Abstract

Objectives

To test the impact of a hospital pharmacist-prepared interim residential care medication administration chart (IRCMAC) on medication administration errors and use of locum medical services after discharge from hospital to residential care.

Design

Prospective pre-intervention and post-intervention study.

Setting

One major acute care hospital and one subacute aged-care hospital; 128 residential care facilities (RCF) in Victoria, Australia.

Participants

428 patients (median age 84 years, IQR 79–88) discharged to a RCF from an inpatient ward over two 12-week periods.

Intervention

Seven-day IRCMAC auto-populated with patient and medication data from the hospitals' pharmacy dispensing software, completed and signed by a hospital pharmacist and sent with the patient to the RCF.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary end points were the proportion of patients with one or more missed or significantly delayed (>50% of prescribed dose interval) medication doses, and the proportion of patients whose RCF medication chart was written by a locum doctor, in the 24 h after discharge. Secondary end points included RCF staff and general practitioners' opinions about the IRCMAC.

Results

The number of patients who experienced one or more missed or delayed doses fell from 37/202 (18.3%) to 6/226 (2.7%) (difference in percentages 15.6%, 95% CI 9.5% to 21.9%, p<0.001). The number of patients whose RCF medication chart was written by a locum doctor fell from 66/202 (32.7%) to 25/226 (11.1%) (difference in percentages 21.6%, 95% CI 13.5% to 29.7%, p<0.001). For 189/226 (83.6%) discharges, RCF staff reported that the IRCMAC improved continuity of care; 31/35 (88.6%) general practitioners said that the IRCMAC reduced the urgency for them to attend the RCF and 35/35 (100%) said that IRCMACs should be provided for all patients discharged to a RCF.

Conclusions

A hospital pharmacist-prepared IRCMAC significantly reduced medication errors and use of locum medical services after discharge from hospital to residential care.

Article summary

Article focus

Medication administration errors are common when patients are discharged from hospital to a residential care facility (RCF). In Australia, a contributing factor is the need for the patient's primary care doctor to attend the RCF at short notice to write a medication administration chart; when the doctor cannot attend, doses may be missed or delayed and a locum doctor may be called to write a medication chart.

The objective of this study was to test the impact of a hospital pharmacist-prepared residential care medication administration chart (IRCMAC) on medication administration errors and use of locum medical services after discharge from hospital.

Key messages

Provision of a hospital pharmacist-prepared IRCMAC resulted in significant reductions in missed or delayed medication doses and use of locum medical services after discharge from hospital.

RCF staff reported that the IRCMAC improved continuity of care, and primary care doctors reported that it reduced pressure on them to attend RCFs at short notice.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first study to evaluate the impact of a hospital-provided IRCMAC on medication errors or use of locum medical services. Strengths were that the two study groups were well matched in terms of demographics, ward type, number of medications and number of RCFs.

The main limitations were the use of a pre-intervention and post-intervention study design and data collection via RCF staff telephone interview. However, quantitative data on medication errors and use of locum services were validated by strongly positive feedback from RCF staff and doctors and widespread uptake and ongoing use of the IRCMAC.

Introduction

Continuity of medication management is often compromised when patients are discharged from hospitals to residential care facilities (RCF) such as ‘nursing homes’ and ‘care homes’.1–8 Missed, delayed or incorrect medication administration is common.

Patients discharged to RCFs have complex and intensive medication needs.1 An Australian study reported that patients discharged to RCFs were prescribed an average of 11 medications of which seven were new or had been modified during hospitalisation.2 The median time between arrival at the RCF and the first scheduled medication dose was 3 h and ‘when required’ (prn) medications were sometimes needed sooner.2

In a study conducted in the USA, most patients transferred to a RCF had one or more medication doses missed; on average, 3.4 medications per patient were omitted or delayed for an average of 12.5 h.5 In another US study, medication discrepancies related to transfers to and from hospitals and RCFs resulted in adverse drug events in 20% patients.7 In an analysis of medication incidents that resulted in patient harm in Canadian long-term care facilities, patient transfer was identified as a common factor.8

Australian studies report that up to 23% of patients experience delays or errors in medication administration after discharge from hospital to a RCF.2 3 9 A key reason is difficulty accessing primary care doctors (general practitioners (GPs)) at short notice to write or update RCF medication charts.2 3 10

Delays in obtaining an up-to-date medication chart can range from a few hours up to several days.2 10 11 In the absence of an up-to-date medication chart, RCF staff may withhold medications, administer them without a current medication chart or revert to pre-hospitalisation medication regimens.2 11 The clinical significance of delays or errors in medication administration depends on the clinical status of the patient, the nature of the medications involved and the length of the delay. In some cases, no adverse event occurs. However, delays in access to medications for symptom control (eg, analgesics and medications for terminal care) can adversely impact on quality of life, and delays or errors with regularly scheduled medications (eg, anti-epileptics and antibiotics) may have serious consequences.11 Unplanned hospital readmissions have been reported as a result of failure to receive prescribed medications after transfer to a RCF.11 When the patient's GP is unable to attend, a locum medical service may be called to write the RCF medication chart; however, this does not eliminate missed doses and errors, and it adds significantly to the cost of care.2

When GPs (or locums) write RCF medication charts, they often do not have access to accurate discharge medication information.2 3 9 12 Medication changes made in hospital are frequently not explained in medical discharge summaries, and discrepancies between discharge summaries and discharge prescriptions occur in up to 80% of cases.2 9 12–15

Some Australian hospitals have attempted to improve continuity of medication management by providing 5- or 7-day interim residential care medication administration charts (IRCMACs) on discharge. These charts enable medications to be safely administered upon arrival at the RCF, without the need for urgent GP or locum attendance. They enable the GP to attend the RCF and review the patient at a clinically appropriate time, a few days after discharge, rather than on the day of hospital discharge. Use of IRCMACs is not widespread, and where they have been used, there has been no evaluation of their impact on medication administration or use of locum medical services. Most Australian hospitals do not use electronic prescribing systems and, based on anecdotal experience, expecting hospital doctors to prepare handwritten interim medication charts at the point of discharge is not a reliable, safe or sustainable method for providing IRCMACs. This is because it relies on hospital doctors remembering to write the chart, it introduces risk of discrepancies between the IRCMAC and the discharge prescription(s) and it adds to hospital doctors' workload.

For this study, a novel method for preparing IRCMACs was developed. IRCMACs were generated via hospital pharmacy dispensing software during the processing of discharge prescriptions, with auto-population of the chart with patient, prescriber and medication data (name, strength and directions). This occurred after the discharge prescription had been reviewed by a pharmacist (including reconciliation with pre-admission medications and inpatient medication charts) and errors corrected. This method was chosen to avoid the need for manual transcription, minimise additional workload and ensure the IRCMAC and discharge medications were concordant. An additional novel aspect, designed to address gaps in provision of discharge medication information, was inclusion of the ‘change status’ for each medication (unchanged, new or dose changed, with date and reason for change if known to the pharmacist), a list of medications ceased (with the date and reason, if known) and time of last dose given in hospital for each medication. These details were manually added by the pharmacist.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of the hospital pharmacist-prepared IRCMAC on continuity of medication administration and use of locum medical services following discharge to RCFs.

Methods

A prospective pre-intervention and post-intervention study was undertaken at a 400-bed acute care hospital and an 80-bed subacute aged care (geriatric assessment and rehabilitation) hospital within a major metropolitan public health service in Melbourne, Australia, over two 12-week periods (January to April and September to November 2009). A detailed analysis of the baseline (pre-intervention) data has been previously published2; this paper compares post-implementation data with that baseline data. The study was approved by the Austin Health and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committees.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were discharged to a RCF following an overnight stay on an inpatient ward. Exclusion criteria were discharge under the Transition Care Programme (a hospital-managed short-term residential care programme) or returning to an RCF with no medication changes made in hospital.

During the pre-intervention (control) period, no IRCMAC was provided. The hospitals' discharge policy included provision of at least 7 days supply of all prescribed medications for patients discharged to a new RCF or new and changed medications for patients returning to a RCF, dispensed in original packaging. A photocopy of the discharge prescription(s) was provided in the bag of medications.

During the post-intervention period, a 7-day IRCMAC was prepared by a hospital pharmacist. The IRCMAC and a photocopy of the discharge prescription(s) were placed in a transparent red plastic sleeve along with instructions for using the IRCMAC. The red sleeve was placed in a clear plastic bag with the discharge medications and transported with the patient. The pharmacist telephoned the RCF prior to discharge to notify them that an IRCMAC would be provided. No other discharge procedures were changed.

Prior to implementation of the IRCMAC, stakeholders including hospital and RCF staff, GPs and regulatory, professional and accreditation organisations were consulted (appendix 1). They provided input into the design of the IRCMAC and procedures for its preparation and use. All pharmacists involved in hospital discharge management received training in IRCMAC preparation. A standard operating procedure for use of the IRCMAC at RCFs was mailed to all RCFs that accepted patients from the health service during the pre-intervention study period.

Data collection

Data collection methods have been described in detail previously.2 Briefly, a structured telephone interview was conducted with a RCF staff member responsible for managing the patient's medications using a pre-piloted questionnaire. Interviews were conducted approximately 24 h after discharge. In the post-intervention period, for logistical reasons, interviews were not conducted on weekends; therefore, interviews for Friday and Saturday discharges occurred 48–72 h after discharge. Data collected included time of arrival at the RCF, whether the RCF medication chart had been written/updated in time for the first dose of regularly scheduled medication, who wrote/updated the chart (if written) and whether any doses had been missed or delayed since the resident arrived (and if so, the medication name and length of delay). In the post-intervention period, additional questions were asked, including whether an IRCMAC was received, whether it was used to record medication administration and whether the RCF staff member felt that the IRCMAC improved the medication transfer process. Also in the post-intervention period, a second structured telephone interview was performed on day 8 post-discharge if the patient had not had their RCF medication chart written/updated at the time of the initial interview (to determine who wrote/updated the RCF medication chart and whether the IRCMAC avoided or merely delayed locum doctor attendance).

To assess GP satisfaction with the IRCMAC, a four-item questionnaire was mailed to the GPs of patients who had been provided with an IRCMAC during the last 4 weeks of the post-intervention period, along with a pre-addressed reply-paid envelope. There was no follow-up of non-responders.

Primary end points were the proportion of patients who experienced one or more missed or significantly delayed medication doses, and the proportion of patients whose RCF medication chart was written/updated by a locum doctor, in the 24 h after discharge. Missed or significantly delayed doses were defined as regularly scheduled medication dose completely omitted, regularly scheduled medication dose delayed by more than 50% of the prescribed dose interval or ‘when required’ (prn) medication delayed by any length of time if it was required by the patient.

Secondary end points were the proportion of patients for whom a ‘workaround’ was used by RCF staff to avoid a delayed or missed dose when an updated medication chart was not available and RCF staff and GP satisfaction. A ‘workaround’ was defined as any action taken by RCF staff that was not usual practice for medication administration at the RCF (eg, using a copy of a hospital inpatient medication chart or administering medications without a medication chart).

The minimum sample size required was 112 patients per group, based on a predicted reduction in the incidence of missed or delayed doses from 25% to 10% (power 80%, level of significance 0.05, two sided). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V.19.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics). The χ2 test was used to compare categorical data and Mann–Whitney U test for all other (non-parametric) data.

Results

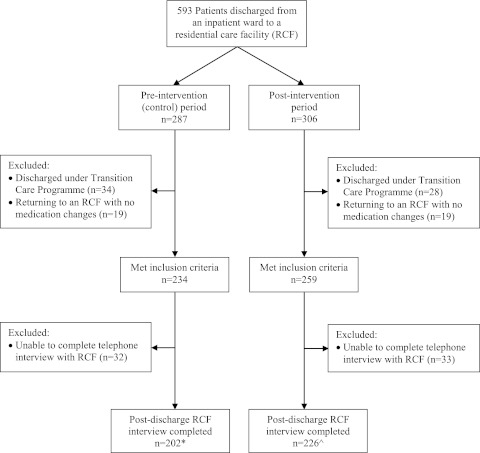

Of 593 patients discharged to a RCF, 428 met the inclusion criteria and had a post-discharge RCF staff interview completed (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram. *Discharged to 90 RCFs (median two patient transfers per RCF, IQR 1–3, range 1–9); ^discharged to 84 RCFs (median two patient transfers per RCF, IQR 1–3, range 1–14).

There were no significant differences between the pre-intervention and post-intervention groups in terms of age, gender, length of hospital stay, number of medications, level of residential care or time from discharge to first scheduled dose (table 1). The distribution of patients across RCFs was similar in the two study periods, with a median of two patients discharged to each RCF in both periods (figure 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Pre-intervention (n=202) | Post-intervention (n=226) | p Value | |

| Age (years) (median (IQR)) | 84 (79–88) | 84 (79–88) | 0.73 |

| Gender (n (%) female) | 119 (58.9) | 142 (62.8) | 0.43 |

| Length of stay in hospital (days) (median (IQR)) | 11.5 (6.0–33) | 11.0 (5.8–33) | 0.63 |

| Number of medications prescribed on discharge from hospital (median (IQR)) | |||

| Regular | 9.0 (6.5–12) | 9.0 (7.0–12) | 0.41 |

| When required (prn) | 1.0 (0–2.0) | 1.0 (0–2.0) | 0.15 |

| Total | 11.0 (7.0–13.5) | 10.0 (8.0–14) | 0.60 |

| New admission to RCF (n (%)) | 76 (37.6) | 79 (35.0) | 0.62 |

| Level of care at RCF (n (%)) | |||

| High* | 97 (48.0) | 126 (55.7) | 0.21 |

| Low† | 92 (45.5) | 89 (39.4) | |

| Other‡ | 13 (6.4) | 11 (4.9) | |

| Time between arrival at RCF and first scheduled dose due (median (IQR), minutes) | 180 (60–360) | 180 (60–330) | 0.17 |

Australian Government-approved and subsidised residential aged care place for a person who needs a high level of assistance with activities of daily living and 24-h nursing care.

Australian Government-approved and subsidised residential aged care place for a person who needs a lower level of personal and nursing care.

RCF providing non-government subsidised personal and/or nursing care (eg, Supported Residential Service).

RCF, residential care facility.

In the pre-intervention period, 75 medications for 37 (18.3%) patients had one or more doses missed or significantly delayed within 24 h of discharge from hospital. Following implementation of the IRCMAC, nine medications for six (2.7%) patients were missed or delayed (difference in percentages 15.6%, 95% CI 9.5% to 21.9%, p<0.001). Missed doses accounted for most medication administration errors: 70 (93%) pre-intervention and 9 (100%) post-intervention.

The number of RCF medication charts written or updated by a locum medical service within 24 h of discharge declined following implementation of the IRCMAC, from 66 (32.7%) to 25 (11.1%) (difference in percentages 21.6%, 95% CI 13.5% to 29.7%, p<0.001). Day 8 telephone interviews identified only one additional patient whose RCF medication chart was subsequently written/updated by a locum medical service.

One hundred and seventy-five (77.4%) patients in the post-intervention period did not have their RCF long-term medication chart written/updated by a GP or locum service in time for their first scheduled medication dose. In 147 (84%) of these cases, the RCF received and used the IRCMAC, 20 (11%) received but did not use the IRCMAC and eight (5%) did not receive the IRCMAC. The number of patients for whom a ‘workaround’ was used to avoid a missed or delayed dose fell following implementation of the IRCMAC, from 90 (44.6%) to 22 (9.7%) (p<0.001).

For 189 (83.6%) discharges, the interviewed RCF staff member reported that the IRCMAC improved continuity of medication management, and in 139 (61.5%) cases, the information about medication changes was useful. Questionnaires were sent to 84 GPs. Four were returned as the GP was no longer managing the resident's care and 35 were completed (response rate 43.8%). Thirty-one (88.6%) GPs reported that provision of an IRCMAC reduced urgency to attend the RCF after patients were discharged from the hospital, 35 (100%) said they were comfortable with a hospital-provided IRCMAC being used at the RCF for up to 7 days until they reviewed the patient, 34 (97.1%) reported that ‘Change status’ and ‘Medications ceased’ sections on the IRCMAC were helpful, and 35 (100%) agreed that provision of an IRCMAC should be standard practice for all patients discharged from hospital to a RCF. Examples of comments from RCF staff and GPs are provided in table 2, categorised by theme.

Table 2.

Examples of comments from residential care staff and general practitioners about the IRCMAC

| Theme | Comments |

| Reduction in need for urgent medical practitioner attendance |

|

| Clarity of information |

|

| Usefulness of information |

|

| Reduction in medication administration errors |

|

| Lack of familiarity with IRCMAC (RCF staff who received but did not use the IRCMAC) |

|

| Other |

|

GP, general practitioner; IRCMAC, Interim Residential Care Medication Administration Chart; RCF, residential care facility.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate a hospital-provided IRCMAC for patients discharged to residential care. It demonstrated that a 7-day IRCMAC prepared by hospital pharmacists (linked with review and processing of discharge prescriptions) improved continuity of medication administration, reduced pressure on the GP workforce and reduced the need for locum medical services to write RCF medication charts. It also led to a reduction in potentially unsafe medication administration ‘workarounds’ used by RCF staff.

Clinical outcomes were not assessed, but case reports and anecdotal evidence indicate that ‘workarounds’ and missed doses sometimes result in adverse outcomes.7 8 11 16 Of the 75 missed and delayed medications in the pre-intervention period, a moderate or high risk of adverse outcome was considered by a multidisciplinary expert panel to be likely in 49 (65.3%) cases.2

Reduced reliance on locum doctors to write medication charts after hospital discharge also has potential to improve patient safety because the locum would be unfamiliar with the patient and may not be the most appropriate person to write the long-term care medication chart (which may be used for up to 6 months). The IRCMAC enabled GPs to review their patients (and write long-term care medication charts) at a clinically appropriate time, a few days after discharge, rather than on the day of hospital discharge (when the patient should not require a clinical review).

The duration of the IRCMAC was limited to 7 days to ensure that post-discharge medical review could not be excessively delayed, while also providing flexibility for GPs in the scheduling of their visit to the RCF (during stakeholder consultation, some GPs reported that they usually attend the RCF for routine patient care activities on a set day each week). If the patient is stable and the GP's usual day of attendance is 7 days away, a 7-day chart avoids the need for the GP to make an extra visit and/or the need for locum attendance. If the patient is clinically unstable, the GP can attend sooner.

We did not assess whether there was a change in the time from hospital discharge to first GP visit. Anecdotally we noted that the chart was usually used for <7 days. While there is a potential risk that the IRMCAC may delay GP review of an unstable patient, the risk may be smaller with the IRCMAC than without the IRCMAC. This is because without the IRCMAC, a locum medical service is often called to write a long-term care medication chart on the day of discharge,2 and this chart will last for up to 6 months; therefore, the patient's GP can delay their attendance for much longer than 7 days.

Another benefit of reducing reliance on locum medical services is that it reduces healthcare costs. If the results of this study were replicated across all hospitals in Australia (based on 2001–2002 discharge data17 and the minimum Medicare Australia locum medical consultation rebate in 2010 ($A126)), savings to the Australian Government in excess of $A2.1 million annually could be realised. Avoidance of adverse medication events may lead to further cost savings. The IRCMAC could also lead to efficiency gains within the RCF and GP workforce; telephone interviews and satisfaction surveys suggested that the IRCMAC resulted in considerable (though unquantified) time savings for RCF staff and GPs. Countering these savings would be costs incurred by hospitals to deliver the IRCMAC, but in our experience, these are significantly less than the likely savings (approximately 10 Australian dollars per IRCMAC for labour and consumables, excluding software and set-up costs, in a setting in which pharmacists were already conducting admission and discharge medication reconciliation and entering discharge medication data into dispensing software; greater labour costs for IRCMAC provision would be incurred if these tasks needed to be introduced).

Although RCF medication charts are traditionally written by medical practitioners, the IRCMAC used in this study was able to be legally prepared and signed by the pharmacist because in the RCF setting, the chart was an administration record, not a prescription, and therefore did not need the signature of a medical practitioner. Preparing the IRCMAC in this way provided a number of advantages. It ensured that IRCMAC production occurred after the discharge prescription had been reviewed and reconciled by a pharmacist and errors corrected, and it enabled auto-population of the chart from the pharmacy dispensing software. This ensured a high level of concordance between the IRCMAC and the discharge prescription. An audit of a random selection of 76 IRCMACs prepared during this study revealed a medication discrepancy rate of 9/870 (1.0%).18 Although there are no studies that have assessed accuracy of handwritten IRCMACs, medication transcription error rates on handwritten inpatient orders and discharge summaries range from 12% to 56%.14 19–21

For 11% of patients, the RCF received an IRCMAC but did not use it. In some cases, this was because a doctor attended in time to write a new RCF medication chart. In other cases, it was because the RCF had a policy requiring all admissions to be reviewed/admitted by a medical practitioner or stating that all medication administration charts must be written by a medical practitioner. Sometimes RCF staff did not use the chart because they were unfamiliar with it (table 2).

In our study, the hospital supplied medications on discharge along with the IRCMAC. In settings in which the hospital does not supply discharge medications, the IRCMAC may be less effective but would still be expected to provide some benefits. It may reduce pressure on the GP workforce and use of locum medical services. And because the IRCMAC provides RCF staff with clarity as to what the intended discharge regimen is, if pre-admission medications are available at the RCF, with an IRCMAC, they can be given correctly, without delay. For new or changed medications, whether the IRCMAC would be effective will depend on how the medications are supplied—if delays in medication supply and/or delivery occur then missed doses may still occur until the medications become available, but if the medications are supplied on time (within 1–6 h of discharge), the IRCMAC could facilitate timely and accurate administration.

There were some limitations with our study methodology. Data on missed and delayed doses were obtained by telephone interview, introducing risk of under-reporting and recall bias. However, as described elsewhere,2 we piloted several methods of data collection, and telephone interview 24 h after discharge was judged to be the most reliable and practical. Any under-reporting and recall bias is likely to have been similar during the pre-intervention and post-intervention periods. While transfer-related medication administration errors may continue for several days after discharge,4 9 our methodology did not enable us to assess what proportion of errors persisted beyond 24 h after discharge. Use of a pre-intervention and post-intervention study design meant that the interviewer could not be blinded to group allocation and that factors other than the IRCMAC could have contributed to the reduction in medication administration errors and locum medical service attendances over time. However, the strongly positive feedback from GPs and RCF staff regarding the impact of the IRCMAC suggests that it was the primary cause of observed improvements and because the problems addressed by the IRCMAC have been long standing, it is unlikely that over the space of a few months, they would decline significantly without specific intervention. Furthermore, the participating hospitals have continued to provide IRCMACs since this study finished and (unsolicited) positive feedback continues to be received. Several RCFs have indicated that they are now happy to accept patients on weekends or after hours, provided they receive the IRCMAC, whereas previously they would not. A major locum medication service in the area has indicated that since the IRCMAC was introduced, they infrequently receive calls to write medication charts following hospital discharge. Data were collected from RCFs within approximately 24 h for all discharges in the pre-intervention period, but up to 48–72 h in the post-intervention period for Friday and Saturday discharges (24 h for all others). It is possible that the longer time between discharge and interview in the post-intervention period may have increased the risk of recall bias. However, Saturday discharges were rare (5/226), and it was our experience that delaying interviews for Friday discharges until Monday was advantageous because the interview was more likely to involve a RCF staff member who was present on Friday, when the patient arrived. Therefore, this minor difference in methodology was unlikely to have resulted in underestimation of error prevalence.

In conclusion, implementation of a hospital pharmacist-prepared IRCMAC led to significant improvements in continuity of medication administration and reduced reliance on locum medical services to write medication charts after discharge from hospital to RCFs. As a result of this study, hospital pharmacist-prepared IRCMACs have been implemented in several Australian hospitals, and a national IRCMAC and guidelines addressing continuity of medication management on transfer from hospital to RCF are planned. Although health systems vary between countries, problems with continuity of medication management on discharge from hospital to residential care have been reported internationally,2 5 8 so the findings of this study may be widely applicable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the following people in the conduct of the study: Clare Chiminello (North East Valley Division of General Practice), Kent Garrett (Austin Health), Stephen Cheung (Austin Health), Liam Carter (Northern Health), Marion Cincotta (Northern Health), the hospital pharmacists who assisted with implementation of the IRCMAC and RCF staff who participated in telephone interviews.

Appendix 1. Stakeholders consulted during development of the IRCMAC

Australian government and professional bodies:

Aged Care Standards & Accreditation Agency

Australian Nursing Federation

North East Valley Division of General Practice

Northern Division of General Practice

Nurses Board of Victoria

Pharmacy Board of Australia

Victorian Department of Health—Aged Care Branch

Victorian Department of Health—Ambulatory & Continuing Care Programs Branch

Victorian Department of Health—Drugs and Poisons Unit

Victorian Department of Health—Quality Use of Medicines Programme

Individual health professionals and aged care staff:

Community pharmacists (n=4)

Hospital pharmacists (n=6)

Hospital doctors (n=3)

Hospital aged care liaison nurse (n=1)

RCF staff (directors of nursing, care coordinators, division 1 & 2 registered nurses, personal care assistants) (n=34)

GPs (n=6)

Footnotes

To cite: Elliott RA, Tran T, Taylor SE, et al. Impact of a pharmacist-prepared interim residential care medication administration chart on gaps in continuity of medication management after discharge from hospital to residential care: a prospective pre- and post-intervention study (MedGap Study). BMJ Open 2012;2:e000918. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000918

Contributors: RAE, SET and PAH conceived the study and developed the methodology with input from all investigators. RAE wrote the study protocol and managed the study. TT collected the data. RAE and TT conducted the data analysis with input from SET, PAH and JLM. RAE wrote the manuscript. All investigators reviewed and contributed to the manuscript.

Funding: JO and JR Wicking Trust, which had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, data analysis or preparation of this paper.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Austin Health Human Research Ethics Committee and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Access to the study data may be provided by the authors to other researchers upon request.

References

- 1.Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:549–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott RA, Tran T, Taylor SE, et al. Gaps in continuity of medication management during the transition from hospital to residential care: an observational study (MedGap Study). Australas J Ageing. Published Online First: 16 February 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6612.2011.00586.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pierce D, Fraser G. An investigation of medication information transfer and application in aged care facilities in an Australian rural setting. Rural and Remote Health. 2009;9:1090 http://www.rrh.org.au/publishedarticles/article_print_1090.pdf (accessed 21 Dec 2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald T. For their Sake: Can We Improve the Quality and Safety of Resident Transfers from Acute Hospitals to Residential Aged Care? Australian Catholic University, 2007. http://www.acaa.com.au/files//generalpapers/for_their_sake_oct_07_final.pdf (accessed 8 Dec 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward KT, Bates-Jensen B, Eslami MS, et al. Addressing delays in medication administration for patients transferred from the hospital to the nursing home: a pilot quality improvement project. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2008;6:205–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tjia J, Bonner A, Briesacher BA, et al. Medication discrepancies upon hospital to skilled nursing facility transitions. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:630–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boockvar K, Fishman E, Kyriacou CK, et al. Adverse events due to discontinuations in drug use and dose changes in patients transferred between acute and long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:545–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada Medication incidents occurring in long-term care. ISMP Canada Safety Bulletin. Vol 10: Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada). 2010:1–3 http://www.ismp-canada.org/download/safetyBulletins/ISMPCSB2010-09-MedIncidentsLTC.pdf (accessed 8 Dec 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crotty M, Rowett D, Spurling L, et al. Does the addition of a pharmacist transition coordinator improve evidence-based medication management and health outcomes in older adults moving from the hospital to a long-term care facility? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2004;2:257–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tran T, Taylor S, Chu M, et al. Complexities of patient transfer from hospital to aged care homes: far from achieving a smooth continuum of care [abstract]. Proceedings of the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia Federal Conference. Sydney: The Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia, 2007:p63 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott RA, Taylor SE, Harvey PA, et al. Unplanned medication-related hospital readmission following transfer to a residential care facility. J Pharm Pract Res 2009;39:216–18 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians. JAMA 2007;297:831–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witherington EM, Pirzada OM, Avery AJ. Communication gaps and readmissions to hospital for patients aged 75 years and older: observational study. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:71–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callen J, McIntosh J, Li J. Accuracy of medication documentation in hospital discharge summaries: a retrospective analysis of medication transcription errors in manual and electronic discharge summaries. Int J Med Inform 2010;79:58–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson S, Ruscoe W, Chapman M, et al. General practitioner-hospital communications: a review of discharge summaries. J Qual Clin Pract 2001;21:104–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boockvar KS, Liu S, Goldstein N, et al. Prescribing discrepancies likely to cause adverse drug events after patient transfer. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:32–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karmel R, Gibson D, Lloyd J, et al. Transitions from hospital to residential aged care in Australia. Australas J Ageing 2009;28:198–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran T, Elliott RA, Taylor S, et al. Development and evaluation of an interim residential care medication administration chart prepared by hospital pharmacists. J Pharm Pract Res. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Doormaal JE, van den Bemt PMLA, Mol PGM, et al. Medication errors: the impact of prescribing and transcribing errors on preventable harm in hospitalised patients. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:22–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fahimi F, Nazari MA, Abrishami R, et al. Transcription errors observed in a Teaching hospital. Arch Iranian Med 2009;12:173–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lisby M, Nielsen LP, Mainz J. Errors in the medication process: frequency, type, and potential clinical consequences. Int J Qual Health Care 2005;17:15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.