may be important because GRK levels vary in many pathological conditions including cardiovascular disease (18–21), cancer (22–25), and various neurological disorders (26–29). Further expanding the scope of GRK function is the finding that GRK5 and GRK6 are found in the nucleus (13, 30, 31). Interestingly, the ability of GRK5 to localize in the nucleus may be regulated by Gq signaling (13, 30), whereas the nuclear localization of GRK6 may be regulated by palmitoylation (31). These studies suggest a novel, underexplored, location within cells where GRKs may mediate their effects.

To identify potential nuclear targets for GRKs, we initially used in vitro approaches such as chromatography and mass spectrometry to identify potential substrates. Herein, we present our results identifying the nuclear protein nucleophosmin (NPM1), also known as B23, as a novel substrate for GRK5. NPM1 belongs to the nucleoplasmin family of proteins, made up of nucleophosmin, nucleoplasmin (NPM2), and NPM3 (32). An N-terminal core structure, which is required for oligomerization, is shared within members of this family. There are 2 splice variants of NPM1, B23.1 and B23.2, with B23.1 containing an additional 35 amino acids in the C terminus (33). NPM1 is involved in a variety of functions, including the regulation of centrosomal duplication, the cell cycle, mitosis, apoptosis, and RNA and DNA replication, and it also serves as a chaperone for proteins such as histones. NPM1 is also overexpressed in a number of cancers and, thus, is a potential target within the cancer field (34).

In this report we demonstrate that NPM1 is phosphorylated by GRK5 both in vitro and in cells, with Ser-4 being the major phosphorylation site. Interestingly, GRK5-depleted cells were more sensitive to undergoing cell death from polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) inhibition, and this increased susceptibility corresponded to decreased NPM1 phosphorylation. Conversely, cells with higher GRK5 levels exhibited reduced sensitivity to PLK1 inhibition. Taken together, our results demonstrate that GRK5 phosphorylates Ser-4 in nucleophosmin and regulates the sensitivity of cells to PLK1 inhibition.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

A human NPM1 cDNA was a generous gift from Dr. Stephen Peiper (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA). Monoclonal anti-NPM1 and propidium iodide were purchased from Invitrogen, whereas protein A/G beads and antibodies for GRK2, GRK5, and nucleolin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-HSP90 and calnexin were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY), whereas anti-GRK4–6 was from Millipore (Billerica, MA). 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI), anti-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), anti-Na+/K+ ATPase antibodies, purified PLK1, and 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (FUDR) were from Sigma. All media were purchased from Mediatech, Inc. (Manassas, VA). BI 2536 and GSK461364 were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX), dissolved in water, aliquoted, and stored at −20 °C until use. Anti-phospho-Ser-4 and anti-phospho-Thr-199 NPM1 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA).

Identification of Nuclear GRK Substrates

A HeLa cell nuclear extract prepared from ten 15-cm dishes of confluent cells was diluted to 20 ml with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, and loaded on a 3-ml Q-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) column equilibrated with buffer A (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol) containing 50 mm NaCl. The column was washed with the same buffer and then eluted with a 30-ml linear gradient from 50 to 700 mm NaCl in buffer A. All purification steps were performed at 4 °C. For phosphorylation reactions, 10 μl of each fraction from the Q-Sepharose elution was incubated with or without 200 nm purified GRK2 or GRK5 in 20 μl of buffer B (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 4 mm MgCl2) containing 0.1 mm ATP and 1–2 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP. Reactions were incubated for 30 min at 30 °C, stopped with SDS sample buffer, and electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were visualized by Coomassie Blue staining and autoradiography. This analysis identified a GRK5 substrate of ∼40 kDa (p40) that eluted at ∼600 mm NaCl. To identify p40, an aliquot of the peak fraction was electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and stained by Coomassie Blue, and the ∼40-kDa protein was excised, proteolyzed with trypsin, and analyzed by mass spectrometry. A subsequent data base search identified the 40-kDa protein as nucleophosmin.

Cell Culture

HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 mm HEPES and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen). MDA-MB-231 cells were from American Tissue Culture Collection and were cultured in DMEM without sodium pyruvate supplemented with 10% FBS. T47D and SKBR3 cells were from Dr. Hallgeir Rui (Thomas Jefferson University). T47D cells were grown in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, whereas SKBR3 were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 μm glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, and 10% FBS. BT549 cells were from Dr. Erik Knudsen (Thomas Jefferson University) and were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 μm glutamine and 10% FBS. MCF7 cells were obtained from Dr. Michael Lisanti (Thomas Jefferson University) and were cultured in minimum essential media containing 10% FBS. BI 2536 treatments were performed in cell-specific growth media.

To create stable HeLa cell lines, shRNA constructs specific for GRK5 along with a scrambled control shRNA were purchased from Sigma, and 10 μg of plasmid were transfected into HeLa cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were then selected in 2 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma) to obtain a stably expressing population as previously described (16). HeLa cells with stable GRK5 knockdown were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10 mm HEPES, 10% FBS, and 2 μg/ml puromycin. The GRK5 shRNA sequence was 5′-ACGAGATGATAGAAACAGAAT-3′. For transient transfections, four GRK5 siRNAs were pooled together, and 60 pmol of the pool was used per transfection: 5′-CCAACACGGUCUUGCUGAA-3′, 5′-GGGAGAACCAUUCCACGAA-3′, 5′-CAAACCAUGUCAGCUCGAA-3′, and 5′-GAUUAUGGCCACAUUAGGA-3′. Control siRNA scrambled sequences were purchased from Dharmacon. To determine cell death, trypan blue (Mediatech) exclusion was used to count non-viable cells with percent cell death expressed as (# stained cells/# total cells) × 100.

Purification of NPM1

NPM1 from HeLa cell nucleoli was purified following a previously published method (35). For purification of His-tagged NPM1, a NPM1 cDNA was subcloned in-frame within the cloning site of pTrcHis A (Invitrogen) using BamHI and HindIII. NPM1 was expressed in Escherichia coli M16 cells (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Cells were grown in terrific broth to A600 = 0.6, induced with 0.1 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside, grown overnight at 30 °C, and then collected by centrifugation and frozen at −80 °C. Frozen cells were thawed, resuspended in buffer C (20 mm Tris-HCl, 0.5 m NaCl, 5% glycerol) supplemented with a protease inhibitor tablet without EDTA (Roche Applied Science), homogenized using a Polytron, sonicated, and centrifuged at 32,000 × g. The supernatant was then incubated with 10 ml of a 50% nickel resin slurry (Qiagen), washed with buffer C containing 50 mm imidazole, and eluted with buffer C containing 200 mm imidazole. Eluted His-tagged NPM1 was concentrated and then applied to a gel filtration column using Buffer B. Peak fractions were pooled, concentrated, and frozen at −80 °C. The purified protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining, and the concentration was determined by Bradford assay.

Glutathione S-Transferase (GST) Pulldown Assays

NPM1 cDNA was subcloned into pGEX vector 4T2 (GE Healthcare) using EcoRI and XhoI. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using a two-step PCR mutagenesis method. For GST-GRK5-(1–200) and GST-GRK5-(489–562), DNA sequences were generated using PCR and inserted within the BamHI-SalI fragment in the vector pGEX-4T-2 as previously described (36). Purification of GST-NPM1 and GST-GRK5 was done following previous methods (37). For GST-NPM1, GST fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells grown in Luria broth. The culture was induced with 100 μm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside and grown at 30 °C overnight. Cells were resuspended and sonicated in lysis buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mm NaCl, protease inhibitor mixture, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol) and centrifuged at 60,000 × g, and the GST fusion proteins were affinity-purified with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare). Protein purity was assessed by Coomassie Blue staining of SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford assay. Pulldown experiments were performed similar to published protocols (38). GST-GRK5-(1–200) and GST-GRK5-(489–562) were expressed in BL21(DE3) cells, induced with 100 μm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside, grown at 30 °C for 2 h, and purified in a similar fashion to GST-NPM1.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Cells were grown on poly-lysine-coated coverslips for 72 h in the presence or absence of 5 nm BI 2536, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X-100 in PBS (137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 10 mm Na2HPO4, 1.7 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.4). Cells were stained with DAPI, washed twice with PBS, mounted, and then examined on a Nikon Eclipse E800 fluorescence microscope using a Plan Fluor 60 × 14 oil objective. Images were collected using QED Camera software and processed with Adobe Photoshop and Image Pro Plus. The number of fragmented and elongated nuclei was scored and compared between treatments.

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation

Nuclear extracts were prepared following a previously published protocol (39). Briefly, cells were resuspended in a hypotonic buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 300 mm sucrose, 0.5 mm glycerol phosphate, 0.5 mm DTT), incubated on ice for 10 min, lysed for 30 s with 0.6% Nonidet P-40, and then centrifuged at 1000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant (cytosol) and particulate (nuclear) fractions were collected. The particulate fraction was washed vigorously 6× with PBS, then incubated with hypertonic buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mm MgCl2, 420 mm NaCl, 0.2 mm EDTA, 25% glycerol, 5 mm DTT, and protease inhibitors) on a shaker at 4 °C followed by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was used as the nuclear fraction. For whole cell lysates, cells were lysed by incubation in Triton lysis buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm EDTA containing protease inhibitors and PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor tablets (Roche Applied Science)) for 20 min at 4 °C followed by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 30 min. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay.

For co-immunoprecipitations, ∼100 μg of nuclear extract was immunoprecipitated by overnight incubation at 4 °C with 1 μg of anti-NPM1, anti-GRK5, or corresponding antibody isotypes, previously cross-linked to 20 μl of protein A/G beads using dimethyl pimelimidate. Beads were then washed 6× with PBS and eluted by boiling in SDS sample buffer. For immunoblotting, samples were electrophoresed and separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, blocked with 5% skim milk in TBS, 0.1% Tween 20, and blotted with the appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. Immunoblots were incubated with SuperSignal Enhanced Chemiluminescent (Thermo Scientific) substrate and developed.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

GRK2 and GRK5 were purified as described (40, 41), whereas purified PLK1 was from Sigma. Protein phosphorylation was detected using either [γ-32P]ATP labeling or phospho-specific antibodies, and assays were performed similar to previous protocols (6). Briefly, indicated amounts of purified nucleophosmin were incubated with or without indicated amounts of purified GRK2 or GRK5 in 20 μl of buffer B with 0.1 mm ATP and 1–2 μCi [γ-32P]ATP. Reactions were incubated for the indicated times at 30 °C, stopped with SDS sample buffer, and electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were visualized by autoradiography. Radioactivity was quantified by excising Coomassie Blue-stained bands from the dried gels and counting in a scintillation counter.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were treated for 72 h with 0–10 nm BI 2536, collected, fixed with 70% ethanol, rehydrated with PBS, and then stained with propidium iodide solution (0.2 mg/ml DNase-free RNase, 1 mg/ml propidium iodide, and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS). An additional series of studies involved a double thymidine block followed by release of the cells into 60 nm BI 2536. In these studies, BI 2536 effectively retarded both control and GRK5 shRNA cells at 10 h, with ∼90% of cells trapped at G2/M as determined by flow cytometry analysis (% cells at G2/M at 10 h: control, 87.5 ± 1.7%; GRK5 shRNA, 87.9 ± 1.3%, n = 4). All samples were analyzed on a Beckman Coulter Epics XL-MCL Flow Cytometer.

Statistical Analysis

All statistics were performed using a Student's t test.

RESULTS

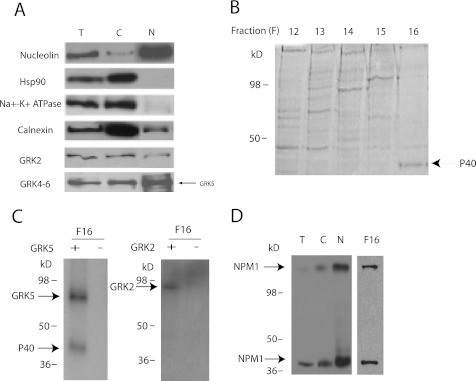

Since previous studies showed that GRK5 can localize in the nucleus (13, 30), we attempted to identify potential nuclear substrates for GRK5. Nuclear extracts were prepared from HeLa cells and initially analyzed for GRKs as well as various cellular markers. The nuclear extract was highly enriched in the nuclear marker nucleolin and largely devoid of cytoplasmic (Hsp90) and membrane (Na+/K+ ATPase) markers (Fig. 1A). The nuclear fraction also contained endogenous GRK2 and GRK5 (Fig. 1A). To identify potential GRK substrates, the nuclear extract was chromatographed on an anion exchange column (Fig. 1B), and fractions were phosphorylated with or without the addition of purified GRK2 or GRK5. Although little phosphorylation was observed in most fractions, fraction 16 contained an ∼40-kDa protein that was phosphorylated by GRK5 (Fig. 1C, left panel) but not by GRK2 (Fig. 1C, right panel). The 40-kDa band was excised from the gel, proteolyzed with trypsin, and then analyzed by mass spectrometry. This analysis identified 21 unique peptides of which 12 were from nucleophosmin (NPM1), providing 18% overall sequence coverage (data not shown). Immunoblotting with an anti-NPM1 antibody confirmed that NPM1 is in fraction 16 as well as in the whole cell, cytosolic, and nuclear extracts (Fig. 1D). The nuclear extract also contained NPM1 oligomers of ∼200 kDa that have been previously reported (35).

FIGURE 1.

Identification of NPM1 as a GRK5 substrate. A, shown is characterization of the purity of the nuclear extract. Nucleolin is highly expressed in the nuclear extract, with minimal amounts of the cytosolic marker Hsp90, the plasma membrane marker Na+-K+ ATPase, or the ER marker calnexin. GRK2 and GRK5 are detected in the nuclear fractions using anti-GRK2 and GRK4–6 antibodies. T, total cell lysate; C, cytosolic fraction; N, nuclear extract. B, shown is a Coomassie-stained polyacrylamide gel of fractions 12–16 of a nuclear extract chromatographed on a Q-Sepharose column eluted with a linear gradient from 50 to 700 mm NaCl. An ∼40-kDa candidate nuclear protein in fraction 16 (eluting at ∼600 mm NaCl) is indicated by the arrow. C, shown is in vitro phosphorylation of fraction 16 by 200 nm GRK5 (left) or GRK2 (right) at 30 min (n = 3). D, shown is immunoblotting of fraction 16 with anti-NPM1 antibody. NPM1 in fraction 16 is comparable in size to that in cellular lysates.

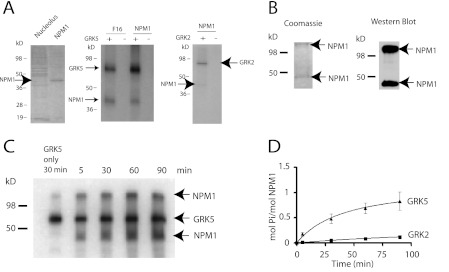

To verify that NPM1 is a substrate for GRK5, we purified NPM1 from HeLa cell nucleoli (Fig. 2A, left panel) and found that it was phosphorylated by GRK5 (Fig. 2A, center panel) but not by GRK2 (Fig. 2A, right panel). We also expressed and purified His-tagged NPM1 from E. coli (Fig. 2B) and found that it was phosphorylated by GRK5 to a stoichiometry of ∼1 mol of Pi/mol of NPM1 (Fig. 2, C and D). In contrast, NPM1 was only weakly phosphorylated by GRK2 (Fig. 2D). Thus, NPM1 appears to be a specific substrate for GRK5.

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of NPM1 phosphorylation by GRK5. A, shown is purified NPM1 from a nucleolar preparation of HeLa cells compared with a crude nucleolar preparation on a Coomassie-stained polyacrylamide gel (left panel). Phosphorylation of nucleolar-derived NPM1 by 200 nm GRK5 (center panel, compared with p40 phosphorylation) or 200 nm GRK2 (right panel), t = 30 min (n = 3) is shown. B, Coomassie staining of recombinant His-tagged NPM1 purified from E. coli (left panel) is shown. An immunoblot of purified NPM1 (right panel) is shown. Arrows indicate monomeric and oligomeric (∼200 kDa) forms of NPM1. C, shown is in vitro phosphorylation of 1 μm NPM1 by 200 nm GRK5 from 5 to 120 min. D, quantification of NPM1 phosphorylation by GRK2 and GRK5 (n = 4–5) is shown. The monomeric and oligomeric bands were excised and counted, and the data are combined to obtain the phosphorylation stoichiometry.

To determine whether endogenous NPM1 and GRK5 associate in cells, co-immunoprecipitation studies were performed using control and GRK5 shRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 3A). Endogenous GRK5 was found to co-immunoprecipitate with endogenous NPM1 from HeLa cells (Fig. 3B). The co-immunoprecipitation was largely lost in the GRK5 shRNA cells, whereas no GRK5 or NPM1 immunoprecipitation was observed when an identical mouse isotype IgG was used in place of anti-NPM1 (Fig. 3B). Similarly, endogenous NPM1 co-immunoprecipitated with GRK5, whereas reduced co- immunoprecipitation was observed in GRK5 shRNA cells or when a rabbit IgG was used in place of anti-GRK5 (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

NPM1 co-immunoprecipitates with GRK5 and their interaction is mediated by their respective N termini. A, shown is an immunoblot (IB) for GRK5 in HeLa cells stably transfected with control (C) or GRK5 (5) shRNA. B, detection of GRK5 in anti-NPM1 or anti-Ig2a immunoprecipitates (IP) derived from control or GRK5 shRNA-transfected cell lines is shown. This blot is representative of three-four experiments. C, shown is detection of NPM1 in anti-GRK5 or anti-IgG immunoprecipitates derived from either control or GRK5 shRNA cells. This blot is representative of 3–4 experiments. D, in vitro GST pulldown assays demonstrate the N terminus of NPM1 interacts with GRK5. Upper panel, NPM1 is divided into three domains: the N-terminal oligomerization domain (residues 1–119), the histone-binding domain (residues 119–190), and the DNA/RNA binding domain (residues 190–294). Lower panel, the GST-tagged NPM1 domain truncations were expressed in E. coli and purified using glutathione beads (Coomassie stain). 80 pmol of GST (∼25 kDa), GST-NPM1 (∼65 kDa), GST-NPM1(1–190) (∼45 kDa), GST-NPM1 (1–119) (∼37 kDa), GST-NPM1(1–102) (∼36 kDa), and GST-NPM1(1–15) (∼25 kDa) on glutathione beads were incubated with 10 pmol of purified GRK5 for 1 h at room temperature, washed extensively, and eluted with SDS sample buffer. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with the GRK4–6 antibody. Blots presented are representative of four experiments. E, GRK5 is subdivided into three domains: the N-terminal (1–180), catalytic (180–507), and C-terminal domain (507–590). GST (∼25 kDa), GST-GRK5(1–200) (∼45 kDa), and GST-GRK5-(489–562) (∼30 kDa) were expressed in E. coli and purified using glutathione beads (Coomassie stain). Eighty pmol of GST or GST-GRK5 truncations on glutathione beads were incubated with 10 pmol of purified NPM1 for 1 h at room temperature, washed extensively, and eluted with SDS sample buffer. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with anti-NPM1 antibodies. Blots presented are representative of four experiments.

To establish if NPM1 and GRK5 interact directly, GST pulldown experiments using purified proteins were performed. Purified GST-NPM1 was able to bind purified GRK5, demonstrating that these proteins can directly interact (Fig. 3D). Deletion mutagenesis was then used to define the region of NPM1 that interacts with GRK5. NPM1 is a 294-amino acid protein that contains domains involved in oligomerization (residues 1–119), histone binding (residues 119–190), and DNA/RNA binding (residues 190–294) (Fig. 3D) (33). A GST fusion protein containing the oligomerization domain was able to bind GRK5 as effectively as was full-length NPM1, whereas deletion of 17 residues from the C-terminal portion of this domain completely disrupted GRK5 binding (Fig. 3D). Thus, GRK5 primarily binds to the oligomerization domain of NPM1 with residues 103–119 appearing to play a major role in mediating this interaction. Similarly, a GST fusion protein containing the N-terminal domain of GRK5 (residues 1–200) was able to bind purified NPM1, whereas a fusion containing the C-terminal domain (residues 489–562) did not (Fig. 3E). The N-terminal region of GRK5 contains a short α-helical region that regulates receptor phosphorylation followed by a regulator of G protein signaling homology (RH) domain that likely mediates protein-protein interactions (42). These data demonstrate that GRK5 and NPM1 interact directly and suggest that the N-terminal RH domain of GRK5 interacts with the oligomerization domain of NPM1.

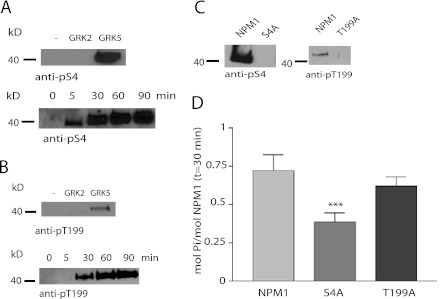

We next focused on identifying potential GRK5 phosphorylation sites on NPM1. Two well characterized phosphorylation sites on NPM1, Ser-4 and Thr-199, were initially explored using phospho-specific antibodies to determine whether these were potential sites for GRK5. NPM1 was incubated with GRK2 or GRK5 in vitro and then analyzed with anti-phospho-Ser-4 (Fig. 4A) and anti-phospho-Thr-199 (Fig. 4B) NPM1 antibodies. Both antibodies detected time-dependent phosphorylation of NPM1 by GRK5, and this was completely lost when Ser-4 or Thr-199 was mutated to alanine (Fig. 4C). In contrast, no NPM1 phosphorylation was observed with GRK2 (Fig. 4, A and B). To assess whether Ser-4 and Thr-199 were major sites of GRK5 phosphorylation, we evaluated phosphorylation of S4A and T199A mutants. Phosphorylation of NPM1-S4A by GRK5 was reduced by ∼50% compared with wild type NPM1, whereas phosphorylation of NPM1-T199A was reduced by only ∼15% (Fig. 4D). This suggests that Ser-4 is a primary phosphorylation site for GRK5, whereas Thr-199 may be a minor phosphorylation site.

FIGURE 4.

GRK5 phosphorylates NPM1 at Ser-4 and Thr-199 in vitro. A, phosphorylation of 1 μm NPM1 for 30 min by 50 nm GRK2 or GRK5 was detected by a NPM1-pS4 specific antibody (top panel) (n = 3). Time-dependent phosphorylation of 1 μm NPM1 for 0–90 min by 50 nm GRK5 was detected with the pS4 antibody (bottom panel) (n = 3). B, phosphorylation of 1 μm NPM1 for 30 min by 50 nm GRK2 or GRK5 was detected by a NPM1-Thr(P)-199-specific antibody (top panel) (n = 3). Time-dependent phosphorylation of NPM1 by 50 nm GRK5 for 0–90 min was detected with the Thr(P)-199 antibody (bottom panel) (n = 3). The dash denotes no protein kinase added. C, phosphorylation of 1 μm NPM1-S4A (left) or 1 μm NPM1-T199A (right) by 50 nm GRK5 for 30 min was detected using the respective phospho-antibodies compared with phosphorylation of 1 μm NPM1 (n = 3). D, in vitro phosphorylation of 1 μm NPM1, NPM1-S4A, and NPM1-T199A with 50 nm GRK5 for 30 min using radiolabeled ATP is shown. *** denotes p < 0.05, n = 4.

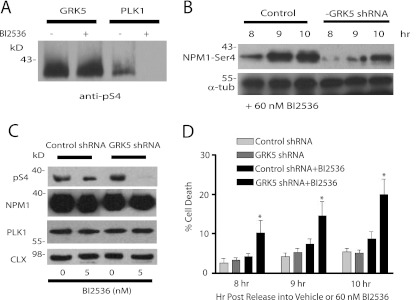

Because Ser-4 in NPM1 is phosphorylated by PLK1 in cells (43), we next evaluated any potential interplay between GRK5 and PLK1. To inhibit PLK1 activity, we used BI 2536, a high affinity PLK1 inhibitor with a Ki ∼ 0.5 nm (44). We initially tested whether BI 2536 had any effect on GRK5 activity. 60 nm BI 2536 completely inhibited PLK1 phosphorylation of NPM1 in vitro, whereas it had no effect on GRK5 phosphorylation of NPM1 (Fig. 5A). To determine whether GRK5 contributes to NPM1 phosphorylation in cells, we evaluated Ser-4 phosphorylation in control and GRK5 shRNA HeLa cells in the presence of PLK1 inhibition. Because NPM1 is normally phosphorylated during progression through the cell cycle, cells were initially synchronized by a double thymidine block and then released into media containing 60 nm BI 2536 for various times up to 10 h. Although 60 nm BI 2536 inhibited 90–95% of the Ser-4 phosphorylation (data not shown), some phosphorylation remained in the presence of PLK1 inhibition (Fig. 5B). This phosphorylation was most prominent at 8, 9, and 10 h post-thymidine release and was significantly attenuated in the GRK5 knockdown cells (Fig. 5B). We also evaluated Ser-4 phosphorylation after a 72-h treatment of asynchronous cells with a much lower concentration of BI 2536 (5 nm). Under these conditions, the inhibitor caused an ∼50% decrease in Ser-4 phosphorylation in control cells, whereas phosphorylation was completely lost in the GRK5 knockdown cells (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that GRK5 contributes to regulating the phosphorylation of Ser-4 in NPM1 in HeLa cells.

FIGURE 5.

GRK5 phosphorylates NPM1-Ser4 in HeLa cells. A, in vitro phosphorylation, detected by anti-pS4 NPM1 antibody, of purified 1 μm NPM1 with 50 nm GRK5 or 50 nm PLK1 in the presence or absence of 60 nm BI 2536 at t = 30 min is shown. The blot is representative of four experiments. B, shown is an immunoblot for phosphorylation of NPM1-S4 at 8, 9, and 10 h post-release in control or GRK5 shRNA stably transfected cells. α-Tubulin (α-tub) is blotted as a loading control. This blot is representative of three experiments. C, shown is immunoblotting for NPM1 phospho-Ser-4, NPM1, PLK1, and calnexin (CLX; loading control) in lysates of control or GRK5-shRNA stably transfected cells after 72 h of treatment with 5 nm BI 2536. Blots are representative of three experiments. D, shown is viability of cells, synchronized at G1/S by a double thymidine block then released into media with or without 60 nm BI 2536 at 8, 9, and 10 h post-release (the asterisk denotes p < 0.05, n = 4).

The phosphorylation of NPM1 on Ser-4 by PLK1 is important for proper mitotic assembly as cells transfected with NPM1-S4A display elongated and fragmented nuclei (43), similar to what is seen with PLK1 inhibition (45). Because PLK1 inhibition ultimately results in cell apoptosis (44, 45), we next tested whether GRK5 knockdown had any effect on cell death in the presence or absence of PLK1 inhibition. Although GRK5 knockdown or PLK1 inhibition alone did not significantly affect cell viability, the combination of PLK1 inhibition and GRK5 knockdown caused a dramatic increase in cell death at the 8-, 9-, and 10-h time points post-double thymidine release (Fig. 5D).

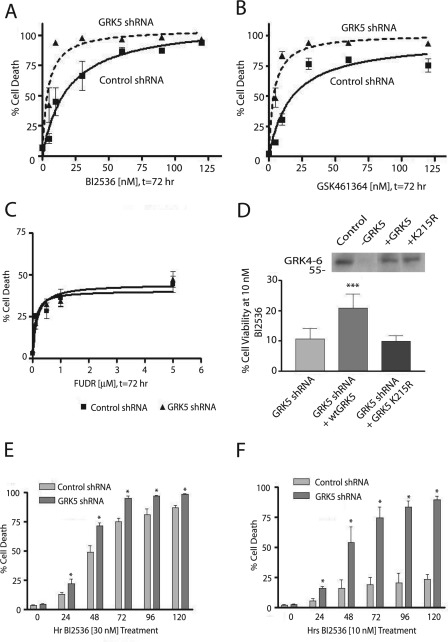

To determine whether GRK5 knockdown altered the sensitivity of cells to the effects of PLK1 inhibition, we measured cell death in control and GRK5 shRNA cells after a 72-h treatment with 0–120 nm BI 2536. In HeLa cells lacking GRK5, there was an ∼4.5-fold decrease in the EC50 of BI 2536-mediated cell death (control shRNA, 18.9 ± 5.2 nm; GRK5 shRNA, 4.1 ± 1.1 nm, n = 6, p < 0.05) (Fig. 6A). Similar results were observed in GRK5 siRNA-transfected cells (data not shown). To determine whether these effects were PLK1-specific, cells were incubated for 72 h with 0–120 nm GSK461364, a more selective PLK1 inhibitor (Fig. 6B). Similar to BI 2536, cells lacking GRK5 were ∼4.5-fold more sensitive to GSK461364 compared with control cells (EC50 for control shRNA cells, 17.0 ± 4.4 nm; EC50 for GRK5-shRNA cells, 3.8 ± 0.7 nm, n = 4, p < 0.05). To determine whether these results might involve a general effect attributed to GRK5 knockdown, we measured the sensitivity of cells to FUDR, which kills cells by inhibiting thymidylate synthetase. No differences were observed in the EC50 values associated with FUDR in control versus GRK5 shRNA lines (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Cells with decreased GRK5 expression are more sensitive to PLK1 inhibition. A, shown is cell death in control or GRK5-shRNA stably transfected cells after 72 h of treatment with 0–120 nm BI 2536 as determined by trypan blue exclusion (n = 6). B, shown is cell death in control or GRK5-shRNA stably transfected cells after 72 h treatment with 0–120 nm GSK461364, as determined by trypan blue exclusion (n = 4). C, shown is dose-response cell death in control or GRK5-shRNA stably transfected cells after 72 h of treatment with 0–5 μm FUDR as determined by trypan blue exclusion (n = 3). EC50 for control shRNA cells, 0.24 ± 0.1 μm; EC50 for GRK5-shRNA cells, 0.27 ± 0.08 nm, n = 3, p > 0.05. D, cell viability of GRK5-shRNA cells transfected with either pcDNA3 wild type GRK5 or catalytically inactive GRK5 (GRK5-K215R) and treated with 10 nm BI 2536, t = 72 h (n = 5), was determined by trypan blue exclusion. *** denotes p < 0.05 compared with vector-transfected control (n = 4). Inset, immunoblotting for GRK5 by GRK4–6 antibody in control or GRK5-shRNA stably transfected cell lines transfected with vector, wild type GRK5, or GRK5-K215R. The cell viability of control shRNA cells was ∼50–55% after the 72 h treatment with 10 nm BI 2536 (see Fig. 6A). E and F, cell death of control or GRK5 shRNA stably transfected cells treated with 30 nm (E) or 10 nm (F) BI 2536 (n = 3) for 0–120 h.

To further characterize the role of GRK5 in PLK1 inhibitor-induced cell death, we performed rescue experiments in the GRK5 shRNA HeLa cells by expressing RNAi-resistant mutants of wild type and catalytically inactive GRK5. These experiments demonstrate that reintroduction of wild type GRK5 into the GRK5 shRNA HeLa cells could partially rescue cell viability. Moreover, this rescue required the catalytic activity of GRK5 as no rescue was observed with the GRK5-K215R mutant (Fig. 6D). To determine the time course of cell death attributed to PLK1 inhibition, control and GRK5 shRNA cells were treated with either 10 or 30 nm BI 2536, and cell viability was quantified over a 120-h period. A significant increase in cell death was observed in the GRK5 shRNA cells at all time points examined at both the higher (Fig. 6E) and lower (Fig. 6F) doses of BI 2536. Collectively, these results suggest that GRK5 mediates resistance to PLK1 inhibition, possibly through its ability to phosphorylate Ser-4 in NPM1.

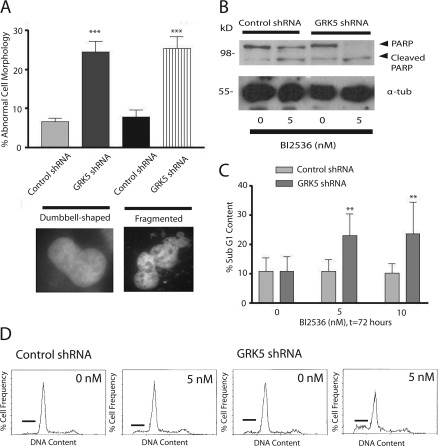

We next examined the morphology of control and GRK5 shRNA cells in the presence of PLK1 inhibition. Fluorescence microscopy of DAPI-stained cells was used to visualize aberrant nuclear morphology in cells treated with 5 nm BI 2536. These studies showed increased nuclei fragmentation and elongation in GRK5-shRNA cells compared with control HeLa cells (Fig. 7A). To test if the increased cell death with PLK1 inhibition and GRK5 knockdown was due to apoptosis, we measured the cleavage of PARP using an anti-PARP antibody. These studies revealed an increase in PARP cleavage in GRK5 shRNA cells treated with 5 nm BI 2536 compared with control cells treated with BI 2536 (Fig. 7B). PLK1-inhibited cells were also stained with propidium iodide, and their sub-G1 DNA content was examined by flow cytometry (Fig. 7, C and D). Increased sub-G1 DNA content suggests increased DNA fragmentation, which is another indicator for apoptosis. GRK5-shRNA cells had a significant increase in sub-G1 DNA content after a 72-h treatment with either 5 or 10 nm BI 2536 (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

Increased aberrant nuclear morphologies and apoptosis in GRK5-shRNA cells treated with low concentrations of BI 2536. A, shown is quantification of nuclei morphology, either dumbbell-like or fragmented, in control or GRK5 shRNA cells treated for 72 h with 5 nm BI 2536. *** denotes p < 0.05, n = 4–5 experiments with at least 70 cells counted per experiment. B, cleavage of PARP in control or GRK5 shRNA cells after 72 h treatment with 0 or 5 nm BI 2536 is shown. This blot is representative of four experiments. α-tub, tubulin. C, sub-G1 DNA content of control or GRK5 shRNA cells after 72 h treatment with 0, 5, or 10 nm BI 2536 is shown. ** denotes p < 0.05, n = 3. D, DNA content of control or GRK5 shRNA cells in the absence or presence of 5 nm BI 2536 for 72 h is shown. DNA content frequency histograms show control (left) or GRK5 (right) shRNA cells with or without 5 nm BI 2536 exposure for 72 h. These histograms are representative of three experiments. The bar indicates cell populations with sub-G1 DNA content.

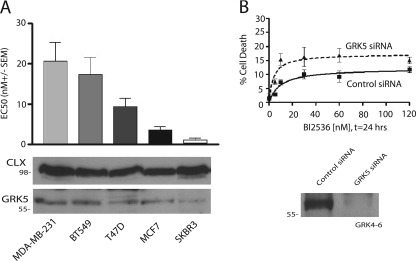

Because GRK5 levels may control the sensitivity of cells to PLK1 inhibition, we also tested if cell lines with higher GRK5 levels were more resistant to cell death associated with PLK1 inhibition. For these studies we chose a number of breast cancer cell lines. MDA-MB-231 and BT549 cells had higher GRK5 levels compared with T47D, SKBR3, and MCF7 cells with an ∼5-fold range in expression (Fig. 8A, lower panel). The sensitivity of these cells to BI 2536-mediated cell death mirrored the GRK5 expression level with MDA-MB-231 and BT549 being least sensitive and T47D, MCF7, and SKBR3 being most sensitive (Fig. 8A, upper panel). To further test if this effect was associated with GRK5 levels in MDA-MB-231 cells, GRK5 expression was decreased by siRNA transfection, and the sensitivity to BI 2536 was tested (Fig. 8B). GRK5 knockdown increased both the efficacy and potency of BI 2536 (control siRNA = 11.1 ± 3.3 nm; GRK5 siRNA = 4.2 ± 1.7 nm, n = 6), thus providing additional evidence that GRK5 modulates the sensitivity of cells to PLK1 inhibition.

FIGURE 8.

Breast cancer cell lines with higher GRK5 protein levels are less susceptible to PLK1 inhibition compared with those with lower GRK5 protein levels. A, expression levels of GRK5 by immunoblotting in different breast cancer cell lines are shown. Calnexin (CLX) is used as loading control. Top, different EC50s for the effect of BI 2536 in several cell lines are shown. EC50s were determined by measuring dose-response cell death after 72 h treatment with 0–120 nm BI 2536 by trypan blue exclusion. B, upper panel, cell death in control or GRK5 siRNA-transfected MDA-MB-231 cells after 24 h treatment with 0–120 nm BI 2536 was determined by trypan blue exclusion (n = 6). Lower panel, shown is expression of GRK5 in control siRNA or GRK5 siRNA treated cells.

DISCUSSION

In addition to their role in mediating the phosphorylation, desensitization, and trafficking of GPCRs, GRKs also phosphorylate and regulate the function of various non-receptor proteins (3). In this report we provide evidence that GRK5 phosphorylates the nuclear protein, NPM1. GRK5 directly interacts with NPM1, forming a complex through their N-terminal domains. GRK5 phosphorylates NPM1 at Ser-4 and Thr-199 in vitro, with Ser-4 serving as the major phosphorylation site. In cells, GRK5 phosphorylates NPM1 on Ser-4, a site that is also phosphorylated by PLK1 (43). Interestingly, GRK5 phosphorylation of NPM1 may confer resistance to cell death mediated by PLK1 inhibition. Cell lines with higher GRK5 levels show increased resistance to PLK1 inhibition, whereas cells with lower GRK5 levels are more sensitive to undergoing cell death.

NPM1 is a multifunctional protein involved in a wide variety of different cellular activities with many of them controlled by phosphorylation (33, 34). Phosphorylation of NPM1 at Ser-4 by PLK1 is involved in mitotic spindle formation (43), and overexpression of a NPM1-S4A mutant leads to cytokinetic defects (43) perhaps leading to cell death (45). Phosphorylation at Thr-199 by cyclin-dependent kinase 1 is involved in regulating the centrosome (33), whereas the phosphorylation of both Ser-4 and Thr-199 controls centrosome duplication (33, 46). Interestingly, GRK5 is also localized in the centrosome, although it does not appear to regulate centrosomal duplication (16). Nevertheless, knockdown of GRK5 leads to increased apoptosis associated with PLK1 inhibition, suggesting interplay between GRK5 and PLK1 in regulating the phosphorylation of NPM1 and controlling normal cell function.

Our results demonstrate that GRK5 phosphorylates NPM1 on Ser-4 both in vitro and in cells and likely coordinates with PLK1 in this process. Considering that PLK1 inhibition leads to cell death (44, 45), GRK5 might function to maintain particular PLK1-linked cell division processes associated with NPM1 function. During cell division, NPM1 is involved in spindle and centrosome formation as well as kinetochore-microtubule attachments (47). As a result, a certain level of active NPM1 could prevent spindle collapse associated with PLK1 inhibition (48) and thus help maintain cell viability. Decreasing GRK5 levels increased BI 2536-mediated cell death most likely because GRK5 no longer compensates for loss of PLK1 activity in phosphorylating NPM1, leading to increased nuclear elongation and fragmentation. These defects ultimately lead to increased apoptosis.

The ability of GRK5 to compensate for PLK1 activity is an interesting example of protein kinases that have overlapping substrate specificities. The function of GRK5 in phosphorylating NPM1 may be important as PLK1 is a therapeutic target in the treatment of a number of cancers, including esophageal cancer (49), neuroblastomas (50), and others (51). Reducing the GRK5 level and/or activity in cancer cells, because of its potential ability to compensate for PLK1 activity at NPM1, could enhance the potency of PLK1 inhibitors in mediating cancer cell death. This has been demonstrated here with decreasing GRK5 levels in MDA-MB-231 cells. With lowered GRK5 levels, lower levels of PLK1 inhibitor could be administered to treat certain cancers, potentially avoiding off-target effects such as neutropenia, which has limited the effectiveness of these drugs in some clinical trials (51). Furthermore, PLK1 inhibitors might prove more effective in treating tumors that have low GRK5 expression, thereby enabling the use of lower inhibitor concentrations and avoiding off-target effects.

Interestingly, GRK5 has recently been implicated in the development of prostate cancer (25). GRK5 also appears to have a role in cardiovascular disease as a GRK5-Q41L polymorphism that is prevalent in African Americans is protective in the development of heart failure (52). Moreover, GRK5 attenuates atherosclerosis in mice through multiple mechanisms including reduced NF-κB activity and desensitization of various GPCRs and growth factor receptors (53). Additional mouse knock-out and transgenic studies reveal that GRK5 has many additional physiological roles (54). These include roles in regulating muscarinic receptor function (55), neuronal morphogenesis (56), and possibly the development of Alzheimer disease (26). GRK5 also phosphorylates and regulates histone deacetylase 5 in the nucleus (13) and appears to regulate apoptosis (15) and cell cycle progression (16) through p53 phosphorylation. Although we do not know if GRK5 regulation of NPM1 contributes to any of these observed phenotypes in mice or humans, it is evident that GRK5 has many important physiological and pathophysiological roles.

GRK5-NPM1 complexes could suggest novel means by which GPCRs may regulate processes associated with NPM1. NPM1 itself has been demonstrated to interact and affect the activity of CXCR4 (37). This receptor could be an important modulator of NPM1 function as it has been reported to be localized in perinuclear regions in metastatic renal carcinoma (58). NPM1 has also been reported to interact with the GPCR adaptor proteins, arrestins (59). Because GRKs are activated by GPCR binding (57), GPCR activation might be able to regulate the phosphorylation state of NPM1.

In summary, we demonstrate NPM1 as a substrate for GRK5. GRK5-mediated phosphorylation of NPM1-Ser-4 leads to an increased resistance to PLK1 inhibitors, which could potentially reduce the effectiveness of these inhibitors to mediate cancer cell death. Therefore, this study both illustrates the increasing complexity of the GRK kinome and suggests that the protein composition of cancer cells needs to be considered as levels of other proteins acting at similar sites of action could affect chemotherapeutic outcomes.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM44944 and CA129626 (to J. L. B.).

- GRK

- G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) kinase

- FUDR

- 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine

- NPM1

- nucleophosmin

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PLK1

- polo-like kinase 1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Krupnick J. G., Benovic J. L. (1998) The role of receptor kinases and arrestins in G protein-coupled receptor regulation. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 38, 289–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moore C. A., Milano S. K., Benovic J. L. (2007) Regulation of receptor trafficking by GRKs and arrestins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 69, 451–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gurevich E. V., Tesmer J. J., Mushegian A., Gurevich V. V. (2012) G protein-coupled receptor kinases: more than just kinases and not only for GPCRs. Pharmacol. Ther. 133, 40–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pitcher J. A., Hall R. A., Daaka Y., Zhang J., Ferguson S. S., Hester S., Miller S., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J., Barak L. S. (1998) The G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 is a microtubule-associated protein kinase that phosphorylates tubulin. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12316-12324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carman C. V., Som T., Kim C. M., Benovic J. L. (1998) Binding and phosphorylation of tubulin by G protein-coupled receptor kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 20308–20316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pronin A. N., Morris A. J., Surguchov A., Benovic J. L. (2000) Synucleins are a novel class of substrates for G protein-coupled receptor kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 26515–26522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ruiz-Gómez A., Humrich J., Murga C., Quitterer U., Lohse M. J., Mayor F., Jr. (2000) Phosphorylation of phosducin and phosducin-like protein by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29724–29730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ruiz-Gomez A., Mellström B., Tornero D., Morato E., Savignac M., Holguín H., Aurrekoetxea K., González P., González-García C., Ceña V., Mayor F., Jr., Naranjo J. R. (2007) G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2-mediated phosphorylation of Downstream Regulatory Element Antagonist Modulator regulates membrane trafficking of Kv4.2 potassium channel. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 1205–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peregrin S., Jurado-Pueyo M., Campos P. M., Sanz-Moreno V., Ruiz-Gomez A., Crespo P., Mayor F., Jr., Murga C. (2006) Phosphorylation of p38 by GRK2 at the docking groove unveils a novel mechanism for inactivating p38MAPK. Curr. Biol. 16, 2042–2047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patial S., Luo J., Porter K. J., Benovic J. L., Parameswaran N. (2010) G-protein coupled receptor kinases mediate TNFα-induced NFκB signaling via direct interaction with and phosphorylation of IκBα. Biochem. J. 425, 169–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Parameswaran N., Pao C. S., Leonhard K. S., Kang D. S., Kratz M., Ley S. C., Benovic J. L. (2006) Arrestin-2 and G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 interact with NFκB1 p105 and negatively regulate lipopolysaccharide-stimulated ERK1/2 activation in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34159–34170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cant S. H., Pitcher J. A. (2005) G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2-mediated phosphorylation of ezrin is required for G protein-coupled receptor-dependent reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3088–3099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martini J. S., Raake P., Vinge L. E., DeGeorge B. R., Jr., DeGeorge B., Jr., Chuprun J. K., Harris D. M., Gao E., Eckhart A. D., Pitcher J. A., Koch W. J. (2008) Uncovering G protein-coupled receptor kinase-5 as a histone deacetylase kinase in the nucleus of cardiomyocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12457–12462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barthet G., Carrat G., Cassier E., Barker B., Gaven F., Pillot M., Framery B., Pellissier L. P., Augier J., Kang D. S., Claeysen S., Reiter E., Banères J. L., Benovic J. L., Marin P., Bockaert J., Dumuis A. (2009) β-Arrestin1 phosphorylation by GRK5 regulates G protein-independent 5-HT4 Receptor Signaling. EMBO J. 28, 2706–2718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen X., Zhu H., Yuan M., Fu J., Zhou Y., Ma L. (2010) G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 phosphorylates p53 and inhibits DNA damage-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12823–12830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Michal A. M., So C. H., Beeharry N., Shankar H., Mashayekhi R., Yen T. J., Benovic J. L. (2012) G protein-coupled-receptor kinase 5 is localized to centrosomes and regulates cell cycle progression. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 6928–6940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barker B. L., Benovic J. L. (2011) G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 phosphorylation of Hip regulates internalization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. Biochemistry 50, 6933–6941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ungerer M., Böhm M., Elce J. S., Erdmann E., Lohse M. J. (1993) Altered expression of β-adrenergic receptor kinase and β1-adrenergic receptors in the failing human heart. Circulation 87, 454–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gros R., Benovic J. L., Tan C. M., Feldman R. D. (1997) G protein-coupled receptor kinase activity is increased in hypertension. A potential explanation for impaired β-adrenergic responsiveness. J. Clin. Invest. 99, 2087–2093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Felder R. A., Sanada H., Xu J., Yu P. Y., Wang Z., Watanabe H., Asico L. D., Wang W., Zheng S., Yamaguchi I., Williams S. M., Gainer J., Brown N. J., Hazen-Martin D., Wong L. J., Robillard J. E., Carey R. M., Eisner G. M., Jose P. A. (2002) G protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 gene variants in human essential hypertension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 3872–3877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang Z. M., Gold J. I., Koch W. J. (2012) G protein-coupled receptor kinases in normal and failing myocardium. Front. Biosci. 17, 3047–3060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matsubayashi J., Takanashi M., Oikawa K., Fujita K., Tanaka M., Xu M., De Blasi A., Bouvier M., Kinoshita M., Kuroda M., Mukai K. (2008) Expression of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 is associated with breast cancer tumorigenesis. J. Pathol. 216, 317–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tiedemann R. E., Zhu Y. X., Schmidt J., Yin H., Shi C. X., Que Q., Basu G., Azorsa D., Perkins L. M., Braggio E., Fonseca R., Bergsagel P. L., Mousses S., Stewart A. K. (2010) Kinome-wide RNAi studies in human multiple myeloma identify vulnerable kinase targets, including a lymphoid-restricted kinase, GRK6. Blood 115, 1594–1604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Woerner B. M., Luo J., Brown K. R., Jackson E., Dahiya S. M., Mischel P., Benovic J. L., Piwnica-Worms D., Rubin J. B. (2012) Suppression of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 3 expression is a feature of classical GBM that is required for maximal growth. Mol. Cancer Res. 10, 156–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim J. I., Chakraborty P., Wang Z., Daaka Y. (2012) G-protein coupled receptor kinase 5 regulates prostate tumor growth. J. Urol. 187, 322–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Suo Z., Cox A. A., Bartelli N., Rasul I., Festoff B. W., Premont R. T., Arendash G. W. (2007) GRK5 deficiency leads to early Alzheimer-like pathology and working memory impairment. Neurobiol. Aging 28, 1873–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bychkov E. R., Gurevich V. V., Joyce J. N., Benovic J. L., Gurevich E. V. (2008) Arrestins and two receptor kinases are up-regulated in Parkinson disease with dementia. Neurobiol. Aging 29, 379–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. García-Sevilla J. A., Alvaro-Bartolomé M., Díez-Alarcia R., Ramos-Miguel A., Puigdemont D., Pérez V., Alvarez E., Meana J. J. (2010) Reduced platelet G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 in major depressive disorder. Antidepressant treatment-induced up-regulation of GRK2 protein discriminates between responder and non-responder patients. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 20, 721–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bychkov E. R., Ahmed M. R., Gurevich V. V., Benovic J. L., Gurevich E. V. (2011) Reduced expression of G protein-coupled receptor kinases in schizophrenia but not in schizoaffective disorder. Neurobiol. Dis. 44, 248–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johnson L. R., Scott M. G., Pitcher J. A. (2004) G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 contains a DNA binding nuclear localization sequence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 10169–10179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jiang X., Benovic J. L., Wedegaertner P. B. (2007) Plasma membrane and nuclear localization of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 6A. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 2960–2969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Frehlick L. J., Eirín-López J. M., Ausió J. (2007) New insights into the nucleophosmin/nucleoplasmin family of nuclear chaperones. Bioessays 29, 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Okuwaki M. (2008) The structure and functions of NPM1/nucleophosmin/B23, a multifunctional nucleolar acidic protein. J. Biochem. 143, 441–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Grisendi S., Mecucci C., Falini B., Pandolfi P. P. (2006) Nucleophosmin and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chan P. K., Chan F. Y. (1995) Nucleophosmin/B23 (NPM) oligomer is a major and stable entity in HeLa cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1262, 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pronin A. N., Carman C. V., Benovic J. L. (1998) Structure-function analysis of G protein-coupled receptor kinase-5. Role of the carboxyl terminus in kinase regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31510–31518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang W., Navenot J. M., Frilot N. M., Fujii N., Peiper S. C. (2007) Association of nucleophosmin negatively regulates CXCR4-mediated G protein activation and chemotaxis. Mol. Pharmacol. 72, 1310–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kang D. S., Kern R. C., Puthenveedu M. A., von Zastrow M., Williams J. C., Benovic J. L. (2009) Structure of an arrestin2-clathrin complex reveals a novel clathrin binding domain that modulates receptor trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 29860–29872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carey M. F., Peterson C. L., Smale S. T. (2009) Dignam and Roeder nuclear extract preparation. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009(12):pdb.prot5330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kunapuli P., Onorato J. J., Hosey M. M., Benovic J. L. (1994) Expression, purification, and characterization of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase GRK5. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 1099–1105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim C. M., Dion S. B., Onorato J. J., Benovic J. L. (1993) Expression and characterization of two β-adrenergic receptor kinase isoforms using the baculovirus expression system. Receptor 3, 39–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Noble B., Kallal L. A., Pausch M. H., Benovic J. L. (2003) Development of a yeast bioassay to characterize G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Identification of an N-terminal region essential for receptor phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47466–47476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang H., Shi X., Paddon H., Hampong M., Dai W., Pelech S. (2004) B23/nucleophosmin serine 4 phosphorylation mediates mitotic functions of polo-like kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35726–35734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Steegmaier M., Hoffmann M., Baum A., Lénárt P., Petronczki M., Krssák M., Gürtler U., Garin-Chesa P., Lieb S., Quant J., Grauert M., Adolf G. R., Kraut N., Peters J. M., Rettig W. J. (2007) BI 2536, a potent and selective inhibitor of polo-like kinase 1, inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Curr. Biol. 17, 316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu X., Erikson R. L. (2003) Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) depletion induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 5789–5794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Krause A., Hoffmann I. (2010) Polo-like kinase 2-dependent phosphorylation of NPM/B23 on serine 4 triggers centriole duplication. PLoS One 5, e9849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Amin M. A., Matsunaga S., Uchiyama S., Fukui K. (2008) Nucleophosmin is required for chromosome congression, proper mitotic spindle formation, and kinetochore-microtubule attachment in HeLa cells. FEBS Lett. 582, 3839–3844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lénárt P., Petronczki M., Steegmaier M., Di Fiore B., Lipp J. J., Hoffmann M., Rettig W. J., Kraut N., Peters J. M. (2007) The small-molecule inhibitor BI 2536 reveals novel insights into mitotic roles of polo-like kinase 1. Curr. Biol. 17, 304–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ito T., Sato F., Kan T., Cheng Y., David S., Agarwal R., Paun B. C., Jin Z., Olaru A. V., Hamilton J. P., Selaru F. M., Yang J., Matsumura N., Shimizu K., Abraham J. M., Shimada Y., Mori Y., Meltzer S. J. (2011) Polo-like kinase 1 regulates cell proliferation and is targeted by miR-593 in esophageal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 129, 2134–2146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ackermann S., Goeser F., Schulte J. H., Schramm A., Ehemann V., Hero B., Eggert A., Berthold F., Fischer M. (2011) Polo-like kinase 1 is a therapeutic target in high-risk neuroblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 731–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lens S. M., Voest E. E., Medema R. H. (2010) Shared and separate functions of polo-like kinases and aurora kinases in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 825–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liggett S. B., Cresci S., Kelly R. J., Syed F. M., Matkovich S. J., Hahn H. S., Diwan A., Martini J. S., Sparks L., Parekh R. R., Spertus J. A., Koch W. J., Kardia S. L., Dorn G. W., 2nd (2008) A GRK5 polymorphism that inhibits β-adrenergic receptor signaling is protective in heart failure. Nat. Med. 14, 510–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wu J. H., Zhang L., Fanaroff A. C., Cai X., Sharma K. C., Brian L., Exum S. T., Shenoy S. K., Peppel K., Freedman N. J. (2012) G protein-coupled receptor kinase-5 attenuates atherosclerosis by regulating receptor tyrosine kinases and 7-transmembrane receptors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 308–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Premont R. T., Gainetdinov R. R. (2007) Physiological roles of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 69, 511–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gainetdinov R. R., Bohn L. M., Walker J. K., Laporte S. A., Macrae A. D., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J., Premont R. T. (1999) Muscarinic supersensitivity and impaired receptor desensitization in G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5-deficient mice. Neuron 24, 1029–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen Y., Wang F., Long H., Chen Y., Wu Z., Ma L. (2011) GRK5 promotes F-actin bundling and targets bundles to membrane structures to control neuronal morphogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 194, 905–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chen C. Y., Dion S. B., Kim C. M., Benovic J. L. (1993) β-adrenergic receptor kinase. Agonist-dependent receptor binding promotes kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 7825–7831 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang L., Wang Z., Yang B., Yang Q., Wang L., Sun Y. (2009) CXCR4 nuclear localization follows binding of its ligand SDF-1 and occurs in metastatic but not primary renal cell carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 22, 1333–1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Xiao K., McClatchy D. B., Shukla A. K., Zhao Y., Chen M., Shenoy S. K., Yates J. R., 3rd, Lefkowitz R. J. (2007) Functional specialization of β-arrestin interactions revealed by proteomic analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 12011–12016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]