Abstract

Introduction

Patients admitted to hospital with acute respiratory symptoms remain a diagnostic challenge for the emergency physician. The use of focused sonography may improve the initial diagnostics, as most of the diseases, commonly seen and misdiagnosed in patients with acute respiratory symptoms, can be diagnosed with sonography. The protocol describes a prospective, blinded, randomised controlled trial that aims to assess the diagnostic impact of a pragmatic implementation of focused sonography of the heart, lungs and deep veins as a diagnostic modality in acute admitted patients with respiratory symptoms.

Methods and analysis

The primary outcome of the study is the number of patients with a correct presumptive diagnosis within 4 h of admission to the emergency department. The patient is randomised to either an intervention or a control group. In the intervention group, the usual initial diagnostic work up is supplemented by focused sonographic examination of the heart, lungs and deep veins of the legs. In the control group, usual diagnostic work up is performed. The χ2 test, alternatively the Fischer exact test will be used, to establish whether there is a difference in the distribution of the total number of patients with a correct/incorrect ‘4 h’ presumptive diagnosis in the control group and in the intervention group.

Ethics and dissemination

This clinical trial is performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Regional Scientific Ethical Committee for Southern Denmark and the Danish Data Protection Agency. The results of the trial will be published according to the CONSORT statement with the extension for pragmatic trials. The results of the trial will be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal regardless of the outcome.

Trial registration number

This study is registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov, registration number NCT01486394.

Article summary

Article focus

Focused sonography of the heart, lungs and deep veins.

Initial diagnostics of acute admitted patients with respiratory symptoms.

Key messages

The results of the study may help to determine whether sonography should be included as a fully integrated part of the primary evaluation in these patients.

Strengths and limitations of this study

First randomised trial to compare the overall diagnostic performance between the conventional approach and an approach including focused sonography to evaluate and diagnose acute admitted patients with respiratory symptoms, admitted to an emergency department.

Pragmatic design with inclusion of most patients with respiratory symptoms.

Single-centre study that could affect external validity.

Study not powered to investigate morbidity or mortality.

Introduction

Patients admitted to hospital with acute respiratory symptoms remain a diagnostic challenge for the emergency physician. At the primary evaluation, the clinician has to rely on the clinical examination when initiating treatment and further diagnostic work up. Beside the history taking and clinical examination, the initial diagnostics usually consist of blood samples, an ECG and a conventional chest x-ray (CXR).

Several studies have questioned the diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination.1–7 The conventional CXR also has its drawbacks and often a supine CXR is the only possible solution in the most critically ill patients. In addition, the diagnostic accuracy of the CXR in the diagnosis of acute respiratory diseases such as pulmonary oedema, pneumonia, pleural effusion and pneumothorax has been debated.8–11

The limitations of the initial investigations of acute admitted patients with respiratory symptoms may cause a significant proportion of the patients to receive a wrong diagnosis and thereby inappropriate treatment.12 An incorrect diagnosis and initiation of an inappropriate treatment is associated with a higher mortality and an increased length of the hospital stay in elderly patients admitted with acute respiratory failure in an emergency department (ED).12 Most of the patients misdiagnosed in the ED have very common diseases, such as heart failure, pulmonary oedema, community-acquired pneumonia, pulmonary embolism and obstructive pulmonary diseases.12 A major challenge for the emergency physician is to achieve an as accurate presumptive diagnosis as possible and to differentiate between the most common causes for acute respiratory failure.

One method showing itself promising in improving the initial diagnostics is the use of focused sonography, as most of the diseases, commonly seen and misdiagnosed in patients with acute respiratory symptoms, can be diagnosed with sonography.5 11 13–22 Although the sonographic findings are normal in patients with obstructive pulmonary disease, sonography seems to be useful in ruling out many coexisting diseases in these patients.5 17 The cause of acute respiratory failure most often originate from the heart, lungs and deep veins of the legs12 23 of which all three can be directly visualised using this approach. A combination of focused sonography of the heart, lungs and deep veins would therefore, theoretically, lead to a better differentiation between many of the causes of acute respiratory failure and thus must likely increase the diagnostic accuracy.

Patients admitted and triaged to the medical section of our ED with respiratory symptoms should have a presumptive diagnosis within 4 h of admission. The current standard is that the presumptive diagnosis is based on an evaluation performed by an ED physician in combination with initial diagnostics such as blood samples, ECG and CXR. We therefore aim to investigate whether the supplemental use of focused sonography of the heart, lungs and deep veins as a standard diagnostic tool increases the proportion of acute admitted patients with respiratory symptoms that are correctly diagnosed within 4 h of admission compared with our current initial investigations (eg, blood samples, ECG, CXR and an evaluation performed by an emergency physician).

Study purpose

The main purpose of the study is to evaluate whether the use of sonographic examination of the heart, lungs and deep veins of the legs can improve the total number of patients correctly diagnosed within the first 4 h of admission, in an unselected population of patients with respiratory symptoms who are acute admitted to the medical section in an ED compared with the conventional diagnostics without focused sonography (control group) using blinded audit as the gold standard.

Trial design and methods

The study will be conducted as a blinded, prospective randomised controlled trial. The trial will use a parallel group design with a 1:1 allocation ratio. The framework chosen for the trial is a pragmatic and superiority design.

The trial aims to assess the diagnostic impact of the implementation of focused sonography of the heart, lungs and deep veins as a diagnostic modality in acute admitted patients with respiratory symptoms. The primary outcome of the study is the number of patients with a correct presumptive diagnosis within 4 h of admission to the ED. As secondary outcomes, the impact of sonography on inhospital and 30 day mortality, length of hospital stay and number of patients receiving appropriate treatment within 4 h of admission in the ED will be assessed.

The study will take place at the ED at Odense University Hospital, Denmark. In 2010, the ED had 8300 medical admissions. Due to organisational changes, this number is expected to rise significantly during the study period. All patients with respiratory symptoms as the primary complaint are admitted to the medical section of the ED. Patients suspected of having a heart disease (eg, acute myocardial infarction, pulmonary oedema, arrhythmia) are, however, admitted directly to our cardiology department.

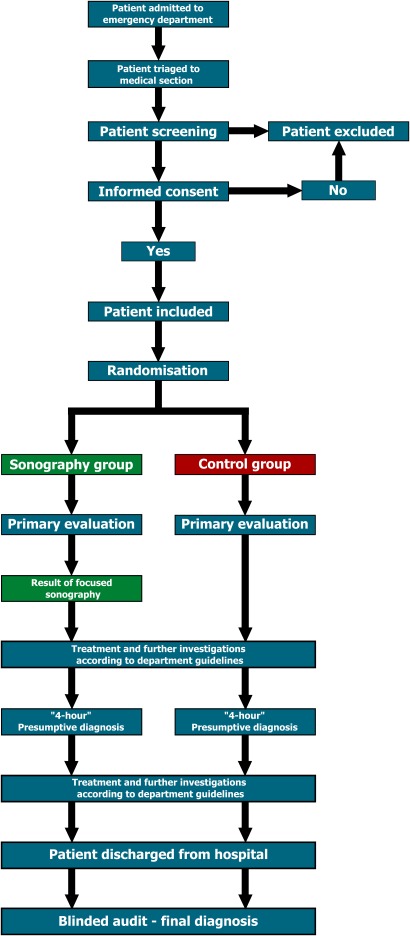

The results of the study will be reported according to the CONSORT guidelines for pragmatic trials.24 An overview of the patient flow in the clinical trial is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patient flow in the clinical trial.

Participants

We will recruit 320 acutely admitted patients with respiratory symptoms through the ED at Odense University Hospital, Denmark. Patients will only be recruited if they are triaged to the medical section of our ED. Using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the patients triaged to the medical section will be screened for participation in the study. The screening is performed by the primary investigator. Patients triaged to other sections of the ED (eg, trauma, abdominal surgery, obstetrics, gynaecology) will not be screened for participation in the project.

Immediate after screening patients receive oral and written information about the study, the information is given by the primary investigator. The written information used has been approved by the regional scientific ethical committee. If the patient is willing to participate in the study, written and oral informed consent will be obtained by the primary investigator.

Patient enrolment is carried out during all 24 h of the day.

Inclusion criteria

All five of the following must be present:

Patient is triaged to the medical section of the ED.

The sonographic examination can be performed before or within 1 h after the primary evaluation.

Patient age ≥18 years.

Informed consent is available.

-

The presence of one or more of the following symptoms or clinical findings at admission to the ED.

–Respiratory rate >20 breaths per minute.

–Saturation <95%.

–Oxygen therapy initiated.

–The patient has a principal complaint of dyspnoea.

–The patient has a principal complaint of coughing.

–The patient has a principal complaint of chest pain.

Exclusion criteria

One of the following:

The sonographic examination cannot be performed before or within 1 h after the primary evaluation.

Patient age <18 years.

Informed consent is not available.

Randomisation

By the use of a random number generator, the randomisation lists will be established before initiating the study. The unique identification number and group assignment will be printed on a label and then fixed to a folded paper card. The card will be placed in a coloured envelope. This makes it impossible to see the group that the patient is assigned to through the sealed envelope.

Once the patient has been included in the study, the randomisation will be performed. An investigator will open the randomisation envelope containing the patient's unique identification number that also decides whether the patient is randomised to the sonography group or the control group.

Blinding

In order to blind to the physicians performing the final diagnosis audit, the results of the randomisation and the results of the sonographic examinations are kept in a sealed envelope in the patient's paper journal. The physicians performing the audit have access to the patients' electronic journal. However, they are blinded to the paper journal and thereby the results of the randomisation and sonographic examinations. The emergency physicians are instructed not to record the results of the randomisation or the sonographic examinations in the electronic journal.

Interventions

The patient is randomised to either an intervention or a control group. In the intervention group, the usual initial diagnostic work up (eg, evaluation by an ED physician, blood samples, ECG and CXR) is supplemented by focused sonographic examination of the heart, lungs and deep veins of the legs. In the control group, usual diagnostic work up is performed. In both groups, the patient is clinically assessed by the ED physician leading to registration of presumptive diagnosis, treatment initiated and any supplemental diagnostics ordered. The last performed evaluation within the first 4 h is used as the final ‘4-h’ presumptive diagnosis.

Sonography group

For patients randomised to the intervention group, sonographic examination of the heart, lungs and deep veins will be performed before or within 1 h after the primary evaluation. The emergency physicians in our department do not have the competencies to perform focused sonography. Instead the sonographic examinations will be performed by a physician qualified for focused sonography (first author CBL). The results of the sonographic examinations are registered in a report sheet and delivered to the ED physician who is in charge of the patient's treatment and further investigations. Then the ED physician re-evaluates the suspected diagnosis along with treatment initiated and further diagnostics ordered. Furthermore, the ED physician grades the clinical information of the sonographic examination. The information is graded into one of the five following categories:

Inadequate information.

No new information.

No new information but presumptive diagnosis confirmed by sonography.

Added new information (but no change in treatment/further investigations).

Added decisive information (changes made in treatment/further investigations).

The diagnostic criteria for the sonographic examinations are listed in online appendix I. The sonographic examinations are performed according to the following protocols:

–Focused echocardiography: performed using the Focus Assessed Transthoracic Echocardiography protocol.25 The lung views used in the original Focus Assessed Transthoracic Echocardiography protocol are performed as a part of the lung sonography.

–Lung sonography: performed using the principles described by Lichtenstein.26

–Limited compression ultrasonography: performed according to the American College of Emergency Medicine's imaging criteria compendium.27

Beside the sonographic examination, patient treatment and other diagnostic examinations performed during the patient's hospital admission are performed according to the ED guidelines.

Control group

The treatment and further investigations of the patients in the control group are performed according to the ED guidelines.

Outcome measures

Primary

The primary outcome of the study is to establish whether the use of sonographic examination of the heart, lung and deep veins will increase the proportion of patients with a correct presumptive diagnosis within 4 h after hospital admission, using the final diagnosis obtained by audit as the gold standard. The methods used for the audit are described in online appendix II.

In our ED, the primary evaluation should have been performed and all primary diagnostic examinations (eg, blood samples, ECG, CXR) should be available within 4 h after patient admission. Due to this, we have chosen the 4 h limit as the ‘cut-off point’ at which we compare the number of patients with a correct presumptive diagnosis in the two groups.

Secondary

As a part of the secondary end points, we will compare the two groups for differences in:

–Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and diagnostic accuracy of the primary evaluation by an ED physician and the ‘4-h’ presumptive diagnosis.

–The proportion of patients with a correct presumptive diagnosis after the primary evaluation by an ED physician.

–The proportion of patients receiving an appropriate, inappropriate and no specific treatment within 4-h of admission.

–The proportion of patients where treatment with diuretics, bronchodilator therapy, steroids, antibiotics and antithrombotic medication are initiated within 4-h of admission.

–Total number and type of further investigations ordered at the primary evaluation by an ED physician (eg, thoracocenthesis, CT, echocardiography).

–Number of further investigations ordered by the ED physician that confirmed or could not confirm the suspected diagnosis.

–Time to diagnostic/therapeutic thoracocenthesis.

–30 day mortality from admission.

–Inhospital mortality.

–Length of hospital stay.

–Number of hospital-free days within 1 month after admission.

–Number of readmissions within 1 month after admission.

–Number of patients transferred to an intensive care unit.

These comparisons are exploratory by nature, and any positive findings will be interpreted conservatively.

For the intervention group, using the blinded audit as gold standard, we will determine:

–Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and diagnostic accuracy of the sonographic examinations.

–Time used to perform the sonographic examinations.

–Patient position during the sonographic examination.

–Image quality of the sonographic examinations (grading scale is described in online appendix I).

–Feasibility for the sonographic examinations (definition of feasibility is described in online appendix I).

–Clinical value of the sonographic examinations as graded by the emergency physicians performing the primary evaluation.

–Clinical value of the sonographic examinations determined by the number of presumptive diagnosis made at the primary evaluation that are changed after the result of the sonographic examinations is revealed for the emergency physician.

–Patient graded discomfort experienced during the sonographic examination (described in online appendix I).

Sample size determination

Based on the preliminary non-published results of a descriptive pilot study (n=139) using the same inclusion criteria, approximately 65% of the eligible patients will have a correct presumptive diagnosis within 4 h after admission if sonography is not used. A clinically significant improvement in the presumptive diagnosis by the use of sonography would be an absolute improvement of at least 10%. Based on the preliminary results, the sonographic examination approximately increases the proportion of patients with a correct presumptive diagnosis to 80%. If 65% of the patients in the control group achieve a correct presumptive diagnosis and 80% in the intervention (sonography) group achieve a correct diagnosis, then a power of 80% at the 5% level is obtained with a sample size of 150 patients in each group. Allowing for a 6% dropout after randomisation, it is planned to enrol 160 patients in each group, that is, a total of 320 patients.

Data analysis

Descriptive data

Descriptive statistics for both groups will be given including demographic characteristics; health characteristics; patient symptoms; measured variables in the ED; type of treatment initiated in the ED; total number and proportion of patients receiving appropriate, inappropriate and no specific treatment; other investigations ordered in the ED; need for referral for intensive care unit; time (eg, length of hospital stay, time to other imaging modality), mortality (eg, inhospital mortality, 30 day mortality), number of hospital-free days within 1 month after admission and number of readmissions within 30 days.

In the intervention group, the descriptive statistics will also include the clinical value of the sonography (as graded by the physician receiving the sonography rapport sheet), time (eg, time to sonography after primary evaluation, time to complete sonography), image quality, feasibility of the sonographic examinations, patient position while doing sonography and the patient graded experience of the sonographic examination.

Categorical data will be summarised using number and proportion of patients, while continuous data will be presented using the number of patients (n), mean, SD, median, minimum and maximum.

Primary end point

The χ2 test, alternatively the Fischer exact test will be used, to establish whether there is a difference in the distribution of the total number of patients with a correct/incorrect ‘4 h’ presumptive diagnosis in the control group and in the intervention group.

Secondary end points

To compare the intervention group with the control group, the following test will be used: for the comparison means, we will use the Student t test; for the comparison of medians, we will use the Mann–Whitney test and for the comparison of proportions, we will use the χ2 or the Fisher exact test. All tests will be performed with a two-sided significance level of 5%.

Using the audit diagnosis as the gold standard, for both groups, we will assess the diagnostic performance of the primary evaluation, the ‘4-h’ presumptive diagnosis and the sonographic examinations by calculating sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values, negative predictive values and diagnostic accuracy and their 95% CI.

We will analyse data using the intention-to-treat principle. Data analysis will be conducted using STATA Release V.11.0 (StataCorp).

Data entry and security

Measured data are initially handwritten into a case report form. The case report forms will be transferred using double data entry into a computer database. In the database, each patient has a unique identification number securing patient identity. The database is stored on a hospital computer that is password protected and only can be accessed by the primary investigator and the physician who monitor data collection. The physicians performing the blinded audit do not have access to the database until after all audits have been completed and entered into the database. The computer and case report forms are stored in locked room at the research unit. All data are stored and managed according to the laws and regulations as stated by the Danish Data Protection Agency.28

Trial organisation and monitoring

The authors of this protocol comprise the investigative team of this clinical trial. The principal investigator will perform patient screening, enrolment and sonography in the intervention group. The principal investigator manages data collection and flow, while one of the associate investigators (FR) monitors data collection, flow and integrity throughout the process.

Focused sonography carries no risk for the patient since its pain and radiation free; hence, a Data Monitoring Committee has not been appointed for the trial.

The patient allocations are concealed from the physicians performing the blinded audit (DPH, PHM and JRD). The auditors will only have access to the participant's electronic patient journal for the audit, but any information about allocation or result of the sonographic examinations is blinded for the auditors. No interim analysis or endpoint adjustments are planned.

Discussion

This trial will be the first study to compare the overall diagnostic performance between the conventional approach to evaluate and diagnose acute admitted patients with respiratory symptoms, admitted to an ED, with a new approach that combines the conventional method with focused sonography of the heart, lungs and the deep veins in the legs. The results of the study may help to determine whether sonography should be included as a fully integrated part of the primary evaluation in these patients.

Ethical considerations and dissemination

Sonography is a non-invasive pain and radiation-free diagnostic imaging modality. The sonographic examinations performed in the study do not pose an additional risk for the patients in the intervention group. Beside the sonographic examinations, treatment and other investigations performed in the intervention group are done according to department/hospital guidelines.

This clinical trial is performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Regional Scientific Ethical Committee for Southern Denmark and the Danish Data Protection Agency.29 The study was registered with http://clinicaltrials.gov, registration number NCT01486394.

Publication policy

The results of the trial will be published according to the CONSORT statement with the extension for pragmatic trials.24 The results of the trial will be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal regardless of the outcome.

Projected timetable for trial

October 2010: study approved by the Regional Scientific Ethical Committee for Southern Denmark.

November 2011: patient enrolment begins.

May 2012: patient enrolment completed.

August 2012: data entry completed.

October 2012: data analysis completed.

March 2013: article with study results submitted for publication.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Laursen CB, Sloth E, Lassen AT, et al. Focused sonographic examination of the heart, lungs and deep veins in an unselected population of acute admitted patients with respiratory symptoms: a protocol for a prospective, blinded, randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001369. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001369

Contributors: CBL conceived the idea for this clinical trial and is the primary investigator. All authors contributed to writing and reviewing the protocol, including the process of submitting the protocol for publication. CBL will perform all the sonographic examinations in the intervention group.

Funding: The study is funded partly by the Research Unit at the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, and partly by grants from: The University of Southern Denmark, Research Board at Odense University Hospital and The Højbjerg Fund.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics for The Region of Southern Denmark.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Badgett RG, Lucey CR, Mulrow CD. Can the clinical examination diagnose left-sided heart failure in adults? JAMA 1997;277:1712–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiteri MA, Cook DG, Clarke SW. Reliability of eliciting physical signs in examination of the chest. Lancet 1988;1:873–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wipf JE, Lipsky BA, Hirschmann JV, et al. Diagnosing pneumonia by physical examination: relevant or relic? Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1082–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leuppi JD, Dieterle T, Koch G, et al. Diagnostic value of lung auscultation in an emergency room setting. Swiss Med Wkly 2005;135:520–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenstein D, Mezière G. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure. The BLUE protocol. Chest 2008;134:117–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lichtenstein D, Goldstein I, Mourgeon E, et al. Comparative diagnostic performances of auscultation, chest radiography, and lung ultrasound in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology 2004;100:9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes RW, Wu KK, Hoak JC. Fallability of the clinical diagnosis of venous thrombosis. JAMA 1975;234:605–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins SP, Lindsell CJ, Storrow AB, et al. Prevalence of negative chest radiography results in the emergency department patient with decompensated heart failure. Ann Emerg Med 2006;47:13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syrjälä H, Broas M, Suramo I, et al. High-resolution computed tomography for the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 1998;27:358–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruskin JA, Gurney JW, Thorsen MK, et al. Detection of pleural effusions on supine chest radiographs. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987;148:681–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soldati G, Testa A, Sher S, et al. Occult traumatic pneumothorax: diagnostic accuracy of lung ultrasonography in the emergency department. Chest 2008;133:204–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray P, Birolleau S, Lefort Y, et al. Acute respiratory failure in the elderly: etiology, emergency diagnosis and prognosis. Crit Care 2006;10:R82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura BJ, Pezeshki B, Frack SA, et al. Feasibility of “limited” echo imaging: characterization of incidental findings. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1998;11:746–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willenheimer RB, Israelsson BA, Cline CM, et al. Simplified echocardiography in the diagnosis of heart failure. Scand Cardiovasc J 1997;31:9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore CL, Rose GA, Tayal VS, et al. Determination of left ventricular function by emergency physician echocardiography of hypotensive patients. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:186–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reissig A, Kroegel C. Sonographic diagnosis and Follow-up of pneumonia: a prospective study. Respiration 2007;74:537–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lichtenstein D, Mezière G. A lung ultrasound sign allowing bedside distinction between pulmonary edema and COPD: the comet-tail artefact. Intensive Care Med 1998;24:1331–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volpicelli G, Caramello V, Cardinale L, et al. Detection of sonographic B-lines in patients with normal lung or radiographic alveolar consolidation. Med Sci Monit 2008;14:CR122–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathis G, Blank W, Reissig A, et al. Thoracic ultrasound for diagnosing pulmonary embolism. A prospective multicenter study of 352 patients. Chest 2005;128:1531–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doveri M, Frassi F, Consensi A, et al. Ultrasound lung comets: new echographic sign of lung interstitial fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatismo 2008;60:180–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pezullo JA, Perkins AB, Cronan JJ. Symptomatic deep vein thrombosis: diagnosis with limited compression ultrasound. Radiology 1996;198:67–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansencal N, Vieillard-Baron A, Beauchet A, et al. Triage patients with suspected pulmonary embolism in the emergency department using a Portable ultrasound Device. Echocardiography 2008;25:451–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michelson E, Hollrah S. Evaluation of the patient with shortness of breath: an evidence based approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1999;17:221–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ 2008;337:a2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen MB, Sloth E, Larsen KM, et al. Transthoracic echocardiography for cardiopulmonary monitoring in intensive care. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2004;21:700–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lichtenstein D. General Ultrasound in the Critically Ill. 2nd edn Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 27.American College of Emergency Physicians Emergency ultrasound imaging criteria compendium. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:487–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danish Data Protection Agency The Act on Processing Personal Data. http://www.datatilsynet.dk/english/the-act-on-processing-of-personal-data/read-the-act-on-processing-of-personal-data/compiled-version-of-the-act-on-processing-of-personal-data/ (accessed 14 Apr 2012).

- 29.WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/17c.pdf (accessed 20 Mar 2012).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.