Abstract

Tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic transporters (TRAP-Ts) are bacterial transport systems that have been implicated in the import of small molecules into the cytoplasm. A newly discovered subfamily of TRAP-Ts (TPATs) has four components. Three are common to both TRAP-Ts and TPATs: the P component, a ligand-binding protein, and a transmembrane symporter apparatus comprising the M and Q components (M and Q are sometimes fused to form a single polypeptide). TPATs are distinguished from TRAP-Ts by the presence of a unique protein called the “T component”. In Treponema pallidum, this protein (TatT) is a water-soluble trimer whose protomers are each perforated by a pore. Its respective P component (TatPT) interacts with the TatT in vitro and in vivo. In this work, we further characterized this interaction. Co-crystal structures of two complexes between the two proteins confirm that up to three monomers of TatPT can bind to the TatT trimer. A putative ligand-binding cleft of TatPT aligns with the pore of TatT, strongly suggesting ligand transfer between T and PT. We used a combination of site-directed mutagenesis and analytical ultracentrifugation to derive thermodynamic parameters for the interactions. These observations confirm that the observed crystallographic interface is recapitulated in solution. These results prompt a hypothesis of the molecular mechanism(s) of hydrophobic ligand transport by the TPATs.

Keywords: TRAP transporter, syphilis, Treponema pallidum, TPR motif, protein interactions, lipoproteins, SBPs, TPAT

Introduction

Treponema pallidum, the bacterial agent of syphilis, continues to pose a significant challenge to global health. Despite decades of intensive efforts to study this sexually transmitted pathogen, T. pallidum still cannot be cultivated continuously in vitro, giving rise to many unanswered questions regarding how the spirochete mobilizes its virulence traits and how its immune evasiveness culminate in chronic human infection. Although many aspects of treponemal membrane biology remain poorly defined, not the least of which is the highly unusual nature of the spirochete's outer membrane (e.g., lack of lipopolysaccharides, paucity of integral outer-membrane proteins, anchoring of the peptidoglycan to the cytoplasmic [inner] membrane, etc.), it is widely held that the dual membrane system of T. pallidum must comprise both the physical and functional interface between the pathogen and its human host. As such, studies to better understand the membrane biology of this enigmatic bacterial pathogen likely will aid in our understanding of previously unknown features of T. pallidum's parasitic strategy. Given the many experimental obstacles to studying T. pallidum, we have been taking a structural biology approach to discern the functions of selected T. pallidum membrane lipoproteins from structural and biochemical information. Membrane lipoproteins in other bacteria serve many important functions, such as nutrient uptake, immune system evasion, and antibiotic resistance (see and references therein).

Transporter systems have evolved to facilitate the movement of small molecules in and out of the bacterial cells that have a dual (outer and cytoplasmic) membrane system. Several protein-based systems are used to facilitate transport. The outer membrane usually contains non-specific pores (i.e. the porins) and receptors for specific nutrients like metal-laden siderophores (e.g. FecA and FhuA). In the latter case, energy input from the TonB/ExbB/ExbD system is required to bring the nutrient into the periplasm25. Once small molecules have entered the periplasm, they can be imported directly to the cytoplasm by a secondary transporter, or “symporter”26, which is a membrane-spanning protein that couples the import of an environmentally rare nutrient to co-import of an abundant small molecule (usually an ion). Via this coupling strategy, the overall free energy change of co-transport is favorable. Alternatively, periplasmic proteins (called substrate-binding proteins, SBPs) can specifically bind to nutrients, effectively sequestering them in the periplasm27. SBPs then diffuse to the transmembrane components of the import apparatus. In the case of ABC transporters, the laden SBP interacts with the transporter, followed by ATP hydrolysis. The hydrolytic event and attendant protein conformational changes effect the release and transport of the ligand. In a different class of transporters, called the tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic transporters (TRAP-Ts), the SBP also delivers the ligand to the transmembrane component. However, transport is not driven by ATP hydrolysis; rather, import is coupled to the thermodynamically favorable co-transport of an ion, as in secondary transporters.

An example of protein-facilitated efflux from Gram-negative bacteria is the AcrA/AcrB/TolC complex, which features a periplasm-spanning assembly of multiple copies of these three proteins32. The complex exports a wide variety of noxious agents from the cytoplasm into the extracellular environment. A proton gradient between the periplasm and cytoplasm energizes this export system.

Implicit in nearly all periplasmic transporter mechanisms is the central role of protein-protein interactions. For example, the SBP of ABC transporters must interface with the transmembrane transporter for ligand transfer to occur. Also, the association of the “TonB box” of TonB with outer-membrane transporters (e.g. FecA, FhuA, and BtuB) is necessary for the import of important metal-containing compounds, and SBPs from these systems have also been shown to interact with TonB. Such interactions must be specific enough to bar unwanted ligand entry, yet transient enough to allow multiple transfers in a short timeframe. Other protein-protein interactions are likely more long-lived, such as those forming the efflux pumps or the Q/M interactions of TRAP-Ts37.

In previous work15, our laboratory discovered a new subfamily of TRAP-Ts, which we have termed the TPATs (tetratricopeptide repeat protein-associated TRAP transporters). Canonical TRAP-Ts comprise three components: an SBP (the “P component”); a membrane-spanning transporter (the “M component”); and a small, four-helix transmembrane protein (the “Q component”) of indeterminate function30. In some cases, the M and Q components are fused into one polypeptide. The TPATs differ from the TRAP-Ts by possessing a fourth component, the “T-component.” Also, the amino-acid sequences of the P components of TPATs are distinguishable from those of TRAP-Ts; we therefore designated them “PT components”.

Structural characterization of the T component of tatTPQ/M operon of T. pallidum (TatT;15) demonstrated that this protein adopts a 13-α-helical fold that contains cryptic tetratricopeptide repeat motifs (cTPRs) and encompasses a pore. The pore is partially formed by the concave surface of the stacked cTPRs; in canonical TPRs, this surface is responsible for protein-protein interactions38. Crystallographic and hydrodynamic data showed that TatT was trimeric in solution. We also showed that the treponemal PT component, TatPT, has a structure similar to those of P components of TRAP-Ts15 P proteins are bilobed, with a prominent ligand-binding cleft between the lobes. The ligand of TatPT is not known, but some unidentified electron density was located in its cleft. Three prominent cavities leading from the cleft to the interior of TatPT were observed. Finally, we found that TatT and TatPT specifically and avidly interact in vitro and in vivo. Despite these advances, the details of the TatT/TatPT interaction and how they collaborate to effect transport remained obscure.

In the research presented here, we further explored the interaction between the T and PT components of the TPAT. We determined two crystal structures of complexes between the two proteins. The symmetry of these crystals is different, but the interactions they illuminate are nearly identical: TatPT components bind to the trimeric T components such that the clefts of the former align with the pores of the latter. These structures represent the first time that a P protein has been observed in complex with a protein other than itself. We also used analytical ultracentrifugation and site-directed mutagenesis to validate the interface revealed by the crystal structures. These data have significant implications for the potential mechanism of the TPATs.

Results

Protein Constructs

As in our previous work on this system15, the proteins used in this study are recombinant, nonacylated versions of the lipidated forms. Ordinarily, bacterial lipoproteins are synthesized such that their N-terminal residue becomes a cysteine that is modified with a diacyl glycerol moiety and a third amide-linked fatty acid, all of which serve to anchor the lipoprotein to the relevant leaflets of either the OM or the IM39. They are thus “tethered” to these membranes by their respective N-termini. To make soluble versions of T. pallidum TatT and TatPT, we genetically removed Cys1 and, in the case of TatPT, five other N-terminal residues, thereby preventing acylation during synthesis and upon signal-peptidase II-mediated translocation in the heterologous expression organism, E. coli.

Crystal structures of the 1:3 complex of TatT and TatPT

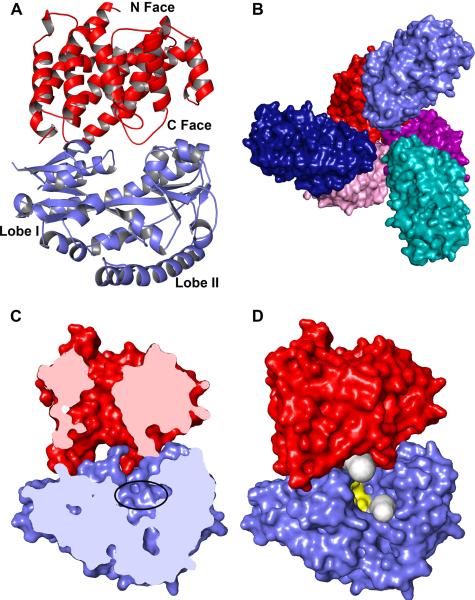

We obtained four different crystal forms of the complex of TatT and TatPT. Only two of them diffracted X-rays to the resolutions necessary for a meaningful analysis of the interaction (Table 1). In Crystal Form I, one molecule of TatT and one of TatPT are found in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 1A). This structure was refined using X-ray diffraction data to 2.7 Å resolution (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data collection, phasing and refinement statistics

| Crystal | 1:3 structure; “Form I” | 1:2 structure; “Form II” |

|---|---|---|

| Space group | R32 | P4122 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 172.9, 172.9, 150.7 | 148.9, 148.9,212.8 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Energy (eV) | 12,664.5 | 12,659.9 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 45.2 – 2.72 (2.77 – 2.72)a | 49.6 – 3.05(3.16 – 3.05) |

| Unique reflections | 23,479 (1,150) | 45,743 (4,457) |

| Multiplicity | 14.6 (9.8) | 5.1 (5.2) |

| Data completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 99.0 (98.8) |

| Rmerge (%)b | 8.3 (94.8) | 5.5 (97.0) |

| I/σ(I) | 32.6 (2.17) | 26.7 (1.68) |

| Wilson B-value (Å2) | 70.0 | 97.8 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 45.2 – 2.72 (2.82 – 2.72) | 49.6 – 3.05(3.11 – 3.05) |

| No. of reflections Rwork/Rfree | 23,458/1,205 (2,413/118) | 45,713/2,320 (2,433/135) |

| Data completeness (%) | 99.7 | 98.9 |

| Atoms (non-H prote in/solvent/ions) | 4,562/10 | 11,376/0 |

| Rwork (%) | 19.4 | 20.3 |

| Rfree (%) | 27.2 | 26.3 |

| R.m.s.d. bond length (Å) | 0.008 | 0.009 |

| R.m.s.d. bond angle (°) | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Mean B-value (Å2) (protein/solvent) | 81.4/57.8 | 118.7/(N/A) |

| Ramachandran plot (%) (favored/additional/disallowed)c | 96.6/3.4/0.0d | 96.3/3.6/0.1d |

| Maximum likelihood coordinate error | 0.88 | 1.0 |

| Missing residues | TatT: 2–28, 302 TatPT:5–8, 64–72, 161–166, 324–328 | TatT A:2–28, 302 TatT B: 2–28, 302 TatT C:2–28, 302 TatPTD:5–9, 66–70, 162–165, 322–328 TatPTE: 5–8, 326–328 |

Data for the outermost shell are given in parentheses.

Rmerge = 100 ΣhΣi|Ih, i— 〈Ih〉|/ΣhΣiIh, i, where the outer sum (h) is over the unique reflections and the inner sum (i) is over the set of independent observations of each unique reflection.

As defined by the validation suite MolProbity66.

Ramachandran restraints were used throughout for these refinements.

Figure 1. The 1:3 structure.

(A) The contents of the asymmetric unit of the 1:3 crystals are shown. TatT is shown in red and is oriented with its N face down. The lobes of TatPT (blue) are marked. (B) A surface representation of the 1:3 structure. The TatT trimer is shown in red shades (red, purple, and pink), with the C faces of the protomers facing the viewer. The TatPT monomers are shown in blue hues (light blue, dark blue, and teal). (C) The pore/cleft alignment. A cross section through the complex of one TatT (red) and TatPT (blue). The putative ligand-binding site of TatPT is circled. (D) Alternative means of egress for ligands of TatT and TatPT. The orientation of the complex is identical to that shown in part (C), but no cross-section is made. The two gray features are tunnels calculated by Caver65 showing openings that originate in the cleft of TatPT or the pore of TatT. Residues that bind the unidentified ligand in the uncomplexed structure of TatPT15 are colored yellow.

In this crystal structure of the complex, a single molecule of TatPT binds to a single protomer of the TatT trimer (Fig. 1A). The structure of TatT is only slightly perturbed compared to its uncomplexed state15; the root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) of the 270 comparable Cα atoms of the two structures is only 0.5 Å (Table 2). The ring-like structure of TatT comprises three prominent faces: the N-face, so-named because it harbors the N-terminus of the protein; the C-face, which is opposite the N face and harbors the protein's C-terminus; and the lateral face, which is on the outside of the protein between the N- and C-faces. Significantly, the TatT's pore, which runs from its N-face to its C-face, is preserved in the complexed protein. The structure of TatPT in this complex is also similar to the previous, uncomplexed structure15; the r.m.s.d. is 1.0 Å over nearly 300 comparable Cα atoms (Table 3). The proteins have two lobes (Lobe I, amino acids 9–136 and 226–263; and Lobe II, amino acids 137–225 and 264–320) with a cleft between them; unlike before, there is little to no evidence of a ligand bound in this cleft. Notably, a finger-like loop (residues 161–164) that extended from Lobe II to contact the putative ligand15 is not ordered in this structure; we call this loop the “cleft finger” (“CF”) below.

Table 2.

Pairwise comparisons of TatT structures

| Protein | Alone | 1:3 Structure Chain A | 1:2 Structure Chain A† | 1:2 Structure Chain B† | 1:2 Structure Chain C† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alone | - | 0.49 (270)* | 0.50 (268) | 0.55 (269) | 0.55 (270) |

| 1:3 Structure Chain A | - | - | 0.63 (269) | 0.46 (269) | 0.55 (271) |

| 1:2 Structure Chain A | - | - | - | 0.71 (268) | 0.72 (268) |

| 1:2 Structure Chain B | - | - | - | - | 0.66 (273) |

The first number is r.m.s.d. of compared Cα atoms given in units of Å, and the second is the number of “aligned” Cα's as defined by the protein structure comparison service Fold at the European Bioinformatics Institute (www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/ssm)67.

Numbers reflect a parallel refinement strategy in which no NCS restraints were applied (not shown).

Table 3.

Pairwise comparisons of TatPT structures

| Protein | Alone Chain A | Alone Chain B | 1:3 Structure Chain B | 1:2 Structure Chain D† | 1:2 Structure Chain E† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alone Chain A | - | 0.48 (314)* | 1.01 (297) | 1.04 (301) | 1.30 (308) |

| Alone Chain B | - | - | 1.04 (299) | 1.14 (306) | 1.28 (311) |

| 1:3 Structure Chain B | - | - | - | 0.83 (297) | 1.04 (300) |

| 1:2 Structure Chain D | - | - | - | - | 1.06 (305) |

The first number is r.m.s.d. of compared Cα atoms given in units of Å, and the second is the number of “aligned” Cα's as defined by the protein structure comparison service Fold at the European Bioinformatics Institute (www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/ssm)67.

Numbers reflect a parallel refinement strategy in which no NCS restraints were applied (not shown).

Application of a three-fold crystallographic symmetry axis to the contents of this asymmetric unit recapitulates the previously observed trimer of TatT and reveals that it is occupied by three TatPTs (Fig. 1B). Because this complex features 1 TatT trimer and 3 TatPT monomers, we term it the “1:3 structure”. There are no TatPT - TatPT contacts in this context; the nearest approach of any two TatPT atoms in the 1:3 structure is about 8 Å. Both lobes of TatPT contact TatT on its C-face. Thus, the binding interface is opposite the N-face of TatT, where the protein is ostensibly modified with lipoyl groups that anchor it in a membrane. TatPT therefore binds on the side of the protein that is likely to be oriented away from the membrane.

Provocatively, the cleft of TatPT aligns well with the pore of TatT (Fig. 1C). This alignment has a profound implication for the functioning of this transporter: it suggests that small molecules could pass from TatPT's cleft to TatT's pore, or vice versa. If true, this supposition provides TatT with a specific role in ligand transport (see Discussion). However, this interface is not “ligand-tight”; a small molecule moving from the pore to the cleft could alternatively escape to the extramolecular space (i.e. the periplasm) through a large portal at least 10 Å in diameter (Fig. 1D). The size of the portal is exaggerated by the disorder of the CF in this structure, but even if it were ordered, a large opening would exist. These observations contrast with those concerning bound SBPs in ABC transporters. In the structure of a catalytic intermediate of the maltose transporter28, the SBP is bound to the transporter such that only small channels exist between a large internal cavity and the periplasm; the cognate ligand, maltose, is too large to use these channels to escape the cavity.

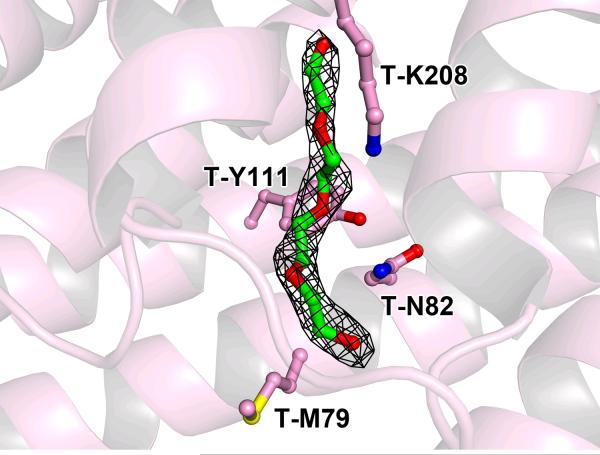

Details of the interface

Approximately 1,820 Å2 of surface area is buried upon the association of TatT and TatPT. Unexpectedly, the concave surface of the cTPRs (and by extension, the pore) of TatT is not involved in the association. Instead, most of the interaction surface of TatT is in the C-face loops between helices, and a chainlike molecule is bound in the pore (Fig. 2). We modeled this chemical as tetraethylene glycol, because of the abundance of PEG400 in the crystallization buffer (see Experimental Procedures). However, we cannot rule out other chainlike molecules, as there is no evidence of specific hydrogen-bond formation between this bound molecule and TatT.

Figure 2. Tetraethylene glycol bound in the pore of TatT in the 1:3 structure.

The buffer component is shown with green carbon atoms, surrounded by a 2mFo – DFc electron density map contoured at the 1-σ level. Some nearby residues from TatT are also shown in ball-and-stick format; their carbon atoms are shown in pink. Other atoms are colored according to a convention that shall be used henceforth in this paper: oxygen atoms are red, nitrogens are blue, and sulfurs are yellow.

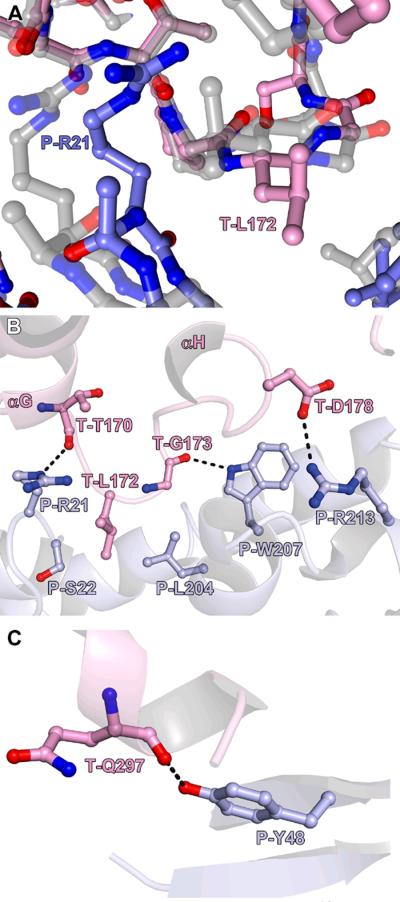

To facilitate the interaction between TatT and TatPT, surface loops of both proteins undergo significant rearrangements (Fig. 3). The largest shifts occur in loops at the interface between the two proteins; Cα atoms in these loops move by as much as 2.3 Å to accommodate the interaction (Fig. 3A). To distinguish amino-acid residues belonging to TatT from those belonging to TatPT, we adopt the convention of preceding TatT residues with a “T”, and those from TatPT with a “P”. Therefore, these loops occur near to residues T-L167 and P-R21.

Figure 3. Interactions between TatT and TatPT.

(A) Loops that accommodate the interaction. For the complex structure, the carbon atoms are colored pink for TatT and light blue for TatPT. Respectively superposed on these structures are the structures of the uncomplexed proteins (gray carbons, shown semi-transparently). T-L172 and P-R21 are labeled for reference. (B) A contact region between the two proteins. Apparent hydrogen bonds are noted with black dashes. The secondary structure (blue for TatPT, pink for TatT) of the proteins is shown semi-transparently for clarity. (C) Another contact between TatPT and TatT.

The interface between the two molecules is formed primarily by van der Waals interactions between the two proteins. Thus, shape complementarity between TatT and TatPT likely is a major determinant of their association. However, there are a few contacts that appear to be specific and/or polar. An intimate interaction between the two proteins occurs at the loop between helices αG and αH of TatT (Figs. 3A & 3B). The loop penetrates into an indentation on the surface of Lobe I of TatPT. The side chain of residue T-L172 is in contact with the side chains of residues P-L204, P-R21, and P-S22. This interaction is reciprocated by a nearby loop from TatPT that infiltrates the C-face vestibule of TatT, allowing the side chain of P-R21 to contact the main-chain oxygen atom of T-T169. Nearby, the indole nitrogen atom of P-W207 is within hydrogen-bonding distance to the main-chain oxygen atom of T-G173. At the periphery of this patch of interactions is a contact between the guanidinium group of P-R213 and the side-chain carboxylate moiety of T-D178. Another notable interaction is that between the phenolate oxygen atom of P-Y48 and the main-chain oxygen atom of T-Q297 (Fig. 3C).

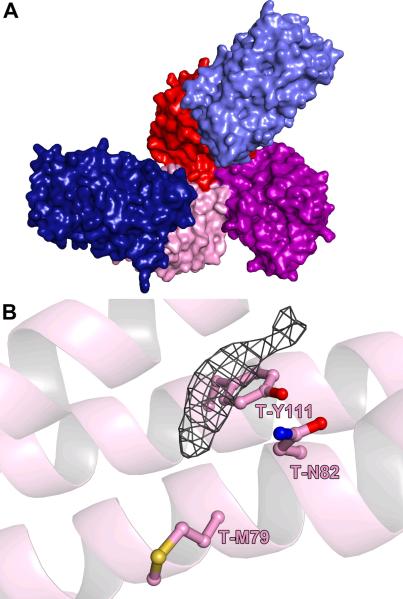

The 1:2 complex of TatT and TatPT

In Crystal Form II (resolution = 3.05 Å; Table 1), there is a trimer of TatT in the asymmetric unit, but only two molecules of TatPT are bound to it (Fig. 4A). Instead of engaging a third copy of TatPT, the “empty” TatT protomer contacts a complex from a neighboring asymmetric unit. We designated this structure as the “1:2 structure”. Using the concentrations used for crystallization, mass-action law, and the thermodynamic parameters that we calculated before15, about 48% of the TatT trimers are engaged in a 1:2 complex under the pre-crystallization conditions (if the crystallization buffer does not perturb the equilibrium). In the case of Crystal Form II, it was apparently this population of complexes that crystallized.

Figure 4. The 1:2 structure of the TatT:TatPT complex.

(A) A surface representation of the structure. The orientation and coloration are the same as those in Figure 3A. This shows the entire protein content of the asymmetric unit of the 1:2 crystals. (B) Electron density in the pore of the 1:2 structure's chain C copy of TatT. The mesh is a 2mFo – DFc electron-density map contoured at the 1-σ level. No atoms were modeled into this density. Chain A has a similar feature (not shown).

The interaction between the TatT trimer and the TatPTs in the asymmetric unit of the Form II crystals (i.e. the 1:2 structure) is very similar to that detailed in the 1:3 structure above. A few small changes in the polar contacts detailed above are noted. For example, the distance between the indole nitrogen atom of P-W207 (Chain E) and the main-chain oxygen atom of T-G173 (Chain C) is elongated compared to the other two instances (3.7 vs. 2.9 Å). However, this difference may not be statistically significant given the coordinate error (0.9 Å) of the 1:2 structure. Also, the hydrogen bond between P-R21 (Chain D) and T-T170 is not observed in the 1:2 structure. Instead, a hydrogen bond is observed between P-R21 and T-A168.

As in the 1:3 structure, we observed electron density in the pore of TatT near to residues T-N82 and T-M79 (Fig. 4B). This density was not as elongated as that observed in the 1:3 structure. Multiple factors could be responsible for the smaller density, including (1) a smaller molecule bound here, (2) a similarly sized molecule bound, but is partially disordered, and (3) the poorer resolution of the 1:2 structure does not allow a full view of the molecule. We cannot distinguish between these possibilities at present. We note that the “empty” protomer of TatT in the asymmetric unit does not exhibit this electron-density feature, implying that TatPT “caps” TatT, preventing egress of the small molecule from the pore. This appears to occur despite the large opening that exists between the two proteins (Fig. 1D).

Conformational variability in TatT and TatPT

The available crystal structures of TatT and TatPT offer us several independent views each of these two proteins. The asymmetric-unit contents of the TatT-containing crystals (1 copy in the TatT-alone structure, 1 in the 1:3 structure, 3 in the 1:2 structure) offer us five such views and the same number is available for TatPT (2 copies in the TatPT-alone structure, 1 in the 1:3 structure, and 2 in the 1:2 structure). Statistics from pairwise comparisons of the Cα's of these structures are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Except for the loop shown in Fig. 3A, the conformation of the TatT protomers does not change significantly, regardless of its complexation status; the largest pairwise r.m.s.d. in Table 2 is about 0.7 Å. TatPT, however, displays more conformational variability. Comparisons of free vs. complexed TatPTs exhibit the largest changes, with r.m.s.d.'s up to about 1.2 Å. The CF exhibits some large changes; it is extended and well ordered when TatPT is uncomplexed, but it can be either disordered or retracted (Fig. 5A) in the complex structures. Given the proposed “Venus-fly trap” mechanism of ligand capture for P components and SBPs in general, it seemed likely that interlobe motion was responsible for the higher r.m.s.d.'s. However, superpositions of the TatPT structures disprove that hypothesis; no concerted interlobe motion is noted (Fig. 5B). The molecule of TatPT designated as Chain E in the 1:2 structure has some significant localized differences to the other four TatPTs, a fact reflected in its higher pairwise r.m.s.d.'s (Table 3). It is this molecule of TatPT that exhibits the retracted conformation of the CF, and nearby structural elements are altered, apparently as a consequence of the retraction. These conformational shifts may be stabilized by a nearby molecule of TatPT from an adjoining asymmetric unit. Compared to the other structures, the penultimate helix of 1:2 Chain E, α12, also has moved away from α13. The changes that we observe in the CF raise the possibility that protein may have a variant method of ligand capture based on the disposition of the CF rather than solely on the relative positions of the two lobes. In the complexed structures, the electron density for the TatPT molecules is noticeably worse than that of TatT in both structures. This fact is reflected in the higher average B-factors for TatPT (22 Å2 greater than TatT in the 1:3 structure, and 20 Å2 greater in the 1:2 structure), and the fact that some side chains of complexed TatPT were difficult to discern (Fig. 5A). This observation underscores the greater conformational flexibility of TatPT, as it seems likely that the protein is bound in subtly different conformations in the many unit cells of the crystals, leading to poor electron density. There was not a strong correlation between surface area buried in crystal contacts and the quality of the electron density of TatT and TatPT monomers. It is noteworthy that TatPT is not intrinsically poorly ordered, as the 1.4 Å structure of the uncomplexed protein demonstrated15.

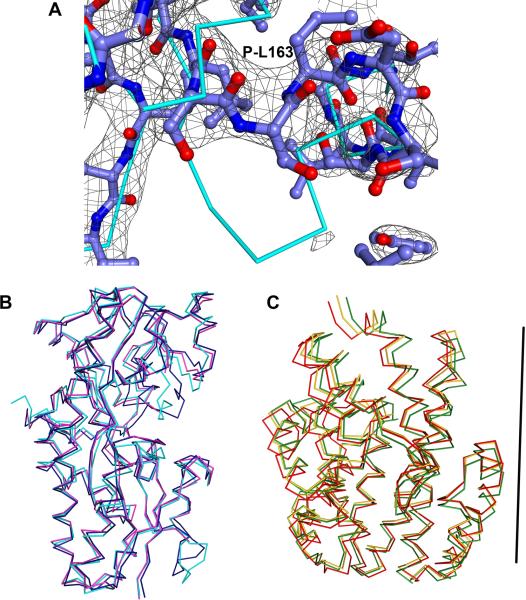

Figure 5. Comparisons of TatT and TatPT structures.

(A) CF movement. The ball-and-stick representation is the Chain E model of the 1:2 structure, and an electron-density map (2mFo – DFc; contoured at the 1-σ level) is superposed. The cyan Cα trace shows the corresponding path for the atoms of the uncomplexed TatPT structure (Chain A;15). (B) Superpositions of three copies of TatPT. Cα traces are shown for the respective structures. The A chain of uncomplexed TatPT is cyan, the E chain of the 1:2 structure is dark blue, and the B chain of the 1:3 structure is magenta. (C) Superpositions of three copies of TatT. This superposition resulted from generating trimers of TatT (where necessary) and superposing the entire trimers, not the individual protomers. However for clarity, only one protomer of the respective trimers is shown. The resulting model for uncomplexed TatT is shown in gold, Chain B of the 1:2 structure is red, and Chain A of the 1:3 structure is dark green. For reference, the position of the threefold axis of the TatT trimer is shown as a black rod.

The trimer of TatT appears to be slightly malleable. When all of the available crystal structures of TatT are compared, the individual protomers of the trimer appear to undergo a rocking motion (Fig. 5C) such that the atoms on the N and C faces move with respect to one another, but the atoms near to the center of the pore are essentially fixed. The trimer in the 1:2 structure has the C-face atoms furthest apart, while those atoms move progressively closer in the unbound TatT trimer and the 1:3 structure's trimer (this trend is opposite on the N face). This motion has the net effect of moving the bound TatPTs closer to one another in the 1:3 structure (compare Fig. 1B to Fig. 4A). At present, we cannot ascribe any functional relevance to this apparent dynamism; indeed, it may be a consequence of restrictions placed on the trimer by crystallographic symmetry. The trimer in the 1:2 structure is the only one that we have structurally characterized which is not constrained by strict threefold crystallographic symmetry, and thus may be the best representation of the solution conformation.

Solution validation of the TatT:TatPT interface

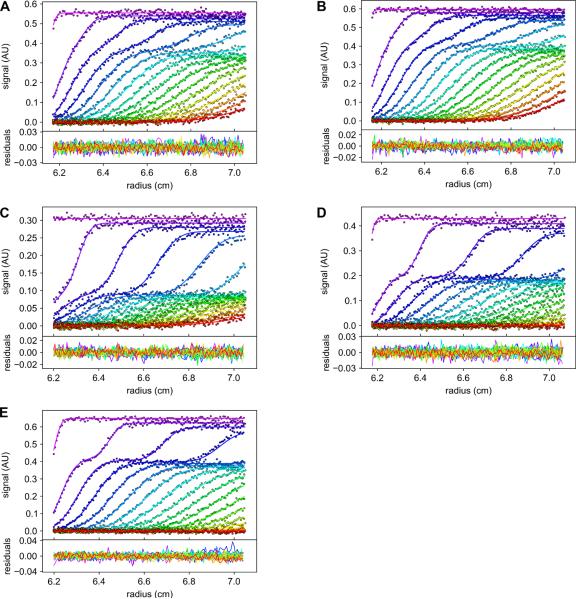

To substantiate in solution the interface that we observed in the crystal structures of the TatT:TatPT complexes, we mutated amino-acid residues on both TatPT and TatT to alanine. These point-mutant proteins were characterized using sedimentation velocity (SV) analytical ultracentrifugation. The proteins alone were characterized to ensure that the mutations did not alter their hydrodynamic behavior (data not shown). The time-dependent concentration profiles of mixtures of the proteins undergoing SV are very sensitive to the hydrodynamic and thermodynamic parameters of the system, allowing us to directly model these profiles using Lamm-equation fitting with explicit consideration of the reaction kinetics and thermodynamics. The mutant proteins were assumed to undergo the same A+B+B+B ↔ AB+B+B ↔ ABB+B ↔ ABBB association as described before15, where A ≡ TatT trimer and B ≡ TatPT. This allowed us to fit a dissociation constant (Kd(1)) for the first binding event and cooperativity factors for the second and third binding events (α2 and α3, respectively; see Table 4). The kinetic parameter (koff) was not well defined by these data, and thus was fixed at a reasonable value (1 × 10−3 s−1). Compared to the wild-type TatPT, the affinities of the P-R21A and P-Y48A proteins for TatT were substantially lowered (i.e. by a factor of ~100×) (Table 4; Fig. 6). These results strongly support the notion that the interface described above in the crystal structures (Fig. 3) is present in solution. The T-L172A, P-W207A, and P-R213A mutations resulted in more modest (factors of ~2–5) reductions in binding affinity (Table 4). Notably, the residues whose mutations cause large effects on binding are located on Lobe I of TatPT. There are several potential explanations for this phenomenon. Among them is the possibility that Lobe I's interactions are more important for the association. Also, it is conceivable that the contacts to TatT made by Lobe II are more easily replaced by solvent molecules when residues are “shaved” to alanine42.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameters of the interactions of TatT and TatPT and their mutants

| Interaction Pair | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TatT | TatPT | Kd (1) (μM) | α 2‡ | α 3‡ |

| *wild-type | wild-type | 0.06 [0.05, 0.08]† | 1.5 [1,3] | 0.34 [0.23,0.51] |

| wild-type | P-R21A | 4.1 [3.9, 4.5] | 1.0 [0.4, 1.7] | 1.0 [0.5, 1.4] |

| wild-type | P-Y48A | 2.9 [2.6, 3.2] | 0.25 [0.15,0.37] | 0.8 [0.4, 1.4] |

| wild-type | P-W207A | 0.3 [0.2, 0.5] | 3.0 [2.2, 4.7] | 0.35 [0.30, 0.47] |

| wild-type | P-R213A | 0.12 [0.11, 0.15] | 2.1 [1.1, 3.8] | 0.5 [0.3, 0.7] |

| T-L172A | wild-type | 0.21 [0.16, 0.26] | 1.1 [0.5, 2.7] | 0.6 [0.4, 0.9] |

See Deka et al.15 for the definitions of the cooperativity factors αn. Briefly, for their respective binding events, αn > 1 indicates positive cooperativity, while αn < 1 indicates negative cooperativity.

Data in this row are from Deka et al.15.

Numbers in square brackets are the inclusive 68.3% error intervals for the respective value.

Figure 6. Sedimentation velocity studies on mutant TatPTs and a mutant TatT.

The upper panels show the data (circles) and fits thereto (lines) using the Lamm Equation coupled with the kinetics and thermodynamics of the association. These symbols are color coded such that the first scan is violet, and subsequent scans step through rainbow colors, ending in red (the last scan used in the analysis). The lower panel shows the residuals between the data and the fitted lines, with identical color coding. To avoid overcrowding of the panels, only every third data point and every third scan used in the respective analysis are shown. (A) Sedimentation of P-R21A (7 μM) interacting with wild-type TatT (0.7 μM). (B) Sedimentation of P-Y48A (7 μM) interacting with wild-type TatT (0.7 μM). (C) Sedimentation of P-W207A (3.5 μM) interacting with wild-type TatT (0.7 μM). (D) Sedimentation of P-R213A (5 μM) interacting with wild-type TatT (0.7 μM). (E) Sedimentation of wild-type TatPT (8.6 μM) interacting with T-L172A (0.7 μM). Additional data and fits are shown in Figs. S1–S5.

The generality of the trimeric arrangement of T proteins

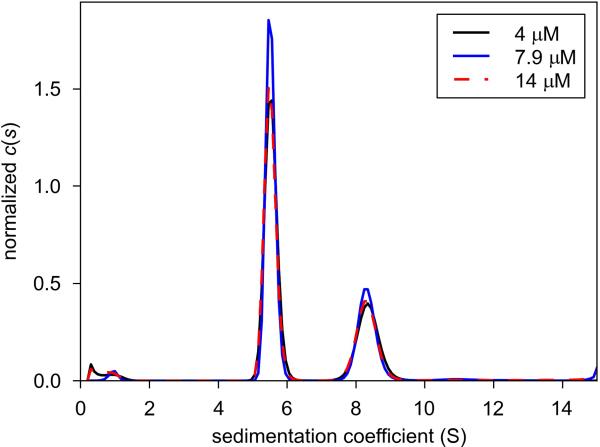

As we denoted in earlier work15, TPAT systems are found in a variety of bacterial species. Many of these species belong to the genus Treponema, and a few others also are spirochetes. Most others are oligotrophs with interesting metabolic activities, such as species known to utilize hydrocarbons as a carbon source. Previously, we showed that the TPAT T components from two treponemal species (T. pallidum and T. denticola) form trimers in solution15. The 1:2 structure offers us our first view of the trimer that is free of the requirement of perfect crystallographic symmetry. The fact that it is very similar to the crystallographically constrained trimers (Fig. 5C) indicates that this recurring trimer is very likely the one observed in solution, and that it has functional relevance. As the next step in establishing the generality of our hydrodynamic observations in the treponemal system to the entire TPAT subfamily, we cloned, overexpressed, and purified a T component (ABO_0687) from the more distantly related hydrocarbonoclastic organism Alcanivorax borkumensis. This protein shares only about 27% identity with TatT. We subjected ABO_0687 to SV and analyzed the data with the c(s) size distribution (Fig. 7). There are two main species (appearing as peaks) in this preparation, having sedimentation coefficients of 5.8 S (~70% of the signal) and 8.8 S (~30% of the signal). We found that these s-values and the signal ratios between these species were insensitive to variations in the loading concentration of the protein (Fig. 7), indicating that the two species are not in equilibrium with one another. The molar mass of the 5.8-S species calculated from these data is 97,900 g/mol. This mass is consistent with a trimer of the protein (theoretical molar mass = 102,880 g/mol). The calculated molar mass of the second species was 184,000 g/mol, suggesting that it is an irreversibly aggregated hexamer of ABO_0687. We therefore conclude that ABO_0687 forms primarily trimers in solution, and that other T components of the TPAT subfamily are likely to as well.

Figure 7. Size-distribution analysis of ABO_0687.

Shown are three c(s) distributions that have been normalized by the total signal present in each experiment. The legend at the upper right shows the three concentrations studied.

Discussion

This report provides new details concerning the interaction between TatT and TatPT. Our crystallographic results demonstrate that the two proteins bind such that the cleft of TatPT (the PT component of this TPAT transporter) aligns with the pore of TatT (the T component), strongly suggesting a ligand relay between the two proteins (Fig. 1C). Our solution data (Fig. 6) confirm that the crystallographically observed interface exists in solution. The results offer support to our earlier speculation15 that the T component of the TPAT operon is intimately involved in the transport of the target ligand.

This study offers additional insight into the nature of the ligand of this TPAT. Previously, we posited that the existence of a hydrophobic antechamber (HA) near to the N-face side of TatT's pore and the hydrophobic character of TatPT's cleft implied a hydrophobic ligand15, but there was no strong evidence regarding the shape of the ligand. In the structures presented above, there is no electron density in the HA nor in TatPT's cleft, but there is significant density in the pores of TatT molecules that are bound to TatPT (Figs. 4 & 6B). These data demonstrate that chainlike, uncharged small molecules can occupy the pore. Significantly, this density is absent in the unoccupied protomer of TatT in the 1:2 structure, implying that the presence of TatPT helps to retain such molecules in the pore under our crystallographic conditions. This retention occurs despite ample means of egress for small molecules (Fig. 1D). Hence, the environment of the TatPT-sheltered pore of TatT is favorable for the binding of such chainlike molecules relative to the bulk solvent conditions of the crystals. Such behavior could be expected for hydrophobic ligands. An example is in the crystal structure of TbuX45. This outer-membrane protein transports hydrophobic ligands across the outer membrane of Ralstonia pickettii. In the structure, a hydrophobic, chainlike detergent molecule (C8E4) binds at a solvent-exposed position on the protein. Therefore, the energetics of binding to the solvent-exposed position are more favorable than those of full solvation of the detergent. A similar phenomenon can be viewed the crystal structure of Q8XV73_RALSQ, an ortholog of MlaC, bound to a partially solvent-exposed phospholipid (PDB accession code 2qgu; no attendant publication). The crystallographic observations presented in the present paper thus still favor a hydrophobic ligand for both TatT and TatPT, and suggest that the ligand resembles an elongated chain (rather than, for example, a large conjugated ring system).

What hydrophobic compounds does T. pallidum require that could be imported by this TPAT? Analysis of the genome of T. pallidum demonstrates that it lacks the biosynthetic pathways needed to make fatty acids, nucleotides, most of the amino acids, and many other essential metabolites14; it thus must import these chemicals from its environment. Given these facts and the structural evidence at hand, palmitic acid (or other long-chain fatty acids) is a candidate for the ligand of this TPAT. Palmitate is by far the predominant long-chain fatty acid of its cellular lipids and membrane lipoproteins46. Additionally, its hydrophobicity would likely require a shuttle to escort it through the periplasm. Both the TatT pore and the TatPT Cavity A/cleft are large enough to encompass palmitic acid. Indeed, we were able to manually model a molecule of palmitic acid bound near to the position of the bound tetraethylene glycol molecule found in the TatT pore in the 1:3 structure (Fig. S6). Although channels exist in our structures for the egress of small molecules, the energy of full solvation required to accomplish dissociation and exit are probably unfavorable, thereby discouraging escape. Discovery of the identity(ies) of the TPAT ligand(s) will be a major focus of future research on the system aimed at testing hypothesized mechanisms of import (see below).

Questions of the functioning of TPATs may hinge on the overall topology of the system. The cytoplasm of T. pallidum is surrounded by a dual membrane system: an inner (cytoplasmic) membrane and an outer membrane. Tp0958 (TatQ/M), a membrane protein, is almost certainly located in the cytoplasmic membrane, where it can serve to catalyze the import of the target substrate. As periplasmic lipoproteins, TatT and TatPT must be tethered to either the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane or the inner leaflet of the outer membrane. Thus, four scenarios exist: (1) Both proteins are tethered to the inner membrane. (2) Both proteins are tethered to the outer membrane. (3) TatT is tethered to the outer membrane and TatPT to the inner. (4) TatT is tethered to the inner membrane and TatPT to the outer. We do not favor (1) or (2) because of the extreme contortions required by the tethering moieties to enable associations between trimeric TatT and more than one TatPT. The TatT:TatPT complex components, with their leader sequences extended, could span about 190 Å (Fig. 8). Recent tomographic studies of T. pallidum estimated the average width of the periplasm in non-flagellar regions to be about 200 Å. Thus, the two trans scenarios are possible, if not likely. We currently hypothesize that scenario (3) (Fig. 8) is more likely, as it retains the interaction between the PT and Q/M components. If true, TatT could deliver a ligand to TatPT, which, in turn, would hand the ligand to the integral membrane protein Tp0958. Notably, because of the topological restraints placed on TatT by its N-terminal tethers, either scenario (3) or (4) may feature the ligand passing through the protein's pore.

Figure 8. A hypothesis regarding the topology and function of TatT.

The movement of ions that is probably necessary for import is not depicted. See the text for a detailed description. The inner membrane (IM) and outer membrane (OM) of T. pallidum are shown, but, for clarity, peptidoglycan layer that exists in the periplasm is not. The T component is shown in red, and PT is shown as a blue bilobed structure, Q is yellow and M is brown. The curved lines represent the N-terminal peptides of the respective proteins, which are anchored in the membranes by acyl moieties (zigzagged lines). The approximate dimensions shown in (B) assume that the N-terminal peptides adopt a fully extended conformation.

Given our data and what is known about TRAP-Ts, we can form a speculative hypothesis (drawing on Scenario 3) regarding the functioning of the TPAT system in T. pallidum. Four steps are hypothesized (Fig. 8). (A) A “resting state” of the system, in which unliganded TatT dwells close to the outer membrane (OM). By an unknown mechanism, a hydrophobic ligand (orange oval) crosses the OM and takes up residence in the HA of one or more of the TatTs in the trimer. (B) Ligand-laden TatT diffuses away from the membrane and interacts with up to 3 copies of TatPT, inducing cargo delivery through its pore. The flexible nature of the N-terminal tails (Fig. 8) is supported by the lack of electron density for these segments in the crystal structures. Typically, our crystal structures do not resolve residues 1–28 of TatT and 1–8 of TatPT, and we have thus scaled the flexible N-termini in Fig. 8B accordingly. This complex, in which the TatPTs are empty and the Ts are loaded, resembles the 1:3 structure (Fig. 1B). The constriction in the pore of 4.8 Å apparently restricts the passage of bulky molecules15. However, the chainlike density we observe in complexed TatT (Fig. 2) is at the constriction point, illustrating that this calculated constriction is large enough to allow such molecules to pass. (C) TatPT binds to the ligand, dissociating from the TatT trimer. Conformational changes may accompany dissociation, but we have no evidence yet of that from the structures of TatPT. It does seem likely that remodeling of the CF does occur upon ligand binding, however. The existence of the 1:2 complex hypothesized in this part is supported by the 1:2 structure, our hydrodynamic studies, as well as the lack of interactions between TatPTs in the complex structures (Fig. 4). (D) TatPT in turn delivers the ligand to the transport apparatus, after which the cargo is transported into the cytoplasm. In a conventional TRAP-T, roughly the same mechanism would be employed, but there would be no TatT component; the P component would simply bind a soluble, acidic ligand in the periplasm and deliver it to the M component. Step D points out an important difference between PTs and canonical Ps: the former may bind to two partners (P and M), while the latter probably only interact with one (the M component). Further characterization of the TPAT system is required to discover whether TatPT uses similar or distinct surfaces for interacting with its partners.

In our hypothesis (Fig. 8), TatT and TatPT serve as chaperones, escorting hydrophobic ligands across the aqueous environment of the periplasm. These roles are precedented by the apparent function of the periplasmic protein MlaC of E. coli49. MlaC is thought to bind phospholipids derived from the outer membrane and shuttle them to an ABC transporter in the inner membrane. It is not difficult to imagine TatT and TatPT functioning similarly in T. pallidum. Further, in the Lol system for lipoprotein transport, LolA is thought to shuttle hydrophobic lipoproteins between the inner and outer membranes50, similar (but in the opposite direction) to what we propose for TatT and TatPT. More experimentation is required to ascertain whether the TPATs will join transporter systems like Lol and Mla as a means for hydrophobic cargo to traverse the periplasm.

A key feature of our model is the strong (Table 4) but transient interaction of TatT and TatPT. The interaction raises the question of why the TatT component is necessary, especially in bacterial species wherein the TatPT apparently is not a lipoprotein. Why couldn't TatPT simply bind the ligand proximal to the OM and deliver it to TatM? We speculate that TatT must have a specialized role that makes it particularly suited to retrieve the ligand near the OM. This newly discovered protein-protein interaction may therefore be a necessary step in ligand delivery to TatM, and the structural and thermodynamic information provided in this current report establishes a foundation to begin to explore the essentiality of this interaction in vivo. Because of the obstacle of not being able to cultivate T. pallidum in vitro, another TPAT-containing organism may be strategically exploited for testing salient aspects of our working model (Fig. 8).

Finally, the occurrence of TPAT systems in hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria15 may have important biological implications beyond relevance to T. pallidum biology and pathogenesis in humans. Alcanivoraxborkumensis and related hydrocarbonoclastic marine bacteria can utilize various aliphatic hydrocarbons as the sole source of carbon and energy. They cannot use amino acids and carbohydrates for this purpose. It is, therefore, essential that such organisms have efficient periplasmic means for the uptake and transport of required hydrophobic molecules. However, the full details of how these bacteria import metabolizable hydrocarbons are unknown. The FadL system recently has been found to support a mechanism for the transport of hydrophobic compounds from the extracellular environment to the periplasm via a channel. Further, transcriptional profiling of A. borkumensis during growth in n-alkanes induced a gene that encodes an outer membrane lipoprotein, Blc, which contains a lipocalin domain involved in the transport of small hydrophobic molecules55. However, a periplasmic trafficking mechanism for the imported hydrophobic compounds to the inner membrane receptor(s) has not been elucidated. Therefore, it is possible that undescribed periplasmic proteins exist to chaperone hydrophobic compounds across this aqueous environment. TPAT-containing species could use a relay mechanism similar to that depicted in Fig. 8 to escort insoluble but essential compounds across the periplasm to inner-membrane transporters. The observation that the ABO_0687 protein of A. borkumensis is trimeric (Fig. 7) is a first step in establishing the generality of the TPAT import mechanism.

Summary of the TPAT system

The T and PT components of the TPAT system described here and previously15 appear to be well suited to bind and transfer a hydrophobic compound(s) across the periplasmic space. Unlike most of the organisms that harbor T components, T. pallidum apparently does not possess14 orthologs of FadL, TodX, and TbuX, which are transporters specific for hydrophobic compounds56, or other outer membrane, ligand-specific channels. However, host-derived hydrophobic molecules, like fatty acids and their derivatives, are essential for the spirochete's survival, because the bacterium lacks many metabolic pathways including a de novo fatty acid synthesis pathway14. It therefore is likely that the T. pallidum first acquires hydrophobic compounds by allowing them to traverse the outer membrane via simple diffusion. The absence of lipopolysaccharides57 surrounding T. pallidum probably enhances the interaction of non-polar compounds with the treponemal outer membrane prior to their entry into the periplasm. However, the aqueous environment of the periplasm would likely cause hydrophobic compounds to form insoluble aggregates. Therefore, a system must be extant within the periplasm for the passage of hydrophobic cargo. To facilitate the movement of such compounds, a TRAP-T may have evolved to select for an additional periplasmic component, the pore-forming T protein. Once the ligand has crossed the outer membrane, the pores or HAs of T protein trimers could act as periplasmic ligand reservoirs that could relay the ligand directly to the PT protein without periplasmic exposure. This new conceptual framework may be common to all TPATs, and, as such, further studies of these bacterial transporters likely will broaden our overall understanding of the periplasmic transport of hydrophobic ligands. Our studies also have implications for developing small-molecule drugs against bacterial infections by either blocking the pore of the T component or by disrupting the T-PT interaction observed here. Also, because of the preponderance of TPAT systems in hydrocarbon-utilizing organisms, new conceptual information gleaned from our biophysical studies may have environmental implications in engineering microbes for the bioremediation of hydrocarbons.

Experimental Procedures

Protein preparation

Recombinant TatT and TatPT (Tp0956 and Tp0957, respectively) of T. pallidum were expressed and purified from Escherichia coli as described in earlier work15. Briefly, the genes for the TatT and TatPT lipoproteins were engineered into expression plasmids such that the N-terminal signal sequence and modified cysteine were absent. This renders the proteins water-soluble. TatT was expressed with an N-terminal His-SUMO tag. After affinity purification on nickel resin, the protein was purified by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), the tag was proteolytically removed, and the protein was again subjected to SEC. By contrast, TatPT had only a short His-tag on its N-terminus. After nickel-affinity purification, SEC was performed. After two weeks at 4° C, the His-tag was adventitiously proteolyzed; this protein was subject to further purification using SEC. In both cases, protein-containing fractions from the SEC columns were pooled and concentrated. The proteins were stored at 4° C in Buffer A (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.1 M NaCl, and 2 mM n-octyl β-D-glucopyranoside (β-OG)).

To produce a nonlipidated, recombinant version of Abo_0687 lipoprotein of Alcanivorax borkumensis in E. coli, a fragment encoding amino acid residues 2–259 (cloned lacking the post-translationally modified N-terminal Cys residue) was amplified by PCR from A. borkumensis genomic DNA using primers pairs encoding the 5' and 3' termini. The PCR products were ligated into pProEx HTb vector (Invitrogen) using XhoI and HindIII restriction sites such that the resultant construct encoded a fusion protein with a His-tag at its N-terminus. The construct was then transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue competent cells (Agilent Technologies); plasmids isolated from colonies that tested positive by restriction digest were verified by DNA sequencing. For expression of recombinant Abo_0687, E. coli cells harboring the fusion construct were grown at 37°C in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml of ampicillin until the cell density reached an A600 of 0.5. The temperature of the culture was then lowered to 25°C, and overexpression of the recombinant Abo_0687 was achieved by induction for ~20 h with 600 μM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and the soluble Abo_0687 was purified as described for Tp095615.

Upon sequencing the DNA plasmid used to overexpress TatPT, we discovered that it had a mutation (A185V). The protein used for crystallization (see below) harbored this mutation. However, the mutation was corrected for the AUC studies described herein.

The mutants of Tp0957 were expressed in E. coli and purified as described15. Sitedirected mutagenesis was performed using QuikChange (Stratagene). The success of the mutagenesis was monitored using DNA sequencing and electrospray mass spectrometry of the purified proteins.

Crystallization of the TatT:TatPT complex

Initial crystallization conditions for the TatT:TatPT complex were obtained by screening a roughly 1:1 (on a molar basis) mixture of the proteins against the commercial crystallization screens Wizard I & Wizard II (Emerald BioSystems, Bedford, MA). Several conditions yielded crystals, and the precipitants of these conditions could be classified into two groups: (1) small alcohols at neutral or near-neutral pH and (2) PEG solutions at high pH. Because of the difficulty in handling crystals in the presence of volatile alcohols, the second group was pursued and yielded diffraction-quality crystals upon optimization. Because the proteins tend to precipitate when mixed and crystallize readily as uncomplexed individual proteins15, molar ratio was not explored as a crystallization variable. Crystals of the TatT:TatPT complex were obtained at 20° C by mixing 2.5 μL of TatT (13 mg/mL in buffer A) with 2.5 μL TatPT (11 mg/mL in buffer A), then adding 4 μL of the optimized precipitating solution (0.1 M CHES pH 9.5, 30% (v/v) PEG-400) and incubating over 0.5 mL of this solution. We examined two crystal forms (Forms I & II). Both types of crystals were transferred to a stabilization solution of 0.1 M CHES pH 9.5, 30% (v/v) PEG-400, 0.1 M NaCl, and 2 mM n-octyl β-D-glucoside (β-OG). They were then serially transferred to similar solutions containing more PEG-400 in 5% increments; the final [PEG-400] was 40%. The crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. All data were collected at beamline 19-ID at the Structural Biology Center of the Argonne National Laboratories. The data (Table 1) were indexed, integrated, and scaled using the HKL-2000 package58.

Phase determination and model refinement

Initial phases were obtained by using Phaser59 to determine a molecular replacement solution for Form I; the TatT structure, denuded of all heterogens, was used as a search model. One molecule of TatT was located in the asymmetric unit of these crystals. Initial difference Fourier maps indicated poor electron density for one associated TatPT. The phases were improved using the density-modification protocols available in CNS version 1.160. The resulting electron-density map was used to trace the main chain of TatPT, and some of the sequence could be assigned at this stage. The resulting model was subjected to Cartesian simulated-annealing, positional, and group B-factor refinement in PHENIX61.NCS restraints were applied as appropriate. The cycles of refinement and model rebuilding resulted in the final model (Table I). Ramachandran restraints were used throughout. The TatT structure and the TatPT structure derived from Form I were used as molecular-replacement models to determine phases for the Form II structure. Three molecules of TatT and two of TatPT were found in the asymmetric unit. Refinement was carried out in PHENIX as described above (Table I).

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

The analytical ultracentrifugation experiments for mixtures of TatT and TatPT were performed as before15. These experiments were designed to study the interaction of TatT and TatPT in a titration series, with [TatT] typically held constant at about 0.7 μM, and [TatPT] varied between 0.7 and 25 μM. For each characterization, 7 titration points were studied. As before15, 390 μL of buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, and 2 mM β-OG) and the TatT/TatPT mixture (which had been equilibrated overnight at 4° C) were placed in the reference and sample sectors, respectively, of a 1.2-cm Epon dual-sectored centerpiece that had been sandwiched between two sapphire windows. The centrifugation cells were placed in an An50-Ti rotor, which was incubated at 20° C under vacuum for about 2.5 hours before centrifugation commenced. A Beckman Optima XL-I (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA) centrifuge was used to perform the experiment using a rotor speed of 50,000 rpm, and the data were collected using the on-board spectrophotometer tuned to a wavelength of 280 nm. The seven data sets were globally analyzed by direct Lamm-equation modeling using the A + B + B + B ↔ AB + B + B ↔ ABB + B ↔ ABBB model15 available in the freeware program SEDPHAT (available at sedfitsedphat.nibib.nih.gov). The buffer's density and viscosity were calculated using SEDNTERP62. The 68.3% error intervals (Table 4) were calculated using F-statistics and the “error projection” methodology63.

The experiments to determine the oligomeric state of ABO_0687 were performed using the same apparatus, except the highest concentration of the protein was placed in a centerpiece having a shorter path-length (0.3 cm) and smaller volume (100 μL). This was necessary because of its high absorbance. Three concentrations of the protein were studied: 4 μM, 7.9 μM, and 14 μM. Samples at these concentrations were incubated overnight at 4° C before being loaded into the centrifugation cells and incubated at 20° C for about 2.5 hours. The experiment then proceeded as described above, but the data were evaluated with the c(s) distribution using time-invariant noise decomposition64 in SEDFIT (also available at sedfitsedphat.nibib.nih.gov).

Accession Numbers

The 1:2 and 1:3 structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, with accession numbers 4DI3 and 4DI4, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Highlights

T. pallidum TPAT proteins TatT and TatPT interact; structural details were unknown

Their co-crystal structures provide new insights into their interaction

The observed interface is thermodynamically confirmed using mutagenesis and AUC

Characteristics of the complex are compatible with a hydrophobic ligand

Alignment of the TatT's pore and TatPT's cleft suggests a ligand-relay mechanism

Acknowledgments

We thank Martin Goldberg for technical assistance and the scientists in the UT Southwestern Protein Chemistry Core for protein-sequence and mass analyses. This research was supported by an NIH grant (AI056305) to M.V.N. This work was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (P.S.). Results in this report were derived from work performed at Argonne National Laboratory, Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source. Argonne is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Abbreviations

- TPAT

TPR-protein associated TRAP transporter

- TRAP-T

tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic transporter

- OM

outer membrane

- IM

inner membrane

- SBP

substrate-binding protein

- cTPR

cryptic tetratricopeptide repeats

- r.m.s.d.

root-mean-square deviation

- CF

cleft finger

- SV

sedimentation velocity

- HA

hydrophobic antechamber

- SEC

size-exclusion chromatography

- β-OG

n-octyl β-D-glucopyranoside

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chao JR, Khurana RN, Fawzi AA, Reddy HS, Rao NA. Syphilis: Reemergence of an Old Adversary. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2074–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen IG, Adashi EY. In the wake of Guatamala: the case for voluntary compensation and remediation. Am. J. Public Health. 2012;102:e4–e6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MS, Hawkes S, Mabey D. Syphilis returns to China...with a vengeance. Sex. Transmitted Dis. 2006;33:724–725. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000245917.47692.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerbase AC, Rowley JT, Heymann DHL, Berkley SFB, Piot P. Global prevalence and incidence estimates of selected curable STDs. Sex. Trans. Inf. 1998;74(Supp. 1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2003;290:1510–1514. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.11.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simms I, Fenton KA, Ashton M, Turner KME, Crawley-Boevey EE, Gorton R, Thomas DR, Lynch A, Winter A, Fisher MJ, Lighton L, Maguire HC, Solomou M. The Re-Emergence of Syphilis in the United Kingdom: The New Epidemic Phases. Sex. Transmitted Dis. 2005;32:220–226. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000149848.03733.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho EL, Lukehart SA. Syphilis: using modern approaches to understand an old disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:4584–4592. doi: 10.1172/JCI57173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salazar JC, Hazlett KRO, Radolf JD. The immune response to infection with Treponema pallidum, the stealth pathogen. Microb. Infect. 2002;4:1133–1140. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01638-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salazar JC, Pope CD, Moore MW, Pope J, Kiely TG, Radolf JD. Lipoprotein-Dependent and -Independent Immune Responses to Spirochetal Infection. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2005;12:949–958. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.8.949-958.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schröder NWJ, Eckert J, Stübs G, Schumann RR. Immune responses induced by spirochetal outer membrane lipoproteins and glycolipids. Immunobiology. 2008;213:329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Šmajs D, Norris SJ, Weinstock GM. Genetic diversity in Treponema pallidum: Implications for pathogenesis, evolution and molecular diagnostics of syphilis and yaws. Infect., Genet. Evol. 2012;12:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radolf JD. Treponema pallidum and the quest for outer membrane proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;16:1067–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radolf JD, Robinson EJ, Bourell KW, Akins DR, Porcella SF, Weigel LM, Jones JD, Norgard MV. Characterization of outer membranes isolated from Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Infect. Immun. 1995;63:4244–4252. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4244-4252.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser CM, Norris SJ, Weinstock GM, White O, Sutton GG, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Hickey EK, Clayton R, Ketchum KA, Sodergren E, Hardham JM, McLeod MP, Salzberg S, Peterson J, Kalak H, Richardson D, Howell JK, Chidambaram M, Utterback T, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Cotton MD, Fujii C, Garland S, Hatch B, Horst K, Roberts K, Sandusky M, Weidman J, Smith HO, Venter JC. Complete genome sequence of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Science. 1998;281:375–388. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deka RK, Brautigam CA, Goldberg M, Schuck P, Tomchick D, Norgard MV. Structural, bioinformatic, and in vivo analyses of two Treponema pallidum membrane lipoproteins reveal a unique tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporter. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;416:678–696. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deka RK, Brautigam CA, Tomson FL, Lumpkins SB, Tomchick DR, Machius M, Norgard MV. Crystal Structure of the Tp34 (TP0971) lipoprotein of Treponema pallidum: implications of its metal-bound state and affinity for human lactoferrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:5944–5958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deka RK, Brautigam CA, Yang XF, Blevins JS, Machius M, Tomchick DR, Norgard MV. The PnrA (Tp0319; TmpC) lipoprotein represents a new family of bacterial purine nucleoside receptor encoded within an ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-like operon in Treponema pallidum. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:8072–8081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deka RK, Machius M, Norgard MV, Tomchick DR. Crystal structure of the 47-kDa lipoprotein of Treponema pallidum reveals a novel penicillin-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41857–41864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207402200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Machius M, Brautigam CA, Tomchick DR, Ward P, Otwinowski Z, Blevins JS, Deka RK, Norgard MV. Structural and biochemical basis for polyamine binding to the Tp0655 lipoprotein of Treponema pallidum: putative role for Tp0655 (TpPotD) as a polyamine receptor. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;373:681–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovacs-Simon A, Titball RW, Michell SL. Lipoproteins of Bacterial Pathogens. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:548–561. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00682-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Setubal JC, Reis M, Matsunaga J, Haake DA. Lipoprotein computational prediction in spirochaetal genomes. Microbiology. 2006;152:113–121. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28317-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Driessen AJM, Rosen BP, Konings WN. Diversity of transport mechanisms: common structural principles. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:397–401. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikaido H, Saier MH., Jr. Transport proteins in bacteria: common themes in their design. Science. 1992;258:936–942. doi: 10.1126/science.1279804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rees DC, Johnson E, Lewinson O. ABC transporters: the power to change. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:218–227. doi: 10.1038/nrm2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun V. Energy-coupled transport and signal transduction through the Gram-negative membrane via TonB-ExbB-ExbD-dependent receptor proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1995;16:295–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abramson J, Wright EM. Structure and function of Na+-symporters with inverted repeats. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009;19:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davidson AL, Maloney PC. ABC transporters: how small machines do a big job. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oldham ML, Chen J. Crystal structure of the maltose transporter in a pretranslocation intermediate state. Science. 2011;332:1202–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1200767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oldham ML, Khare D, Quiocho FA, Davidson AL, Chen J. Crystal structure of a catalytic intermediate of the maltose transporter. Nature. 2007;450:515–520. doi: 10.1038/nature06264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly DJ, Thomas GH. The tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporters of bacteria and archaea. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2001;25:405–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulligan C, Geertsma ER, Severi E, Kelly DJ, Poolman B, Thomas GH. The substrate-binding protein imposes directionality on an electrochemical sodium gradient-driven TRAP transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:1778–1783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809979106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blair JMA, Piddock LJV. Structure, function and inhibition of RND efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria: an update. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009;12:512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krewulak KD, Vogel HJ. Structural biology of bacterial iron uptake. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778:1781–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsen RA, Thomas MG, Postle K. Protonmotive force, ExbB and ligand-bound FepA drive conformational changes in TonB. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;31:1809–1824. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carter DM, Miousse IR, Gagnon J-N, Martinez É, Clements A, Lee J, Hancock MA, Gagnon H, Pawelek PD, Coulton JW. Interactions between TonB from Escherichia coli and the Periplasmic Protein FhuD. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:35413–35424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.James KJ, Hancock MA, Gagnon J-N, Coulton JW. TonB Interacts with BtuF, the Escherichia coli Periplasmic Binding Protein for Cyanocobalamin. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9212–9220. doi: 10.1021/bi900722p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulligan C, Leech AP, Kelly DJ, Thomas GH. The membrane proteins, SiaQ and SiaM, from an essential stoichiometric complex in the sialic acid TRAT transporter SiaPQM (Vc1777–1779) from Vibrio cholerae. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:3598–3608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.281030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D'Andrea LD, Regan L. TPR proteins: the versatile helix. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okuda S, Tokuda H. Lipoprotein Sorting in Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;65:239–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brautigam CA. Using Lamm-equation modeling of sedimentation velocity data to determine the kinetic and thermodynamic properties of macromolecular interactions. Methods. 2011;54:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dam J, Velikovsky CA, Mariuzza RA, Urbanke C, Schuck P. Sedimentation velocity analysis of heterogeneous protein-protein interactions: Lamm equation modeling and sedimentation coefficient distributions. c(s). Biophys. J. 2005;89:619–634. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.059568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeLano WL. Unraveling hot spots in binding interfaces: progress and challenges. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:14–20. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schuck P. Size distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and Lamm equation modeling. Biophys. J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuck P, Perugini MA, Gonzales NR, Howlett GJ, Schubert D. Size-distribution analysis of proteins by analytical ultracentrifugation: strategies and application to model systems. Biophysical J. 2002;82:1096–1111. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75469-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hearn EM, Patel DR, van den Berg B. Outer-membrane transport of aromatic hydrocarbons as a first step in biodegradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8601–8606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801264105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belisle JT, Brandt ME, Radolf JD, Norgard MV. Fatty acids of Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:2151–2157. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2151-2157.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J, Howell JK, Bradley SD, Zheng Y, Zhou ZH, Norris SJ. Cellular architecture of Treponema pallidum: novel flagellum, periplasmic cone, and cell envelope as revealed by cryo electron tomography. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;403:546–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Izard J, Renken C, Hsieh C-E, Desrosiers DC, Dunham-Ems S, La Vake C, Gebhardt LL, Limberger RJ, Cox DL, Marko M, Radolf JD. Cryo-electron tomography elucidates the molecular architecture of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:7566–7580. doi: 10.1128/JB.01031-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malinverni JC, Silhavy TJ. An ABC transport system that maintains lipid asymmetry in the Gram-negative outer membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:8009–8014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903229106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Narita S.-i., Tokuda H. An ABC transporter mediating the membrane detachment of bacterial lipoproteins depending on their sorting signals. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1164–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schneiker S, dos Santos VAPM, Bartels D, Bekel T, Brecht M, Buhrmester J, Chernikova TN, Denaro R, Ferrer M, Gertler C, Goesmann A, Golyshina OV, Kaminski F, Khachane AN, Lang S, Linke B, McHardy AC, Meyer F, Nechitaylo T, Pühler A, Regenhardt D, Rupp O, Sabirova JS, Selbitschka W, Yakimov MM, Timmis KN, Vorhölter F-J, Weidner S, Kaiser O, Golyshin PN. Genome sequence of the ubiquitous hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacterium Alcanivorax borkumensis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:997–1004. doi: 10.1038/nbt1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yakimov MM, Timmis KN, Golyshin PN. Obligate oil-degrading marine bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007;18:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hearn EM, Patel DR, Lepore BW, Indic M, van den Berg B. Transmembrane passage of hydrophobic compounds through a protein channel wall. Nature. 2009;458:367–370. doi: 10.1038/nature07678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lepore BW, Indic M, Pham H, Hearn EM, Patel DR, van den Berg B. Ligand-gated diffusion across the bacterial outer membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:10121–10126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018532108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sabirova JS, Becker A, Lünsdorf H, Nicaud J-M, Timmis KN, Golyshin PN. Transcriptional profiling of the marine oil-degrading bacterium Alcanivorax borkumensis during growth on n-alkanes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011;319:160–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van den Berg B. The FadL family: unusual transporters for unusual substrates. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005;15:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Radolf JD, Norgard MV. Pathogen specificity of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum integral membrane proteins identified by phase partitioning with Triton X-114. Infect. Immun. 1988;56:1825–1828. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.7.1825-1828.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Read RJ. Pushing the boundaries of molecular replacement with maximum likelihood. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2001;57:1373–1382. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901012471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR System: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;D66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laue TM, Shah BD, Ridgeway RM, Pelletier SL. Computer-aided interpretation of analytical sedimentation data for proteins. In: Harding SE, Rowe AJ, Horton JC, editors. Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Science. The Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge, UK: 1992. pp. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bevington PR, Robinson DK. Data reduction and error analysis for the physical sciences. 2nd edit WCB/McGraw-Hill; Boston, MA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schuck P, Demeler B. Direct sedimentation analysis of interference optical data in analytical ultracentrifugation. Biophysical J. 1999;76:2288–2296. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petřek M, Otyepka M, Banáš P, Košinová P, Koča J, Damborský J. CAVER: a new tool to explore routes from protein clefts, pockets and cavities. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:316. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2256–2268. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904026460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.