Abstract

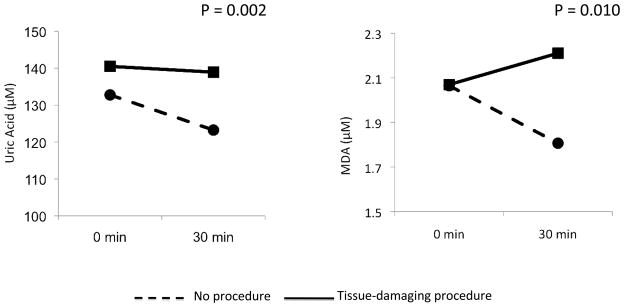

Preterm neonates exposed to painful NICU procedures exhibit increased pain scores and alterations in oxygenation and heart rate. It is unclear whether these physiologic responses increase the risk of oxidative stress. Using a prospective study design, we examined the relationship between a tissue-damaging procedure (TDP, tape removal during discontinuation of an indwelling central arterial or venous catheter) and oxidative stress in 80 preterm neonates. Oxidative stress was quantified by measuring uric acid (UA) and malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration in plasma before and after neonates experienced a TDP (n=38) compared to those not experiencing any TDP (control group, n=42). Pain was measured before and during the TDP using the Premature Infant Pain Profile(PIPP). We found that pain scores were higher in the TDP group compared to the control group (median scores:11 and 5, respectively, P<0.001). UA significantly decreased over time in control neonates but remained stable in TDP neonates (132.76μM to 123.23μM vs.140.50μM to 138.9μM, P=0.002). MDA levels decreased over time in control neonates but increased in TDP neonates (2.07μM to 1.81μM vs. 2.07μM to 2.21μM, P=0.01). We found significant positive correlations between PIPP scores and MDA. Our data suggest a significant relationship between procedural pain and oxidative stress in preterm neonates.

Keywords: Neonate, procedural pain, uric acid, MDA

Introduction

During a typical stay in the NICU a newborn often experiences numerous painful procedures in the course of monitoring and treatment. Contrary to previously held beliefs, premature neonates are able to perceive pain4 as demonstrated by several pain scoring methods 34. Such methods, however, tend to rely on a neonate’s alertness and ability to react expressively to painful experiences. Consequently, caregivers are reluctant to prevent or treat pain if there appears to be no clear demonstration that it is occurring or if no immediate untoward effects are observed 41. An approach that involves measurement of a systemic biochemical reaction to a painful stimulus has the potential benefit of providing objective means of evaluating the presence and degree of pain as well as the effectiveness of its treatment.

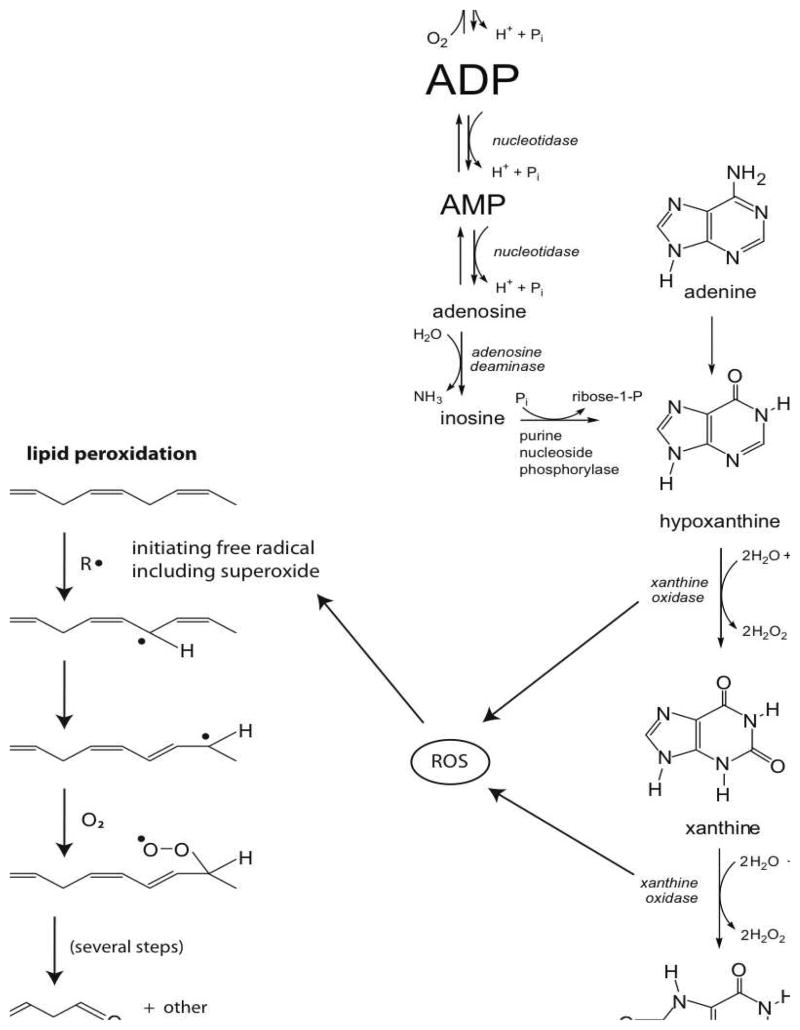

It is well documented that exposure to painful procedures often results in tachycardia and reductions in oxygen saturation, which increases energy expenditure and oxygen consumption7. However, there is currently little data that quantify the effects of increased pain and oxygen consumption on ATP metabolism. Theoretically, an increase in oxygen consumption should increase the utilization and degradation of ATP to its purine by-products, specifically uric acid (Figure 1). We made this observation in a pilot study from our laboratory where we reported increased uric acid concentration in rabbit kits subjected to a single heel lance32 Because the process of purine degradation can result in the production of hydrogen peroxide, markers of oxidative stress can theoretically increase. This, in fact, was observed by Belliene, et. al. who showed increased markers of oxidative stress in the plasma of premature neonates experiencing a single heel lance8. However, no studies to date have examined the relationship between pain scores that reflect behavioral and physiological markers of pain and plasma markers of ATP utilization and oxidative stress. Specifically, do markers of ATP utilization and oxidative stress increase as pain scores increase?

Figure 1.

Pathway from ATP to Uric Acid and MDA

To explore this question, we studied two groups of preterm neonates: one group experiencing a common tissue damaging procedure (TDP group) and a second group not experiencing any TDP (control group). The TDP was tape removal associated with the discontinuation of a central arterial or venous catheter. Pain was measured before and during the TDP using the Premature Infant Pain Profile (PIPP), whose components include physiological (gestational age, heart rate, oxygen saturation) and behavioral (state and facial expressions) markers. ATP degradation was quantified by measuring uric acid (UA) levels and oxidative stress was quantified by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) in plasma obtained before and after the TDP. Uric acid is a well-known end product of purine metabolism whose concentration is associated with increased ATP utilization, hypoxia, ischemia or increased reactive oxygen species (ROS)21 (Figure 1). MDA is a thiobarbituric acid–reacting substance that is formed by the action of reactive oxygen species on lipid membranes29, 38 (Figure 1). Its use as a marker is relevant because although the study of oxidative stress and pain in neonates is relatively recent, the association of pain with elevated MDA is not novel and has been reported in adults. Elevated MDA concentrations were observed in adult patients with vascular related pain36, young women with dysmenorrheal pain19, 43, adults with neuropathic pain14 and adult patients with acute abdominal pain15. More recently, MDA and 8-hydroxyguanosine were reported to significantly correlate with pain intensity in patients with temporomandibular joint disease35.

Evaluation of the effects of pain in premature neonates is challenging. We present biochemical evidence that a single painful procedure is associated with a system wide perturbation in purine metabolism and oxidative stress. Furthermore, we show that a single TDP correlates with elevated MDA levels and PIPP scores, suggesting distant effects in the form of oxidative damage to lipid membranes.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study at the Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital NICU. The Loma Linda University Institutional Review Board approved our study protocol and informed consent documents. Families were approached for consent as soon as possible after birth.

Preterm infants less than 37 weeks gestation that met the following inclusion criteria were considered for enrollment: (1) weight of more than 1000 grams at time of enrollment, (2) arterial or central venous catheter in place, (3) no signs or symptoms of hypoglycemia, hypovolemia, hypoperfusion, hyperbilirubinemia, clinical sepsis, pallor or moderate to severe respiratory distress, (4) absence of intraventricular hemorrhage grade 3 or higher and (5) parental consent. Exclusion criteria included (1) multiple congenital abnormalities (2) facial malformation, (3) complex congenital heart disease (4) receiving analgesia or sedation and (5) endotracheal intubation.

After parental consent was obtained, investigators collaborated with the clinical staff to obtain from a central catheter approximately 0.8 ml of blood before and 30 minutes after the TDP to measure UA and MDA levels. In control neonates, similar samples were obtained at “0” and 30 minutes from baseline. The time period of 30 minutes after TDP for blood sample collection was based on previous investigations which showed plasma levels of MDA significantly increasing 15–30 minutes after ischemia-reperfusion30, 44 and remaining elevated up to 2 hours later23. Our pilot study in rabbit kits also showed elevations of uric acid thirty minutes after a single heel lance32. To isolate the effects of TDP, subjects were given at least one hour of “quiet time” in which no TDPs were performed before baseline blood samples were drawn and no additional TDPs were performed during the study period. Samples were centrifuged within five minutes to separate cells from plasma which was then stored at −80°C. All stored plasma samples were analyzed within one week of acquisition.

Pain Assessment

To assess pain, we used the Premature Infant Pain Profile (PIPP), an instrument that was designed to assess acute pain in preterm neonates40. The scoring system includes seven items, each graded from 0 to 3. Two items describe baseline characteristics of the neonate (gestational age and behavioral state), two items are derived from physiologic measurements (heart rate and oxygen saturation), and three items describe facial actions (brow bulge, eye squeeze, and nasolabial furrow). Gestational age, behavioral state, heart rate and oxygen saturation were assessed and recorded by a trained research nurse (LS) at the bedside. Facial actions were assessed and scored by a neonatologist who was blinded to group assignment (KH), who had undergone training in the use of the PIPP and was experienced in observing and quantifying facial actions. Previous work on validation of the PIPP score showed an ability to differentiate painful from non-painful or baseline events (F = 48; P = .0001), with interrater reliability coefficients of 0.93 to 0.96 and intrarater reliability coefficients were 0.94 to 0.985, 12, 40.

Measurement of MDA

Plasma MDA levels were determined using an adaptation of the selected ion-monitoring gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) analysis of phenylhydrazine-derivatized plasma, as described by Cighetti et al17. Specifically, the sample was prepared by the mixture of 0.1 ml plasma, 0.26 nmol methyl malondialdehyde (MMDA), 5 nmol butylated hydroxytoluene (10 μl of 0.5 mM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 0.2 ml citrate buffer (0.4 M, pH 4.0), and deionized water, up to a final volume of 480 μl. Then 20μl 50 mM phenylhydrazine (1 μmol) (Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added as the derivatizing agent. After 30 min incubation at 25°C, the samples were extracted with 1 ml hexane, vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged (3000 rpm, 10 min) at 25°C. The organic phase was removed, concentrated by nitrogen stream to 100 μl, and analyzed by GC-MS, in selected ion monitoring mode (injection volume of 2 μl). Ion 144.00 was monitored for MDA, and ion 158.00 for MMDA. The ion abundance ratios were converted to micromolar concentrations by use of a standard curve. All measurements were performed in triplicate. Values with coefficients of variation of less than 10% were included in the final analyses.

The internal standard, MMDA, was synthesized using a modified method of Paroni et al31. Briefly, 2-methyl-3-ethoxyprop-2-enal (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) was suspended in 7 M NaOH and stirred for 150 min. This was diluted with 5 ml of water and extracted with three 5 ml volumes of CH2Cl2. Water was then evaporated from the aqueous layer. The residue was crystallized once from 5 ml ethanol and 5 ml benzene and then three times from 5 ml ethanol and 5 ml diisopropyl ether. The resulting white powder was diluted in water, filtered, and stored at −80°C.

Measurement of Uric Acid

Plasma was transferred to separate Eppendorf tubes, and immediately centrifuged within 5 minutes in Beckman Microfuge 22R (Fullerton, CA) for 30 minutes at 18000 × g, 4°C. The supernatant was immediately transferred to Microcon centrifugal filter devices (Millipore Corp.; Bedford, MA), 200 μl per device, and spun for 90 min at 14000 × g, 4°C. Filtrate was removed, and 150 μl was transferred to an Eppendorf tube containing 1 × 10−7 mol of 2-aminopurine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as the internal standard. Analysis was done the same day using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Waters 996 PDA, 715 Ultra Wisp Sample Processor; Millipore Corp) or the tubes were frozen at −80°C until analysis could be performed. Previous HPLC analysis demonstrated that uric acid values remained stable despite freezing.

Three 45 μl injections were used for each sample. Samples were injected onto a Supelcosil LC-18-S 15 cm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm column (Supelco, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), with the following isocratic conditions: 50 mM ammonium formate buffer, pH 5.5, flow rate 1.0 ml/min. Uric acid concentration was quantitated by first obtaining integrated peak areas for uric acid and for 2-aminopurine at appropriate retention times and wavelengths, as described by our laboratory11. Then the peak area ratios of uric acid to 2-aminopurine were determined and converted to micromolar concentrations using standard curves. Samples were analyzed in triplicates and values with coefficients of variation of less than 10% were included in the final analyses. The limit of detection for uric acid was 5.0 μM.

Statistics

At the time our study was planned, there were no studies that had examined the relationship between pain and oxidative stress in premature neonates. We based our sample-size calculation on our pilot study that compared MDA and UA concentration in neonates born by elective cesarean section to those born by vaginal birth11. Based on that calculation, 35 subjects per group were required to demonstrate a difference between groups with 80% power and α = .05 (Sample Power 2.0 [SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL]). We recruited additional subjects per group to account for data-collection errors. The total sample size was 80 infants (Control n = 42 and TDP n = 38).

Assumptions of normality and equal variance were assessed. Demographic data for categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square test. Repeated measures ANOVA for one between subject factor (group) and one within subject factor (time) were assessed to evaluate the effect of the procedure (control vs. TDP) on plasma UA and MDA concentrations over time. Interaction terms in the General Linear Model were used for this purpose. Percent change in UA, as well as MDA, between baseline and thirty-minute values were calculated as follows:

Correlations between UA, MDA and biobehavioral markers (PIPP) were examined using Spearman’s rho. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 17. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

General Results

Subject recruitment occurred from July 2007 to August 2009. After obtaining parental consent, samples were obtained from 80 subjects that met study criteria. As described in Table 1, no significant differences in demographics were found between the control and TDP group. The clinical characteristics and the environmental condition of subjects at the time of sampling were also compared (Table 2). At the time of sampling, no significant differences were observed in mode of ventilation, baseline oxygen saturation, postnatal age, fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), hemoglobin, acuity (as measured by SNAPPE-II), environmental noise, kidney function (as measured by BUN and creatinine) and number of exposure to TDPs (Table 2).

Table 1.

Subject demographics

| No procedure | Tissue-Damaging Procedure (TDP) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 42 | 38 | |

| Birth weight | 1644 ± 486 g | 1637 ± 499 g | NS |

| Estimated gestational age | 31.2 ± 3 weeks | 31.2 ± 3 weeks | NS |

| Gender | Male – 54.1% | Male – 54.1% | NS+ |

| Apgar – 1 minute | 6 ± 2.0 | 6 ± 3.0 | NS |

| Apgar – 5 minute | 8 ± 2 | 7 ± 3 | NS |

| Race | Caucasian – 52.4% | Caucasian – 39.5% | NS+ |

| Hispanic – 23.8% | Hispanic – 44.7% | ||

| African-American – 14.3% | African-American - 10.5% | ||

| Asian – 7.1% | Asian – 5.3% | ||

| Not documented 2.4% | Not documented – 0% | ||

Mean ± SD

Independent samples t-test;

Chi-square

Table 2.

Physiological and Environmental Conditions at Time of Sampling

| No procedure (n=42) | Tissue-Damaging Procedure (TDP) (n=38) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FiO2 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.24 ± 0.07 | NS |

| Mode of ventilation | Room Air = 24 (57.1%) | Room Air = 26 (68.4%) | NS |

| Nasal Cannula = 9 (21.4%) | Nasal Cannula = 4 (10.5%) | ||

| Nasal CPAP = 6 (14.3%) | Nasal CPAP = 5 (13.1%) | ||

| NIPPV = 3 (7.1%) | NIPPV = 3 (7.9%) | ||

| Baseline oxygen saturation (%) | 97 ± 2.8 | 97 ± 3.6 | NS |

| Postnatal Age (in days) | 20 ± 12 | 20 ± 15 | NS |

| Weight (g) | 1850 ± 515 | 1890 ± 568 | NS |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 12.7 ± 2.2 | 13.2 ± 2.2 | NS |

| SNAPPE II score | 7.9 ± 3.6 | 7.6 ± 5.5 | NS |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 16.8 ± 10.6 | 14.8 ± 8.3 | NS |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.47 ± 0.19 | 0.46 ± 0.18 | NS |

| # of TDPs from birth to time of sampling | 95 ± 69 | 107 ± 96 | NS |

| Environmental Noise (dB) | 51 ± 5 | 53 ± 4 | NS |

Mean ± SD

Independent samples t-test

FiO2 – fraction of inspired oxygen

SNAPPE II – Score of Neonatal Acute Physiology- Perinatal Extension II

Procedural Pain Score as measured by PIPP

As expected, neonates in the TDP group had significantly higher procedural pain scores compared to the control group (Table 3). Median procedural pain scores were as follows: control group: 5 (min–max 0–11) and TDP group: 11 (min–max 3–19), P < 0.001 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pain Score as measured by PIPP+

| No procedure (n=42) | Tissue-Damaging Procedure (TDP) (n=38) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Pain Score (median) | 3 (0–7) | 3 (0–8) | NS |

| Procedural Pain Score (median) | 5 (0–11) | 11 (3–19) | <0.001 |

PIPP – Premature Infant Pain Profile

Mann-Whitney

Differences between Baseline and Post-procedure Uric Acid and MDA Levels in Control vs. TDP Groups

There were no significant differences in baseline uric acid and MDA levels between control and TDP groups. However, although uric acid levels decreased over time in the control group, uric acid levels remained unchanged in the TDP group (Figure 2). More importantly, we saw a significant increase in MDA over time in the TDP group that was not observed in the control group (P = 0.02) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Plasma [UA] and [MDA] at baseline and thirty minutes post TDP

Correlation between PIPP Pain Score and MDA

We found significant correlations between pain scores and MDA (Pearson correlation, 0.283, P = 0.012). As the pain score increased, MDA levels also increased. In addition, we found significant correlations between procedural heart rate and MDA (Correlation Coefficient 0.286, P = 0.014). We observed that as heart rate increased, MDA concentration also increased. More importantly, we also found a significant correlation between MDA and oxygen saturation; as oxygen saturation decreased, MDA concentration increased (Correlation coefficient, 0.454, P <0.001). We found no significant correlation between plasma UA levels and total PIPP pain scores.

Discussion

Premature neonates in the intensive care unit have reduced endogenous substrate fuel stores and metabolic reserve33. Their ability to respond to acute stressors is limited due to their physiologic immaturity, which impedes their ability to mobilize substrate during catabolic metabolism16. Their response to routine NICU procedures often include significant alterations in transcutaneous oxygen levels (TcPO2) and heart rate 18, 39. Because neonates have fixed stroke volumes, acute changes in heart rate can potentially reduce cardiac output and cause tissue hypoperfusion, increasing the risk of ischemia before compensatory mechanisms take effect. Ischemia combined with decreased arterial oxygen tension can contribute to increased adenosine trisphosphate (ATP) utilization in the face of decreased ATP synthesis. This can lead to enhanced degradation of ATP to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and adenosine monophosphate (AMP)24. Further degradation leads to dramatic increases in adenosine levels. In turn, adenosine is converted to inosine and subsequently to hypoxanthine, xanthine, and uric acid (Figure 1). During conditions of decreased ATP supply, the enzyme xanthine oxidase is activated catalyzing the conversion of hypoxanthine to xanthine and xanthine to uric acid, while generating reactive oxygen species37. In this context, there has been little research evaluating the link between painful procedures, increased ATP utilization and oxidative stress in premature neonates.

Our data demonstrate a significant relationship between procedural pain and MDA, a well-accepted marker of oxidative stress. Specifically, we observed an increase in MDA in preterm neonates exposed to a single painful procedure compared to those who were not exposed to such procedure. None of the neonates in this study had conditions that were shown to increase plasma MDA concentration such as moderate to severe respiratory distress, elevated FiO2 requirements, lipid infusions, hyperbilirubinemia6, 26 or clinical signs of septicemia25. Instead, the elevated MDA is consistent with an increase in the production of reactive oxygen species secondary to enhanced ATP degradation (Figure 1) in response to increased energy requirements and reduced oxygenation brought about by the painful procedure. Elevations in heart rate and reductions in oxygen saturation significantly correlated with elevated MDA levels. Further studies are required to investigate this mechanism as well as other possible mechanisms that may increase MDA such as pain-related tissue injury, inflammation and cytokine production. To validate the relationship between procedural pain and oxidative stress, it will also be important to measure other oxidative stress markers, such as damage to DNA (8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine), lipids (4-hydroxy-2-noneal, isoprostanes, isofurans) and nitration of proteins (plasma nitroalbumin, peroxynitrite marker nitrotyrosine [3-nitro-4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (NHPA), para-hydroxyphenylacetic acid) in plasma and other biological fluids10, 22, 42.

Our findings have important implications for clinical practice. Because neonates are exposed to multiple painful procedures per day13, 28, previous investigations have focused on examining and decreasing the painful effects of these procedures. A number of interventions, such as the use of sucrose1, 9, 27, pacifiers2, 9, or morphine3, 20 have been successful in decreasing signs of pain, but studies investigating the possible biochemical sequelae of painful procedures in neonates are needed. If exposure to multiple painful procedures is shown to contribute to oxidative stress, biochemical markers of such stress might be useful in evaluating mechanism-based interventions that could decrease the adverse effects of exposure to these procedures.

Although our findings are novel in the neonatal population, our study was performed without randomization. The painful procedure (tape removal) was a clinical requirement necessary in the normal course of care in the NICU setting, and no additional painful procedures were employed solely for the benefit of a randomized experimental protocol. However, as shown in Table 1, the demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects in both the control and TDP groups were not significantly different. All of the subjects were clinically stable premature neonates, with minimal oxygen requirements and similar clinical acuity status. Randomized trials that examine the biochemical effect of painful procedures in more acutely ill neonates with higher SNAPPE II scores are needed.

CONCLUSION

Our data demonstrate an important relationship between exposure to a single painful procedure and oxidative stress. Because neonates are exposed to many painful procedures during hospitalization, it is important to further examine the effect of single, multiple as well as accumulated TDPs in a randomized clinical trial. Mechanistic studies that will determine whether or not procedure-related increases in oxidative stress exacerbate pre-existing pathological conditions or trigger development of new abnormalities would provide additional insight.

Perspective.

This article presents data describing a significant relationship between physiological markers of neonatal pain and oxidative stress. The method described in this paper can potentially be used to assess the direct cellular effects of procedural pain as well the effectiveness of interventions performed to decrease pain.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Michael Lockwood for his assistance in subject recruitment. We thank all the NICU nurses, nurse practitioners and physicians for their assistance with study procedures.

Abbreviations

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- AMP

adenosine monophosphate

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- FIO2

fraction of inspired oxygen

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- NICU

neonatal intensive care unit

- NO•

nitric oxide

- ONOO−

peroxynitrite

- PIPP

Premature Infant Pain Profile

- SNAPPE-II

Score of Neonatal Acute Physiology Perinatal Extension II

- TDP

tissue-damaging procedures

- XDH

xanthine dehydrogenase

- XO

xanthine oxidase

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: This work is funded by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NR010407). We have no conflict of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Acharya AB, Annamali S, Taub NA, Field D. Oral sucrose analgesia for preterm infant venepuncture. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F17–18. doi: 10.1136/fn.89.1.F17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akman I, Ozek E, Bilgen H, Ozdogan T, Cebeci D. Sweet solutions and pacifiers for pain relief in newborn infants. J Pain. 2002;3:199–202. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.122943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anand KJ, Hall RW, Desai N, Shephard B, Bergqvist LL, Young TE, Boyle EM, Carbajal R, Bhutani VK, Moore MB, Kronsberg SS, Barton BA. Effects of morphine analgesia in ventilated preterm neonates: primary outcomes from the NEOPAIN randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1673–1682. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16251-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anand KJS, Sippell WG, Green AA. RANDOMISED TRIAL OF FENTANYL ANAESTHESIA IN PRETERM BABIES UNDERGOING SURGERY: EFFECTS ON THE STRESS RESPONSE. The Lancet. 1987;329:243–248. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballantyne M, Stevens B, McAllister M, Dionne K, Jack A. Validation of the premature infant pain profile in the clinical setting. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:297–303. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199912000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baouali AB, Aube H, Maupoil V, Blettery B, Rochette L. Plasma lipid peroxidation in critically ill patients: Importance of mechanical ventilation. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1994;16:223–227. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer K, Ketteler J, Hellwig M, Laurenz M, Versmold H. Oral glucose before venepuncture relieves neonates of pain, but stress is still evidenced by increase in oxygen consumption, energy expenditure, and heart rate. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:695–700. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000113768.50419.CD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellieni CV, Iantorno L, Perrone S, Rodriguez A, Longini M, Capitani S, Buonocore G. Even routine painful procedures can be harmful for the newborn. Pain. 2009;147:128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyer K, Johnston C, Walker CD, Filion F, Sherrard A. Does sucrose analgesia promote physiologic stability in preterm neonates? Biol Neonate. 2004;85:26–31. doi: 10.1159/000074954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buonocore G, Perrone S, Tataranno ML. Oxygen toxicity: chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2010;15:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calderon TC, Wu W, Rawson RA, Sakala EP, Sowers LC, Boskovic DS, Angeles DM. Effect of mode of birth on purine and malondialdehyde in umbilical arterial plasma in normal term newborns. J Perinatol. 2008;28:475–481. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbajal R, Lenclen R, Jugie M, Paupe A, Barton BA, Anand KJ. Morphine does not provide adequate analgesia for acute procedural pain among preterm neonates. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1494–1500. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carbajal R, Rousset A, Danan C, Coquery S, Nolent P, Ducrocq S, Saizou C, Lapillonne A, Granier M, Durand P, Lenclen R, Coursol A, Hubert P, de Saint Blanquat L, Boelle PY, Annequin D, Cimerman P, Anand KJ, Breart G. Epidemiology and treatment of painful procedures in neonates in intensive care units. JAMA. 2008;300:60–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Celebi H, Bozkirli F, Gunaydin B, Bilgihan A. Effect of high-dose lidocaine treatment on superoxide dismutase and malon dialdehyde levels in seven diabetic patients. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000;25:279–282. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(00)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi CH, Shiesh SC, Lin XZ. Total antioxidant capacity and malondialdehyde in acute abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:79–82. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2002.30102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chwals WJ. Energy expenditure in critically ill infants*. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2008;9:121–122. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000298659.51470.CB. 110.1097/1001.PCC.0000298659.0000251470.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cighetti G, Allevi P, Anastasia L, Bortone L, Paroni R. Use of methyl malondialdehyde as an internal standard for malondialdehyde detection: validation by isotope-dilution gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2002;48:2266–2269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danford DA, Miske S, Headley J, Nelson RM. Effects of routine care procedures on transcutaneous oxygen in neonates: a quantitative approach. Arch Dis Child. 1983;58:20–23. doi: 10.1136/adc.58.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dikensoy E, Balat O, Pence S, Balat A, Cekmen M, Yurekli M. Malondialdehyde, nitric oxide and adrenomedullin levels in patients with primary dysmenorrhea. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34:1049–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Sayed MF, Taddio A, Fallah S, De Silva N, Moore AM. Safety profile of morphine following surgery in neonates. J Perinatol. 2007;27:444–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fellman V, Raivio KO. Reperfusion Injury as the Mechanism of Brain Damage after Perinatal Asphyxia. Pediatric Research. 1997;41:599–606. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199705000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoehn T, Janssen S, Mani AR, Brauers G, Moore KP, Schadewaldt P, Mayatepek E. Urinary Excretion of the Nitrotyrosine Metabolite 3-Nitro-4-Hydroxyphenylacetic Acid in Preterm and Term Infants. Neonatology. 2008;93:73–76. doi: 10.1159/000106783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horton JW, Walker PB. Oxygen radicals, lipid peroxidation, and permeability changes after intestinal ischemia and reperfusion. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:1515–1520. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson MA, Tekkanat K, Schmaltz SP, Fox IH. Adenosine triphosphate turnover in humans. Decreased degradation during relative hyperphosphatemia. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:990–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI114263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapoor K, Basu S, Das BK, Bhatia BD. Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidants in Neonatal Septicemia. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2006;52:372–375. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fml013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Pant P, Basu S, Rao GR, Khanna HD. Oxidative stress in neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. J Trop Pediatr. 2007;53:69–71. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fml060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leef KH. Evidence-based review of oral sucrose administration to decrease the pain response in newborn infants. Neonatal Netw. 2006;25:275–284. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.25.4.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathew PJ, Mathew JL. Assessment and management of pain in infants. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:438–443. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.934.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nair V, Vietti DE, Cooper CS. Degenerative chemistry of malondialdehyde. Structure, stereochemistry, and kinetics of formation of enaminals from reaction with amino acids. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1981;103:3030–3036. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paller MS, Hoidal JR, Ferris TF. Oxygen free radicals in ischemic acute renal failure in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:1156–1164. doi: 10.1172/JCI111524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paroni R, Fermo I, Cighetti G. Validation of methyl malondialdehyde as internal standard for malondialdehyde detection by capillary electrophoresis. Anal Biochem. 2002;307:92–98. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plank MS, Boskovic DS, Tagge E, Chrisler J, Slater L, Angeles KR, Angeles DM. An animal model for measuring the effect of common NICU procedures on ATP metabolism. Biol Res Nurs. 2011;13:283–288. doi: 10.1177/1099800411400407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polin RF, William, Abman Steven. Fetal and Neonatal Physiology. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranger M, Johnston CC, Anand KJ. Current controversies regarding pain assessment in neonates. Semin Perinatol. 2007;31:283–288. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodríguez de Sotillo D, Velly AM, Hadley M, Fricton JR. Evidence of oxidative stress in temporomandibular disorders: a pilot study. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation no-no. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2011.02216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rokyta R, Yamamotova A, Sulc R, Trefil L, Racek J, Treska V. Assessment of biochemical markers in patients with pain of vascular origin. Clin Exp Med. 2008;8:199–206. doi: 10.1007/s10238-008-0001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saugstad OD. Role of xanthine oxidase and its inhibitor in hypoxia: reoxygenation injury. Pediatrics. 1996;98:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siciarz A, Weinberger B, Witz G, Hiatt M, Hegyi T. Urinary thiobarbituric acid-reacting substances as potential biomarkers of intrauterine hypoxia. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:718–722. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.6.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Speidel BD. Adverse effects of routine procedures on preterm infants. Lancet. 1978;1:864–866. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevens B, Johnston C, Petryshen P, Taddio A. Premature Infant Pain Profile: development and initial validation. Clin J Pain. 1996;12:13–22. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walden M, Carrier C. The ten commandments of pain assessment and management in preterm neonates. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2009;21:235–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wayenberg JL, Cavedon C, Ghaddhab C, Lefèvre N, Bottari SP. Early Transient Hypoglycemia Is Associated with Increased Albumin Nitration in the Preterm Infant. Neonatology. 2011;100:387–397. doi: 10.1159/000326936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeh ML, Chen HH, So EC, Liu CF. A study of serum malondialdehyde and interleukin-6 levels in young women with dysmenorrhea in Taiwan. Life Sci. 2004;75:669–673. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshikawa T, Oyamada H, Ichikawa H, Naito Y, Ueda S, Tainaka K, Takemura T, Tanigawa T, Sugino S, Kondo M. Role of active oxygen species and lipid peroxidation in liver injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1990;87:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]