Abstract

Little information exists on the population prevalence or geographic distribution of injection drug users (IDUs) who are Hispanic in the USA. Here, we present yearly estimates of IDU population prevalence among Hispanic residents of the 96 most populated US metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) for 1992–2002. First, yearly estimates of the proportion of IDUs who were Hispanic in each MSA were created by combining data on (1) IDUs receiving drug treatment services in Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)’s Treatment Entry Data System, (2) IDUs being tested in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV-Counseling and Testing System, and (3) incident AIDS diagnoses among IDUs, supplemented by (4) data on IDUs who were living with AIDS. Then, the resulting proportions were multiplied by published yearly estimates of the number of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups in each MSA to produce Hispanic IDU population estimates. These were divided by Hispanic population data to produce population prevalence rates. Time trends were tested using mixed-effects regression models. Hispanic IDU prevalence declined significantly on average (1992 mean = 192, median = 133; 2002 mean = 144, median = 93; units are per 10,000 Hispanics aged 15–64). The highest prevalence rates across time tended to be in smaller northeastern MSAs. Comparing the last three study years to the first three, prevalence decreased in 82% of MSAs and increased in 18%. Comparisons with data on drug-related mortality and hepatitis C mortality supported the validity of the estimates. Generally, estimates of Hispanic IDU population prevalence were higher than published estimates for non-Hispanic White residents and lower than published estimates for non-Hispanic Black residents. Further analysis indicated that the proportion of IDUs that was Hispanic decreased in 52% and increased in 48% of MSAs between 2002 and 2007. The estimates resulting from this study can be used to investigate MSA-level social and economic factors that may have contributed to variations across MSAs and to help guide prevention program planning for Hispanic IDUs within MSAs. Future research should attempt to determine to what extent these trends are applicable to Hispanic national origin subgroups.

Keywords: Hispanics/Latinos, Racial/ethnic health disparities, Injection drug use, HIV/AIDS, Drug policy

Hispanic injection drug users (IDUs) are a particularly vulnerable population for a number of reasons. In the USA, IDUs who are Hispanic are more likely to be infected with HIV and hepatitis C than IDUs who are non-Hispanic White.1,2 Hispanics infected with HIV are twice as likely as non-Hispanic Whites to be diagnosed late in the course of their infection.3 Hispanic IDUs may be less likely to utilize HIV prevention services, or services for drug users, than non-Hispanics due to greater concern about stigma regarding drug use, HIV/AIDS, or the association between HIV/AIDS and homosexuality.4–7

Research on Hispanic IDUs is hampered by the lack of information on their number and geographic location over time. Such information could be used to better target HIV and hepatitis C prevention programs among Hispanic IDUs and to compare trends in injection drug use, HIV, and hepatitis C across racial/ethnic groups. Data on overall IDU prevalence and on IDU prevalence among non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black residents aged 15–64 of the 96 largest US metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) have been published for the 1992–2002 period.8,9 The current study fills a crucial gap by providing estimates of IDU population prevalence among Hispanic residents aged 15–64 in the same set of MSAs during the same time period. To extend the analysis to more recent years, we also examine change in the estimated proportion of IDUs who were Hispanic from 2002 to 2007.

Methods

We use the term “Hispanic” to indicate self-reported Hispanic or Latino ethnicity to be consistent with our sources of data. The federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) defines people of Hispanic ethnicity as “persons who trace their origin or descent to Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Central and South America, and other Spanish cultures.”10 The sources used in this study categorized participants into Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and other categories.

We use MSA as the geographic unit of analysis because MSAs are defined by the OMB to represent socially and economically integrated entities, made up of contiguous counties that contain a central city of 50,000 people or more.11 They are likely to reflect social and economic integration among IDUs.12 We obtained yearly estimates of the MSA populations aged 15–64 for Hispanics and for residents of all racial/ethnic groups from publically available Census data.13

To estimate Hispanic IDU prevalence, we multiplied yearly estimates of the proportion of IDUs who were Hispanic (averaging proportions from three sources, described below) in each MSA by yearly published estimates of the number of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups in each MSA. Since overall IDU prevalence estimates were available for 1992–2002, the timeframe for the current study is also 1992–2002. The calculation is summarized in formula 1.

|

1 |

where HIDUij = estimated prevalence of IDUs among Hispanic residents, aged 15–64, in study year i, MSA j; ProportionHij = estimated proportion of IDUs who were Hispanic in study year i, MSA j; IDUNij = published estimated number of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups, aged 15–64, in study year i, MSA j; PopulationHij = number of residents who were Hispanic, aged 15–64, in study year i, MSA j.

Combining Source Data

The proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic were estimated by combining three data series: (1) HIV-Counseling and Testing Services (CTS),14 (2) Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS),15 and (3) data on incident AIDS diagnoses among people who reported injection drug use as the route of HIV acquisition, supplemented with data on people living with AIDS who reported injection drug use as the route of HIV acquisition.16

HIV-Counseling and Testing Services

CTS data on IDUs receiving HIV-counseling and testing services were obtained from the CDC by special arrangement.14 We calculated the proportions of IDUs receiving services in CTS data who were Hispanic as an indicator for the proportions of the IDU populations who were Hispanic. Of the 95 MSAs included in analyses of the proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic, 77 contributed CTS data. Complete yearly data were available for 52 MSAs; data were available for some years for 25 additional MSAs. Data were incomplete for three reasons: (1) Some health departments reported only aggregated data that could not be matched geographically to the MSAs in our study, (2) data from cells that contained fewer than five individuals were redacted (removed) by the CDC in order to protect against loss of participant confidentiality, and (3) we excluded existing data for 1 year from two MSAs in order to avoid proportion estimates that could be unreliable due to small numbers of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups (fewer than 20).

Treatment Episode Data Set

TEDS data indicate the number and characteristics of people entering substance abuse treatment programs that receive funding from the federal government. TEDS data are managed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and are publically available.17 We calculated the proportions of IDUs entering drug treatment in TEDS data who were Hispanic as an indicator for the proportions of the IDU populations who were Hispanic. Of the 95 MSAs included in analyses of the proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic, complete yearly data were available for 88 MSAs, and data were available for some years for three additional MSAs. Data from four MSAs could not be used because route of drug administration (injection or non-injection) was not collected or coded. We excluded data for 1 year in three MSAs in order to avoid proportion estimates that could be unreliable due to small numbers of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups (fewer than 20).

IDU Incident AIDS Diagnoses and People Living with AIDS

We obtained data representing incident AIDS diagnoses (IAIDS) and people living with AIDS (PLWA) attributed to injection drug use from the CDC by special arrangement. We calculated the proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic in IAIDS data, with adjustment for HIV prevalence (described below), as an indicator for the proportions of the IDU populations who were Hispanic. IAIDS data may be more likely to capture IDUs who did not access HIV-counseling and testing or drug treatment services. However, IAIDS data were sparse in some years in some MSAs. We excluded Hispanic proportion data for some years from 28 MSAs in order to avoid proportion estimates that could be unreliable due to small numbers of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups (fewer than 20). After this exclusion, yearly Hispanic IDU proportions were available for 52 MSAs and for some years for 32 additional MSAs. Fortunately, PLWA data were more complete and were consistent with IAIDS data (the average Pearson correlation between Hispanic proportions of IDUs in IAIDS and PLWA data across study years was 0.96), so we used the proportion of IDU PLWA who were Hispanic as a proxy where IAIDS data were missing. After filling in these data, 93 of the 95 MSAs included in analyses of the proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic contributed yearly IAIDS data. Hispanic IAIDS data were not available for two MSAs because states in which parts of the MSAs were located did not agree to provide the data by race/ethnicity.

Adjustment of IDU Incident AIDS Diagnoses for the Proportion of IDUs Testing Positive for HIV

The proportion of IDU IAIDS cases that are Hispanic can be influenced by a number of factors, including racial/ethnic differences in HIV prevalence, utilization and effectiveness of HIV counseling and testing and HAART, and other factors related to progression to AIDS. To reduce potential bias due to variation among MSAs in relative HIV prevalence by race/ethnicity, we adjusted the proportion of IDUs who were Hispanic in IAIDS data (PIAIDS) for HIV prevalence among IDUs in CTS data using the following formula:

|

2 |

where HijIAIDS = the number of Hispanic IDU IAIDS cases in study year i, MSA j; Hij = the proportion of Hispanic IDUs testing positive for HIV in CTS data in study year i, MSA j; TijIAIDS = the number of IAIDS cases of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups in study year i, MSA j; Tij = the proportion of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups testing positive for HIV in CTS data in study year i, MSA j.

This formula assumes that the yearly HIV proportions of Hispanic IDUs and of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups in who test positive for HIV in CTS data in each MSA reflect HIV prevalence in their respective underlying populations. It is important to note that CTS data represent the number of tests and positive results, not the number of individuals testing positive.

Imputations to Estimate Missing HIV Test Result Data

CTS Data on the proportion testing positive for HIV among Hispanic IDUs and among IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups were incomplete due to inconsistent reporting, removal by the CDC of test result data from small cells (fewer than five positive results) to protect participant confidentiality, and exclusion of data on the proportion positive that would have been based on fewer than 20 Hispanic IDUs.

We imputed values to fill in missing CTS HIV data for Hispanic IDUs in two steps. First, in a binomial mixed-effects regression, we imputed values as a function of (a) year, (b) the proportion of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups testing positive for HIV, and (c) the proportion of IDUs tested who were Hispanic. Next, in MSAs where Hispanic IDU HIV data were missing for some years, we imputed missing values using predicted values from a linear mixed-effects regression on time. Mixed-effects regressions were performed using the SAS procedure PROC GLIMMIX (version 9.2). We imputed values to fill in missing CTS HIV data for IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups in a parallel manner, using year, the proportion of all CTS clients testing positive for HIV, and the proportion of CTS clients tested who were IDUs as predictors for the mixed-effects binomial regression. We used average values predicted by the binomial regressions of yearly proportions testing positive for HIV among Hispanic IDUs and IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups for 22 of the 93 MSAs contributing IAIDS data because CTS HIV test result data for those MSAs were missing for all study years.

Averaged Proportions of IDUs Who Were Hispanic

We created a complete data set of the proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic from the three data sources—CTS, TEDS, and IAIDS (supplemented with PLWA data and adjusted for HIV prevalence)—using predicted values from a binomial mixed-effects regression. We modeled Hispanic proportions using events/trials syntax with the number of Hispanic IDUs in the numerator and the number of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups in the denominator.18 Data sources were stacked so that each MSA and year was represented by as many cases as there were data sources (one, two, or all three sources). Data were available from all three sources for 72 MSAs, from any two sources for 18 MSAs, and from only one source for 5 MSAs. The model used all the available data to estimate parameters, even where some data were missing, under the assumption that the data were missing at random, conditional on the observed data. Dummy codes were used to compare data sources. We used a quadratic polynomial model of time to maintain consistency with procedures used to produce the overall IDU estimates.8 Intercepts were set to vary randomly using residual pseudo-likelihood estimation. Standard errors of the fixed effects were adjusted using the sandwich method.18

The resulting complete sets of proportions were averaged to create single yearly estimates of the proportion of IDUs who were Hispanic. These proportions were then multiplied by published estimates of the number of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups to produce estimates of the Hispanic IDU populations.

Published Population Data for IDUs of All Racial/Ethnic Groups

Procedures used to estimate the populations of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups in these MSAs are described in detail elsewhere.8 Briefly, we began with annual national estimates of the number of drug treatment entrants who were IDUs, the number of IDUs who were tested for HIV, the number of arrestees for heroin and cocaine possession multiplied by the proportion of treatment entrants treated for heroin or cocaine dependence who reported that they injected drugs, and regression-based interpolations and extrapolations of published estimates for the years 1992 and 1998.19,20 These national estimates were allocated to each MSA using multiplier methods and then smoothed to reduce stochastic variation with locally weighted regression.

Calculating Hispanic IDU Population Prevalence

By multiplying estimates of the proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic by the published estimated numbers of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups, we created estimates of the numbers of IDUs who were Hispanic. We calculated Hispanic IDU population prevalence by dividing these estimates by their respective Hispanic populations, aged 15–64. We used the published8 prevalence of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups as the prevalence of IDUs who were Hispanic in the San Juan–Bayamon, Puerto Rico MSA because CTS data were not collected, TEDS data were not collected by race/ethnicity, and IAIDS data indicated that few IDUs with AIDS were non-Hispanic.

Reliability

We assessed reliability of the data with yearly Pearson correlations of the three Hispanic IDU proportions (CTS, TEDS, IAIDS).

Validity

We assessed the validity of the Hispanic IDU prevalence estimates by assessing their correlations with two indicators of Hispanic injection drug use—drug-related mortality and hepatitis C mortality—among Hispanics. Mortality data were extracted from the Multiple Cause of Death data tabulated by the National Vital Statistics System.21 In these data, ICD-9 coding was used to identify causes of death between 1992 and 1998, and ICD-10 coding was used thereafter. Our coding of drug-related deaths was based on that of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.22 We coded drug-related deaths as “deaths happening shortly after consumption of one or more psychoactive drugs and directly related to this consumption,” and “accidental and unintentional drug poisoning deaths” that occurred after consuming cocaine, heroin, or psychostimulants. Route of drug administration was not used in the ICD coding, so we could not restrict drug-related deaths to those that were IDU-related. We restricted our analysis to deaths that occurred in the MSA of residence. Hepatitis C mortality data were available starting in 1999, when ICD-10 codes to identify hepatitis C (B17.1 and B18.2) were implemented.

Trend Analysis

We used a polynomial mixed-effects model with restricted maximum-likelihood estimation to investigate change in Hispanic IDU prevalence across time among MSAs. Although this selection of MSAs is not, strictly speaking, a sample, we use statistical significance tests as a heuristic guide. We log-transformed Hispanic IDU population prevalence rates before analysis because the rates were right-skewed.

To assess change across time in individual MSAs, we calculated percent change values comparing the earliest (1992–1994) and latest (2000–2002) 3 years of data. We use the average of 3 years to maximize the reliability of the comparisons within MSAs.

To assess trends after the period for which overall IDU prevalence data have been published, we examined the proportion of IDUs that was estimated to be Hispanic. First, we entered the proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic in CTS, TEDS, and IAIDS data from 2002 to 2007 into a polynomial mixed-effects model to assess overall time trends. Then we averaged across the three data series to create an overall estimate of the proportion of IDUs that was Hispanic. Finally, we calculated percent change values comparing proportions averaged over 2002–2004 to those averaged over 2005–2007, the most recent period with available data.

Results

Results from the binomial regression model of the proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic by data source are in Table 1. Anti-logit transforming the intercept gives the average predicted Hispanic proportion value among IAIDS cases—0.061 in 1992. Both the linear (years since 1992) and quadratic (years since 1992 squared) slopes are positive, but only the linear term is significant, indicating a linear increase over time on average. The CTS dummy code was not significant, indicating that Hispanic IDU proportions in CTS data were not different from those in IAIDS data. However, the TEDS dummy code was significant in the positive direction, indicating that TEDS Hispanic IDU proportions were almost 20% higher than those in IAIDS—0.073 on average in 1992.

Table 1.

Binomial mixed-effects regression results for the proportions of injection drug users who were Hispanic in three data sources, 1992–2002

| Estimate | Standard error | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.7336** | 0.1667 |

| Years since 1992 | 0.0132* | 0.0060 |

| Years since 1992 squared | 0.0008 | 0.0006 |

| Source | ||

| HIV-Counseling and Testing Services | −0.0352 | 0.0687 |

| Treatment Episode Data Set | 0.1870** | 0.0527 |

| Incident AIDS Diagnoses | 1.0 | – |

| Intercept variance | 2.7394 | 0.4034 |

N = 96 metropolitan statistical areas

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Pearson correlations among the three estimates of the proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic showed good consistency. Correlations between CTS and TEDS proportions ranged from 0.90 to 0.93 across years (mean = 0.91), while those between CTS and IAIDS ranged from 0.51 to 0.85 (mean = 0.74) and those between TEDS and IAIDS ranged from 0.60 to 0.80 (mean = 0.71).

We calculated a single yearly proportion of IDUs who were Hispanic in each MSA by averaging the set of proportions from the three sources. We multiplied the averaged proportions by published estimates of the populations of IDUs of all racial/ethnic groups and divided the results by the respective Hispanic MSA populations to produce population prevalence estimates.

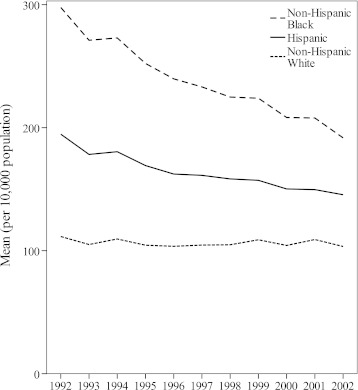

Descriptive data for the yearly Hispanic IDU population prevalence estimates are in Table 2. The estimates show a substantial decline from 1992 (mean = 192, median = 133) to 2002 (mean = 144, median = 93; units are per 10,000 Hispanics aged 15–64). Hispanic IDU prevalence declined more sharply initially, then more slowly, with fluctuations, forming a slightly curvilinear relationship with time. Figure 1 depicts average IDU prevalence among Hispanic residents, compared with previously published data for non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White residents across time.9 Generally, estimates of Hispanic IDU population prevalence were higher than published estimates for non-Hispanic White residents and lower than published estimates for non-Hispanic Black residents.

Table 2.

Estimated prevalence of Hispanic injection drug users per 10,000 Hispanic residents aged 15–64, 1992–2002

| Year | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 192 | 189 | 21 | 1068 | 133 | 68, 239 |

| 1993 | 178 | 178 | 16 | 931 | 110 | 58, 232 |

| 1994 | 178 | 184 | 16 | 1070 | 115 | 61, 217 |

| 1995 | 168 | 175 | 11 | 905 | 101 | 53, 222 |

| 1996 | 162 | 173 | 11 | 874 | 95 | 51, 208 |

| 1997 | 158 | 172 | 9 | 840 | 95 | 49, 198 |

| 1998 | 155 | 172 | 8 | 807 | 95 | 47, 191 |

| 1999 | 154 | 173 | 9 | 915 | 99 | 51, 182 |

| 2000 | 148 | 164 | 7 | 787 | 95 | 45, 181 |

| 2001 | 147 | 162 | 8 | 865 | 99 | 49, 168 |

| 2002 | 144 | 160 | 6 | 809 | 93 | 45, 165 |

N = 96 metropolitan statistical areas

SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range

Figure 1.

Average population prevalence of injection drug users by racial/ethnic group and year, 1992–2002. N = 96 metropolitan statistical areas. Data for non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black IDUs were previously published9 and exclude the San Juan, Puerto Rico MSA.

Yearly Pearson correlations with drug-related mortality rates and hepatitis C mortality rates among Hispanics are in Table 3. Correlations with drug-related mortality ranged from 0.36 to 0.62 (mean = 0.48). Correlations with hepatitis C mortality ranged from 0.43 to 0.73 (mean = 0.58).

Table 3.

Pearson correlations of estimated Hispanic injection drug user population prevalence rates with mortality rates for drug-related deaths and hepatitis C deaths among Hispanics, 1992–2002

| Drug-related mortality | Hepatitis C mortality | |

|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 0.56 | – |

| 1993 | 0.62 | – |

| 1994 | 0.47 | – |

| 1995 | 0.36 | – |

| 1996 | 0.45 | – |

| 1997 | 0.54 | – |

| 1998 | 0.54 | – |

| 1999 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| 2000 | 0.42 | 0.43 |

| 2001 | 0.40 | 0.73 |

| 2002 | 0.41 | 0.66 |

N = 96 metropolitan statistical areas

Results of the polynomial mixed-effects model testing for trend over time in logged Hispanic IDU population prevalence rates are in Table 4. The antilog of the intercept, representing Hispanic IDU population prevalence in 1992, is 132.4 Hispanic IDUs per 10,000 Hispanics. The average annual logged linear decline is −0.070; however, the positive polynomial term (0.0028) indicates a flattening of the slope over time. The antilog of the average year-to-year decline, including linear and quadratic terms, was 8.6 per 10,000 from 1992 to 1993 but lessened to 1.4 per 10,000 from 2001 to 2002. The predicted value for 2002 is 87.1 per 10,000, which approximates the observed median estimate.

Table 4.

Linear mixed-effects regression results of logged Hispanic injection drug user population prevalence, 1992–2002

| Estimate | Standard error | |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||

| Intercept | 4.8857* | 0.0885 |

| Years since 1992 | −0.0702* | 0.0061 |

| Years since 1992 squared | 0.0028* | 0.0004 |

| Random effects | ||

| Intercept variance | 0.7486 | 0.1091 |

| Years since 1992 variance | 0.0028 | 0.000545 |

| Years since 1992 squared variance | 0.00468 | 0.001968 |

| Residual variance | 0.00664 | 0.000380 |

N = 96 metropolitan statistical areas

*p < 0.01

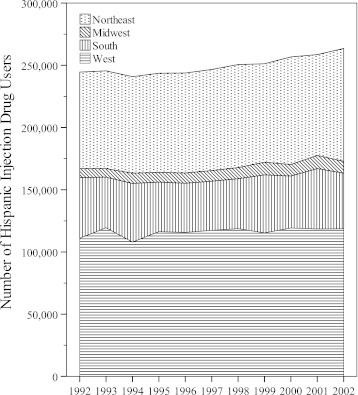

The sum of the number of Hispanic IDUs in these MSAs by Census region is presented in Figure 2. An increase in the most recent years of the study period is evident for the northeast region, with less change in the other regions.

Figure 2.

Sum of Hispanic injection drug users by Census region and year, 1992–2002. N = 96 metropolitan statistical areas.

MSA-specific results are presented in the Appendix. The largest populations of Hispanic IDUs were generally in the MSAs most populated by Hispanics. Averaging the most recent 3 years (2000–2002), the five MSAs with the largest Hispanic IDU populations were Los Angeles–Long Beach, CA (40,375); New York, NY (36,999); San Juan–Bayamon, PR (15,333); Boston, MA–NH (9,872); and San Antonio, TX (9,266). However, the highest IDU prevalence rates among Hispanic residents tended to be in smaller northeastern MSAs. Averaging the most recent 3 years, the five MSAs with the highest prevalence rates (per 10,000 Hispanic residents) were Allentown–Bethlehem–Easton, PA (756); Springfield, MA (752); Hartford, CT (694); Harrisburg–Lebanon–Carlisle, PA (652); and Buffalo–Niagara Falls, NY (533).

We calculated percent change values comparing averages of the earliest (1992–1994) and latest (2000–2002) 3 years of data. Hispanic IDU population prevalence decreased in 79 MSAs—by 10% or more in 70 MSAs and by 50% or more in 13 MSAs. Prevalence increased in 17 MSAs—by 10% or more in eight MSAs (Boston, MA–NH 38%; Baltimore, MD 35%; Honolulu, HI 25%; Toledo, OH and Stockton–Lodi, CA 14%; Pittsburgh, PA and Springfield, MA 12%) and by 50% or more in one MSA (Youngstown–Warren, OH 64%).

Lastly, to extend the analysis to more recent years, for which overall IDU prevalence has not been published, we compared the proportion of IDUs that was Hispanic between 2003 and 2007. This proportion did not change significantly between 2003 and 2007 (linear estimate [Est.] = −0.0057, standard error [SE] = 0.1158; quadratic Est. = 0.0004, SE = 0.0046) across MSAs. We then compared change in the proportion averaged over 2002–2004 to the proportion averaged over 2005–2007 (change could not be estimated for four MSAs with missing data—Gary, IN; San Juan–Bayamon, PR; Tucson, AZ; and Wichita, KS). Of the remaining 92 MSAs, the proportion of IDUs that was Hispanic decreased in 42 (52%) and increased in 44 (48%). Of these 44, 19 increased by more than 10%, and 13 increased by more than 20% (Dayton–Springfield, OH 60%; Greenville–Spartanburg–Anderson, SC 53%; Las Vegas, NV–AZ 49%; New Orleans, LA 45%; Norfolk–Virginia Beach–Newport News, VA–NC 39%; Atlanta, GA 37%; Little Rock–North Little Rock, AR 33%; Richmond–Petersburg, VA 32%; St. Louis, MO–IL 29%; Baltimore, MD 26%; Tacoma, WA 23%; Jacksonville, FL 23%; Detroit, MI 22%).

Discussion

Results from this study greatly expand the data available on Hispanic IDUs in the USA. Multiple sources of data on the proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic showed consistency, and comparisons with data on drug-related mortality and hepatitis C mortality supported the validity of the estimates. Hispanic IDU population prevalence declined from the early 1990s to the early 2000s in most MSAs. This is evident both in trend tests on mean values, in inspection of median and interquartile range values, and in comparisons of early versus late study years within MSAs. A substantial decline in IDU prevalence was previously observed among African American residents of these MSAs on average during this period, while IDU prevalence among non-Hispanic Whites was little changed.9,23 The decline in Hispanic IDU prevalence is similar to the decline in overall IDU prevalence during this time period.8 Mortality from AIDS, overdose, and other causes is likely to have contributed to the reduction in IDU prevalence among Hispanics, just as these causes are likely to have contributed to the reduction in IDU prevalence overall. In addition, the increase in heroin purity, as well as increasing consumption of prescription opioids, may have contributed to the reduction in injecting as a form of drug consumption during this time period.24,25

MSAs with the highest Hispanic IDU prevalence in the years from which the most recent data were available tended to be in the northeast. The ten MSAs with the highest Hispanic IDU prevalence in 2000–2002 were all in Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, or Connecticut. However, MSAs with increasing prevalence were dispersed geographically. MSAs with the largest Hispanic IDU populations across time were also dispersed geographically in MSAs with the largest overall Hispanic populations. More recent data on the proportions of IDUs who were Hispanic showed increases in almost half of the MSAs studied. Research is needed to determine if these increases have translated into increases in Hispanic IDU prevalence and if more recent prevalence trends differ by region.

The extent to which these findings are applicable among Hispanic national origin subgroups is unclear. For example, AIDS cases have been attributed to injecting drugs at a higher proportion among Puerto Rican-born Hispanics than among Hispanics born in the mainland USA or in other countries.26–28 According to national treatment data, Puerto Rican clients more often report using opiates than other Hispanic clients on admission,29 and IDUs in Puerto Rico are less likely to utilize drug treatment services than Puerto Rican IDUs in the mainland.30 In addition, injection drug use and risk behaviors have been reported to be more prevalent among Hispanics of Puerto Rican decent, particularly among those born in Puerto Rico, than among Hispanics with origins in Mexico and other countries.31–33 Conversely, risk reduction practices have been found to be more frequently reported among Hispanic IDUs of US or Puerto Rican origin than among Hispanics of Mexican origin (particularly those residing in border areas) or other national origin.31,34 Comparing trends in drug use and HIV among Hispanic subgroups in the USA is complicated by the dearth of health data with detailed information regarding national origin and by the large number and diversity of national origin subgroups. Although data on AIDS diagnoses show the distribution of AIDS cases among US Hispanic IDUs by national origin, the lack of population denominators precludes the calculation of prevalence or incidence by national origin, either nationally or by MSA.26 There may also be differences in interpreting survey questions regarding drug use based on national differences in language and stigma regarding drug use that could bias existing data.35

Research is needed to understand the determinants of IDU prevalence trends among Hispanics in these MSAs. Although the overall trend in Hispanic IDU prevalence was downward, prevalence increased in 17 MSAs when comparing early and late study years. It is also important to note that the total population of Hispanic IDUs in these MSAs increased in later study years, as can be seen in Figure 2. The study period corresponds with a substantial increase in the Hispanic population in the USA. Between 1990 and 2000, the US Hispanic population increased by 57.9%, representing almost 13 million new Hispanic residents.36 Hispanic immigration trends may have masked underlying trends in IDU prevalence among non-immigrant Hispanic populations. Our findings may actually conflate increases in non-immigrant (including Puerto Rican) Hispanic IDU prevalence offset by increases in Hispanic immigrant populations, who may be less likely to inject drugs.37,38

Results of the present study are consistent with results from our cross-sectional study that found little difference in IDU prevalence between Hispanic and non-Hispanic White MSA residents in 1998.39 Although the mean prevalence rates differ, as can be seen in Figure 1, the 1998 median prevalence rates among Hispanic (95 per 10,000) and non-Hispanic White (93 per 10,000)39 MSA residents are quite similar. IDU prevalence appears to have differed more greatly between Hispanic and non-Hispanic White MSA residents during earlier study years (1992–1997).

Limitations

The data were subject to several limitations. Injection drug use among Hispanics varies by national origin subgroup and immigrant or non-immigrant status, but only limited data on these characteristics were available. Hispanic immigrant IDUs, especially those with undocumented status, may avoid participating in the US Census, HIV testing, and/or utilizing drug treatment services.

CTS and TEDS data may underrepresent Hispanic IDUs because they may be less likely to utilize HIV testing and drug treatment services.6,7 This bias may be somewhat balanced by the likelihood that IAIDS data overrepresents Hispanics, as a result of their greater likelihood to progress to AIDS, once HIV-infected40; however, there are few data available to test this. CTS data represent only a small proportion of all HIV tests done in the USA and can include results for individuals tested more than once. Thus, they are an imperfect proxy for HIV prevalence among IDUs. In addition, changes in the completeness of reporting of CTS, TEDS, or IAIDS data over time may have biased the results.

While we adjusted IAIDS data for the proportions of IDUs who tested positive for HIV, we could not adjust for relative progression to AIDS or mortality, and those potential differences could have biased our IAIDS data. Further, average pseudo-likelihood HIV prevalence values were used in 22 MSAs where MSA-specific HIV test result values were missing. These values may not have represented the actual HIV prevalence well in some of those MSAs.

Conclusion

Estimates of IDU population prevalence among Hispanic residents of large MSAs showed a significant decline between 1992 and 2002; however, prevalence estimates increased in a substantial proportion of MSAs, and the proportion of IDUs that was Hispanic increased between 2002 and 2007 in almost half of the MSAs studied. These estimates can be used to study MSA-level policies and socioeconomic factors that may account for variations in trends across MSAs and across racial/ethnic groups and can be used to help guide prevention program planning for Hispanic IDUs within MSAs. Future research should also attempt to determine reasons for any differences in trends that might exist among Hispanic national origin subgroups and among immigrant and non-immigrant Hispanics.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA018609). The authors would also like to acknowledge the NIH-funded Center for Drug Use and HIV Research (P30 DA121041) for its support and assistance.

Appendix

Table 5.

MSA-specific estimates of the number of Hispanic injection drug users and population prevalence rate of injection drug users among Hispanics (per 10,000 Hispanics aged 15–64), with 95 % confidence intervals, 1992–2002. N = the 96 most populated US metropolitan statistical areas

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Akron, OH | 1992 | 27 | 9 | 79 | 99 | 33 | 289 |

| 1993 | 24 | 8 | 72 | 84 | 28 | 251 | |

| 1994 | 29 | 10 | 85 | 98 | 34 | 287 | |

| 1995 | 26 | 9 | 78 | 84 | 29 | 251 | |

| 1996 | 28 | 9 | 82 | 86 | 28 | 252 | |

| 1997 | 29 | 10 | 85 | 86 | 30 | 252 | |

| 1998 | 30 | 10 | 89 | 86 | 29 | 256 | |

| 1999 | 37 | 12 | 108 | 102 | 33 | 297 | |

| 2000 | 34 | 11 | 100 | 89 | 29 | 261 | |

| 2001 | 41 | 14 | 122 | 102 | 35 | 302 | |

| 2002 | 39 | 13 | 114 | 92 | 31 | 270 | |

| Albany–Schenectady–Troy, NY | 1992 | 647 | 266 | 1,410 | 589 | 242 | 1,284 |

| 1993 | 576 | 238 | 1,252 | 502 | 207 | 1,091 | |

| 1994 | 594 | 245 | 1,287 | 495 | 204 | 1,074 | |

| 1995 | 551 | 228 | 1,190 | 440 | 182 | 951 | |

| 1996 | 548 | 227 | 1,178 | 422 | 175 | 906 | |

| 1997 | 536 | 223 | 1,147 | 395 | 164 | 846 | |

| 1998 | 558 | 233 | 1,188 | 396 | 165 | 843 | |

| 1999 | 538 | 225 | 1,140 | 368 | 154 | 779 | |

| 2000 | 630 | 264 | 1,327 | 409 | 171 | 862 | |

| 2001 | 572 | 241 | 1,197 | 356 | 150 | 745 | |

| 2002 | 737 | 311 | 1,533 | 435 | 184 | 905 | |

| Albuquerque, NM | 1992 | 5,093 | 2,788 | 7,412 | 333 | 182 | 484 |

| 1993 | 4,807 | 2,641 | 6,973 | 305 | 167 | 442 | |

| 1994 | 5,121 | 2,824 | 7,401 | 312 | 172 | 451 | |

| 1995 | 4,889 | 2,707 | 7,037 | 287 | 159 | 413 | |

| 1996 | 4,864 | 2,706 | 6,971 | 276 | 153 | 395 | |

| 1997 | 4,839 | 2,705 | 6,901 | 268 | 150 | 383 | |

| 1998 | 4,877 | 2,742 | 6,919 | 264 | 148 | 374 | |

| 1999 | 5,073 | 2,870 | 7,156 | 268 | 152 | 379 | |

| 2000 | 4,988 | 2,840 | 6,996 | 256 | 146 | 359 | |

| 2001 | 5,232 | 3,000 | 7,293 | 261 | 150 | 364 | |

| 2002 | 5,185 | 2,993 | 7,182 | 251 | 145 | 348 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Allentown–Bethlehem–Easton, PA | 1992 | 2,038 | 952 | 3,591 | 1,068 | 499 | 1,881 |

| 1993 | 1,879 | 880 | 3,300 | 924 | 433 | 1,622 | |

| 1994 | 2,315 | 1,087 | 4,048 | 1,070 | 502 | 1,871 | |

| 1995 | 2,088 | 984 | 3,635 | 905 | 426 | 1,575 | |

| 1996 | 2,168 | 1,025 | 3,756 | 874 | 413 | 1,514 | |

| 1997 | 2,224 | 1,056 | 3,832 | 840 | 399 | 1,447 | |

| 1998 | 2,272 | 1,084 | 3,892 | 807 | 385 | 1,382 | |

| 1999 | 2,744 | 1,316 | 4,671 | 915 | 439 | 1,558 | |

| 2000 | 2,305 | 1,111 | 3,897 | 725 | 350 | 1,226 | |

| 2001 | 2,886 | 1,399 | 4,844 | 865 | 419 | 1,451 | |

| 2002 | 2,403 | 1,171 | 4,004 | 679 | 331 | 1,131 | |

| Ann Arbor, MI | 1992 | 19 | 6 | 57 | 21 | 7 | 64 |

| 1993 | 19 | 6 | 55 | 21 | 7 | 61 | |

| 1994 | 19 | 6 | 57 | 20 | 6 | 61 | |

| 1995 | 20 | 7 | 59 | 20 | 7 | 60 | |

| 1996 | 20 | 7 | 59 | 19 | 7 | 57 | |

| 1997 | 21 | 7 | 62 | 19 | 6 | 57 | |

| 1998 | 22 | 7 | 66 | 20 | 6 | 59 | |

| 1999 | 23 | 8 | 67 | 20 | 7 | 57 | |

| 2000 | 25 | 8 | 72 | 20 | 6 | 58 | |

| 2001 | 26 | 9 | 76 | 20 | 7 | 59 | |

| 2002 | 28 | 9 | 82 | 21 | 7 | 61 | |

| Atlanta, GA | 1992 | 244 | 86 | 680 | 42 | 15 | 118 |

| 1993 | 229 | 81 | 638 | 34 | 12 | 96 | |

| 1994 | 244 | 86 | 681 | 31 | 11 | 88 | |

| 1995 | 228 | 81 | 636 | 25 | 9 | 68 | |

| 1996 | 228 | 81 | 635 | 21 | 7 | 58 | |

| 1997 | 228 | 81 | 634 | 17 | 6 | 48 | |

| 1998 | 227 | 80 | 631 | 15 | 5 | 42 | |

| 1999 | 240 | 85 | 668 | 14 | 5 | 38 | |

| 2000 | 220 | 78 | 611 | 11 | 4 | 31 | |

| 2001 | 236 | 84 | 655 | 11 | 4 | 30 | |

| 2002 | 205 | 73 | 570 | 9 | 3 | 25 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Austin–San Marcos, TX | 1992 | 3,708 | 1,611 | 7,330 | 278 | 121 | 550 |

| 1993 | 3,403 | 1,481 | 6,702 | 239 | 104 | 470 | |

| 1994 | 4,068 | 1,775 | 7,982 | 267 | 117 | 525 | |

| 1995 | 3,647 | 1,595 | 7,128 | 223 | 98 | 436 | |

| 1996 | 3,639 | 1,596 | 7,079 | 209 | 92 | 406 | |

| 1997 | 3,493 | 1,537 | 6,761 | 188 | 83 | 365 | |

| 1998 | 3,341 | 1,476 | 6,430 | 169 | 75 | 325 | |

| 1999 | 3,697 | 1,640 | 7,073 | 175 | 78 | 334 | |

| 2000 | 3,111 | 1,386 | 5,912 | 136 | 61 | 259 | |

| 2001 | 3,328 | 1,489 | 6,281 | 137 | 61 | 259 | |

| 2002 | 2,710 | 1,218 | 5,080 | 107 | 48 | 201 | |

| Bakersfield, CA | 1992 | 2,713 | 1,173 | 5,405 | 252 | 109 | 502 |

| 1993 | 2,543 | 1,102 | 5,048 | 225 | 97 | 447 | |

| 1994 | 2,790 | 1,211 | 5,518 | 231 | 100 | 457 | |

| 1995 | 2,641 | 1,150 | 5,203 | 211 | 92 | 416 | |

| 1996 | 2,668 | 1,165 | 5,232 | 205 | 89 | 402 | |

| 1997 | 2,738 | 1,199 | 5,341 | 200 | 88 | 391 | |

| 1998 | 2,765 | 1,215 | 5,364 | 192 | 84 | 373 | |

| 1999 | 3,099 | 1,368 | 5,977 | 204 | 90 | 393 | |

| 2000 | 2,858 | 1,266 | 5,475 | 181 | 80 | 346 | |

| 2001 | 3,186 | 1,418 | 6,063 | 193 | 86 | 368 | |

| 2002 | 2,960 | 1,323 | 5,594 | 171 | 76 | 323 | |

| Baltimore, MD | 1992 | 160 | 58 | 441 | 69 | 25 | 191 |

| 1993 | 195 | 70 | 539 | 80 | 29 | 221 | |

| 1994 | 200 | 72 | 551 | 77 | 28 | 213 | |

| 1995 | 227 | 82 | 627 | 84 | 30 | 232 | |

| 1996 | 246 | 88 | 678 | 87 | 31 | 239 | |

| 1997 | 266 | 96 | 734 | 88 | 32 | 244 | |

| 1998 | 291 | 105 | 801 | 92 | 33 | 252 | |

| 1999 | 327 | 118 | 901 | 97 | 35 | 268 | |

| 2000 | 352 | 127 | 968 | 98 | 35 | 270 | |

| 2001 | 396 | 143 | 1,089 | 104 | 37 | 285 | |

| 2002 | 424 | 153 | 1,168 | 104 | 37 | 286 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Bergen–Passaic, NJ | 1992 | 1,781 | 755 | 3,676 | 149 | 63 | 308 |

| 1993 | 1,785 | 758 | 3,671 | 143 | 61 | 293 | |

| 1994 | 1,680 | 715 | 3,444 | 129 | 55 | 264 | |

| 1995 | 1,654 | 706 | 3,376 | 121 | 52 | 248 | |

| 1996 | 1,593 | 681 | 3,238 | 112 | 48 | 227 | |

| 1997 | 1,554 | 667 | 3,143 | 104 | 45 | 210 | |

| 1998 | 1,551 | 668 | 3,120 | 100 | 43 | 200 | |

| 1999 | 1,586 | 685 | 3,173 | 98 | 42 | 197 | |

| 2000 | 1,606 | 697 | 3,192 | 96 | 42 | 191 | |

| 2001 | 1,586 | 691 | 3,133 | 91 | 40 | 181 | |

| 2002 | 1,676 | 733 | 3,288 | 94 | 41 | 183 | |

| Birmingham, AL | 1992 | 7 | 2 | 25 | 21 | 6 | 76 |

| 1993 | 6 | 2 | 22 | 16 | 5 | 58 | |

| 1994 | 7 | 2 | 27 | 16 | 4 | 60 | |

| 1995 | 6 | 2 | 23 | 11 | 4 | 44 | |

| 1996 | 7 | 2 | 24 | 11 | 3 | 38 | |

| 1997 | 7 | 2 | 24 | 9 | 3 | 32 | |

| 1998 | 7 | 2 | 25 | 8 | 2 | 28 | |

| 1999 | 9 | 3 | 32 | 9 | 3 | 30 | |

| 2000 | 8 | 2 | 27 | 7 | 2 | 23 | |

| 2001 | 10 | 3 | 34 | 8 | 2 | 27 | |

| 2002 | 8 | 2 | 30 | 6 | 1 | 22 | |

| Boston, MA–NH | 1992 | 4,260 | 1,733 | 9,552 | 250 | 102 | 560 |

| 1993 | 5,904 | 2,406 | 13,201 | 332 | 135 | 743 | |

| 1994 | 4,797 | 1,957 | 10,693 | 260 | 106 | 579 | |

| 1995 | 6,865 | 2,806 | 15,255 | 354 | 145 | 787 | |

| 1996 | 7,398 | 3,030 | 16,378 | 365 | 149 | 807 | |

| 1997 | 8,112 | 3,330 | 17,884 | 382 | 157 | 843 | |

| 1998 | 8,798 | 3,621 | 19,306 | 395 | 163 | 867 | |

| 1999 | 6,694 | 2,763 | 14,614 | 287 | 118 | 627 | |

| 2000 | 10,207 | 4,227 | 22,161 | 419 | 174 | 911 | |

| 2001 | 7,619 | 3,165 | 16,447 | 298 | 124 | 642 | |

| 2002 | 11,791 | 4,912 | 25,310 | 443 | 184 | 950 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Lower limit | ||||

| Buffalo–Niagara Falls, NY | 1992 | 860 | 354 | 1,875 | 526 | 217 | 1,148 |

| 1993 | 1,037 | 428 | 2,253 | 610 | 252 | 1,326 | |

| 1994 | 941 | 389 | 2,040 | 532 | 220 | 1,152 | |

| 1995 | 1,096 | 454 | 2,365 | 600 | 249 | 1,295 | |

| 1996 | 1,123 | 466 | 2,415 | 591 | 245 | 1,272 | |

| 1997 | 1,137 | 473 | 2,434 | 584 | 243 | 1,250 | |

| 1998 | 1,155 | 482 | 2,461 | 577 | 241 | 1,229 | |

| 1999 | 1,035 | 433 | 2,193 | 504 | 211 | 1,068 | |

| 2000 | 1,183 | 497 | 2,493 | 561 | 236 | 1,183 | |

| 2001 | 1,038 | 438 | 2,174 | 480 | 203 | 1,005 | |

| 2002 | 1,235 | 522 | 2,570 | 557 | 236 | 1,160 | |

| Charleston–North Charleston, SC | 1992 | 32 | 10 | 97 | 55 | 17 | 167 |

| 1993 | 25 | 8 | 77 | 43 | 14 | 132 | |

| 1994 | 28 | 9 | 86 | 47 | 15 | 146 | |

| 1995 | 23 | 7 | 70 | 37 | 11 | 112 | |

| 1996 | 22 | 7 | 67 | 34 | 11 | 103 | |

| 1997 | 24 | 8 | 72 | 33 | 11 | 98 | |

| 1998 | 25 | 8 | 77 | 31 | 10 | 95 | |

| 1999 | 30 | 10 | 91 | 33 | 11 | 101 | |

| 2000 | 27 | 9 | 83 | 28 | 9 | 87 | |

| 2001 | 31 | 10 | 94 | 31 | 10 | 95 | |

| 2002 | 29 | 9 | 88 | 28 | 9 | 86 | |

| Charlotte–Gastonia–Rock Hill, NC–SC | 1992 | 49 | 17 | 146 | 44 | 15 | 131 |

| 1993 | 42 | 14 | 123 | 31 | 10 | 92 | |

| 1994 | 49 | 16 | 144 | 29 | 10 | 86 | |

| 1995 | 44 | 15 | 129 | 21 | 7 | 63 | |

| 1996 | 45 | 15 | 131 | 17 | 6 | 51 | |

| 1997 | 45 | 15 | 134 | 14 | 5 | 42 | |

| 1998 | 46 | 16 | 136 | 12 | 4 | 34 | |

| 1999 | 54 | 18 | 160 | 11 | 4 | 33 | |

| 2000 | 49 | 17 | 144 | 9 | 3 | 25 | |

| 2001 | 59 | 20 | 174 | 9 | 3 | 28 | |

| 2002 | 51 | 17 | 149 | 8 | 3 | 22 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Chicago, IL | 1992 | 4,103 | 1,628 | 9,696 | 66 | 26 | 157 |

| 1993 | 3,618 | 1,437 | 8,530 | 55 | 22 | 131 | |

| 1994 | 4,184 | 1,664 | 9,839 | 61 | 24 | 143 | |

| 1995 | 3,676 | 1,464 | 8,622 | 51 | 20 | 119 | |

| 1996 | 3,715 | 1,482 | 8,685 | 48 | 19 | 113 | |

| 1997 | 3,692 | 1,475 | 8,601 | 46 | 18 | 106 | |

| 1998 | 3,813 | 1,527 | 8,847 | 45 | 18 | 103 | |

| 1999 | 4,558 | 1,830 | 10,527 | 51 | 20 | 117 | |

| 2000 | 4,000 | 1,610 | 9,195 | 42 | 17 | 97 | |

| 2001 | 4,958 | 2,001 | 11,343 | 51 | 20 | 116 | |

| 2002 | 4,372 | 1,768 | 9,952 | 43 | 18 | 99 | |

| Cincinnati, OH–KY–IN | 1992 | 79 | 26 | 233 | 128 | 42 | 377 |

| 1993 | 66 | 22 | 195 | 98 | 33 | 290 | |

| 1994 | 78 | 26 | 229 | 108 | 36 | 317 | |

| 1995 | 65 | 22 | 192 | 84 | 28 | 248 | |

| 1996 | 65 | 22 | 191 | 77 | 26 | 227 | |

| 1997 | 66 | 22 | 193 | 73 | 24 | 212 | |

| 1998 | 68 | 23 | 200 | 68 | 23 | 201 | |

| 1999 | 85 | 29 | 251 | 79 | 27 | 232 | |

| 2000 | 76 | 26 | 224 | 63 | 21 | 185 | |

| 2001 | 96 | 32 | 281 | 73 | 24 | 215 | |

| 2002 | 85 | 28 | 249 | 61 | 20 | 179 | |

| Cleveland–Lorain–Elyria, OH | 1992 | 1,421 | 565 | 3,327 | 410 | 163 | 961 |

| 1993 | 1,251 | 498 | 2,922 | 345 | 137 | 805 | |

| 1994 | 1,447 | 577 | 3,371 | 385 | 153 | 897 | |

| 1995 | 1,294 | 517 | 3,005 | 330 | 132 | 766 | |

| 1996 | 1,318 | 528 | 3,053 | 323 | 129 | 747 | |

| 1997 | 1,342 | 538 | 3,096 | 318 | 128 | 734 | |

| 1998 | 1,368 | 550 | 3,143 | 313 | 126 | 719 | |

| 1999 | 1,570 | 632 | 3,590 | 347 | 140 | 794 | |

| 2000 | 1,467 | 593 | 3,339 | 311 | 126 | 708 | |

| 2001 | 1,672 | 677 | 3,786 | 343 | 139 | 776 | |

| 2002 | 1,572 | 638 | 3,543 | 313 | 127 | 705 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Columbus, OH | 1992 | 120 | 42 | 339 | 126 | 44 | 356 |

| 1993 | 111 | 39 | 313 | 105 | 37 | 297 | |

| 1994 | 131 | 46 | 369 | 115 | 40 | 323 | |

| 1995 | 119 | 42 | 335 | 95 | 33 | 267 | |

| 1996 | 123 | 43 | 344 | 89 | 31 | 250 | |

| 1997 | 127 | 44 | 355 | 84 | 29 | 236 | |

| 1998 | 133 | 47 | 373 | 81 | 28 | 226 | |

| 1999 | 159 | 56 | 446 | 88 | 31 | 246 | |

| 2000 | 149 | 52 | 416 | 74 | 26 | 208 | |

| 2001 | 182 | 64 | 509 | 83 | 29 | 232 | |

| 2002 | 173 | 60 | 482 | 74 | 26 | 206 | |

| Dallas, TX | 1992 | 1,868 | 720 | 4,709 | 64 | 25 | 161 |

| 1993 | 1,596 | 616 | 4,016 | 50 | 19 | 127 | |

| 1994 | 2,014 | 777 | 5,056 | 59 | 23 | 148 | |

| 1995 | 1,815 | 701 | 4,549 | 49 | 19 | 123 | |

| 1996 | 1,919 | 742 | 4,797 | 48 | 18 | 119 | |

| 1997 | 2,060 | 798 | 5,136 | 47 | 18 | 118 | |

| 1998 | 2,213 | 858 | 5,498 | 47 | 18 | 116 | |

| 1999 | 2,769 | 1,076 | 6,857 | 54 | 21 | 134 | |

| 2000 | 2,523 | 982 | 6,226 | 46 | 18 | 114 | |

| 2001 | 3,278 | 1,278 | 8,059 | 56 | 22 | 138 | |

| 2002 | 2,882 | 1,125 | 7,060 | 47 | 18 | 114 | |

| Dayton–Springfield, OH | 1992 | 12 | 4 | 39 | 23 | 8 | 73 |

| 1993 | 11 | 3 | 34 | 20 | 5 | 61 | |

| 1994 | 12 | 4 | 37 | 21 | 7 | 64 | |

| 1995 | 10 | 3 | 32 | 17 | 5 | 53 | |

| 1996 | 10 | 3 | 32 | 16 | 5 | 51 | |

| 1997 | 10 | 3 | 32 | 15 | 5 | 49 | |

| 1998 | 11 | 3 | 34 | 16 | 4 | 50 | |

| 1999 | 13 | 4 | 40 | 18 | 6 | 56 | |

| 2000 | 13 | 4 | 41 | 17 | 5 | 54 | |

| 2001 | 16 | 5 | 49 | 20 | 6 | 62 | |

| 2002 | 16 | 5 | 50 | 19 | 6 | 60 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Denver, CO | 1992 | 5,008 | 2,166 | 9,975 | 318 | 137 | 633 |

| 1993 | 4,556 | 1,975 | 9,043 | 268 | 116 | 532 | |

| 1994 | 4,853 | 2,108 | 9,598 | 269 | 117 | 532 | |

| 1995 | 4,934 | 2,149 | 9,718 | 256 | 112 | 504 | |

| 1996 | 5,172 | 2,259 | 10,141 | 251 | 110 | 492 | |

| 1997 | 5,429 | 2,378 | 10,591 | 247 | 108 | 481 | |

| 1998 | 5,681 | 2,498 | 11,021 | 243 | 107 | 472 | |

| 1999 | 4,547 | 2,007 | 8,767 | 182 | 80 | 351 | |

| 2000 | 5,717 | 2,535 | 10,952 | 216 | 96 | 414 | |

| 2001 | 4,504 | 2,006 | 8,571 | 161 | 72 | 307 | |

| 2002 | 5,666 | 2,534 | 10,706 | 195 | 87 | 368 | |

| Detroit, MI | 1992 | 403 | 149 | 1,124 | 69 | 25 | 191 |

| 1993 | 425 | 158 | 1,183 | 70 | 26 | 194 | |

| 1994 | 418 | 155 | 1,162 | 66 | 25 | 184 | |

| 1995 | 465 | 172 | 1,292 | 70 | 26 | 195 | |

| 1996 | 493 | 183 | 1,370 | 70 | 26 | 195 | |

| 1997 | 515 | 191 | 1,429 | 70 | 26 | 195 | |

| 1998 | 532 | 198 | 1,474 | 70 | 26 | 193 | |

| 1999 | 469 | 175 | 1,299 | 59 | 22 | 164 | |

| 2000 | 555 | 206 | 1,533 | 67 | 25 | 185 | |

| 2001 | 481 | 179 | 1,329 | 55 | 21 | 153 | |

| 2002 | 586 | 218 | 1,616 | 65 | 24 | 179 | |

| El Paso, TX | 1992 | 10,476 | 7,374 | 12,461 | 372 | 262 | 443 |

| 1993 | 8,651 | 6,110 | 10,270 | 297 | 210 | 352 | |

| 1994 | 9,862 | 6,989 | 11,682 | 328 | 232 | 388 | |

| 1995 | 8,004 | 5,694 | 9,457 | 260 | 185 | 307 | |

| 1996 | 7,564 | 5,404 | 8,914 | 242 | 173 | 285 | |

| 1997 | 7,363 | 5,285 | 8,653 | 230 | 165 | 271 | |

| 1998 | 6,930 | 4,999 | 8,119 | 213 | 153 | 249 | |

| 1999 | 7,397 | 5,365 | 8,638 | 224 | 162 | 261 | |

| 2000 | 6,104 | 4,452 | 7,104 | 181 | 132 | 211 | |

| 2001 | 5,966 | 4,378 | 6,920 | 175 | 128 | 203 | |

| 2002 | 5,243 | 3,870 | 6,059 | 152 | 112 | 176 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Fort Lauderdale, FL | 1992 | 686 | 264 | 1,722 | 74 | 29 | 186 |

| 1993 | 574 | 221 | 1,437 | 56 | 22 | 140 | |

| 1994 | 697 | 269 | 1,744 | 62 | 24 | 155 | |

| 1995 | 585 | 226 | 1,460 | 47 | 18 | 118 | |

| 1996 | 597 | 231 | 1,487 | 44 | 17 | 109 | |

| 1997 | 615 | 238 | 1,526 | 41 | 16 | 102 | |

| 1998 | 631 | 245 | 1,562 | 39 | 15 | 96 | |

| 1999 | 769 | 299 | 1,897 | 43 | 17 | 107 | |

| 2000 | 663 | 258 | 1,628 | 34 | 13 | 84 | |

| 2001 | 814 | 317 | 1,992 | 39 | 15 | 95 | |

| 2002 | 692 | 270 | 1,688 | 31 | 12 | 74 | |

| Fort Worth–Arlington, TX | 1992 | 1,957 | 760 | 4,850 | 170 | 66 | 422 |

| 1993 | 1,647 | 640 | 4,073 | 134 | 52 | 332 | |

| 1994 | 2,006 | 781 | 4,951 | 152 | 59 | 376 | |

| 1995 | 1,732 | 675 | 4,266 | 122 | 48 | 301 | |

| 1996 | 1,774 | 692 | 4,358 | 116 | 45 | 285 | |

| 1997 | 1,820 | 711 | 4,457 | 110 | 43 | 270 | |

| 1998 | 1,859 | 727 | 4,538 | 105 | 41 | 255 | |

| 1999 | 2,242 | 879 | 5,452 | 117 | 46 | 284 | |

| 2000 | 1,955 | 768 | 4,734 | 95 | 37 | 229 | |

| 2001 | 2,342 | 922 | 5,649 | 106 | 42 | 256 | |

| 2002 | 2,047 | 807 | 4,918 | 87 | 34 | 210 | |

| Fresno, CA | 1992 | 5,130 | 2,622 | 8,057 | 278 | 142 | 436 |

| 1993 | 7,532 | 3,863 | 11,789 | 388 | 199 | 607 | |

| 1994 | 5,865 | 3,018 | 9,143 | 289 | 149 | 451 | |

| 1995 | 7,590 | 3,921 | 11,782 | 361 | 187 | 561 | |

| 1996 | 7,784 | 4,038 | 12,024 | 354 | 184 | 547 | |

| 1997 | 8,087 | 4,216 | 12,427 | 353 | 184 | 542 | |

| 1998 | 8,430 | 4,419 | 12,881 | 354 | 186 | 541 | |

| 1999 | 9,116 | 4,807 | 13,846 | 369 | 194 | 560 | |

| 2000 | 8,857 | 4,700 | 13,366 | 345 | 183 | 521 | |

| 2001 | 9,787 | 5,226 | 14,669 | 370 | 198 | 555 | |

| 2002 | 9,010 | 4,843 | 13,412 | 329 | 177 | 489 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Gary, IN | 1992 | 304 | 110 | 777 | 95 | 34 | 242 |

| 1993 | 262 | 95 | 669 | 79 | 29 | 203 | |

| 1994 | 327 | 119 | 833 | 97 | 35 | 246 | |

| 1995 | 312 | 114 | 794 | 89 | 32 | 226 | |

| 1996 | 336 | 123 | 854 | 92 | 34 | 233 | |

| 1997 | 361 | 132 | 915 | 95 | 35 | 241 | |

| 1998 | 384 | 140 | 971 | 97 | 35 | 245 | |

| 1999 | 387 | 142 | 975 | 95 | 35 | 239 | |

| 2000 | 407 | 149 | 1,023 | 97 | 35 | 243 | |

| 2001 | 419 | 154 | 1,049 | 97 | 36 | 244 | |

| 2002 | 439 | 161 | 1,096 | 100 | 37 | 250 | |

| Grand Rapids–Muskegon–Holland, MI | 1992 | 205 | 76 | 513 | 96 | 35 | 240 |

| 1993 | 173 | 64 | 433 | 75 | 28 | 187 | |

| 1994 | 200 | 75 | 500 | 79 | 30 | 198 | |

| 1995 | 180 | 67 | 451 | 65 | 24 | 162 | |

| 1996 | 183 | 68 | 456 | 59 | 22 | 148 | |

| 1997 | 185 | 69 | 460 | 55 | 20 | 136 | |

| 1998 | 197 | 74 | 488 | 53 | 20 | 132 | |

| 1999 | 215 | 81 | 532 | 53 | 20 | 131 | |

| 2000 | 218 | 82 | 539 | 50 | 19 | 122 | |

| 2001 | 234 | 88 | 575 | 50 | 19 | 123 | |

| 2002 | 243 | 91 | 596 | 50 | 19 | 122 | |

| Greensboro–Winston–Salem–High Point, NC | 1992 | 50 | 17 | 152 | 62 | 21 | 190 |

| 1993 | 41 | 13 | 123 | 42 | 13 | 126 | |

| 1994 | 49 | 16 | 147 | 40 | 13 | 119 | |

| 1995 | 40 | 13 | 121 | 26 | 8 | 78 | |

| 1996 | 40 | 13 | 120 | 21 | 7 | 62 | |

| 1997 | 41 | 13 | 122 | 17 | 5 | 50 | |

| 1998 | 42 | 14 | 125 | 14 | 5 | 41 | |

| 1999 | 53 | 17 | 158 | 14 | 5 | 43 | |

| 2000 | 43 | 14 | 128 | 10 | 3 | 29 | |

| 2001 | 53 | 17 | 158 | 11 | 4 | 33 | |

| 2002 | 43 | 14 | 129 | 8 | 3 | 25 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Greenville–Spartanburg–Anderson, SC | 1992 | 30 | 9 | 91 | 54 | 16 | 164 |

| 1993 | 23 | 7 | 72 | 36 | 11 | 113 | |

| 1994 | 28 | 9 | 87 | 39 | 13 | 122 | |

| 1995 | 24 | 8 | 73 | 28 | 9 | 86 | |

| 1996 | 24 | 8 | 74 | 24 | 8 | 75 | |

| 1997 | 25 | 8 | 77 | 21 | 7 | 65 | |

| 1998 | 26 | 8 | 80 | 18 | 6 | 57 | |

| 1999 | 30 | 10 | 94 | 18 | 6 | 56 | |

| 2000 | 29 | 9 | 91 | 15 | 5 | 47 | |

| 2001 | 35 | 11 | 106 | 17 | 5 | 50 | |

| 2002 | 33 | 11 | 103 | 15 | 5 | 45 | |

| Harrisburg–Lebanon–Carlisle, PA | 1992 | 481 | 193 | 1,100 | 656 | 263 | 1,501 |

| 1993 | 451 | 181 | 1,028 | 577 | 232 | 1,316 | |

| 1994 | 568 | 225 | 1,260 | 685 | 271 | 1,519 | |

| 1995 | 532 | 211 | 1,179 | 603 | 239 | 1,337 | |

| 1996 | 604 | 239 | 1,333 | 631 | 250 | 1,393 | |

| 1997 | 713 | 283 | 1,569 | 698 | 277 | 1,537 | |

| 1998 | 819 | 326 | 1,794 | 749 | 298 | 1,641 | |

| 1999 | 1,031 | 412 | 2,248 | 887 | 355 | 1,935 | |

| 2000 | 836 | 335 | 1,813 | 678 | 272 | 1,470 | |

| 2001 | 923 | 370 | 1,991 | 717 | 288 | 1,547 | |

| 2002 | 761 | 306 | 1,633 | 561 | 226 | 1,205 | |

| Hartford, CT | 1992 | 5,073 | 2,588 | 7,978 | 968 | 494 | 1,523 |

| 1993 | 5,043 | 2,581 | 7,903 | 931 | 476 | 1,458 | |

| 1994 | 5,201 | 2,671 | 8,117 | 927 | 476 | 1,447 | |

| 1995 | 5,126 | 2,643 | 7,966 | 894 | 461 | 1,389 | |

| 1996 | 5,154 | 2,669 | 7,972 | 861 | 446 | 1,332 | |

| 1997 | 5,128 | 2,668 | 7,890 | 824 | 429 | 1,268 | |

| 1998 | 5,070 | 2,652 | 7,757 | 790 | 413 | 1,209 | |

| 1999 | 4,990 | 2,626 | 7,589 | 749 | 394 | 1,140 | |

| 2000 | 5,002 | 2,648 | 7,557 | 719 | 381 | 1,087 | |

| 2001 | 4,953 | 2,639 | 7,433 | 688 | 367 | 1,032 | |

| 2002 | 5,028 | 2,696 | 7,493 | 675 | 362 | 1,006 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Honolulu, HI | 1992 | 253 | 92 | 660 | 68 | 25 | 177 |

| 1993 | 242 | 88 | 628 | 65 | 24 | 168 | |

| 1994 | 279 | 101 | 726 | 75 | 27 | 195 | |

| 1995 | 256 | 93 | 664 | 69 | 25 | 180 | |

| 1996 | 261 | 95 | 675 | 70 | 26 | 181 | |

| 1997 | 270 | 98 | 699 | 71 | 26 | 185 | |

| 1998 | 281 | 102 | 724 | 74 | 27 | 192 | |

| 1999 | 351 | 128 | 903 | 96 | 35 | 246 | |

| 2000 | 294 | 108 | 756 | 80 | 30 | 207 | |

| 2001 | 385 | 141 | 986 | 101 | 37 | 259 | |

| 2002 | 318 | 116 | 811 | 80 | 29 | 205 | |

| Houston, TX | 1992 | 8,186 | 3,323 | 18,410 | 154 | 62 | 345 |

| 1993 | 6,399 | 2,602 | 14,352 | 113 | 46 | 255 | |

| 1994 | 8,057 | 3,281 | 18,017 | 135 | 55 | 303 | |

| 1995 | 6,339 | 2,586 | 14,129 | 101 | 41 | 225 | |

| 1996 | 6,330 | 2,587 | 14,057 | 95 | 39 | 212 | |

| 1997 | 6,386 | 2,615 | 14,122 | 91 | 37 | 201 | |

| 1998 | 6,329 | 2,599 | 13,932 | 85 | 35 | 187 | |

| 1999 | 7,807 | 3,215 | 17,098 | 99 | 41 | 216 | |

| 2000 | 6,172 | 2,550 | 13,444 | 74 | 31 | 161 | |

| 2001 | 7,533 | 3,122 | 16,316 | 86 | 36 | 186 | |

| 2002 | 5,936 | 2,467 | 12,785 | 64 | 27 | 139 | |

| Indianapolis, IN | 1992 | 134 | 46 | 382 | 132 | 45 | 376 |

| 1993 | 126 | 43 | 358 | 109 | 37 | 310 | |

| 1994 | 134 | 46 | 381 | 102 | 35 | 291 | |

| 1995 | 121 | 42 | 344 | 80 | 28 | 228 | |

| 1996 | 117 | 40 | 334 | 67 | 23 | 191 | |

| 1997 | 115 | 40 | 327 | 57 | 20 | 162 | |

| 1998 | 117 | 40 | 333 | 50 | 17 | 143 | |

| 1999 | 140 | 48 | 398 | 52 | 18 | 148 | |

| 2000 | 130 | 45 | 370 | 43 | 15 | 122 | |

| 2001 | 157 | 54 | 445 | 47 | 16 | 134 | |

| 2002 | 149 | 51 | 421 | 42 | 14 | 118 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Jacksonville, FL | 1992 | 237 | 85 | 642 | 138 | 49 | 373 |

| 1993 | 177 | 63 | 479 | 98 | 35 | 266 | |

| 1994 | 223 | 80 | 604 | 117 | 42 | 318 | |

| 1995 | 177 | 64 | 479 | 87 | 32 | 236 | |

| 1996 | 182 | 65 | 492 | 81 | 29 | 220 | |

| 1997 | 187 | 67 | 506 | 78 | 28 | 210 | |

| 1998 | 195 | 70 | 527 | 77 | 28 | 208 | |

| 1999 | 241 | 87 | 651 | 90 | 33 | 244 | |

| 2000 | 212 | 76 | 571 | 74 | 26 | 199 | |

| 2001 | 267 | 96 | 719 | 85 | 31 | 230 | |

| 2002 | 234 | 84 | 629 | 69 | 25 | 185 | |

| Jersey City, NJ | 1992 | 2,677 | 1,208 | 4,969 | 193 | 87 | 359 |

| 1993 | 2,185 | 988 | 4,040 | 154 | 70 | 284 | |

| 1994 | 2,377 | 1,078 | 4,379 | 163 | 74 | 301 | |

| 1995 | 1,935 | 880 | 3,548 | 129 | 59 | 237 | |

| 1996 | 1,806 | 824 | 3,296 | 117 | 53 | 213 | |

| 1997 | 1,674 | 767 | 3,040 | 105 | 48 | 191 | |

| 1998 | 1,617 | 744 | 2,919 | 99 | 45 | 178 | |

| 1999 | 1,807 | 835 | 3,242 | 108 | 50 | 194 | |

| 2000 | 1,758 | 817 | 3,132 | 103 | 48 | 184 | |

| 2001 | 1,943 | 907 | 3,438 | 113 | 53 | 201 | |

| 2002 | 1,983 | 930 | 3,483 | 116 | 54 | 203 | |

| Kansas City, MO–KS | 1992 | 203 | 73 | 553 | 61 | 22 | 166 |

| 1993 | 185 | 66 | 502 | 52 | 18 | 141 | |

| 1994 | 209 | 75 | 568 | 54 | 20 | 148 | |

| 1995 | 187 | 67 | 509 | 45 | 16 | 123 | |

| 1996 | 191 | 68 | 518 | 43 | 15 | 116 | |

| 1997 | 195 | 70 | 528 | 40 | 14 | 108 | |

| 1998 | 192 | 69 | 520 | 36 | 13 | 99 | |

| 1999 | 209 | 75 | 565 | 37 | 13 | 99 | |

| 2000 | 184 | 66 | 497 | 30 | 11 | 81 | |

| 2001 | 199 | 72 | 537 | 31 | 11 | 82 | |

| 2002 | 175 | 63 | 472 | 25 | 9 | 69 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Knoxville, TN | 1992 | 13 | 3 | 45 | 53 | 12 | 183 |

| 1993 | 12 | 3 | 42 | 45 | 11 | 156 | |

| 1994 | 14 | 4 | 50 | 46 | 13 | 166 | |

| 1995 | 13 | 4 | 45 | 39 | 12 | 134 | |

| 1996 | 13 | 4 | 48 | 34 | 11 | 127 | |

| 1997 | 14 | 4 | 50 | 34 | 10 | 120 | |

| 1998 | 14 | 4 | 50 | 30 | 9 | 108 | |

| 1999 | 17 | 5 | 60 | 33 | 10 | 117 | |

| 2000 | 15 | 4 | 52 | 25 | 7 | 88 | |

| 2001 | 17 | 5 | 61 | 27 | 8 | 96 | |

| 2002 | 15 | 4 | 54 | 22 | 6 | 78 | |

| Las Vegas, NV–AZ | 1992 | 1,046 | 403 | 2,634 | 136 | 52 | 342 |

| 1993 | 885 | 341 | 2,222 | 103 | 40 | 259 | |

| 1994 | 1,138 | 440 | 2,853 | 115 | 44 | 288 | |

| 1995 | 1,010 | 391 | 2,528 | 88 | 34 | 221 | |

| 1996 | 1,069 | 414 | 2,668 | 83 | 32 | 206 | |

| 1997 | 1,152 | 447 | 2,869 | 77 | 30 | 191 | |

| 1998 | 1,197 | 465 | 2,971 | 70 | 27 | 174 | |

| 1999 | 1,374 | 534 | 3,398 | 72 | 28 | 178 | |

| 2000 | 1,244 | 485 | 3,066 | 59 | 23 | 145 | |

| 2001 | 1,394 | 544 | 3,423 | 61 | 24 | 149 | |

| 2002 | 1,245 | 487 | 3,045 | 51 | 20 | 125 | |

| Little Rock–North Little Rock, AR | 1992 | 20 | 6 | 61 | 61 | 18 | 188 |

| 1993 | 17 | 5 | 53 | 46 | 14 | 144 | |

| 1994 | 20 | 6 | 61 | 48 | 14 | 147 | |

| 1995 | 18 | 6 | 55 | 37 | 12 | 114 | |

| 1996 | 18 | 6 | 56 | 31 | 10 | 96 | |

| 1997 | 19 | 6 | 58 | 30 | 9 | 91 | |

| 1998 | 19 | 6 | 60 | 27 | 9 | 85 | |

| 1999 | 21 | 7 | 65 | 27 | 9 | 83 | |

| 2000 | 19 | 6 | 61 | 22 | 7 | 71 | |

| 2001 | 21 | 7 | 67 | 23 | 8 | 74 | |

| 2002 | 19 | 6 | 60 | 20 | 6 | 62 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Los Angeles–Long Beach, CA | 1992 | 35,172 | 16,887 | 59,778 | 153 | 73 | 259 |

| 1993 | 38,308 | 18,448 | 64,866 | 163 | 79 | 276 | |

| 1994 | 34,217 | 16,529 | 57,707 | 144 | 69 | 242 | |

| 1995 | 37,321 | 18,090 | 62,662 | 155 | 75 | 260 | |

| 1996 | 37,129 | 18,066 | 62,036 | 151 | 74 | 253 | |

| 1997 | 37,625 | 18,388 | 62,526 | 149 | 73 | 248 | |

| 1998 | 38,317 | 18,818 | 63,302 | 147 | 72 | 243 | |

| 1999 | 37,282 | 18,409 | 61,201 | 139 | 69 | 228 | |

| 2000 | 39,701 | 19,717 | 64,732 | 144 | 72 | 235 | |

| 2001 | 40,338 | 20,153 | 65,309 | 143 | 71 | 232 | |

| 2002 | 41,086 | 20,645 | 66,039 | 143 | 72 | 229 | |

| Louisville, KY–IN | 1992 | 49 | 12 | 194 | 109 | 27 | 430 |

| 1993 | 43 | 11 | 171 | 84 | 22 | 335 | |

| 1994 | 60 | 15 | 237 | 107 | 27 | 423 | |

| 1995 | 53 | 13 | 210 | 85 | 21 | 338 | |

| 1996 | 58 | 15 | 228 | 83 | 21 | 326 | |

| 1997 | 62 | 16 | 244 | 79 | 20 | 309 | |

| 1998 | 66 | 16 | 257 | 73 | 18 | 285 | |

| 1999 | 78 | 20 | 306 | 76 | 19 | 296 | |

| 2000 | 71 | 18 | 279 | 61 | 15 | 239 | |

| 2001 | 88 | 22 | 344 | 70 | 17 | 273 | |

| 2002 | 79 | 20 | 309 | 59 | 15 | 231 | |

| Memphis, TN–AR–MS | 1992 | 38 | 12 | 125 | 55 | 17 | 181 |

| 1993 | 39 | 12 | 127 | 50 | 16 | 164 | |

| 1994 | 39 | 12 | 127 | 44 | 14 | 144 | |

| 1995 | 37 | 11 | 122 | 36 | 11 | 120 | |

| 1996 | 37 | 11 | 120 | 31 | 9 | 102 | |

| 1997 | 37 | 11 | 122 | 28 | 8 | 91 | |

| 1998 | 39 | 12 | 129 | 25 | 8 | 83 | |

| 1999 | 50 | 15 | 163 | 28 | 9 | 93 | |

| 2000 | 47 | 14 | 152 | 24 | 7 | 76 | |

| 2001 | 58 | 17 | 189 | 28 | 8 | 90 | |

| 2002 | 55 | 16 | 178 | 25 | 7 | 81 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Miami, FL | 1992 | 5,238 | 2,309 | 10,089 | 75 | 33 | 145 |

| 1993 | 3,823 | 1,689 | 7,338 | 54 | 24 | 104 | |

| 1994 | 4,429 | 1,962 | 8,468 | 61 | 27 | 117 | |

| 1995 | 3,337 | 1,482 | 6,354 | 44 | 20 | 84 | |

| 1996 | 3,160 | 1,408 | 5,988 | 40 | 18 | 76 | |

| 1997 | 2,943 | 1,315 | 5,548 | 36 | 16 | 69 | |

| 1998 | 2,906 | 1,304 | 5,447 | 35 | 16 | 66 | |

| 1999 | 3,396 | 1,530 | 6,326 | 40 | 18 | 74 | |

| 2000 | 2,831 | 1,282 | 5,239 | 32 | 14 | 59 | |

| 2001 | 3,265 | 1,485 | 6,000 | 36 | 16 | 66 | |

| 2002 | 2,817 | 1,287 | 5,139 | 31 | 14 | 56 | |

| Middlesex–Somerset–Hunterdon, NJ | 1992 | 843 | 342 | 1,894 | 145 | 59 | 325 |

| 1993 | 837 | 340 | 1,875 | 135 | 55 | 302 | |

| 1994 | 799 | 325 | 1,784 | 121 | 49 | 271 | |

| 1995 | 795 | 324 | 1,769 | 114 | 46 | 253 | |

| 1996 | 782 | 319 | 1,734 | 105 | 43 | 233 | |

| 1997 | 772 | 316 | 1,705 | 97 | 40 | 215 | |

| 1998 | 785 | 322 | 1,726 | 94 | 38 | 206 | |

| 1999 | 800 | 329 | 1,749 | 91 | 37 | 198 | |

| 2000 | 829 | 342 | 1,804 | 89 | 37 | 194 | |

| 2001 | 847 | 351 | 1,832 | 87 | 36 | 187 | |

| 2002 | 880 | 365 | 1,892 | 86 | 36 | 185 | |

| Milwaukee–Waukesha, WI | 1992 | 608 | 233 | 1,428 | 172 | 66 | 403 |

| 1993 | 526 | 202 | 1,234 | 139 | 53 | 326 | |

| 1994 | 641 | 246 | 1,500 | 157 | 60 | 368 | |

| 1995 | 569 | 218 | 1,328 | 129 | 50 | 302 | |

| 1996 | 593 | 228 | 1,381 | 126 | 48 | 294 | |

| 1997 | 616 | 237 | 1,430 | 123 | 47 | 285 | |

| 1998 | 653 | 252 | 1,510 | 122 | 47 | 282 | |

| 1999 | 728 | 282 | 1,678 | 128 | 50 | 295 | |

| 2000 | 690 | 267 | 1,582 | 114 | 44 | 262 | |

| 2001 | 788 | 306 | 1,800 | 124 | 48 | 284 | |

| 2002 | 735 | 286 | 1,670 | 110 | 43 | 251 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Minneapolis–St. Paul, MN–WI | 1992 | 276 | 100 | 739 | 97 | 35 | 260 |

| 1993 | 230 | 84 | 615 | 73 | 27 | 195 | |

| 1994 | 274 | 99 | 732 | 80 | 29 | 213 | |

| 1995 | 230 | 84 | 615 | 60 | 22 | 161 | |

| 1996 | 233 | 85 | 622 | 54 | 20 | 145 | |

| 1997 | 248 | 90 | 660 | 51 | 19 | 137 | |

| 1998 | 263 | 95 | 699 | 49 | 18 | 129 | |

| 1999 | 336 | 122 | 893 | 56 | 20 | 148 | |

| 2000 | 300 | 109 | 794 | 45 | 17 | 120 | |

| 2001 | 396 | 144 | 1,049 | 56 | 20 | 149 | |

| 2002 | 349 | 127 | 922 | 47 | 17 | 124 | |

| Monmouth–Ocean, NJ | 1992 | 376 | 143 | 979 | 137 | 52 | 357 |

| 1993 | 324 | 123 | 843 | 111 | 42 | 289 | |

| 1994 | 347 | 132 | 900 | 112 | 43 | 292 | |

| 1995 | 320 | 122 | 830 | 97 | 37 | 253 | |

| 1996 | 319 | 121 | 825 | 91 | 35 | 236 | |

| 1997 | 323 | 123 | 833 | 87 | 33 | 224 | |

| 1998 | 339 | 130 | 873 | 86 | 33 | 222 | |

| 1999 | 322 | 123 | 827 | 78 | 30 | 200 | |

| 2000 | 372 | 142 | 952 | 85 | 32 | 218 | |

| 2001 | 327 | 125 | 835 | 70 | 27 | 180 | |

| 2002 | 414 | 159 | 1,052 | 84 | 32 | 213 | |

| Nashville, TN | 1992 | 61 | 20 | 185 | 86 | 28 | 262 |

| 1993 | 59 | 19 | 178 | 71 | 23 | 215 | |

| 1994 | 77 | 25 | 233 | 77 | 25 | 233 | |

| 1995 | 72 | 24 | 218 | 59 | 20 | 179 | |

| 1996 | 80 | 26 | 241 | 54 | 18 | 163 | |

| 1997 | 86 | 28 | 260 | 49 | 16 | 147 | |

| 1998 | 91 | 30 | 274 | 43 | 14 | 128 | |

| 1999 | 109 | 36 | 328 | 43 | 14 | 130 | |

| 2000 | 97 | 32 | 292 | 33 | 11 | 99 | |

| 2001 | 115 | 37 | 345 | 36 | 11 | 107 | |

| 2002 | 105 | 34 | 315 | 31 | 10 | 92 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Nassau–Suffolk, NY | 1992 | 909 | 355 | 2,225 | 69 | 27 | 168 |

| 1993 | 903 | 353 | 2,206 | 64 | 25 | 157 | |

| 1994 | 897 | 351 | 2,186 | 61 | 24 | 148 | |

| 1995 | 960 | 376 | 2,334 | 62 | 24 | 151 | |

| 1996 | 993 | 390 | 2,410 | 61 | 24 | 148 | |

| 1997 | 1,050 | 413 | 2,539 | 61 | 24 | 149 | |

| 1998 | 1,115 | 439 | 2,688 | 62 | 24 | 150 | |

| 1999 | 929 | 367 | 2,230 | 49 | 19 | 118 | |

| 2000 | 1,222 | 483 | 2,920 | 62 | 24 | 148 | |

| 2001 | 955 | 379 | 2,273 | 46 | 18 | 110 | |

| 2002 | 1,336 | 530 | 3,166 | 62 | 24 | 146 | |

| New Haven–Meriden, CT | 1992 | 4,887 | 2,208 | 9,054 | 551 | 249 | 1,021 |

| 1993 | 4,567 | 2,069 | 8,430 | 493 | 223 | 910 | |

| 1994 | 4,768 | 2,166 | 8,767 | 494 | 224 | 908 | |

| 1995 | 4,668 | 2,126 | 8,545 | 463 | 211 | 848 | |

| 1996 | 4,722 | 2,157 | 8,602 | 445 | 203 | 810 | |

| 1997 | 4,790 | 2,197 | 8,681 | 430 | 197 | 779 | |

| 1998 | 4,788 | 2,206 | 8,627 | 413 | 190 | 744 | |

| 1999 | 4,614 | 2,135 | 8,260 | 381 | 176 | 683 | |

| 2000 | 4,698 | 2,185 | 8,355 | 371 | 173 | 661 | |

| 2001 | 4,541 | 2,123 | 8,017 | 345 | 161 | 609 | |

| 2002 | 4,604 | 2,163 | 8,071 | 335 | 157 | 588 | |

| New Orleans, LA | 1992 | 240 | 85 | 666 | 63 | 22 | 176 |

| 1993 | 198 | 70 | 549 | 52 | 18 | 145 | |

| 1994 | 252 | 89 | 698 | 66 | 23 | 182 | |

| 1995 | 209 | 74 | 579 | 54 | 19 | 148 | |

| 1996 | 214 | 76 | 592 | 55 | 19 | 151 | |

| 1997 | 221 | 78 | 610 | 56 | 20 | 154 | |

| 1998 | 228 | 81 | 630 | 57 | 20 | 158 | |

| 1999 | 289 | 103 | 798 | 72 | 26 | 199 | |

| 2000 | 242 | 86 | 668 | 60 | 21 | 165 | |

| 2001 | 307 | 109 | 845 | 74 | 26 | 203 | |

| 2002 | 259 | 92 | 713 | 60 | 21 | 166 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| New York, NY | 1992 | 40,762 | 19,585 | 69,210 | 304 | 146 | 517 |

| 1993 | 41,256 | 19,882 | 69,788 | 300 | 145 | 508 | |

| 1994 | 38,852 | 18,782 | 65,458 | 276 | 134 | 466 | |

| 1995 | 39,547 | 19,183 | 66,334 | 276 | 134 | 462 | |

| 1996 | 38,804 | 18,895 | 64,770 | 265 | 129 | 442 | |

| 1997 | 38,131 | 18,649 | 63,304 | 254 | 124 | 422 | |

| 1998 | 38,016 | 18,685 | 62,743 | 247 | 122 | 408 | |

| 1999 | 35,515 | 17,550 | 58,243 | 227 | 112 | 372 | |

| 2000 | 38,162 | 18,968 | 62,161 | 239 | 119 | 389 | |

| 2001 | 34,699 | 17,349 | 56,122 | 214 | 107 | 346 | |

| 2002 | 38,136 | 19,179 | 61,237 | 233 | 117 | 374 | |

| Newark, NJ | 1992 | 4,137 | 1,722 | 8,853 | 288 | 120 | 617 |

| 1993 | 3,583 | 1,494 | 7,643 | 240 | 100 | 511 | |

| 1994 | 3,850 | 1,608 | 8,186 | 249 | 104 | 529 | |

| 1995 | 3,406 | 1,425 | 7,216 | 212 | 89 | 450 | |

| 1996 | 3,353 | 1,406 | 7,075 | 201 | 84 | 424 | |

| 1997 | 3,309 | 1,391 | 6,949 | 191 | 80 | 400 | |

| 1998 | 3,318 | 1,399 | 6,932 | 184 | 78 | 384 | |

| 1999 | 3,351 | 1,418 | 6,962 | 180 | 76 | 374 | |

| 2000 | 3,359 | 1,427 | 6,937 | 175 | 74 | 361 | |

| 2001 | 3,231 | 1,378 | 6,632 | 162 | 69 | 332 | |

| 2002 | 3,452 | 1,477 | 7,041 | 167 | 71 | 340 | |

| Norfolk–Virginia Beach–Newport News, VA–NC | 1992 | 116 | 41 | 324 | 49 | 17 | 137 |

| 1993 | 116 | 41 | 324 | 47 | 17 | 132 | |

| 1994 | 138 | 48 | 385 | 55 | 19 | 154 | |

| 1995 | 130 | 46 | 363 | 50 | 18 | 139 | |

| 1996 | 138 | 48 | 385 | 50 | 17 | 140 | |

| 1997 | 146 | 51 | 408 | 51 | 18 | 142 | |

| 1998 | 151 | 53 | 420 | 51 | 18 | 141 | |

| 1999 | 183 | 64 | 509 | 59 | 20 | 163 | |

| 2000 | 165 | 58 | 459 | 50 | 17 | 138 | |

| 2001 | 195 | 69 | 543 | 56 | 20 | 157 | |

| 2002 | 179 | 63 | 498 | 49 | 17 | 136 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Oakland, CA | 1992 | 3,542 | 1,444 | 7,904 | 173 | 71 | 387 |

| 1993 | 4,088 | 1,669 | 9,094 | 192 | 78 | 427 | |

| 1994 | 3,468 | 1,418 | 7,693 | 157 | 64 | 348 | |

| 1995 | 3,995 | 1,637 | 8,833 | 174 | 71 | 385 | |

| 1996 | 4,004 | 1,643 | 8,819 | 167 | 69 | 368 | |

| 1997 | 4,099 | 1,686 | 8,990 | 162 | 67 | 356 | |

| 1998 | 4,160 | 1,716 | 9,081 | 156 | 64 | 341 | |

| 1999 | 3,931 | 1,627 | 8,538 | 141 | 58 | 305 | |

| 2000 | 4,152 | 1,724 | 8,968 | 142 | 59 | 306 | |

| 2001 | 4,042 | 1,683 | 8,680 | 132 | 55 | 283 | |

| 2002 | 4,006 | 1,673 | 8,553 | 127 | 53 | 271 | |

| Oklahoma City, OK | 1992 | 131 | 47 | 358 | 53 | 19 | 145 |

| 1993 | 144 | 52 | 394 | 54 | 19 | 148 | |

| 1994 | 127 | 46 | 348 | 44 | 16 | 121 | |

| 1995 | 134 | 48 | 365 | 43 | 15 | 117 | |

| 1996 | 128 | 46 | 350 | 38 | 14 | 103 | |

| 1997 | 126 | 45 | 343 | 34 | 12 | 93 | |

| 1998 | 127 | 46 | 346 | 31 | 11 | 86 | |

| 1999 | 131 | 47 | 356 | 29 | 11 | 80 | |

| 2000 | 136 | 49 | 369 | 29 | 10 | 78 | |

| 2001 | 143 | 51 | 388 | 28 | 10 | 77 | |

| 2002 | 147 | 53 | 398 | 27 | 10 | 74 | |

| Omaha, NE–IA | 1992 | 82 | 29 | 221 | 65 | 23 | 175 |

| 1993 | 88 | 32 | 237 | 63 | 23 | 171 | |

| 1994 | 88 | 31 | 235 | 57 | 20 | 153 | |

| 1995 | 91 | 32 | 243 | 53 | 19 | 142 | |

| 1996 | 93 | 33 | 248 | 49 | 17 | 131 | |

| 1997 | 92 | 33 | 247 | 45 | 16 | 120 | |

| 1998 | 97 | 35 | 260 | 43 | 16 | 116 | |

| 1999 | 113 | 41 | 302 | 47 | 17 | 124 | |

| 2000 | 116 | 42 | 308 | 45 | 16 | 118 | |

| 2001 | 134 | 48 | 356 | 48 | 17 | 128 | |

| 2002 | 137 | 49 | 364 | 47 | 17 | 124 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Orange County, CA | 1992 | 8,395 | 4,004 | 14,394 | 202 | 96 | 347 |

| 1993 | 9,012 | 4,311 | 15,395 | 209 | 100 | 357 | |

| 1994 | 7,641 | 3,666 | 13,000 | 171 | 82 | 290 | |

| 1995 | 8,176 | 3,936 | 13,848 | 176 | 85 | 299 | |

| 1996 | 7,962 | 3,848 | 13,421 | 166 | 80 | 279 | |

| 1997 | 8,012 | 3,889 | 13,432 | 159 | 77 | 266 | |

| 1998 | 8,130 | 3,965 | 13,549 | 153 | 75 | 256 | |

| 1999 | 7,357 | 3,607 | 12,183 | 134 | 66 | 222 | |

| 2000 | 7,969 | 3,930 | 13,108 | 140 | 69 | 230 | |

| 2001 | 6,797 | 3,371 | 11,100 | 116 | 58 | 189 | |

| 2002 | 7,726 | 3,854 | 12,527 | 129 | 64 | 209 | |

| Orlando, FL | 1992 | 1,631 | 708 | 3,225 | 191 | 83 | 379 |

| 1993 | 1,515 | 659 | 2,986 | 161 | 70 | 317 | |

| 1994 | 1,865 | 813 | 3,661 | 180 | 79 | 354 | |

| 1995 | 1,704 | 744 | 3,331 | 149 | 65 | 292 | |

| 1996 | 1,828 | 801 | 3,558 | 144 | 63 | 281 | |

| 1997 | 1,978 | 870 | 3,831 | 141 | 62 | 273 | |

| 1998 | 2,136 | 942 | 4,113 | 139 | 61 | 267 | |

| 1999 | 2,747 | 1,217 | 5,257 | 162 | 72 | 310 | |

| 2000 | 2,565 | 1,141 | 4,877 | 137 | 61 | 261 | |

| 2001 | 3,220 | 1,439 | 6,081 | 159 | 71 | 301 | |

| 2002 | 3,058 | 1,373 | 5,735 | 141 | 63 | 264 | |

| Philadelphia, PA–NJ | 1992 | 5,583 | 2,220 | 13,153 | 453 | 180 | 1,066 |

| 1993 | 5,432 | 2,162 | 12,766 | 423 | 168 | 995 | |

| 1994 | 6,094 | 2,429 | 14,284 | 457 | 182 | 1,070 | |

| 1995 | 5,818 | 2,322 | 13,600 | 419 | 167 | 979 | |

| 1996 | 5,973 | 2,387 | 13,916 | 411 | 164 | 958 | |

| 1997 | 6,098 | 2,442 | 14,157 | 403 | 161 | 935 | |

| 1998 | 6,332 | 2,542 | 14,641 | 402 | 161 | 929 | |

| 1999 | 7,353 | 2,958 | 16,924 | 451 | 181 | 1,038 | |

| 2000 | 7,046 | 2,843 | 16,141 | 417 | 168 | 954 | |

| 2001 | 8,447 | 3,417 | 19,253 | 482 | 195 | 1,098 | |

| 2002 | 8,091 | 3,280 | 18,352 | 444 | 180 | 1,008 | |

| Metropolitan area | Year | Number | 95 % confidence interval | Rate | 95 % confidence interval | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Phoenix–Mesa, AZ | 1992 | 3,387 | 1,415 | 7,153 | 122 | 51 | 257 |

| 1993 | 3,398 | 1,423 | 7,155 | 112 | 47 | 236 | |

| 1994 | 3,640 | 1,527 | 7,638 | 109 | 46 | 230 | |

| 1995 | 3,668 | 1,542 | 7,667 | 101 | 42 | 211 | |

| 1996 | 3,769 | 1,588 | 7,846 | 95 | 40 | 199 | |

| 1997 | 3,928 | 1,660 | 8,139 | 92 | 39 | 190 | |

| 1998 | 4,266 | 1,808 | 8,793 | 93 | 39 | 191 | |

| 1999 | 5,023 | 2,136 | 10,295 | 102 | 43 | 209 | |

| 2000 | 5,100 | 2,177 | 10,390 | 97 | 41 | 197 | |

| 2001 | 6,270 | 2,687 | 12,693 | 112 | 48 | 226 | |

| 2002 | 6,256 | 2,690 | 12,583 | 105 | 45 | 211 | |

| Pittsburgh, PA | 1992 | 101 | 35 | 288 | 110 | 38 | 313 |

| 1993 | 94 | 32 | 268 | 100 | 34 | 285 | |

| 1994 | 110 | 38 | 315 | 114 | 40 | 328 | |

| 1995 | 102 | 35 | 291 | 104 | 36 | 297 | |

| 1996 | 106 | 37 | 304 | 105 | 37 | 300 | |

| 1997 | 110 | 38 | 313 | 106 | 37 | 303 | |

| 1998 | 116 | 40 | 332 | 110 | 38 | 314 | |

| 1999 | 138 | 48 | 395 | 128 | 44 | 365 | |

| 2000 | 133 | 46 | 378 | 117 | 40 | 331 | |

| 2001 | 153 | 53 | 435 | 126 | 44 | 357 | |

| 2002 | 154 | 54 | 440 | 119 | 42 | 340 | |

| Portland–Vancouver, OR–WA | 1992 | 784 | 295 | 2,100 | 189 | 71 | 506 |

| 1993 | 875 | 330 | 2,342 | 188 | 71 | 504 | |

| 1994 | 786 | 297 | 2,101 | 152 | 57 | 405 | |

| 1995 | 913 | 345 | 2,438 | 157 | 59 | 418 | |

| 1996 | 942 | 356 | 2,511 | 146 | 55 | 388 | |

| 1997 | 978 | 370 | 2,602 | 135 | 51 | 360 | |

| 1998 | 1,026 | 388 | 2,726 | 129 | 49 | 343 | |

| 1999 | 929 | 352 | 2,461 | 106 | 40 | 281 | |