Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the study was to report the outcomes for cases of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) that received retinotomy and removal of subretinal proliferative tissue under direct visualization using retinal turnover.

Methods

Nineteen eyes with posterior and/or anterior grade C1–12 PVR that had undergone retinotomy and retinal turnover were reviewed. Main outcomes included the retinal reattachment rate, final best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), postoperative intraocular pressure, extent of retinotomy, and complications.

Results

Final retinal reattachment rates with silicone oil tamponade were 100%. The mean logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution (logMAR) BCVA was significantly improved (P = 0.001). Positive correlation was found between the extent of retinotomy and both preoperative logMAR BCVA (r = 0.663, P = 0.002) and postoperative logMAR BCVA (r = 0.619, P = 0.005). There was no correlation between the extent of retinotomy and the change in preoperative and postoperative logMAR BCVA (r = −0.267, P = 0.268). Negative correlation was found between preoperative logMAR BCVA and the change in logMAR BCVA (r = −0.587, P = 0.008). There was no correlation between the extent of retinotomy and the intraocular pressure at the final visit (r = −0.316, P = 0.188). Corneal decompensation due to silicone oil in the anterior chamber occurred in one eye.

Conclusion

Removal of subretinal proliferative tissue with retinal turnover seems to be an effective procedure.

Keywords: proliferative vitreoretinopathy, retinotomy, retinal turnover, subretinal proliferative tissue, under direct visualization

Introduction

Several surgical techniques exist for removing subretinal proliferative tissue during vitrectomy for proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR). When the subretinal proliferative tissue is in the form of branching bands and the extent of the tissue can be observed through the retina, the bands can be removed using forceps passed through preexisting retinal breaks or a small retinotomy site, as described by Lewis et al1 However, it is almost impossible to determine with accuracy the extent of subretinal proliferative tissue that is in the form of diffuse sheets through the retina. Removal of diffuse sheets of tissue through small retinotomy sites would likely lead to severe retinal damage, because multiple or posterior retinotomy sites might be unavoidable. Therefore, to remove diffuse sheets of subretinal proliferative tissue, it is sometimes necessary to make a peripheral extensive retinotomy and turn the retina over in order to grasp the proliferative tissue under direct visualization. This maneuver was first introduced by Machemer et al in 1986.2 Since then, many retinotomy/retinectomy cases have been reported for the treatment of PVR, but, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, only three reports have described the removal of a diffuse sheet of subretinal proliferative tissue under direct visualization by using retinal turnover.3–5 However, these reports did not provide intraoperative and postoperative information on the patients.

The purpose of this study was to describe a subset of PVR cases that required retinotomy and retinal turnover in order to remove subretinal proliferative tissue under direct visualization.

Patients and methods

Patient medical records that met the following criteria were reviewed retrospectively: all surgical procedures were performed by a single surgeon (AN) between February 2006 and November 2010; surgery was to treat posterior and/or anterior grade C1–12 PVR with subretinal proliferative tissue in the form of a diffuse sheet (type 3: subretinal).6 Vitreoretinal surgery that included retinotomy and retinal turnover was performed in order to remove subretinal proliferative tissue under direct visualization. Prior to surgery, each patient was informed about the risks and benefits of the surgery and the possibility of receiving retinotomy, and written informed consent was obtained in accordance with Kanazawa University (Kanazawa, Japan) institutional guidelines. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Kanazawa University and followed the tenets of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

All patients underwent a comprehensive ophthalmic examination at the preoperative and postoperative visits, including measurement of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), noncontact tonometry, slit lamp examination, and fundus examination. PVR was characterized intraoperatively and graded according to the Retina Society classification system.6 Optical coherence tomography examination was performed postoperatively, if possible, using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (3D OCT-1000; Topcon Medical Systems Inc, Tokyo, Japan) to confirm the postoperative macular status. Histopathological examination of the excised subretinal tissue obtained following surgery was performed in some cases.

Phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation was performed prior to pars plana vitrectomy on all phakic eyes, including two eyes with hyper mature cataract. In aphakic cases, peripheral iridectomy was done using a vitreous cutter in the lower quadrant. All patients underwent a 20-gauge or 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy. A complete posterior vitreous detachment up to the vitreous base was surgically created, if not already present, and 360-degree vitreous base shaving under scleral depression was performed. After removal of the epiretinal proliferative membranes, an extensive peripheral retinotomy was performed at the peripheral region, and the retina was turned over to provide direct surgical access to the subretinal proliferative tissue, which was then removed with forceps. The extent of retinotomy was determined as necessary to provide direct visualization of the subretinal proliferative tissue and to allow the removal of the tissue safely. The nonfunctional peripheral retina anterior to the retinotomy was then excised with the vitreous cutter.2,4,5,7–16 After the anterior and posterior surfaces of the retina and subretinal space were meticulously cleaned, the retina was flattened with perfluorocarbon liquid (PFCL; Perfluoron®; Alcon Laboratories Inc, Fort Worth, TX), and two to three rows of endolaser photocoagulation was applied to the retinotomy edge. Silicone oil (SO; 1000 cSt) (Silikon 1000™; Alcon) was injected as an intraocular tamponade agent in all eyes, followed by either direct PFCL/SO exchange without an intermediate air exchange17 or indirect PFCL/SO exchange with an intermediate air exchange. In most cases, a combined encircling buckle (3 mm-wide silicone band) was placed at the equator of eyes that had no preexisting encircling buckle. An eye with PVR caused by a macular hole due to high myopia underwent macular buckling using a special macular explant developed by Ando et al.18 No position restrictions were given postoperatively. SO was removed only after the retina had remained attached for at least 3 months postoperatively and if the patient desired the oil removal procedure.

Both the initial and final retinal reattachment rates were evaluated. The initial reattachment rate represents the reattachment rate after the first vitrectomy with retinotomy for retinal turnover, and the final reattachment rate represents the reattachment rate at the final visit. Differences between preoperative and postoperative BCVA were evaluated by a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Correlation between two factors among the extent of retinotomy (degrees), preoperative BCVA, postoperative BCVA, and change between preoperative and postoperative BCVA was assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. The correlation between the extent of retinotomy and both postoperative intraocular pressure (IOP) at the final visit (Spearman’s correlation coefficient) and the pucker removal rate (Mann–Whitney U test) were also assessed.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Visual acuity was converted into logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution (logMAR) units for statistical analysis. The decimal equivalent of 0.014 and 0.005 was used for counting fingers and hand motions, respectively, to measure visual acuity according to Schulze-Bonsel et al19 LogMAR of light perception vision was assigned 2.8, as described by Grover et al.20 A change greater than 0.3 logMAR units between preoperative and postoperative visual acuity was classified as an improvement or a decrease in BCVA, while BCVA within 0.3 logMAR units was rated as unchanged.

Results

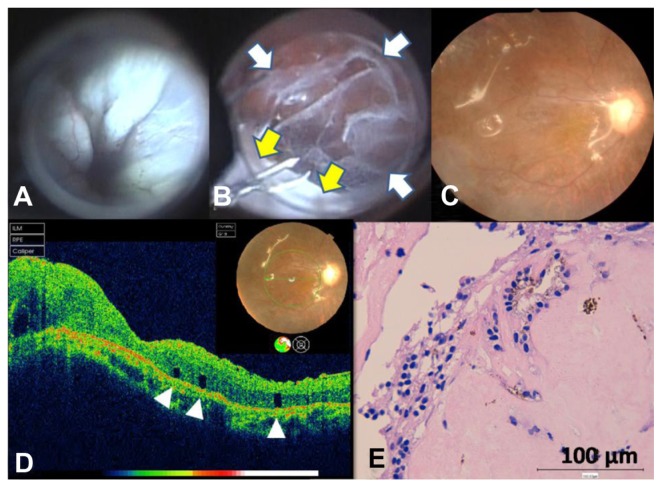

In this study, 19 eyes of 19 patients were enrolled. Preoperative characteristics are shown in Table 1. Performed treatments are shown in Table 2. The median follow-up time was 41 months (range 7–64 months). The representative case is shown in Figure 1. A video file is also available.

Table 1.

Preoperative characteristics of the patients who underwent vitreoretinal surgery that included retinotomy and retinal turnover to remove subretinal proliferative tissue under direct visualization (N = 19)

| Gender | 10 male (52.6%) |

| 9 female (47.4%) | |

| Mean age (±SD, range) | 44.6 (±20.6, 11–73) years |

| BCVA | |

| Light perception | 3 eyes (15.8%) |

| Hand motions | 6 eyes (31.6%) |

| Counting fingers | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| 0.01–0.09 | 6 eyes (31.6%) |

| ≥0.1 | 3 eyes (15.8%) |

| PVR | |

| Grade CP 1–12 + CA 1–12 | 16 eyes (84.2%) |

| Grade CP 1–12 | 3 eyes (15.8%) |

| Cause of PVR | |

| Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment | 10 eyes (52.6%) |

| Self-injury | 4 eyes (21.1%) |

| Ocular contusion | 2 eyes (10.5%) |

| MHRD due to high myopia | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| Falciform retinal detachment | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| Endogenous infectious endophthalmitis | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| Patients with a mental disorder | 5 eyes (26.3%) |

| Number of previous vitreoretinal surgeries | |

| None | 9 eyes (47.4%) |

| One | 5 eyes (26.3%) |

| Two | 2 eyes (10.5%) |

| Three | 2 eyes (10.5%) |

| Four | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| Number of previous retinotomy without retinal turnover procedure | |

| None | 16 eyes (84.2%) |

| One | 2 eyes (10.5%) |

| Two | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| Previous scleral encircling buckle | 5 eyes (26.3%) |

| Previous silicone oil injection | 5 eyes (26.3%) |

| Lens status | |

| Clear crystalline lens | 5 eyes (26.3%) |

| Cataract | 2 eyes (10.5%) |

| IOL | 11 eyes (57.9%) |

| IOL luxation | 1 eye (5.3%) |

Abbreviations: BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; CA, anterior grade C; CP, posterior grade C; IOL, intraocular lens; MHRD, retinal detachment caused by macular hole; PVR, proliferative vitreoretinopathy; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Performed treatment (N = 19)

| Number of retinotomy with retinal turnover | |

| One | 15 eyes (78.9%) |

| Two | 4 eyes (21.1%) |

| Intervals between retinotomy with retinal turnover procedure | |

| 1 month | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| 2 months | 2 eyes (10.5%) |

| 3 months | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| Final extent of retinotomy | |

| 360 degrees | 10 eyes (52.6%) |

| 300 degrees | 2 eyes (10.5%) |

| 270 degrees | 3 eyes (15.8%) |

| 240 degrees | 2 eyes (10.5%) |

| 150 degrees | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| 130 degrees | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| Combined surgery | |

| Scleral buckle | 11 eyes (57.9%) |

| Macular buckle | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| IOL implantation | 7 eyes (36.8%) |

| IOL extraction | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| SO tamponade | 19 eyes (100%) |

| SO exchange at initial surgery | |

| Direct PFCL/SO | 17 eyes (89.5%) |

| Indirect PFCL/SO | 2 eyes (10.5%) |

| SO exchange at second surgery | |

| Direct PFCL/SO | 3 eyes (15.8%) |

| Indirect PFCL/SO | 1 eye (5.3%) |

Abbreviations: IOL, intraocular lens; PFCL, perfluorocarbon liquid; SO, silicone oil.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative and postoperative view of a 61-year-old male with long-standing rhegmatogenous retinal detachment with epiretinal and subretinal proliferation. The preoperative visual acuity was counting fingers. He was diagnosed with posterior grade C12 and anterior grade C12 proliferative vitreoretinopathy (type 3: subretinal) and underwent pars plana vitrectomy with retinotomy for retinal turnover and retinal relaxing. (A) Intraoperative view. The retina lacked elasticity despite removal of epiretinal proliferative tissue. (B) Intraoperative view. The 360-degree retinotomy allowed for retinal turnover and removal of a diffuse sheet of subretinal proliferative tissue under direct visualization. Almost the entire subretinal space is covered with a diffuse sheet of subretinal tissue (white arrows) and the area at the lower left is the turned-over retina (yellow arrows). (C) Postoperative fundus photograph 4 months after surgery. (D) The postoperative spectral-domain optical coherence tomography image 3 months after surgery shows loss of the photoreceptor inner and outer segment junction and the external limiting membrane of the macula. White arrowheads show the migrated perfluorocarbon liquid. (E) Histopathological examination of the surgically excised subretinal tissue reveals fibrous connective tissue with pigmented cells. There are small epithelial cells with ovary-shaped nucleus, arranged in clumps (hematoxylin and eosin).

Previous procedures

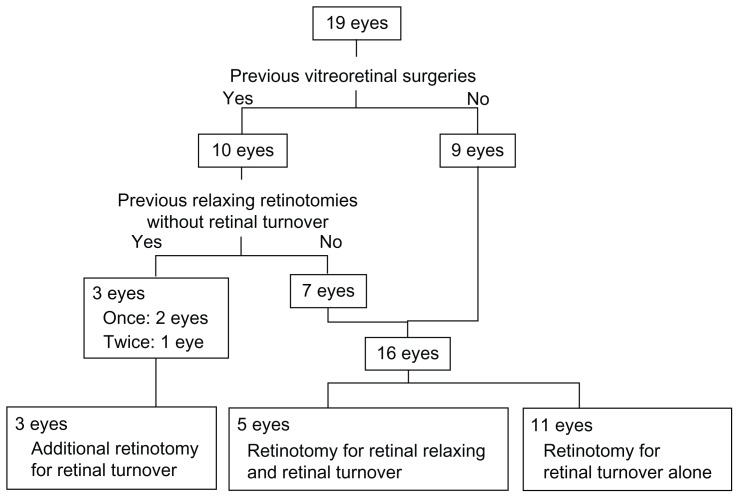

Figure 2 shows the relevant ocular surgical history of the 19 cases. Of the nine cases with no previous vitreoretinal surgery history, six eyes had been left untreated and the patients had reported decreased visual acuity, while change in visual acuity in three eyes was unreported because the patients each had a mental disorder.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of cases that underwent retinotomy for retinal turnover alone and retinal turnover combined with retinal relaxing.

Retinotomy and retinal turnover

Retinotomy was performed in five eyes to turn the retina over as well as to relax the retina and performed in eleven eyes solely to turn the retina over and remove the subretinal proliferative tissue. For three eyes which had undergone previous relaxing retinotomy, additional retinotomy was performed.

The circumferential extent of retinotomy that was required to remove the subretinal tissue under direct visualization was the same as that required to relax the retina in one eye. In 18 eyes, the extent of retinotomy needed for removal of subretinal tissue exceeded the extent needed to relax the retina. In two eyes, the removal of subretinal tissue was attempted through a small retinotomy site, as described by Lewis et al.1 However, the retinal fold still remained after the removal of as much subretinal tissue as possible through the small retinotomy site, and the remaining subretinal tissue was thought to be the cause of the fold. It was then judged necessary to observe subretinal tissue under direct visualization and the extensive peripheral retinotomy with retinal turnover was performed.

Buckling and combination procedures

Of the 19 eyes, 16 underwent retinotomy and encircling scleral buckling, two had 360-degree retinotomy without buckling, and one eye with PVR caused by a macular hole due to severe myopia had 360-degree retinotomy and macular buckling.

Anatomical results

The initial retinal reattachment rate with SO tamponade was 78.9% (15/19 eyes), as shown in Table 3. The final retinal reattachment rate was 100% (19/19 eyes), including 14 eyes in which SO remained and five eyes in which SO was removed.

Table 3.

Anatomical and functional results and complications (N = 19)

| Median follow-up (range) | 41 (7–64) months |

| Initial retinal reattachment rate (including SO remained) | 78.9% (15/19 eyes) |

| Final retinal reattachment rate (including SO remained) | 100% (19/19 eyes) |

| BCVA at the final visit | |

| Light perception | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| Hand motions | 0 eyes (0%) |

| Counting fingers | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| 0.01–0.09 | 9 eyes (47.4%) |

| ≥ 0.1 | 8 eyes (42.1%) |

| Change in preoperative and postoperative BCVA* | |

| Improvement | 12 eyes (63.2%) |

| Unchanged | 6 eyes (31.6%) |

| Decreased | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| Mean IOP at the final visit (range) | 12.2 (7.0–19.0) mmHg |

| Pucker removal | 8 eyes (42.1%) |

| Corneal decompensation | 1 eye (5.3%) |

| SO removal | 5 eyes (26.3%) |

Notes:

Improvement in best-corrected visual acuity was defined as a decrease in logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution units of >0.3, unchanged was defined as a change within 0.3 logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution units, and a decrease was defined as an increase in logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution units of >0.3.

Abbreviations: BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; IOP, intraocular pressure; SO, silicone oil.

Functional results

The mean BCVA was significantly improved from 1.88 ± 0.74 logMAR units preoperatively to 1.26 ± 0.65 log- MAR units at the final visit (P = 0.001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) (Table 3). The final visual acuity improved in twelve eyes (63.2%), remained unchanged in six eyes (31.6%), and decreased in one eye (5.3%).

Positive correlation was found between the final extent of retinotomy and both preoperative logMAR BCVA (r = 0.663, P = 0.002, Spearman’s correlation coefficient) and postoperative logMAR BCVA (r = 0.619, P = 0.005, Spearman’s correlation coefficient); therefore, a negative correlation existed between the final extent of retinotomy and both preoperative and postoperative decimal BCVA. There was no correlation between the final extent of retinotomy and the change in preoperative and postoperative logMAR BCVA (r = −0.267, P = 0.268, Spearman’s correlation coefficient).

Positive correlation was found between preoperative log- MAR BCVA and postoperative logMAR BCVA (r = 0.573, P = 0.01, Spearman’s correlation coefficient). Negative correlation was found between preoperative logMAR BCVA and the change in preoperative and postoperative logMAR BCVA (r = −0.587, P = 0.008, Spearman’s correlation coefficient); therefore, a negative correlation existed between preoperative decimal BCVA and the change in decimal BCVA. There was no correlation between postoperative logMAR BCVA and the change in preoperative and postoperative logMAR BCVA (r = 0.247, P = 0.307, Spearman’s correlation coefficient).

The three cases with posterior grade C PVR without anterior grade C PVR had relatively good preoperative BCVA (0.04, 0.3, and 0.4), two of which underwent SO removal. Postoperative BCVA was unchanged compared to the preoperative BCVA in all three cases. The sample size was too small to perform statistical analysis comparing these cases to those with both posterior and anterior grade C PVR.

Postoperative complications

The mean IOP at the final visit was 12.2 mmHg (range: 7.0–19.0 mmHg) (Table 3). There were no cases of ocular hypotension (<6 mmHg) or hypertension (>20 mmHg) that required medication at the final visit. There was no correlation found between the final extent of retinotomy and IOP at the final visit (r = −0.316, P = 0.188, Spearman’s correlation coefficient). Corneal decompensation due to SO in the anterior chamber occurred in one eye. Additional surgery for the removal of pucker was necessary in eight eyes. There was no correlation found between the final extent of retinotomy and the pucker removal rate (P = 0.303, Mann– Whitney U test).

Discussion

To gain direct surgical access to a diffuse sheet of subretinal proliferative tissue, extensive peripheral retinotomy, retinal turnover, and removal of the proliferative tissue under direct visualization has become a relatively simple procedure, especially since the development of direct PFCL/SO exchange by Mathis et al.17 However, many vitreoretinal surgeons may be apprehensive about performing extensive retinotomy in cases of advanced PVR, because it might lead to ocular hypotension or to much more severe PVR. Previous reports on retinotomy for PVR showed that the final retinal reattachment rate varied from 52% to 98.1%.3–5,9–16,21–25 In the present study, the final retinal reattachment rate was 100%. This was achieved by SO remaining in most of the eyes at the final visit. Oil remaining in the eyes was unavoidable, like that of other reports on retinotomy.3–5,9,10,12–14,16,21–24

The association between the extent of retinotomy and the final retinal reattachment rate could not be evaluated, which was reported to have no association in other studies,3,9,25 because retinal reattachment was achieved in all cases in the present study. However, the extent of retinotomy may not be related to the significance of reproliferation because there was no correlation between these two factors.

No cases developed ocular hypotension in the present series. The hypotension rate after extensive retinotomy ranged from 0% to 58% in previous studies,3–5,9–16,21–24 and many reported less than 10%.3,10,13,16,21 In addition, no association has been reported between the extent of retinotomy and postoperative ocular hypotension,3,9,21 and results from the present study were in agreement.

SO injection was performed in all eyes. This was judged necessary based on previous reports in which the reattachment rate after using SO was better than that seen after using gas tamponade in extensive retinotomies.11,13 No postoperative position restrictions were given because SO was injected almost full and all of the retinal breaks, no matter where they were located, would be tamponaded to a certain degree due to the patients’ various positioning.

The SO removal rate in previous reports ranged from 0% to 73.7%,3–5,9,10,12–14,16,21–24 and in some reports reinstillation of SO was required because ocular hypotension developed after oil removal.3,4 In the present study, one eye that showed corneal decompensation due to SO in the anterior chamber had normal IOP during the follow-up and IOP of 10.1 mmHg at the final visit. Migration of SO into the anterior chamber may occur secondary to ciliary hyposecretion while the IOP simultaneously stays normal because of the SO tamponade. Oil removal is required should postsurgical ocular hypertension develop. However, because the procedure is not without risk, removing the oil in cases of advanced PVR when the postoperative IOP remains normotensive may not be optimal case management. Oil removal was advised, especially to patients who had good BCVA, to avoid oil-related hyperopia and anisometropia. No case of ocular hypertension required antiglaucomatous drops, and not many patients strongly desired or requested SO removal. The oil remained in place in most of cases, in fact for more than 3 years in eleven eyes and more than 5 years in four eyes. Eyeglasses were prescribed for the patients who decided not to undergo oil removal.

Because encircling scleral buckling was performed in most eyes (84.2%) and retinal reattachment rate was 100%, the association between the combined encircling scleral buckling and the retinal reattachment rate could not be evaluated. The efficacy of combined encircling still remains controversial. Quiram et al13 and Han et al23 reported no association between combined encircling and retinal reattachment rate, while Han et al23 also reported a positive association between encircling and postoperative visual acuity. The encircling scleral buckling was not performed for the two most recent cases with 360-degree retinotomy because of the uncertainty of the efficacy of combined encircling and its invasiveness. However, all three cases with 360-degree retinotomy achieved retinal reattachment without encircling scleral buckling. This result may lead to discussion about whether encircling scleral buckling is necessary for cases with 360-degree retinotomy.

Additional surgeries were performed for pucker removal in eight eyes (42.1%), a result within the 10% to 63% range in previous reports.3,4,9–12,14,16,21,22

The overall mean postoperative BCVA was significantly improved, and the final visual acuity was no worse than the preoperative acuity in 94.7% of the eyes, a result which may indicate successful treatment even considering the cataract surgery for two eyes with hyper mature cataract. Positive correlation was found between preoperative and postoperative BCVA, which was in agreement with previous reports.9,23 Moreover, a negative correlation was found between preoperative BCVA and the change between preoperative and postoperative BCVA, a result which suggests that better improvement could be expected in cases with worse preoperative BCVA. Therefore, in cases which seem inoperable, retinotomy sufficiently extensive to allow the retina to be turned over and the subretinal proliferative tissue removed under direct visualization may well be worth trying. The authors also believe that, unfortunately, there may be no alternative to this procedure for those cases.

Bovey et al3 reported no association between the extent of retinotomy and postoperative visual acuity, while many others reported a negative correlation,1,9,21–23 a result which was confirmed in the present study.

A negative correlation was also found between the extent of retinotomy and both preoperative and postoperative decimal BCVA. However, there was no association between the final extent of retinotomy and the change in BCVA. The extent of retinotomy did not seem to interfere with the improvement in BCVA and the retinotomy must be wide enough to allow removal of all the subretinal proliferative tissue. The retina redetached in four eyes due to reproliferation of the subretinal tissue and those patients underwent a second surgery. The extent of the initial retinotomy was smaller than that of the second retinotomy, which may suggest that the initial retinotomy was too small and resulted in incomplete removal of subretinal tissue.

In the present study, there were nine eyes (47.4%) with no history of previous vitreoretinal surgery. Federman and Eagle4 and Tsui and Schubert5 reported on retinotomy with retinal turnover for PVR cases with a history of previous vitreoretinal surgery, and Bovey et al3 reported four cases of this procedure without detailed descriptions on the previous surgeries. In these previous reports, the procedures seemed to be performed mainly on reoperation cases.3–5 The authors suggest that retinotomy with retinal turnover and removal of the subretinal proliferative tissue should be an accepted technique even for the initial surgery. In severe cases that might have been judged inoperable, there might be some cases that would result in retinal reattachment and might be prevented from phthisis bulbi even with SO tamponade.

In five cases (26.3%) of the present study, the patient had an associated mental disorder, of which four eye injuries were self-inflicted. Tan et al21 reported two cases of mental disability out of 123 eyes with retinotomy (1.6%), which is a much smaller rate than the present study.

The main difference between the present study and previous reports on retinotomy was the purpose of the retinotomy. For the cases of anterior PVR, retinotomy is usually performed to relax the retina in order to obtain retinal reattachment. However, PVR grade C of subretinal type requires retinotomy to gain surgical access to the subretinal space and remove the subretinal proliferative tissue under direct visualization. In all cases in the present series, the extent of retinotomy required to remove the subretinal tissue was no less than the extent necessary to relax the retina. Furthermore, although the retinotomy was judged necessary only to turn the retina over and remove the subretinal tissue in eleven eyes, retinotomy may have contributed to the relaxing effect in these cases. Surgeons may hesitate to perform this type of surgery on cases which do not necessarily require a relaxing retinotomy but require removal of subretinal tissue. It can be difficult to judge whether the subretinal tissue can be removed from a small retinotomy site1 or if extensive retinotomy to turn the retina over is necessary for complete removal. In two cases of the present series, extensive retinotomy and the observation of subretinal tissue under direct visualization were judged necessary intraoperatively after the initial attempt of subretinal tissue removal from a small retinotomy site because the removal of the tissue was incomplete and the retinal fold still remained. This caused unnecessary damage to the retina and extended duration of surgery.

Potential limitations of this study are that this was a retrospective study with a relatively small sample size and that all patients received SO injection. For complicated PVR with repeat recurrence of retinal detachment, the diffuse sheet of subretinal proliferative tissue may be responsible and removal of it may be an efficient solution. However, a limited number of patients need this type of surgery and it is not possible to experience many of these cases in one center.

Conclusion

This study showed a 100% final retinal reattachment rate and significant improvement of the mean BCVA. Some severe PVR cases that might have been judged inoperable may benefit from this technique. However, there remain some cases where it is unclear if the subretinal tissue can be removed through a small retinotomy site or if an extensive retinotomy is necessary. Further studies are needed to evaluate the indication and prognosis of this promising technique.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Lewis H, Aaberg TM, Abrams GW, McDonald HR, Williams GA, Mieler WF. Subretinal membranes in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(9):1403–1415. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machemer R, McCuen BW, 2nd, de Juan E., Jr Relaxing retinotomies and retinectomies. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;102(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bovey EH, De Ancos E, Gonvers M. Retinotomies of 180 degrees or more. Retina. 1995;15(5):394–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Federman JL, Eagle RC., Jr Extensive peripheral retinectomy combined with posterior 360 degrees retinotomy for retinal reattachment in advanced proliferative vitreoretinopathy cases. Ophthalmology. 1990;97(10):1305–1320. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsui I, Schubert HD. Retinotomy and silicone oil for detachments complicated by anterior inferior proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(9):1228–1233. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.140988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Machemer R, Aaberg TM, Freeman HM, Irvine AR, Lean JS, Michels RM. An updated classification of retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112(2):159–165. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76695-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourke RD, Dowler JG, Milliken AB, Cooling RJ. Perimetric and angiographic effects of retinotomy. Aust NZJ Ophthalmol. 1996;24(3):245–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1996.tb01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourke RD, Cooling RJ. Vascular consequences of retinectomy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114(2):155–160. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130149006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grigoropoulos VG, Benson S, Bunce C, Charteris DG. Functional outcome and prognostic factors in 304 eyes managed by retinectomy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245(5):641–649. doi: 10.1007/s00417-006-0479-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Silva DJ, Kwan A, Bunce C, Bainbridge J. Predicting visual outcome following retinectomy for retinal detachment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(7):954–958. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.131540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tseng JJ, Barile GR, Schiff WM, Akar Y, Vidne-Hay O, Chang S. Relaxing retinotomy on surgical outcomes in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(4):628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banaee T, Hosseini SM, Eslampoor A, Abrishami M, Moosavi M. Peripheral 360 degrees retinectomy in complex retinal detachment. Retina. 2009;29(6):811–818. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31819bab1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quiram PA, Gonzales CR, Hu W, et al. Outcomes of vitrectomy with inferior retinectomy in patients with recurrent rhegmatogenous retinal detachments and proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(11):2041–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faude F, Lambert A, Wiedemann P. 360 degrees retinectomy in severe anterior PVR and PDR. Int Ophthalmol. 1998–1999;22(2):119–123. doi: 10.1023/a:1006254721964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blumenkranz MS, Azen SP, Aaberg T, et al. Relaxing retinotomy with silicone oil or long-acting gas in eyes with severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Silicone Study Report 5. The Silicone Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116(5):557–564. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han DP, Rychwalski PJ, Mieler WF, Abrams GW. Management of complex retinal detachment with combined relaxing retinotomy and intravitreal perfluoro-n-octane injection. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118(1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72838-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathis A, Pagot V, Gazagne C, Malecaze F. Giant retinal tears. Surgical techniques and results using perfluorodecalin and silicone oil tamponade. Retina. 1992;12(Suppl 3):S7–S10. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199212031-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ando F, Ohba N, Touura K, Hirose H. Anatomical and visual outcomes after episcleral macular buckling compared with those after pars plana vitrectomy for retinal detachment caused by macular hole in highly myopic eyes. Retina. 2007;27(1):37–44. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000256660.48993.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulze-Bonsel K, Feltgen N, Burau H, Hansen L, Bach M. Visual acuities “hand motion” and “counting fingers” can be quantified with the Freiburg visual acuity test. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(3):1236–1240. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grover S, Fishman GA, Anderson RJ, et al. Visual acuity impairment in patients with retinitis pigmentosa at age 45 years or older. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(9):1780–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan HS, Mura M, Oberstein SY, de Smet MD. Primary retinectomy in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(3):447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iverson DA, Ward TG, Blumenkranz MS. Indications and results of relaxing retinotomy. Ophthalmology. 1990;97(10):1298–1304. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han DP, Lewis MT, Kuhn EM, et al. Relaxing retinotomies and retinectomies. Surgical results and predictors of visual outcome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108(5):694–697. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070070080039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alturki WA, Peyman GA, Paris CL, Blinder KJ, Desai UR, Nelson NC., Jr Posterior relaxing retinotomies: analysis of anatomic and visual results. Ophthalmic Surg. 1992;23(10):685–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morse LS, McCuen BW, 2nd, Machemer R. Relaxing retinotomies. Analysis of anatomic and visual results. Ophthalmology. 1990;97(5):642–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]