Abstract

Apathy, primarily defined as a lack of motivation, commonly occurs in people with Parkinson disease (PD). Although dysfunction of basal ganglia pathways may contribute to apathy, the role of dopamine remains largely unknown. We investigated the role of dopaminergic pathways in the manifestation of apathetic behaviors by measuring the effects of the selective dopaminergic neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) on monkeys’ willingness to attempt goal directed behaviors, distinct from their ability to perform tasks. Fifteen macaques received variable doses of MPTP, had PET scans with [11C]-dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ), [11C]-2β-3β-4-fluorophenyltropane (CFT), and [18F]-fluorodopa (FD) and performed tasks to assess apathetic behaviors and motor impairment. At 8 weeks post-MPTP, primates were euthanized and stereological cell counts and dopamine measurements were done. Apathy scores were compared to motor scores, in vitro and in vivo dopaminergic measures. Apathy scores increased following MPTP and correlated with DTBZ (rS = −0.85), CFT (rS = −0.87), and FD (rS = −0.85) specific uptake in nucleus accumbens (NAcc,) and dopaminergic cell counts in ventral tegmental area (VTA, rS = −0.80). Dopaminergic cell loss in VTA provided significant predictive power for apathy scores after controlling for the influence of cell loss in SN. Additionally, forward step-wise regression analyses indicated that neuropathological changes in the VTA-NAcc pathway predict apathetic behavior better than motor impairment or neuropathological changes in the nigrostriatal network. Our findings suggest that dopaminergic dysfunction within the VTA-NAcc pathway plays a role in the manifestation of apathetic behaviors in MPTP-lesioned primates. Similar changes in people with PD may contribute to apathy.

Keywords: apathy, parkinsonism, ventral striatum, nigrostriatal, DTBZ, limbic pathway

Introduction

Apathy, primarily defined as a lack of motivation (Marin, 1991), often manifests as a reduction in goal-directed behaviors and thoughts (Levy and Dubois, 2006; Marin, 1996; Starkstein et al. 2001) and occurs in about 30% of individuals with Parkinson disease (PD, Pluck and Brown, 2002). Although motor manifestations produce much of the disability in PD, apathy can occur before motor impairment (Pluck and Brown, 2002), diminish quality of life (Borek et al. 2006) and provide an early marker of cognitive decline (Dujardin et al. 2009). Thus, determining the underlying mechanisms that contribute to apathy and how they might differ from the pathophysiology of motor dysfunction may help direct the development of new treatments.

Loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic function produces many of the motor manifestations of PD and could contribute to apathy. Manipulation of this system with dopaminergic medication reduces apathy in some patients, but not in others (Levy et al. 2002). However, little direct evidence supports the role of dopamine or these pathways in humans. Furthermore, it is difficult to ascribe cause and effect between specific postmortem lesions and an in-life behavior like apathy. Utilizing an MPTP-lesioned primate model can overcome this limitation and provide a more direct link between behavior and in vitro assessment of the dopaminergic system.

Previous studies utilized operant learning tasks to detect deficits in goal-directed behaviors in primates receiving low-dose MPTP administration (Schneider et. al., 1988). MPTP-induced reductions in operant behavior occurred even in the absence of motor impairment in some cases. Along with these behavioral deficits, monkeys showed dopaminergic loss in both cortical and subcortical regions (including the caudate, putamen, and NAcc), as well as cell body loss in the midbrain. The severity of dopaminergic loss appeared to correspond with the degree of reductions in operant behavior. While this study did not attribute these deficits directly to apathy, it demonstrates that reductions in goal-directed behaviors can be measured in MPTP-lesioned primates and that these reductions might be related to dopaminergic decreases as determined by post-mortem analyses. However, given the relatively small sample size and small range of dopaminergic loss, it was not possible to directly relate the degree of dopaminergic pathway dysfunction to the severity of reduction of goal-directed behaviors.

Although the motor circuit of the basal ganglia, which includes input from prefrontal cortex (PFC), substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and thalamus to dorsal striatum, has been the primary focus of PD research (Lang and Lozano, 1998), the limbic pathway also may be affected in PD and includes projections from PFC, hypothalamus, amygdala and ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain that target ventromedial striatum, primarily NAcc (Carmichael and Price, 1995; Haber, 2008). The NAcc subserves cognitive and emotional functions, which are modulated by dopaminergic projections from VTA (Grace et al. 2007). Dysfunction of limbic pathways may contribute to apathy since lesions within these related networks have been linked to its clinical manifestations in humans (Bhatia and Marsden, 1994; Rosen et al. 2002; Levy and Dubois, 2006).

The present study investigates the role of dopamine in the behavioral manifestation of apathy, as defined by a lack of goal-directed behaviors, by applying a behavior rating scale to quantify the effects of MPTP as separate from MPTP-induced motor impairment. Here we extend previous studies (Schneider et. al., 1988), by injecting different doses of MPTP in monkeys, thereby inducing a wide spectrum of severity of changes in dopamine pathways, to test the dose response relationship of apathetic behaviors. Furthermore, we used in vivo and in vitro measures of subcortical dopamine pathways. We hypothesized that apathetic behaviors relate to the degree of degeneration of the VTA-NAcc dopaminergic system. We utilized in vivo PET-based measures of dopaminergic neurons in NAcc, caudate and putamen as well as unbiased stereological counts of dopamine cells in VTA. We also obtained SNpc cell counts and striatal dopamine levels to examine the specificity of the relationship between apathy and the VTA-NAcc dopaminergic system.

Methods and Materials

Subjects

Fifteen male macaques (10 Macaca fascicularis and 5 Macaca nemestrina) between the ages of 3.5 and 6.5 years old (mean = 5.4±1.0) were studied. This study was approved by the Animal Studies Committee of Washington University in St. Louis. Animals were housed in the facilities with 12-hour light and dark cycles, provided access to food and water ad libitum, and participated in various psychologically enriching activities such as playing with toys or watching movies. All animals were housed in the same room in conditions approved by the USDA. Animals were housed in the facility approximately 6 months before pre-MPTP behavioral measures.

General Procedures

Primates underwent training for behavioral exercises for at least 8 weeks before MPTP administration. During this period, each primate had a single MRI scan and two PET scans with each of three different tracers of presynaptic dopamine neurons: [11C]-dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ), [11C]-2β-3β-4-fluorophenyltropane (CFT), and [18F]-fluorodopa (FD). A variable dose of MPTP was infused unilaterally via the internal carotid artery. Following MPTP, primates continued behavioral exercises for 8 weeks. Within the final week before euthanasia, one more MRI and two PET scans with each tracer were performed. Then in vitro analyses on brain tissues were done on these same animals.

Behavioral Exercises

Animals were trained using only positive reinforcement to leave the cage, walk up and down the adjacent hallway and walk in circles using pole-and-collar technique. We also trained each animal to sit in a modified primate chair and reach for a piece of fruit with either hand 10 times each. Training was done at baseline and all sessions were recorded on digital video with at least 5 minutes of behavior for each session. These sessions were done mid-morning 2–3 times each week.

MPTP Infusion

MPTP (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was administered as described (Tabbal et al. 2006). A single MPTP dose of 0 (normal saline with no MPTP) to 0.31 mg/kg was infused into the right internal carotid artery (Kumar et al. 2009). Animals received no dopaminergic drugs at any time in this study.

Apathy Ratings

An observer blinded to MPTP dose rated each video for apathetic behaviors, using a scale developed to measure the primates’ willingness to attempt the behavioral tasks. This scale measured resistance to start walking up and down the hallway and in circles separately, providing a score for each exercise as seen in Table 1. The scale also measured apathetic behaviors during reaching exercises performed in the primate chair. The degree of coaxing and frequency of coaxing required to motivate the primate to attempt the behavior were measured for each arm separately (Table 1). Scoring was based on the maximum amount of coaxing used for that arm during all reaches. Coaxing was done in a consistent manner. If the primate failed for 5 seconds to make any attempt to reach for the piece of fruit when first presented, that fruit piece was discarded and a new piece presented. If the primate still refused to reach for the fruit, the piece of fruit was placed in the primate’s hand. Frequency of coaxing was scored by the amount of coaxing necessary, regardless of the degree. It is important to note that the ratings focus on the prolonged and sometimes active refusal to attempt the task rather than the performance of the movement itself; this helps distinguish the rating of apathy from pure motor deficits. The apathy score for each session was calculated as the total rating for each of these items with a minimum score of 6 and maximum score of 24. Five baseline ratings before MPTP were averaged to produce the pre-MPTP apathy score reflecting each primate’s normal behavior, while the final 5 measures prior to euthanasia (coinciding with the timing of the final PET scans) were averaged to produce the post-MPTP apathy score. A subset of videos was randomly selected to be rated by a second observer to assess inter-rater reliability, as well as to be rated again by the initial observer to measure intra-rater reliability.

Table 1. Apathy rating scale.

Apathy rating scale used to measure willingness to attempt behavioral task. The scale is divided into walking and reaching exercise. Hall and circle walking were scored as shown based on the amount of resistance. Reaching with the right and left arm were scored separately for degree and frequency of coaxing as shown. The minimum composite score was 6 and the maximum was 24.

| Walking Exercises

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance | None | Little | Moderate | Severe |

| Hall Walking | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Circle Walking | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Reaching Exercises | ||||

| Degree of Coaxing with Fruit | None | Prolonged Display | New Piece | Place in Hand |

| Left Arm | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Right Arm | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Frequency of Coaxing | None | 1 time | 2 times | ≥3 times |

| Left Arm | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Right Arm | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Motor Performance Ratings

An observer blinded to MPTP dose and to the apathy scores rated each video, presented in random order, for motor performance using a scale previously developed and validated for nonhuman primate studies (Tabbal et al. 2006; Perlmutter et al. 1997). Specifically, the motor scale rates the 3 parkinsonian motor features in each limb separately, namely bradykinesia, tremor, and flexed posturing on a 0 to 3 scale (0 = unaffected, 1 = mildly affected, 2 = moderately affected and 3 = severely affected). The ratings were scored for each side separately, producing a composite parkinsonism score ranging from 0 to 18 per side.

PET Scan Procedures

As an in vivo measure of dopaminergic function, all animals completed two PET scans with each tracer prior to MPTP and then two months post-MPTP using the Siemens (Knoxville, TN) MicroPET Focus 220 scanner (Tai et al. 2005). DTBZ binds to vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT-2), the pre-synaptic intracellular transporter in dopamine axons responsible for packaging dopamine into vesicles. CFT binds to dopamine transporter (DAT), the pre-synaptic membrane transporter responsible for transporting dopamine from the synaptic cleft back into the pre-synaptic neuron. FD enters the brain and is decarboxlyated to [18F]dopamine that may be stored in pre-synaptic vesicles. Each tracer reflects integrity of pre-synaptic dopaminergic nerve terminals. Fasting and anesthesia were done as described (Tabbal et al. 2006). For each scan session, a transmission scan using a Co-57 point source was used to compute attenuation coefficients and was followed by intravenous administration of 7.70–10.39 mCi DTBZ, 7.7–10.4 mCi CFT, or 3–10 mCi FD infused over 60 seconds. PET scans were collected for 120 minutes beginning with five 2-minute frames followed by 5-minute frames for FD, 60 minutes beginning with five 2-minute frames followed by 5-minute frames for DTBZ, and 120 minutes with 5-minute frames for CFT. PET image reconstruction was corrected for attenuation, scatter, randoms and deadtime with reconstructed resolution of <2.0mm in all planes (Tai et al. 2005).

PET data analysis

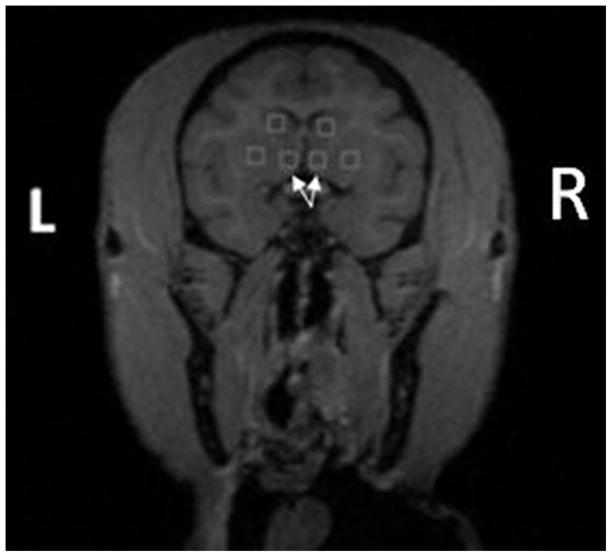

Images were processed as previously described (Tabbal et al. 2006). A reviewer blinded to MPTP dose outlined 2 × 2 mm boxes drawn within the NAcc, caudate, and putamen across 5 coronal slices, starting at the formation of the internal capsule and ending before the anterior commissure, on T1-weighted MR images (Figure 1). The occipital cortex was used as a reference region devoid of specific binding sites and comprised of a pair of hemi-cylinders on either side of the midline in occipital cortex. The MR image was co-registered to the first baseline DTBZ PET scan, and all subsequent PET scans for all tracers were aligned to the first DTBZ scan using automatic image registration (Woods and Mazziotta, 1993). The VOIs then were co-registered with the same transformation matrix to all PET images to extract tissue activity curves. After extracting these curves, the non-displaceable binding potential (BP) for CFT and DTBZ was calculated according to the tissue reference method (Logan et al. 1996) using data from 15–115 and 15–60 minutes after injection respectively. The influx constant (Kocc) was calculated for FD using data from 24–94 minutes after injection using the occipital uptake as the input function (Patlak and Blasberg, 1985).

Figure 1.

Region of interests drawn on T1-weighted MR image with the nucleus accumbens ROIs indicated by arrows. ROIs extended two slices anteriorly and posteriorly from the slice shown.

Euthanasia and In Vitro Measures

Within one day after the last PET imaging session, animals were euthanized using pentobarbital (Butler Schein Animal Health, Dublin, OH). Brains were removed rapidly and tissue was processed for striatal dopamine measurements and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunostaining to identify dopaminergic cells with subsequent stereological counts of TH neurons (Tian et al., 2012). The amount of dopamine was expressed as ng/gm of brain tissue.

Stereology

Procedures followed those defined by Gunderson, et al, (1988a, 1988b) using an Olympus BX41 Microscope with proscan stage kit and DP70 digital camera with newCAST™ software (Visiopharm, Denmark). The midbrain was divided into SNpc and VTA with the VTA defined as the area containing the parabrachial pigmented nucleus (PBP) and paranigral nucleus (PN). The SNpc was defined as the region ventral to the medial leminiscus and lateral to the third cranial nerve fibers (Figure 2), while the VTA lies dorsal to the medial leminiscus, ventral to the red nucleus, and medial to the SNpc among the third cranial nerve fibers. The VTA started just rostral of the third cranial nerve fibers and extended caudally through the extent of the SNpc. The SNpc started caudal to the hypothalamus and extended caudally to the decussation of the superior cerebral peduncle. By increasing the magnification to 10×, cell shape and size can be seen and used to differentiate between VTA and SNpc to create a more accurate outline as cells of the VTA are rounded and small, while those of the SNpc are pyramidal and large (Halliday and Tjork, 1986). newCAST™ was utilized to achieve random sampling of 5.22% (frame length/step length) of the total ROI area to reduce intra-sectional variance with an 80×80μm2 counting frame and height of 22μm with a 3μm top guard zone (Tian et al., 2012). Counting was performed on equidistant slices throughout the extent of the structures, which reduces inter-sectional variance. Dopamine cells were identified and an injected/control side ratio was calculated from cell counts for each subject.

Figure 2.

VTA and SN as outlined in the current study on TH-immunostained transverse slices. The 3rd cranial nerve fibers are indicated by arrows. The scale bar (bottom right) is 1000μm.

Statistical Analysis

To determine the reliability of the apathetic behavior scale, Cohen’s weighted-kappa statistic was computed separately for intra- and inter-rater reliability (Cohen, 1968). In addition, Cronbach’s alpha (standardized) was calculated to determine the internal consistency of the scale (Cronbach, 1951) and item to total correlations were computed to determine the overall influence of each item on the total measure. For each animal, the primary dependent measures were the apathy scores expressed as the post/pre-MPTP ratio and the VTA cell counts and PET-based measures expressed as the ratio of the injected/control side post-MPTP. We also analyzed in vitro measures of the nigrostriatal pathway, including the SNpc cell counts and striatal dopamine levels, both expressed as the post-MPTP injected/control side ratios. Apathy and motor ratings were non-normally distributed; therefore, non-parametric tests were performed for analyses including apathy or motor ratings. Mean measures before and after MPTP were compared for each dependent variable using paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed ranks test (apathy and motor). Spearman correlations were performed to determine a possible dose-response relationship between apathy and motor scores with MPTP dose. Pearson or Spearman correlations, as appropriate, were used to determine the relationship between apathy ratings, PET measures, and cell counts. To determine the strongest predictor(s) of apathetic behaviors, forward step-wise regression analyses were used to determine the ability of VTA and SNpc cell counts, NAcc and striatal tracer uptake, striatal dopamine levels, and motor ratings to predict apathy scores relative to each other. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were used to determine if cell loss in the VTA provided additional predictive power after controlling for cell loss in the SNpc. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (IBM) and plots were generated using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft).

Results

All 15 primates completed the study with a range of apathetic behaviors and motor impairment. One monkey was excluded from cell count analyses due to extensive damage to the midbrain tissue during processing procedures. Parkinsonism motor scores stabilized for all monkeys by 3 to 4 weeks and apathy ratings were relatively stable over the 8 weeks post MPTP. The apathy rating scale was found to have substantial intra-rater agreement (κ = 0.68) and moderate inter-rater agreement (κ = 0.54), as well as acceptable internal consistency (αstandardized = 0.75). The item to total correlation ranged from 0.37 to 0.58, with an average of 0.46.

Effects of MPTP on apathy and motor ratings

We found a rank order correlation between MPTP dose and apathy scores (rS = 0.77, n = 15, p = .001; Figure 3). Apathy scores were significantly higher post-MPTP than pre-MPTP (see Table 2, Wilcoxon signed-ranks test, z(14) = −2.48, p = .006). As expected, motor ratings increased after MPTP (Wilcoxon signed-ranks test z(14) = −3.04, p = .001). Apathy measures were relatively stable over 2 months after an initial post-MPTP increase; the average within subject coefficient of variation of apathy scores post-MPTP was 0.10 compared to 0.08 pre-MPTP.

Figure 3.

The relationship between MPTP dose and apathy score revealed a linear dose-response with apathy scores increasing as MPTP dose increased. Higher apathy scores indicate greater impairment. Each data point reflects the post/pre-MPTP apathy score for a single subject, and the line is the linear fit of the data.

Table 2. Mean values of pre and post-MPTP behavioral and PET-based measurements.

Mean measurements of the 15 monkeys before and after MPTP injection. Note that post-MPTP measures follow a wide range of doses, not a uniform dose.

| Measure | Pre-MPTP Mean (SD) | Post-MPTP Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Apathy Rating1* | 8.4 (1.3) | 10.0 (2.3) |

| Motor Rating1** | 0 (0) | 4 (2.6) |

| DTBZ BP NAcc** | 0.97 (0.07) | 0.66 (0.26) |

| CFT BP NAcc** | 0.95 (0.14) | 0.53 (0.33) |

| FD Kocc NAcc** | 0.99 (0.10) | 0.78 (0.29) |

| DTBZ BP Striatum** | 1.00 (0.04) | 0.49 (0.40) |

| CFT BP Striatum** | 0.99 (0.04) | 0.46 (0.41) |

| FD Kocc Striatum** | 0.98 (0.04) | 0.51 (0.41) |

Median score reported

Significant differences are noted by * (p < .05) or ** (p < .005) as determined by paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-ranks test. The median was reported for apathy and motor scores, due to its non-normal distribution. DTBZ, CFT, and FD BP and Kocc are the injected over uninjected side ratios in the NAcc and dorsal striatum before and after MPTP.

MPTP induced neurobiological changes

Specific tracer uptake in NAcc significantly decreased on the injected side compared to the control side for DTBZ (t(14) = 4.30, p < .001), CFT (t(14) = 5.62, p < .001), and FD (t(14) = 2.76, p = .01) after MPTP (see Table 2). Binding potential or Kocc decreased as MPTP dose increased (DTBZ: r = −0.78, p = .001; CFT: r = −0.67, p = .006; FD: r = −0.73, p = .002; N = 15; Figure 4). Similarly, specific tracer uptake in the dorsal striatum (caudate and putamen) significantly decreased on the injected side compared to the control side for DTBZ (t(14) = 5.31, p < .001), CFT (t(14) = 5.32, p < .001), and FD (t(14) = 4.57, p < .001) after MPTP (see Table 2). Tracer uptake decreased significantly more in the dorsal striatum than the NAcc following MPTP for DTBZ (t(14) = 4.10, p = .001), CFT (t(14) = 3.01, p = .009), and FD (t(14) = 3.37, p = .005). MPTP also induced dopaminergic cell loss in the VTA as the mean number of cells on the injected side was significantly less (t(13) = 4.83, p < .001) than the mean number of TH-stained cells on the control side (see Table 4). The ratio of cells on the injected side/control side negatively correlated to MPTP dose (r = −0.52, N = 14, p = .05; see Figure 4). VTA cell counts also correlated with DTBZ (r = 0.79, p = .001), CFT (r = 0.82, p = .001), and FD (r = 0.81, p = .001) BP (CFT, DTBZ) and Kocc (FD) in the NAcc (Figure 5). MPTP induced significant dopaminergic cell loss in the SNpc (t(13) = 4.52, p = .001) as the mean number of cells on the injected side was significantly lower than the mean number of cells on the control side, while mean residual cells in the SNpc were significantly fewer (t(13) = 4.52, p < .001) than those in the VTA (Table 4). In addition, mean striatal dopamine concentration was significantly lower (t(14) = 3.83, p = .002) on the injected side than control side (Table 4).

Figure 4.

The relationship between DTBZ (□), CFT (◇), and FD (△) specific uptake in the NAcc (top) and VTA cell counts (+, bottom) with MPTP dose. Specific tracer uptake in the NAcc decreased at a greater rate than VTA cell counts as MPTP dose increased. Each data point reflects the post-MPTP injected/control side ratio for an individual subject.

Table 4. Mean values of control and injected side dopaminergic measurements.

Mean measurements of the 15 monkeys on the injected and control sides following euthanasia. The injected side reflects changes following a wide range of MPTP doses, not a uniform dose. Residual cell counts reflect the ratio of injected side over control side in the VTA or SNpc.

| Measure | Control Side Mean (SD) | Injected Side Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| VTA Cell Counts* | 44003.2 (10937.8) | 32943.8 (9490.3) |

| SNpc Cell Counts** | 43812.6 (7919.0) | 28522.1 (13628.5) |

| Striatal dopamine ** | 22068.4 (7929.1) | 9233.8 (10732.2) |

| Residual cells VTA | --- | 0.751 (0.149) |

| Residual cells SNpc | --- | 0.616 (0.247) |

Significant differences are noted by * (p < .05) or ** (p < .005) as determined by paired t-tests.

Figure 5.

The relationship between VTA cell counts and DTBZ (□), CFT (◇), and FD (△) specific uptake in the NAcc. NAcc striatal uptake decreased linearly with cell counts in the VTA, and showed greater decrease than cell counts following MPTP injection. Each data point reflects the post-MPTP injected/control side BP or Kocc ratio for an individual subject, and the line is the linear fit of the data.

Dysfunction of the VTA-NAcc pathway was the best predictor of apathy ratings

MPTP-induced increases in apathy ratings negatively correlated with in vivo measures of binding potential in NAcc and in vitro measures of dopaminergic cell loss in VTA. Apathy ratings inversely correlated with DTBZ (rS = −0.85, p < .001, N = 15), CFT (rS = −0.87, p < .001, N = 15), and FD (rS = −0.81, p < .001, N = 15) specific uptake in NAcc and with VTA cell counts (rS = −0.80, N = 14, p = .001). The relationship between apathy ratings and the VTA-NAcc pathway (VTA cell counts and binding potential in NAcc) is shown in Figure 6. Not surprisingly, apathy also correlated with motor impairment (rS = 0.81, N = 15, p < .001), striatal dopamine concentration (rS = −0.86, N = 15, p < .001), dorsal striatal uptake of DTBZ (rS = −0.74, N = 15, p = .002), CFT (rS = −0.73, N = 15, p = .002), and FD (rS = −0.66, N = 15, p = .008), and residual cell counts in SNpc (rS = −0.70, N = 14, p = .003).

Figure 6.

The relationship between apathy scores and DTBZ (□), CFT (◇), and FD (△) specific uptake (top), and VTA cell counts (X, bottom). Apathy scores showed an inverse relationship to both NAcc tracer uptake and cell counts following MPTP. Each point represents the post/pre-MPTP apathy score and post-MPTP injected/control side measures for an individual subject, and each line is the linear fit of the data.

To determine which factors were the best predictors of apathy, we performed forward step-wise regression with an inclusion criterion of p < .05. These analyses demonstrated that VTA-NAcc pathway changes better predicted apathy scores than changes in nigrostriatal pathways or motor ratings. With VTA cell counts and motor ratings as independent variables, VTA cell counts was a significant predictor of apathy ratings (R2 = 0.68, F(1, 12) = 25.76, p < .001), but motor ratings were excluded from the regression model (p = .12). With DTBZ, CFT, or FD specific uptake in NAcc and motor ratings as independent variables, tracer uptake in NAcc was a significant predictor of apathy ratings for DTBZ (R2 = 0.65, F(1,13) = 23.92, p < .001), CFT (R2 = 0.65, F(1,13) = 23.97, p < .001), and FD (R2 = 0.68, F(1,13) = 28.16, p < .001), but motor ratings were again excluded from the regression model (all p ≥ .20). With DTBZ, CFT, or FD uptake in NAcc and striatal dopamine as independent variables, tracer uptake in NAcc was a significant predictor of apathy for DTBZ (R2 = 0.65, F(1,13) = 23.92, p < .001), CFT (R2 = 0.65, F(1,13) = 23.97, p < .001), and FD (R2 = 0.68, F(1,13) = 28.16, p < .001), but striatal dopamine concentration was excluded from the regression model (all p ≥ .23). Similarly, with DTBZ, CFT, or FD uptake in the NAcc and the same measures in the dorsal striatum as independent variables, tracer uptake in the NAcc was a significant predictor of apathy for DTBZ (R2 = 0.65, F(1,13) = 23.92, p < .001), CFT (R2 = 0.65, F(1,13) = 23.97, p < .001), and FD (R2 = 0.68, F(1,13) = 28.16, p < .001), but dorsal striatal uptake of DTBZ (p = .71), CFT (p = .74), and FD (p = .78) again was excluded from the regression model. We also performed hierarchical multiple regressions to determine the additional predictive power of dopaminergic cell loss in the limbic pathway after controlling for the influence of the nigrostriatal pathway. Even after controlling for SNpc cell loss, VTA cell loss accounted for an additional 9.6% of the variance in apathy ratings (F change (1,11) = 5.03, p <.05).

Discussion

This study sheds new light on the involvement of dopaminergic pathways in the manifestation of apathy in MPTP-lesioned monkeys. Apathy ratings increased in a dose-dependent manner following MPTP, suggesting that damage to the dopaminergic system causes apathetic behaviors. MPTP-induced increases in apathy scores correlated with in vivo measures of dopaminergic function in the NAcc and with in vitro measures of dopaminergic cell counts in the VTA. While increases in apathetic behavior also correlated with dopamine dysfunction in the motor pathway and motor scores, neuropathological changes in the VTA-NAcc pathway better predicted increases in apathy ratings than motor impairment or neuropathological changes in the nigrostriatal pathway. Our findings suggest that decreased function of the VTA-NAcc dopaminergic pathway may play a key role in the manifestation of apathy.

Apathy ratings increase following MPTP

Apathy ratings revealed that primates’ willingness to attempt goal-directed behaviors decreases following MPTP. This was manifested by physical resistance to beginning walking exercises and lack of any effort to begin to reach for fruit pieces without coaxing. Our behavioral findings are similar to those of Schneider et. al., (1988), as the primates developed a lack of interest in performing trained tasks following MPTP. Although as expected motor impairment correlated with apathy ratings, this was likely due in part to the shared causative factor of MPTP, as supported by our forward stepwise regression analysis.

MPTP induces dopaminergic dysfunction in the VTA-NAcc pathway

We show that MPTP induces dose-responsive cell death in the VTA as well as in SNpc, as previously demonstrated (German et al. 1988), and extend these findings to PET measures of dopaminergic terminal integrity in the NAcc. MPTP induced significant VTA cell loss and decreases in specific uptake of PET radiotracers in NAcc, although the severity of the reductions were greater in the nigrostriatal pathway measures including SNpc cells, specific uptake of PET tracers in dorsal striatum and striatal dopamine concentration.

VTA-NAcc pathway dysfunction is the best predictor of increased apathetic behavior

Apathy ratings showed correlations with dopamine loss in both the VTA-NAcc pathway and the nigrostriatal pathway. In fact, our findings reveal that increased cell loss in the VTA and diminished uptake of dopaminergic tracers in the NAcc were stronger predictors of increased apathetic behavior than cell loss in the SNpc, striatal dopamine concentration, striatal tracer uptake, or motor impairment. In addition, VTA cell loss provided significant predictive power, even after controlling for the shared power provided by SNpc cell loss. These findings suggest that dopaminergic loss contributes to the manifestation of apathy in the MPTP model, and specifically that dopamine loss in the VTA-NAcc pathway contributes more than SNpc pathway loss. The role of dopamine dysfunction within the NAcc is further supported by the converging evidence provided by three different dopaminergic PET radiotracers. The limited resolution of the MicroPET does not completely separate measurements of ventral striatum from dorsal striatum but the separation of these structures is at least twice the distance of the resolution of the images making this issue relatively minor.

The finding that impairment within dopaminergic pathways is associated with the manifestation of apathy agrees with previous observations in humans. Previous studies revealed that levodopa or dopamine agonists may ameliorate apathetic behaviors, and previous neuroimaging studies found that decreased dopaminergic function in the ventral striatum correlated with increased apathy (Czerncecki et al. 2002; Lemke et al. 2006; Remy et al. 2005). Our findings also support the dopamine reward prediction hypothesis, which proposes that dopamine modulates NAcc cells to determine whether the benefit of reward outweighs the cost of the required behavior (Grace et al. 2007). MPTP-induced dopaminergic deficits could impair this specific modulation and thereby decrease goal-directed behaviors. Importantly, our results suggest that a decrease in dopaminergic modulation occurs in the limbic loop of the basal ganglia and may not depend only on dysfunction of motor circuits.

Other considerations

Although the present study demonstrates a strong relationship between apathetic behaviors and dopaminergic dysfunction, especially in the NAcc-VTA pathway, other factors may contribute, including a smaller but significant contribution from the nigrostriatal system and its connections (Haber et al. 2000). We cannot exclude the possibility that damage to both pathways is necessary for the manifestation of apathy. Other cortical and subcortical regions as well as other neurotransmitter systems may be involved in apathy, and in fact Schneider, et al. (1988) found alterations to dopaminergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic systems following chronic MPTP injections. Lesions within the ventromedial PFC or the caudate (Bhatia and Marsden, 1994) can induce similar disparities in goal-directed behaviors and response to reward cues (Bechara et al. 2000). In addition, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can induce reversible apathy, suggesting a role of the serotonin system in some cases (Barnhart et al. 2004). Finally, the cholinesterase inhibitor rivastigmine may modestly reduce apathy in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies, implicating the cholinergic system in apathetic behaviors (McKeith et al. 2000). Additional studies are needed to examine these other networks and neurotransmitter systems following dopaminergic lesions.

Limitations and Strengths of Design

While the current study provides evidence for the role of dopaminergic loss in the manifestation of apathetic behaviors, it is important to note that MPTP provides a model of dopaminergic loss that does not necessarily match the pathology of PD. In addition, by using an animal model, we were only able to assess apathy through observable behavior rather than including reports of mood or thoughts, which are also components of apathy. It also should be noted that inter-rater reliability of the apathetic behavior scale was moderate, so a single observer performed all ratings in the current study. Although we did measure apathetic behaviors and motor impairment, we did not test whether there were any cognitive deficits that may contribute to decreases in goal-directed behaviors. Additionally, we only measured alterations within the dopaminergic system, which in our study were unilateral. There may have been contributions from deficits in other neurotransmitter systems that may or may not have remained unilateral. Additionally there could be compensatory action from the unlesioned hemisphere that was not accounted for in this study.

However, we were able to successfully measure dopaminergic function both in vivo and in vitro in a relatively large sample of primates receiving a wide range of MPTP doses. This provided a full spectrum of dopaminergic loss as well as behavioral and motor deficits. Additionally, the unilateral model allowed for within-subjects comparisons, thus negating much of the inter-subject variance seen in response to MPTP injection. This also permits the monkeys to continue to care for themselves following MPTP, preventing the potential need for dopaminergic medication to reduce disability, which would confound our study. Finally, we specifically assessed the role of the limbic and motor subcortical dopaminergic pathways separately in the manifestation of apathetic behaviors through investigating both cell body loss and decreased function in the terminal fields.

Conclusion

We demonstrated that goal-directed behaviors decrease following MPTP and that this behavioral deficit is directly related to dopaminergic dysfunction. Furthermore, we provide preliminary evidence that dysfunction of the VTA-NAcc limbic pathway predicts the increase in apathetic behaviors better than dopaminergic dysfunction in the nigrostriatal pathway or motor impairment itself. Additional studies are needed to determine the role of frontal-striatal pathways and other neurotransmitter systems in the reduction of goal-directed behaviors in MPTP-lesioned primates.

Table 3. Summary of results from 15 monkeys.

Summary of each monkey’s MPTP dose, age at MPTP injection, Parkinsonism score, apathy score, cell counts, and DTBZ, CFT, and FD specific striatal uptake. MPTP dose is given in mg/kg and motor score is the final score at 2 months post-MPTP. Apathy ratio is the post/pre-MPTP ratio; specific tracer uptake ratio in NAcc is the injected/control side ratio post-MPTP, with BP values used for DTBZ and CFT and Kocc used for FD; VTA count ratio is the injected/control side ratio of cell counts.

| Monkey number | Age | MPTP dose | Motor Score | Apathy | NAcc Specific Uptake | VTA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- MPTP | Post- MPTP | Ratio | DTBZ Ratio | CFT Ratio | FD Ratio | Count Ratio | ||||

| 1a | 5.8 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 8.4 | 0.84 | 1.01 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 0.94 |

| 2 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 7.8 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.90 |

| 3 | 5.6 | 0.07 | 3 | 10.4 | 11.1 | 1.07 | 0.73 | 0.49 | 0.74 | 0.90 |

| 4a | 3.5 | 0.08 | 3 | 7 | 8.2 | 1.17 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.64 |

| 5a | 3.7 | 0.12 | 3 | 7.4 | 6.2 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.90 | 0.74 |

| 6 | 5.3 | 0.13 | 2 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 1.05 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 1.06 | 0.98 |

| 7 | 4.5 | 0.13 | 0 | 8.8 | 10.2 | 1.16 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.86 |

| 8 | 6.3 | 0.13 | 6 | 8.4 | 11.2 | 1.33 | 0.59 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.61 |

| 9 | 6.3 | 0.14 | 8 | 9.6 | 14.6 | 1.52 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.64 | 0.61 |

| 10 | 6.4 | 0.14 | 4 | 8.2 | 9.6 | 1.17 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.84 |

| 11 | 6.4 | 0.14 | 5 | 8.4 | 13.6 | 1.62 | 0.62 | 0.18 | 0.59 | 0.58 |

| 12 | 5.1 | 0.19 | 6 | 10.4 | 13.7 | 1.32 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.64 | -- |

| 13a | 4.1 | 0.20 | 7 | 7 | 9.8 | 1.40 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.56 |

| 14a | 5.5 | 0.24 | 6 | 6.67 | 10 | 1.50 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.51 | 0.64 |

| 15 | 5.6 | 0.31 | 7 | 7.6 | 10.8 | 1.42 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.40 | 0.70 |

M. nemenstrina

Highlights.

MPTP induces increased apathetic behaviors in non-human primates

Nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area show dopaminergic loss following MPTP

Dopamine loss in accumbens and ventral tegmental predicts apathetic behaviors

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH (NS050425, NS058714, NS41509, and NS075321); Michael J Fox Foundation; Murphy Fund; American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA) Center for Advanced PD Research at Washington University; Greater St. Louis Chapter of the APDA; McDonnell Center for Higher Brain Function; Hartke Fund; Howard Hughes Medical Institute; Parkinson’s Disease Foundation; and Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation (Elliot H. Stein Family Fund and PD Research Fund). We thank Hugh Flores, Christina Zukas, Darryl Craig, Cedric Huchuan Xia, Iboro Umana, and Terry Anderson for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

All authors report no financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barnhart JW, Makela EH, Latocha MJ. SSRI-induced apathy syndrome: A clinical review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10:196–199. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR. Emotion, decision making, and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:295–307. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia KP, Marsden CD. The behavioral and motor consequences of focal lesions of the basal ganglia in man. Brain. 1994;117:859–876. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.4.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borek LL, Amick MM, Friedman JH. Non-motor aspects of Parkinson’s disease. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:541–554. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900013560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST, Price JL. Sensory and premotor connections of the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1995;346:642–664. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull. 1968;70:213–220. doi: 10.1037/h0026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Czernecki V, Pillon B, Houeto JL, Pochon JB, Dubois B. Motivation, reward, and Parkinson’s disease: influence of dopatherapy. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:2257–2267. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin K, Sockeel P, Delliaux M, Destée A, Defebvre L. Apathy may herald cognitive decline and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:2391–2397. doi: 10.1002/mds.22843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German DC, Manaye KF, Sonsalla PK, Brooks BA. 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced Parkinsonian syndrome in Maccaca fascicularis: which midbrain dopaminergic neurons are lost? Neurosci. 1988;24:161–174. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA, Floresco SB, Goto Y, Lodge DJ. Regulation of firing of dopaminergic neurons and control of goal-directed behaviors. Trends Nuerosci. 2007;30:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson HJG, et al. The new stereological tools: Dissector, fractionators, nucleator and point sampled intercepts and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. APMIS. 1988a;96:857–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1988.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson HJG, et al. Some new, simple and efficient stereological methods and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. APMIS. 1988b;96:379–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1988.tb05320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN. Functional Anatomy and Physiology of the Basal Ganglia: Non-motor Functions. In: Tarsy D, Vitek JL, Star PA, Okun ML, editors. Current Clinical Neurology: Deep Brain Stimulation in Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. 2008. pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, Fudge JL, McFarland NR. Striatonigrostriatal pathways in primates form an ascending spiral from the shell to the dorsolateral striatum. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2369–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02369.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday JM, Tjork I. Comparative anatomy of the ventromedial mesencephalic tegmentum in the rat, cat, monkey and human. J Comp Neurol. 1986;252:423–445. doi: 10.1002/cne.902520402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Lee JJ, Perlmutter JS, Derdeyn CP. Cervical carotid and Circle of Willis arterial anatomy of Macaque monkeys: A comparative anatomy study. Anatomic Record. 2009;292:976–84. doi: 10.1002/ar.20891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AE, Lozano AM. Parkinson’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1044–1053. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke MR, Brecht HM, Koester J, Reichmann H. Effects of the dopamine agonist pramipexole on depression, anhedonia, and motor functioning in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurological Sciences. 2006;248:266–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy G, et al. Memory and executive function and impairment predict dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17:1221–1226. doi: 10.1002/mds.10280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R, Dubois B. Apathy and Functional Anatomy of the Prefrontal Cortex-Basal Ganglia Circuits. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:916–928. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J, et al. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:834–840. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin RS. Apathy: a neuropsychiatric syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;3:243–254. doi: 10.1176/jnp.3.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin RS. Apathy: concept, syndrome, neural mechanisms, and treatment. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 1996;1:304–314. doi: 10.1053/SCNP00100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith I, et al. Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled international study. Lancet. 2000;356:2031–2036. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patlak CS, Blasberg RG. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data: Generalizations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985;5:584–590. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1985.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter JS, Tempel LW, Black JK, Parkinson D, Todd RD. MPTP induced dystonia and parkinsonism: Clues to the pathophysiology of dystonia. Neurology. 1997;49:1432–1438. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.5.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluck GC, Brown RG. Apathy in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:636–642. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.6.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remy P, Doder M, Lees A, Turianski N, Brooks D. Depression in Parkinson’s disease: loss of dopamine and noradrenaline innervation in the limbic system. Brain. 2005;128:1314–1322. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen HJ, et al. Patterns of brain atrophy in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. Neurology. 2002;58:198–208. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JS, Unguez G, Yuwiler A, Berg SC, Markham CH. Deficits in operant behavior in monkeys treated with N-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) Brain. 1988;111:1265–1285. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.6.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkstein SE, Petracca G, Chermerinski E, Kremer J. Syndromatic validity of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pyshciatry. 2001;158:872–877. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabbal SD, et al. 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced acute transient dystonia in monkeys associated with low striatal dopamine. Neurosci. 2006;141:1281–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai YC, et al. Performance evaluation of the microPET Focus: A third-generation microPET scanner dedicated to animal imaging. J Nuc Med. 2005;46:455–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian LL, Karimi M, Loftin SK, Brown CA, Xia H, Xu J, Mach RH, Perlmutter JS. No differential regulation of dopamine transporter (DAT) and vesicular monamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) binding in primate model of Parkinson disease. PLoSOne. 2012;7:e31439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RP, Mazziotta JC. Automated intersubject registration. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:S818. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]