Abstract

The present study aimed to develop a method of quantification of heat shock protein transcript levels in the estuarine copepod Eurytemora affinis. For that, the full-length cDNA of the 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (Ea-grp78) and the cytosolic 90-kDa heat shock protein (Ea-hsp90A) from this species have been cloned. These cDNA revealed, respectively, 2,370 and 2,299 bp with 1,971 and 2,124 bp open reading frames encoding 656 and 707 amino acids. Main features, sequence identities and phylogenetic analysis with other species were described. Then, the expression profiles were analysed using reverse transcription/real-time quantitative PCR method from copepods subjected to different thermic and osmotic stresses in laboratory, and from copepods directly sampled into the natural population of the Seine Estuary (France) along a salinity gradient. Thermic shock (7.5°C, 22.5°C and 30°C during 90 min) significantly induced increases of transcript quantities ranged between 1.7- and 19.7-fold the levels observed in control conditions (15°C). Hypo- and hyper-osmotic shocks (salinities of 1 and 30 during 90 min) caused a 2-fold induction of Ea-hsp90A transcript level in comparison to controls (salinity of 15) whereas no significant change was measured for Ea-grp78. On the other hand, similar expression profiles were observed for the two transcripts after 72 h of exposition to salinities of 1 and 25 with a significant 2-fold induction observed for the lower salinity. To finish, strong expression inductions of both Ea-grp78 and Ea-hsp90A genes were observed in field copepods sampled at low salinity during the campaigns of June 2009 and May 2010. These results tend to show that the low salinity and the increase of temperature seem to have a synergic effect on stress condition of copepods.

Keywords: Abiotic stress, Copepod, Estuary, Glucose-regulated protein 78, Heat shock protein 90

Introduction

The capacity to cope with the insults of environmental physical and chemical fluctuations is an essential process, which directly impacts the biogeographical distribution and interaction of aquatic species. Nowadays, the understanding of variations of physiological traits over large spatial scales and the ecological significance of the observed variations are emerging as central questions in ecological physiology (Hofmann 2005). Under stress conditions, cellular functions and homeostasis are maintained through highly conserved cellular defence mechanisms. One of the most characterized stress responses is the induction of an evolutionally conserved set of polypeptides termed heat shock proteins (HSPs).

HSPs are a large group of molecular chaperones that are found from prokaryotes to vertebrates and higher plants. HSPs play an important role in transport, folding, unfolding, assembly and disassembly of multi-structured units and degradation of misfolded or aggregated proteins (Mayer and Bukau 2005 for review). These tasks are fundamental in many normal cellular processes; however, the need for molecular chaperones is accelerated under stressful conditions that could potentially damage cellular and molecular structures in cells. HSPs synthesis has been shown to be up-regulated in response to a wide variety of environmental insults such as thermal stresses, osmotic stresses, anoxia, ultraviolet light irradiation, exposure to inorganic and organic contaminants, as well as infection by pathogens (Mouneyrac and Roméo 2011; Sørensen et al. 2003 for review). Thus, HSPs are important for recovery and survival of organisms (Lindquist 1986). More globally, it has been suggested that HSPs can play an important role in the ecology and evolution of populations, notably for organisms inhabiting variable environments, making them interesting biomarkers of stress for ecological physiology approaches (Sørensen et al. 2003).

HSP70s and HSP90s are considered as the major chaperones and constitute the most studied HSP families in eukaryotes. In most of eukaryotic cells, three forms of HSP70s as well as HSP90s exist with different functions and intracellular locations, i.e. mitochondrial or chloroplast organelles, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen and cytoplasm (Chen et al. 2005a; Karlin and Brocchieri 1998). The mitochondrial and chloroplastic forms of HSP70s and HSP90s are more closely related to their respective prokaryotic counterparts, DnaK and Htpg, than the others eukaryotic forms. GRP78 (78-kDa glucose-regulated protein, also referred to immunoglobulin binding protein BiP) and GRP94 (94-kDa glucose-regulated protein, also referred to HSP90B) are the ER paralogs of HSP70 and HSP90, respectively. GRP78 is evolutionary conserved from yeast to humans, whereas GRP94 has only been identified in vertebrates (Lee 2001 for review). GRPs play notably a key role in the unfolded protein response (UPR): an adaptive process which takes place in response to ER homeostasis disruptions such as accumulation of misfolded proteins, Ca2+ depletion or oxidative stress. The cytosolic forms can be divided into the constitutive and inducible subgroups. Then, in large part of eukaryotic organisms, the heat shock cognate (HSC) proteins 70 that are expressed constitutively and are involved in normal cellular processes can be distinguished from the inducible HSP70, which are produced under stress conditions. In vertebrates, two cytosolic forms of HSP90, HSP90AA (inducible form) and HSP90AB (constitutive form), equally exist and are likely to result from a gene duplication which occurred approximately 500 million years ago (Chen et al. 2005a).

Estuarine aquatic wildlife and particularly zooplanktonic community appears as an interesting model system to investigate the role of physiological processes such as the HSP synthesis on the ecology of species. Indeed, estuaries are complex ecosystems, which are subjected to marked physicochemical small-scale changes (mainly salinity, turbidity and current flow) associated with tidal cycles and to large-scale seasonal variations (essentially temperature). Capacity of aquatic organisms to tolerate those environmental variations determines their spatio-temporal repartition along the estuarine gradient and their capacity to survive and to overlap low tolerant-species in such a stressful environment (Laprise and Dodson 1994). The calanoid copepod Eurytemora affinis is known to have physiological capacities to invade freshwater environment through the saline gradient of estuaries (Lee 1999; Lee and Peterson 2003). As a result, this species is distributed in a large spectrum of habitats characterized by large range of salinity, from hyperhaline salt marches to lakes and is one of the most common copepods of the northern hemisphere estuaries (Lee 1999). In the Seine Estuary (France), E. affinis dominates the zooplankton community during most of the year in the oligohaline and mesohaline zones (salinity from 2.5 to 18) and can frequently be found in the polyhaline zone (salinity from 18 to 30; Devreker et al. 2008; Mouny and Dauvin 2002). E. affinis plays a key role in the food web of the low salinity zone of the Seine Estuary by being one of the principal consumers of phytoplankton and detritus and the most abundant prey for mysids, shrimp and fish (Dauvin and Desroy 2005). Due to its ecological interest, several works have investigated the effects of environmental factors on E. affinis life traits, its geographical distribution and/or its interactions with others species (Beyrend-Dur et al. 2009; Devreker et al. 2009; Kimmel et al. 2006 for example). However, much less is known about physiological events occurring at lower biological levels. Only some studies reported the influence of temperature and osmotic stress on pattern of total protein and/or HSP expression in this species (e.g. Gonzalez and Bradley 1994; Hakimzadeh and Bradley 1990; Kimmel and Bradley 2001). Although traditional methods of protein expression analysis employed in these studies are relevant approaches to elucidate the mechanism of HSP regulation and expression, they rarely allow discriminating the different forms of HSP (ER, cytosolic, inducible or constitutive) and they generally require an important quantity of organisms. An alternative and complementary approach is the use of transcriptomic methods based on the detection of mRNA. These methods, which benefit from the specificity and sensitivity of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based procedures, make it possible to investigate the role of genes coding for HSPs in greater details. In addition, very little sample material is needed, making the study of small organisms such micro-crustaceans easier. However, these methods require that the complementary DNA (cDNA) of interest genes have been cloned. To date, the cDNA of HSP70 and HSP90 forms have been cloned from only one copepod species i.e. the marine harpacticoid Tigriopus japonicus (Rhee et al. 2009). More generally, as underlined by Luan et al. (2010), few reports exist on crustacean species.

In this context, the quantification of hsp gene expression in estuarine copepod species such as E. affinis presents a real interest for ecological physiology practices at large spatial scales and could contribute to better understand the role of HSPs for ecology and evolution of these cryptic populations. The present study is a first step, which aims to develop a method of quantification of hsp gene expression in E. affinis with a view to future applications in ecological physiology. The investigation was focused on forms of HSP90 and HSP70 families. We implement here the data on stress proteins in copepods: (1) the cDNA sequences encoding grp78 and hsp90A transcripts in E. affinis were cloned and characterized (designed Ea-grp78 and Ea-hsp90), (2) their expression pattern were analysed by reverse transcription/real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) from copepods subjected to different thermic and osmotic stresses in laboratory and (3) from copepods directly sampled into the natural population of the Seine Estuary along a salinity gradient.

Materials and methods

E. affinis sampling and culture

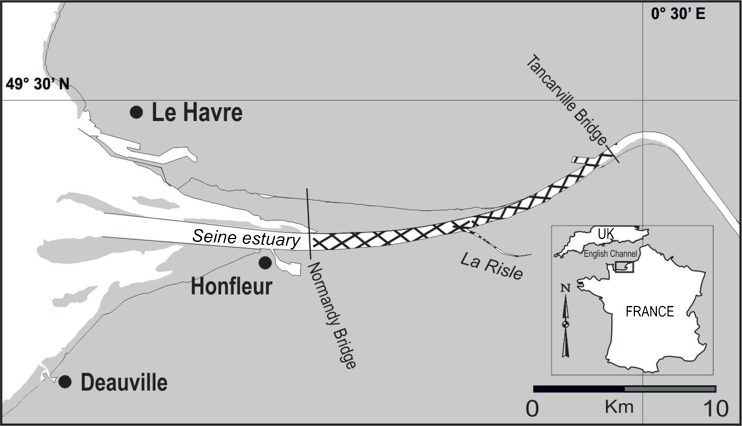

Several sampling were conducted in the Seine Estuary (Haute-Normandie, France) from 2009 to 2010. E. affinis individuals were collected along salinity gradient in the estuarine turbidity maximum zone using horizontal plankton net (200 μm mesh size) from the RV Côtes de la Manche (Fig. 1). The field salinity and temperature conditions of different sampling are detailed in Table 1. Immediately after sampling, a fraction of copepods was directly conditioned for RT-qPCR applications; the rest was transferred into containers filled with filtered estuarine water and brought back to be cultured in perspectives of laboratory experiments (see the “Analysis of expression patterns: effect of water temperature and salinity, and preliminary field approach” section). In the last case, culture was performed on the basis of procedure described in Devreker et al. (2009). Copepods were reared in 40-L aquariums filled with artificial brackish water at salinity 15 (a mixture of UV-treated filtered (1 μm) sea water and deionised water) under constant aeration. Photoperiod and temperature were maintained at 12:12 h light/dark and 15 ± 1°C, respectively. Copepods were fed every 2 days with a mixture of Rhodomonas marina (15 μm diameter) and Isochrysis galbana (4.5 μm diameter) at a ratio of 2:1 (cell/cell) for a total of approximately 20,000 cells·mL−1. Algae cultures were grown at 20°C in 10 L tanks under 24 h fluorescent illuminations in Conway medium. Water was renewed every 3 weeks. Animals were kept in these conditions during an acclimation period of at least 3 weeks before use for experiments.

Fig. 1.

Map of the sampling location in the lower part of the Seine Estuary. Sampling zone is hatched and the black points indicate the principal cities

Table 1.

Values of water salinity and temperature (in °C) recorded along the salinity gradient of the Seine estuary during the sampling campaigns in April and June 2009 and May 2010, and corresponding levels of Ea-hsp90A and Ea-grp78 transcripts measured in pools of 50 adult E. affinis

| Sampling date | Water characteristics | Transcript levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salinity | Temperature | Ea-hsp90A | Ea-grp78 | |

| April 29, 2009 | 4.2 | 15.4 | 243,995 ± 76,075a | 6,523 ± 1,881a |

| 9.9 | 15.3 | 326,155 ± 139,085a,b | 11,768 ± 4,974a,b | |

| 14.5 | 14.3 | 382,700 ± 110,438a,b | 13,589 ± 5,211a,b | |

| 20.2 | 13.6 | 329,344 ± 107,832a,b | 15,607 ± 6,323a,b | |

| June 27, 2009 | 0.5 | 20.0 | 942,658 ± 232,941b | 50,608 ± 18,380b |

| May 31, 2010 | 4.8 | 16.6 | 890,069 ± 443,966b | 61,569 ± 34,746b |

| 10.0 | 16.3 | 606,775 ± 166,061b | 28,620 ± 5,519a,b | |

| 14.1 | 15.9 | 591,328 ± 295,756a,b | 11,802 ± 6,468a,b | |

Data of transcript level are reported as mean ± standard deviation of cDNA copy number (n = 5). Similar letters indicate no significant difference (p > 0.05)

Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Samples were grinded using micro-pestles (Eppendorf, Lelec, France), during 3 freeze/thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen, and then homogenized in 250 μL of nuclease-free ultra-pure water (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France). Total RNAs were extracted using Tri-Reagent LS (Euromedex, Mundolsheim, France) according to the method described in Xuereb et al. (2011). To remove any potential contamination with genomic DNA, RNA were digested and purified with TURBO DNA-free® kit (Ambion Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations and purity were measured using a NanoDrop® ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Tehnologies, ThermoScientific, Wilmington, USA), and sample integrity was evaluated after RNA migration in a 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, before storage at −80°C. Samples exhibited no RNA fragmentation and had 260:280 nm ratios upper than 1.8. Messenger RNA (mRNA) contained in 1 μg of total RNA were reverse transcribed to complementary first-strand DNA (cDNA) with M-MLV reverse transcriptase Rnase H minus (Promega, Charbonnières, France) using oligo(dT)20 in presence of Recombinant RNasin® Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Promega) according to the method described in Xuereb et al. (2011). Finally, cDNAs (40 μL) were diluted in 60 μL of ultra-pure water and stored in 5 μL aliquots at −20°C.

cDNA cloning and characterization

Degenerate primers (DP) were designed from hsp70 and hsp90 cDNA sequences available on the GenBank database by using Primer 3 v.0.4.0 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/; Table 2). PCR was performed using DyNAzymeTM II PCR master mix (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) under the following conditions: 95°C/4 min; 45 cycles of 95°C/30 s, 50°C or 55°C/45 s, 72°C/1 min; and 72°C/5 min. The amplified PCR products were isolated from 1.2% agarose gel, cloned into pGEM®-T Vector System (Promega) and transformed into competent Escherichia coli cells XL1-Blue (Stratagene, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Sequencing was performed by the MilleGen® company (Labège, France) with ABI3130XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems) by using BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). Membership of the PCR products to the hsp70 and hsp90 gene families was verified by Blast analysis (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Table 2.

Primers used for degenerate and RACE PCRs

| Step | Oligo name | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Degenerate PCR | DP-hsp70.F | CTTAYGGGTTSGACAAGAA |

| DP-hsp70.R | ATCTTGGGGATRCGRGTGG | |

| DP-hsp90.F | GAGACCTTYGCVTTYCAGG | |

| DP-hsp90.R | GTTDCCCACYCCRAAYTGNCC | |

| RACE | GSP-hsp70.3′F | GTACCTTTGATGTCTCTCTGCTCACC |

| GSP-hsp70.5′R | CGGGCTTCAGGGTTCCACGGAACAGGTCCA | |

| GSP-hsp90.3′F | CGCGTTCCAGGCCGAGATTGCACAGCTT | |

| GSP-hsp90.5′R | ACTAATATCAGCTCCGGCCTGAAGAG | |

| AP | CCATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC |

AP adaptor primer, DP degenerated primer, GSP gene specific primer

The full-length cDNA of E. affinis hsp70 and hsp90 were obtained by RACE PCR using MarathonTM cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech, Saint Germain en Laye, France) according to the user’s manual. The 5′- and 3′-RACE products were amplified by PCR using gene-specific primers (GSP) specially designed and Adaptor Primer (AP) supplied with the RACE PCR Kit (Table 2). The PCR cycling parameters were as follows: 94°C/30 s; 5 cycles of 94°C/15 s, 62°C/1 min and 72°C/3 min; 5 cycles of 94°C/15 s, 62°C/1 min and 70°C/3 min; 25 cycles of 94°C/15 s, 62°C/1 min and 68°C/3 min; and 72°C/10 min. The final PCR products were both isolated from agarose gel and sequenced, as described above, by the MilleGen® company. The sequences obtained after 5′- and 3′-RACE were assembled using Geneious ProTM v5.3 software.

The structural analysis of full-length cDNA sequences was performed using online softwares. The open reading frames (ORF) of the cDNA were determined using ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gorf/). Theoretical protein molecular mass and isoelectric points were predicted using compute pI/Mw tool (http://expasy.org/tools/pi_tool.html). The putative signal peptide was researched using SignalP (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP). Scans for known amino acid motifs were performed against Prosite and Pfam database (http://myhits.isb-sib.ch/cgi-bin/motif_scan).

The phylogenetic analysis was performed after global alignment of amino acid E. affinis sequences with counterparts from 35 and 8 crustacean species for GRP78 and HSP90, respectively. All sequences were collected from the GenBank database. The tree was constructed by Jukes–Cantor genetic distance model and neighbour-joining method using Geneious v5.4 software (Drummond et al. 2011). Blosum62 was used as the cost matrix. The gap open and gap extension penalties were 12 and 3, respectively. HSP70 and HSP90 trees were respectively rooted using Vibrio proteolyticus DNAK and Mytilus galloprovincialis HSP90 as outgroups. The analysis of HSP amino acid conservation was conducted comparing percent identities generated from pairwise alignments (EMBOSS, European Bioinformatics Institute).

Analysis of expression patterns: effect of water temperature and salinity, and preliminary field approach

Laboratory experiments

The effects of temperature and salinity on the expression of characterized hsp genes were individually assessed under controlled laboratory conditions. During a first experiment, copepods were exposed to thermic or osmotic shocks during 90 min. Adult copepods of mixed gender (n = 300 per replicate) were placed into 50-mL plastic tubes (n = 3) for each tested conditions (control and treatments). The control copepods were maintained in optimal temperature (15°C) and salinity (15) conditions (Devreker et al. 2007; 2009). Three thermic shocks (7.5°C, 22.5°C and 30°C at the optimum salinity) and 2 osmotic shocks (salinities of 1 and 30, at the optimum temperature) were tested. In a second experiment, copepods were exposed during 72 h in 3 different salinities (1, 15 and 25), at the optimal temperature condition, in 40-L aquariums. This experiment was performed under the same light and aeration conditions as in the main culture (see the “E. affinis sampling and culture” section). At the end of exposure, for both experiments, copepod pools of about 250 adults (n = 3 per condition) were recovered by sieving (200 μm mesh size), quickly rinsed with ultra-pure water and placed in sterile microtubes before freezing in liquid nitrogen and storage at −80°C until RNA extraction (see the “Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis” section).

Field experiment

The spatio-temporal variability of the studied hsp gene expression was assessed within the natural E. affinis population of the Seine Estuary. Copepods were sampled along the salinity gradient on April 29 and June 27, 2009 and May 27, 2010 (Fig. 1; Table 1) as described in the “E. affinis sampling and culture” section. It can be underlined that copepods were found only at the salinity of 0.5 in June 2009 and no copepods were found at salinities upper to 14.1 in May 2010. Immediately after sampling, pools of 50 copepods (n = 5 per sampling point) were constituted by gentle pipetting to maximise the specific selection of adult E. affinis (males and females in sexual rest), placed in microtubes and quickly rinsed in ultra-pure water before freezing in liquid nitrogen. At the laboratory, samples were stored at −80°C until RNA extraction (see the “Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis” section).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

The specific primer sets used for qPCR (Table 3) were designed using the “Universal Probe Library” software (Roche Diagnostics). qPCR was carried out in duplicate on the Rotor-Gene Q 2-plex HRM (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) using the QuantiTect® SYBR® Green PCR Kit (Qiagen), in 20-μL volume containing 5 μL of cDNA sample, 4 μL of ultra-pure water, 1 μL of primers (forward and reverse; 10 μM) and 10 μL of QuantiTect Master Mix 2X. Blank controls were performed for each qPCR run to check the absence of contamination by DNA in reagents. After initial denaturation at 95°C/15 min, cDNA were amplified for 45 cycles of 94°C/15 s, 59°C/20 s and 72°C/15 s. Following the last PCR cycle, all cDNA were denatured by a rapid increase to 95°C and hybridized again for 20 s at 68°C. The melting curve was finally determined during a slow temperature elevation from 55°C to 99°C (0.2°C s−1). The specificity of PCR products was checked by melting curve analysis and by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The expression levels of target genes were calculated according to the absolute quantification method (Chen et al. 2005b; Nadam et al. 2007; Wong and Medrano 2005). The values of quantification cycle (Cq; cycle number from which fluorescence is detected above the noise threshold) were collected with Rotor-Gene Q series software (Qiagen) using the comparative quantification method. To convert Cq values into cDNA copy number quantified from 5 μL-aliquot of RT product, a specific standard curve was established for each primer pair from 10-fold serial dilutions of purified PCR products (from 109 to 101 cDNA copies; in triplicate). For that, a cDNA sample was amplified with HotStar HiFidelity DNA Polymerase (Qiagen) according to the user’s manual and purified with QIAquick PCR® Purification Kit (Qiagen). cDNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop® ND-1000 Spectrophotometer and dilution series were performed in ultra-pure water. A dilution of medium range (corresponding to 105 cDNA copies), defined as standard points, was distributed in 5-μL aliquots and stored at −20°C. This standard point was systematically amplified during the qPCR runs to confirm the reliability of amplification reading and to correct Y-intercept of standard curve equation. The equation and R2 of standard curve, and PCR efficiency (E = 10^(−1/slope)) of each target genes are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Primers used for qPCR

| Oligo name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Amplicon size | Standard curve | PCR efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR-grp78.F | AAGCCCGTCCAGAAGGTT | 71 nt | y = −4.0274x + 43.546 | 1.771 |

| qPCR-grp78.R | CCAACAAGAACAATCTCGTCAA | R2 = 0.999 | ||

| qPCR-hsp90A.F | AGATATGAATCCCTCACTGATGC | 68 nt | y = −4.0119x + 43.187 | 1.775 |

| qPCR-hsp90A.R | GGGATGAGTTTGATGTACAGACC | R2 = 0.999 |

Statistics

Statistical procedures were carried out with the Statistica software v7 (Statsoft). Considering small sample size, only non-parametric analyses are reported here. For the laboratory experiments, we focused on the differences between the control (i.e. optimal condition) and each treatment condition. Concerning thermic treatments, the global differences were tested using non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA rank sum tests (p < 0.05), then two-sample comparisons were performed using Unilateral Mann–Whitney rank sum tests (p < 0.05). For salinity treatments, control condition was compared to only two “extreme” treatments. So statistical analysis focused on the two-sample comparisons were performed using Unilateral Mann–Whitney rank sum tests (p < 0.05). Concerning the field experiment, inter-group differences were assessed using non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA and multile comparison rank sum tests (p < 0.05).

Results

Identification and analysis of full-length cDNA sequences

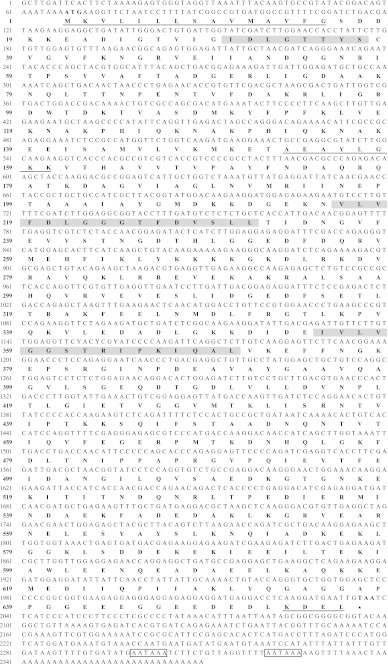

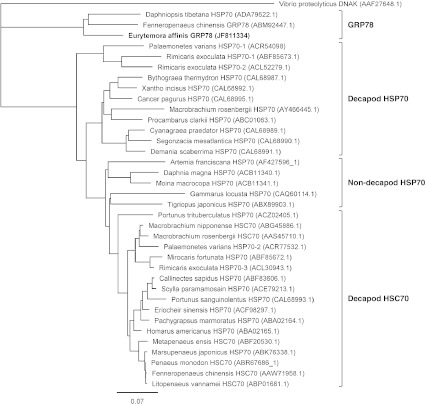

Degenerate primer pair DP-hsp70.F/DP-hsp70.R generated a fragment of 473 bp. Blast analysis confirmed that the fragment was a part of a hsp70 gene sequence. The 2,370 bp full-length cDNA sequence was secondary obtained by 5′- and 3′-RACE PCR (GenBank accession number, JF811334). It contained a 1,971-pb ORF encoding a 656-amino acid polypeptide, a 5′-terminal untranslated region (UTR) of 67 bp, and a 3′-UTR of 332 bp including a stop codon (TAA), two signal sequences for polyadenylation (AATAAA) and a poly(A) tail (Fig. 2). The deduced amino acid sequence has a calculated molecular mass of 72.04 kDa and a theoretical isoelectric point of 4.89. The possibility of false prokaryotic cloning was excluded since the consensus motif “GPKH” identified by Karlin and Brocchieri (1998) among all prokaryote and mitochondrial HSP70 sequences, is absent in the sequence. The Signal P software detected a signal peptide of 15 amino acids (MKVLILLSAVMAVFG). Motif scan analysis showed that the predicted amino acid sequence displays all three conserved HSP70 protein family signatures, [IV]-DLGT-[ST]-x-[SC] (residues 30–37; Prosite ID HSP70_1 PS00297), [LIVMF]-[LIVMFY]-[DN]-[LIVMFS]-G-[GSH]-[GS]-[AST]-x(3)-[ST]-[LIVM]-[LIVMFC] (residues 216–231; Prosite ID HSP70_2 PS00329), and ([LIVMY]-x-[LIVMF]-x-GG-x-[ST]- [LS]-[LIVM]-P-x-[LIVM]-x-[DEQKRSTA] (residues 355-370; Prosite ID HSP70_3 PS01036). A motif very similar to ATP/GTP-binding site motif A (P-loop; prosite ID ATP_GTP_A PS00017), AEAYLGKK, is located at amino acid residues 153–160. The C-terminal consensus ER signature, [KH]-DEL, is present at position 653–656. Phylogenetic analysis of crustacean HSP70 sequences is presented in Fig. 3. Two groups of sequences are clearly bringing to light by high phylogenetic distance. The most represented group corresponds to the cytosolic form of HSP70. It could be subdivided into three sub-groups: the decapod inducible form (identified as Decapod HSP70), the decapod constitutively expressed form (identified as Decapod HSC70) and the non-decapod sequences (identified as Non-decapod HSP70). The second group, including E. affinis sequence, would correspond to the ER form of HSP70 (i.e. GRP78), since all sequences contained a signal peptide and the C-terminal consensus ER signature (i.e. KDEL). In agreement, pairwise alignment analysis indicated that HSP70 sequence characterized in E. affinis shares high identities with GRP78 amino acid sequences of the crustaceans Daphniopsis tibetana (85.37%; ADA79522.1) and Fenneropenaeus chinensis (83.74%; ABM92447.1), the insect Drosophila melanogaster (83.79%; NP_727563.1), the vertebrates Mus musculus (82.36%; NP_071705.3), Gallus gallus (82.06%; NP_990822.1), Danio rerio (81.62%; NP_998223.1) and Xenopus tropicalis (81.55%), the mollusc Crassostrea gigas (79.75%; BAD15288.1) and the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (77.78%; AAA28074.1). Conversely, the identity percentage with cytosolic HSP70 amino acid sequences of others crustaceans species only ranged from 60.16 (Rimicaris exoculata HSP70-1; ABF95673.1) to 63.32 (Portunus sanguinolentus HSP70; CAL68993.1). Consequently, HSP70 sequence characterized in E. affinis in this present work has been designed as Ea-GRP78.

Fig. 2.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of GRP78 from Eurytemora affinis. Heat shock protein 70 family signature motifs are highlighted as shaded regions (positions 30–37, 216–231 and 355–370). The signal peptide (position 1–15), ATP-binding motif (position 153–160) and consensus signature of endoplasmic reticulum form are underlined (position 653−656). The polyadenylation signal sites are shown in the open boxes (position 653–656). The stop codon is indicated by a star

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of HSP70 amino acid sequences of crustaceans. The HSP70 sequences of 35 crustacean species were analysed according to Jukes–Cantor genetic distance model and neighbour-joining method. Tree was rooted using Vibrio proteolyticus DNAK as outgroup. The scale bar represents 0.07 substitutions per site. The GenBank accession numbers of the amino acid sequences are provided after each species name, and the cloned E. affinis sequence is identified in bold. Four functional groups of the sequences can be highlighted as reticulum endoplasmic forms (identified as GRP78), decapod cytosolic inducible forms (identified as Decapod HSP70), decapod cytosolic constitutively expressed forms (identified as Decapod HSC70) and non-decapod cytosolic forms (identified as Non-decapod HSP70)

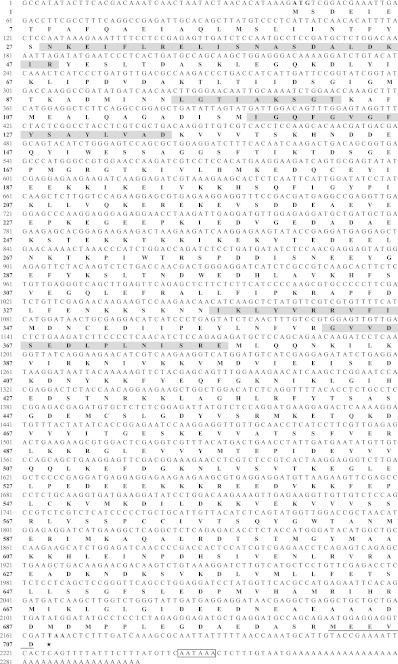

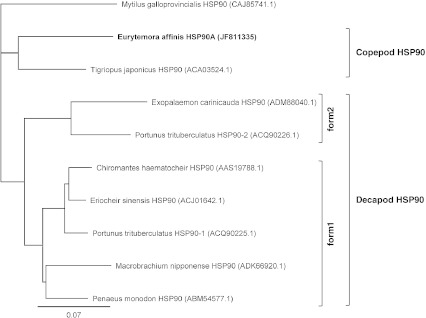

Degenerate primer pair DP-hsp90.F/DP-hsp90.R allowed amplification of a fragment of 364 bp which, after Blast analysis appeared to correspond to a part of a hsp90 transcript. The full-length nucleotid sequence obtained from 5′- and 3′-RACE PCR is 2,299 bp with 2,124 bp ORF encoding 707 amino acids (Fig. 4; GenBank accession number, JF811335). The cDNA contains a 5′-UTR of 43 bp and 3′-UTR of 132 bp including a stop codon (TAA), a polyadenylation signal and a poly(A) tail. Predicted protein presents a calculated molecular mass of 80.77 kDa and a predicted isoelectric point of 4.94. No signal peptide was detected with the Signal P software. The deduced amino acid sequence displays all five conserved amino acid blocks distinctive of the HSP90 protein family described by Gupta et al. (1995): NKEIFLRELISN-[SA]-SDALDKIR (residues 28–48), LGTIA-[KR]-SGT (residues 95–103), IGQFGVGFYSA-[YF]-LVA-[ED] (residues 119–134), IKLYVRRVFI (residues 336–346) and GVVDS-[ED]-DLPLN-[IV]-SRE (residues 363–377; Fig. 4). Motif scan analysis showed that the amino acid sequence is divided into the ATP binding domain (residues 28–181; Pfam ID HATPase_c PF02518) and the functional domain of HSP90 (residues 184–707; Pfam ID HSP90 PF00183). The C-terminal consensus cytosolic motif, MEEVD, appeared at position 703–707. The alignment from multiple sources of cytosolic HSP90 underlined a high conservation degree within crustaceans, with identities ranging from 77.23% (Exopalaemon carinicauda; ADM88040.1) to 84.10% (T. japonicus; ACA03524.1), and over a wide range of organisms such as the mollusc M. galloprovincialis (80.28%; CAJ85741.1), the insect D. melanogaster (79.92%; NP_523899.1), or the vertebrates Xenopus laevis (79.33%; NP_001086624.1), M. musculus (78.85%; NP_034610.1), G. gallus (78.60%; NP_001103255.1) and D. rerio (77.68%; Q90474.3). Consequently, HSP90 sequence characterized in E. affinis in the present study was referred as a cytosolic HSP90 form, and designed as Ea-HSP90A. The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5) showed that the HSP90 sequences of copepod including Ea-HSP90A were distinct from HSP90 sequences of decapods. Within decapods, two groups could be differentiated: a first group including Portunus trituberculatus HSP90-form 1 (ACQ90225.1) and a second group including P. trituberculatus HSP90-form 2 (ACQ90226.1).

Fig. 4.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of HSP90A from Eurytemora affinis. Heat shock protein 90 family signature motifs are highlighted as shaded regions (positions 28–48, 95–103, 119–134, 336–346 and 363–377). The consensus cytosolic signature of cytosolic form is underlined (positions 703–707). The polyadenylation signal site is shown in the open box. The stop codon is indicated by a star

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree of HSP90 amino acid sequences of crustaceans. The HSP90 sequences of 8 crustacean species were analysed according to Jukes–Cantor genetic distance model and neighbour-joining method. Tree was rooted using Mytilus galloprovincialis HSP90 as outgroup. The scale bar represents 0.07 substitutions per site. The GenBank accession numbers of the amino acid sequences is provided after each species name, and the cloned E. affinis sequence is identified in bold. Two sequence groups can be defined as copepod HSP90 and decapod HSP90

Effects of temperature and salinity on the gene expression profiles in controlled laboratory conditions

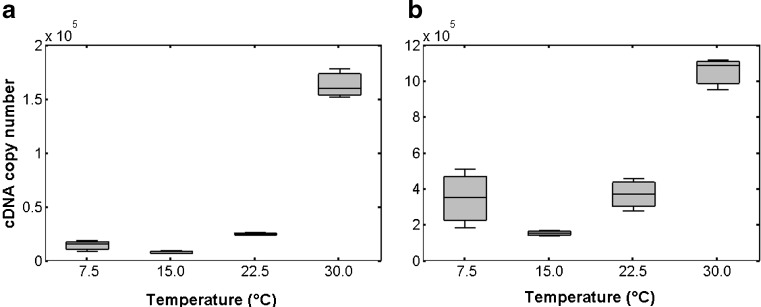

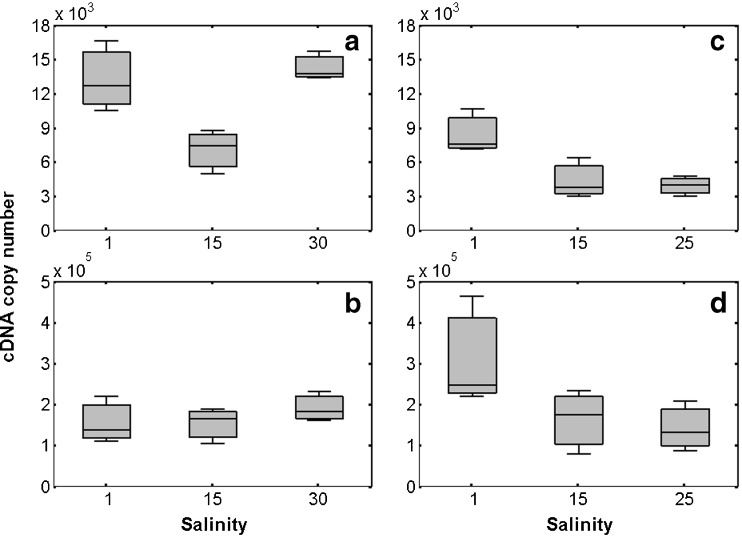

Expression profiles of Ea-grp78 and Ea-hsp90A obtained after different temperature and salinity treatments are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. Basically, the transcript level measured in controls (i.e. copepods kept in optimum rearing conditions: 15°C and salinity of 15) was in mean (n = 9) of 156,537 ± 17,163 cDNA copies for Ea-grp78 and 6,358 ± 810 cDNA copies for Ea-hsp90. Although the different experiments (from exposure to transcript quantification) were performed independently, the inter-experiment variation coefficients calculated from mean expression values of each control were 4% and 20% for Ea-grp78 and Ea-hsp90A genes, respectively. These results attest the reproducibility of the RT-qPCR procedure used in this study.

Fig. 6.

Levels of Ea-hsp90A (a) and Ea-grp78 (b) transcripts measured in pools of adult Eurytemora affinis after a 90-min thermic shock. The 15°C group corresponds to control condition. Boxes extend from the lower to the upper quartile with an internal segment for the median (n = 3); the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points

Fig. 7.

Levels of Ea-hsp90A (a, c) and Ea-grp78 (b, d) transcripts measured in pools of adult Eurytemora affinis after a 90-min osmotic shock (a, b) or a 72-h period of exposition to different salinities (c, d). The salinity 15 group corresponds to control condition. Boxes extend from the lower to the upper quartile with an internal segment for the median (n = 3); the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points

Significant up-regulations were observed in copepods exposed to thermic shocks during 90 min, for both Ea-hsp90A and Ea-grp78 transcripts (Fig. 6). The quantity of Ea-hsp90A transcripts reached 1.7-, 3.0- and 19.7-fold inductions in organisms shocked at temperatures of 7.5°C, 22.5°C and 30°C, respectively, in comparison to control (p < 0.05; Fig. 6a). To a lesser extent, the Ea-grp78 gene expression was significantly 2.3-, 2.4- and 6.9-fold more expressed, respectively, in comparison with the control (p < 0.05; Fig. 6b).

On one hand, hypo- and hyper-osmotic shocks (i.e. salinities of 1 and 30) during 90 min caused a 2-fold induction of Ea-hsp90A gene expression in comparison to controls (Unilateral Mann–Whitney rank sum test; p values < 0.05; Fig. 7a), whereas no significant change was measured for Ea-grp78 (Fig. 7b). On the other hand, similar expression profiles were observed for the two transcripts after 72 h of exposition to salinities of 1 and 25 (Fig. 7c, d). A significant 2-fold induction was observed in copepods kept at salinity of 1 (p < 0.05), whereas no change of transcription level was recorded at the salinity of 25, in comparison to controls.

Spatial and temporal variability of the gene expression profiles in Seine Estuary population

All samples were analysed at the same time (from total RNA extraction to transcript quantification). Data are presented in Table 1. Significant changes of Ea-grp78 and Ea-hsp90A gene expression were observed throughout the different sampling (Kruskal–Wallis rank sum tests: H (7, N = 40) = 30.4, p = 0.0001). The lowest levels were observed during the sampling campaign of April 2009 for a salinity of 4.2 and a water temperature of 14.7 ± 0.9°C: 6,523 ± 1,881 and 243,995 ± 76,075 cDNA copies for Ea-hsp90A and Ea-grp78 representing 1- and 1.6-fold the mean level of copepods kept in optimum laboratory rearing conditions, respectively (see the “Effects of temperature and salinity on the gene expression profiles in controlled laboratory conditions” section). The transcription levels recorded at the others salinities (10, 15 and 20) during this sampling campaign did not exceed 2.5-fold the mean levels previously observed in laboratory controls. Conversely, strong increases of Ea-grp78 and Ea-hsp90A gene expression were observed during sampling campaigns of June 2009 and May 2010, for respective water temperatures of 20.0°C and 16.3 ± 0.4°C. In May 2010, the quantity of transcripts tended to increase gradually inversely to salinity. The highest expression levels observed for a salinity of 4.8 were 10- and 6-fold the mean level of laboratory control for Ea-hsp90A and Ea-grp78, respectively. In the same way, the expression levels of copepods sampled in June 2009, at a salinity of 0.5, were 6- and 8-fold the mean level of laboratory control for Ea-hsp90A and Ea-grp78, respectively.

Discussion

Characterization of E. affinis GRP78 and HSP90A sequences

In the present study, we characterized the full-length cDNA of the grp78 gene from the calanoid copepod E. affinis, designed as Ea-grp78. To our knowledge, this is the first report concerning a grp78 cDNA sequence cloned from Copepoda. More generally, cDNA sequences of grp78 have been cloned from only two other crustacean species, the water fleas D. tibetana (FJ907314) and the Chinese shrimp F. chinensis (EF032651). The deduced amino acid sequence, Ea-GRP78, contained the three conserved HSP70 family signatures. All homologs of HSP70 proteins display an N-terminal ATPase domain, which is essential for active chaperone-mediated folding (Bukau and Horwich 1998). Ea-GRP78 displayed a motif very close to ATP/GTP-binding site motif A ([AG]-x(4)-GK-[ST]), AEAYLGKK (residues 153–161). This ATP/GTP-binding site motif was also found in GRP78 sequences from D. tibetana (AEAYLGKK, residues 158–166) and F. chinensis (AEAYLGKP, residues 156–163; Luan et al. 2009), as well as in cytosolic HSP70 sequences of other crustacean species such as the prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii (AEAFLGST at position 131–138 for Mar-HSC70 and AEAYLGKT at position 71–78 for Mar-HSP70; Liu et al. 2004) and the shrimps Microcaris fortunanta and R. exoculata (AEAFLGGT at position 131–138, and AESYLGKK at position 84–91, respectively; Ravaux et al. 2007). The signal peptide at the N terminus and the consensus tetrapeptide KDEL at the C terminus of the amino acid sequence, ensure the protein targeting to the ER. Membership of the sequence presently characterized to GRP78 protein group was confirmed by its high identity with GRP78 of a wide range of organisms (from nematodes to mammalians), in comparison to the low identity that it shares with cytosolic HSP70 forms of other crustacean species. The phylogenetic tree of known HSP70 sequence within crustaceans clearly illustrates the distinction between the group of GRP78 and the group of cytosolic HSP70. This last group is by far the most represented since it regroups more than 90% of HSP70 sequences characterized in crustaceans. As previously reported by Cottin et al. (2010), the sequences of inducible and constitutive cytosolic forms from decapod crustaceans appeared in separate groups in the phylogenetic tree. The classification given by the tree is in accordance with the results of functional studies performed in some species such as Palaemonetes varians and R. exoculata (Cottin et al. 2010) and M. rosembergii (Liu et al. 2004). However, this classification between inducible and constitutive cytosolic forms highlights a gap of sequence annotation since among 17 sequences corresponding to the constitutive cytosolic form, only 6 are clearly identified as HSC70. The classification of cytosolic forms in non-decapod crustacean species is more difficult to discuss, because only one sequence is available for each species, and more generally much lesser works have been performed in these organisms in spite of their eco-physiological interest as well their key role in aquatic ecosystems.

We also characterized the complete cDNA sequence of a cytosolic hsp90 gene from E. affinis, designed Ea-hsp90A (GenBank accession numbers: JF811335), in reference to the nomenclature system that was proposed by Chen et al. (2005a). The Ea-HSP90A deduced amino acid sequence contained the five conserved HSP90 family signatures (Gupta 1995), and an ATP-binding domain, essential for basic functions of HSP90 (Prodomou et al. 1997). In addition, the consensus motif MEEVD at the C terminus suggested that Ea-HSP90A belongs to the cytosolic HSP90 family (Gupta 1995). In accordance, Ea-HSP90A displayed high homologies with cytosolic HSP90 sequences from a wide range of organisms including invertebrates and higher vertebrates. In crustaceans, only 8 HSP90 sequences are available on the GeneBank database, 7 of which have been cloned from decapod species. Only one HSP90 sequence was known in copepods, which belongs to T. japonicus (ACA03524.1). As expected, Ea-HSP90 displayed the maximum identity with HSP90 of T. japonicus (84%). In invertebrates, it has been considered that a unique cytoplasmic HSP90 exists, which can be encoded by a single or two genes (Pantzartzi et al. 2009). However, Zhang et al. (2009) isolated two hsp90 mRNA (identified as hsp90-form 1 and hsp90-form 2) with distinct expression patterns, which encoded two distinct HSP90s, in marine crab Portunus trituberculatus. The phylogenetic analysis, performed in this study, indicates that the divergence between the two forms of cytosolic HSP90 occurred among decapod evolution. Indeed, HSP90 sequences of copepods are distinct from HSP90 sequences of decapods, which subdivided into a group including P. trituberculatus HSP90-form 1 and another group including P. trituberculatus HSP90-form 2. Nevertheless, this conclusion is speculative and further works should be conducted on non-decapod species to confirm this hypothesis.

Expression patterns of grp78 and hsp90 in E. affinis: laboratory and field studies

The RT-real time PCR procedure was successfully adapted to E. affinis. Although normalization of target gene expression against expression of endogenous genes considered as invariant (“housekeeping genes” or “reference genes”) is certainly the most used method in RT-pPCR, we opted, in this study, for a standardized method of absolute quantification. Indeed, as underlined by Bustin et al. (2009) no universal reference gene exists and normalizing to a regulated reference gene will distort data leading to wrong conclusions. So stability of a reference gene should be validated for both particular tissues or cell types, and experimental designs. In optimal condition, normalization may be improved by using the geometric average of multiple validated reference genes. However, in the context of the present study, validation of reference genes has been very tedious since our knowledge of transcriptome is limited in lot of invertebrate species studied in ecological physiology such as copepods. Besides, the validation of candidate genes as reference in perspective of in situ application could be very difficult, if we consider the diversity and the variability of environmental factors, which possibly influence their transcription levels. The results showed that the methodology used in this study is precise and robust. Indeed, although the different laboratory experiments were performed independently (from exposure to transcript quantification), the quantification of Ea-grp78 and Ea-hsp90A transcripts measured from controls exhibited a low inter-experimental variability.

Compared with the progress made in the functional study of HSP70 cytosolic isoforms, few studies focused on GRP78 or HSP90 in crustaceans. In this paper, the expression patterns of Ea-grp78 and Ea-hsp90A were analysed from copepods subjected to different controlled stresses in laboratory in order to validate their functionality and assess the potential effects of two important environmental factors of estuarine ecosystem, temperature and salinity. Transcript levels of both genes was significantly induced by thermal heat and cold shocks during 90 min. Ea-hsp90A inductions of 2- and 3-fold were observed after the shocks at 7.5°C and 22.5°C, whereas treatment at 30°C resulted in a radical 20-fold increase. In a lesser extent, Ea-grp78 was from 2- to 7-fold more expressed in treated copepods. In laboratory as well as field conditions, the density of E. affinis drops during summer temperature (∼20°C) compared to the optimal spring temperature of 15°C (Devreker et al. 2010). In parallel, a very low fecundity of females, coupled with a decrease of potential for recruitment were observed within the Seine Estuary population during a long negative anomaly of late winter temperature observed during 2005 when the lowest values of temperatures dropped to 5°C (Devreker et al. 2010). That tends to show that the low inductions of hsp genes recorded during our experiment (at 7.5°C and 22.5°C) transcribe a thermic stress sufficient to affect life history traits. This observation is in accordance with previous laboratory studies which have shown that very small amounts of temperature induced HSP can have effects on organism life traits (Sørensen et al. 2003). It could be interesting to continue the study of links between hsp gene inductions and life trait alterations in E. affinis to precise interpretation of this molecular tool in perspective of physiological ecology applications. Similar gene expression patterns were reported in hepatopancreas and gills of the crab P. trituberculatus for the two HSP90 isoforms (HSP90-form 1 and HSP90-form 2; Zhang et al. 2009). The authors observed more important inductions in heat-shocked (30°C) organisms in comparison to cold-shocked (10°C) ones. The expression pattern of P. trituberculatus hsp90 from 2 genes, which displays the highest induction levels, is the closest to one described in this study for Ea-hsp90. In the same way, Li et al. (2009) reported important inductions (until 12-fold the expression level of control) in the Chinese shrimp F. chinensis. Conversely, in spite of the phylogenetic nearby with E. affinis, very light fluctuations of hsp90 transcripts were observed in copepod T. japonicus shocked at 35°C (Rhee et al. 2009). Some works have shown that HSP90 can be also induced by heat shock in other aquatic invertebrates such as the molluscs Haliotis tuberculata (Farcy et al. 2007), Laternula elliptica (Kim et al. 2009) and Haliotis discus (Wang et al. 2011). To our knowledge, only Luan et al. (2009) have previously performed functional study of GRP78 in another crustacean species. In line with our results, these authors showed that expression of grp78 was up-regulated (up to 2.4-fold) by heat shock in the Chinese shrimp F. chinensis. Concerning the effects of salinity, Ea-hsp90 and Ea-grp78 expression were assessed after short- (90 min) and long-term (72 h) exposures to hypo- (salinity of 1) and hyper-osmotic stresses (salinity of 25–30) in comparison with control condition (salinity of 15). The two genes showed different responses after osmotic-shock treatments. Indeed, after a 90-min exposure, no modification of Ea-grp78 transcript level was recorded whereas the both hypo- and hyper-osmotic stresses significantly induced a 2-fold increase of the Ea-hsp90A transcript quantity. Inversely, similar patterns were observed for Ea-hsp90A and Ea-grp78 after long-term exposure. A significant 2-fold increase of transcript levels was observed in copepods kept at the salinity of 1, but no fluctuation was recorded at the salinity of 25. Impairment of development and survival of early life stage (i.e. nauplii larval stages) have been previously observed in E. affinis long-term exposed at the salinity of 1 (Devreker et al. 2004). This would agree the stress transcribed by the hsp gene inductions recorded in the same conditions. Nevertheless, the authors equally showed that the long-term exposure to high salinity (25) induced more important and significant effects on a large range of life history traits (e.g. reproduction and survival of adult stage; Devreker et al. 2007, 2009), whereas no induction of hsp genes was observed in our study excepted for Ea-hsp90A at short-term exposure. So, in opposition to previous discussion about thermic stress, the link between physiological response and the effects on the life traits is unclear in the case of osmotic stress. This gap highlights the need to obtain more detailed understanding of eco-physiological role of HSPs. Our results corroborate the works of Spees et al. (2002) that report significant expression induction of cytosolic HSP90s in the lobster Homarus americanus after both hypo- and hyper-osmotic shocks. The authors observed an hsp90 induction up to 600% and 300% of control transcript level, at low and high salinities. The greater response observed in lobster compared to E. affinis might result in part of the poor osmo-regulative capacities of this stenohaline species. Oppositely, Zhang et al. (2009) have shown that hsp90-form 1 and hsp90-form 2 were down-regulated in the hepatopancreas, muscle and ovary of P. trituberculatus exposed short-term to low or high salinity. These authors suggested that the osmotic stresses may exceed the tolerance of these tissues and turn lead to the cell death. Some works have shown that hsp90 can also be induced by osmotic shock in other aquatic organisms such as the Altlantic salmon, Salmo salar (Pan et al. 2000), or the oyster, Crassostrea hongkongensis (Fu et al. 2011). By contrast, to our knowledge, no study has reported the effect of osmotic stress on the GRP78 synthesis level.

Most of the published works report the effects of an acute or repetitive stress on the physiology of organisms exposed in laboratory. Although such approaches are necessary to provide specific biological response to a given stress in controlled conditions, they are less representative than fieldworks since they do not allow adequately assessing the combination of biotic and abiotic factors found in natural conditions (Lejeusne et al. 2006). Nevertheless, long-term in situ applications within natural populations are still relatively scarce (e.g. Hofmann and Somero 1995; Lejeusne et al. 2006; Minier et al. 2000). In the present study, the expression of Ea-grp78 and Ea-hsp90A genes was measured from copepods directly sampled into the natural population of the Seine Estuary along of the salinity gradient, on the occasion of three test campaigns. For that, organisms of adult stage—males and females in sexual rest—were rigorously selected in order to minimize the potential influence of seasonal population structure variations. On one hand, the levels of hsp gene expression recorded in April 2009 for water temperature of 15°C, stayed relatively constant for salinities ranged from 5 to 20, and were closed to ones measured in copepods kept in optimal laboratory conditions. These results mean that the copepods sampled at this date did not seem to display physiological stress. That is in accordance with some previous works, which showed that the spring is the most favourable period for E. affinis population dynamic in Seine Estuary (Mouny and Dauvin 2002). Indeed, these authors recorded maximal density values for this period when temperatures are ranged from 10°C to 15°C. These temperatures equally correspond to the best recruitment success observed during laboratory study (Devreker et al. 2007, 2009). On the other hand, we observed strong inductions of hsp gene expression (up to 10- and 6-fold the mean level of laboratory control for Ea-hsp90A and Ea-grp78) in copepods sampled at low salinity during the campaign of June 2009 and May 2010, when water temperature of Seine Estuary increases. These results tend to show that the low salinity and the increase of temperature seem to have a synergic effect on stress condition of copepods. However, other potential biotic or abiotic factors (e.g. pH, dissolved O2 or pollution) not considered in the present study could also greatly influence the expression levels of the two HSPs studied (Lejeusne et al. 2006). In any case, the results obtained during this preliminary fieldwork underline the interest to estimate and quantify the role of HSPs in the ecology of E. affinis during long-term monitoring of natural populations. Therefore, in actual context of environmental changes including global warming, pollution and habitat fragmentation, the development and validation of relevant stress indicators is fundamental to improve the detection and the interpretation of biological consequences on organisms and populations (Sørensen et al. 2003).

Acknowledgements

This study is a contribution to ZOOSEINE project funded by Seine-Aval IV program within the framework of the project aiming at building bioindicators based on the estuarine copepod Eurytemora affinis.

References

- Beyrend-Dur D, Souissi S, Devreker D, Winkler G, Hwang J-S. Life cycle traits of two transatlantic populations of Eurytemora affinis (Copepoda: Calanoida): salinity effects. J Plankton Res. 2009;31(7):713–128. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbp020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B, Horwich AL. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone machines. Cell. 1998;92(3):351–366. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55(4):611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Piel WH, Gui L, Bruford E, Monteiro A. The HSP90 family of genes in the human genome: insights into their divergence and evolution. Genomics. 2005;86(6):627–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ, Zhou Z, Lee DH, Nguyen JT, Barbisin M, Xu NL, Mahuvakar VR, Andersen MR, Lao KQ, Livak KJ, Guegler KJ. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem–loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(20):e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottin D, Shillito B, Chertemps T, Thatje S, Léger N, Ravaux J. Comparison of heat-shock responses between the hydrothermal vent shrimp Rimicaris exoculata and the related coastal shrimp Palaemonetes varians. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2010;393(1–2):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2010.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dauvin JC, Desroy N. The food web in the lower part of the Seine estuary: a synthesis of existing knowledge. Hydrobiologia. 2005;540(1–3):13–27. doi: 10.1007/s10750-004-7101-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devreker D, Souissi S, Seuront L. Development and mortality of the first naupliar stages of Eurytemora affinis (Copepoda, Calanoida) under different conditions of salinity and temperature. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2004;303(1):31–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2003.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devreker D, Souissi S, Forget-Leray J, Leboulenger F. Effects of salinity and temperature on the post-embryonic development of Eurytemora affinis (Copepoda; Calanoida) from the Seine estuary: a laboratory study. J Plankton Res. 2007;29(suppl 1):i117–i133. [Google Scholar]

- Devreker D, Souissi S, Molinero J-C, Nkibuto F. Trade-offs of the copepod Eurytemora affinis in mega-tidal estuaries. Insights from high frequency sampling in the Seine Estuary. J Plankton Res. 2008;30(12):1329–1342. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbn086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devreker D, Souissi S, Winkler G, Forget-Leray J, Leboulenger F. Effects of salinity, temperature and individual variability on the reproduction of Eurytemora affinis (Copepoda; Calanoida) from the Seine estuary: a laboratory study. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2009;368(2):113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2008.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devreker D, Souissi S, Molinero J-C, Beyrend-Dur D, Gomez F, Forget-Leray J. Tidal and annual variability of the population structure of Eurytemora affinis in the middle part of the Seine Estuary during 2005. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2010;89(4):245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2010.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Ashton B, Buxton S, Cheung M, Cooper A, Duran C, Field M, Heled J, Kearse M, Markowitz S, Moir R, Stones-Havas S, Sturrock S, Thierer T, Wilson A (2011) Geneious v5.4, available from http://www.geneious.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Farcy E, Serpentini A, Fiévet B, Lebel J-M. Identification of cDNAs encoding HSP70 and HSP90 in the abalone Haliotis tuberculata: transcriptional induction in response to thermal stress in hemocyte primary culture. Comp Biochem Physiol B-Biochemi Molec Biol. 2007;146(4):540–550. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D, Chen J, Zhang Y, Yu Z (2011) Cloning and expression of a heat shock protein (HSP) 90 gene in the haemocytes of Crassostrea hongkongensis under osmotic stress and bacterial challenge. Fish Shellfish Immun. doi:10.1016/j.fsi.2011.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez CRM, Bradley BP. Salinity stress proteins in Eurytemora affinis. Hydrobiologia. 1994;292–293(1):461–468. doi: 10.1007/BF00229973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RS. Phylogenetic analysis of the 90 kD heat shock family of protein sequences and an examination of the relationship among animals, plants and fungi species. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12(6):1063–1073. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakimzadeh R, Bradley BP. The heat shock response in the copepod Eurytemora affinis (POPPE) J Therm Biol. 1990;15(1):67–77. doi: 10.1016/0306-4565(90)90050-R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann GE. Patterns of Hsp gene expression in ectothermic marine organisms on small to large biogeographic scales. Integr Comp Biol. 2005;45(2):247–255. doi: 10.1093/icb/45.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann GE, Somero GN. Evidence for protein damage at environmental temperatures: seasonal changes in levels of ubiquitin conjugates and hsp70 in the intertidal mussel Mytilus trossulus. J Exp Biol. 1995;198:1509–1518. doi: 10.1242/jeb.198.7.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin S, Brocchieri L. Heat shock protein 70 family: multiple sequence comparisons, function, and evolution. J Mol Evol. 1998;47(5):565–577. doi: 10.1007/PL00006413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Ahn I-Y, Kim H, Cheon J, Park H. Molecular characterization and induction of heat shock protein 90 in the Antarctic bivalve Laternula elliptica. Cell Stress Chaperon. 2009;14(4):363–370. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0090-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel DG, Bradley BP. Specific protein responses in the calanoid copepod Eurytemora affinis (Poppe, 1880) to salinity and temperature variation. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2001;266(2):135–149. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(01)00352-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel DG, Miller WD, Roman MR. Regional scale climate forcing of mesozooplankton dynamics in Chesapeake Bay. Estuar Coasts. 2006;29(3):375–387. [Google Scholar]

- Laprise R, Dodson J-J. Environmental variability as a factor controlling spatial patterns in distribution and species diversity of zooplankton in the St. Lawrence Estuary. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1994;107(1–2):67–81. doi: 10.3354/meps107067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CE. Rapid and repeated invasions of fresh water by the copepod Eurytemora affinis. Evolution. 1999;53(5):1423–1434. doi: 10.2307/2640889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AS. The glucose-regulated proteins: stress induction and clinical applications. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26(8):504–510. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01908-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CE, Peterson CH. Effects of developmental acclimation on adult salinity tolerance in the freshwater-invading copepod Eurytemora affinis. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2003;76(3):296–301. doi: 10.1086/375433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeusne C, Pérez T, Sarrazin V, Chevaldonne P. Baseline expression of heat-shock proteins (HSPs) of a “thermotolerant” Mediterranean marine species largely influenced by natural temperature fluctuations. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2006;63(9):2028–2037. doi: 10.1139/f06-102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Luan W, Zhang C, Zhang J, Wang B, Xie Y, Li S, Xiang J. Cloning of cytoplasmic heat shock protein 90 (FcHSP90) from Fenneropenaeus chinensis and its expression response to heat shock and hypoxia. Cell Stress Chaperon. 2009;14(2):161–172. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0069-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S. The heat-shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–1191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yang W-J, Zhu X-J, Karouna-Renier NK, Rao RK. Molecular cloning and expression of two HSP70 genes in the prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Cell Stress Chaperon. 2004;9(3):313–323. doi: 10.1379/CSC-40R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan W, Li F, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang J. Cloning and expression of glucose regulated protein 78 (GRP78) in Fenneropenaeus chinensis. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36(2):289–298. doi: 10.1007/s11033-007-9178-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan W, Li F, Zhang J, Wen R, Li Y, Xiang J. Identification of a novel inducible cytosolic Hsp70 gene in Chinese shrimp Fenneropenaeus chinensis and comparison of its expression with the cognate Hsc70 under different stresses. Cell Stress Chaperon. 2010;15(1):83–93. doi: 10.1007/s12192-009-0124-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer MP, Bukau B. Hsp70 chaperones: cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(6):670–684. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4464-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minier C, Borghi V, Moore MN, Porte C. Seasonal variation of MXR and stress proteins in the common mussel, Mytilus galloprovincialis. Aquat Toxicol. 2000;50(3):167–176. doi: 10.1016/S0166-445X(99)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouneyrac C, Roméo M. Stress proteins and the acquisition of tolerance. In: Amiard-Triquet C, Rainbow PS, Roméo M, editors. Tolerance to environmental contaminants. London: Taylor & Francis Group; 2011. pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Mouny P, Dauvin JC. Environmental control of mesozooplankton community structure in the Seine estuary (English Channel) Oceanol Acta. 2002;25(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/S0399-1784(01)01177-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadam J, Navarro F, Sanchez P, Moulin C, Georges B, Laglaine A, Pequignot J-M, Morales A, Ryvlin P, Bezin L. Neuroprotective effects of erythropoietin in the rat hippocampus after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;25(2):412–416. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan F, Zarate JM, Tremblay GC, Bradley TM. Cloning and characterization of Salmon hsp90 cDNA: upregulation by thermal and hyperosmotic stress. J Exp Zool. 2000;287(3):199–212. doi: 10.1002/1097-010X(20000801)287:3<199::AID-JEZ2>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantzartzi CN, Kourtidis A, Drosopoulou E, Yiangou M, Scouras ZG. Isolation and characterization of two cytoplasmic hsp90s from Mytilus galloprovincialis (Mollusca: Bivalvia) that contain a complex promoter with a p53 binding site. Gene. 2009;431(1–2):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodomou C, Roe SM, O’Brien R, Labdury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Identification and structural characterisation of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Cell. 1997;90(1):65–75. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravaux J, Toullec J-Y, Léger N, Lopez P, Gaill F, Shillito B. First hsp70 from two hydrothermal vent shrimps, Mirocaris fortunata and Rimicaris exoculata: characterization and sequence analysis. Gene. 2007;386(1-2):162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee J-S, Raisuddin S, Lee K-W, Seo JS, Ki J-S, Kim I-C, Park HP, Lee J-S. Heat shock protein (Hsp) gene responses of the intertidal copepod Tigriopus japonicus to environmental toxicants. Comp Biochem Phys C. 2009;149(1):104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen JG, Kristensen TN, Loeschcke V. The evolutionary and ecological role of heat shock proteins. Ecol Lett. 2003;6(11):1025–1037. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00528.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spees JL, Chang SA, Snyder MJ, Chang ES. Osmotic induction of stress-responsive gene expression in the Lobster Homarus americanus. Biol Bull. 2002;203:331–337. doi: 10.2307/1543575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Whang I, Lee J-S, Lee J. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of a heat shock protein 90 gene from disk abalone (Haliotis discus) Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38(5):3055–3060. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-9972-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong ML, Medrano JF. Real-time PCR for mRNA quantitation. Biotechniques. 2005;39(1):75–85. doi: 10.2144/05391RV01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuereb B, Bezin L, Chaumot A, Budzinski H, Augagneur S, Tutundjian R, Garric J, Geffard O. Vitellogenin-like gene expression in freshwater amphipod Gammarus fossarum (Koch, 1835): functional characterization in females and potential for use as endocrine disruption biomarker in males. Ecotoxicol. 2011;20(6)):1286–1299. doi: 10.1007/s10646-011-0685-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X-Y, Zhang M-Z, Zheng C-J, Liu J, Hu H-J. Identification of two hsp90 genes from the marine crab, Portunus trituberculatus and their specific expression profiles under different environmental conditions. Comp Biochem Phys C. 2009;150:465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]