Abstract

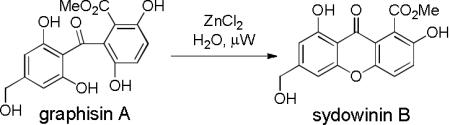

Efficient syntheses of the highly substituted benzophenone graphisin A and the xanthone sydowinin B are described. Key steps involve aryl anion addition to substituted benzaldehyde derivatives, subsequent methyl ester installation, and dehydrative cyclization. Oxidation of graphisin A led to a spirodienone derived from a highly substituted benzoquinone intermediate.

Acremoxanthone A2 (1), xanthoquinodin A3 (2), and acremonidin A (3)4 (Figure 1) are members of a class of heterodimeric natural products originally isolated from Acremonium sp. BCC31806, Humicola sp. FO888 and Acremonium sp., LL-Cyan 416, respectively. These natural products share structurally related anthraquinone and xanthone-derived monomer units which are linked by a unique bicyclo[3.2.2] ring system.5 We have initiated synthetic studies toward these targets with syntheses of the requisite xanthone and benzophenone fragments present in the natural product frameworks. In our initial studies, we have targeted the highly functionalized, tetra-ortho-substituted benzophenone graphisin A6 (4) and the corresponding cyclized xanthone sydowinin B7 (5). Herein, we report the total synthesis of the highly substituted benzophenone8 graphisin A using a suitably functionalized benzophenone as well as preparation of the derived xanthone sydowinin B via dehydrative cyclization.

Figure 1.

Acremoxanthone A and related natural products

Our initial plan (Figure 2) was to prepare benzophenone nitrile 6 via aryl anion addition to a substituted benzaldehyde according to literature precedent.9 We envisioned that acidic methanolysis10 of aryl nitrile 6 followed by global deprotection should provide graphisin A (4). Sydowinin B (5) could then be accessed through dehydrative cyclization.11

Figure 2.

Initial synthetic plan

In our forward synthesis, benzaldehyde 7 was regioselectively brominated and protected as a bis-MOM ether in 82% yield over two steps (Scheme 1). Regioselective deprotonation of 8 with n-BuLi, followed by addition of aldehyde 9 at 0 °C, provided benzylic alcohol 10 in 56% yield with the remainder of the mass balance consisting of byproducts derived from competitive lithium-halogen exchange of the ortho aryl bromide. Oxidation of 10 with 2-iodoxybenzoic acid (IBX) provided bromobenzophenone 11 (75%). We had initially planned to utilize 11 directly in palladium-catalyzed carbonylative methyl ester formation (Pd(dppf)Cl2, CO, NEt3, DMF/MeOH);12 however, this substrate was found to be unreactive likely due to the highly electron rich and bis-ortho-substituted aryl ring. Efforts to install the methyl ester on either bromobenzaldehyde 9 or its corresponding acetal-protected derivatives were also unsuccessful. Similarly, anion chemistry (e.g. lithium halogen exchange, Grignard formation) of aryl bromide substrates was also found to be unproductive.8c However, compound 11 was found to undergo smooth cyanation using Pd(PPh3)4 and Zn(CN)2 under microwave heating to afford aryl nitrile 6 in 60% yield.13

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of aryl nitrile 6

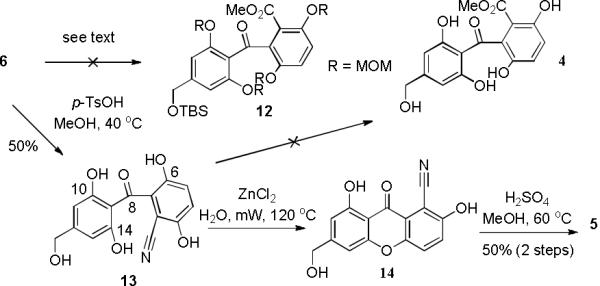

Initial attempted hydrolysis of aryl nitrile 6 to the derived acid or ester 12 (aq NaOH or H2SO4) resulted in either decomposition or partial MOM deprotection (Scheme 2). Attempted partial hydrolysis of the primary amide with K2CO3 and H2O214 resulted in no reaction. Similarly, treatment of 6 with methyl triflate in CH2Cl2 followed by a methanolysis to access the imidate in a Ritter-type reaction was also unsuccessful.15 Attempts to hydrolyze the nitrile in the presence of methanol (BF3,16 FeCl3,17 TMSCl,18 and H2SO419) resulted in mixtures of partially and fully MOM-deprotected compounds with the aryl nitrile remaining intact.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of sydowinin B via an aryl nitrile

In light of the apparent incompatibility of the MOM protecting groups with nitrile hydrolysis conditions, we elected to fully deprotect benzophenone 6 to tetraphenol 13 prior to hydrolysis (Scheme 2). Accordingly, treatment of nitrile 6 with p-TsOH in MeOH at 40 °C produced a deep red solution whereby the protecting groups were globally removed to afford benzophenone 13 in 50% yield. Purification of polyphenol 13 on silica gel was found to be difficult due its high polarity and propensity to form an intractable, red-colored salt with residual p-TsOH. An example of a highly substituted benzophenone nitrile hydrolysis has been reported.20 However, standard acidic hydrolysis9 (H2SO4 or HCl, MeOH, 60 °C) of 13 resulted in recovered starting material and minor formation of xanthone 14, whereas standard basic conditions21 (NaOH) resulted in decomposition.

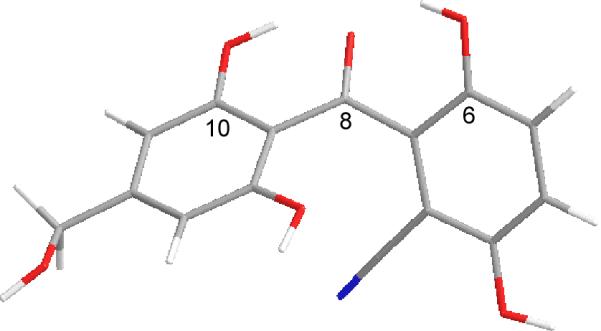

At this juncture, we elected to optimize the xanthone formation / nitrile methanolysis sequence. We observed dehydrative cyclization to the xanthone when attempting to hydrolyze nitrile 13 with DOWEX-50 resin in water under microwave heating.22 We later observed clean conversion of 13 to xanthone 14 using microwave heating with aqueous ZnCl2.23 A ground state model of nitrile 13 (Figure 3) shows that the benzophenone exists substantially in a bisected conformation with hydrogen bonding maintained between the C-6 and C-10 phenols and the C-8 ketone. However, internal hydrogen-bonding of the phenols may be disrupted in water such that rotation can occur prior to cyclization to form xanthone 14. Xanthone 14 was finally subjected to acidic methanolysis conditions (3M H2SO4, MeOH, 60 °C) which afforded sydowinin B (5) in 50% yield (two steps).

Figure 3.

DFT minimized model of nitrile 13

To enable installation of the requisite methyl ester and access graphisin A (4) without dehydrative cyclization, we implemented the alternative route shown in Scheme 3. Bromoaldehyde249 was reduced and benzyl-protected to afford aryl bromide 15 in 80% yield (two steps). Regioselective deprotonation of 8 and subsequent quenching with DMF provided benzaldehyde 16 (78%). Lithium halogen exchange of aryl bromide 15 at −78 °C in ether with t-BuLi followed by a rapid quench with aldehyde 16 provided benzyl alcohol 17 (61%). Subsequent IBX oxidation afforded ketone 18 in 78% yield (Scheme 4). Initial attempted conditions for selective benzyl deprotection of 18 (H2, Pd(OH)2, MeOH) resulted in complete conversion to the over-reduced product 19, analogous to a product25 reported by Snider and coworkers for a similar substrate.26 However, hydrogenolysis of 18 using Pd/C in THF/MeOH (3:1) led to the desired hydroxybenzophenone 20 (Scheme 5). It is apparent that sole use of a polar protic solvent activates 20 toward hemiketal formation which undergoes further hydrogenolysis to the corresponding dihydroisobenzofuran 19.

Scheme 3.

Alternative route to graphisin A

Scheme 4.

Dihydroisobenzofuran formation

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of sydowinin B via graphisin A

A three-step oxidation-methylation sequence was next conducted on the protected benzophenone 20 involving sequential Dess-Martin and Pinnick oxidations followed by treatment with excess TMSCH2N2 in 1:1 MeOH/Et2O to provide methyl ester 12 in 65% yield over 3 steps (Scheme 5).25 Compound 12 was fully deprotected with p-TsOH in MeOH to provide graphisin A (4) in 77% yield. Analytical data for 4 including 1H and 13C NMR spectra were in agreement with those reported for the natural product.6 Graphisin A (4) could also be converted to sydowinin B (5) in 58% yield by dehydrative cyclization with aqueous ZnCl2 under microwave conditions (120 °C).23

It has been proposed that the biosynthesis of various members of the blennolide/secalonic acid27 family of natural products proceeds through oxidation/reduction of functionalized benzophenone intermediates resembling graphisin A.28 Accordingly, we conducted preliminary investigations as to whether graphisin A (4) could be converted to dienone 22 via oxidation to benzoquinone 21 followed by oxa-Michael addition (Scheme 6).29 Treatment of graphisin A (4) with phenyliodine diacetate (PIDA) resulted in clean oxidative cyclization to spirodienone 23.30 Oxidations of hydroxybenzophenones to similar spiro-dienones are known25,31and are thought to occur via a phenoxide radical that is aligned to favor the 5-memberd ring due to a bisected conformation of the highly substituted benzophenone. Spirodienone 23 was treated under acidic conditions25 to provide a mixture of rearranged acid 24 (57%) and depsidone 25 (12%). Acid 24 could be further cyclized to depsidone 25 by heating with TFAA in toluene (68%). In a similar fashion, oxidation of 4 with FeCl3 provided a mixture of 24 (39%) and 25 (44%) as the sole products.

Scheme 6.

Oxidation of graphisin A

Following reported dehydrogenation conditions that likely proceed through quinone intermediates,32 treatment of graphisin A (4) with Pd/C-O2 also provided spirodienone 23 in 89% yield. This result supports the intermediacy of benzoquinone 21 enroute to 23. While both 6-endo-trig and 5-exo-trig cyclization modes of 21 are possible,33 the observed isomer 23 is likely favored due to the bisected conformation34 of proposed intermediate 21 which places one ortho-phenol in favorable alignment with the π*-orbital of the C-7 quinone carbon (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

DFT minimized model of proposed benzoquinone intermediate 21

In conclusion, an efficient synthesis of graphisin A has been accomplished employing aryl anion addition to a benzaldehyde, followed by oxidation to a highly substituted benzophenone, subsequent methyl ester installation, and global deprotection. Graphisin A was further converted by dehydrative cyclization under microwave conditions to the xanthone sydowinin B. Oxidation of graphisin A led to formation of a spirodienone likely from a highly substituted and bisected benzoquinone intermediate. Further studies employing graphisin A and sydowinin B toward the synthesis of acremoxanthones and related natural products are currently in progress and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Financial support from the National Institute of Health (RO1 CA137270 and CA 099920) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Prof. P. Pittayakhajonwut, Bioresources Research Laboratory, Thailand for providing a sample of natural graphisin A and Tian Qin (Boston University) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Detailed experimental procedures and spectral data for all compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Presented in part at the 240th American Chemical Society National Meeting; Boston. Aug 22-26, 2010; abstract ORGN 410. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Isaka M, Palasarn S, Auncharoen P, Komwijit S, Jones EB. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;50:284–287. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Tabata N, Tomoda H, Matsuzaki K, Omura S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:8558–8564. [Google Scholar]

- (4).He H, Bigelis R, Solum E, Carter G. J. Antibiot. 2003;56:923–930. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.56.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Milat ML, Praange T, Ducrot PH, Tabet JC, Einhorn J, Blein JP, Lallelmand JY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:1478–1479. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jalal MA, Hossain MB, Robeson DJ, Helm D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:5967–5971. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Pittayakhajonwut P, Sri-indrasutdhi V, Dramae A, Lapanun S, Suvannakad R, Tantichareon M. Aust. J. Chem. 2009;62:389–391. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Hamasaki T, Sato Y, Hatsuda Y. Agr. Biol. Chem. 1975;39:2341–2345. [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Nicolaou KC, Bunnage ME, Koide K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:8402–8403. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kaiser F, Schwink L, Velder J, Schmalz HG. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:9248–9256. doi: 10.1021/jo026232t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Slavov N, Cvengros J, Neudorfl JM, Schmalz HG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:7588–7591. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For syntheses of highly substituted benzophenones, see:

- (9).Hollinshead SP, Nichols JB, Wilson JW. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:6703–6709. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Clarke HT, Taylor ER. Org. Synth. Collect. 1943;2:588. [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) Jeso V, Nicolaou KC. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1161–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.12.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sousa ME, Pinto MM. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005;12:2447–2479. doi: 10.2174/092986705774370736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Diderot NT, Silvere N, Etienne T. Adv. Phytomed. 2006;2:273–298. [Google Scholar]; (d) Pinto MMM, Castanheiro RAP. Natural Prod. 2009:520–675. [Google Scholar]; For recent reviews of xanthone syntheses, see:

- (12).Brennfuhrer A, Neumann H, Beller M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:4114–4133. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tschaen DM, Desmond R, King AO, Fortin MC, Pipik B, King S, Verhoeven TR. Synth. Commun. 1994;24:887–890. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Katritzky AR, Pilarski B, Urogdi L. Synthesis. 1989;12:949–950. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Booth BL, Jibodu KO, Proenca MF. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1. 1983:1067–1068. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Jayachitra G, Yasmeen N, Srinivasa K, Ralte SL, Singh AK. Synth. Commun. 2003;33:3461–3466. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Srinivasan R, Rao KS, Jayachitra G, Ralte SL. Synthetic Commun. 2006;36:2883–2886. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Luo FT, Jeevanadam A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:9455–9456. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Anzalone L, Hirsch JA. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:2128–2133. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Storm JP, Andersson CM. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:5264–5274. doi: 10.1021/jo000421z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Staab HA, Hauck R, Popp B. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1998;1:631–642. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lindstrom U. Green Chem. 2006;8:22–24. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Manjula K, Pasha MA. Synth. Commun. 2007;37:1545–1550. [Google Scholar]; For Zn (II)-mediated dehydration of amides in water, see:

- (24).Goddard ML, Tabacchi R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:909–911. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Yu M, Snider BB. Org. Lett. 2011;13:4224–4227. doi: 10.1021/ol201561w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).We observed aryl and MOM ether peak broadening in the 1H and 13C NMR spectra for compound 19 similar to a 2,6-disubstituted aryl dihydroisobenzofuran reported in reference 25 (see Supporting Information for details).

- (27).(a) Zhang W, Krohn K, Flörke U, Pescitelli G, Di Bari L, Antus S, Kurtan T, Rheinheimer J, Draeger S, Schulz B. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:4913–4923. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gerard EMC, Bräse S. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:8086–8089. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Qin T, Johnson RP, Porco JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1714–1717. doi: 10.1021/ja110698n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).(a) Kurobane I, Vining LC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;16:1379–1382. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kurobane I, Vining LC, McInnes AC. J. Antibio. 1979:1256–1266. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.32.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bräse S, Encinas A, Keck J, Nising CF. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:3903–3990. doi: 10.1021/cr050001f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).(a) Franck B, Stockigt U, Franckowiak G. Chem. Ber. 1973;106:1198–1220. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC, Li A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;120:6681–6684. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bröhmer MC, Bourcet E, Nieger M, Bräse S. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:13706–13711. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tisdale EJ, Kochman DA, Theodorakis EA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:3281–3284. [Google Scholar]; (e) Suzuki Y, Fukuta Y, Ota S, Kamiya M, Sato M. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:3960–3967. doi: 10.1021/jo200303c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For intramolecular oxa-Michael reactions to form tetrahydroxanthones, see:; For xanthone formation, see:

- (30).See Supporting Information for details on characterization.

- (31).(a) Hendrickson JB, Ramsay MVJ, Kelly TR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:6834–6843. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lewis JR, Paul JG. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1. 1981:770–775. [Google Scholar]; (c) Adeboya MO, Edwards RL, Lassoe T, Maitland DJ, Shields S, Whalley AJS. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1996:1419–1426. [Google Scholar]

- (32).(a) Andrus MB, Hicken EJ, Meredith EL, Simmons BL, Cannon JF. Org. Lett. 2003;5:3859–3862. doi: 10.1021/ol035400g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gao W, He Z, Qian Y, Zhao J, Huang Y. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:883–886. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Baldwin JE. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1976:734. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Nichols AL, Zhang P, Martin SF. Org. Lett. 2011;13:4696–4699. doi: 10.1021/ol201910v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For examples of cyclization of hindered 2-hydroxybenzoyl-p-quinones to xanthones, see:

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.