Abstract

Objective

To establish the empirical evidence base for the information that participants want to know about medical research and to assess how this relates to current guidance from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES).

Data sources

Medline, Web of Science, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Sociological abstracts, Health Management Information Consortium, Cochrane Library, thesis index's, grey literature databases, reference and cited article lists, key journals, Google Scholar and correspondence with expert authors.

Study selection

Original research studies published between 1950 and October 2010 that asked potential participants to indicate how much or what types of information they wanted to be told about a research study or asked them to rate the importance of a specific piece of information were included.

Study appraisal and synthesis methods

Studies were appraised based on the generalisability of results to the UK potential research participant population. A metadata analysis using basic thematic analysis was used to split results from papers into themes based on the sections of information that NRES recommends should be included in a participant information sheet.

Results

14 studies were included. Of the 20 pieces of information that NRES recommend should be included in patient information sheets for research pooled proportions could be calculated for seven themes. Results showed that potential participants wanted to be offered information about result dissemination (91% (95% CI 85% to 95%)), investigator conflicts of interest (48% (95% CI 27% to 69%)), the purpose of the study (76% (95% CI 27% to 100%)), voluntariness (39% (95% CI 2% to 100%)), how long the research would last (61% (95% CI 16% to 97%)), potential benefits (57% (95% CI 7% to 98%)) and confidentiality (44% (95% CI 10% to 82%)). The level of detail participants wanted to know was not explored comprehensively in the studies. There was no empirical evidence to support the level of information provision required by participants on the remaining seven items.

Conclusions

There is limited empirical evidence on what potential participants want to know about research. The existing empirical evidence suggests that individuals may have very different needs and a more tailored evidence-based approach may be necessary.

Article summary

Article focus

What information do potential participants want to know when they are deciding whether to take part in research?

What is the established empirical evidence base?

How does the current empirical evidence base relate to current guidance from the NRES?

Key messages

There is little empirical evidence of what information potential participants want to know about research when they are making the decision to take part.

The limited empirical evidence available suggests that potential participants may have very different information needs.

Further research is required to determine what potential participants really want to know about research and how this can be delivered in a way that takes into account their different informational needs.

Strengths and limitations of this study

An extensive search strategy ensured that the review was systematic in capturing all available empirical evidence.

Papers included in the review differed in their methodologies and presentation of results, making comparisons between papers extremely difficult.

Introduction

Medical research is central to the advancement of treatments, services and technology.1–3 Potential participants have the right to choose whether they participate in medical research,4 5 and individuals must give their consent prior to participating in research. As part of this ongoing process, potential participants must be provided with sufficient information to make a voluntary and informed decision.2 6–11 In research settings, study information is usually conveyed to potential participants in the form of a written participant information sheet (PIS), which is later reinforced by a verbal consent interview with a member of the research team.12

In the UK, the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) provides extensive guidance on how a PIS should be written and presented. The guidance suggests that a PIS should be split into two parts where part one provides a brief and clear explanation of the essential elements of the specific study and allows participants to make an initial choice of whether the study is of interest. Part two should then contain additional information on matters such as confidentiality, indemnity and publication intentions.

There is some concern that PIS have become increasingly lengthy over recent years.10 13 14 Complex studies, for example, where the potential participant might, for example, on the basis of test results be invited to participate in a further phase of the study, often use detailed and lengthy PISs. This can lead to poor understanding by participants15–17 and a corresponding concern that consent criteria are not always met. The NRES guidance is not explicit in the level of detail to be included in a PIS, and there is disagreement among experts about how much information to include.18 If PISs become so complex that only the most confident and educated participants are able to digest all the information, this may result in selection bias meaning that research is less generalisable.19 Furthermore, there is a risk that healthcare researchers are becoming increasingly paternalistic in their information provision without recognising individual participant needs. In order to help address the problem of how much information to include in PIS, we conducted a systematic review that aimed to establish the empirical evidence base for the information that potential participants want to know when they are deciding about participation.

Methods

Selection criteria and literature search

This systematic review included all studies that asked participants to indicate how much or what type of information they wanted to be told about a research study or asked them to rate the importance of a specific piece of information. We included studies published between 1950 and 27 October 2010 with no limit to language or participant group. We only included studies of participant opinion and excluded studies of healthcare professional or other expert opinion.

We combined Mesh terms Patient, Research Subjects, Consent forms, Informed Consent and Research ethics with terms relating to information provision (online appendix 1). We conducted searches in Medline, Web of Science, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Sociological abstracts, Health Management Information Consortium and the Cochrane Library electronic databases. We also searched thesis index's, grey Literature databases, reference and cited article lists, key journals and Google Scholar and we asked expert authors to identify relevant studies.

We did not conduct a formal quality assessment of included literature because there were both quantitative and qualitative studies, widely varied study methods and different types of results that were often not comparable between papers. Instead, we conducted a critical appraisal of each paper using five quality indicators (response rate, sample size, demographics, participant characteristics and strengths and limitations of study methods). The strengths and limitations of each study are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the systematic review

| Lead author/country/year | Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Participant illness | Participant demographics | Total number of participants (response rate) | Study design | Sampling strategy | Analysis | Key themes explored | Study strengths | Study limitations |

| Walkup,20 USA, 2009 | None provided | None | Gender: not reported | 57 (not provided) | Exploration of conversation and questionnaire | Convenience | Descriptive summary statistics | Study purpose, voluntariness, study method, risks, benefits, confidentiality and review board approval |

|

|

| Age: not reported | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: not reported | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: not reported | ||||||||||

| Bento,21 Brazil, 2008 | Female participants aged 18–49 years who had taken part in a clinical trial of women's health in the previous 12 months and lived in Metropolitan area of Campinas, Sao Paulo, Brazil | Women's health | Gender: only female |

|

Focus groups | Convenience | Framework analysis | Study methods, risks and benefits |

|

Demographics not representative of the general population as the study only included women and was limited to participants from a trial of a contraceptive intervention |

| Age: 18–49 | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: 4 focus groups 8th grade or less, 4 focus groups above 8th grade education | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: not reported | ||||||||||

| Hutchinson,7 Australia, 1996 | Participants of clinical trials of COPD, asthma, diabetes, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis and the influenza vaccine. Excluded if clinical trial for acute, life-threatening or debilitating conditions with inadequate therapy | Chronic illness | Gender: 52% male | 259/324 (80%) | Questionnaire | Convenience | Descriptive summary statistics and multivariate logistic regression | Conflicts of interest (CoI)/organisation and funding of the research | Demographics not representative of the general population as median age 70 | |

| Age: median age 70 (range not reported) | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: range of backgrounds | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: not reported | ||||||||||

| Gray,22 USA, 2007 | Participants enrolled onto a phase I research trial, spoke English and were medically and mentally capable of participating | Phase I research trial | Gender: 52% male | 102/119 (86%) | Questionnaire | Consecutive participants enrolling onto parent trial | Descriptive summary statistics, χ2 tests and multivariate logistic regression | CoI/organisation and funding of the research | Same interviewer conducted all interviews | Demographics not representative of the general population as the median age was 61 and was limited to cancer patients participating in an early phase clinical trial |

| Age: median age 61 (range 26–82) | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: range of backgrounds | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: 81% white | ||||||||||

| Fernandez,23 Canada, 2007 | English-speaking adolescent with cancer or parents of children with cancer. Excluded acutely unwell or recently relapsed | Cancer |

|

40/43—10 adolescent, 30 parent participants (93%) | Questionnaire | Random | Descriptive summary statistics and χ2 tests | Return of study results | Demographics not representative of general population as participants were well educated, mostly Caucasian and limited to adolescents with cancer/parents of children with cancer | |

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Bento,33 USA, 2006 | Participants of HIV, hepatitis, arthritis and surgical oncology trials who were >18 years and English speaking | Various | Gender: 61% male | 33 (not provided) | Face-to-face semi-structured interviews | Convenience | Transcripts coded and themes and major concepts identified | CoI/organisation and funding of the research |

|

|

| Age: not reported | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: range of backgrounds | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: 70% white | ||||||||||

| Hampson,24 USA, 2006 | Participants with cancer and enrolled in a clinical trial who were English speaking and >18 years | Cancer | Gender: 56% male | 252/272 (93%) | Structured face-to-face interviews | Not provided | Descriptive summary statistics and Fishers exact test/Kruskal–Wallis test | CoI/organisation and funding of the research | Validated interview questions | Demographics not representative of general population as the study population were well educated, financially secure and limited to adult participants of a clinical trial |

| Age: 24%, <50; 32%, 50–59; 26%, 60–69; 16%, >70 | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: well educated and financially secure | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: 92% white | ||||||||||

| Weinfurt,25 USA, 2006 | Healthy adults or those with a mild chronic illness. Excluded if they had participated in another focus group within the previous 6 months or were working or had worked for an organisation involved in the conduct of clinical trials | Healthy | Gender: 42% male | 16 focus groups (not provided) | Focus groups | Convenience | Initial content codes based on transcripts developed that were summarised and reviewed to identify main themes | COI/organisation and funding of the research | Participants not limited to disease group |

|

| Age: 12%, 18–29; 51%, 30–49; 37%, >50 | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: well educated and financially secure | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: 56% white | ||||||||||

| Partridge,26 USA, 2005 | All participants of the parent trial (chemotherapy trial) | Cancer | Gender: only female | 94/135 (69.6%) | Questionnaire | Convenience | Simple descriptive statistics | Return of study results |

|

|

| Age: mean age 55 (range not reported) | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: range of backgrounds | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: 96% white | ||||||||||

| Kim,27 USA, 2004 | Potential research participants >18 years, diagnosed with heart disease, breast cancer or depression and listed on the Harris Interactive Chronic Illness Database | Various | Gender: 50% male | 5478/20205 (27%) | Online questionnaire | Random | Two-way ANOVA modified for ordinal data and multinomial logistic regression | CoI/organisation and funding of the research |

|

Demographics not representative of general population as it was limited to internet users |

| Age: 4% 18–29, 16% 30–44, 61% 45–64, 19% 65+ | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: range of backgrounds | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: 92% white | ||||||||||

| Partridge,28 USA, 2003 | Any participant enrolled into the parent study (chemotherapy trial) | Breast cancer | Gender: not reported | 51/55 (93%) | Questionnaire | Convenience | Simple descriptive statistics | Return of study results | Multicentre |

|

| Age: median age 54 (range 29–82) | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: range of backgrounds | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: 84% white | ||||||||||

| Casarett,29 USA, 2001 | Participants with a current telephone number, enrolled at a pain clinic, who had chronic non-malignant pain, were taking scheduled opioids and had experienced the pain for at least 6 months | Chronic pain | Gender: 40% male | 40/86 (46.5%) | Semi-structured telephone interviews | Convenience | Descriptive summary statistics and bivariate analysis with non-parametric tests | Voluntariness, study methods, expenses, risks and the drug/device/procedure being tested |

|

Demographics not representative of general population as participants were more often men and limited to chronic pain patients |

| Age: mean age 47 (range 30–86) | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: range of backgrounds | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: 85% white | ||||||||||

| Maslin,30 UK, 1994 | Attending a breast unit and were patients with a breast cancer diagnosis or asymptomatic women with a family history of breast cancer | Cancer | Gender: only female | 213/300 (71%) | Postal questionnaire | Random | Simple descriptive statistics | Study purpose, voluntariness, study methods, risks, benefits and confidentiality | Participants chosen at random but from a subset of those attending a breast unit | Demographics not representative of general population as the study only included women and was limited those with breast cancer |

| Age: median 47 (range 24–81) | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: not reported | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: not reported | ||||||||||

| Sand,31 Norway, 2008 | Participants eligible for the parent study (all lung cancer patients) | Cancer | Gender: 57% male | 21/33 (64%) | Semi-structured interviews | Convenience | Identification and categorisation of themes and analysis based on deductive and inductive categories | Voluntariness, study methods and treatment alternatives |

|

|

| Age: median age 69 (range 44–84) | ||||||||||

| Education/deprivation: range of backgrounds | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity: not reported |

Data extraction and synthesis

One researcher (HMK) extracted data from papers using a pre-defined data extraction sheet and a second researcher (TK) checked it for accuracy with disagreements resolved by discussion between these two authors (table 1). A metadata analysis using basic thematic analysis was used to analyse the data from the 14 papers. Themes were based on the sections of information that NRES recommends should be included in a PIS (table 2).10 Each paper was assessed to identify any further themes relating to what information research participants may want to know. A metadata analysis coded individual results based on their relevance to each theme and then themes were collated to report overall results. For themes where more than one quantitative study reported a proportion of participants wanting to know the information, pooled proportions with random effects were calculated using StatsDirect statistical software (StatsDirect Ltd).

Table 2.

Empirical evidence linked to NRES participant information sheet recommended headings

| NRES Heading | What does NRES say should be included? | Number of studies | Empirical evidence for inclusion in PIS from literature |

| What is the purpose of the study? | Purpose is an important consideration for subjects and should be included | 223,32 | Pooled results showed that 76% (95% CI 27% to 100%) participants wanted to know about study purpose |

| Why have I been invited? | Why and how participants have been chosen and how many will be in the study | 0 | No empirical evidence |

| Do I have to take part?/What will happen if I don't want to carry on with the study? | The voluntary nature of the research should be included | 421–23,32 | |

| What will happen to me if I take part?/What will I have to do? | How long the participant will be involved in the research/how long the research will last | 321,23,32 | Pooled results from all three studies20,29,30 showed that 61% (95% CI 16% to 97%) participants wanted to know how long the research would last |

| How often they need to attend a clinic | 121 | 68% (27/40; 95% CI 53% to 82%) wanted to know the frequency of additional study visits29 | |

| How long visits will be | 0 | No empirical evidence | |

| Exactly what will happen to them | 221,22 |

|

|

| Expenses and payments | Expense claims available and if there is any kind of payment for participation | 121 | 25% (10/40; 95% CI 11.6% to 38.4%) wanted to know if free medication would be available during or after trial29 |

| What is the drug, device or procedure that is being tested? | Short description of the drug, device or procedure and given the stage of development state the dosage of the drug and method of administration, and details of any contraindicated drugs included over the counter drugs | 221,31 |

|

| What are the alternatives for diagnosis or treatment? | What other managements/treatments are available and a list of all important comparative risks and benefit | 122 | 5% (1/21; 95% CI 0% to 13.9%) wanted as much information about treatment alternatives as they received about the study medication31 |

| What are the possible disadvantages and risks of taking part?/What are the side effects of any treatment received when taking part? | Any risks, discomforts or inconvenience should be outlined | 416,23,31,32 | Specific information types varied considerably between studies so no meaningful pooled results could be calculated. Results ranged from no participants that asked about study risks (0/57)20 to 97% (207/213; 95% CI 95% to 99.4%) who wanted to be informed about any possible emotional or physical discomforts and side effects30 |

| Radiation and the Ionising Radiation Regulations | If the use of additional ionising radiation is required as part of the study, then information must be given to the participant on the radiation involved | 0 | No empirical evidence |

| Harm to the unborn child: therapeutic studies | Clear warnings must be given where there could be harm to an unborn child, if there was a risk in breast feeding or if taking the medication is likely to cause fertility problems | 0 | No empirical evidence |

| What are the possible benefits of taking part? | Benefits should be included, but where there is no intended clinical benefit it should be stated clearly | 323,31,32 |

|

| What happens when the research study stops? | Arrangements for after the trial finishes must be given, and it must be clear if participants will have continued access to any benefits or intervention they may have obtained during the research. If treatment will not be available after the study, it should be explained what treatment will be available instead | 121 | 55% (22/40; 95% CI 39.6% to 70.4%) wanted to know about the availability of medication after the study was over29 |

| What if there is a problem? | How complaints will be handled and what redress may be available | 0 | No empirical evidence |

| Will my taking part in the study be kept confidential? | How data will be collected, stored, what it will be used for, who will have access to it, how long it will be retained for and how it will be disposed of | 223,32 | Pooled results showed that 44% (95% CI 10% to 82%) participants wanted to be given information about confidentiality and the protection of their privacy |

| Involvement of the GP/family doctor | If the participants GP needs to be notified of involvement or asked for consent | 0 | No empirical evidence |

| What will happen to any samples I give? | Clear description of whether new samples will be taken, if excess samples will be taken, and if access to existing stored samples will be required. The same type of information as for data is required to be provided | 0 | No empirical evidence |

| Will any genetic tests be done? | A separate consent form for genetic studies should be used | 0 | No empirical evidence |

| What will happen to the results of the research study? | What will happen to the results of the research, if it is intended to be published and how results will be made available to participants and that they will not be identified in any publication | 328,30,33 |

|

| Who is organising and funding the research? | The organisation or company sponsoring the research and funding the research if these are different and if the researcher conducting the research is being paid | 620,24–27,34 |

|

| Who has reviewed the study? | Explain the role of the research ethics committees and which committee reviewed the current study | 123 | No participants asked about institutional review board approval (0/57)20 |

GP, general practitioner; NRES, National Research Ethics Service; PIS, participant information sheet.

Results

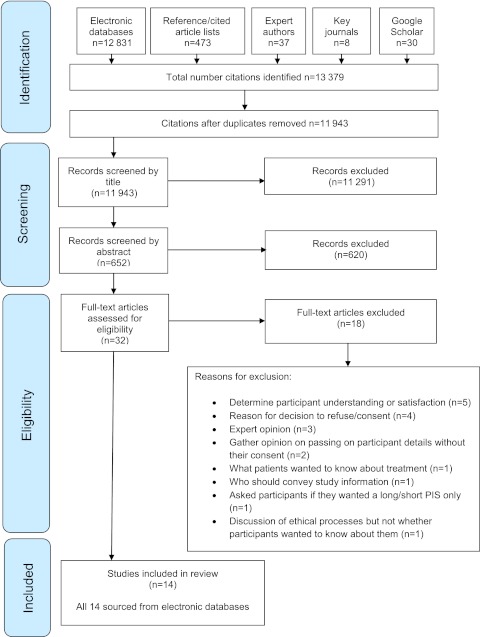

The search yielded 11 943 unique references. We discarded 11 291 after reviewing the title, 620 after reviewing the abstract and a further 18 after reviewing the full paper (figure 1). HMK conducted the citation screening and TK independently validated approximately 10% of the references identified from electronic databases (96.0% κ agreement rate). All 14 included studies were identified from searches of Medline and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts. Expert authors identified 37 unique references; 13 were duplicates from the electronic searches and 24 did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Results of search strategy and identification of publications included in the review.

Of the 14 studies included in the review, three specifically considered the return of research results to participants and six considered only investigator conflicts of interest. Five studies looked broadly at what information potential research participants wanted to know.

Of the 20 sections of information NRES suggest should be included in a PIS, there were seven categories where no empirical evidence was identified that suggested what information research participants wanted to know (table 2). No further themes, beyond the NRES categories, were identified. We were able to calculate pooled proportions for seven themes. Participants wanted to be told about dissemination of study results (91% (95% CI 85% to 95%)), investigator conflicts of interest (48% (95% CI 27% to 69%)), the purpose of the study (76% (95% CI 27% to 100%)), voluntariness (39% (95% CI 2% to 100%)), how long the research would last (61% (95% CI 16% to 97%)), benefits (57% (95% CI 7% to 98%)) and confidentiality (44% (95% CI 10% to 82%)). Although the majority of participants appeared to want information for most of these themes, some participants did not and the level of detail that participants wanted was not explored comprehensively.

Discussion

Of the 14 papers that met inclusion criteria, five looked broadly at what information research participants wanted to know. These studies focused on the category of information required rather than how much detail participants wanted. All 14 studies had substantial limitations to generalisability when applied to the wider research population because, for example, they focused on specific subsections of the population, for example, six studies included only cancer patients23 24 26 28 30 31 and only one study conducted in the UK.30 A number of studies included only women21 26 28 30 and participants that were mostly Caucasian23 26 and well educated.23–25

In the absence of empirical evidence to suggest what information potential research participants want, the NRES have based their guidance on expert opinion. It does, however, mean that current information provision for research may not adequately address the informational needs of the general population or ‘hard to reach’ groups such as socially deprived or African–American and minority ethnic groups. While the NRES recognise that one size does not fit all and that low-risk studies with little or no intervention may need shorter information sheets, there is little empirical evidence to identify what level of information provision should be made.32 A potential difficulty in conducting research to determine what should be included in a PIS is that an individual's information preferences may change as they move from being a potential to actual participant.35 36

Responding to individuals' information needs may prove challenging, but the provision of high-quality appropriate information in a timely manner is crucial to the consent process. Electronic information provision may be one way to address different information needs. Recent research by Antoniou et al37 that allowed participants to access three increasingly detailed levels of information electronically found that the basic level of information was accessed by 70%–82% of participants, but only 9%–18% accessed the level of information currently recommended in NRES guidance and only 3%–12% accessed all three levels of information. Interestingly, 20% (93/552) participants that said they wanted more information even though fewer than this (3%–12%) read all the information available to them.

The study by Antoniou et al37 is an important first step in determining what information potential research participants really want to know when they agree to take part in a study. Further research is required to assess the feasibility and acceptability of unfolding electronic information sheets.

Limitations

Ideally, differences in informational requirements for subgroups of the population would have been explored but the small numbers of studies identified and limited data extracted from papers meant this was not feasible.

Conclusions

There is limited empirical evidence as to what information potential participants want to know at the time they are deciding whether or not to participate in research. Real-time studies need to be conducted to explore what information potential participants access when given a choice. This will enable us to determine exactly what information research participants want to know and could, in addition to other sources such as expert opinion, help tailor PIS towards specific population subgroups and enable appropriate high-quality information to be provided to meet individual needs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Kirkby HM, Calvert M, Draper H, et al. What potential research participants want to know about research: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000509. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000509

Contributors: HMK, MC, SW and HD conceived and designed the research. HMK and TK collected, validated and extracted the data. All authors made substantial contribution to the analysis and interpretation of the data. HMK drafted the manuscript and SW, HD, MC and TK revised it.

Funding: The study was funded by the Medical Research Council Midland Hub for Trials Methodology Research (Medical Research Council Grant ID G0800808). The study sponsor had no role in study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the article for publication. HMK and TK are PhD students funded by Medical Research Council Midland Hub for Trials Research Methodology and MC is Education Lead for the Medical Research Council Midland Hub for Trials Research Methodology.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that (1) HMK, MC, HD, TK and SW have support from the University of Birmingham for the submitted work; (2) HMK, MC, HD, TK and SW have no relationships with any companies that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work and (4) HMK, MC, HD, TK and SW have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work. HD is an author of one of the papers included discussion.37 SW was also acknowledged in this paper for comments on an early draft.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All authors had full access to all the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Technical appendix and data set available from the corresponding author at hmk592@bham.ac.uk. Referenced Manager (Version 12) was used to analyse data. Stats Direct was used to calculate pooled proportions with random effects.

References

- 1.The World Medical Association The World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/pmc/articles/PMC1816102/pdf/brmedj02559-0071.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.General Medical Council Seeking Patients' Consent: The Ethical Considerations. 1998. http://www.opengrey.eu/item/display/10068/387679 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, et al. Quality of informed consent: a new measure of understanding among research subjects. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:139–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHS East of England NHS Values. https://www.eoe.nhs.uk/nhs_constitution/values.php (accessed 27 Sep 2010).

- 5.NHS East of England Principles That Guide the NHS. http://www.eoe.nhs.uk/nhs_constitution/principles.php (accessed 27 Sep 2010).

- 6.Manson N. Consent and informed consent. In: Ashcroft R, Dawson A, Draper H, et al., eds. Principles of Health Care Ethics. 2nd edn Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2007:298–303 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hewlett S. Consent to clinical research–adequately voluntary or substantially influenced? J Med Ethics 1996;22:232–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Idanpaan-Heikkila JE. WHO guidelines for good clinical practice (GCP) for trials on pharmaceutical products: responsibilities of the investigator. Ann Med 1994;26:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyal L, Tobias J. Informed Consent in Medical Research. 1st edn London: BMJ Books, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Research Ethics Service Information Sheets and Consent Forms Guidance for Researchers and Reviewers. 2009. http://www.noc.nhs.uk/research/researchers/documents/npsa-guidance.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wager E, Tooley PJ, Emanuel MB, et al. How to do it. Get patients' consent to enter clinical trials. BMJ 1995;311:734–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) for Trials on Pharmaceutical Products. 1995. http://www.nus.edu.sg/irb/Articles/WHO%20GCP%201995.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Cancer Institute, US National Institutes of Health A Guide to Understanding Informed Consent. http://www.cancer gov/clinicaltrials/conducting/informed-consent-guide/allpages (accessed 5 Jun 2009).

- 14.Davis TC, Holcombe RF, Berkel HJ, et al. Informed consent for clinical trials: a comparative study of standard versus simplified forms. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998;90:668–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortun P, West J, Chalkley L, et al. Recall of informed consent information by healthy volunteers in clinical trials. QJM 2008;101:625–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grossman SA, Piantadosi S, Covahey C. Are informed consent forms that describe clinical oncology research protocols readable by most patients and their families? J Clin Oncol 1994;12:2211–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Priestley K, Campbell C, Valentine C, et al. Are patient consent forms for research protocols easy to read? BMJ 1992;305:1263–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynoe N, Hoeyer K. Quantitative aspects of informed consent: considering the dose response curve when estimating quantity of information. J Med Ethics 2005;31:736–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharpe N. Clinical trials and the real world: selection bias and generalisability of trial results. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2002;16:75–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walkup J, Bock E. What do prospective research participants want to know? What do they assume they know already? J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2009;4:59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bento SF, Hardy E, Osis MJ. Process for obtaining informed consent: women's opinions. Dev World Bioeth 2008;8:197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray SW, Hlubocky FJ, Ratain MJ, et al. Attitudes toward research participation and investigator conflicts of interest among advanced cancer patients participating in early phase clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3488–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez CV, Santor D, Weijer C, et al. The return of research results to participants: pilot questionnaire of adolescents and parents of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:441–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hampson LA, Agrawal M, Joffe S, et al. Patients' views on financial conflicts of interest in cancer research trials. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2330–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinfurt KP, Friedman JY, Allsbrook JS, et al. Views of potential research participants on financial conflicts of interest: barriers and opportunities for effective disclosure. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:901–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Partridge AH, Wong JS, Knudsen K, et al. Offering participants results of a clinical trial: sharing results of a negative study. Lancet 2005;365:963–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SY, Millard RW, Nisbet P, et al. Potential research participants' views regarding researcher and institutional financial conflicts of interest. J Med Ethics 2004;30:73–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Partridge AH, Burstein HJ, Gelman RS, et al. Do patients participating in clinical trials want to know study results? J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:491–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casarett D, Karlawish J, Sankar P, et al. Obtaining informed consent for clinical pain research: patients' concerns and information needs. Pain 2001;92:71–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maslin A. A survey of the opinions on ‘informed consent’ of women currently involved in clinical trials within a breast unit. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 1994;3:153–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sand K, Loge JH, Berger O, et al. Lung cancer patients' perceptions of informed consent documents. Patient Educ Couns 2008;73:313–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edgman-Levitan S, Cleary P. What information do consumers want and need? Health Aff (Millwood) 1996;15:42–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grady C, Horstmann E, Sussman JS, et al. The limits of disclosure: what research subjects want to know about investigator financial interests. J Law Med Ethics 2000;34:592–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutchinson A, Rubinfeld AR. Financial disclosure and clinical research: what is important to participants? Med J Aust 2008;189:207–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wyke S, Entwistle V, France E, et al. Information for choice: what people need, prefer and use. 2011. Report number 08/1710/153. http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_ES_08-1710-153_V01.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manson NC. Why do patients want information if not to take part in decision making? J Med Ethics 2010;36:834–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antoniou E, Draper H, Reed K, et al. An empirical study on the preferred size of the participant information sheet in research. J Med Ethics 2011;37:557–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.