Abstract

Objectives

The influence of family structure on the risk of going on disability pension (DP) was investigated among young women by analysing a short-term and long-term effect, controlling for potential confounding and the ‘healthy mother effect’.

Design and participants

This dynamic cohort study comprised all women born in Sweden between 1960 and 1979 (1.2 million), who were 20–43 years of age during follow-up. Their annual data were retrieved from national registers for the years 1993–2003. For this period, data on family structure and potential confounders were related to the incidence of DP the year after the exposure assessment. Using a modified version of the COX proportional hazard regression, we took into account changes in the study variables of individuals over the years. In addition, a 5-year follow-up was used.

Results

Cohabiting working women with children showed a decreased risk of DP in a 1-year perspective compared with cohabiting working women with no children, while the opposite was indicated in the 5-year follow-up. Lone working women with children had an increased risk of DP in both the short-term and long-term perspective. The risk of DP tended to increase with the number of children for both cohabiting and lone working women in the 5-year follow-up.

Conclusions

The study suggests that parenthood contributes to increasing the risk of going on DP among young women, which should be valuable knowledge to employers and other policy makers. It remains to be analysed to what extent the high numbers of young women exiting from working life may be counteracted by (1) extended gender equality, (2) fewer work hours among fathers and mothers of young children and (3) by financial support to lone women with children.

Article summary

Article focus

Explanations of the increasing rate of DP in young women in European countries.

High demands linked to family and work situation was expected to be a contributing factor.

Key messages

Parenthood contributed to an increased risk of going on DP among young women. Lone working women with children had an increased risk of DP in both a 1- and 5-year perspective.

Cohabiting working women with children had a lower risk of DP than other cohabiting women in a 1-year perspective, while the opposite was shown in a 5-year follow-up.

The number of children among working women tended to increase the risk of DP 5 years later.

Strengths and limitations of this study

High representativity and statistical precision due to complete coverage of the study group.

The possibility to utilise different time spans of follow-up, a 1-year follow-up focusing the family situation just before going on DP and a longer follow-up showing the association between family structure and risk of DP 5 years later.

The possibility to take into account the changes of family and work situation over time and to adjust for the time-dependent changes of the confounding factors considered.

Lack of information on the diagnoses of DP.

Lack of information on full time or part time work.

The generalisability is restricted to countries with a welfare system similar to that of Sweden, although the knowledge could also be a pointer for other countries developing or changing their welfare system. A similar study based on men is warranted.

Introduction

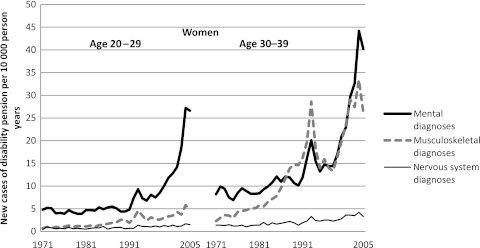

The exiting from working life due to reduced work capacity that has been occurring in Sweden and other OECD countries has entailed a heavy socioeconomic burden.1–3 In many countries, a shift in the gender structure of disability pensioners has occurred. The rates of disability pension (DP) tend to increase more (or fall less) in women, implying that women increase their share of new beneficiaries.3 A marked increase in the number of young individuals on DP based on psychiatric diagnoses has been observed, which has been most pronounced among young women.3 4 This trend has been particularly pronounced in Sweden and was an incentive for the present study focusing on young women (figure 1). The long-term development has not been linear because of changes in the labour market along with changes in the criteria for being granted a DP. Since 2004, the numbers of new DPs have declined for the population as a whole, but the downward trend does not apply to individuals below 30 years of age, according to the Swedish Social Insurance Agency.5 Also, in other Nordic countries, more and more young women have been granted a DP.6–8

Figure 1.

New cases of disability pension among women 20–29 and 30–39 years of age due to mental diagnoses (ICD-10: F00-F99), musculoskeletal diagnoses (ICD-10: M00-M99) and diagnoses of the nervous system (ICD-10: G00-G99). Sweden 1971–2005. Data source: the Swedish Social Insurance Agency.4 (Differences in ICD coding during the time period were harmonised.)

The time trends may to some extent be related to health effects among women combining a demanding work and a family life with children. Different measures have been used to study the so-called ‘double burden’ hypothesis: multiple roles, paid and unpaid work, work-to-family and family-to-work conflicts (spillover). The outcome measures as well as methodology have varied extensively.9–13 Many, but not all studies14 15 have supported the hypothesis.

With respect to DP, studies have reported results on marital status and prevalence of children in relation to risk of DP,16 often based on individuals initially on long-term sick leave17–20 and without a simultaneous consideration of work status. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study analysing the effect of family structure and work on DP, based on a representative group of young women.

Previously, we have analysed self-reported health21 22 and sickness absence23 among young women with the purposes of testing the hypothesis that their work- and career-related demands along with the demands of their family life overextended their personal resources and thus contributed to impaired health and well-being. The first two studies were cross-sectional and based on face-to-face interviews. They showed that women with children more often than others reported poor health. The associations were most pronounced among full time workers21 but did also apply to students and job seekers.22 The third study with sickness absence as a measure of ill health was based on registry data with a prospective approach. The main finding was that the risk of sickness absence was higher in working mothers compared with those without children.23 The present study is an extension of these studies, and the main objective has been to explore if the health effects previously observed could develop into illness entailing reduced work capacity and DP. Registry data were studied prospectively, and we analysed short-term and long-term effects controlling for potential confounding factors and the possibility of a ‘healthy mother effect’. The short-term follow-up gives a characterisation of young women just before they are granted a DP, while the long-term follow-up shows if family status can predict the risk of DP 5 years later.

Study population and methods

The study base comprised all women born in Sweden between 1960 and 1979, who had reached the age of 20 at baseline, which occurred between 1993 and 2003. The dynamic cohort consisted of 1 218 094 women who were between 20 and 43 years old during the follow-up period. Data were retrieved from central registers integrated in the Longitudinal Database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA).

Outcome

DP could either be full time or part time. Participants were recorded as being on DP the (first) year it was granted to them. In most cases, the women who went on DPs during the study period were issued permanent DPs. The diminished health and work capacity that is grounds for a DP in Sweden is assessed through different types of systematic medical examinations that have been approved of through Swedish social security legislation.

Exposure

Family structure was based on partner status and whether there were any children in the home who were 18 years old or younger. Cohabitation meant either married or cohabiting with children in common. Thus, if they were cohabiting without children in common, they were classified as lone. The effect of this coding should be conservative (working against the hypothesis). Four categories (cohabiting with children, cohabiting without children, lone with children and lone without children) were used. In a separate analysis, we also considered the number of children aged 18 years or younger (no children, one child, two children and three or more children).

Potential confounders

The following potential confounders were considered:

Employment was broken down into employed (including self-employed) according to one's income tax declaration (showing a registered employer) and not employed, indicated by not having returned a tax declaration with a registered employer. We used the term ‘not employed’ instead of ‘unemployed’ to separate the category from the variable below: days of unemployment part of the year (see below). To reduce potential effects from parental leave, the women were classified as employed for the year of a birth if they were recorded as employed the year before as well as the year after the delivery. The analyses were stratified according to employment status because not all the potential confounders were relevant for women without employment and because of inconsistent measurements of sickness absence.

Days of unemployment was assessed among women who had been employed sometime in the same year in which they became unemployed. The variable measured the number of days the individual had received unemployment benefits, 0 (reference), 1–15, 16–30, 31–60 and more than 60 days.

Sector of employment was also restricted to women classified as employed. It was divided into four groupings: national-level public sector (reference), local- and county-level public sector, private sector and ‘other’.

Country of birth originally included 37 different countries that were collapsed into 19 (table 1) and subsequently into three more general categories: Sweden (reference), Nordic countries other than Sweden and countries outside the Nordic region.

Residential area was separated according to population density: metropolitan areas, city areas, rural areas and sparsely populated areas (reference).

Table 1.

Demographic and socioeconomic factors related to disability pension (DP) in a 1-year follow-up during 1993–2003 among women in Sweden aged 20–43 years and born between 1960 and 1979

| Person-years | Crude rate* | Crude relative rate | Exposed cases | HR (95% CI)† | |

| Total | 10 278 639 | 39 | 39 605 | ||

| Ages during follow-up (years) | |||||

| 20–25 | 2 909 604 | 15 | 1.00 | 4345 | 1.00 |

| 26–30 | 2 964 268 | 26 | 1.75 | 7755 | 1.66 (1.60 to 1.72) |

| 31–35 | 2 814 482 | 47 | 3.14 | 13 218 | 2.92 (2.82 to 3.02) |

| 36+ | 1 590 285 | 90 | 6.02 | 14 287 | 4.54 (4.38 to 4.71) |

| Residential area | |||||

| Sparsely populated areas | 497 386 | 44 | 1.00 | 2166 | 1.00 |

| Rural areas | 507 730 | 54 | 1.25 | 2755 | 1.28 (1.21 to 1.35) |

| City areas | 5 159 644 | 41 | 0.94 | 21 061 | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.01) |

| Metropolitan areas | 4 111 669 | 33 | 0.76 | 13 621 | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.82) |

| Country of birth | |||||

| Sweden | 8 807 028 | 37 | 1.00 | 32 678 | 1.00 |

| Denmark, Finland, Norway, Iceland | 268 139 | 53 | 1.43 | 1425 | 1.20 (1.13 to 1.26) |

| UK and Ireland | 18 296 | 21 | 0.56 | 38 | 0.49 (0.36 to 0.68) |

| Poland | 62 449 | 47 | 1.26 | 293 | 1.14 (1.02 to 1.28) |

| Eastern Europe including Romania, Hungary, former DDR and USSR | 76 647 | 30 | 0.81 | 229 | 0.71 (0.62 to 0.80) |

| Bosnia–Hercegovina | 79 481 | 35 | 0.94 | 276 | 0.83 (0.74 to 0.94) |

| Former Yugoslavia excluding Bosnia–Hercegovina | 104 404 | 76 | 2.05 | 794 | 1.72 (1.60 to 1.84) |

| Greece | 11 761 | 121 | 3.25 | 142 | 2.72 (2.31 to 3.21) |

| Western Europe including Germany | 48 946 | 25 | 0.67 | 121 | 0.60 (0.50 to 0.71) |

| Iraq | 67 727 | 42 | 1.13 | 283 | 0.98 (0.87 to 1.10) |

| Lebanon, Syria and Turkey | 143 657 | 84 | 2.26 | 1204 | 2.24 (2.12 to 2.38) |

| South Central Asia including Iran | 140 861 | 53 | 1.43 | 746 | 1.34 (1.25 to 1.44) |

| Ethiopia and Somalia | 57 713 | 25 | 0.69 | 147 | 0.69 (0.59 to 0.81) |

| Africa excluding Ethiopia and Somalia | 61 247 | 46 | 1.25 | 283 | 1.12 (1.00 to 1.26) |

| East Asia including Thailand and Vietnam | 144 465 | 23 | 0.61 | 327 | 0.59 (0.53 to 0.65) |

| USA | 25 521 | 15 | 0.41 | 39 | 0.37 (0.27 to 0.50) |

| Chile | 49 665 | 48 | 1.29 | 237 | 1.27 (1.12 to 1.44) |

| South America excluding Chile | 40 229 | 32 | 0.87 | 130 | 0.84 (0.71 to 1.00) |

| Other countries | 70 403 | 30 | 0.82 | 213 | 0.75 (0.66 to 0.86) |

| Education | |||||

| High, more than 12 years | 3 208 713 | 17 | 1.00 | 5313 | 1.00 |

| Medium, 10–12 years | 5 674 755 | 40 | 2.40 | 22 577 | 2.72 (2.64 to 2.80) |

| Low, 9 years or less | 1 369 063 | 83 | 5.04 | 11 418 | 5.97 (5.78 to 6.17) |

| Employment | |||||

| Employed | 8 724 849 | 23 | 1.00 | 19 645 | 1.00 |

| Not employed | 1 553 790 | 128 | 5.71 | 19 960 | 6.76 (6.63 to 6.90) |

| Employment sector | |||||

| National public sector | 672 544 | 30 | 1.00 | 2042 | 1.00 |

| Local and county public sector | 3 417 883 | 25 | 0.83 | 8649 | 0.83 (0.79 to 0.88) |

| Private sector | 4 082 880 | 18 | 0.60 | 7435 | 0.66 (0.63 to 0.70) |

| Other sector | 517 698 | 29 | 0.95 | 1498 | 1.06 (0.99 to 1.13) |

| Days of unemployment (days) | |||||

| 0 | 7 570 643 | 42 | 1.00 | 31 486 | 1.00 |

| 1–15 | 273 581 | 41 | 0.98 | 1114 | 1.25 (1.18 to 1.33) |

| 16–30 | 238 987 | 31 | 0.74 | 738 | 1.03 (0.95 to 1.11) |

| 31–60 | 425 404 | 28 | 0.68 | 1206 | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.01) |

| >60 | 1 770 024 | 29 | 0.69 | 5061 | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.98) |

| Income | |||||

| High, above 3rd quartile | 2 600 723 | 34 | 1.00 | 8721 | 1.00 |

| Medium, 1st–3rd quartile | 4 937 461 | 41 | 1.21 | 20 095 | 1.59 (1.55 to 1.63) |

| Low, below 1st quartile | 2 554 492 | 41 | 1.23 | 10 559 | 2.32 (2.25 to 2.39) |

| Partner status | |||||

| Cohabiting | 4 750 441 | 36 | 1.00 | 17 304 | 1.00 |

| Lone | 5 528 198 | 40 | 1.11 | 22 301 | 1.82 (1.79 to 1.86) |

| Children | |||||

| Without (no) children | 4 886 709 | 32 | 1.00 | 15 464 | 1.00 |

| With children | 5 391 930 | 45 | 1.41 | 24 141 | 0.74 (0.72 to 0.76) |

| Number of children | |||||

| No children | 4 886 709 | 33 | 1.00 | 15 464 | 1.00 |

| One child | 1 769 317 | 38 | 1.16 | 6463 | 0.76 (0.74 to 0.79) |

| Two children | 2 504 169 | 42 | 1.30 | 10 573 | 0.66 (0.65 to 0.68) |

| Three or more children | 1 118 444 | 64 | 1.95 | 7105 | 0.88 (0.85 to 0.91) |

Number of new DPs per 10 000 person-years.

Adjusted for age.

Other potential confounders were education, divided into 9 years or less, 10–12 years and more than 12 years (reference), and annual income was classified, with cut-off points at the first and third quartiles, into low, medium and high income (reference). In 1998, the values at the two cut-off points were approximately €9200 and €14 200, respectively.

Statistical methods

The analytical approach of the present study was to account for the way in which individuals' exposure variables and potential confounders changed over time. The analyses were based on the SAS MPHREG macro developed at the Channing Laboratory.24 The programme has been used in other studies23 25 26 and the current application is analogous to the proportional hazard regression with time-dependent repeated measurements of time-dependent variables with the counting process style of input. The importance of methodologies taking changes over time into consideration in epidemiological studies has been emphasised.27 The difference from a traditional Cox proportional hazard regression was that the calculus was not based on the individuals' exposure at start of follow-up. Instead, an individual data record was created for each year in which the participant was at risk of receiving a DP, which allowed the individuals to change risk category status on an annual basis. With this method, all of an individual's changes regarding, for example, family structure or level of education were accounted for across time. The risk categories of a certain year were linked to DP/no DP in a subsequent year. The HR for the total follow-up period was estimated by the pooled HR across the years with a 95% CI. A joint control for age and calendar year was built into the programme.

Two time perspectives were used, a 1-year follow-up analysing the exposure situation just before being granted a DP and a 5-year follow-up analysing the predictive value of the exposure with a longer time of action. One-year follow-up: the risk categorisation was started in 1993 or the year of entry into the cohort, provided that the woman had reached the age of 20. Follow-up was discontinued at the year of DP, emigration, death or end of 2003, whichever came first. Women with a DP at baseline were excluded.

Five-year follow-up: family structure was analysed in the 5-year follow-up, using a similar methodology as in the 1-year follow-up. For each year for which a 5-year follow-up was possible (1993–1998), individual's exposure values were assessed and linked to their case status (DP/no DP) 5 years later. Individuals who received a DP or who emigrated or died before the end of a 5-year period were deleted and also excluded from further follow-up.

In an additional analysis, the women were required to be ‘healthy’ at baseline in order to reduce the possibility of selection bias (ie, ill health influencing exposure). This was done by restricting the study base to women without a registered sickness absence during the 3-year period preceding the year of exposure classification. The restriction was mainly meant to reduce the ‘healthy mother effect’.9 Sickness absence (with sickness benefits) corresponded to a medically certified sickness absence exceeding 14 days of sick leave. Sick leaves of fewer than 14 days were not considered.

Results

Exploration of potential confounders

From 1993 to 2003, 39 605 women aged 20 to 43 years were granted a DP, corresponding to a rate of 39 per 104 person-years, and 4345 DPs were granted to 20–25-year-old women. The rate increased with increasing age (table 1).

DP was most common in rural areas and least common in metropolitan areas. Country of birth showed a considerable variation, with the highest rates for those born in Greece, Lebanon–Syria–Turkey and the former Yugoslavia. The lowest rates were found for women born in the USA, the UK/Ireland, East Asia including Thailand and Vietnam, and Western Europe including Germany (table 1).

Women with low education were found to have an incidence of DP that was five times higher than for those with high education, and the same increase was found when comparing those who were not employed with those who were employed. Those employed in the national-level public sector had the highest incidence of DP, while the lowest rate was found for women in private employment. Number of days of unemployment tended to show an inverse relation to the risk of being granted a DP the following year. When it came to income, the rates were observed to increase as income level decreased (table 1).

The results caused us to keep all the variables as potential confounders in the multivariate analyses of family structure.

Family structure and disability pension

There was no remarkable difference between the crude rates for cohabiting and lone women, but the age-adjusted HR showed an 80% increase in risk for the lone women (table 1). Women with children had a somewhat higher crude rate of DP, but the age-adjusted results showed the opposite, a decreased HR compared with women without children. The crude relative rates increased by number of children, but controlling for age-decreased HRs were seen for one or more children, with the lowest HR for two children (table 1).

In the 1-year perspective (table 2), the risk of DP among cohabiting women with children was lower than that of the reference group (cohabiting without children), regardless of their working status. A similar result emerged for the two types of models (adjusting for age only and the full multivariate model). Overall, lone women showed higher HRs than cohabiting women, and among employed lone women, the HR was highest for those who had children. On the other hand, among lone women with no employment, the HR was highest for those with no children.

Table 2.

Multivariate analyses relating family structure to disability pension in a 1-year and 5-year follow-up during 1993–2003 among employed and not employed young women

| Employed |

Not employed |

|||

| Exposed cases | HR (95% CI) | Exposed cases | HR (95% CI) | |

| One-year follow-up | ||||

| Family structure* | ||||

| Total | 19 645 | 19 960 | ||

| Cohabiting + no children | 785 | 1.00 | 654 | 1.00 |

| Cohabiting + children | 9320 | 0.80 (0.74 to 0.86) | 6545 | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.96) |

| Lone + no children | 5853 | 1.08 (1.00 to 1.17) | 8172 | 2.05 (1.89 to 2.22) |

| Lone + children | 3687 | 1.35 (1.25 to 1.46) | 4589 | 1.64 (1.51 to 1.78) |

| Family structure† | ||||

| Total | 19 539 | 19 742 | ||

| Cohabiting + no children | 780 | 1.00 | 648 | 1.00 |

| Cohabiting + children | 9268 | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.78) | 6460 | 0.63 (0.59 to 0.69) |

| Lone + no children | 5835 | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.16) | 8099 | 1.35 (1.24 to 1.46) |

| Lone + children | 3656 | 1.23 (1.14 to 1.33) | 4535 | 0.99 (0.91 to 1.08) |

| Five-year follow-up | ||||

| Family structure* | ||||

| Total | 20 170 | 9598 | ||

| Cohabiting + no children | 616 | 1.00 | 241 | 1.00 |

| Cohabiting + children | 9893 | 1.31 (1.21 to 1.42) | 3954 | 1.39 (1.22 to 1.58) |

| Lone + no children | 5945 | 1.10 (1.01 to 1.19) | 3070 | 1.89 (1.66 to 2.16) |

| Lone + children | 3716 | 2.35 (2.16 to 2.57) | 2333 | 2.45 (2.15 to 2.80) |

| Family structure† | ||||

| Total | 20 057 | 9598 | ||

| Cohabiting + no children | 615 | 1.00 | 241 | 1.00 |

| Cohabiting + children | 9804 | 1.13 (1.04 to 1.23) | 3954 | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.24) |

| Lone + no children | 5938 | 1.07 (0.98 to 1.16) | 3070 | 1.44 (1.26 to 1.65) |

| Lone + children | 3700 | 1.69 (1.55 to 1.85) | 2333 | 1.62 (1.41 to 1.85) |

| 5-year follow-up ‘healthy’ at start of follow-up | ||||

| Family structure† | ||||

| Total | 6705 | 3871 | ||

| Cohabiting + no children | 215 | 1.00 | 117 | 1.00 |

| Cohabiting + children | 2778 | 1.24 (1.08 to 1.43) | 1447 | 1.18 (0.97 to 1.42) |

| Lone + no children | 2618 | 1.23 (1.07 to 1.42) | 1467 | 1.83 (1.51 to 2.22) |

| Lone + children | 1094 | 1.91 (1.64 to 2.22) | 840 | 1.94 (1.59 to 2.36) |

Adjusted for age.

The model for employed included age, residential area, country of birth, education, income, employment sector and days of unemployment. The model for not employed included age, residential area, country of birth and education.

In the 5-year follow-up (table 2), the pattern changed. Among both lone and cohabiting women, the HRs of receiving a DP tended to increase for women with children. This tendency was seen among both employed and not employed women. The pattern was similar for the two types of models, but the estimates were lower in the full multivariate models. The HRs of the full model were strengthened after controlling for health at the start of follow-up, which implied a restriction of the study group to those who had not had a medically certified sickness absence within the 3 years prior to the assessment of family structure.

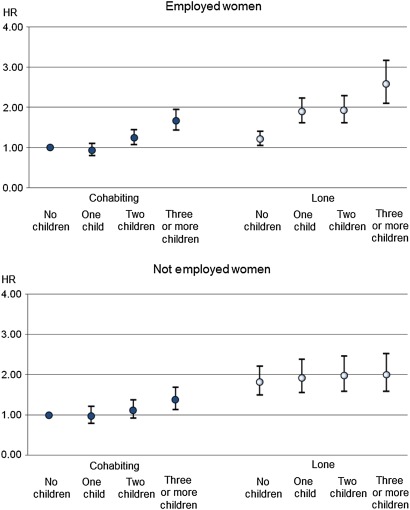

To further explore the validity of the effect of living with children in the 5-year follow-up, we added an analysis of the number of children based on the full model controlling for health at baseline (figure 2). The results suggested that the risk of DP increased with number of children for both lone and cohabiting working women, especially among lone working women. Among women without an employment, there was only a weak indication in the same direction among cohabiting women.

Figure 2.

HRs of DP according to family structure among employed and not employed young women: a 5-year follow-up based on women with no sickness absence during the 3 years before exposure assessment and with control for potential confounders.

Discussion

The relations between family structure and DP were inconsistent and varied according to employment status and the time of follow-up. Close in time to the outcome, cohabiting working women with children had the lowest risk of receiving a DP, while lone working women with children had the highest risk. The result was marginally changed when controlling for confounding. In the 5-year follow-up, on the other hand, living with children contributed in a consistent way to increasing the risk of later DP among working women.

The results for cohabiting working mothers suggested that living with children was related to a beneficial health effect when judged close in time to the outcome, which may be explained by a protective effect of social integration provided by living with a partner and children, but it may also be consequence of the short time perspective. These living conditions may show a beneficial effect for the near future but not necessarily in the long run. This was supported by the results of the 5-year follow-up, where the cohabiting working mothers were at a higher risk of receiving a DP compared with those without children. A portion of the cohabiting women who divorced within the 5-year follow-up period may have experienced a difficult divorce or other setback. Those who divorced during this follow-up were thus ‘misclassified’ part of the 5-year period and their risk of DP may therefore come closer to the pattern of lone mothers (in the 1-year follow-up, they were classified as lone). Lone working mothers had the highest risk of DP both in the short and long term, which is in line with expectations. Previous studies have clearly pointed out the vulnerability of this group,28 29 which may be explained by the heavy workload and greater responsibility that is shouldered by many of these women, as well as weak financial resources.

The results suggest that the health effects observed in previous studies on this group of young women21–23 may develop into illness entailing reduced work capacity and DP, particularly among lone working mothers.

The reasons behind the relatively high risk of receiving a DP that was found among lone women who were not employed and without children are not clear, but it is plausible that it may be connected to these individuals suffering from social isolation or marginalisation that may have been the result of severe illness or handicap early in life.30–32 Analyses of the medical diagnoses related to the DP could have helped explain these findings, but, unfortunately, such information on diagnosis-specific DP was not available for use in the study.

In the 5-year follow-up, we could at baseline control for a selection bias that we have encountered in previous studies—the ‘healthy mother effect’, implying that both partner status and the prevalence of children could be influenced by preceding illness causing the DP. The restriction of the study base to ‘healthy’ women at start of a follow-up period strengthened the effect of having children in both cohabiting and lone working women. This suggests that selection bias should be considered in studies of family structure and health. In the 1-year follow-up, where the exposure was assessed very close in time to the outcome, a comparable analysis seemed less appropriate. The requirement of no sickness absence so close in time to the DP should entail a selection of specific DP diagnoses where injuries and accidents in particular would remain.

The results show the complexity of the relation between work-family structure and DP. Because of the size of the study base, there was a high degree of representativity and statistical precision. It also allowed us to evaluate the importance of different time spans between exposure and outcome. Potential confounding factors were explored, and their relation to DP was reported. This information adds to previous knowledge on predictors of DP6 33 particularly due to the high precision at hand and the availability and use of repeated measurements.

A considerable part of the social expenses due to DP should be attributed to lone working women with children. Their illness and decreased work capacity have implications not only for the mothers but probably also for the children. The increased risk of receiving a DP among lone women without children and without a job could indicate a different trajectory in that marginalisation or social isolation may contribute to their health status and work incapacity, which needs further study. In addition, future studies should address the question about the potential health effects that may affect women who change their partner status from cohabiting mothers to lone mothers. Studies similar to the present but with a focus on men are also warranted.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Floderus B, Hagman M, Aronsson G, et al. Disability pension among young women in Sweden, with special emphasis on family structure: a dynamic cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000840. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000840

Contributors: BF: contributing to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. Drafting the article. MH: main contributor to acquisition of data and analysis. GA: contributing to analysis and interpretation of data. Revising the article critically for important intellectual content. KG: contributing to analysis and interpretation of data. Revising the article critically for important intellectual content. SM: contributing to analysis and interpretation of data. Revising the article critically for important intellectual content. AW: contributing to analysis and interpretation of data. Revising the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors have approved this version (2012-04-24) of the article.

Funding: The study was supported by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research, grant number 2009-0453.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was provided by the regional research ethics committee in Stockholm (Dnr: 2010/176-31/5).

Provenance and peer review: The work was carried out at the Department of Clinical neuroscience, Division of Insurance Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: In principle, data from the Swedish national registries are available to anyone within or outside the country who can present valid research funding and ethical approval of the research. Questions can be addressed to Statistics Sweden.

References

- 1.OECD Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers—Vol. 3: Denmark, Finland, Ireland and the Netherlands. Paris: OECD, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.OECD Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers—Sweden: Will the recent reforms make it? Paris: OECD, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.OECD Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers—A Synthesis of Findings across OECD Countries. Paris: OECD, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Försäkringskassan (The Swedish Social Insurance Agency) Diagnosmönster i förändring - nybeviljade förtidspensioner, sjukersättningar och aktivitetsersättningar 1971-2005 [Changing Diagnostic Patterns – Newly Granted Disability Pensions, Sickness and Rehabilitation Allowances 1971–2005] Försäkringskassan Redovisar. Stockholm, 2007:3 (In Swedish). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Försäkringskassan (The Swedish Social Insurance Agency) Social Insurance in Figures 2008. Försäkringskassan. Stockholm, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorngaard JH, Krokstad S, Johnsen R, et al. Epidemiologisk forskning om uförepensjon i Norden [Epidemiological Research on Disability Pensions in the Nordic Countries]. Norsk Epidemiologi 2009;19:103–14 (Review in Norwegian). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorlacius S, Stefánsson SB, Olafsson S, et al. Increased incidence of disability due to mental and behavioural disorders in Iceland 1990–2007. J Ment Health 2010;19:176–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gjesdal S, Lie RT, Maeland JG. Variations in the risk of disability pension in Norway 1970-99. A gender-specific age-period-cohort analysis. Scand J Public Health 2004;32:340–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Artazcoz L, Artieda L, Borrell C, et al. Combining job and family demands and being healthy: what are the differences between men and women? Eur J Public Health 2004;14:43–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Väänänen A, Kevin MV, Ala-Mursula L, et al. The double burden of and negative spillover between paid and domestic work: associations with health among men and women. Women Health 2004;40:1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emslie C, Hunt K, Macintyre S. Gender, work-home conflict, and morbidity amongst white-collar bank employees in the United Kingdom. Int J Behav Med 2004;11:127–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewitt B, Baxter J, Western M. Family, work and health—the impact of marriage, parenthood and employment on self-reported health of Australian men and women. J Sociol 2006;42:61–78 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harkonmäki K, Rahkonen O, Martikainen P, et al. Associations of SF-36 mental health functioning and work and family related factors with intentions to retire early among employees. Occup Environ Med 2006;63:558–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mastekaasa A. Parenthood, gender and sickness absence. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1827–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voss M, Josephson M, Stark S, et al. The influence of household work and of having children on sickness absence among publicly employed women in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:564–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samuelsson A, Alexanderson K, Ropponen A, et al. Incidence of disability pension and associations with socio-demographic factors in a Swedish twin cohort. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012 Mar 20. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 22430867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gjesdal S, Bratberg E. The role of gender in long-term sickness absence and transition to permanent disability benefits. Results from a multiregister based, prospective study in Norway 1990–1995. Eur J Public Health 2002;12:180–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gjesdal S, Bratberg E. Diagnosis and duration of sickness absence as predictors for disability pension: results from a three-year, multi-register based* and prospective study. Scand J Public Health 2003;31:246–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gjesdal S, Ringdal PR, Haug K, et al. Predictors of disability pension in long-term sickness absence: results from a population-based and prospective study in Norway 1994–1999. Eur J Public Health 2004;14:398–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karlsson NE, Carstensen JM, Gjesdal S, et al. Risk factors for disability pension in a population-based cohort of men and women on long-term sick leave in Sweden. Eur J Public Health 2008;18:224–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Floderus B, Hagman M, Aronsson G, et al. Self-reported health in mothers: the impact of age, and socioeconomic conditions. Women Health 2008;47:63–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Floderus B, Hagman M, Aronsson G, et al. Work status, work hours and health in women with and without children. Occup Environ Med 2009;66:704–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Floderus B, Hagman M, Aronsson G, et al. Medically certified sickness absence with insurance benefits in women with and without children. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:85–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hertzmark E, Spiegelman D. The SAS MPHREG Macro. Boston, MA: Channing Laboratory, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Harlow BL, et al. Reproductive factors, hormonal contraception, and risk of uterine leiomyomata in African-American women: a prospective study. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:113–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boynton-Jarrett R, Rich-Edwards J, Malspeis S, et al. A prospective study of hypertension and risk of uterine leiomyomata. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:628–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willett JB, Singer JD, Martin NC. The design and analysis of longitudinal studies of development and psychopathology in context: statistical models and methodological recommendations. Dev Psychopathol 1998;10:395–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benzeval M. The self-reported health status of lone parents. Soc Sci Med 1998;46:1337–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burstrom B, Whitehead M, Clayton S, et al. Health inequalities between lone and couple mothers and policy under different welfare regimes—the example of Italy, Sweden and Britain. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:912–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gravseth HM, Bjerkedal T, Irgens LM, et al. Life course determinants for early disability pension: a follow-up of Norwegian men and women born 1967–1976. Eur J Epidemiol 2007;22:533–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Upmark M, Thundal KL. An explorative, population-based study of female disability pensioners: the role of childhood conditions and alcohol abuse/dependence. Scand J Public Health 2002;30:191–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harkonmäki K, Korkeila K, Vahtera J, et al. Childhood adversities as a predictor of disability retirement. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:479–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allebeck P, Mastekaasa A. Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Chapter 5. Risk factors for sick leave—general studies. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2004;63:49–108 Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.