Abstract

Objectives

To report on a participatory research process in southwest Alaska focusing on youth involvement as a means to facilitate health promotion. We propose youth-guided community-based participatory research (CBPR) as way to involve young people in health promotion and prevention strategizing as part of translational science practice at the community-level.

Study design

We utilized a CBPR approach that allowed youth to contribute at all stages.

Methods

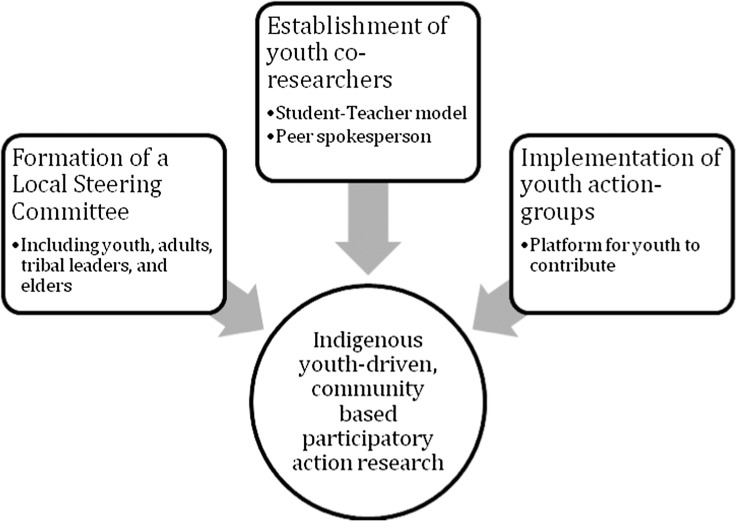

Implementation of the CBPR approach involved the advancement of three key strategies including: (a) the local steering committee made up of youth, tribal leaders, and elders, (b) youth-researcher partnerships, and (c) youth action-groups to translate findings.

Results

The addition of a local youth-action and translation group to the CBPR process in the southwest Alaska site represents an innovative strategy for disseminating findings to youth from a research project that focuses on youth resilience and wellbeing. This strategy drew from two community-based action activities: (a) being useful by helping elders and (b) being proud of our village.

Conclusions

In our study, youth informed the research process at every stage, but most significantly youth guided the translation and application of the research findings at the community level. Findings from the research project were translated by youth into serviceable action in the community where they live. The research created an experience for youth to spend time engaged in activities that, from their perspectives, are important and contribute to their wellbeing and healthy living. Youth-guided CBPR meant involving youth in the process of not only understanding the research process but living through it as well.

Keywords: Alaska Native, Yup'ik Eskimo, youth-guided, community-based participatory research, youth prevention, translational science

Youth in circumpolar indigenous communities experience a greater prevalence of health and mental health disparities relative to youth in urban and non-indigenous communities (1–6). Much of the current research attempting to address these health disparities among Arctic youth is at the population level (1,5–8). Several studies have identified association of cultural disruption, acculturation stress, and identity struggle, with youth health disparities in circumpolar communities (9–11). Other studies have shown a link of cultural continuity, enculturation, and community control to resilience and well-being among Arctic indigenous populations (12–15). What is evident from the research are the ways that youth in the Arctic remain on the forefront of social change, global influence, and the conflicting expectations between dominant society and indigenous communities (15,16).

Community based participatory research (CBPR) is an approach to research that aims to facilitate co-learning and co-partnering between researchers and community members throughout the research project to promote community-capacity building (17). CBPR encourages researchers to move from doing research about a specific population to doing research with community members (18). Many listings of the characteristics of CBPR have been enumerated; relevant to the current consideration is conceptualizing the research process on the community level, building on the strengths and expertise of community members, and empowering community members to participate as co-researchers (18–20). CBPR projects have demonstrated particularly positive impacts with indigenous and other historically disenfranchised populations (19,21,22). Youth involvement in CBPR is an emerging focus in the literature (23–27) yet few examples exist of youth involvement in indigenous research (28–30).

Youth involvement in CBPR

It is well established that community participation is an essential component in health promotion and health intervention (31). Just how to achieve community participation in activities that aim to impact health outcomes in populations of focus is less well established (32). Many challenges present themselves to researchers aiming to conduct CBPR projects, and these challenges are increased when a project aims to involve a subgroup within a disenfranchised population that traditionally has not participated as equals in a local setting (33). Youth are an example of one such subgroup that presents special challenges for researchers aiming to achieve authentic participation in CBPR projects (25).

Researchers have found that youth participation in health-related research and promotion can take on different forms (26). Hart's (34) ladder of youth participation is one of the most classic illustrations of the kinds of typologies that exist to explain youth involvement. Hart's typology moves from “manipulation” the “lowest” level of youth empowerment in a project essentially characterized by youth being told what is good for them; to “child-initiated, shared decisions with adults.” In Hart's typology the “highest” level of youth involvement is the one where youth are empowered to make decisions and to have their decisions carried out by the adults guiding the administration of the program or research. Recently, researchers have begun to move away from Hart's (34) linear directional model to alterative typologies that use an empowerment framework. Wong et al. (26) identifies five types of youth participation: vessel, symbolic, pluralist, independent and autonomous. These 5 types fall along a continuum defined by the degree of participation. Wong et al. (26) envision an optimal centre in any project where power and participation is shared between participating groups in the research in varying degrees along the continuum. While some research might suggest that increasing egalitarian relations between youth and adults is optimal for healthy development (35). Wong et al. (26), acknowledge egalitarianism is not always appropriate or even possible in some contexts. Despite differences in the ways that youth are involved, these youth researchers attest to increased positive impacts when authentic and active youth involvement is achieved.

Youth involvement in circumpolar CBPR

The purpose of the Circumpolar Indigenous Pathways to Adulthood (CIPA) project is to explore youth perspectives on stressors and well-being in Alaskan Inupiat, Alaskan Yup'ik, Canadian Inuit, Norwegian Sámi, and Siberian Eveny community settings. CIPA uses CBPR strategies to engage youth and other community members in each community in partnerships for health. This paper reports on the local youth-driven CBPR research process with the CIPA site located in Southwest Alaska, undertaken with youth from a Yup'ik Eskimo community.

The health research approach reported in this paper comes out of a long history of doing CBPR with Alaska Native people (36–38) and CIPA builds upon ongoing CBPR intervention work simultaneously occurring in the Yup'ik community (38); however, CIPA involves a more explicit focus on youth perspectives and a youth-guided process than the intervention work. This paper describes strategies used within our CBPR process to increase youth involvement in the research with a particular focus on the local dissemination phase of the research. We describe some of the ways the approach impacted the youth in the community. We propose a three-tiered youth-guided CBPR process to involve young people in circumpolar indigenous communities in health promotion and prevention strategizing as part of translational science practice at the community-level.

Material and methods

Setting

The Yup'ik co-researcher, co-partner community is located in South-western Alaska. Villages in this region are accessible via airplane year round. When the Yukon River thaws villages are accessible by boat. There are no roads connecting the villages to other communities. However, during the winter months, an ice road allows for snow machine travel between villages. Village population in Southwest Alaska ranges from 200 to 1,100 of which on average 95% are Alaska Native or American Indian.

CBPR methods

Implementation of a local CBPR approach was facilitated through the use of three key strategies: (a) formation of a local steering committee made up of youth, adults, tribal leaders, and elders, (b) establishment of youth-researcher partnerships, and (c) implementation of youth action-groups to translate findings during dissemination into community action. These strategies are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Indigenous youth driven community based participatory action research model.

Through the local CBPR process, after the formation of the LSC and establishment of youth co-researchers, the project aimed to conduct 20 life history interviews with youth between the ages of 11 and 18 years old. Twenty-five youth were interviewed and over 40 members of the community became involved in the CBPR process. Institutional and tribal review boards approved this study.

Formation of a local steering committee

The initial local steering committee (LSC) was comprised of adults and elders involved in ongoing research in the community (38). During the project, the LSC evolved to cultivate youth community member involvement. The transformation began when we presented the project to youth at the school. We then invited interested youth to attend LSC meetings. This resulted in a core group of youth, adults, and elders as contributing members of the LSC. The LSC included youth in its key decision making on all aspects of the project, from the development of the youth interview protocol to the selection of the youth interviewers (local community members or outside researchers), and youth interviewees to dissemination of findings.

Establishment of youth-researcher partnerships

Youth-researcher partnerships emerged through youth involvement at the LSC level. The enhanced understanding of the project established through youth work on the LSC further involved youth in the research process and involved them in collaborative relationships with the university researchers. These youth-researcher partnerships provided a model to increase egalitarian relations between young people and all adults working on the project. Traditionally, youth involvement in Yup'ik communities bears resemblance to what Wong et al. (26), in their continuum typify as vessel (39,40). Youth are perceived as “empty vessels” needing to be “filled up” with local, community knowledge of their culture and world. The emerging youth-researcher partnerships bridged this traditional boundary. In some ways, our model was the teacher-student relationship with teachers, who typically also come from outside of the community. However, the health research project took the experience outside of the classroom and demonstrated how youth can become more active participants in community action through the CBPR process.

Youth co-researchers completed training in research ethics, assisted in recruitment of youth life history participants, encouraged youth involvement by way of talking to other youth about the project to explain its goals and purpose, and co-facilitated dissemination activities. Research ethics training, led by principle investigators, followed institutional review board approved field researcher curriculum created by Center for Alaska Native Health Research. Employing youth-researchers in dissemination activities shifted power back to the youth. Previously, it was the adults that talked to the youth in the community about the research, but with youth as co-researchers, other young community members found their peers talking to them about the project.

Implementation of youth action groups

Youth became actively involved in the translation of preliminary findings in several ways. During data analysis, two youth-action groups were formed by gender to discuss conceptual themes emerging from the data. This made the life history analysis process accessible to the youth and encouraged involvement. Youth assisted in the analysis of life history data by enriching findings with local interpretations and ensuring that our conceptual understandings did not stray from local experiences. We found that during this exercise the male group actively engaged in interpreting data and were willing to share in the group setting. On the other hand, when working with females, we learned the group setting did not function in the same way, and that to engage them we needed to instead seek one-on-one interaction with female community co-researchers, during which times they would readily provide rich interpretative input.

Results

The youth-driven elements of the CBPR process described here resulted in innovative action dissemination that collaboratively transformed research findings into action. Two community-based action activities, being useful by helping elders and being proud of our village, were jointly implemented through the youth-researcher partnerships to show other young participants strategies for being healthy through doing what had been learned from the research.

Through their involvement, youth told us not only what was important to them, they also provided key information about appropriate and meaningful contexts to give what we had learned as researchers back to their community. For example, a 17-year-old interweaves the importance of culture and helping others as he sees a contemporary challenge of village life:

| Interviewer: | So what do you think the difference is between being Yup'ik today and being old time Eskimo? |

| Male: | To me it's the same. We work hard. It's what we Yup'iks are supposed to do, work hard, focus on things what we have to do in life. Be friends with one another, but being friends with one another and helping is slowly fading away. Here I'm trying to help others but they don't want my help. They say they can do it on their own and when I see them having a hard time carrying some things, I just say to hell with that. I'm just going to go over there and help. So I go over there and help, bring some bags to their house. They say thank you. I am trying to keep the culture alive, that's what I'm doing and I'm still doing it today. |

Youth also offer suggestions for improving life in their community:

| Interviewer: | So you like living here in village. What makes it good? |

| Male: | Hunting and we can go out. I don't need to worry about people. |

| Interviewer: | What do you think would make it better here? |

| Male: | Get more cops because lots of kids stay out of school. They always spray paint stuff. They spray painted that door over there. |

We learned from youth participants in the project that being useful to others was part of living a culturally healthy life and contributes to well-being. While giving a project update to the school principal, she informed us about recently cut wood, cleared for the new school site. The LSC were consulted about this as an opportunity to deliver wood to elders as a way of demonstrating a finding from the research that involved “being useful.” The youth would participate in the activity, and then afterwards, there would be discussion of the research outcomes that identified being useful to others as a strategy for positive health and living cultural values. Through this type of youth action, research data and findings were put through a process of community-level translation by youth and for youth that became a critical part of the local dissemination strategy.

The first youth action group activity developed was being useful by helping elders. The activity was announced throughout the school. Youth, after school, organized in a classroom and formed the action group. Elders from the LSC shared with the youth teachings on the traditional Yup'ik cultural value regarding the importance of taking care of each other. Youth co-researchers assisted with the organization of the action group dissemination plan. Eighteen youth gathered firewood from the new school site and delivered it to elders throughout the community. This activity contributed to youth empowerment in the research process by reinforcing and affirming what youth had told us, as researchers, about what was important to them. This action group activity resonated with young community members as a learning experience about themselves and a tangible outcome from research; it was talked about widely in the community and brought up by community members to the university researchers during consecutive trips to the community.

The second youth action group activity, being proud of our village, also came out of the local analysis of the interview data. Youth in the project talked about the importance of being connected to the community and having pride in the community. The presence of graffiti and trash around the community was cited as a source of stress for some of the youth in the project. Two of the authors (Ford & Rasmus) worked with the Traditional Council in the community and with several of the youth co-partners to put together a youth action dissemination activity to cover the graffiti on the Traditional Council building. LSC members and youth researchers were instrumental in announcing and recruiting for the action group. After the graffiti was painted over, 29 youth and adults gathered for refreshments in the Tribal Council building to hear from Elders and adults about traditional Yup'ik cultural perspectives on the power of using positive words. Youth were praised by the elders of the community for their involvement in removing the negative graffiti messages and for enhancing pride in their community. The action group resulted in increased youth participation in promoting the health of their community. The youth that were involved took more ownership of their surroundings in the community that they themselves identified as stressful and/or problematic. Many of the youth wanted to keep the activity going and paint over other graffiti still present in places around the village. The development of this action group dissemination activity was an iterative process involving community engagement, return to interview data, and then return to community engagement. Maintaining local youth perspectives was essential for continued youth involvement throughout the research process.

Discussion

Strategies to foster indigenous youth involvement in meaningful ways can enhance both the science and the impact of health related research with youth. Youth involvement in circumpolar health research about youth is a topic deserving of far greater attention. It remains an important question whether CBPR about youth can truly be CBPR without the active involvement of youth in all aspects of the research process. The three strategies implemented in this study provide ways for increasing youth involvement in health research. This paper highlights activities in the dissemination phase of the research process with an action component that created opportunities for youth to reflexively experience activities that from the perspectives of their peers were important to well-being and healthy living. These activities approached dissemination of research findings by providing tangible, hands on experiential learning opportunities about the research findings in ways that gave back to the community.

This study illustrates the benefits of a youth involved CBPR process that includes obtaining research input from the LSC, employing youth co-researchers in multiple stages of the research process, implementing youth-action translation groups, and collaboratively transforming research findings into action dissemination activities. Along with the benefits come challenges; a primary challenge in CBPR is building and maintaining trust (41). We believe this is particularly true for indigenous and circumpolar settings (42). Establishing trust was especially important when working with young community members. Adults in the community were initially cautious of the research project. Likewise, youth were hesitant to engage in the research process until trust in the researchers was established. The combination of previous work in the community (38,43) and continued transparency with community members and youth participants facilitated trust between researchers and the community.

Another challenge in youth driven CBPR, especially in the tight knit context of small, remote circumpolar indigenous communities, is protection of participants’ confidentiality and anonymity. Researchers worked closely with the university institutional review board to ensure ethical means were employed for youth-action groups and sharing emergent findings with the LSC. De-identifying data to be shared with the LSC was particularly challenging. In several cases, the de-identification of the key data for understanding was just not possible. In these cases, researchers consulted with participants. Youth participants approved data to be shared with their parents, who then gave consent to disclose data with the wider community. Sharing these quotes with parents was another impactful way of communicating results; parents hearing examples of their child engaged in thoughtful reflections had an observed positive impact on community perceptions of the research and of community youth. These steps fostered trust, increased research interest, and maintained youth involvement in the research process.

The more accessible the research process was to youth, the more youth became involved in the process. This included everything from where we met physically, to how we presented information, and how we did dissemination through the action groups. Wong et al's. (26) empowerment framework suggests a continuum for youth participation in the research process. We believe part of this continuum, for indigenous youth, must include culturally appropriate mechanisms for their involvement. For example, when elders and adults are part of a meeting, the youth role is to listen and absorb shared information. Having youth-action groups offered a forum for youth to express their thoughts. Research informing youth public health programming and interventions can benefit from these CBPR strategies for promoting indigenous youth involvement in the research process. The innovation of action dissemination groups provided an opportunity for youth community members to experientially learn and understand research findings in a dynamic, health promoting, capacity building light. Through a youth-guided CBPR process, this project was able to capture the interest of youth in the community, and give back to the community by getting the youth involved in meaningful ways that contributed to the collective health and wellbeing of the membership.

Implementation of a three-tiered approach of CBPR process involving the LSC, youth-researcher partnerships, and youth action groups led to increased youth involvement in the research process. The LSC, youth-researcher partners, and youth action groups were together vital to the enhancement of youth involvement in the research process. The LSC evolved to include significant youth involvement in the CBPR process. In particular, dissemination of findings, shaped by the contextual perspectives of youth, was transformed to action through collaborative efforts with youth. This process resulted in action groups made up of the young members of the community. Project updates to local institutions actively involved in efforts to enhance the health of young community members, such as the Tribal Council, regional health corporation health providers, and school personnel, facilitated heath impacts of the project and provided supports for youth involvement. These CBPR strategies supported youth involvement with important implications for research leading to health and public health programming and interventions. The strategies served to further increase youth involvement in the research project and involve them in a deeper understanding of the research findings. Youth involvement also improved the science; youth involvement informed life history interview methods and increased the numbers of community youth interested in participation in the project. These strategies additionally point to promising mechanisms by which to involve youth in youth health intervention activities.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the youth that participated in this research project, for they willingly opened their life stories up to us. It is our aim to respect and preserve their voice in our work. Next, we would like to acknowledge the tireless youth researcher partners and local steering committee members, which provided guidance, input, support, and direction in our aim to facilitate a collaborative project. We would like to thank the community including the school, tribe, city, cooperation, and parents. The combined group is passionate about the wellbeing and health of the youth in their community. The Yup'ik local steering committee (LSC) is Lawrence Edmund, Paula Ayunerak, Hilda Stern, Marlene Ayunerak, Josie Edmund, Felicia Nicholi, Katrina Patrick, James Isidore and Freddie Edmund. The Circumpolar Indigenous Pathways to Adulthood cross-site research team is James Allen, Stacy Rasmus, Lisa Wexler, Michael Kral, Olga Ulturgasheva, Tara Ford, Janet Mazziotti, Kim Hopper, and Kristine Nystad. This research was funded by the National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs ARC-00756211 and ARC-00756211 Amendment 001 and 002, and the National Center for Research Resources [P20RR061430].

Conflict of interest and funding

Researchers involved in the CIPA project have no financial or personal relationships with other individuals or organizations that could influence the results or interpretation of the study.

References

- 1.Gilman A, McAllister K, Wigle D, Gibbons T, Moyston-Cumming M, van Oostdam J. Health and environmental indicators for children and youth in the circumpolar arctic. Epidemiology. 2005;16:S144–S5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehti V, Niemels S, Hoven C, Mandell D, Sourander A. Mental health, substance use and suicidal behaviour among young indigenous people in the Arctic: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:1194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacMillan HL, Jamieson E, Walsh C, Boyle M, Crawford A, MacMillan A. The health of Canada's Aboriginal children: results from the First Nations and Inuit Regional Health Survey. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2010;69:158–67. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v69i2.17439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen J, Levintova M, Mohatt G. Suicide and alcohol related disorders in the US Arctic: boosting research to address a primary determinant of circumpolar health disparities. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2011;70:473–87. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v70i5.17847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Einarsson N, Larsen JN, Nilsson A, Young OR, editors. Arctic Human Development Report (AHDR) Akureyri: Stefansson Arctic Institute; 2004. pp. 15–118. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poppel B, Kruse J, Duhaime G, Abryutina L. SLiCA Results; Anchorage: Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska Anchorage; 2007. http://www.arcticlivingconditions.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjerregaard P. Rapid socio-cultural change and health in the Arctic. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2001;60:102–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turi AL, Bals M, Skre IB, Kvernmo S. Health service use in indigenous Sami and non-indigenous youth in North Norway: a population based survey. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:378. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wexler L, Hill R, Bertone-Johnson E, Fenaughty A. Correlates of Alaska Native fatal and non-fatal suicidal behaviors 1990–2001. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38:311–20. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kvernmo S, Heyerdahl S. Acculturation strategies and ethnic identity as predictors of behavior problems in arctic minority adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:57–65. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Neil JD. Colonial stress in the Canadian Arctic: an ethnography of young adults changing. In: Janes CR, Stall R, Gifford SM, editors. Anthropology and epidemiology: interdisciplinary approach to the study of health and disease. Dordrecht: Reidel Publishing Co; 1986. pp. 249–74. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wexler L. Identifying colonial discourses in Inupiat young people's narratives as a way to understand the no future of Inupiat youth suicide. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2009;16:1–24. doi: 10.5820/aian.1601.2009.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wexler LM. Inupiat youth suicide and culture loss: changing community conversations for prevention. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2938–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kral MJ, Idlout L. Community wellness and social action in the Canadian Arctic: collective agency as subjective well-being. In: Kirmayer LJ, Valaskakis GG, editors. Healing traditions: the mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press; 2009. pp. 315–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wexler L. The importance of identity, culture and history in the study of indigenous youth wellness. J Hist Childhood Youth. 2009;2:267–78. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wexler L, DiFluvio G, Burke T. Resilience in response to discrimination and hardship: considering the intersection of personal and collective meaning-making for Indigenous and GLBT youth. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:565–70. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walters KL, Stately A, Evans-Campbell T, Simoni JM, Duran B, Shultz K, et al. “Indigenist” collaborative research efforts in Native American communities. In: Stiffman AR, editor. The field research survival guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 146–73. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Prom Prac. 2006;7:312–23. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holkup PA, Tripp-Reimer T, Salois EM, Weinert C. Community-based participatory research an approach to intervention research with a Native American community. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2004;27:162–75. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Satcher D. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Franscisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. p. 524. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM, Thomas LR, Hazel K, Allen J, Hensel C. “Tied Together like a Woven Hat:” protective pathways to sobriety for Alaska Natives. Harm Reduction J. 2004;1:10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas LR, Donovan DM, Sigo RL, Austin L, Marlatt GA. The community pulling together: a tribal communityuniversity partnership project to reduce substance abuse and promote good health in a reservation tribal community. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2009;8:283–300. doi: 10.1080/15332640903110476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flicker S. Who benefits from community-based participatory research? A case study of the positive youth project. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35:70–86. doi: 10.1177/1090198105285927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schensul JJ, Berg MJ, Schensul D, Sydlo S. Core elements of participatory action research for educational empowerment and risk prevention with urban youth. Practicing Anthropology. 2004;26:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuck E. Re-visioning action: participatory action research and indigenous theories of change. Urban Rev. 2009;41:47–65. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong NT, Zimmerman MA, Park EA. A typology of youth participation and empowerment for child and adolescent health promotion. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;46:100–14. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gådin KG, Weiner G, Ahlgren C. Young students as participants in school health promotion: an intervention study in a Swedish elementary school. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009;68:498–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perry C, Hoffman B. Assessing tribal youth physical activity and programming using a community-based participatory research approach. Public Health Nurs. 2010;27:104–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teufel-Shone NI, Siyuja T, Watahomigie HJ, Irwin S. Community-based participatory research: conducting a formative assessment of factors that influence youth wellness in the Hualapai community. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1623–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz JR, Martinez T, Paul R. Community-based participatory research and American Indian/Alaska Native nurse practitioners: A partnership to promote adolescent health. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23:298–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2011.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Draper AK, Hewitt G, Rifkin S. Chasing the dragon: developing indicators for the assessment of community participation in health programmes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephens C. Community as practice: social representations of community and their implications for health promotion. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2007;17:103–14. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shagi C, Vallely A, Kasindi S, Chiduo B, Desmond N, Soteli S, et al. A model for community representation and participation in HIV prevention trials among women who engage in transactional sex in Africa. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1039–49. doi: 10.1080/09540120701842803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hart R. Children's participation: from tokenism to citizenship (no. 4) Florence: UNICEF International Child Development Centre; 1992. pp. 5–37. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foster-Fishman P, Nowell B, Deacon Z, Nievar MA, McCann P. Using methods that matter: the impact of reflection, dialogue, and voice. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;36:275–91. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8626-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohatt GV, Hazel KL, Allen J, Stachelrodt M, Hensel C, Fath R. Unheard Alaska: culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;33:263–73. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027011.12346.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM, Thomas L, Allen J, Hazel K, Marlatt GA. Risk, resilience, and natural recovery: a model of recovery from alcohol abuse for Alaska Natives. Addiction. 2008;103:205–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen J, Mohatt G, Fok CC, Henry D. People awakening team. Suicide prevention as a community development process: understanding circumpolar youth suicide prevention through community level outcomes. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009;68:274–91. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v68i3.18328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jolles C. Faith, food & family in a Yup'ik whaling community. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 2002. pp. 93–201. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fienup-Riordan A, editor. Quilrat qanemcit-llu kinguvarciamalriitStories for future generations: the oratory of Yup'ik Eskimo elder Paul John. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 2003. pp. 3–475. Bethel, Calista Elders Council. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AK, Young S. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1398–406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen J, Mohatt GV, Markstrom CA, Byers L, Novins DK. “Oh no, we are just getting to know you”: The relationship in research with children and youth in indigenous communities. Child Dev Perspect. 2012;6:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen J, Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM, Two Dogs R, Ford T, Iron Cloud Two Dogs E et al. Cultural interventions for American Indian and Alaska Native youth: the Elluam Tungiinun and Nagi Kicopi programs. In: Spicer S, Farrell M, Sarche S, Fitzgerald HE, editors. Child psychology and mental health: cultural and ethno-racial perspectives, American Indian child psychology and Mental Health, Vol. 2: prevention and treatment. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC; 2011. pp. 337–64. [Google Scholar]