Abstract

Channels formed by connexins display two distinct types of voltage-dependent gating, termed Vj- or fast-gating and loop- or slow-gating. Recent studies, using metal bridge formation and chemical cross-linking have identified a region within the channel pore that contributes to the formation of the loop-gate permeability barrier. The conformational changes are remarkably large, reducing the channel pore diameter from 15 to 20 Å to less than 4 Å. Surprisingly, the largest conformational change occurs in the most stable region of the channel pore, the 310 or parahelix formed by amino acids in the 42–51 segment. The data provide a set of positional constraints that can be used to model the structure of the loop-gate closed state. Less is known about the conformation of the Vj-gate closed state. There appear to be two different mechanisms; one in which conformational changes in channel structure are linked to a voltage sensor contained in the N-terminus of Cx26 and Cx32 and a second in which the C-terminus of Cx43 and Cx40 may act either as a gating particle to block the channel pore or alternatively to stabilize the closed state. The later mechanismutilizes the same domains as implicated in effecting pH gating of Cx43 channels. It is unclear if the two Vj-gating mechanisms are related or if they represent different gating mechanisms that operate separately in different subsets of connexin channels. A model of the Vj-closed state of Cx26 hemichannel that is based on the X-ray structure of Cx26 and electron crystallographic structures of a Cx26 mutation suggests that the permeability barrier for Vj-gating is formed exclusively by the N-terminus, but recent information suggests that this conformation may not represent a voltage-closed state. Closed state models are considered from a thermodynamic perspective based on information from the 3.5 Å Cx26 crystal structure and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The applications of computational and experimental methods to define the path of allosteric molecular transitions that link the open and closed states are discussed. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled: The communicating junctions, composition, structure and functions.

Keywords: Ion channel, Gap junction, Voltage-dependent gating, Cadmium metal-bridge, Structure–function, Molecular dynamics

1. Introduction

Different subsets of connexin proteins are expressed in almost all mammalian tissues and organ systems [1] where they form intercellular gap junction channels with diverse physiological properties. Gap junction channels are formed by the head-to-head docking of two hemichannels in adjacent cells to provide a direct communication pathway for intercellular electrical and chemical signaling. This signaling plays a vital physiological function in many organs including heart and brain, where gap junctions form electrical synapses; and in non-excitable tissues such as liver and pancreas, where they synchronize cellular activity and secretion. It has been proposed that Cx26 gap junctions in cochlear epithelium mediate IP3 transfer between supporting cells essential to sustaining the endolymphatic potential and high K+ concentration required for signal transduction and cellular homeostasis [2]. Subsets of hemichannels not docked with apposed hemichannels mediate plasma membrane currents and molecular flux in native tissues and exogenous expression systems [3–6].We term these, undocked or unapposed hemichannels. The open probability of both intercellular and undocked connexin channels is regulated by extrinsic parameters including voltage, pH, and [Ca2+] and by the intrinsic properties of the specific connexin isoforms expressed in the tissue. Recent studies indicate that undocked hemichannels have important physiological functions in health and disease. For example, misregulation of Cx26 hemichannels results in severe skin disorders that can be fatal as a consequence of secondary infection of skin lesions [7–9].

The solution of a Cx26 gap junction structure at 3.5 Å by X-ray crystallography [10] has greatly advanced our understanding of the structure–function relations of connexin channels. However, it should be kept in mind that the structure represents a single experimental determination and because it is a moderate to low resolution structure, there is a degree of uncertainty surrounding side chain positions. Therefore, while structure–function correlates can be inferred from the crystal structure, they should be viewed with a degree of caution. Recently the crystal structure has been refined with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [11]. The resulting “average equilibrated structure” appears to more closely correspond to the structure of the open Cx26 hemichannel than does the crystal structure. This review will focus on recent studies of voltage-dependent conformational changes in connexin channel structure, primarily in terms of insights gained from the crystal structure and MD simulations. Mechanisms and molecular determinants of voltage gating have been reviewed recently [12–14] and no attempt is made to provide an exhaustive review of available literature.

Connexins form large pore ion channels. The minimum pore diameter of the open channel, determined by functional studies [15, 16] is in the range of 12–15 Å. In contrast, the minimum pore diameter of the fully closed (non-conducting) channel must be less than the diameter of fully hydrated K+ (6.62 Å) and Cl− (6.64 Å) ions [17], and perhaps as small as 3.5 Å if one considers the van der Waals diameters of dehydrated K+ (5.5 Å) and Cl− (3.5 Å). The challenge from a thermodynamic perspective is to understand how such a large conformational change is accomplished. Are the conformational changes highly focal, being restricted to a specific location within the pore or are they global, i.e. changes involving multiple channel domains? Since the rate of transition is a function of the energy barrier between states [18], the question is in essence one concerning the height and width of the energy barrier separating open and closed states. The path linking open and closed states will follow the lowest energy path of the molecular transition(s) that interconnect the two. It seems reasonable to expect that the height of the energy barrier for a highly focal conformational change will be lower than that for a large global conformational change in channel structure.

2. Conformational changes mediated by extracellular calcium and pH

Studies of conformational changes in connexin channels have used a variety of methods and preparations. The first reports of conformational changes in gap junctions in response to extracellular Ca2+ in the absence of applied voltage were the cryo-EM studies of Unwin and co-workers [19–21]. They reported that low concentrations of Ca2+ (accomplished by differential dialysis) resulted in small cooperative rearrangements of rat liver gap junctions that were best explained by rigid body rotational pivoting and tilting of the six channel subunits. This led to a “camera iris” shutter model of gating reviewed by Bennett et al. [22]. More recent studies, using atomic force microscopy (AFM) [23], reviewed by Sosinsky and Nicholson [24], showed that 0.5 mM Ca2+ decreased the diameter of the extracellular entrance of Cx26 hemichannels from ~15 Å to ~6 Å. Conformational changes were also observed at the intracellular entrance of the pore, but these were more difficult to interpret as a consequence of the flexibility of the cytoplasmic surface, a feature subsequently confirmed by calculation of the temperature factors of the Cx26 crystal structure [10] and MD simulation [11]. More recently, Lal and co-workers reported Ca2+ induced conformational changes at both the intracellular and extracellular entrance to Cx40 channels [25]. The original EM and subsequent AFM studies suggest that Ca2+ gating involves substantial conformational changes of the entire channel. If so, one expects the enthalpic barrier that separates the open and closed states driven by Ca2+ concentration to be substantial, if the entropy of the open and closed states are similar. Notably, comparable structural changes determined by AFM were not induced by up to 2 mM Mg2+ in Cx26 hemichannels [23, 24]. An important question is whether the effects of Ca2+ observed in structural studies result from the direct action of Ca2+ on the channel or if the effects are indirect, mediated by changes in membrane fluidity. It has been reported that Ca2+ has amore pronounced effect on phosphatidylserine containing membranes than does Mg2+ [26] (see also [27, 28]).

The relation between conformational changes determined by structural studies and those determined electrophysiologically in response to voltage need to be examined further. One issue is the structural implication of the differential sensitivity of channels to Ca2+ and Mg2+ determined in structural studies (such as AFM) compared to the sensitivity of voltage induced conformational changes to divalent cations. In other words, are the conformational changes induced by Ca2+ and Mg2+ by themselves (chemical gating) and in combination with voltage (modulation of voltage-gating) the same?

2.1. Modulation of voltage-gating by divalent cations

Ca2+ and Mg2+ have been reported to modulate voltage-dependent loop-gate but not Vj-gate closure (see following section for definition of Vj- and loop-gating) of Cx46 hemichannels by stabilizing the closed conformation by interaction with an extracellular site outside the channel pore [29] (see also [30] for Cx32 hemichannels). This contrasts a mechanism of Ca2+ regulation of Cx37 hemichannels that is based on voltage-dependent open channel block [31] that would occur in the absence of conformational change. The Cx46 results suggest that the effect of Ca2+ requires closure of loop-gates by voltage. The structural studies, which are performed in the absence of an electrical field, suggest that Ca2+ induces conformational changes that are voltage independent. Furthermore, as described later, voltage-dependent loop-gate closure in the chimeric Cx32*43E1 hemichannel does not appear to produce substantial narrowing of the extracellular entrance to the channel pore in contrast to AFM studies of Cx26 and Cx40 closed by Ca2+. The difference suggests that the conformational changes reported in structural studies in response to Ca2+ may differ from those occurring during voltage-dependent gating.

Voltage-dependent closure of other connexin hemichannels expressed in Xenopus oocytes are known to be modulated by [Ca2+]o. including Cx26 [8, 32], but the sensitivity of Cx26 hemichannel voltage-gating modulation by Mg2+ has not been reported. Modulation of voltage-gating of Cx46 hemichannels is approximately 10 times more sensitive to Ca2+ than Mg2+ [29, 33] while that of Cx50 hemichannels is strongly dependent on Ca2+ but weakly sensitive to Mg2+ [34]. Cx32*43E1 hemichannels are ~2 times more sensitive to external Ca2+ than Mg2+ (Bargiello lab, unpublished observations). The differential sensitivity of different connexin hemichannels to Ca2+ and Mg2+ suggests that the position and or amino acid composition of the interacting site(s) differ among hemichannels. Comparison of Ca2+ and Mg2+ coordination in proteins have been investigated, for example [35], and may provide valuable information relevant to the differential sensitivity of connexins to divalent cations.

2.2. pH gating

Studies by Delmar and colleagues of gating of Cx43 channels by pH suggest a specific conformational gating mechanism: the “particle-receptor” model [36] that leads to channel closure at low pH. This model is based on a number of experimental methods including; structure–function inferences drawn from mutational analyses, interactions measured by biophysical methods including translational diffusion rates and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and structural studies of CT and CL peptides by NMR [37–40]. In this model, the cytoplasmic terminal domain (CT) of Cx43 acts as a “mobile” particle that interacts with a receptor contained within the cytoplasmic loop (CL) to effect pH gating. It is not clear if channel closure occurs by the CT directly blocking the pore or by the stabilization of the pH closed state. In contrast, pH gating of Cx46 hemichannels appears to involve the direct action of H+ ions close to the intracellular entrance of the channel pore [41]. AFM studies of the CT of Cx43 channels were interpreted to support a “ball and chain” type model for hemichannel conformational changes [42] in that the CT was shown to be flexible and not closely associated with other domains in the open state.

Conceptually analogous models to the Cx43 pH-gating model were proposed to explain voltage-gating of Cx43 and Cx40 channels [37, 43]. Based on electrophysiological studies of site directed mutations, Revilla et al. [44] proposed that some aspects of Cx32 voltage-gating arise from the movement of the CT into the channel pore. On the basis of structural studies of wild type and the Cx26M34A mutation, Oshima and co-workers [45–47] proposed a “gating plug” model in which a voltage-driven change in the position of the flexible N-terminal domain (NT) of Cx26 within the channel pore creates a permeability barrier [10, 47]. In the simplest case, the common feature shared by these gating models is that they appear to only require conformational changes restricted to a distinct flexible region of the channel. At first glance, it would appear that such transitions would not require crossing large thermodynamic barriers, at least for channel closure, if the mechanism involved the movement of a freely mobile protein domain to act as a blocking particle. The particle-receptor mechanism could have a large energy barrier if, for example, movement of the particle to its binding site was electrostatically or sterically constrained, or if the receptor domain was required to undergo a conformational (allosteric) change prior to particle binding. In the latter case, the particle could be viewed as stabilizing a conformational state. These possibilities are discussed further in Section 5.

3. Voltage-gating of connexin channels

Voltage is an important parameter regulating the opening and closing of all connexin channels. In principle, intercellular channels can be sensitive to two orientations of applied voltage, 1) the voltage difference between the cytoplasm and the extracellular space, the inside–outside voltage, termed Vi–o or Vm and 2) the voltage difference between the cytoplasms of the two cells, the trans-junctional voltage, termed Vj. Vj sensitivity depends solely on the difference in the potential of two coupled cells and is independent of the absolute membrane potential of each cell. For example, the Vj established by holding one cell at +50 and a coupled cell at −50 mV elicits the same voltage-dependent response as that created by holding one cell at 0 mV and the second cell at −100 mV in spite of differences in absolute membrane potential in the two cases. These features of connexin voltage gating have been reviewed by Bargiello and Brink [14].

Most gap junctions formed by connexins display sensitivity only to Vj, whereas those formed by the distantly related innexin gene family can display both strong Vj- and Vi–o-dependence [48]. The studies of Harris et al. [49], using vertebrate gap junctions sensitive to only Vj, established that Vj-dependence was an intrinsic hemichannel property. Each hemichannel was shown to contain a voltage sensor and gate that operates in series with the same elements located in the apposed hemichannel. A second major concept established by this study, based on the observation of contingent gating, was that the transjunctional voltage sensor would most likely reside in the channel pore. Positioning of the voltage sensor in the channel pore is required to allow sensitivity to only Vj [13, 14]. Verselis et al. [48] proposed that the Vi–o sensor would be located in the extracellular loops of invertebrate gap junctions (in the region of the intercellular gap), allowing it to move in response to Vi–o but not Vj. Note that the application of Vj in this case would activate both Vj and Vi–o (also termed Vm) gates as application of Vj must change membrane potential.

The demonstration that connexin hemichannels could open in the plasma membrane of Xenopus oocytes [50] when unapposed by another hemichannel marked a turning point in studies of the structure–function relations of connexin channels. This property expanded the range of experimental techniques that could be applied to the study of connexins, notably the application of single channel methods that provided access to both the intracellular and extracellular entrance to the channel pore. These studies lead to the identification of:

Two distinct voltage-gating mechanisms, termed “loop”- or “slow”-gating, and “Vj”- or “fast”-gating [51].

The molecular determinants and stoichiometry of Vj-gating polarity [52–54].

The identification of the location of the loop-gate permeability barrier inferred from accessibility studies [55].

The identification of amino acids in TM1/E1 region that form at least a portion of the loop-gate permeability barrier [34, 56].

The molecular determinants of charge selectivity of Cx46 and Cx32*43E1 [54, 57].

The pore lining domains of connexin channels [58, 59] with the substituted cysteine accessibility method [60]. The results of these studies indicated that hemichannel pore was formed in part by residues located in the first transmembrane domain TM1, the first extracellular loop (E1) and the N-terminus (NT). The Cx26 crystal structure is in agreement with these findings. Some experimental work suggests that TM3 lines the pore of gap junctions [61], which led to the suggestion that the structure of the channel pore changes with the formation of an intercellular channel. However, it is difficult to reconcile a role for TM3 in pore formation with the crystal structure of the Cx26 gap junction and by the formation of a portion of the loop-gate permeability barrier at the TM1/E1 boundary. A large scale reorganization of the packing order of transmembrane helices and breaking and reforming interactions with surrounding lipid resulting from hemichannel docking is unlikely to be energetically feasible.

From a biophysical and structure–function perspective, voltage gating is most effectively studied in undocked hemichannels where the operation of each gate (loop and Vj) can be directly observed. This circumvents the complication of identifying the individual contribution of four gates (2 Vj,- 2 loop-gates) operating in series that occurs in intercellular channels [62, 63]. While this is possible, it requires inferences based on mathematical models of the intercellular channels rather than direct observation of gating events.

The question then is how closely the properties of a hemichannel correspond to those of intercellular channels. Most studies indicate that there is close correspondence. Srinivas et al. [64] reported that several properties of Cx46 and Cx50 gap junction channels, including unitary conductance, sensitivity to pharmacological agents, and voltage-gating can be explained by the properties of undocked Cx46 and Cx50 hemichannels. Ebihara et al. [65] reached the same conclusion in earlier studies of the voltage gating of Cx46 and Cx56 channels as did Beahm and Hall [66] for Cx50 channels. Similar principles are evident in studies of voltage gating and current rectification of Cx26 and Cx32 [67–69], where the properties of homotypic and heterotypic intercellular channels can be explained in terms of the properties of their component hemichannels. Together, these reports support the view that the structure and function of connexin hemichannels is largely conserved when they function individually as undocked hemichannels or in series as intercellular channels. The current view is that formation of an intercellular channel can modulate the expression of voltage-dependence (an intrinsic hemichannel property) but pairing of two hemichannels does not create novel gating mechanisms.

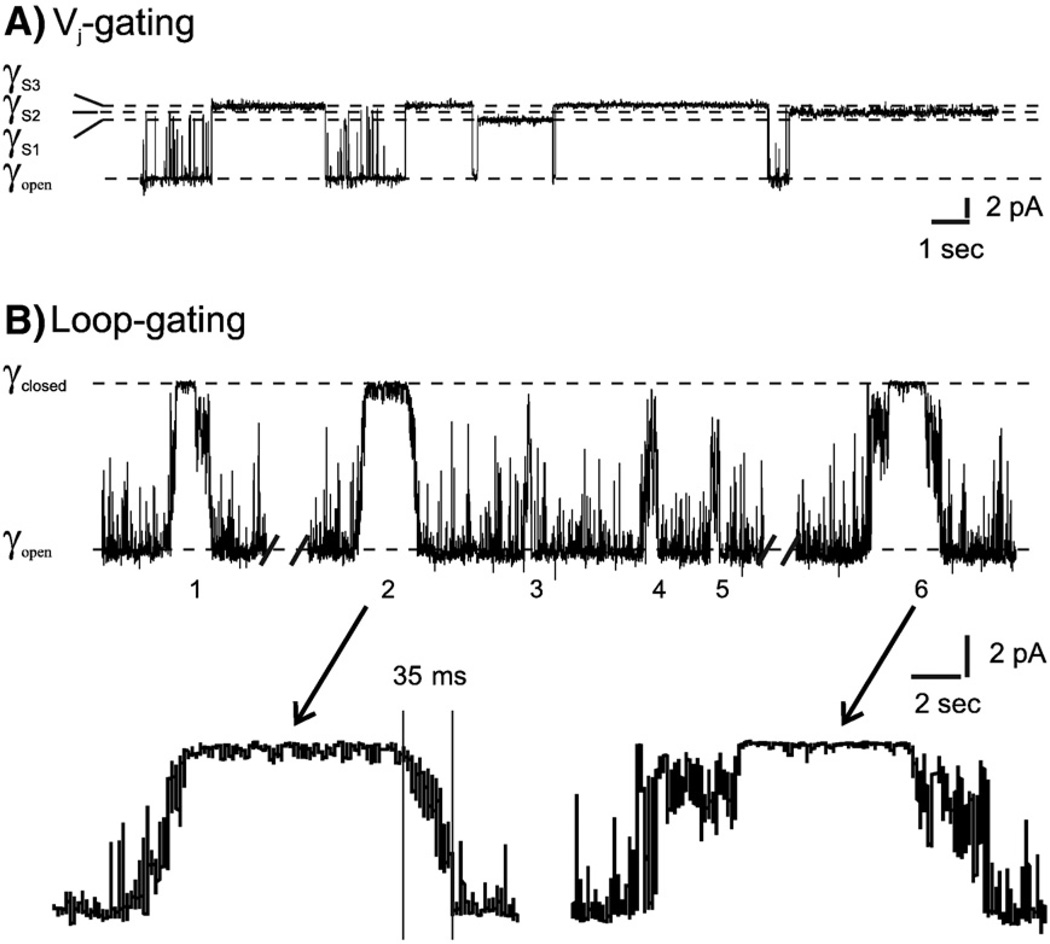

Connexin channels display at least two distinct voltage gating processes, termed loop- or slow-gating and Vj- or fast-gating that are defined by how they appear in single channel records [51, 64, 69]. These two processes were first described in insect cell lines [70] now known to be formed by innexins, a family of proteins with no sequence homology to connexins. In connexin channels, Vj or fast-gating corresponds to events in which the channel closes to distinct subconductance states with a time course that cannot be resolved in patch clamp recordings (Fig. 1A). The term Vj-gating was adopted to reflect the correspondence between the entry of the hemichannel into substates in single channel recordings and a minimal conductance, Gmin, inmacroscopic recordings of intercellular channels in response to Vj. Others use the term fast-gating rather than Vj-gating to describe the kinetics of current relaxations observed in macroscopic recordings. Bukauskas and Verselis [13] discuss the relationship between speed of gating transitions and gating kinetics. The polarity of Vj-gating differs among connexin channels formed by Cx26 and Cx32 [67], e.g. the Vj-gate of Cx32 hemichannels closes as the inside potential becomes more negative (hyperpolarization), while in Cx26 hemichannels, the Vj-gate closes as the inside potential becomes more positive (depolarization). Cx43 and Cx40 intercellular channels display a form of substate gating that has also been termed fast gating. This terminology was initially based on the kinetics of current relaxation [44] rather than the rapid time course of the gating transition. As described later, this form of gating appears to involve and interaction between the CT and CL of these connexins, and may represent a different fast-gating mechanism than described for Cx32, Cx26 and Cx46 channels.

Fig. 1.

Single channel records of an undocked Cx32*Cx43E1 hemichannel in Xenopus oocyte. (A) Outside-out record of a single channel illustrating closures by Vj-gating to three substates at a holding potential of −100 mV. (B) Cell-attached recording of a single wild-type channel illustrating six loop-gating events at a holding potential of −70 mV. Note the slow time course of the transitions indicated for events 2 and 6 in the lower panel of B and that not all transitions necessarily lead to full channel closure, as indicated by the partial closure of events 3–5.

Loop-gate closure is favored at inside negative potentials in all connexin hemichannels examined to date. In single channel recordings, loop-gating transitions between open and fully closed state pass through multiple metastable intermediate states [51]. This is illustrated in Fig. 1B for the undocked chimeric Cx32 hemichannel (Cx32*Cx43E1) first described by Dahl and co-workers [71] and characterized at the single channel level by Oh et al. [69]. It was proposed that the intermediate states reflect conformational changes by each component connexin monomer in the hemichannel [51], but this has not been confirmed. Transitions connecting the intermediate states are rapid and are not resolved in patch clamp recordings. The dwell time in any given intermediate state is voltage dependent, decreasing markedly with increasing hyperpolarization. At intermediate voltages, the transition from the open to fully closed channel has an appreciable time constant, in the millisecond range, giving the appearance of a “slow” gating event (see [13] for review and Fig. 1.B). The voltage-dependence of loop-gating favors hemichannel closure at the resting membrane potential of most cells, and thus, in combination with extracellular [Ca2+] maintains hemichannels in a closed state prior to the formation of intercellular channels. As described above, divalent cations are believed to stabilize the closed conformation.

Similar appearing slow events (loop-gating) are also observed in Cx32, Cx43, Cx45 and Cx40 intercellular channels as well as fast transitions (Vj-gating) [13, 15, 72, 73]. Thus, it appears that the loop-gating mechanism operates in both undocked hemichannels and intercellular channels in spite of constraints imposed on the position of the extracellular loops that are required for intercellular channel formation. While this observation does not exclude the possibility that the two extracellular loops participate in loop-gating, it suggests that they may not play a major role in the conformational changes required to close the channel.

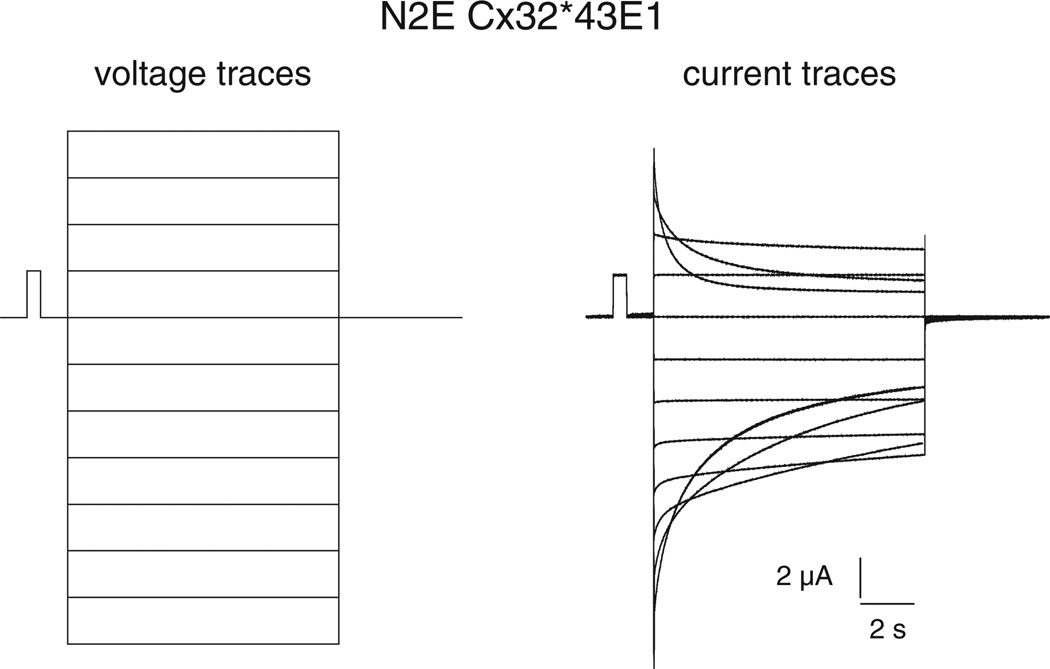

While the kinetics of Vj-gating and loop-gating have not been extensively studied in terms of kinetic models and their thermodynamic implications, the long time constants obtained from the relaxation of macroscopic currents of undocked hemichannels expressed in Xenopus oocytes strongly suggest that the energy barrier separating the open and both the Vj- and the loop-gate closed states is high. For example, the time constants of the current relaxations of a N2E–Cx32*43E1 hemichannel shown in Fig. 2 are in the order of seconds (tau for the closure of Vj-gates is ~1.25 s at 40 mV, tau for closure of loopgates is ~3.5 s at −70 mV). Recall that in this hemichannel, current relaxations observed at inside positive potentials result from closure of Vj-gates, while current relaxations observed at inside negative potentials result from closure of loop-gates. The channel is fully open at intermediate membrane potentials around 0 mV (Fig. 2). This indicates that the free energy of the open state is much lower than that of the closed states in the absence of an applied voltage. Consequently, voltage is believed to effect channel closure by the destabilization of the open state and the stabilization of the closed states. The presence of a large energy barrier is supported by kinetic analyses reported for other connexin channels (see [49, 74–76] for examples). The time constants for different connexins vary from hundreds of milliseconds to seconds. For comparison, the activation energies of the final transitions that link the open and closed states of voltage-gated Shaker K+ and squid giant axon Na+ channels can be as high as ~12–15 kcal/mol with substantial enthalpic and entropic components [77–79]. The time constants of these transitions are in the ms range, i.e. at least one or two orders of magnitude faster than the time constants reported for connexin channels.

Fig. 2.

Macroscopic recording of N2E Cx32*Cx43E1 hemichannel in Xenopus oocytes. Currents shown in the panel on the right were elicited by voltage steps from 0 mV to 40 through −70 mV in 10 mV increments shown in the voltage traces in the left panel. Current relaxations at inside positive potentials (depolarization) result from Vj-gating while those at inside negative potentials (hyperpolarization) result from loop-gating. The N2E substitution reverses the polarity of Vj-gating of the wild type Cx32*Cx43E1 hemichannel. In the wild type channel, current relaxations are only observed with hyperpolarization (not depicted).

It is important to keep in mind that two components must be considered in the kinetics of channel closure. One is the latency to the gating event, the second is the kinetics of the actual gating transition. Both may be voltage-dependent. That is, the probability that a gating event is initiated is voltage-dependent; indicating that the probability that the channel samples a conformation permissive to the transition is increased by the addition of energy to the system provided by voltage. For a multistep gating process such as loop-gating, the time spent in each of the intermediate “metastable” states is a function of the energy provided by voltage to surmount the energy barrier separating the intermediate states.

4. Conformational changes associated with loop-gate closure

A number of different methods have been applied to the study of voltage-dependent conformational changes of ion channels. These include spectroscopic methods, such as fluorescence quenching, FRET and LRET. These are reviewed in terms of potassium channel gating by Bezanilla [80, 81] and their use in defining the structure of the closed state of K+ channels is described by Pathak et al. [82].Other methods include the formation of metal bridges [83], disulfide bonds [84], and chemical crosslinking [56] as molecular rulers to establish the proximity relations between substituted residues. A comprehensive discussion of Cd2+ thiolate metal bridge formation as applied to the study of K+ channels is provided by Yellen [85]. Of these, metal bridge formation, disulfide bond formation and chemical crosslinking have proved most successful in determining the conformation of the loop-gate closed state of Cx32*43E1 and Cx50 hemichannels [34, 56].

4.1. The formation of Cd2+ thiolate metal bridges

The molecular geometry and energetics of Cd2+ thiolate interactions are well established. Cadmium is a group IIB transition metal with the electronic configuration [Kr]5s04d10. It is a highly polarizable, soft ion that forms stable complexes with soft donor atoms (S >> N > O) with a preferred coordination number of 4 reflecting its electronic configuration (i.e. the outer shell of Cd2+ can accommodate 8 electrons, 2 from the outer shell of each thiolate group). The stabilities of Cd2+–cysteine complexes are highly dependent on the number of participating thiolate groups. A tetradentate complex in which a single Cd2+ interacts with four cysteine residues is significantly more stable, i.e. has lower dissociation constant (Kd) or higher stability constant than do bidentate complexes [86, 87].

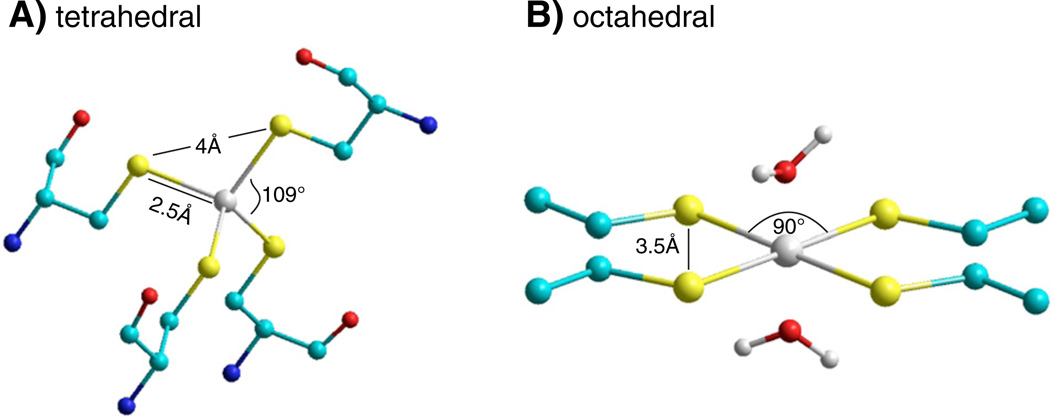

In a survey of protein crystal structures, Dokmanic et al. [88] reported that tetradendate coordination of Cd2+ by cysteine most often results from the tetrahedral organization of four cysteine-S atoms coordinated to one central Cd2+. In this geometry, the Cd—S bond length is ~2.5 Å, the S—Cd—S bond angle is ~110° and sulfur atoms are separated by 4 Å (Fig. 3A). Cd2+ coordination can also adopt an octahedral geometry with two water molecules participating when the four cysteine sulfhydryl groups are arranged in a plane [89]. In this geometry the sulfur atoms of adjacent cysteine residues are separated by 3.5 Å (Fig. 3B). Bidentate coordination of Cd2+ with 2 cysteine residues in solution may also favor a tetrahedral geometry in which the two missing cysteine residues are replaced with 2 water molecules [90]. Alternatively, a less stable bidentate site can be formed by two cysteine residues separated by ~5 Å, i.e. twice the 2.5 Å optimal distance for the S—Cd interaction, if, for example steric factors reduce the access of water to the coordination site preventing the adoption of a tetrahedral geometry.

Fig. 3.

Coordination geometries of tetradentate cysteine–Cd2+ metal bridges. (A) Tetrahedral coordination geometry showing the Cd2+—S bond distance of 2.5 Å and S—Cd2 +—S bond angle of 109°. All S atoms are separated 4 Å. (B) Planar octahedral geometry, in which the S—Cd2+—S bond angle is 90° and the distance separating all S atoms is 3.5 Å. Only the cysteine side chains are shown. The positions of 2 water molecules that participate in the coordination of Cd2+ (white atom) are shown. Sulfur atoms are yellow spheres, carbon atoms are blue spheres, oxygen atoms are red spheres, nitrogen atoms are blue spheres.

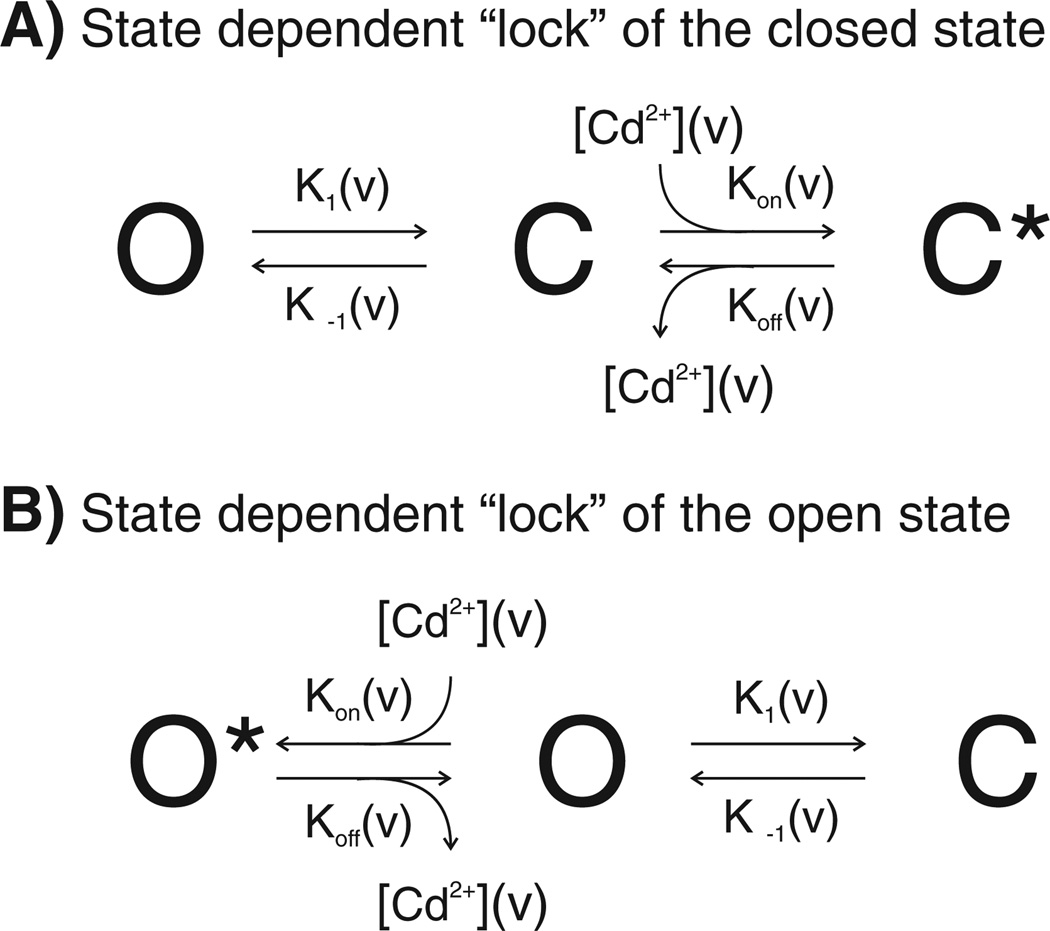

Because the binding energy of cysteines for Cd2+ is very sensitive to changes in distance, movement of cysteines during gating should introduce a strong energetic bias in favor of a gating state that optimizes the coordination geometry. If cysteines adopt a spatial configuration capable of Cd2+ coordination, then application of Cd2+ will stabilize the channel in the state that allows the lowest energy Cd2+–cysteine geometry. This is illustrated by considering the state diagrams shown in Fig. 4 for a channel that transits between an open and a closed state in a voltage dependent manner, as represented by the rate constants K1(v) and K−1(v). If the closed state “C” forms a Cd2+ binding site, then application of Cd2+ would “drive” the equilibrium to the right, by reducing the rate of channel opening. This would favor channel residency in the closed, Cd2+ bound state C* (Fig. 4A). The decrease in the rate constant of channel opening is determined by the binding affinity of Cd2+ to the coordination site. In macroscopic recordings, such a shift in kinetic equilibrium will result in 1) a decrease in current; reflecting increased channel occupancy in the closed states, and 2) a faster time constant of channel closure in the presence of Cd2+; reflecting stabilization of the closed state by Cd2+. Alternatively, if the open state “O” forms a Cd2+ binding site, then the application of Cd2+ would drive the equilibrium to the left, into the open Cd2+ bound state O* (Fig. 4B). This would result in slowing the kinetics of channel closure in macroscopic recordings. Lock of the channel in a transition state would be expected to slow the kinetics of both channel opening and closure (not illustrated).

Fig. 4.

State diagrams illustrating the effect of Cd2+ coordination on a voltage dependent two state model. (A). Cd2+ coordination to a binding site created only when the channel adopts the closed conformation. Binding of Cd2+ to the site drives the equilibrium to the right, locking the channel in the closed Cd2+ bound state designated at C*. (B) Cd2+ coordination to a binding site created when the channel adopts the open conformation. Binding of Cd2+ to the site drives the equilibrium to the left, locking the channel in the open Cd2+ bound state designated as O*. The rate constants of voltage dependent transitions between the open O and closed state C are represented as K1 (v) and K−1(v). The voltage dependence of Cd2+ block [91] is represented by the term [Cd2+](v). The potential voltage dependence of “unblock” [92] representing the effect of voltage on the stability of bound Cd2+ is represented by the terms Kon(v) and Koff(v).

The local concentration of Cd2+ at the binding site can be voltage-dependent (depicted as [Cd2+](v)), if the site is within the pore and therefore within the voltage field; hyperpolarization would favor Cd2+ entry from the extracellular side, while depolarization would oppose Cd2+ entry (see Woodhull [91]). Thus, a channel closed by hyperpolarization would appear to have a higher affinity for Cd2+ than a channel closed by depolarization, owing to a higher effective concentration of Cd2+ at the binding site than in free solution. The Cd2+ binding affinity itself may also be voltage dependent, in that large voltages may destabilize the binding (coordination) of Cd2+ to the site formed by the cysteine residues. This is conceptually equivalent to “relief” of ionic conductance block by voltage as described by French and Wells [92].

4.2. Metal bridge formation and chemical crosslinking of substituted cysteines in the TM1/E1 segment

Recently, we reported that the loop-gate permeability barrier is formed by the narrowing of the channel pore formed by the segment bounded by residues 40–50 in a chimeric Cx32 undocked hemichannel [56]. This channel, designated as Cx32*Cx43E1 (abbreviated to 43E1), replaces the first extracellular loop (residues 41–70) with the corresponding Cx43 sequence. This chimera expresses membrane currents when not docked to another hemichannel [71]. Channel closure by both the loop-gate and the Vj-gate is favored at inside negative potentials in the 43E1 hemichannel (Fig. 1) but the polarity of Vj-gating can be reversed by placement of a negative charge at the either the 2nd (N2E, see Fig. 2), 4th (T4D) and 5th (G5D) positions [52, 53, 69].

The Cx32*43E1 hemichannel provides several advantages in studies whose goal is to establish conformational changes resulting from voltage-dependent loop and/or Vj-gating by metal bridge formation. Loop-gating and Vj-gating events are readily distinguished. The chimera and polarity reversing mutation N2E have little endogenous sensitivity to Cd2+ (only small reduction in currents are observed when [Cd2+]> 100 µM), in contrast to Cx46 hemichannels, which display substantial reductions in current with 1–10 µM Cd2+ (Kwon and Bargiello, unpublished). The polarity of Vj-gating can be reversed by substitution of negative charge in the NT without large shifts in voltage-dependence (see Fig. 2). Thus, the wild type channel is only closed at negative potentials and fully open at positive potentials, while the N2E channel resides in the open state at voltages around ±20 mV, in the loop-gate closed state at voltages more negative than −20 mV and in the Vj-closed state at voltages more positive than +20mV. Thus, comparisons of Cd2+ bridge formation of cysteine substitutions on wild type and N2E backgrounds allows unequivocal distinction of Cd2+ effects on the open, loop-gate closed and Vj-closed states (i.e. state-dependence). This contrasts the behavior of Cx26 hemichannels, where neutralization of D2 residue to reverse Vj-gating polarity (so that both Vj- and loop-gates close with hyperpolarization) is accompanied by a large inward shift in the conductance–voltage relation [68] such that open probability is ~0.5 at Vj=0 mV. Cx50 hemichannels display bi-polar fast-gating, i.e. fast transitions to substates are observed at both positive and negative potentials, but the channel is fully open in the absence of membrane potential [64]. In this case, studies of conformational changes of loop-gating utilized the differential sensitivity of the Cx50 loop (slow)-gate and fast (Vj)-gate to Ca2+ and K+ to distinguish the two gating mechanisms [34] and infer that Cd2+ formed metal bridges only with loop-gate closure.

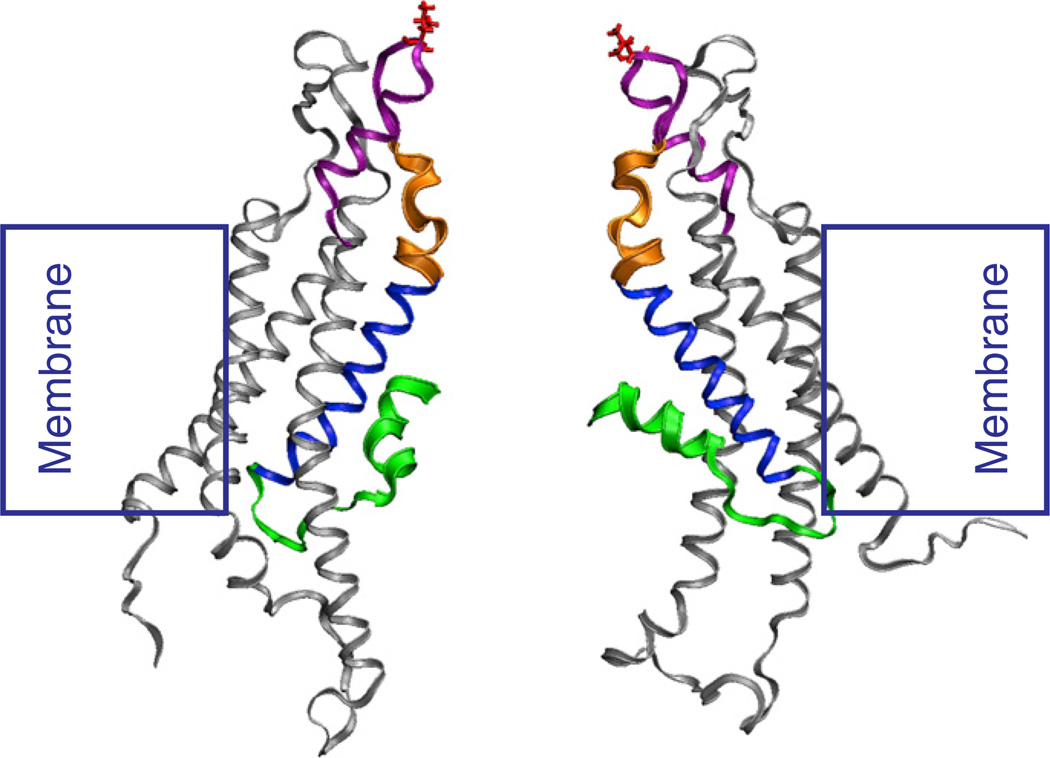

The most significant conformational change with loop-gate closure occurs in the region of the Cx26 channel pore formed by residues 42–51, which contains a small segment termed the 310 helix by Maeda et al. [10]. The structure of a snapshot of the Cx26 hemichannel following equilibration by MD simulations (Kwon et al. [11]) is presented in Fig. 5. The position of the 42–51 segment, whose structure is best described as a parahelix [93] rather than a 310 helix is indicated by thick orange ribbons.

Fig. 5.

Side view showing two opposite subunits of a “snapshot” the Cx26 hemichannel following equilibration by MD simulations [11]. The N-terminus is depicted by the green ribbons, with residues 1–11 shown as thick ribbons. The first transmembrane domain, TM1 is depicted by the thin blue ribbons. The 42–51 segment also termed the parahelix, which contains the 310 helix described by Maeda et al. [10] is depicted by thick orange ribbons. This segment contributes to the formation of the loop-gate permeability barrier in Cx32*43E1 and Cx50 hemichannels. The first extracellular loop (E1) is depicted by the thin purple ribbons. It comprises residues 52–71. The position of the 56th residue, which demarcates the extracellular entrance to the channel pore is colored red.

The effects of Cd2+–Cys metal bridge formation and crosslinking by the homobifunctional reagent dibromobimane (bBBr) on voltage gating of two cysteine substitutions, A40C and A43C were extensively characterized in wild type and N2E backgrounds. In the Cx26 crystal structure, these residues are positioned within a hydrophobic core that includes a network of intra-subunit van der Waals interactions with residues A39, A40, V43, W44 and I74 [10]. Neither cysteine substitution was modified by MTSEA-biotin in single channel recording, indicating that they probably do not line the pore of the open 43E1 hemichannel, in agreement with the Cx26 structure. However, cysteine substitutions of two flanking residues V38 and G45 were modified when the channel resided in the open state, which indicates that these residues line the channel pore. Notably, V38 is not pore lining in the Cx26 crystal structure [10] nor does it have a high probability of pore lining in MD simulations [11]. This result can be explained by either postulating that a small difference in the structure of the open channel exists for Cx26 and 43E1, or that the cysteine substitution causes small conformation changes. Along these lines, it should be noted that the reaction of cysteine residues to MTSEA reagents requires a deprotonated, S−, atom [94]. A charged cysteine residue is expected to prefer the aqueous environment of the channel pore in the absence of suitable countercharge within the transmembrane environment.

Application of µM concentrations of Cd2+ to A43C and N2E+A43C undocked hemichannels channels resulted in state-dependent lock of the channel at voltages that favored channel residency in the loop-gate closed state. Cd2+ had little or no effect on macroscopic conductance at inside positive voltages that favored A43C hemichannel residency in the open state and no effect on N2E+A43C channels at voltage that favor entry into a Vj-closed state. Furthermore, the kinetics of channel closure became faster in the presence of Cd2+. This result is consistent with the stabilization of the loop-gate closed state by Cd2+, which would slow the rate of channel opening at a given voltage (Fig. 4). Application of Cd2+ at hyperpolarizing potentials effectively “drives” the channel into a loop-gate closed conformation. Reversal of the Cd2+-lock of the loop-gate closed state could be accomplished only by application of 5–10 µM of either TPEN (N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine) or DTT (dithiothreitol), known high affinity Cd2+ chelators. The analyses of heteromeric channels containing mixtures of wild type and A43C subunits suggested that at least four A43C subunits were required to produce high affinity Cd2+ binding. These results were interpreted to indicate that the high affinity binding site formed by A43C most likely resulted from the formation of a tetradentate Cd2+ co-ordination site. In parallel and supporting studies, 1 mM bBBr, which cross-links cysteine residues when they are separated by 3.2–6.7 Å, caused an irreversible reduction in A43C membrane currents at voltages that favor loop-gate closure.

Based on these considerations, it was proposed that at least four (but probably all) substituted cysteines at the 43rd locus moved into the 43E1 channel pore on loop-gate closure and that distance separating adjacent thiol groups of the cysteine residues was between 3.5 and 4 Å, depending on the assumption of either an octahedral or tetrahedral coordination geometry involving any four of the six subunits. This interpretation was supported by demonstration of disulfide bond formation by western blots of oocytes expressing A43C hemichannels inserted in the oocyte plasma membrane cultured in 5 mM Ca2+, a condition that favors loop-gate closure. This result was interpreted to indicate that adjacent pairs of cysteine residues could approach to within ~2 Å when the channel was loop-gate closed. Because Cd2+ coordination is a dynamic process, leading to the adoption of the lowest free energy conformation, the ability of adjacent cysteines to approach to within 2 Å is compatible with the formation of tetradendate coordination site. However, it should be kept in mind that Ca2+ could induce a conformational change, as shown by AFM studies discussed above, that may be distinct from the voltage-dependent loop-gate closed state. Nonetheless, it is important to remember that the Cd2+ mediated stabilization of the closed loop-gate driven by voltage is not Ca2+ dependent. Identical Cd2+ lock of voltage-dependent loop-gates is observed when records are obtained in Mg2+ containing Ca2+ free bath solutions and in recording solutions containing low concentrations of divalent cations.

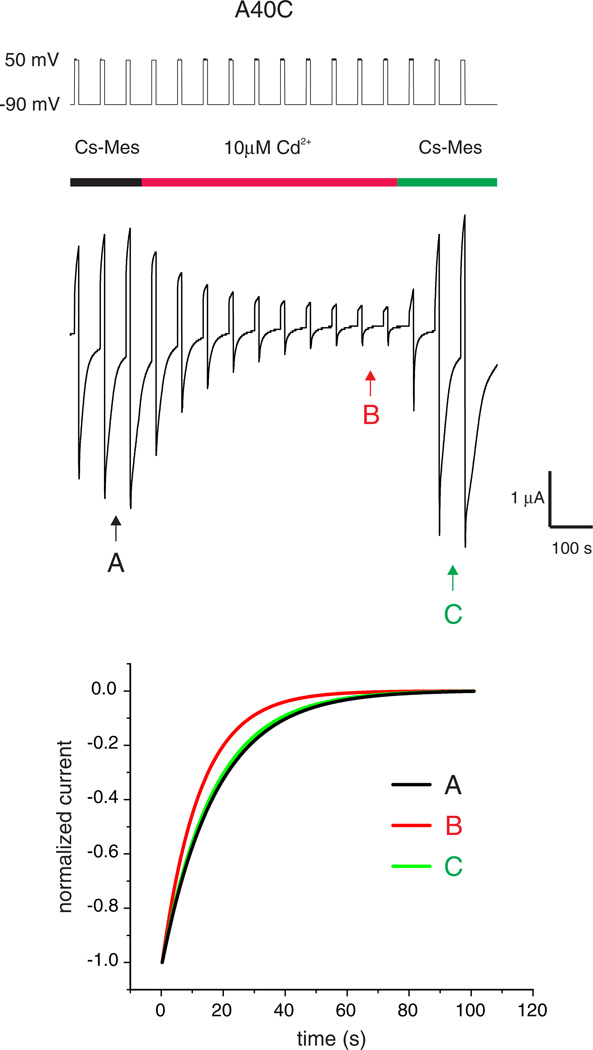

A40C hemichannels could also be locked in the loop-gate closed conformation with 10 µMCd2+. The reduction in current was accompanied by a faster time constant of loop-gate closure, consistent with Cd2+ stabilization of the loop-gate closed state (Fig. 6). However, unlike A43C, for A40C the lock in the closed state was readily reversed by wash with Cd2+ free solutions. The apparent lower affinity of Cd2+ to the cysteine site formed by A40C residues could be explained if A40C channels participate in a bidentate but not a tetradendate interaction with Cd2+. This would occur if the participating cysteine residues were separated by more than the 3.5 to 4 Å required for a tetradentate interaction and coordination with a tetrahedral or octahedral geometry, but ≤5 Å, i.e. 2× the Cd—S bond length required for a less stable bidentate geometry. bBBr also caused an irreversible reduction in A40C membrane currents with hyperpolarization consistent with adjacent cysteine residues being separated by 3.2–6.7 Å in the loop-gate closed state. There was no evidence of disulfide bond formation in A40C channels indicating that the thiol groups do not approach to within 2 Åwhen the channel is closed, unlike for A43C channels.

Fig. 6.

Cd2+ lock of Cx32*43E1 A40C hemichannels is reversed by removal of Cd2+ by wash with bath solution. Current traces elicited by voltage steps from −90 to 50 mV are shown. The time of Cd2+ application is indicated by the red line. Wash with bath solution containing 100 mM cesium methanesulfonate (CsMes), 1.8 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM HEPES pH 7.6 reversed Cd2+ lock. The increase in current at the end of the trace most likely results from the incorporation of new channels into the oocyte plasma membrane during the course of the experiment. Kinetics of channel closure before, during and after Cd2+ application (at A, B, and C respectively) are compared in the lower panel. The time constants of loop-gate closure are faster in the presence of Cd2+ as expected if Cd2+ stabilizes the loop-gate closed state (see text).

Together, these results indicate that closure of the loop-gate involves position 43 in the connexin monomers coming into close proximity. They also suggest that position 40 in the connexin monomers become closer than in the open state, but not as close as position 43.

Recent unpublished results from the Bargiello lab indicate that A50C is modified by MTSEA-biotin-X when the 43E1 hemichannel resides in the open state and that it can be locked in a state-dependent manner by Cd2+ at inside negative voltages that favor loop-gate closure. Q56C, a substituted cysteine located at the extracellular entrance of the channel pore (Fig. 5), does not interact with Cd2+, nor is gating of this mutant altered following bBBr application when it is closed by voltage. Because closure of both Vj- and loop-gates is favored at inside positive potentials, the result indicates that the extracellular entrance of the channel at Q56C does not undergo a large conformational change for either gating process.

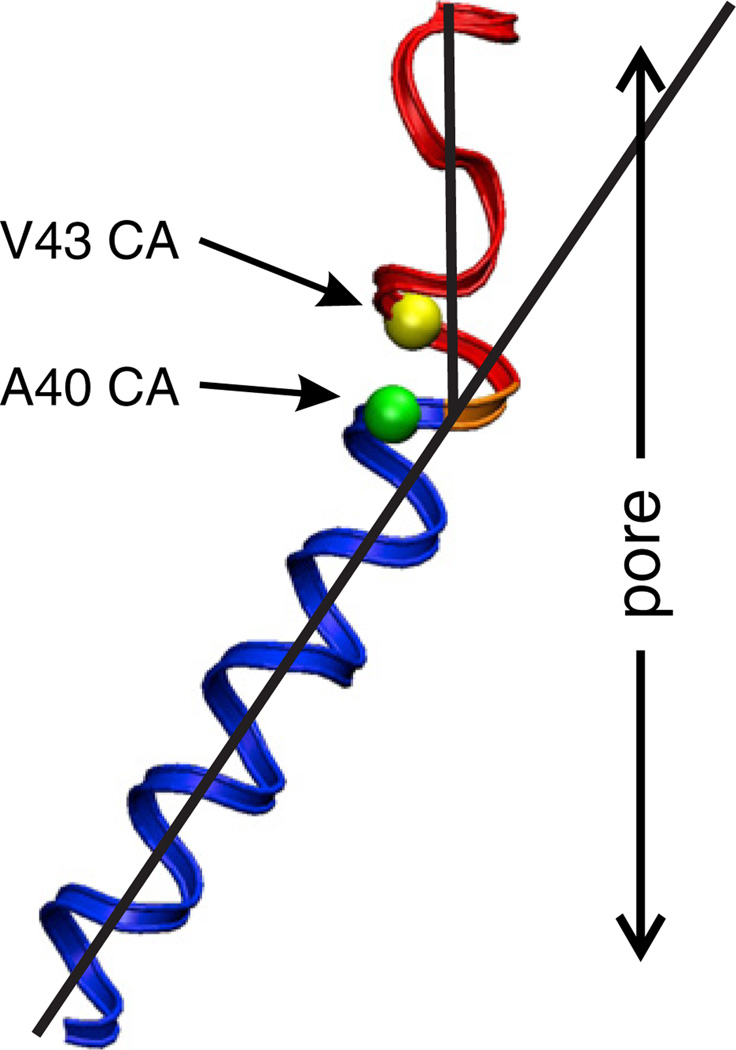

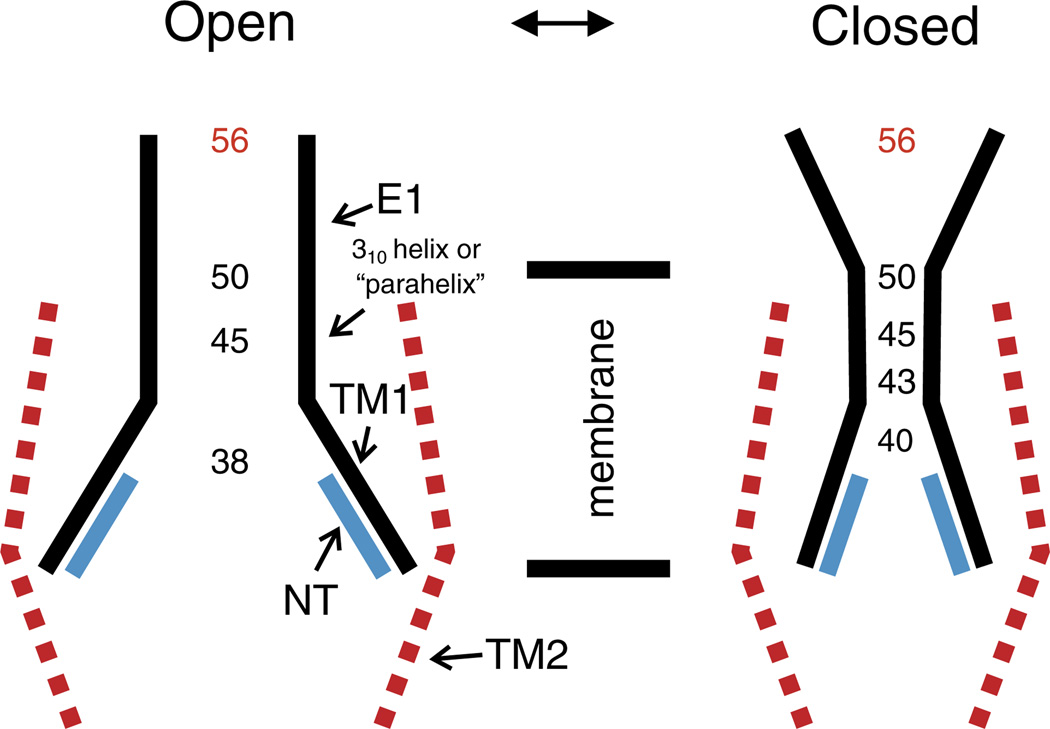

Table 1 summarizes available SCAM, Cd2+–Cys metal bridge formation and crosslinking data for cysteine mutations in the 43E1 hemichannel. Residues depicted in bold are those that interact with Cd2+ in the loop-gate closed conformation. Taken together these results indicate that the segment bounded by residues 43–50 undergoes a substantial conformational change with loop-gate closure. Movement of residues in the segment bounded by the 43rd to 50th loci reduces the channel pore from ~20 Å in the open state to ≤4 Å in the closed state. The data also indicate translocation of the 43rd residue out of the van der Waals network and into the channel pore with loop-gate closure. Notably, this change in the structure of the 42–51 segment, which we define as the parahelix is local, as D50C, which lines the pore of the open channel, also interacts with Cd2+ when the channel is closed by voltage, but the conformational change does not extend to cysteine substitutions of the 56th residues, which demarcates the extracellular entrance to the pore (Fig. 5).We propose that voltage destabilizes the geometry of the parahelix causing it to protrude into the channel lumen. Initially, we had proposed that loop-gate closure might involve an axial rotation of the TM1/E1 domain [56], but this seems less likely from a thermodynamic perspective, as such rotation would require extensive reorganization of van der Waals and electrostatic networks that stabilize the open conformation. The reversible interaction of A40C with Cd2+ (which is consistent with lower affinity bidentate coordination) requires that the distance among adjacent cysteine residues is somewhat larger, ~5.0 Å than those of A43C, 3.5–4 Å,predicted for high affinity tetradentate coordination. Because A40 is located in TM1 on the other side of the TM1/E1 bend where A43 is located (Fig. 7), the data suggest that the conformational change also involves straightening of the TM/E1 bend angle. This would result in narrowing of the intracellular entrance to the channel pore, but it is unlikely that this reduction would fully prevent ion flux. A schematic representation of the open and loop-gate closed state of the 43E1 hemichannel, based on current data, is presented in Fig. 8.

Table 1.

Summary of results for substituted cysteines in the 43E1 hemichannel.

| RESIDUE | Open state modified by MTSEA-biotin X |

DTT/TPEN/TCEP effect on initial current |

Cd2+ effect when channel is open |

Cd2+ effect when loopgate closed | Dibromobimane modification when loop gate closed |

Disulfide bonds in western blots |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V37C | No | None | None | None | Not tested | No |

| V38C | Yes | None | Small decrease reversed by wash | None | Not tested | No |

| A39C | No | None | None | None | Not tested | No |

| A40C | No | None | None | Large decrease, reversed by wash | Yes | No |

| E41C | Low expression not tested | None | Low expression not tested | Low expression not tested | Low expression not tested | No |

| S42C | Low expression not tested | None | Low expression not tested | Low expression not tested | Low expression not tested | No |

| A43C | No | Large increase, but variable between oocytes | None | Large decrease, only reversed by DTT, TPEN, TCEP | Yes | Yes dimers formed |

| W44C | No expression | None | No expression | No expression | No expression | No expression |

| G45C | Yes | Variable | Small decrease reversed by wash | Variable effect between oocytes batches. in some cases moderate to large decrease with partial reversal by wash | Not tested | |

| A50C | Yes | None | Small decrease reversed by wash | Large decrease, partially reversed by wash | Not tested | Not tested |

| Q56C | Labeled by Alexa-Fluor 488 C5-maleimide | None | None | None | None | Not tested |

Mutations that interact with Cd2+ are depicted in bold italics.

Abbreviations: DTT—dithiothreitol; TPEN—N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine; TCEP—tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride.

Fig. 7.

Structure of the TM1/E1 bend angle in a representative Cx26 subunit following equilibration with MD simulation [11]. The positions of the Cα atoms of V43 and A40 are represented by the yellow and green spheres respectively. TM1 is depicted by the blue helix. The segment depicted in red corresponds to residues 41–50, and forms the major part of the loop-gate permeability barrier. The structure shown corresponds to the open channel conformation. In the closed conformation of Cx32*43E1, the geometry of the 41–50 segment changes such that the 43rd and 50th loci move into the channel pore. A40C in 43E1 forms a “lower affinity” Cd2+ binding site, which can be accomplished by straightening the bend angle. The pore diameter formed by the 41–50 segment decreases from ~15–20 to 4 Å in the loop-gate closed state.

Fig. 8.

Schematic representation of the open and loop-gate closed states of a connexin hemichannel, based on studies of conformational changes in the Cx32*Cx43E1 hemichannel. Residues depicted to line the pore of the open channel were determined by substituted cysteine accessibility method using MTSEA-biotin-X as the thiol modifying reagent. The pore diameter in the region of residues depicted in black in the closed model are inferred from the ability of cysteine substitutions at these loci to form metal bridges and/or to be cross-linked by bBBr. The 56th residue is depicted in red to denote that its position does not change substantially with channel closure in either Vj- or loop-gating.

A somewhat different microscopic view arose from studies of metal bridge formation in undocked Cx50 hemichannels [34]. In this study, substituted cysteines of three pore lining residues F43C, G46C and D51C were shown to form Cd2+ binding sites under conditions that favor loop-gate closure. The affinity of Cd2+ binding appeared to be less at D51C than F43C, suggesting that a smaller conformational change occurs at this position. Cd2+ had no effect on gating of A40C and A41C Cx50 hemichannels. (Note that residue numbering of Cx50 is one more than for Cx32*43E1, e.g. A40 in 43E1 corresponds to A41 in Cx50.) Thus, there did not appear to be a local change in helical geometry, although the effect of Cd2+ on gating of the homologous residue Cx50 V44 (43 in 43E1) was not examined. The failure of either A40(39)C or A41(40)C to interact with Cd2+ also suggests a difference in the TM1/E1 bend angle in Cx50 and Cx32*43E1 hemichannels. The TM1/E1 bend angle may not straighten as much in Cx50 as it appears to do in 43E1with loop-gate closure. It is possible that the difference in the conformation of the loop-gate closed state in the two types of hemichannels is related to difference in the organization and strength of the van der Waals networks in the two connexins due to differences in primary sequence. However it is likely that the basic loop-gating mechanism, protrusion of the parahelix (which contains the 310 segment) into the channel pore, is similar if not identical in the two hemichannels.

5. Conformational changes associated with Vj-gate closure

As mentioned previously, the molecular determinants of Vj-/fast gating appear to differ among connexins. Two different mechanisms have been proposed to account for channel entry into substates: conformational changes resulting from movement of a voltage sensor located in the N-terminus as for Cx26 and Cx32 [53, 67, 69] and a particle-receptor mechanism (ball and chain model) for Cx43 and Cx40 where the CT acts as a gating particle by binding to a receptor located in the CL [37, 44, 95]. It should be noted that the original use of the term fast-gating for Cx43 was based on a component of the fast time course of current relaxations (Revilla et al. [44], not the speed of gating transitions as defined by Trexler et al. [51] and Oh et al. [69]). Subsequently, the relation of the fast kinetic component to the fast gating transition of Cx43 and Cx40 into a substate was established by single channel recordings [43, 72, 95]. A comprehensive discussion of the relation between fast and slow gating transitions, voltage dependence and kinetics of current relaxations is presented by Bukauskas and Verselis [13]. It should also be noted that to this date, no studies have demonstrated the operation of the two different fast processes in the same hemichannel. It is possible that the ball and chain mechanism is unique to some channels exemplified by Cx43 and Cx40, while conformational changes initiated by movement of the NT are unique to other channel exemplified by Cx26 and Cx32 channels. It is also possible that the two mechanisms are part of the same process, if for example the conformational change initiated by movement of the NT, exposed the receptor allowing binding of the particle to stabilize the closed state (see below).

Notably, studies of the state-dependence of the loop-gate closed conformation described in the preceding section for Cx32*43E1 and Cx50 hemichannels suggest that conformational changes in the 42– 51 segment do not occur or differ from loop-gate conformations with closure of the Vj-gate [56]. The demonstration that the gating polarity of Vj-gating initiated by movement of the NT of Cx32 channels can be reversed while maintaining the polarity of loop-gating [69] indicates that the two processes (loop and Vj-gating) differ mechanistically, but it does not rule out the possibility that conformational changes may occur in common domains, notably those that form the cytoplasmic entrance to the channel pore. Electrophysiological studies suggested that the pore diameter in the vicinity of the N-terminus of Cx32 is reduced with Vj-closure. This inference was based on the direction of current rectification of intercellular channels, when one hemichannel of the cell pair resides in a Vj-substate [68]. Based on modeling studies performed with solution of Poisson–Nernst–Plank (PNP) equations [96], it was proposed that the substate rectification of Cx32 channels resulted from narrowing the pore diameter in the closed hemichannel that accentuated the effect of positive charge in the cytoplasmic region of the pore. Similarly, in channels whose polarity was reversed by negative charge substitution in the NT, the direction of current rectification was consistent with the narrowing of pore diameter that accentuated the effect of negative charge in the Vj-closed hemichannel. This result was interpreted to indicate that the pore diameter of the channel in the vicinity of the 2nd residue narrowed with Vj closure. We stress that these data do not imply that the NT forms the constriction in Cx32 by itself. Vj-gating could result from larger conformational changes that narrow the cytoplasmic entrance (see [97] for example), consistent with the presence of a large energy barrier separating open and Vj closed states. Similar conclusions were reached in studies of Cx43 intercellular channels [98]. In this case the direction of current rectification could be explained by reduction of channel diameter that accentuated the effect of positive charge in the hemichannel closed to a substate by voltage.

5.1. Role of CT in Cx43 and Cx40 fast gating

An involvement of the CT in a mechanism of Vj/fast-gating has been reported for Cx43 and Cx40 [12, 43, 44, 95]. Studies that implicate a role for CT in are derived from the observation that deletion of the CT at residue 257 or adding tags (such as EGFP) to the CT of Cx43 correlate with the loss of a fast transition to a substate in single channel recordings, but not the slow transition from the fully open to fully closed state (i.e. loop-gating) [44, 72]. The fast voltage-gating mechanism for Cx43 and Cx40 channels invokes a “particle-receptor” (ball and chain) model, which proposes that an interaction between the CT and a region in CL termed L2 mediates the fast gating process. Fast gating of Cx43-CT truncation was reported to be restored by co-expression of Cx43-CT as a separate protein fragment [95], and abolished by addition of the L2 peptide [99] to the wild type channel. Together, these results suggest that the CT is a “freely moving” particle. This model is similar to that proposed to explain pH-gating by Delmar and colleagues [100] in that it invokes the same protein interactions of the CT and CL. It may be significant that Cx43 channels close fully in response to acidification, while to a substate in response to voltage. This suggests that the details of the molecular interactions between the particle and receptor may differ in chemical and voltage regulation of Cx43.

Specific regions of the CT and CL of Cx43 and Cx40 were shown to interact at pH 5.8 by translational diffusion analysis [37] and other biophysical methods [101, 102]. The structure of the peptides corresponding to portions of the CL and most or all the CT of Cx43 and Cx40 have been reported [102, 103]. Both appear to be largely unstructured but it has recently been reported that the CT becomes more structured when linked to TM4 [103]. Mutagenesis of the L2 region (H142E, which is near the CL-TM3border) caused significant reduction in voltage induced occupancy of the substate [37]. Consistent with the interpretation of direct binding of CT and CL-L2 region was demonstration, by NMR, of disrupted structure of the H142E-L2 peptide. The regions of interactions between the CT and CL of Cx43 and Cx40 have been further defined biophysically [102]. Interestingly amino acid residues in the CT that interact with the L2 domain are located much closer to TM4 (in a segment bounded by 265–287 in Cx43) than to the end of the CT (I382), but it has yet to be shown that this in vitro interaction is the basis for the CT/CL interaction in vivo, either directly or indirectly through site directed mutagenesis. There is also evidence to indicate that the end of CT of Cx43 may also bind to L2, but this interaction involves fewer residues [102]. The AFM studies of Liu et al. [42] used antibodies directed against both regions of the CT and demonstrated that CT tail stretching determined with antibodies against the 252–270 segment was less than with antibodies directed against the end of the CT (residues 360–382). These results were interpreted to support the particle-receptor model of Cx43 gating, although it is seems reasonable to expect that a longer peptide segment be more “elastic” than a shorter segment if there is any secondary structure.

A major unanswered question, relevant to establishing the mechanism of reduction of current flux, is the position of L2 (the receptor) relative to the channel pore. If L2 lies within the channel pore, then the particle could block ion conductance by entering into the pore and binding the receptor (voltage-dependent block). If L2 lies outside the channel pore, then it is likely that voltage and/or pH causes a conformational change that exposes the receptor. In this case the “particle” would likely interact with the receptor to stabilize the “closed” conformation (i.e. increase the closed probability).

It is possible that L2 is located near or in the channel pore, as the cytoplasmic entry of the Cx26 channel is formed by the tip of TM2 at the junction of the CL (Fig. 5). However, it should be kept in mind that the structure of the Cx43 CL and its relation to the channel pore has not been determined [104], and in the primary sequence of Cx43, most of the L2 region is positioned in the second half of the CL, closer to TM3, which in the Cx26 structure lies at some distance from the channel pore (see [105] and Fig. 5).

Several features of the particle receptor model need further investigation. There is no simple explanation for the large energy barrier that appears to separate open and closed states in a “ball and chain” type of model. The binding of a freely mobile gating particle formed by a protein domain adopting a highly flexible extended conformation to a binding site near the cytoplasmic entrance to the pore is not expected to encounter significant energy barriers, particularly if the pore diameter of Cx43 is comparable to the large pore diameter of Cx26 hemichannel (~35–40 Å) at the intracellular entrance [10, 11]. The apparent long-time constant of current relaxation could reflect the probability that a gating particle finds its binding site, however the presence of 6 CT domains would suggest that this is not rate limiting. It has been estimated that the effective concentration of CT near the cytoplasmic entry could be as high as ~25 mM [102]. The number of CT subunits that interact with CL domain to effect entry into the substate has not been determined. It should also be kept in mind that a gating particle moving freely in the cytoplasm located at some distance from the channel pore is not expected to move in response to a voltage field, as the cytoplasm is equipotential at distances beyond a Debye length from the membrane or the protein surface (see [106]). Its movement will be largely diffusion limited if the CT is flexible and highly mobile as suggested by NMR. Also, it should be noted that the steepness of voltage-dependent block reflects the fraction of the electric field that is crossed by a gating particle of a given valence [91] when it binds its “receptor”. In general terms, the voltage dependence of a blocking particle of given valence will be less steep if the binding site is close to the cytoplasmic entrance of the channel than if it lies deeper inside the channel pore. If the site of the CT/CL interaction (L2) is in the channel pore, close to the cytoplasmic entrance, then the voltage-dependence of the fast process would primarily reflect the valence (net charge) of the gating particle. This should be positive based on the polarity of fast voltage dependence.

If the receptor contained in L2 is not pore lining, then the observed voltage-dependence would most likely correspond to the voltage-dependence of a conformational change that exposes L2 allowing binding of the particle. In this case the energy barrier would primarily correspond to that of the conformational change that exposes the relevant amino acids in L2. The binding of the particle to the receptor would be independent of voltage, as there is no substantial voltage drop across the cytoplasm and it would not be expected to traverse a large energy barrier if it is freely mobile in the cytoplasm.

A similar role in fast-gating has been proposed for the CT of Cx32 [44] based on changes in closing kinetics of macroscopic conductance of Cx32 gap junctions. A Cx32-CT truncation (at residue 220) was reported to alter the kinetics of channel closure, reducing or removing a fast component of current relaxations of these gap junctions evident within the first 100 ms of a 5 s current trace. However the effects on the kinetics of Cx32 current relaxations were not large. The kinetics of the current relaxations of the remaining “slow” component of the truncation were faster than wild type and may have obscured the detection of the fast event observed in wild type channels. The operation of the proposed “ball and chain” mechanism in voltage-gating of Cx32 awaits confirmation by demonstration of loss of Vj-gating by single channel recordings of truncation mutants and knowledge of the location of the receptor relative to the channel pore.

The short length of the Cx26 CT (10 residues) and its distance from the channel pore argues against a mechanism in which it functions as a gating particle by interactions with the CL to block the channel pore. However, there is evidence suggesting that the CL and CT of Cx26 interact [105, 107], although no role for this interaction has been postulated in voltage-gating. Vj-gating of Cx26 gap junctions, like Cx32 junctions is characterized by entry into different subconductance states [68], rather than into a single substate as described for Cx43, which could be ascribed to the entry of a single Cx43 CT into the channel pore. The entry of Cx26 channels into multiple substates suggests that a long CT is not required for this aspect of gating behavior. Notably, truncations of the CT of Cx46, a connexin with long CT and CL domains, do not alter or abolish Vj (fast) gating (i.e. closure at depolarizing potentials) in macroscopic recordings of hemichannels expressed in Xenopus oocytes ([108] and also Kwon and Bargiello, unpublished observations). This suggests that the particle-receptor gating mechanism may not operate in all connexin channels, but additional studies are required. The central question is whether the particle acts as a “blocking” particle, or if it stabilizes a closed state, following exposure of the L2 receptor as part of a larger conformational change initiated by voltage.

5.2. Role of the N-terminus

The role of the N-terminus in determining the polarity of Vj-gating in Cx32 and Cx26 hemichannels is well established [52, 53, 67, 69] and makes clear that the N-terminus comprises at least a portion of the voltage sensor, but these studies of gating polarity do not define the conformational change associated with entry into substates. Little information derived from electrophysiological studies of Vj-gating can be used to directly inform the conformation of Vj-closed state. As mentioned previously, the rectification of currents through substates reported in Cx32 intercellular channels suggests that the intracellular entrance in the vicinity of the NT narrows with Vj-gate closure. Studies using metal-bridge formation and chemical crosslinking have the potential to define the structure of the Vj-closed state.

A role for the NT in voltage gating has been suggested in other connexins. Charge neutralization at the D3 position in Cx46 and Cx50 hemichannels appear to reverse the polarity of Vj-gating [64, 109]. The Cx50 study [109] was based on the asymmetry of the conductance–voltage relation of the heterotypic junction, Cx50/Cx50D3N, with closure observed for a single polarity of Vj, but the results need to be confirmed by single channel recording, as it has been reported that wild type Cx50 hemichannels display bi-polar fast gating events in single channel recordings [64]. Other studies have established a role of the N-terminus in gating and permeation [110–112].

The critical feature of Cx26 and Cx32 channels is the location of the NT within the channel pore, as in this position it can sense changes in Vj. It was proposed that the positioning of the Cx26 and Cx32 N-termini within the pore depends on the formation of a flexible open turn initiated by the conserved G12 residue in these group 1 or β connexins [113, 114]. This prediction is consistent with the Cx26 crystal structure. However, it should be noted that an NMR study has shown that the solution structure of a Cx37 NT peptide (a group 2 (α) connexin) differs from that of Cx32 and Cx26 in lacking a flexible open turn at the 12th position [110, 113, 114]. It is unclear how the NT of Cx37 is positioned in the channel pore. Furthermore, studies have shown that the N-terminal Met residues of Cx46 and Cx50 native hemichannels are cleaved and the penultimate glycine residue acetylated [115]. This co-translational charge modification, which neutralizes the positive charge of the N-terminal amine and the potential structural differences in the NT could play a significant role in determining both Vj-gating and ion permeation of group 2 (α) connexins. The N-terminal amine of Met1 has been shown to be acetylated in Cx26 [116], a modification that is expected to increase the electrostatic effect of the D2 residue (see Kwon et al. [11]), which has been shown to determine the gating polarity of Cx26 hemichannels [67]. Notably at least a fraction of Cx32 N-termini of Cx32 proteins are not acetylated as N-terminal sequence is obtained with the Edman degradation method [117, 118]. Acetylation blocks the N-terminus in this sequencing method. Thus, it is unclear where the positive charge required for the polarity of wild type Cx32 Vj-gating [67] is located. It may involve partial charges resulting from the dipole moment of neutral residues. Notably, all neutral and positive charge substitutions of the second Asn residue of Cx32 maintain wild type gating polarity, as do positive charge substitutions at the 5th and 8th positions [53, 67]

The studies of Oh et al. [53, 69] reveal several aspects of Vj-gating in Cx32*43E1 and N2ECx32*43E1 hemichannels that must be kept in mind when considering the mechanism of Vj-gating initiated by the NT and possible underlying conformational changes. These include:

The demonstration that closure of Vj-gates can result from conformational changes in individual subunits, rather than by a “concerted” mechanism in which all 6 subunits adopt the closed conformation together.

That the movement of a single subunit can result in channel occupancy in more than one substate. This is demonstrated by the entry of heteromeric hemichannels containing a single N2E subunit into at least 3 different substates at positive potentials. This closure can be attributed to gating initiated by the single N2E subunit. Thus, the appearance of multiple substates in the closure of the Vj gate is not necessarily a consequence of different conformations arising from the movement of multiple subunits, but rather, it strongly suggests that any one subunit can adopt different “stable” closed conformations.

Several 43E1 homomeric hemichannels containing charge substitutions in the N-terminus display bi-polar Vj-gating, defined as the decrease in open probability at both inside positive and negative voltages with open probability maximal at 0 mV [52, 53]. These include, T8D, N2E+G5K, N2R+G5D. The molecular basis of bipolar channels is best explained by modeling the Vj-voltage sensor as a center open toggle switch [53]. In this model, either the inward or outward movement of the voltage sensor initiates channel closure. The voltage sensor in a bi-polar channel would cross one energy barrier for one polarity of voltage and the other barrier for the opposite polarity of voltage. Interestingly, the voltage sensitivity of bipolar channels correlates with the sign of the charge at the 2nd residue, suggesting that charges at this position may have a larger role in determining gating polarity [53]. This suggests that a larger fraction of Vj drops over the 2nd than 5th residue in the double mutations.

The long time constant of Vj-gating of the N2E43E1 hemichannel depicted in Fig. 2 suggests that the open and closed states are separated by a large energy barrier. Because channels are fully open at voltages around 0 mV, the free energy of the open state is much lower than that of the Vj-closed states. This indicates that voltage acts to destabilize the structure of the open state and to stabilize the structure of the closed states.

5.3. Gating plug model of Cx26 Vj-gating

A recently proposed model of Vj-gating [10] was based on the crystal structure of Cx26 and an electron microscopy study that showed the formation of a plug in the pore of the Cx26 mutation M34A [45, 46]. The Cx26 M34A mutation forms channels in which the open probability is low at 0 mV. Thus, it is expected to adopt a closed channel state during preparation for EM imaging. The Vj-gating model proposed is also based on the high mobility of the N-terminus (indicated by the temperature factors determined for the crystal and in MD simulations of the Cx26 hemichannel [11]) and the stabilization of the position of the N-terminus in the crystal structure by 1) an inter-subunit hydrogen bond formed between the side chain of D2 and backbone amide of T5 and 2) a van der Waals interaction between W3 and M34A. It was proposed that voltage initiates Vj-gating by breaking the inter-subunit hydrogen bonds by the inward movement of the D2 residue (i.e. toward the cytoplasm). This movement would presumably lead to the destabilization of the NT leading to the loss of the W3–M34 interaction. The net result is the movement of the N-terminus to a position that would partially occlude the channel pore. Partial occlusion is required to account for the existence of sub-conductance states with Vj-gating. The movement of all six subunits would result in formation of a gating plug as predicted by the structure of the M34A. Supplementary Fig. 10 in Maeda et al. [10] depicts an outward movement of D2 (i.e. into the channel pore) in response to positive voltage, however, their text states that D2 moves inward (towards the cytoplasm) in response to positive voltage.

However, a recent study of the functional properties of Cx26M34A channels by Oshima et al. [47] led to the conclusion that the closed state of Cx26M34A differs from that induced by trans-junctional voltage. This brings into question the model of Vj-gating in which the closed state adopts the conformation of the M34A mutation. However, the strategy to determine the structure of the voltage-gated closed state(s) may be possible with mutations that are known to cause large shifts in the voltage-dependence of Cx26 and these may define the structure of the Vj-closed state.

A potential difficulty with the gating plug model is the stability of the closed state. The concern is whether the six subunits that form the gating plug could dissociate by thermal energy alone (to reopen the pore) as required by the loss of an electrical driving force when Vj is returned to 0 mV. Recall that voltage acts to stabilize the closed stated and the Vj-gates are fully open in the absence of applied potential. Although the structure of the gating plug is not known at atomic resolution it seems likely that the structure will prove to be stable owing to potential formation of extensive inter-subunit interactions of non-polar residues comprising the N-terminus.

5.4. Role of role of a proline kink motif in TM2

The model of Vj-gating based on structure–function analyses and Monte Carlo computer simulations of the behavior of a proline kink in TM2 [97] (see also [119]) runs into difficulties when considered in terms of the Cx26 crystal structure. It was proposed that the straightening of the bend angle formed at P87 (proline-kink motif) by the destabilization of a side chain backbone hydrogen bond (the TP motif) led to channel closure. However, consideration of the direction of the TM2 bend in the crystal structure indicates that a decrease in the bend angle would increase the diameter of the intracellular entrance of the channel pore. Thus, the simple mechanism proposed [97] should be re-evaluated in terms of the structure and dynamic interactions of the N-terminus with TM2 in the Cx26 hemichannel.

6. Molecular dynamics simulations of the Cx26 hemichannel

Elucidation of the mechanisms of voltage-gating at the atomic level requires accurate molecular models of the open and closed states. All-atom MD simulations of the crystal and “completed” Cx26 hemichannel (which includes atoms not defined in the crystal structure) in an explicit solvated POPC membrane system [11] followed by computation of ion permeation with grand canonical Brownian Dynamics GCMC/BD simulations [120–122] indicate that it is unlikely that the crystal structure is that of the biologically active open channel. Consequently, functional inferences based on the assumption that the crystal structure represents the open channel should be interpreted cautiously.