Abstract

In a previous vaccine study, we reported significant and apparently sterilizing immunity to high-dose, mucosal, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) quasispecies challenge (27). The vaccine consisted of vectors based on vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) expressing simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) gag and env genes, a boost with propagating replicon particles expressing the same SIV genes, and a second boost with VSV-based vectors. Concurrent with that published study we had a parallel group of macaques given the same doses of vaccine vectors, but in addition, we included a third VSV vector expressing rhesus macaque GM-CSF in the priming immunization only. We report here that addition of the vector expressing GM-CSF did not enhance CD8 T cell or antibody responses to SIV antigens, and almost completely abolished the vaccine protection against high-dose mucosal challenge with SIV. Expression of GM-CSF may have limited vector replication excessively in the macaque model. Our results suggest caution in the use of GM-CSF as a vaccine adjuvant, especially when expressed by a viral vector. Combining vaccine group animals from this study and the previous study we found that there was a marginal but significant positive correlation between the neutralizing antibody to a neutralization resistant SIV Env and protection from infection.

INTRODUCTION

Vaccine vectors based on recombinant, attenuated vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) have been used to generate experim ental vaccines against infection or disease caused by multiple viral and bacterial pathogens (3, 5-7, 11, 23, 29). HIV vaccine clinical trials have been initiated recently (HVTN 090, http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01438606) with live, attenuated VSV vaccine vectors (8).

Previous studies showed that a VSV recombinant expressing murine granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) from the first position of the VSV genome was highly attenuated for replication in mice, yet it promoted antibody and primary CD8 T cell responses equivalent to those generated by a non-attenuated control VSV expressing EGFP. In addition, expression of GM-CSF induced enhanced CD8 memory T cells to the VSV nucleocapsid protein when compared to the control vector (22).

GM-CSF is a cytokine responsible for recruitment, activation, and maturation of antigen presenting cells (20). GM-CSF has been used extensively as an adjuvant in plasmid DNA immunizations where it has generally been shown to enhance humoral and cellular immune responses (1, 2, 15, 16). However, some studies have indicated that GM-CSF can reduce immune responses (17, 33, 34). Because non-human primate studies are often better than mouse studies at predicting vaccine efficacy in humans, we tested the effects of GM-CSF expressed from a VSV vector in an SIV vaccine study done in parallel with our previous published study (27). In the previous study we obtained apparently sterilizing immunity in 4/ 6 vaccinated animals and rapid control of SIV replication in the 2/ 6 vaccinees that became infected. In contrast, the 6 control animals were all infected by the high dose mucosal challenge, had higher peak viral loads than the 2 vaccinees that became infected, and three of the controls developed AIDS. In the study reported here we found that GM-CSF expressed during the priming vaccination almost completely eliminated vaccine protection, with only one animal showing apparently sterilizing protection. The outcomes in the remaining animals were not significantly different from those of the controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vaccine vector construction

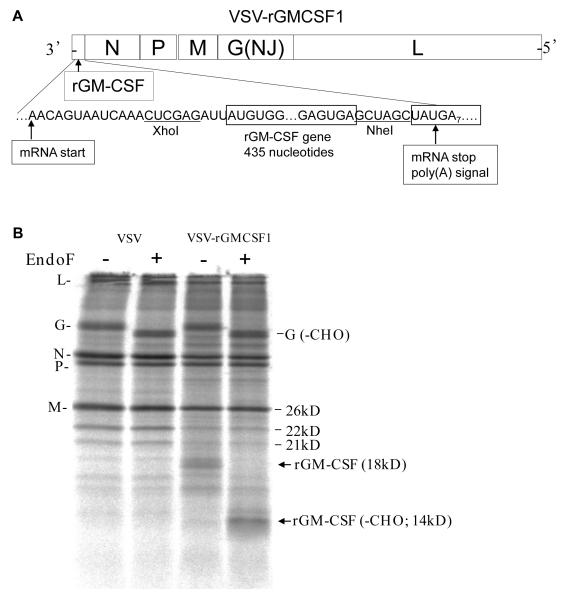

The rhesus GM-CSF gene was amplified by PCR from the plasmid (pGEM-5Zf RSt GM-CSF) provided by Dr. Francois Villinger (Emory University). The gene was between the Xho I and Nhe I sites of a first position VSV expression vector having the VSV NJG gene in place of the Indiana serotype vector (26). The plasmid, designated pVSVNJG-rGMCSF1, was used to recover the virus designated VSVNJG-rGMCSF1 and diagrammed in Fig. 1A. The construction, recovery, and preparation of all other vaccine vector stocks have been described previously (27).

FIG 1.

VSV-rGMCSF1 genome diagram and protein expression. (A) A diagram showing the gene order of the recombinant in the 3′-5′ orientation on the negative strand RNA. Sequences are shown in the positive (antigenome) sense for clarity. The mRNA start and stop (poly (A)) signals are indicated. Restriction sites used for cloning the rGM-CSF gene are indicated also. (B) An autoradiogram of SDS-PAGE of lysates of BHK cells infected with VSV or VSV-rGMCSF1 and labeled with [35S]-methionine. Cell lysates were left untreated (−) or treated with endoglycosidase-F (+). Positions of VSV proteins and the N - glycosylated and de-glycosylated forms of rGMCSF are indicated. The mature rGM-CSF is 18 kilodaltons (kD) including its two N -linked glycans was readily detected in cells infected with the VSV-rGMCSF1 recombinant. Digestion with endoglycosidase F (EndoF) to remove N -linked glycans resulted in the disappearance of the 18 kD band and the appearance of a new band with a faster mobility consistent with the removal of the two glycans.

Vaccinations

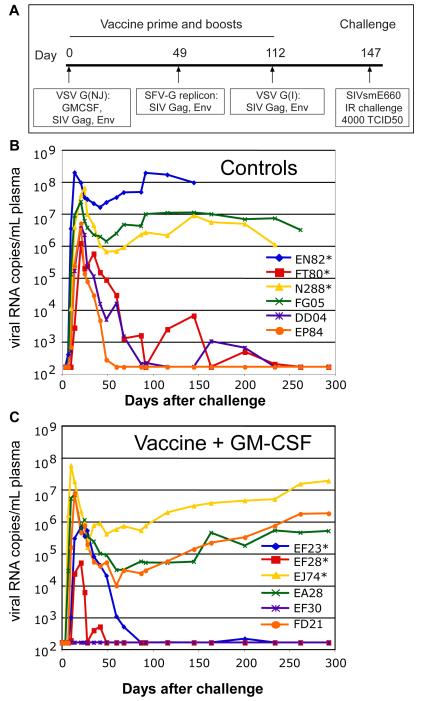

Vaccinations followed the schedule shown in Fig. 2A. The vaccine+ GM-CSF group described here was vaccinated and challenged concurrently with previously published vaccine and control groups. Doses of vaccine viruses and immunization routes were the same for the published vaccine study (27). The VSV-NJG vector prime consisted of 1×108 plaque forming units (pfu) of each of the VSVNJG-E660Gag and VSVNJG-E660EnvG vectors, and an additional 1×107 pfu of the VSVNJG-rGMCSF1 vector in a total of 1ml. Viruses were co-administered intranasally (0.4ml) and intramuscularly (0.6ml). The SFVG replicon particle boost was delivered by intramuscular injection only. Each animal received 1×106 infectious units (i.u.) of both SFVG-Gag and SFVG-EnvG. A second boost of a total of 108 pfu of each of VSV-E660Gag and VSV–E660EnvG vectors (G Indiana serotype) in 1 ml was delivered IN (0.4ml) and IM (0.6ml) as above.

FIG 2.

VSV vaccination schedule and viral load data. (A) Schedule for vaccination and challenge with SIVsmE660. (B) Plasma viral loads in six control animals. (C) Plasma viral loads in the vaccinated animals primed with VSV-rGMCSF1, VSV-Gag and VSV-Env. Asterisks in panels B and C indicate the MamuA*01+ animals. Plasma viral loads were quantified by branched DNA (bDNA) analysis on serum samples at Siemens Diagnostics, Clinical Laboratory (Berkeley, CA). The TRIM5α genotypes for each animal were as follows: EF23 (CypA/CypA), EF28 (TFP/TFP), EJ74 (TFP/Q), EA28 (Q/CypA), EF30 (TFP/TFP), FD21 (Q/Q). (D) Average plasma viral loads for the previously reported vaccine (blue) and control groups (green) and the vaccine+GMCSF (red). Error bars indicate +/ − 1 standard deviation.

Immunological assays

Virus neutralization assays, ELISPOT, and flow cytometry assays were performed as described previously (27). GM-CSF production was quantified in a GM-CSF ELISA assay (Cell Sciences; Canton, MA). Function of the GM-CSF (13) was measured by stimulation of growth of TF-1 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Data were analyzed and plotted using Prism software, version 4.0b (GraphPad Software; San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

High-level expression of rhesus GM-CSF in a VSV recombinant

To derive a VSV recombinant that would express rhesus macaque GM-CSF as a potential vaccine adjuvant, we cloned the rhesus macaque GM-CSF gene into a plasmid that allowed virus recovery and expression of the gene from the first (most highly expressed) position of the VSV genome. Fig. 1A shows a diagram of the genome of the recombinant virus expressing rhesus GM-CSF.

Expression of glycoslyated GM-CSF of the correct size was verified by infecting BHK cells with wild-type or recombinant virus, labeling cells with [35S]-methionine, and fractionating the labeled cell lysate by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1B). Elisa assays showed that 2 × 107 BHK cells infected with the VSVNJG-rGMCSF1 vector secreted 26 μg rhesus GM-CSF into the 10 ml of medium after 24 hours. The VSV encoded GM-CSF was biologically active in promoting the survival and growth of a human TF-1 cell line (13).

Study design

In this study two groups of six rhesus macaques were vaccinated, boosted, and challenged as indicated in Fig. 2A. Each group included three animals (marked with asterisks) carrying the MamuA*01 MHC I allele, so that Gag-specific CTL responses could be quantified by MHC I tetramer analysis. One animal in each group also carried the B*17 MHC allele (EA28, EP84). Both the A*01 and B*17 alleles have been associated with better control of SIVmac239/ 251 replication through CTL recognition of immunodominant epitopes (9, 21).

The vaccine group animals were primed with a mixture of VSV-NJG vectors encoding SIVsmE660 Gag and Env sequences generated from the E660 quasispecies, as in the vaccine group described previously (27). However, in addition to these vectors, a VSV vector expressing rhesus GM-CSF was included in the priming immunization only. At 49 days post-prime, the animals were boosted intramuscularly with SFVG propagating replicons expressing E660 Gag and EnvG genes. This was followed by a second boost on day 112 with VSV vectors that expressed the same genes. On day 147, all animals received a high - dose intrarectal challenge with SIVsmE660 (TCID50=4000). The only difference in vaccine regimen between the vaccine group reported here and the previously published vaccine group (27) was the addition of the VSV vector expressing rhesus GM-CSF vector during the prime only. The control animals were the same animals described previously (27) and received VSV vectors expressing an unrelated influenza antigen.

Plasma viral loads following SIVsmE660 challenge

As shown in Fig. 2B, all of the control animals became infected and three (EN82, FG05, N288) developed high viral loads and setpoints. The remaining three animals controlled viral loads to below detection between 60 and 225 days post challenge. In the GM-CSF vaccine group (Fig. 2C) only one animal (EF30) appeared to be completely protected from infection, three had high peak loads and high set points (EJ74, FD21, EA28), and the remaining two animals controlled virus load to below detection between 50 and 90 days post-challenge (EF23, EF28). There was no statistically significant difference in peak viral loads between the vaccine and control groups. This is in contrast to the previously published vaccine group, which lacked VSV vectored GM-CSF during its priming vaccination. In that group, four out of six animals were protected from infection, and the two that were infected rapidly controlled the infection (27). Average plasma viral loads are shown for all three groups in Fig. 2D.

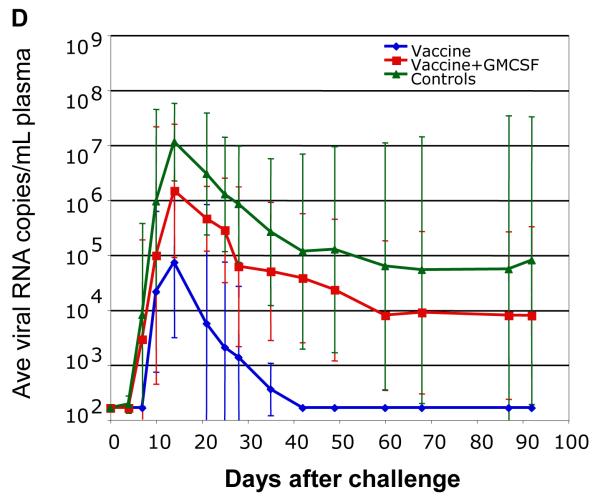

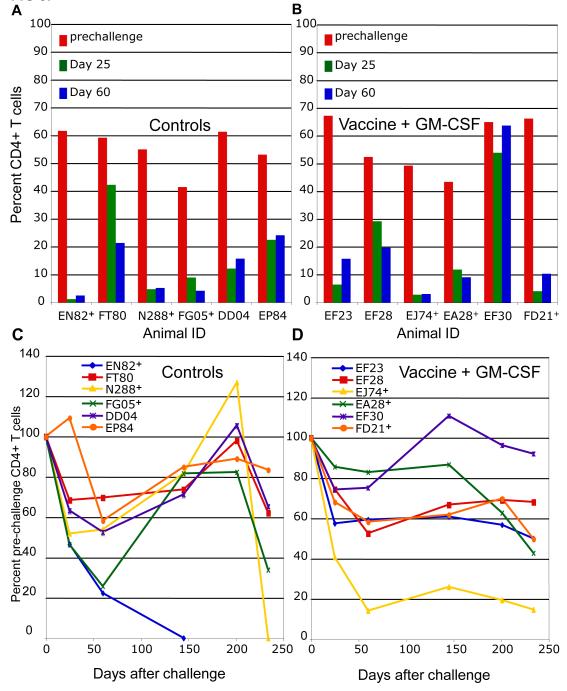

Depletion of CD4+ T cells in the gut after SIVsmE660 challenge

Rapid depletion of memory CD4+ T cells from the gut lamina propria occurs soon after infection by SIV or HIV (28, 31). To examine the effects of the SIVsmE660 challenge on the gut CD4+ T cells in vaccine and control groups, we compared the percentages of CD4+ T cells isolated from intestinal biopsies on the day of challenge (day 0) to those 25 and 60 days following challenge. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, a marked reduction in gut CD4+ T cells was seen in all infected animals from both the control and vaccine groups. The one protected animal from the vaccine group (EF30) showed no significant reduction in gut CD4+ T cells, and mirrored what was seen for the four protected animals from the previously published vaccine group (27).

FIG 3.

Gut and peripheral blood CD4+ T cells in control and vaccine group animals. The percentage of CD3+ gut lymphocytes that were CD4+ on the day of challenge and at 25 and 60 days postchallenge are shown for the (A) control and (B) vaccine+GM-CSF groups. Blood CD4+ T cell counts are expressed as a percentage of the average pre-challenge CD4+ T cell counts for the for the control (C) and vaccine+GM-CSF (D) groups. Animals in each group with the highest viral loads are indicated by the + symbol.

For both infected controls and vaccinees, the decline in peripheral blood CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3C and D) progressed less rapidly. The vaccinee with highest viral load (EJ74) also showed the fastest depletion of CD4+ T cells from the blood. The lone protected animal, EF30, maintained its initial level of CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood.

Neutralizing antibody production

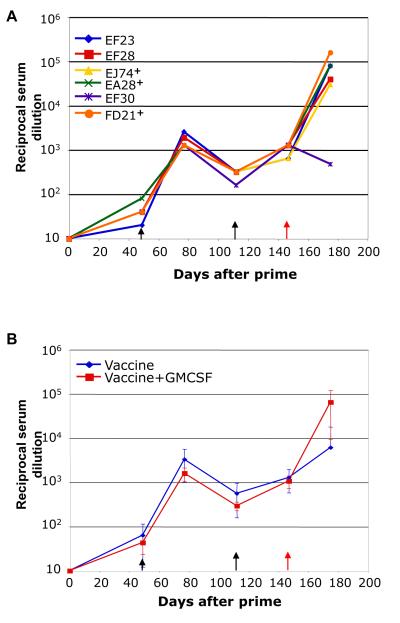

We examined the ability of the addition of VSV vectored GM-CSF to the vaccine prime to elicit neutralizing antibodies against SIVsmE660 envelopes. We first tested for the ability of serum antibodies to neutralize a VSVΔG-EnvG-GFP recombinant that expresses the SIVsmE660 envelope present in the vaccine. Results from serum collected pre- and post-challenge are shown in Fig. 4A. Low titers of neutralizing antibody were detected against the vaccine envelope after the prime in all animals. Animals showed a greater than ten-fold increase in neutralizing titers after the initial SFVG vector boost, and a small but detectable increase in these titers was seen after the second boost with VSV vectors. All animals had serum neutralizing antibodies to the vaccine envelope at the time of challenge. At 28 days after the challenge, all five animals that were infected showed an anamnestic antibody response. In contrast, the one protected animal, EF30, showed a decrease in neutralizing antibody titer following challenge, consistent with lack of infection. Our previously reported vaccine group, which did not receive GM-CSF at the time of prime, developed slightly higher average titers of neutralizing antibodies to the envelope present in the vaccine, although these differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Neutralizing antibody responses in the vaccine group animals. nAb to the EnvG protein present in the vaccine using was determined using a VSVΔGEnvG-GFP surrogate virus described previously (25). (A) Serum nAb titers are shown for the vaccine+GM-CSF group animals on day of first vaccination (0) and at the indicated times thereafter. Days of boosts and of the SIVsmE660 challenge are indicated by black and red arrows, respectively. Animals with the highest viral loads are designated by +. (B) Comparison of average nAb titers for the vaccine+GM-CSF group (red) and the previously reported vaccine group without GM-CSF (blue) is shown in Panel B. Neutralization was calculated as a function of reductions in luciferase reporter gene expression after a single round of infection in TZM-bl cells (19).

Similar to what we reported previously for the vaccine group without GM-CSF, no neutralizing antibody against either the SIVsmE660 quasispecies, or to the two cloned tier 2 E660 Envs tested, CR54-PK-2A5 and BR-CG7V.IR (12), was detectable in the serum at the day of challenge or at earlier times using a serum dilution of 1:20.

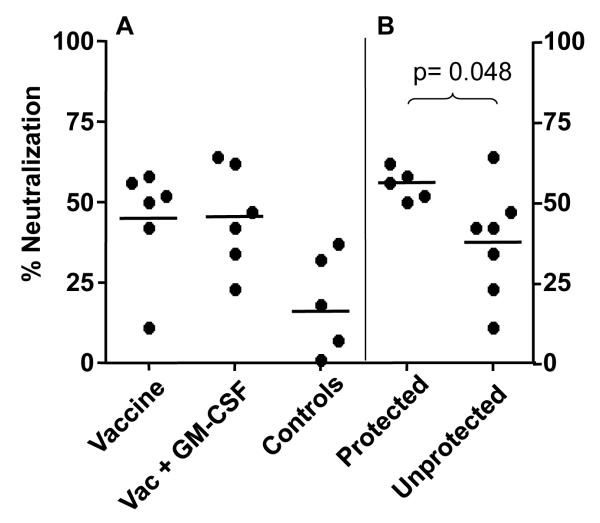

To determine if any significant nAb could be detected in serum from animals in this and the prior group (27) at a lower dilution, we tested serum samples at a dilution of 1:10. At this low dilution, some neutralization against SIVsmE660 CR54-PK-2A5 (12), a neutralization resistant tier 2 envelope, w as seen in vaccinated animals (Fig. 5A) and it was significantly higher than the background neutralization seen in serum from control animals. However, there was no significant difference between the vaccine and vaccine plus GM-CSF groups.

FIG 5.

Percent neutralization of SIVsmE660/ CR54-PK-2A5 in TZM-bl cells by serum from vaccinated and control animals at low dilution. (A) Comparison of nAb in the vaccine, vaccine+GM-CSF, and control groups. (B) Comparison of nAb titers between the five protected animals and the seven unprotected animals in both vaccine groups. The final dilution of serum was 1:10. The average percent neutralization is represented by the black horizontal bar for each group. Percent neutralization was calculated as the reduction in RLU by post-immunization serum relative to the corresponding pre-immunization serum sample for each animal. A significant difference in neutralization titers was seen between protected versus unprotected animals (B, p=0.048).

We next asked if there was a significant difference in nAb (1:10 serum dilution) to the CR54-PK-2A5 Env at time of challenge between the five animals protected from challenge (four from the previous study and one from this study), and the seven animals that were not protected (two from the previous study and five from this study). When this comparison was made the mean nAb levels were found to be significantly higher (p=0.048, Mann-Whitney test) in the protected animals (Fig. 5B) when compared to unprotected animals.

CD8 T cell responses

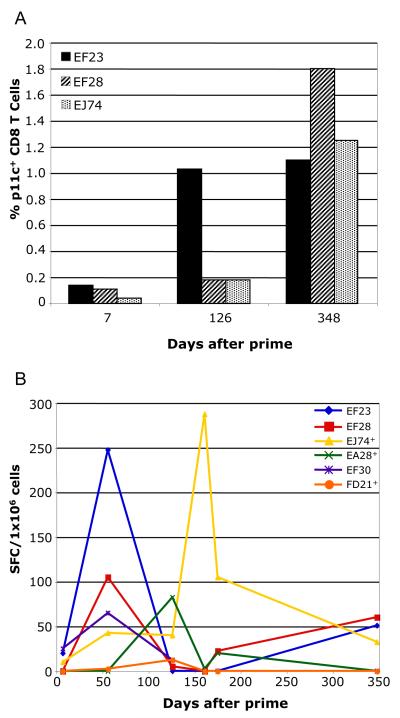

Based on published experiments in mice (22) we had expected to see an increase in CD8+ memory T cells in macaques primed in the presence of GM-CSF expression compared to those primed in the absence of GM-CSF expression. To examine the CD8+ T cell responses after prime, boost, and challenge, we quantified the number of Gag specific CD8+ T cells by tetramer analysis (p11c epitope) and tested total Gag functional responses by IFN -γ ELISpot. As shown in Fig. 6A, two of the three Mamu A*01 animals (EF28 and EJ74) showed only small increases in gag tetramer+ CD8+ T cells after the second boost while the third animal (EF23) showed a larger increase. These responses were no greater than what we had seen previously in animals primed in the absence of GM-CSF expression (27). All three Mamu A*01 animals became infected and maintained high levels of p11c+CD8+ T cells for longer than six months after challenge (day 348).

FIG 6.

Tetramer and ELISpot analysis of cellular immune responses in PBMCs from vaccine+GM-CSF group animals. (A) Tetramer staining of CD8+ T cells binding the immunodominant gag p11c epitope (Mamu A*01 animals only). Data are presented as a percentage of CD3+CD8+ cells that are also p11c tetramer+. (B) IFN-γ ELISpot assay of SIV Gag specific responses for all animals in the vaccine+GM-CSF group. Data are represented as spot forming cells (SFC) per 1×106 cells. Animals designated + had the highest viral load.

Functional cellular immune responses against Gag antigen measured by IFN-γ ELISpot were determined for all vaccinated animals (Fig. 6B). The responses were generally weak and variable among the animals. The one animal that was protected from infection (EF30), made only a very low response to Gag that was detectable only at one time point, one week after the first boost (Fig. 6B). Animal EF23 had the highest percentage of p11c+CD8+ T cells prior to challenge (Fig. 6A), and also had the highest peak level of IFN -γ producing cells. After challenge, the animal with the highest load, EJ74, showed a large increase in IFN -γ producing cells responding to Gag antigen. This response decreased at later times. By day 348 post-challenge, all animals had low or undetectable responses to Gag, even those that had high levels of Gag tetramer positive cells. These results suggest that the tetramer+ T cells were non-functional at later times, presumably due to continuing antigen stimulation leading to exhaustion (14).

DISCUSSION

Previous work from our laboratory showed that expression of a murine GM-CSF gene from a VSV recombinant resulted in decreased vector replication in mice, enhanced recruitment of macrophages to the lung, and increased VSV-specific memory CD8+ T cell population in the lungs and spleen (22). In the present study we had hoped to see a similar enhancement of immune responses to SIV proteins in rhesus macaques by including a VSV vector expressing rhesus GM-CSF along with VSV vectors expressing SIV Env and Gag proteins in a priming immunization. Based on experiments involving use of GM-CSF as an SIV vaccine adjuvant in macaques (15, 16), we also hoped to see enhanced antibody responses to SIV Env. However, we observed lower antibody responses, weak cellular immune responses, and decreased protection against SIV challenge compared to a parallel group of animals given the identical vaccine and boost regimen but without VSV expressing GM-CSF in the priming immunization (27).

While a reduction in average plasma viral loads was seen between the vaccine+GM-CSF group and the controls, the difference was not statistically significant. The plasma viral loads among infected animals in the GM-CSF group largely mirrored the control group, with three animals failing to control, and two that controlled the SIVsmE660 infection. Only one animal in this vaccine group resisted infection (Fig. 2).

We also did not detect improved humoral or cellular immune responses in the GM-CSF group. Average pre-challenge neutralizing antibody titers were slightly lower in the vaccine group with GM-CSF. Post-challenge anamnestic responses were seen only in those animals that became infected, Fig. 4 and (27). GM-CSF also did not enhance IFN-γ responses to Gag (Fig. 6b) or Env (data not shown). We also did not see significant differences in ELISA titers to SIV Env between the two vaccine groups following the first or second boost (data not shown). In both vaccine groups the animals that were protected from infection showed only weak cellular immune response in PBMCs at times shortly after challenge. This result suggests that cellular immunity was not important for protection. However there is a possibility that mucosal CTL could be providing protection even in the absence of significant responses in PBMCs.

Although we observed high titer serum nAbs to a tier 1 SIVsmE660 envelope (E660.11) in the six vaccinees from this study and the six from the previous study (27), we did not see a correlation between protection and nAb titer. However, when we measured serum nAb to a tier 2 SIVsmE660 Env/ CR54-PK-2A5 (12) at low dilution, we found a marginally significant positive correlation (P< 0.05) of nAb titer with protection. Similar to what we observed here, a recent study reported that neutralization of the CR54-PK-2A5 Env correlated positively with protection, but only in the subgroup of animals that lacked the MHC I Mamu A*01 allele (18). Of the twelve vaccinees in our two studies, six were MamuA*01-positive, and six were MamuA*01-negative, and it was not necessary to subgroup them to see the correlation.

In this study we did not have mucosal wash sample from times prior to challenge. In future studies it will be important to examine the SIV Env binding and potential neutralizing antibodies present in the rectal mucosa.

The TRIM5α gene can affect the viral loads that develop in macaques infected with SIVsmE660 (24). In an extensive study of TRIM5α and its possible role in inhibiting infection by SIVsmE660, only one combination of TRIM5 alleles (TRIM5αTFP/ CypA) was associated with delayed acquisition SIVsmE660 infection in repeated low-dose challenges (24). We determined the TRIM5α genotypes for the animals in this group as well as the previous vaccine and control groups (27). None of the animals in this (Fig. 2, legend) or the previously published vaccine group had the TRIM5αTFP/ CypA genotype. There are conflicting reports on whether TRIM5α can affect the rate of acquisition of SIVsmE660 in low dose challenge of vaccinated animals (15, 18).

Why did GM-CSF expression do the opposite of what we expected? One possibility is that the viral vector expressed excessive amounts of GM-CSF that caused immune suppression. Suppression of immune responses by excessive GM-CSF has been reported (10, 17). Based on our murine studies, this possibility seems unlikely because the amount of virus expressing GM-CSF was only 5% of the total VSV vector dose given to the macaques in the priming vaccination, while in the mouse studies, all of the recombinants expressed GM-CSF (22). A possibility that we consider more likely is that the local expression of GM-CSF led to rapid clearance of the vaccine viruses by rapidly recruiting macrophages and other cells to the viral replication site (22). This situation was evident in our previous mouse studies (22), where we saw rapid recruitment of macrophages to the lung, and reductions in GM-CSF vector replication greater than 100-fold. The reduced replication was apparently compensated for by increased immunogenicity. In the macaques, the restriction of vaccine vector replication caused by GM-CSF may have been more severe, resulting in weaker immune responses. Alternatively, the expression of GM-CSF during the prime may have had more direct effects on T-cell function and survival. An earlier study employing a recombinant respiratory syncytical virus vector showed that expression of murine GM-CSF led to a reduction in CD8+ T cell responses in mice, possibly due to reduced replication of the viral vector (4). It was also reported recently that expression of murine GM-CSF by a rabies virus vector caused a reduction in CD8+ T cell responses to HIV Gag in vaccinated mice and this effect was abrogated by administering an anti-GM-CSF antibody (32).

Although there is an extensive literature on the use of GM-CSF as a vaccine adjuvant (30), there is little information available on using viral vectors to deliver GM-CSF in non-human primate models. Our study showed that a VSV-based delivery system for GM-CSF is not effective at enhancing immune responses or vaccine effectiveness, and suggests caution in the future use of replicating vectors expressing GM-CSF.

Highlights.

Expression of VSV encoded GMCSF during prime did not enhance immune responses.

GMCSF reduced the level of protection against subsequent SIVsmE660 challenge.

Serum neutralizing antibody titers toward Env isolate correlated with protection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Philip Johnson for supplying of the SIVsmE660 challenge stock and for helpful suggestions. We also thank Dr. Welkin Johnson for TRIM5α genotyping of the animals, Drs. Gunilla Karlsson and Peter Lilejstrom for providing the pBK-T-SFV vector, and Dr. Robert Doms for providing vaccinia virus recombinants expressing SIV Env protein. This work was supported by NIH grants AI45510 and AI-40357, the Tulane National Primate Research Center base grant RR000164, and NIAID contract AI8534.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ahlers JD, Dunlop N, Alling DW, Nara PL, Berzofsky JA. Cytokine-in-adjuvant steering of the immune response phenotype to HIV-1 vaccine constructs: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and TNF-alpha synergize with IL-12 to enhance induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;158:3947–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowne WB, Wolchok JD, Hawkins WG, Srinivasan R, Gregor P, Blachere NE, Moroi Y, Engelhorn ME, Houghton AN, Lewis JJ. Injection of DNA encoding granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor recruits dendritic cells for immune adjuvant effects. Cytokines Cell Mol Ther. 1999;5:217–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandsma JL, Shylankevich M, Su Y, Roberts A, Rose JK, Zelterman D, Buonocore L. Vesicular stomatitis virus-based therapeutic vaccination targeted to the E1, E2, E6, and E7 proteins of cottontail rabbit papillomavirus. J Virol. 2007;81:5749–58. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02835-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bukreyev A, Belyakov IM, Berzofsky JA, Murphy BR, Collins PL. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor expressed by recombinant respiratory syncytial virus attenuates viral replication and increases the level of pulmonary antigen-presenting cells. J Virol. 2001;75:12128–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12128-12140.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chattopadhyay A, Park S, Delmas G, Suresh R, Senina S, Perlin DS, Rose JK. Single-dose, virus-vectored vaccine protection against Yersinia pestis challenge: CD4+ cells are required at the time of challenge for optimal protection. Vaccine. 2008;26:6329–37. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chattopadhyay A, Rose JK. Complementing defective viruses that express separate paramyxovirus glycoproteins provide a new vaccine vector approach. J Virol. 2011;85:2004–11. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01852-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cobleigh MA, Buonocore L, Uprichard SL, Rose JK, Robek MD. A vesicular stomatitis virus-based hepatitis B virus vaccine vector provides protection against challenge in a single dose. J Virol. 2010;84:7513–22. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00200-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper D, Wright KJ, Calderon PC, Guo M, Nasar F, Johnson JE, Coleman JW, Lee M, Kotash C, Yurgelonis I, Natuk RJ, Hendry RM, Udem SA, Clarke DK. Attenuation of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine vectors by gene translocations and g gene truncation reduces neurovirulence and enhances immunogenicity in mice. J Virol. 2008;82:207–19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01515-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans DT, Jing P, Allen TM, O’Connor DH, Horton H, Venham JE, Piekarczyk M, Dzuris J, Dykhuzen M, Mitchen J, Rudersdorf RA, Pauza CD, Sette A, Bontrop RE, DeMars R, Watkins DI. Definition of five new simian immunodeficiency virus cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes and their restricting major histocompatibility complex class I molecules: evidence for an influence on disease progression. J Virol. 2000;74:7400–10. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7400-7410.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faderl S, Harris D, Van Q, Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M, Estrov Z. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) induces antiapoptotic and proapoptotic signals in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2003;102:630–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geisbert TW, Feldmann H. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccines against ebola and marburg virus infections. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(Suppl 3):S1075–81. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keele BF, Li H, Learn GH, Hraber P, Giorgi EE, Grayson T, Sun C, Chen Y, Yeh WW, Letvin NL, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Haynes BF, Bhattacharya T, Perelson AS, Korber BT, Hahn BH, Shaw GM. Low-dose rectal inoculation of rhesus macaques by SIVsmE660 or SIVmac251 recapitulates human mucosal infection by HIV-1. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1117–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitamura T, Tange T, Terasawa T, Chiba S, Kuwaki T, Miyagawa K, Piao YF, Miyazono K, Urabe A, Takaku F. Establishment and characterization of a unique human cell line that proliferates dependently on GM-CSF, IL-3, or erythropoietin. J Cell Physiol. 1989;140:323–34. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041400219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kostense S, Vandenberghe K, Joling J, Van Baarle D, Nanlohy N, Manting E, Miedema F. Persistent numbers of tetramer+ CD8(+) T cells, but loss of interferon-gamma+ HIV-specific T cells during progression to AIDS. Blood. 2002;99:2505–11. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai L, Kwa S, Kozlowski PA, Montefiori DC, Ferrari G, Johnson WE, Hirsch V, Villinger F, Chennareddi L, Earl PL, Moss B, Amara RR, Robinson HL. Prevention of infection by a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor co-expressing DNA/modified vaccinia Ankara simian immunodeficiency virus vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:164–73. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai L, Vodros D, Kozlowski PA, Montefiori DC, Wilson RL, Akerstrom VL, Chennareddi L, Yu T, Kannanganat S, Ofielu L, Villinger F, Wyatt LS, Moss B, Amara RR, Robinson HL. GM-CSF DNA: an adjuvant for higher avidity IgG, rectal IgA, and increased protection against the acute phase of a SHIV-89.6P challenge by a DNA/MVA immunodeficiency virus vaccine. Virology. 2007;369:153–67. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lechner MG, Liebertz DJ, Epstein AL. Characterization of cytokine-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells from normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:2273–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Letvin NL, Rao SS, Montefiori DC, Seaman MS, Sun Y, Lim SY, Yeh WW, Asmal M, Gelman RS, Shen L, Whitney JB, Seoighe C, Lacerda M, Keating S, Norris PJ, Hudgens MG, Gilbert PB, Buzby AP, Mach LV, Zhang J, Balachandran H, Shaw GM, Schmidt SD, Todd JP, Dodson A, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ. Immune and Genetic Correlates of Vaccine Protection Against Mucosal Infection by SIV in Monkeys. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:81ra36. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M, Gao F, Mascola JR, Stamatatos L, Polonis VR, Koutsoukos M, Voss G, Goepfert P, Gilbert P, Greene KM, Bilska M, Kothe DL, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Wei X, Decker JM, Hahn BH, Montefiori DC. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env clones from acute and early subtype B infections for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2005;79:10108–25. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10108-10125.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Min L, Mohammad Isa SA, Shuai W, Piang CB, Nih FW, Kotaka M, Ruedl C. Cutting edge: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor is the major CD8+ T cell-derived licensing factor for dendritic cell activation. J Immunol. 2010;184:4625–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connor DH, Mothe BR, Weinfurter JT, Fuenger S, Rehrauer WM, Jing P, Rudersdorf RR, Liebl ME, Krebs K, Vasquez J, Dodds E, Loffredo J, Martin S, McDermott AB, Allen TM, Wang C, Doxiadis GG, Montefiori DC, Hughes A, Burton DR, Allison DB, Wolinsky SM, Bontrop R, Picker LJ, Watkins DI. Major histocompatibility complex class I alleles associated with slow simian immunodeficiency virus disease progression bind epitopes recognized by dominant acute-phase cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte responses. J Virol. 2003;77:9029–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.9029-9040.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsburg E, Publicover J, Buonocore L, Poholek A, Robek M, Palin A, Rose JK. A vesicular stomatitis virus recombinant expressing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces enhanced T-cell responses and is highly attenuated for replication in animals. J Virol. 2005;79:15043–53. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15043-15053.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramsburg E, Rose NF, Marx PA, Mefford M, Nixon DF, Moretto WJ, Montefiori D, Earl P, Moss B, Rose JK. Highly effective control of an AIDS virus challenge in macaques by using vesicular stomatitis virus and modified vaccinia virus Ankara vaccine vectors in a single-boost protocol. J Virol. 2004;78:3930–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.3930-3940.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds MR, Sacha JB, Weiler AM, Borchardt GJ, Glidden CE, Sheppard NC, Norante FA, Castrovinci PA, Harris JJ, Robertson HT, Friedrich TC, McDermott AB, Wilson NA, Allison DB, Koff WC, Johnson WE, Watkins DI. The TRIM5{alpha} genotype of rhesus macaques affects acquisition of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsmE660 infection after repeated limiting-dose intrarectal challenge. J Virol. 2011;85:9637–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05074-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose NF, Marx PA, Luckay A, Nixon DF, Moretto WJ, Donahoe SM, Montefiori D, Roberts A, Buonocore L, Rose JK. An effective AIDS vaccine based on live attenuated vesicular stomatitis virus recombinants. Cell. 2001;106:539–49. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose NF, Roberts A, Buonocore L, Rose JK. Glycoprotein exchange vectors based on vesicular stomatitis virus allow effective boosting and generation of neutralizing antibodies to a primary isolate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2000;74:10903–10. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.10903-10910.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schell JB, Rose NF, Bahl K, Diller K, Buonocore L, Hunter M, Marx PA, Gambhira R, Tang H, Montefiori DC, Johnson WE, Rose JK. Significant protection against high-dose simian immunodeficiency virus challenge conferred by a new prime-boost vaccine regimen. J Virol. 2011;85:5764–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00342-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider T, Jahn HU, Schmidt W, Riecken EO, Zeitz M, Ullrich R, Berlin Diarrhea/Wasting Syndrome Study Group Loss of CD4 T lymphocytes in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is more pronounced in the duodenal mucosa than in the peripheral blood. Gut. 1995;37:524–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.4.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz JA, Buonocore L, Suguitan A, Jr., Hunter M, Marx PA, Subbarao K, Rose JK. Vesicular stomatitis virus-based H5N1 avian influenza vaccines induce potent cross-clade neutralizing antibodies in rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2011;85:4602–5. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02491-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toka FN, Pack CD, Rouse BT. Molecular adjuvants for mucosal immunity. Immunol Rev. 2004;199:100–12. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Shvetz DE, Pauley DR, Knight HL, Rosenzweig M, Johnson RP, Desrosiers RC, Lackner AA. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science. 1998;280:427–31. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wanjalla CN, Goldstein EF, Wirblich C, Schnell MJ. A role for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in the regulation of CD8(+) T cell responses to rabies virus. Virology. 2012;426:120–33. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wunderlich G, Moura IC, del Portillo HA. Genetic immunization of BALB/c mice with a plasmid bearing the gene coding for a hybrid merozoite surface protein 1-hepatitis B virus surface protein fusion protects mice against lethal Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi PC1 infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5839–45. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5839-5845.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xing Z, Tremblay GM, Sime PJ, Gauldie J. Overexpression of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces pulmonary granulation tissue formation and fibrosis by induction of transforming growth factor-beta 1 and myofibroblast accumulation. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:59–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]