Abstract

Spinal cord development is a complex process involving generation of the appropriate number of cells, acquisition of distinctive phenotypes and establishment of functional connections that enable execution of critical functions such as sensation and locomotion. Here we review the basic cellular events occurring during spinal cord development, highlighting studies that demonstrate the roles of electrical activity in this process. We conclude that the participation of different forms of electrical activity is evident from the beginning of spinal cord development and intermingles with other developmental cues and programs to implement dynamic and integrated control of spinal cord function.

Introduction

Spinal cord circuits underlie a complex array of amazing functions. Specialized connections among its cells and with target tissues allow for tasks ranging from sensation through locomotion. The prevailing view is that the formation of such powerful circuits is achieved through a hardwired genetic program that is turned on at the earliest embryological stages of spinal cord development [1]. However, more recently, several lines of evidence have argued in favor of a more dynamic plan for spinal cord development, in which changes in intrinsic and extrinsic cues have an impact on the course of progressive differentiation of neurons and maturation of newly formed connections. Although the panoply of factors that influence spinal cord development is vast, electrical activity and Ca2+-mediated signaling (see Box 1) are common features in the transduction of these developmental cues.

Here we review recent work on the development of spinal circuits from the moment neurons are generated, differentiate, extend their axons and establish connections, emphasizing how each of these stages is the result of both an early patterning program and electrical activity.

Generation of spinal cells: achieving the appropriate number

Spinal cord neurons are born shortly after the ectoderm is induced to become neural tissue. They appear earlier than neurons in the brain, suggesting the more immediate need of their function in the developing embryo. Among them, primary motor and sensory neurons are the first to be generated, while interneurons are born later. The rate of generation of these cells is set by the progression of neural progenitors through the cell cycle. A combination of different morphogenetic protein gradients along the dorsoventral axis of the developing spinal cord contributes to the timing of cell cycle exit and the specification of domains of identity of spinal progenitors, depending on their relative location with respect to these secreted protein gradients [1-3].

Interestingly, exiting the cell cycle and the transition to specialized neuronal phenotypes is also dependent on neurotransmitter signaling. Knockdown of the embryonic α2 glycine receptor subunit alters the proliferation rate of spinal neuron progenitors and thus decreases the number of spinal interneurons [4]. Moreover, imposing a mature chloride gradient during zebrafish development by overexpression of the potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2, which prevents the early depolarizing action of neurotransmitters GABA and glycine, leads to a reduction in the number of interneurons and motor neurons. This is due to impairment of the transition of progenitors to these distinctive neuronal phenotypes [5].

Even after spinal neurons are generated, the numbers of different cell subtypes are revised at later developmental stages. The interaction with target tissues and the neurotrophic factors they secrete determine the number of motor neurons that will survive and innervate the muscle. Indeed, approximately 50% of spinal motor neurons initially generated die in the developing chicken, rat and mouse spinal cord. This programmed cell death is regulated by electrical activity [6,7] and trophic factor secretion from target skeletal muscle [8,9]. This event is not exclusive to the motor neurons in the spinal cord, because genetic or pharmacological blockade of Na+ channel-mediated electrical activity enhances survival of primary sensory Rohon-Beard neurons, a transitory population in developing zebrafish [10].

Spinal cell differentiation: Cell fate revisited

Spinal cord neurons acquire their distinctive identity early in development. Specialization of these phenotypes starts with the dorsoventral patterning of neural progenitors, which leads to the combinatorial expression of transcription factors that directs the identity of spinal neurons. Although many studies have identified the existence of a transcription factor code that determines spinal neuron phenotypes from the time that the progenitor cells are specified, many other studies have demonstrated that this genetic program of differentiation is not as rigid and predetermined as initially thought. Instead, changes in electrical activity and environmental cues have a profound impact on the identity of developing spinal neurons. Prolonged slowing or blockade of spontaneous electrical activity in the embryonic chick spinal cord downregulates expression of the transcription factors Lim1 and Islet1 in developing motor neurons [11]. Phosphorylation of the transcription factor Olig2 by a yet unknown kinase controls the cell fate switch between the motor neuron and oligodendroglial phenotypes in the developing mouse spinal cord [12•]. These results predict that either electrical activity or other intrinsic or extrinsic cues that modify the activity status of the relevant kinase may have an impact on the differentiation of Olig2 progenitor cells. Aside from dorsoventral patterning, other parameters such as the timing of neurogenesis and proprioceptive sensory feedback from the periphery greatly contribute to cell specialization, as shown in a recent report for the functional segregation of extensor-flexor premotor interneurons [13••]. Taken together, these studies suggest that spinal neuron specification is dynamic and integrates multiple developmental cues.

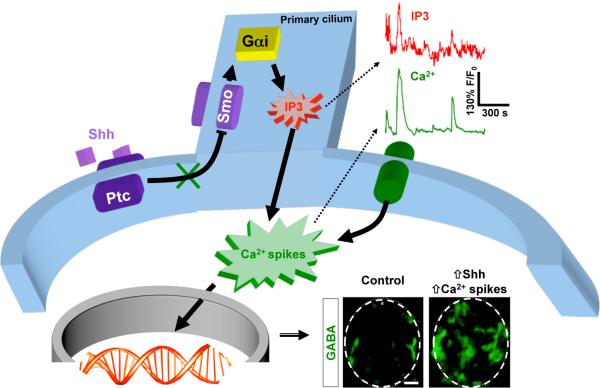

The process of cell differentiation has the ultimate objective of providing the cell with the appropriate molecular machinery to promote the function of the nervous system. One of the most important aspects of neuronal differentiation is the specification of neurotransmitter phenotype, because this enables the neuron to establish synaptic connections with its target cells. Neurotransmitter specification in spinal cord neurons follows an activity-dependent homeostatic paradigm, such that when electrical activity is suppressed more spinal neurons express excitatory neurotransmitters, and when activity is enhanced more neurons express inhibitory neurotransmitters [14]. The switch between glutamatergic and GABAergic phenotypes is governed by the activity-dependent regulation of the transcription factor Tlx3 through the recruitment of phospho-cJun [15••]. This indicates that although a genetic program was triggered early on, leading to the expression of Tlx3 and the specification of glutamatergic spinal neurons, changes in electrical activity modify the status of this transcription factor and thereby induce transmitter respecification. These results demonstrate that electrical activity is a key component of the differentiation program. Indeed, our recent work has shown that there is interplay between morphogenetic proteins that are drivers of early patterning of the spinal cord, and electrical activity in developing spinal neurons. Sonic hedgehog (Shh) acutely regulates the level of Ca2+-mediated electrical activity in Xenopus embryonic spinal neurons. We found that activation of Smoothened, a Shh coreceptor, increases Ca2+ spike activity in spinal neurons through a novel signaling mechanism mediated by recruitment of the heterotrimeric G-protein-αi, phospholipase C and transient receptor potential channel 1 (TRPC1). This machinery leads to correlated Ca2+ and IP3 transients, with the latter localized at the neuronal primary cilium. Shh-induced enhancement of Ca2+ spike activity increases the number of GABAergic spinal neurons without affecting total number of cells or specification of neural progenitors [16••] (Figure 1). Other environmental cues have been shown to regulate spinal cell differentiation. Binding of the hepatocyte growth factor to its receptor, Met, is necessary for normal development of zebrafish primary and secondary motor neurons. The latter do not form in the absence of Met and the primary motor neurons develop a hybrid phenotype in which they co-express motor neuron and interneuron neurotransmitters and have both peripheral and central axons [17]. Moreover, despite the initial patterning of spinal neuron progenitors and the apparent fate assignment occurring early in development, Netrin 1a from muscle acts as an intermediate target-derived signal that causes two equivalent motor neurons to adopt distinct fates. This suggests a role for intermediate targets in breaking neuronal equivalence. Such signals may be key to diversifying a neuronal population and leading to correct circuit formation [18•].

Figure 1. Interplay between Sonic hedgehog and Ca2+ spike activity for the regulation of neurotransmitter specification in embryonic spinal neurons.

Activation of Smoothened (Smo) by Sonic hedgehog (Shh) recruits the heterotrimeric G protein (Gαi) leading to transients of inositol triphosphate (IP3) at the primary cilium, which contribute to increase the level of Ca2+ spike activity in embryonic spinal neurons. This Shh-induced enhancement in Ca2+ spikes increases the number of spinal neurons expressing the GABAergic phenotype. Ptc1, Patched1. Outlined with dashed line, transverse section of spinal cord, scale bar: 20 μm.

Neurite morphology is another crucial feature that neurons acquire during the process of differentiation. Perturbation of nitric oxide signaling during development of the zebrafish spinal cord alters morphogenesis of motor axons, demonstrating that signaling from developing interneurons influences differentiation of motor neurons [19•]. The role of electrical activity and neurotransmitter signaling in shaping spinal neuron morphology is also apparent in mammals; neurite outgrowth in developing rat motor neurons is dependent on glutamate-mediated electrical activity during a critical period [20-23]. GluR1 promotes dendrite growth in a non-cell-autonomous manner in vitro in the developing rat spinal cord and in vivo in mice [24]. The early adoption of dendritic over axonal identity in spinal commissural interneurons is dependent on Semaphorin 3A-mediated Ca2+ signaling through the local upregulation and activation of Cav2.3 channels [25].

Axon guidance in developing spinal neurons

Concomitant with neuronal differentiation, spinal neurons extend their axons and navigate the developing nervous system in search of the appropriate target. This aspect of the development of spinal circuits is governed by intrinsic, extrinsic, activity-dependent and independent cues. Spontaneous electrical activity in the developing chick spinal cord is important for motor neuron axonal pathfinding. Decreasing this Ca2+-mediated rhythmic bursting activity induces errors in the dorsoventral routing of motor neuron axons. These abnormalities are correlated with changes in expression of cell adhesion molecules that interact with guidance cues and regulate motor neuron fasciculation and innervation of appropriate muscles [11]. Increasing the frequency of the rhythmic bursting activity in the embryonic spinal cord does not affect the dorsoventral pathfinding of motor neuron axons but instead perturbs the anteroposterior routing of these axons [26]. Interestingly these errors can be rectified at a later stage, when axons are further along their trajectory, by restoring appropriate levels of electrical activity; these results suggest that control of the process of axonal pathfinding by electrical activity is dynamic [26]. More recently, Landmesser and colleagues elegantly demonstrated that restoring patterns of spontaneous activity by means of light-activated channelrhodopsin-2 on the background of pharmacological blockade of GABAA receptor signaling rescues pathfinding errors of developing motor axons [27••]. Expression of the appropriate transcription factors accompanies the subspecification of motor neuron pools and targeting of distinct muscle types [28] and changes in spontaneous activity in the spinal cord also alter expression of some of these transcription factors [11,27••].

Regulation of motor neuron axonal trajectories by early electrical activity is not exclusive to the chick and has also been identified in secondary motor neurons of the larval zebrafish. Knockdown of Nav1.6a channels leads to morphological defects in axons of motor neurons expressing this channel and also acts non-cell autonomously in subtypes of motor neurons that do not express this channel [29]. This non-cell autonomous Nav1.6-mediated regulation of motor neuron axon pathfinding may depend on release of guidance cues and/or trophic factors from either target tissues or neighboring cells or electrical coupling present in the developing spinal cord and motor neuron pools [29-31].

Synapse formation and plasticity

Once cells differentiate and extend their axons the next step towards establishing spinal circuitry consists of formation of synapses. Synaptogenesis and maturation of newly formed synapses are processes strongly governed by interactions with target tissues, neighboring cells and by electrical activity and neurotransmitter signaling. Spontaneous activity in the emerging circuitry produces simple motor behaviors and reinforces functional synaptic connectivity within central pattern generators. Alterations in this spontaneous activity exert profound effects on circuit formation. For instance, NMDA receptor blockade maintains correlated motor neuron firing and delays synapse competition at developing neuromuscular junctions [32].

In addition to the role of spontaneous electrical activity in synapse formation and elimination, this activity also regulates synaptic strength during spinal cord development. In particular, it has been shown that reducing spontaneous network activity in the developing chick spinal cord results in compensatory increases in synaptic strength of both AMPAergic and depolarizing GABAergic currents [33]. Moreover, these homeostatic changes in synaptic strength are accompanied by homeostatic changes in cellular excitability through an increase in sodium currents and the reduction of fast-inactivating and calcium-activated potassium currents [34••]. The intrinsic excitability of developing spinal neurons and the timing with which they are incorporated into the developing spinal circuitry is crucial to the progression of different motor behaviors in the developing larval zebrafish. In recent years Fetcho and colleagues have developed a comprehensive map of temporal and topographic assembly of motor circuits during zebrafish spinal cord development (reviewed in [35]). They elegantly demonstrated that spinal neurons involved in faster movements are generated and differentiate first while the ones recruited in slower movements differentiate later, in agreement with natural sequence of occurrence of motor behaviors [36]. This appears to be due to the fact that excitatory dorsal spinal neurons require higher levels of stimulation to be recruited than their ventral counterparts, while inhibitory spinal neurons show the opposite pattern, and this topography underlies distinctive swimming behaviors [37]. This profile seems to be rooted in early development through an orderly addition of neurons to the developing network [36]. It may occur in other vertebrates as well, because a dorsoventral gradient of excitability is also present in Xenopus [14,16,38] and in chick [39] embryonic spinal cords. It will be interesting to challenge the developing embryo to different environments that may require either different types of motor behaviors or different rates of occurrence and test whether the assembly of circuits changes accordingly. Naturally occurring changes in environmental stimuli during spinal cord development can be difficult to determine, like a change in diet or a stressful situation or they can be readily identified, as for tissue injury. Using an incision through the skin and muscle as a model of surgical injury, Baccei and colleagues demonstrated that synapses within the spinal superficial dorsal horn (SDH) respond to injury in an activity-dependent manner: surgical injury during early life first potentiates, but later depresses, glutamatergic signaling in the SDH [40•].

Conclusions

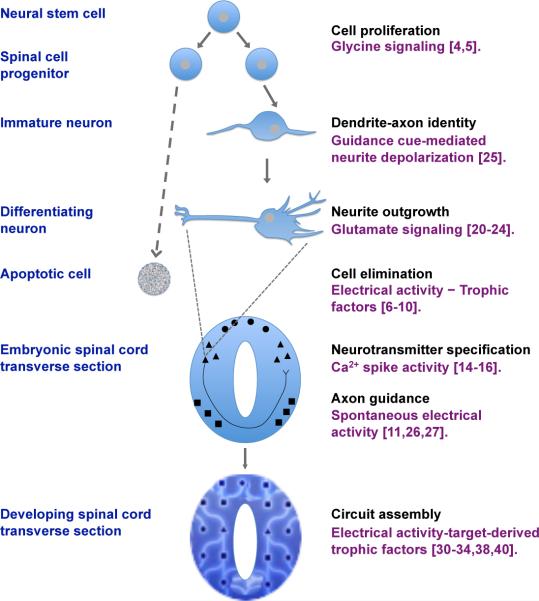

Spinal cord development and establishment of functional circuits take place through the combined contribution of both hardwired genetic programs and electrical activity. Understanding the basis of this shared effort is not trivial. The role of electrical activity as a developmental cue starts earlier than previously appreciated and enables activity-dependent regulation of the number of neurons and their differentiation before mature synapses and circuits are established (Figure 2). Although revising neuronal numbers or respecifying neurotransmitter identity after the genetic program has dictated their “fate” may seem counterintuitive and inefficient, electrical activity may allow adaptability of the developing system according to the environment that surrounds it. Future efforts should be directed towards assessing how natural changes in the environment affect the developing spinal cord and its ability to compensate for perturbations to its surroundings.

Figure 2. The integration of diverse intrinsic and extrinsic cues during spinal cord development is facilitated by early electrical activity.

Different forms of electrical activity regulate important events of spinal cord development starting at the early stages of neuronal generation and extending to later stages of circuit formation and synaptic plasticity.

Highlights.

Electrical activity manifests during early stages of spinal cord development.

Cell number, differentiation and axon guidance are regulated by electrical activity

Establishment of synapses and changes in synaptic strength are activity-dependent

Box 1. Spontaneous electrical activity during nervous system development.

The presence of electrical activity before or during synapse formation is evident in species ranging from invertebrates such as Manduca [41] and Drosophila [42] to vertebrates such as the turtle [43], frog [14,16,44••,45], chick [46,47], ferret [48,49] and mouse [50,51]. It is observed in many different nervous system structures, arguing for a universal character of this activity. It varies with respect to the mechanisms underlying it and the roles that it plays. In general it is Ca2+-mediated and manifested transiently during a critical period that terminates after circuits are functionally established. In the developing retina, Ca2+ waves are critical to instruct the formation of eye-specific retinogeniculate projections [52-54]. In the mouse embryonic cortex, events as early as neuronal migration and elaboration of dendrites and axons of pyramidal cells [55,56] and GABAergic interneurons [57••] are dependent on early electrical activity.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nick Spitzer for comments on the manuscript. Work in the Borodinsky lab has been supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS073055, LN Borodinsky), National Science Foundation (Grant #1120796, LN Borodinsky), Joseph A & Esther Klingenstein Fund (Neuroscience Award 2008, LN Borodinsky), March of Dimes (Basil O'Connor Award 2009, LN Borodinsky), Shriners Hospital for Children (Research Grant #08-NCA-013, LN Borodinsky and Postdoctoral Fellowships 2008, YH Belgacem and I Swapna).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tanabe Y, Jessell TM. Diversity and pattern in the developing spinal cord. Science. 1996;274:1115–1123. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez FJ, Jonas PC, Sapir T, Hartley R, Berrocal MC, Geiman EJ, Todd AJ, Goulding M. Postnatal phenotype and localization of spinal cord V1 derived interneurons. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:177–192. doi: 10.1002/cne.20711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song MR, Sun Y, Bryson A, Gill GN, Evans SM, Pfaff SL. Islet-to-LMO stoichiometries control the function of transcription complexes that specify motor neuron and V2a interneuron identity. Development. 2009;136:2923–2932. doi: 10.1242/dev.037986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDearmid JR, Liao M, Drapeau P. Glycine receptors regulate interneuron differentiation during spinal network development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9679–9684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504871103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynolds A, Brustein E, Liao M, Mercado A, Babilonia E, Mount DB, Drapeau P. Neurogenic role of the depolarizing chloride gradient revealed by global overexpression of KCC2 from the onset of development. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1588–1597. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3791-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banks GB, Kanjhan R, Wiese S, Kneussel M, Wong LM, O'Sullivan G, Sendtner M, Bellingham MC, Betz H, Noakes PG. Glycinergic and GABAergic synaptic activity differentially regulate motoneuron survival and skeletal muscle innervation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1249–1259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1786-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oppenheim RW, Caldero J, Cuitat D, Esquerda J, Ayala V, Prevette D, Wang S. Rescue of developing spinal motoneurons from programmed cell death by the GABA(A) agonist muscimol acts by blockade of neuromuscular activity and increased intramuscular nerve branching. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:331–343. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(02)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oppenheim RW, Prevette D, Yin QW, Collins F, MacDonald J. Control of embryonic motoneuron survival in vivo by ciliary neurotrophic factor. Science. 1991;251:1616–1618. doi: 10.1126/science.2011743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gould TW, Enomoto H. Neurotrophic modulation of motor neuron development. Neuroscientist. 2009;15:105–116. doi: 10.1177/1073858408324787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svoboda KR, Linares AE, Ribera AB. Activity regulates programmed cell death of zebrafish Rohon-Beard neurons. Development. 2001;128:3511–3520. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.18.3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanson MG, Landmesser LT. Normal patterns of spontaneous activity are required for correct motor axon guidance and the expression of specific guidance molecules. Neuron. 2004;43:687–701. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12•.Li H, de Faria JP, Andrew P, Nitarska J, Richardson WD. Phosphorylation regulates OLIG2 cofactor choice and the motor neuron-oligodendrocyte fate switch. Neuron. 2011;69:918–929. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.030. [This study identifies a postranslational modification of a transcription factor (TF) that regulates the switching of motor neuron phenotype to oligodendroglial differentiation. The phosphorylation of the TF Olig2 seems to be mediated by PKA although further studies are needed to confirm this result. This study pinpoints the presence of other factors that regulate the activity of TFs and hence the process of cell specification, after the TF combinatorial code has been established.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13••.Tripodi M, Stepien AE, Arber S. Motor antagonism exposed by spatial segregation and timing of neurogenesis. Nature. 2011;479:61–66. doi: 10.1038/nature10538. [This report shows that progenitor specification although necessary is not sufficient to determine the identity of different types of spinal interneurons involved in the motor circuitry. The timing when these cells are generated and the proprioceptive feedback contribute to discriminate between extensor and flexor premotor interneurons.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borodinsky LN, Root CM, Cronin JA, Sann SB, Gu X, Spitzer NC. Activity-dependent homeostatic specification of transmitter expression in embryonic neurons. Nature. 2004;429:523–530. doi: 10.1038/nature02518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15••.Marek KW, Kurtz LM, Spitzer NC. cJun integrates calcium activity and tlx3 expression to regulate neurotransmitter specification. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:944–950. doi: 10.1038/nn.2582. [This elegant work identifies a molecular mechanism by which Ca2+-mediated electrical activity regulates neurotransmitter specification in developing spinal neurons. The study shows that activity-responsive elements in the promoter of the transcription factor Tlx3 enable activity-dependent homeostatic switching between GABAergic and glutamatergic phenotypes.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16••.Belgacem YH, Borodinsky LN. Sonic hedgehog signaling is decoded by calcium spike activity in the developing spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4482–4487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018217108. [This study shows for the first time that there is an interplay between Ca2+-mediated electrical activity and Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling during spinal cord development. It identifies a novel signaling pathway for Shh action that is transcription-independent and leads to correlated IP3 and Ca2+ transients. In turn, this interaction allows Shh to extend its action on postmitotic neurons and to regulate neurotransmitter specification in an activity-dependent manner.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tallafuss A, Eisen JS. The Met receptor tyrosine kinase prevents zebrafish primary motoneurons from expressing an incorrect neurotransmitter. Neural Dev. 2008;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18•.Hale LA, Fowler DK, Eisen JS. Netrin signaling breaks the equivalence between two identified zebrafish motoneurons revealing a new role of intermediate targets. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025841. [This investigation determines that Netrin 1a secreted from the intermediate target induces two otherwise equivalent developing motor neurons to adopt different identities by preventing the axon of one of them from extending beyond the target muscle.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.Bradley S, Tossell K, Lockley R, McDearmid JR. Nitric oxide synthase regulates morphogenesis of zebrafish spinal cord motoneurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16818–16831. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4456-10.2010. [The authors identify a signaling molecule, nitric oxide, as a regulator of motor axon branching. In turn, this modulation of motor neuron morphology has a significant impact into the manifestation of developing locomotor behavior.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prithviraj R, Kelly KM, Espinoza-Lewis R, Hexom T, Clark AB, Inglis FM. Differential regulation of dendrite complexity by AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2 in motor neurons. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:247–264. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inglis FM, Crockett R, Korada S, Abraham WC, Hollmann M, Kalb RG. The AMPA receptor subunit GluR1 regulates dendritic architecture of motor neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8042–8051. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08042.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inglis FM, Zuckerman KE, Kalb RG. Experience-dependent development of spinal motor neurons. Neuron. 2000;26:299–305. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inglis FM, Furia F, Zuckerman KE, Strittmatter SM, Kalb RG. The role of nitric oxide and NMDA receptors in the development of motor neuron dendrites. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10493–10501. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10493.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Schessl J, Werner M, Bonnemann C, Xiong G, Mojsilovic-Petrovic J, Zhou W, Cohen A, Seeburg P, Misawa H, et al. Role of GluR1 in activity-dependent motor system development. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9953–9968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0880-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishiyama M, Togashi K, von Schimmelmann MJ, Lim CS, Maeda S, Yamashita N, Goshima Y, Ishii S, Hong K. Semaphorin 3A induces CaV2.3 channel-dependent conversion of axons to dendrites. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:676–685. doi: 10.1038/ncb2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanson MG, Landmesser LT. Increasing the frequency of spontaneous rhythmic activity disrupts pool-specific axon fasciculation and pathfinding of embryonic spinal motoneurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12769–12780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4170-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27••.Kastanenka KV, Landmesser LT. In vivo activation of channelrhodopsin-2 reveals that normal patterns of spontaneous activity are required for motoneuron guidance and maintenance of guidance molecules. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10575–10585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2773-10.2010. [This study extends the results of previous studies from the Landmesser lab and determines the parameters of spontaneous electrical activity in the developing spinal cord that are important for motor neuron axon guidance. Using expression of channelrhodopsin-2 the authors demonstrate that the frequency and normal pattern of Ca2+-mediated burst activity are necessary for the appropriate routing of motor neuron axons and the consequent innervation of matching target muscle.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dasen JS, Jessell TM. Hox networks and the origins of motor neuron diversity. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2009;88:169–200. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(09)88006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pineda RH, Svoboda KR, Wright MA, Taylor AD, Novak AE, Gamse JT, Eisen JS, Ribera AB. Knockdown of Nav1.6a Na+ channels affects zebrafish motoneuron development. Development. 2006;133:3827–3836. doi: 10.1242/dev.02559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saint-Amant L, Drapeau P. Synchronization of an embryonic network of identified spinal interneurons solely by electrical coupling. Neuron. 2001;31:1035–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saint-Amant L, Drapeau P. Motoneuron activity patterns related to the earliest behavior of the zebrafish embryo. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3964–3972. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-03964.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Personius KE, Karnes JL, Parker SD. NMDA receptor blockade maintains correlated motor neuron firing and delays synapse competition at developing neuromuscular junctions. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8983–8992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5226-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalez-Islas C, Wenner P. Spontaneous network activity in the embryonic spinal cord regulates AMPAergic and GABAergic synaptic strength. Neuron. 2006;49:563–575. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34••.Wilhelm JC, Rich MM, Wenner P. Compensatory changes in cellular excitability, not synaptic scaling, contribute to homeostatic recovery of embryonic network activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6760–6765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813058106. [This work shows that changes in electrical activity induce homeostatic changes in cell excitability that appear aimed at keeping levels of network activity constant in the developing spinal cord. Changes in GABAergic and AMPAergic synaptic strength are also apparent and contribute to the homeostatic changes, indicating that multiple mechanisms are in place to assure the constancy of this early electrical activity and underscoring its importance during spinal cord development.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fetcho JR, McLean DL. Some principles of organization of spinal neurons underlying locomotion in zebrafish and their implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1198:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLean DL, Fetcho JR. Spinal interneurons differentiate sequentially from those driving the fastest swimming movements in larval zebrafish to those driving the slowest ones. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13566–13577. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3277-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLean DL, Fan J, Higashijima S, Hale ME, Fetcho JR. A topographic map of recruitment in spinal cord. Nature. 2007;446:71–75. doi: 10.1038/nature05588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pineda RH, Ribera AB. Dorsal-ventral gradient for neuronal plasticity in the embryonic spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3824–3834. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0242-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Provine RR, Sharma SC, Sandel TT, Hamburger V. Electrical activity in the spinal cord of the chick embryo, in situ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970;65:508–515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.65.3.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40•.Li J, Walker SM, Fitzgerald M, Baccei ML. Activity-dependent modulation of glutamatergic signaling in the developing rat dorsal horn by early tissue injury. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:2208–2219. doi: 10.1152/jn.00520.2009. [This study demonstrates that environmental changes leading to increased afferent input during spinal cord development, such as a peripheral tissue injury, modulate excitatory synaptic drive onto developing spinal sensory neurons in an activity-dependent manner.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercer AR, Hildebrand JG. Developmental changes in the electrophysiological properties and response characteristics of Manduca antennal-lobe neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2650–2663. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.6.2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang SA, Campusano JM, Su H, O'Dowd DK. Drosophila mushroom body Kenyon cells generate spontaneous calcium transients mediated by PLTX-sensitive calcium channels. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:491–500. doi: 10.1152/jn.00096.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blanton MG, Lo Turco JJ, Kriegstein AR. Endogenous neurotransmitter activates N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors on differentiating neurons in embryonic cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:8027–8030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.8027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44••.Demarque M, Spitzer NC. Activity-dependent expression of Lmx1b regulates specification of serotonergic neurons modulating swimming behavior. Neuron. 2010;67:321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.006. [This remarkable study shows that spontaneous calcium spike activity in the hindbrain of developing Xenopus laevis larvae modulates the specification of serotonergic neurons via regulation of expression of the Lmx1b transcription factor. By using molecular and pharmacological approaches the authors demonstrate that the activity-dependent changes in serotonergic phenotype specification have an impact on the larval swimming behavior, highlighting the significant role of early electrical activity in the establishment of functional circuits.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dulcis D, Spitzer NC. Illumination controls differentiation of dopamine neurons regulating behaviour. Nature. 2008;456:195–201. doi: 10.1038/nature07569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang S, Polo-Parada L, Landmesser LT. Characterization of rhythmic Ca2+ transients in early embryonic chick motoneurons: Ca2+ sources and effects of altered activation of transmitter receptors. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15232–15244. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3809-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Donovan MJ, Wenner P, Chub N, Tabak J, Rinzel J. Mechanisms of spontaneous activity in the developing spinal cord and their relevance to locomotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;860:130–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feller MB, Wellis DP, Stellwagen D, Werblin FS, Shatz CJ. Requirement for cholinergic synaptic transmission in the propagation of spontaneous retinal waves. Science. 1996;272:1182–1187. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong RO, Meister M, Shatz CJ. Transient period of correlated bursting activity during development of the mammalian retina. Neuron. 1993;11:923–938. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singer JH, Mirotznik RR, Feller MB. Potentiation of L-type calcium channels reveals nonsynaptic mechanisms that correlate spontaneous activity in the developing mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8514–8522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08514.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bansal A, Singer JH, Hwang BJ, Xu W, Beaudet A, Feller MB. Mice lacking specific nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits exhibit dramatically altered spontaneous activity patterns and reveal a limited role for retinal waves in forming ON and OFF circuits in the inner retina. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7672–7681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07672.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Torborg CL, Hansen KA, Feller MB. High frequency, synchronized bursting drives eye-specific segregation of retinogeniculate projections. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:72–78. doi: 10.1038/nn1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McLaughlin T, Torborg CL, Feller MB, O'Leary DD. Retinotopic map refinement requires spontaneous retinal waves during a brief critical period of development. Neuron. 2003;40:1147–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00790-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Penn AA, Riquelme PA, Feller MB, Shatz CJ. Competition in retinogeniculate patterning driven by spontaneous activity. Science. 1998;279:2108–2112. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5359.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cancedda L, Fiumelli H, Chen K, Poo MM. Excitatory GABA action is essential for morphological maturation of cortical neurons in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5224–5235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5169-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang CL, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Zhou J, Yang XJ, Duan SM, Xiong ZQ, Ding YQ. Activity-dependent development of callosal projections in the somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11334–11342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3380-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57••.De Marco Garcia NV, Karayannis T, Fishell G. Neuronal activity is required for the development of specific cortical interneuron subtypes. Nature. 2011;472:351–355. doi: 10.1038/nature09865. [This report demonstrates that migration and neurite development of subtypes of cortical GABAergic interneurons depend on early neuronal activity and glutamate-mediated signaling in mice. They identified the engulfment and cell motility 1 gene as the molecular target for the activity-dependent interneuron migration.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]