Abstract

Renal epithelial cells from donor kidneys are susceptible to hypothermic preservation injury, which is attenuated when they over express the cytoskeletal linker protein ezrin (Tian, 2009). This study was designed to characterize the mechanisms of this protection. Renal epithelial cell lines were created from LLC-PK1 cells, which expressed mutant forms of ezrin with site directed alterations in membrane binding functionality. The study used cells expressing wild type ezrin, T567A, and T567D ezrin point mutants. The A and D mutants have constitutively inactive and active membrane binding conformations, respectively. Cells were cold stored (4°C) for 6–24 hrs and reperfused for 1 hr to simulate transplant preservation injury. Preservation injury was assessed by mitochondrial activity (WST-1) and LDH release. Cells expressing the active ezrin mutant (T567D) showed significantly less preservation injury compared to wild type or the inactive mutant (T567A), while ezrin-specific siRNA knockdown and the inactive mutant potentiated preservation injury. Ezrin was extracted and identified from purified mitochondria. Furthermore, isolated mitochondria specifically bound anti-ezrin antibodies, which were reversed with the addition of exogenous recombinant ezrin. Recombinant wild type ezrin significantly reduced the sensitivity of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) to calcium, suggesting ezrin may modify mitochondrial function. In conclusion, the cytoskeletal linker protein ezrin plays a significant role in hypothermic preservation injury in renal epithelia. The mechanisms appear dependent on the molecule’s open configuration (traditional linker functionality) and possibly a novel mitochondrial specific role, which may include modulation of mPTP function or calcium sensitivity.

Keywords: ERM Proteins, Kidney Donation, Mitochondria, mPTP

Introduction

Renal transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with end stage kidney failure. However, since the demand for donor kidneys outstrip the availability by 4 to 1, many remain on dialysis or die waiting (31). About half of transplanted kidneys derive from cadaver donors, which subject them to organ donation stress and preservation injury. This typically includes hypothermia, ischemia, and reperfusion injury that occurs during donation, storage, and at transplantation. In order to expand the donor pool to meet the increased demand, kidneys are being accepted from donors that were once considered unacceptable. These kidneys often experience warm ischemia before harvest and donor risk factors such as advanced age and chronic diseases. These additional risk factors potentiate the existing preservation injury (19; 29). This in turn increases the chances for the development of chronic graft failure, late graft loss, and reduces the life expectancy of the graft, which puts further pressure on organ availability as these patients are re-transplanted or go back on dialysis (28; 29; 35). Therefore, significant advancements in organ preservation are needed to expand the donor pool to meet the demand (12; 20).

While multiple factors are involved in renal preservation injury including tissue edema, ATP depletion, calcium, oxidative stress, inflammation, mediators, etc. (5; 11; 21; 22; 30; 33); interventions directed at many of these targets has not greatly improved clinical preservation injury over the last 20 years. This suggests that a more proximal root mechanism may be important in understanding and controlling preservation injury.

Hypothermic preservation injury is also characterized by severe membrane failure with blebbing, loss of microvilli, calcium overload, and phospholipid catabolism (13; 15; 16; 26). Membrane ultrastructural components are held in place by elements of the sub-lamellar cytoskeletal system and are important for the proper function of epithelial rich organs like the kidney (3; 6). The cytoskeletal protein ezrin, part of the ERM (Ezrin-Radixin-Moesin) family, functions as a cross-linker between the actin cytoskeleton and the plasma membrane (7). ERM proteins are involved in microvilli formation and breakdown and are also necessary for cell–cell and cell–substrate adhesions (9; 18). Membrane failure, characterized by breakdown of microvilli, increased membrane permeability, and membrane bleb formation, is a common early event in various types of apoptosis (18) and occurs during cold storage preservation (16; 23; 25; 34). Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that preservation-induced failure of the cell membrane and events distal to such failure may be caused by primary disengagement of the ezrin system supporting the plasma membrane ultrastructure. Recently, evidence from our lab suggests that disruption of the sub-lamellar cell cytoskeletal system (ezrin and spectrin) occurs during cold preservation and may cause preservation injury (23; 34). Renal tubules, tubular epithelial cells, and livers subjected to cold ischemia show biochemical and morphological signs of cytoskeletal disruption, which is attenuated by maneuvers that strengthen these systems (17; 23). Cold ischemic storage of renal tubules caused an increase in the solubility of both free ezrin and free Na/K ATPase proteins extracted from the cell membranes (23). This suggests a disassociation of ezrin binding to both the actin cytoskeletal system and to the outer cell membrane (4; 8; 37; 38).

Ezrin is a multifunctional protein and has many control points where site specific phosphorylation result in specific protein functionality. Specific phosphorylation of T567 opens the molecule and exposes both the NH2 and COOH terminus to specific binding sites on actin and the cell membrane, respectively (2; 36). This activates the cross-linker function that promotes structural integrity of the cell membrane, sub-lamellar space, and microvilli, and establishes cell polarity. Our central hypothesis is that hypothermic ischemia during kidney preservation results in ezrin structural failure of the tubular epithelium that is causally involved in expression of the renal preservation injury phenotype. We have tested this hypothesis using the pig kidney proximal tubular epithelial cell lines LLC-PK1 expressing either a constitutively active ezrin mutant (T567D) or a constitutively inactive ezrin mutant (T567A) in a cell model of hypothermic preservation injury. We have further identified and explored a novel ezrin mechanism that may involve specific binding of ezrin to mitochondria with effects on calcium sensitivity of the permeability transition pore. Previous studies from our lab have shown that ezrin is involved in hypothermic preservation injury in renal epithelial cells (23; 34) and this study’s objective is to determine the molecular mechanisms of this protection.

Materials and Methods

Materials

pEX Ezrin-YFP, an expression plasmid containing mouse wild-type Ezrin cDNA and the pig kidney proximal tubular epithelial cell line LLC-PK1 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). CytoTox 96 non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay kits were ordered from Promega Corp. (Madison, WI). Live/Dead viability/cytotoxicity kits were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Cell proliferation reagent WST-1 was ordered from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, Michigan). QuikChange®II site-directed mutagenesis kit was purchased from Stratagene ( La Jolla, CA). Rabbit anti-Ezrin antibody (H-276) and HRP conjugated secondary antibodies were ordered from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The primary anti-ezrin antibodies cross reacts with rabbit, mouse, porcine, and human ezrin.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis

To substitute the COOH-terminal threonine 567 with an alanine (T567A) or an aspartate (T567D), site-directed mutation was done with the QuikChange®II site-directed mutagenesis kit. The oligonucleotides used to introduce the T567D and T567A mutations in ezrin were (5′–3′) CAGGGACAAGTATAAGGATCTGCGGCAAATCAGGC and CAGGGACAAGTATAAGGCGCTGCGGCAAATCAGGC. Samples were denatured at 95°C for 30 s and then subjected to 12 cycles of amplification (95°C, 30 s; 55°C, 1 min; 68°C, 12 min) for the T567D and T567A mutations, respectively. The mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Stably Transfected Cell Lines

Stably transfected LLC- T567A cells and LLC-T567D were created by transfecting LLC-PK1 cells with pEX_Ezrin-T567A or pEX_Ezrin-T567D plasmid. The LLC-PK1 cells (5×105 cells/well) were seeded in 6-well plates the day before transfection. Transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) with 2 μg plasmid (containing the neomycin resistance gene) per well in Opti-MEM cell culture media. Six hours after transfection, the medium was changed. Media 199 supplemented with 5% FBS and 600 μg/ml of G418 were added to the cells and incubated for one week. The surviving cells were detached by trypsinization (Trypsin 0.25%, EDTA 0.02%, ~15 min) and analyzed on a MoFlo flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Corporation, Miami, Florida) using the 488 nm argon line of the Enterprise laser and standard optical filters. YFP-positive cells were sorted into 96-well plates, one cell per well, using the manufacturer’s Cyclone cell deposition system. Discrete colonies were picked after 1 month, re-grown, and tested for expression of YFP by flow cytometry. A maintenance concentration of 400 μg/ml of G418 was used for the growth of stably transfected clones.

Cell Culture and Cold Storage-Reperfusion

LLC-PK1 cells were grown in Media 199 (GIBCO) supplemented with 5% FBS and 50 unit/ml of penicillin-streptomycin and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. LLC- T567A and LLC- T567D cells were grown in Media 199 supplemented with 5% FBS and 400 μg/ml G418 and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. For cold preservation experiments, the cell culture plates were put into a sealed box filled with N2 gas and stored in a cold room (4°C) for 6–24 hours, removed, and rewarmed (“reperfused”) in a conventional CO2 incubator for 60 minutes. The 199 media was first purged with nitrogen gas to remove oxygen (pO2 reduced to about 20 mm Hg). For 6 hour preservation studies, the 199 media was devoid of both fetal calf serum and phenol red indicator to promote the detection of the WST-1 dye conversion at reperfusion. Since the fetal calf serum is protective for cold storage injury, the cold storage time was reduced to 6 hrs in this group. Preservation injury was measured by LDH release, mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity with WST-1 dye, or live-dead fluorescent dye staining assays.

Ezrin Knockdown and Preservation Viability

Cells at 80% confluence were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent with (3) Stealth RNAi (Invitrogen) specific for pig ezrin. Of those 3 sequences, only one was found to be effective. The sequences of the small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplex that was used in all subsequent experiments was (5′-3′): CGGACCAGAUAAAGAGCCAAGAGCA. The cells were also transfected with a negative universal RNAi control (Invitrogen). Opti-MEM (a reduced serum medium from Invitrogen) was used to dilute the siRNA duplexes for transfection. After 48 hr in cultures, the cells were placed at 4 °C for 24 hours followed by 1 hour of warm reperfusion at 37°C. The cell viability was detected using the Live/Dead viability/cytotoxicity kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and analyzed directly under a fluorescence microscope. Live cells stained with calcein AM showed green fluorescence color at 494/517 nm wavelength and dead cells stained with Ethidium homodimer 1 showed a red fluorescence color at 528/617 nm.

WST-1 assay

For determining Cell viability, LLC-PK1, LLC- T567A and LLC- T567A cells were cultured at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in 96-well microtiter plates. Twenty-four hours after attachment, the cells were cold stored at 4°C in incomplete Media 199 for 6 hours and reperfused/rewarmed for one hour at 37°C. Cell viability was assessed by adding WST-1 reagent (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan) to each well immediately before rewarming followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 hr. The optical density (OD) was then read at 450 nm by a micro-plate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT). WST-1 dye activity in cold stored-reperfused cells from the wild type and ezrin mutant colonies were compared to fresh cells without any preservation injury.

LDH Assay

Membrane permeability was used as another end point of cell viability or preservation injury and was determined by measuring the release of LDH into the culture medium after cold storage and rewarming. Cells were cultured at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in 96-well micro-titer plates. After 24 h from attachment, cells were preserved at 4°C for 6 hours followed by 1 hour warm re-oxygenation at 37°C to simulate reperfusion in the whole organ. LDH activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 490 nm using the CytoTox 96® Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and expressed as a percent of total release after cell lysis with sonication and detergent addition (Triton X-100).

Tubule and Mitochondria Preparation

Renal proximal convoluted tubules were prepared from rabbit kidneys as previously described (23). Briefly, kidneys were digested in collagenase for 1 hr under oxygen, purified on 50% Percoll (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 38,000g for 30 min, washed, and resuspended in Weinberg’s solution A (39). The tubules were homogenized in Sucrose HEPES buffer and centrifuged at 2500 RPM for 10 min. Mitochondria were harvested from supernatant by centrifugation at 11000g for 10 min at 4°C.

Specific Ezrin Binding to Mitochondria

Mitochondria were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked with 2% goat serum, and incubated with various concentrations (0.1–4.0 μg) of rabbit polyclonal anti-ezrin antibody for 1 hour. After washing away the unbound antibody (3x), the mitochondria were then incubated with FITC labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 1 hour. After 3 washes with TBS, the fluorescence was measured by FLX800 microplate reader (bio-Tek, winoosk, VT) with excitation/emission filters set at 485/325. In other experiments, ezrin binding specificity was further tested by competition with exogenous recombinant mouse wild type ezrin (produced in Dr. Mangino’s lab). Mitochondria were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and placed on poly-L-lysine coated slides. Then they were permeabilized (0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% citrate), blocked with 2% goat serum, and incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-ezrin antibody for 1 hour followed by incubation with Texas-red labeled goat anti- rabbit secondary antibody for 1 hour. After 3 washes in TBS, the mitochondria were directly analyzed under a fluorescence microscope at 1000x magnification using an excitation wavelengths 596 nm and a detection wavelength of 620 nm. Control experiments were visualized without the primary antibody to measure non-specific fluorescence. The assay was conducted with and without the presence of recombinant rabbit wild type ezrin (50 μg/ml).

Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore (mPTP)

Mouse mitochondria were isolated as described above for rabbit kidney tubules. The calcium sensitivity of the mPTP was measured by determining the threshold amount of calcium required to open the pore as described in detail (27). Briefly, mouse kidney mitochondria (125 μg protein/ml) were added to 2 ml of reaction buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 150 mM sucrose, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM KH2PO4, and 100 μM Calcium Green dye (Sigma). The mixture was gently stirred in a cuvette at 30° C in a Spectrofluorometer (Perkin Elmer Model LS55). Calcium chloride (0.5 μM) was then administered to the cuvette incrementally in 10 μl aliquots every minute and the calcium-induced fluorescence was monitored in real time. The calcium fluorescence increases at each calcium pulse and does this in a staircase fashion until the permeability transition pore opens and mitochondrial calcium rushes out to further drive the calcium signal upward. The time required for the mitochondria to lose the ability to maintain the new steady state of calcium is the point determined to be where the pore opens. This test is done for mitochondria isolated from fresh mouse kidneys and from kidneys cold stored in UW solution for 24 hrs. For each mitochondrial preparation, the mPTP opening time is determined before and after the addition of authentic recombinant mouse ezrin (50 μg/ml final) or a BSA control. This tests the effect of ezrin and cold storage on the calcium sensitivity of the mPTP.

Ezrin Western blot

kidney tubules cells and mitochondria were washed with cold PBS and lysed for 1 h with a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM, Na3V04, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mM sodium J3-glycerophosphate, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1% Triton, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 mg aprotinin, 1 pM microcystin, 1.0 pg/ml pepstatin, and 1.0 pg/ml leupeptin. The lysates were centrifuged (1 × 104 rpm at 4°C for 15 rnin). The supernatant containing 20 μg total protein was loaded in each lane of 10% gels (In-vitrogen), electrophoresed for 1 hr, transferred to PVDF membranes (Sigma) and analyzed for ezrin using an ezrin primary antibody (Santa Cruz, CA) and chemiluminescence detection (Santa Cruz, CA). Chemiluminescence was detected either by X-ray film or a chemiluminescence imager (Kodak 2000, New Haven, CT). Band intensity was calculated using Kodak molecular imaging software (Kodak MI, v4.0, Eastman Kodak, New Haven, CT).

Statistical Analysis

Most results are presented as mean ± SD. Means were obtained from 4–6 independent experiments performed in triplicate. Statistical Analysis was conducted using the GraphPad Prism version 4.00 program for windows (Graphpad Software, San Diego, California). The differences between the groups were determined by T-test for simple paired designs or one- way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post test for one-way multiple group comparisons. Ezrin binding data were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis. A P-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Results

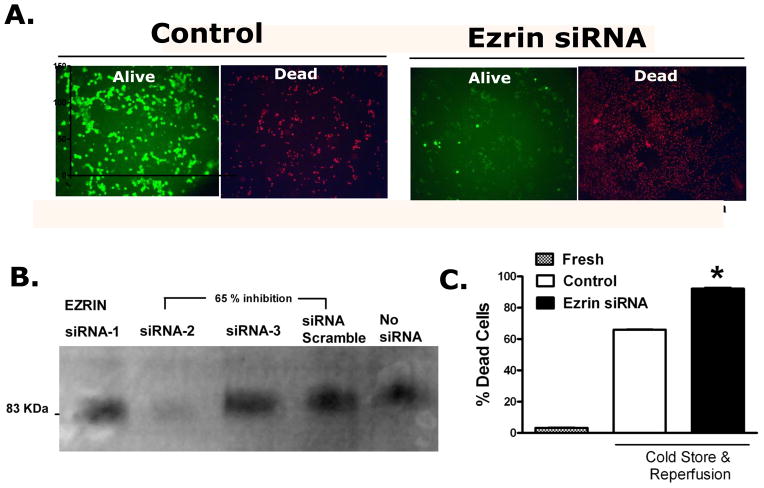

The effect of ezrin knock down on preservation injury was determined in LLC-PK1 cells. The measured outcome was cell death as determined by the fluorescence live-dead assay. Figure 1 shows the effects of 24 hrs of cold storage and 1 hour of warm re-oxygenation on cell survival and the further effects of decreasing ezrin expression through siRNA knock down. While cold storage and re-oxygenation produced about a 60% cell death per se, decreasing the expression of ezrin (by more than 50%) significantly potentiated the preservation-induced cell death.

Figure 1.

Ezrin specific siRNA knock down increases preservation injury induced cell death. Panel A: Shows the Control Alive and Dead LLC-PK1 cells that have been cold stored for 24 hrs and rewarmed for 1 hour with the siRNA vehicle. The same cells 48 hrs after ezrin specific siRNA knock down show a significant increase in cell death associated with preservation injury. Panel B: Construction of an siRNA duplex specific for ezrin (Invitrogen algorithm) was tested in LLC-PK1 cells using an ezrin specific western blot. Only one duplex worked well to produce a significant depletion in ezrin expression (siRNA-2). This duplex was used in all subsequent experiments. Panel C: The bar chart quantifies the fluorescence data (from panel A) from 6 independent experiments using image analysis (Image-J v 1.43u, National Institutes of Health). The data represent the mean ± SD, * P<0.05, relative to all other groups by ANOVA.

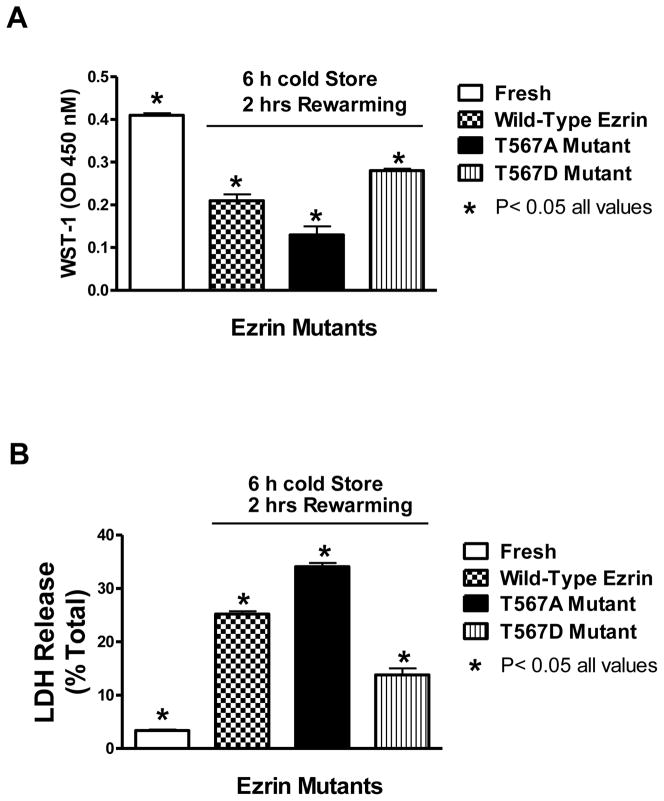

The direct effects of ezrin functionality on preservation injury are shown in figure 2. Preservation injury, indexed by either WST-1 dye conversion (upper panel) or by LDH release (lower panel), was considerable in all cells that were cold stored for 6 hours and then rewarmed for 60 minutes, relative to fresh cells without cold preservation injury. However, the cells expressing the T567A mutant were significantly more injured compared to the wild type ezrin control cells. Conversely, the cells expressing the T567D ezrin mutant experienced significantly less preservation injury, relative to the T567A mutant or the wild type cells. The T567D mutation keeps the ezrin molecule in a constitutively open configuration while the T567A mutant remains closed. The open molecule is required for ezrin to link actin to membrane structures since both NH2- and COOH- binding termini are exposed.

Figure 2.

The effects of ezrin molecular configuration on preservation injury as indexed by the WST-1 assay (A) and the LDH release assay (B). LLC-PK1 cells expressing wild type ezrin, T567A ezrin mutant (inactive), or the T567D mutant (active) were cold stored for 6 hours and then rewarmed (reperfused) for 1 additional hour to induce cold storage preservation injury. The cell culture media used for this experiment did not contain either fetal calf serum proteins or phenol red indicators, since these components interfere with the WST-1 assay. Immediately before rewarming in the incubator, the cells were given WST-1 dye to convert during the reperfusion phase. After reperfusion, the dye conversion was read on a plate reader and the LDH release was determined with a colorimetric kit. Values represent mean ± SD for 6 independent experiments that were conducted in triplicate, P< 0.05 for all values.

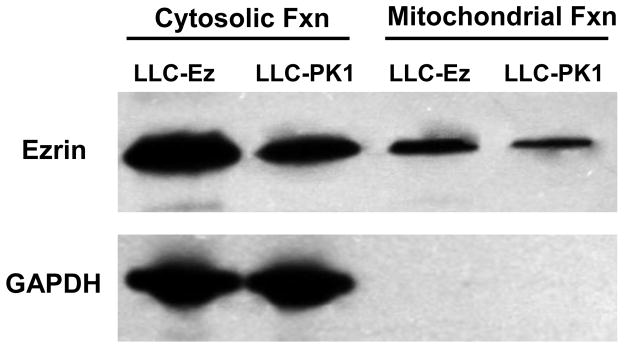

Since previous studies suggest that the salutary effects of expressing wild type ezrin in renal epithelial cells exposed to hypothermic preservation injury may be related to bioenergetics (34), a closer examination of ezrin and mitochondria was undertaken. Mitochondrial purification resulted in a mitochondrial fraction (for subsequent testing) and everything else, which was cytosolic and membrane fractions. Western blot analysis shown in figure 3 indicates that ezrin is found in purified mitochondria, albeit at lower levels than are found in the cytosolic and membrane fraction (labeled as cytosolic fraction on the figure). The ezrin signal from mitochondria (and cytosol) is significantly enhanced in LLC-Ez cells, which are LLC-PK1 cells that have been stably transfected with wild type ezrin (23). The purity of the mitochondrial fraction was verified by measuring GAPDH protein in the mitochondrial and cytosolic/membrane fractions. Since GAPDH is found exclusively in the cytosol and not mitochondria, it can be used as a marker of mitochondrial purity. The lack of GAPDH signal in the mitochondrial fraction verifies its purity. Therefore, the ezrin detected in the mitochondrial pool is likely not due to cross contamination from cytosolic or membrane sources, which are rich in ezrin.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of ezrin and GAPDH from protein extracts derived from renal tubule epithelial cells (LLC-PK1) and LLC-PK1 cells transfected with the wild type ezrin gene (LLC-Ez). LLC-Ez cells constitutively over express wild-type ezrin and produced more ezrin compared to the native LLC-PK1 cells (23). Cells were fractionated into mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial pools using a mitochondrial isolation kit for cultured cells (#89874, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL, USA). The non-mitochondrial pools included cytosolic and membrane fractions. Both the purified mitochondrial and the cytosolic/membrane fractions were analyzed for ezrin and GAPDH by western blot. Ezrin was identified in both mitochondrial and cytosolic/membrane pools. GAPDH, an enzyme exclusive to the cytosol, was used to verify the purity of the mitochondrial preparation since cross contamination with cytosolic or membrane fractions could account for any or all of the observed ezrin protein identification in the mitochondrial samples. The lack of any GAPDH signal in the mitochondrial extracts imply purity of the preparation and, more importantly, indicates that the ezrin detected in the mitochondrial fraction extracts derived from the mitochondria and not from cross contamination from ezrin rich membrane or cytosolic pools.

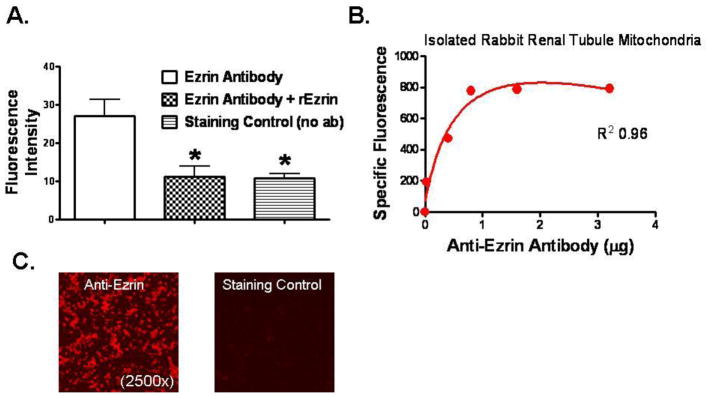

To determine if the ezrin protein extracted from purified mitochondria (Figure 3) was surface bound, immunofluorescence experiments were conducted using purified and fixed whole mitochondria isolated from mouse kidneys. Figure 4 shows that increasing amounts of anti-ezrin antibody binds to fixed amounts of purified mitochondria in a saturation specific manner (panel B). Figure 4a shows that fluorescence signals from mitochondria labeled with fluorescent anti-ezrin antibodies can be significantly neutralized when authentic unlabeled recombinant wild type ezrin (rEzrin) is added to the reaction mixture, suggesting competitive inhibition. The fluorescence signal is also reduced when the primary antibody is omitted, suggesting that the signals with anti-ezrin primary antibodies are due to specific binding of the antibodies to surface bound ezrin on the mitochondria rather than nonspecific binding.

Figure 4.

Ezrin specific immunofluorescence detected with purified mitochondria isolated from renal proximal tubules. Panel A: Immunofluorescence intensity from digital photomicrographs (1,000x) taken of isolated, purified, and paraformaldehyde fixed mitochondria stained first with anti-ezrin primary antibody (2 μg/ml), washed, and then stained with a secondary antibody labeled with Texas Red. Fluorescence microscopy used an excitation wavelength of 596 nm and a detection wavelength of 620 nm. Three experimental conditions included mitochondria stained with specific anti-ezrin antibodies alone, with anti-ezrin antibodies plus authentic recombinant ezrin (617 nM), and a staining control where no primary antibody was used. Data from Image-J software (NIH, version 1.44p) and represent mean ± SD from 6 experiments, * P< 0.05 relative to the positive control with ezrin antibody staining alone (Ezrin Antibody). Panel B: Initial experiments with isolated fixed mitochondria stained with progressively higher concentrations of primary anti-ezrin antibodies and detected with a FITC-labeled secondary antibody using a spectrofluorometric 96-well plate reader (with excitation/emission filters set at 485/325, respectively). While the mitochondrial concentrations were constant, higher antibody concentrations produced higher specific fluorescent signals until the signals saturated at a primary antibody concentration of about 2 μg/ml). Panel C: Representative fluorescent photomicrographs of purified paraformaldehyde fixed mitochondria stained with specific anti-ezrin antibodies (left) or the staining controls (right) without the primary antibodies. Secondary Texas Red labeled antibodies were used for detection, magnification was at 2,500x.

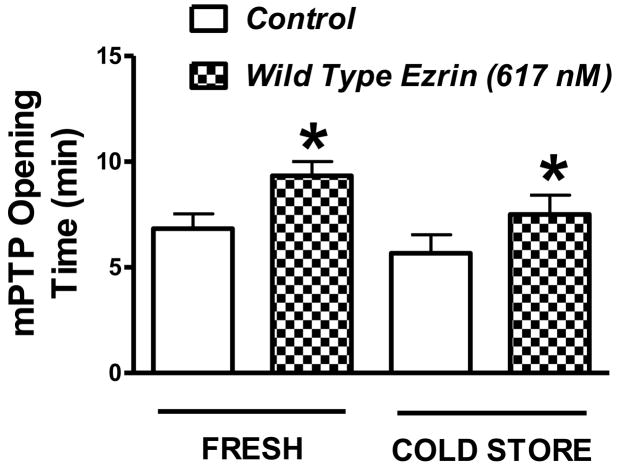

The effect of exogenous recombinant ezrin on the mPTP sensitivity to calcium is shown in figure 5. Ezrin significantly increased the time of the pore opening in mitochondria isolated from both fresh kidneys and from kidneys cold stored in UW solution for 24 hours. The increase time of opening is analogous to an increased amount of exogenous calcium required to open the pore. This in turn is a measure of the pore sensitivity to calcium. A change in calcium sensitivity of the mPTP during cold storage, however, was not observed in these studies. To control for non-specific protein effects in the ezrin treated groups, vehicle control conditions were used. The addition of BSA (50 ug/ml) to mitochondria preparations from fresh mouse kidneys did not alter the mPTP sensitivity to calcium (6.67 ± 0.57 min without BSA Vs 6.33 ± 0.57 min with BSA).

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening in response to stepwise increases in extracellular calcium in preparations of purified mouse kidney mitochondria. The extracellular calcium concentration was increased every minute and the times represent the amount of time elapsed right before the pore opens. Mitochondria were isolated from fresh kidneys and from kidneys that were flushed with UW solution and cold stored for 24 hours. The mPTP measurements were conducted with and without the addition of exogenous recombinant ezrin (617 nM) in order to test the effects of ezrin on the sensitivity of the mPTP to calcium. The mPTP studies were conducted under warm (37° C) and oxygenated (reperfusion) conditions. Values are mean ± SD from 6 independent experiments, * P< 0.05 relative to the corresponding control value (no ezrin).

Discussion

Ezrin is best known as a cytoskeletal linker protein that ties actin fibers to the plasma membrane by binding both at each end of the ezrin molecule. Earlier work indicated that ezrin time dependently disassociates from actin during cold storage ischemia in kidneys, suggesting that ezrin may be involved in preservation injury (23). A later study indicated that ezrin breakdown was causal for preservation injury and not an effect of it since up regulation of ezrin expression protected renal epithelial cells from preservation injury (34). That previous study (34) also saw significant improvement in electron microscopic evidence of plasma membrane disruption in cells over-expressing wild type ezrin since there were significantly less membrane blebs and more well formed microvilli. From these data, we hypothesized that it was ezrin’s linker role that was responsible for protecting epithelial cells from preservation injury by possibly protecting the structure of the sub-lamellar space and the plasma membrane. However, since ezrin also can affect survival signaling through Akt and PI3K (9; 10), other effects could not be excluded. Therefore, the current experiments were designed to dissect out which molecular functionality of ezrin is involved in protecting renal epithelial cells from cold storage preservation injury.

The potentiation of preservation injury in LLC-PK1 cells when ezrin expression is reduced by specific ezrin siRNA knock down confirms that ezrin plays a protective role in preservation injury in renal epithelial cells, which are the main targets of preservation injury in cold stored human kidneys. However, the same cell line expressing single point mutations of ezrin at T567 strongly indicate that the binding functionality, which is controlled by site specific phosphorylation of T567, is a main mechanism of the observed protection of wild type ezrin. Specifically, the T5657D mutant, which mimics the phosphorylated molecule, remains in the open configuration and presumably is able to maintain cytoskeletal binding. Conversely, turning off the binding configuration by constitutively blocking phosphorylation with the T567A mutation, leads to a significant potentiation of preservation injury. These data together are consistent with the hypothesis that cold storage per se, cold ischemia, or some other factors associated with cold preservation injury cause ezrin to lose its binding configuration and break away from actin/membrane binding sites, which leads to preservation injury, probably due to membrane failure as the linker functionality is lost. Membrane failure then establishes further downstream causal cascades including epithelial cell detachment from binding sites on the basement membrane, calcium overload, osmotic stress, and other events. A potential mechanism for the loss of ezrin phosphorylation at T567, if in fact it occurs, is not known but may simply be due to the loss of the overall energy charge of the cell during ischemia, which is known to reduce overall protein phosphorylation of cytoskeletal associated proteins (1). The possibility that other molecular configurations of ezrin protects these cells during cold storage injury by other mechanisms besides actin binding, cannot be excluded or determined from these data.

The cell cold storage preservation model for this study used cell culture media 199 minus additives rather than a clinical preservation solution like UW or HTK. This simplifies the end point assays (WST-1 and LDH) since the cells do not need to be washed before incubation at 37C after cold storage (reperfusion) as they would if they were cold stored in clinical preservatives solutions like UW or HTK. However, these findings and our conclusions about ezrin are still clinically relevant since our previous study (34) showed improved preservation with ezrin over-expression using a UW cold storage model. UW storage in the previous study increased the relative cold storage time compared to the current model (24 Vs 6 hrs), but an ezrin treatment effect was observed nonetheless.

A consistent finding in ezrin protected epithelial cells was a preservation of ATP levels, mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity, and retardation of the swelling effects of ischemia on mitochondria (34). While these effects could be explained by secondary effects on membrane preservation, such as reduced calcium entry, a direct effect of ezrin on mitochondrial function is possible and was explored in this study. First, mitochondria were isolated and purified to attempt identification of ezrin protein from their extracts. Indeed, ezrin was detected from mitochondrial extracts but the signal was understandably lower then that obtained from the cytosolic and membrane fractions, which are known to be highly enriched in ezrin proteins. Because of this, it became important to validate the purity of the mitochondrial preparations that were extracted for ezrin determinations since even small amounts of contamination from membrane pools could contaminate the mitochondrial ezrin results. The data suggest that the mitochondrial fraction was pure since no GAPDH was detected. Therefore, the likelihood that the ezrin measured from the mitochondria was from cross contamination with the membrane or cytosolic fractions is highly unlikely. Interestingly, the ezrin signal from the mitochondria increased in cells transfected with a wild type ezrin, suggesting that ezrin was binding or associating with mitochondria in proportion to what was being expressed in the cytosol of the cell.

Specific mitochondrial binding sites for ezrin are suggested since anti-ezrin antibodies bind to purified mitochondria in a saturation specific manner. Furthermore, ezrin-specific antibody binding detected with immunocytochemical fluorescence is reversed with the addition of authentic recombinant ezrin, probably due to competitive displacement of the antibody from the mitochondrial immobilized ezrin with the free recombinant ezrin added to the system. Equilibrium should exist between free ezrin, anti-ezrin antibodies, and mitochondrial binding sites for ezrin. Additional binding experiments are needed to describe the system better.

The exact binding sites of ezrin on the mitochondria have not yet been determined conclusively but the site likely exists on the outer mitochondrial membrane since ezrin’s molecular size (81 KDa) is probably too large to penetrate any point below the outer membrane. The next logical question is what is ezrin doing on the outer mitochondrial membrane and does it play a role in any of the events associated with hypothermic preservation injury.

Determination of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore activity in isolate mitochondria from mouse renal cortex indicated that exogenous ezrin reduces the sensitivity of the mPTP to opening by calcium stimulation. While this effect occurs in both mitochondria isolated from fresh renal tissue and from renal tissue from kidneys cold stored for 24 hours, the effect observed was not different between the two groups. This would initially suggest that while ezrin can alter mPTP function, it may not play a role in the pore opening that is associated with cold storage injury or ischemia. On the other hand, the lack of difference in the ezrin effects between fresh and stored mitochondria may be an artifact of the experiment and the isolation procedure. Specifically, injured mitochondria in cold stored tissues, which have more calcium sensitive transition pores (32), are differentially excluded from the isolation procedure since these injured mitochondria tend to swell, which alters their separation characteristics on the sucrose gradient (24). Therefore, it is likely that the isolation procedure selects out the injured mitochondria from the cold stored tissue, thus equalizing the mPTP test outcome. Furthermore, since ezrin alters mPTP function and since it likely binds on the outer mitochondrial membrane due to size considerations, it is reasonable to suggest that ezrin may be binding to a component of the mPTP on the outer mitochondrial membrane. Possible candidates to explore include VDAC (Voltage Dependent Anion Channel) and ANT (Adenine Nucleodite Translocator) since both proteins are probable constituents of the pore at its outer membrane surface (14). Immunoprecipitation studies and FRET analysis are needed to test these possibilities further.

The dependency of any particular molecular configuration of ezrin for mitochondrial binding is not currently known. However, if endogenous ezrin plays a physiological role in modifying mPTP opening during preservation ischemia, then the preferred mitochondrial binding configuration may be in the membrane unbound or “off” mode since ezrin assumes that configuration after it unbinds from the membrane and only then would it be most likely available for binding elsewhere. Specifically, the ezrin molecule assumes a circular configuration in the unbound state as it disassociates from the membrane due to dephosphorylation of the T567 control site. This exposes the autobinding sites on the NH2 and COOH termini and the molecule assumes a looped structure. Therefore, it may be that as ezrin unbinds from the cell membrane during ischemia it then becomes available to bind to the mitochondria in the cytosol. This hypothesis will be addressed by performing future mitochondrial binding assays with recombinant mutants of ezrin that assume specific molecular configurations (open or closed). If ezrin does play a role in altering mitochondrial function during ischemia, it may do so as a negative feed back modifier by attenuating the ischemia-induced permeability transition pore. This could also be an additional mechanism that explains ezrin protection in renal epithelial cells during cold storage injury.

In conclusion, ezrin protects renal epithelial cells during cold storage injury by maintaining a linker binding configuration. Ezrin also seems to be involved in specific binding to mitochondria and may desensitize the permeability transition pore to elevated calcium during cold storage ischemia and preservation injury.

Acknowledgments

The use of the VCU Microscopy Core Facility is greatly appreciated as is the helpful assistance of Dr. Scott Henderson, the Core’s Director.

Grants

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health R01-DK-087737 and by funds from the Medical College of Virginia Foundation (MCVF).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Alderliesten M, de GM, Oldenampsen J, Qin Y, Pont C, van BL, van de WB. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation during renal ischemia/reperfusion mediates focal adhesion dissolution and renal injury. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:452–462. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Algrain M, Turunen O, Vaheri A, Louvard D, Arpin M. Ezrin contains cytoskeleton and membrane binding domains accounting for its proposed role as a membrane-cytoskeletal linker. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:129–139. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apodaca G. Endocytic traffic in polarized epithelial cells: role of the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton. Traffic. 2001;2:149–159. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.020301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aufricht C, Bidmon B, Ruffingshofer D, Regele H, Herkner K, Siegel NJ, Kashgarian M, van Why SK. Ischemic conditioning prevents Na, K-ATPase dissociation from the cytoskeletal cellular fraction after repeat renal ischemia in rats. Pediatr Res. 2002;51:722–727. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belzer FO, Southard JH. Principles of solid-organ preservation by cold storage. Transplantation. 1988;45:673–676. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198804000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berryman M, Franck Z, Bretscher A. Ezrin is concentrated in the apical microvilli of a wide variety of epithelial cells whereas moesin is found primarily in endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 1993;105 ( Pt 4):1025–1043. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.4.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bretscher A, Reczek D, Berryman M. Ezrin: a protein requiring conformational activation to link microfilaments to the plasma membrane in the assembly of cell surface structures. J Cell Sci. 1997;110 ( Pt 24):3011–3018. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.24.3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Doctor RB, Mandel LJ. Cytoskeletal dissociation of ezrin during renal anoxia: role in microvillar injury. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C784–C795. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.3.C784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crepaldi T, Gautreau A, Comoglio PM, Louvard D, Arpin M. Ezrin is an effector of hepatocyte growth factor-mediated migration and morphogenesis in epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:423–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.2.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gautreau A, Poullet P, Louvard D, Arpin M. Ezrin, a plasma membrane-microfilament linker, signals cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7300–7305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilligan BJ, Woo HM, Kosieradzki M, Torrealba JR, Southard JH, Mangino MJ. Prolonged hypothermia causes primary nonfunction in preserved canine renal allografts due to humoral rejection. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1266–1273. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauet T, Eugene M. A new approach in organ preservation: potential role of new polymers. Kidney Int. 2008;74:998–1003. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hertl M, Hertl MC, Kluth D, Broelsch CE. Hydrophilic bile salts protect bile duct epithelium during cold preservation: a scanning electron microscopy study. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:207–212. doi: 10.1002/lt.500060201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Javadov S, Karmazyn M. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening as an endpoint to initiate cell death and as a putative target for cardioprotection. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007;20:1–22. doi: 10.1159/000103747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JS, Southard JH. Alteration in cellular calcium and mitochondrial functions in the rat liver during cold preservation. Transplantation. 1998;65:369–375. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199802150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JS, Southard JH. Membrane stabilizing effects of calcium and taxol during the cold storage of isolated rat hepatocytes. Transplantation. 1999;68:938–943. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199910150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohli V, Gao W, Camargo CA, Jr, Clavien PA. Calpain is a mediator of preservation-reperfusion injury in rat liver transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9354–9359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondo T, Takeuchi K, Doi Y, Yonemura S, Nagata S, Tsukita S. ERM (ezrin/radixin/moesin)-based molecular mechanism of microvillar breakdown at an early stage of apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:749–758. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.3.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CM, Carter JT, Alfrey EJ, Ascher NL, Roberts JP, Freise CE. Prolonged cold ischemia time obviates the benefits of 0 HLA mismatches in renal transplantation. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1016–1019. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.9.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Locke JE, Segev DL, Warren DS, Dominici F, Simpkins CE, Montgomery RA. Outcomes of kidneys from donors after cardiac death: implications for allocation and preservation. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1797–1807. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangino MJ, Jendrisak MD, Murphy MK, Halstead M, Anderson CB. Prostanoids and hypothermic renal preservation injury. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1990;41:173–179. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(90)90086-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mangino MJ, Mangino JE, Kotadia B, Sielczak M. Effects of the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor A-64077 on intestinal hypothermic organ preservation injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:950–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangino MJ, Tian T, Ametani M, Lindell S, Southard JH. Cytoskeletal involvement in hypothermic renal preservation injury. Transplantation. 2008;85:427–436. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31815fed17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murfitt RR, Stiles JW, Powell WJ, Jr, Sanadi DR. Experimental myocardial ischemia characteristics of isolated mitochondrial subpopulations. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1978;10:109–123. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(78)90036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neto JS, Nakao A, Kimizuka K, Romanosky AJ, Stolz DB, Uchiyama T, Nalesnik MA, Otterbein LE, Murase N. Protection of transplant-induced renal ischemia-reperfusion injury with carbon monoxide. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F979–F989. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00158.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowak G, Ungerstedt J, Wernerson A, Ungerstedt U, Ericzon BG. Hepatic cell membrane damage during cold preservation sensitizes liver grafts to rewarming injury. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:200–205. doi: 10.1007/s00534-002-0760-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paillard M, Gomez L, Augeul L, Loufouat J, Lesnefsky EJ, Ovize M. Postconditioning inhibits mPTP opening independent of oxidative phosphorylation and membrane potential. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters TG, Shaver TR, Ames JE, Santiago-Delpin EA, Jones KW, Blanton JW. Cold ischemia and outcome in 17,937 cadaveric kidney transplants. Transplantation. 1995;59:191–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfaff WW, Howard RJ, Patton PR, Adams VR, Rosen CB, Reed AI. Delayed graft function after renal transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;65:219–223. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199801270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rauen U, de GH. New insights into the cellular and molecular mechanisms of cold storage injury. J Investig Med. 2004;52:299–309. doi: 10.1136/jim-52-05-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reyes-Acevedo R. [Transplantation is still on the waiting list] Rev Invest Clin. 2011;63:120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salahudeen AK, Huang H, Joshi M, Moore NA, Jenkins JK. Involvement of the mitochondrial pathway in cold storage and rewarming-associated apoptosis of human renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:273–280. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Southard JH, Belzer FO. Organ preservation. Annu Rev Med. 1995;46:235–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian T, Lindell SL, Henderson SC, Mangino MJ. Protective effects of ezrin on cold storage preservation injury in the pig kidney proximal tubular epithelial cell line (LLC-PK1) Transplantation. 2009;87:1488–1496. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a43f18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Troppmann C, Gillingham KJ, Benedetti E, Almond PS, Gruessner RW, Najarian JS, Matas AJ. Delayed graft function, acute rejection, and outcome after cadaver renal transplantation. The multivariate analysis. Transplantation. 1995;59:962–968. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199504150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turunen O, Wahlstrom T, Vaheri A. Ezrin has a COOH-terminal actin-binding site that is conserved in the ezrin protein family. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1445–1453. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.6.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Why SK, Kim S, Geibel J, Seebach FA, Kashgarian M, Siegel NJ. Thresholds for cellular disruption and activation of the stress response in renal epithelia. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:F227–F234. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.2.F227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Why SK, Mann AS, Ardito T, Thulin G, Ferris S, Macleod MA, Kashgarian M, Siegel NJ. Hsp27 associates with actin and limits injury in energy depleted renal epithelia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:98–106. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000038687.24289.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinberg JM, Davis JA, Abarzua M, Rajan T. Cytoprotective effects of glycine and glutathione against hypoxic injury to renal tubules. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:1446–1454. doi: 10.1172/JCI113224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]