Abstract

Introduction

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) has been associated with dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in non-pregnant samples. However, it is not yet known whether CSA is associated with HPA dysregulation over pregnancy. In the present study we assessed whether maternal cortisol levels across pregnancy differed in women with CSA histories compared to women with histories of non-sexual child abuse (CA) and no abuse (NA).

Methods

135 pregnant mothers (CSA=30, CA=58, NA=47) provided salivary cortisol samples at wakeup, wake +30 minutes, and bedtime for 3 consecutive days at 1–3 time points over second and third trimester. Cortisol awakening responses and slopes were computed.

Results

Women with CSA histories displayed increasing cortisol awakening response over pregnancy compared to women with CA and NA histories. Group differences were not observed for slope.

Conclusions

This is the first study to show that cortisol awakening responses increase over pregnancy in women with CSA histories compared to women with CA and NA histories.

Keywords: child abuse, cortisol, cortisol awakening response, cortisol slope, pregnancy

Pregnant women who were sexually abused as children are more likely to be hospitalized, have premature contractions, and to give birth preterm compared to women without abuse histories (Van Der Leden & Raskin, 1993; Noll et al., 2007; Leeners, Richter-Appelt, Imuthurn, et al. 2006; Leeners, Stiller, Block, et al. 2010). Previous research has posited that one mechanism linking childhood sexual abuse (CSA) to poor neonatal outcomes may be dysregulated maternal cortisol levels during pregnancy (Noll, et al., 2007).

Over typical pregnancies, total maternal salivary cortisol output increases due to the release of corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) by the developing placenta, while the diurnal cortisol rhythm is preserved (de Weerth & Buitelaar, 2005). In addition, cortisol reactivity to stress is blunted (Brunton, 2010), and the cortisol awakening response declines (Entringer et al., 2010) as pregnancy progresses. Changes in these typical patterns, including cortisol awakening responses that fail to decline, exaggerated increases in total cortisol output over pregnancy, and higher maternal placental CRH in third trimester, have been associated with poor neonatal outcomes and infant temperament, including younger gestational age at birth, lower birth weight, and negative infant reactivity (Wadhwa et al., 2004; Davis et al., 2007; Buss et al., 2009; Goedhart et al., 2010; Bolten et al., 2011). Given associations between dysregulation of maternal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) activity and adverse neonatal outcomes, dysregulated maternal cortisol is a plausible mechanism linking maternal history of CSA to poor neonatal outcomes.

In non-pregnant samples, history of CSA has been associated with HPA dysregulation across a number of studies; however, direction of effects has differed between studies. Specifically, CSA has been associated with both lower and higher daily cortisol secretion (Lemieux & Coe, 1995; Bremner et al., 2003; Cicchetti, Rogosch, Gunnar et al., 2010; Nicolson, Davis, Kruszewski et al., 2010). CSA has been associated with greater cortisol awakening responses (Weissbecker, Floyd, Dedert et al., 2006; Mondelli et al., 2010), blunted cortisol responses to exogenous hormone challenge (De Bellis et al., 1994; Stein, Yehuda, Koverola et al., 1997), and blunted response to lab stress paradigms (Pierrehumbert et al., 2009). However, no studies have examined the association between maternal history of CSA and maternal cortisol levels over pregnancy. Only one study has examined the effects of childhood trauma on cortisol in pregnancy. She a and colleagues reported that pregnant women with histories of childhood trauma had lower morning cortisol values at ~28 weeks gestation compared to pregnant women without abuse histories (Shea et al., 2007). However, this study did not examine the specific effects of child sexual abuse on maternal cortisol, nor did it examine associations between childhood trauma and change in cortisol over pregnancy.

Taken together, it is not yet known: 1) whether CSA predicts patterns of maternal cortisol secretion over pregnancy, or 2) whether childhood trauma in general, or child sexual abuse in particular, predicts patterns of cortisol secretion over pregnancy. Utilizing a diverse, low-income perinatal sample, this study examined whether cortisol patterns over pregnancy differ in women with CSA histories versus women with a history of non-sexual child abuse (CA) or no child abuse (NA) history.

Methods

Participants

Participants were part of an ongoing study of the effects of maternal depression on fetal and infant development. Participants were recruited throughout pregnancy (8–38 weeks gestation). Seven hundred and ninety-three pregnant women volunteered to participate in the larger study, 359 met eligibility criteria, and 155 had enrolled at the time of the present analyses. Of these, 145 women completed both child abuse and maternal cortisol measures. We then excluded 10 women due to emerging gestational diabetes/insulin use, steroid use, and/or delivered prior to the final cortisol sampling window (~35 weeks gestation), leaving 135 pregnant women included in the current analyses (ages 18–40, Mage= 26 (SD=6)). The sample was racially and ethnically diverse (42% Non Hispanic White, 23% Hispanic, 14% Non Hispanic Black, 12% more than one race, 5% Asian, 4% ‘other’), predominantly low income (M=$30–39K/year), and the majority of pregnancies were unplanned (59%). See Table 1. This study was approved by the Women and Infants Hospital IRB.

Table 1.

Maternal Demographics by Maternal Child Abuse Group.

| Child Sexual Abuse (n = 30) |

Child Abuse (n = 58) |

No Child Abuse (n = 47) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | Median (range) | Median (range) | ||

| Physical Abuse | 3 (0–10) | 3 (0–12) | 0 (0–0) | |

| Domestic Violence | 0 (0–8) | 0 (0–12) | 0 (0–0) | |

| Physical Neglect | 0 (0–6) | 0 (0–7) | 0 (0–0) | |

| Sexual Abuse | 3 (1–12) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | |

| Maternal age (years) | 27 (6) | 26 (6) | 27 (6) | .77 |

| Race (% Non Hispanic White) | 41% | 45% | 40% | .34 |

| Marital Status (% married) | 36% | 31% | 42% | .31 |

| Yearly Income1 | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 5 (3) | .50 |

| Body Mass Index | 30 (8) | 25 (6) | 25 (7) | .003 |

| Parity (median, range) | 1 (0–3) | 0 (0–5) | 1 (0–4) | .73 |

| Gravida (median, range) | 1 (0–5) | 1 (0–8) | 1 (0–5) | .93 |

| Planned pregnancy (% no) | 69% | 63% | 63% | .82 |

| Drinks over pregnancy | 12 (24) | 9 (11) | 4 (10) | .31 |

| Cigarette Smokers (% yes) | 10% | 22% | 14% | .42 |

| Depressive symptoms (IDS)2 | 14 (12) | 14 (8) | 12 (10) | .80 |

| Anxiety symptoms (HAM-A)3 | 8 (6) | 6 (4) | 6 (4) | .04 |

| Perceived Stress Score (12 item) | 25 (9) | 24 (8) | 22 (9) | .54 |

| Lifetime PTSD diagnosis4 | 4% | 3% | 2% | .17 |

Total yearly income. 1=<$5000 to 8=>$100,000; 5=$30,000–39,000.

Scores > 36 indicate severe symptoms of depression.

Scores > 24 indicate severe symptoms of anxiety.

Assessed by SCID.

Procedure

Participants completed 1–3 study sessions over the 2nd and 3rd trimesters of pregnancy (Session 1: Mweeks= 24 (range: 20–26); Session 2: Mweeks= 30 (range: 27–32), Session 3: Mweeks= 35 (range: 33–38)). 100% of women completed at least 1 study session, 84% completed at least 2 study sessions, and 67% completed all 3 study sessions. At their first session, participants reported on child abuse experiences, perceived stress, depression and anxiety symptoms, and cigarette and alcohol consumption (See Measures). For three days following each session, participants were instructed to provide salivary cortisol samples (passive drool) at wake-up, +30 minutes, and bedtime. Protocol compliance was assessed on a subset of participants (6%) via Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) caps (AARDEX, Zurich, Switzerland) (r’s=0.99–1.0, and 0.87–1.0 for associations between self-reported and MEMS sampling times for wake/wake + 30, and bedtime samples, respectively).

Measures

Child Abuse

Participants completed a self-report measure of childhood abuse experiences comprised of 15 items from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale (Dube et al., 2003). Participants reported on childhood sexual abuse (4 items), physical abuse (4 items), domestic violence (4 items), and physical neglect (3 items) prior to age 18. Response options ranged from 0=never to 4=very often. Participants were categorized into three groups: ‘No Abuse (NA),’ ‘Non-sexual Abuse (CA)’ and ‘Sexual abuse (CSA).’ The CSA group included women with CSA who either did (N=23) or did not (N=7) also endorse other forms of child abuse. The CA group included women who endorsed any child abuse experiences other than sexual abuse. The NA group included women who denied any child abuse.

Maternal salivary cortisol

Saliva samples were frozen and shipped to Dresden University for analysis. Cortisol concentrations were analyzed in duplicate with an immunoassay with time-resolved fluorescence detection. The intra and inter-assay coefficients of variation were < 8%.

Covariates

As part of the larger study, participants provided their age, race, marital status, parity, gravida, and yearly household income. Participants reported their pre-pregnancy height and weight to compute body mass index (BMI). Lifetime post-traumatic stress disorder was assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis (SCID-IV). At all study sessions, participants reported any physical illness including gestational diabetes, hypertension, or preeclampsia. Participants completed self-report measures of depressive symptoms (Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS); scores > 36 indicate severe symptoms; (Rush et al., 1986)), anxiety symptoms (Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS); scores > 24 indicate severe symptoms; (Hamilton, 1959)), and stress (Perceived Stress Scale; (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). At all study sessions, alcohol and cigarette consumption was quantified using Timeline Follow-Back interview (Sobell, Brown, Leoet al., 1996). Participants were considered ‘smokers’ if they smoked any cigarettes over pregnancy.

Data Analysis

For each day of cortisol collection, CARs were calculated by computing the difference in the morning samples, and slope was computed by calculating the difference between the morning and evening samples and dividing by the time interval between awakening and bedtime. CARs and slopes were then averaged across days for each study session. Morning saliva samples that were <20 or >40 minutes apart, and outliers +/− 4 standard deviations, were identified. Because neither patterns nor significance of results were altered when these samples were omitted, all samples were included in final analyses. Time of awakening was included as a covariate in CAR analyses. CAR and slope values were not significantly skewed and therefore values were not log transformed.

Data were analyzed using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) techniques. Two level models were performed in which, at level-1, a set of slopes for each individual was generated that reflected variations in cortisol (CAR, slope) as a function of gestational age (in weeks), and at level-2, it was determined whether childhood abuse groups (and covariates) explained variance in slopes in the level-1 models. Full maximum likelihood and robust standard errors were used to estimate all models. HLM analyses do not require that participants complete assessments on the same schedule, nor do they require an equal number of observations per participant. Thus analyses were not affected by discrepancies in the timing of study sessions over gestation.

Results

30 participants reported CSA, 58 reported CA, and 47 participants reported NA. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests were utilized to assess for significant group differences in demographic or psychosocial variables (see Table 1). Women with CSA histories showed significantly higher pre-pregnancy BMI (F(2,133)= 6.01, p=.003) and greater anxiety symptoms (F(2,133)= 3.37, p=.04) than CA and NA groups. Thus, BMI and anxiety symptoms were included as covariates. No other group differences were found, nor were any demographic or psychosocial variables significantly associated with cortisol outcomes.

Prior to examining group differences in cortisol patterns over pregnancy, we assessed for changes in CAR and slope across pregnancy for the entire sample. Consistent with typical cortisol patterns over pregnancy in prior studies, women in the study showed decreasing CAR (Mchange=−1.77, SD=12.57) while the diurnal rhythm was preserved (slope: Mchange=0.23, SD=1.35) across pregnancy (change between first and final study session). There was no significant main effect of gestation (in weeks) on cortisol values at wake-up (b=.001, SE=.001, p=.55) or +30 minutes (b=−.001, SE=.001, p=.84). However, there was a main effect of gestation (in weeks) on cortisol values at bedtime (b=.02, SE=.002, p<.001), such that women showed increasing evening cortisol values over pregnancy.

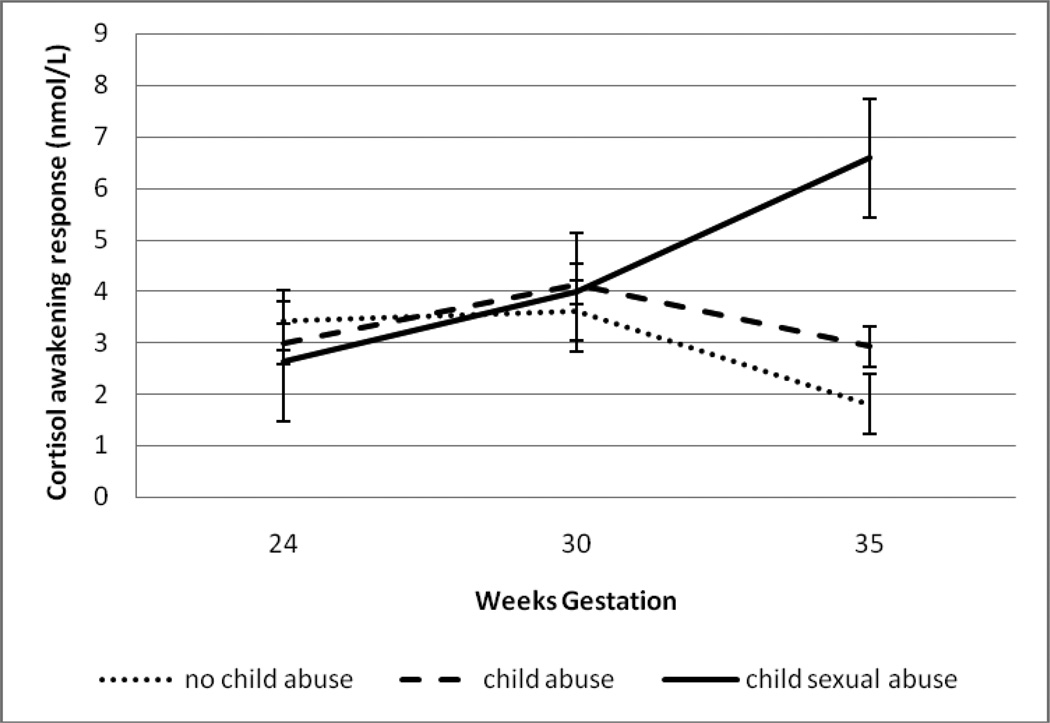

HLM analyses revealed that within-person changes in CAR across gestation were significantly moderated by maternal child abuse group (b=.13, SE=.07, p=.04). See Figure 1. Post-hoc analyses revealed that women with CSA histories had significantly higher CARs at 35 weeks compared to women with CA or NA histories (F(2,81)= 5.35, p=.009). See Table 2. Within-person changes in slope across gestation were not significantly moderated by child abuse group (b=.04, SE=.03, p=.18). There were no significant effects of child abuse group status on change in cortisol at wake-up (b=.001, SE=.002, p=.35), +30 minutes (b=.001, SE=.001, p=.33) or bedtime (b=.001, SE=.003, p=.84) across gestation.

Figure 1. Maternal child abuse predicts cortisol awakening response over gestation.

Mean cortisol awakening responses for women with CSA histories (N= 30), CA histories (N= 58), and NA histories (N=47) at 24, 30, and 35 weeks gestation.

Table 2.

Maternal Cortisol by Maternal Child Abuse Group

| Child Sexual Abuse (n = 30) |

Child Abuse (n = 58) |

No Child Abuse (n = 47) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | |

| Cortisol Awakening Response (nmol/L) | ||||

| 24 weeks (n=97)1 | 2.63 (1.15) (1)2 | 2.97 (0.98) (2) | 3.44 (1.09) (3) | .20 |

| 30 weeks (n=100) | 3.98 (1.89) (1) | 4.13 (1.95) (0) | 3.62 (0.98) (7) | .34 |

| 35 weeks (n=99) | 6.58 (1.02) (1) | 2.92 (.92) (2) | 1.80 (1.13) (0) | .009 |

| Cortisol Slope (nmol/L) | ||||

| 24 weeks (n=91) | −.93 (.52) (6) | −.99 (.76) (27) | −.85 (1.25) (13) | .81 |

| 30 weeks (n=60) | −1.00 (.61) (13) | −1.24 (.58) (28) | −.85 (.63) (22) | .12 |

| 35 weeks (n=90) | −.16 (2.33) (7) | −.81 (.52) (27) | −.76 (.63) (13) | .13 |

n = number of cortisol values included in analyses per study session.

Number of missing cortisol values.

Discussion

In this ethnically diverse, low-income sample of primarily unplanned pregnancies, we found that women with child sexual abuse histories displayed increasing cortisol awakening response (CAR) across gestation compared to women with non-sexual child abuse histories or women who had never experienced abuse. Significant group differences were observed only at the end of the 3rd trimester. We did not observe group differences in slope over pregnancy, suggesting that women with sexual abuse histories exhibit greater CAR in the absence of differences in diurnal cortisol.

Results from this study may have implications for neonatal outcomes and infant development. Previous studies have reported that higher maternal cortisol in late second/early third trimester (Mazor et al., 1994; Erickson et al., 2001) and higher maternal placental CRH at in early third trimester (Wadhwa, et al., 2004) were related to shorter gestational length and fetal growth restriction. As well, elevated maternal cortisol in third trimester was related to greater cortisol and behavioral stress reactivity in 1-day-old infants (Davis, et al., 2007). Taken together, greater third trimester CAR in CSA women may serve as a mechanism linking CSA to poor neonatal and infant outcomes.

We can articulate several possible explanations for our finding that women with sexual abuse histories display increasing CAR over pregnancy, with group differences emerging in third trimester. One possibility is that results represent biological differences in regulation of the HPA axis between child abuse groups. Findings from previous studies have shown a pattern of increasing hypo-responsiveness of the HPA reactivity to stress over gestation (Entringer, et al., 2010). It is believed that this period of HPA quiescence as parturition approaches serves to protect the fetal brain from negative influences of maternal glucocorticoids (de Kloet, Rosenfeld, van Eekelen et al., 1988). In other developmental periods in which the HPA axis is typically hypo-responsive to stress (e.g., late infancy through childhood), which are also believed to be brain-protective, previous studies have found that children who experience dearly adversity did not exhibit the protective hypo-responsive profile (Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007). Similarly, our results suggest that mothers exposed to child sexual abuse also do not show the protective shift to hypo-responsiveness over pregnancy. Furthermore, release from potentially protective maternal HPA hypo-responsiveness may then impact the next generation through exposure to heightened cortisol during a critical period of brain maturation, and may also lead to poor neonatal outcomes as hormones of the HPA axis have been implicated in premature labor and delivery (Wadhwa, et al., 2004; Buss, et al., 2009; Entringer, Buss, Andersen et al., 2011).

A second possibility is that child abuse group differences in maternal HPA regulation originate from the fetal/placental unit (Entringer, et al., 2010; Wadhwa, Entringer, Buss, & Lu, 2011). Previous research has found a sharp increase in CRH and decrease in CRH-binding protein (which regulates availability of biologically active CRH) 2–4 weeks prior to delivery (McLean et al., 1995). As well, past research has found that, at 27–37 weeks gestation, levels of CRH-binding protein were lower, and serum cortisol levels were higher, in women that went on to deliver preterm (Erickson, et al., 2001). Thus, greater CAR in late third trimester for women with child sexual abuse histories may have been driven by earlier onset of spontaneous labor in these women.

A third explanation is that results are driven by behavioral differences between groups. For example, it is possible that mothers with child sexual abuse histories experience more disrupted sleep and greater stress late in pregnancy relative to mothers with no history of sexual abuse. In support of behavioral explanations, we found differences in CAR but not cortisol slope between groups. According to previous research, CAR and slope provide different information on HPA axis functioning. More specifically, the CAR appears to be superimposed upon the circadian cycle and is related to sleep quality, whereas slope provides information on diurnal functioning of the HPA axis (Wilhelm, Born, Kudielka et al., 2007). A recent review reported that sleep disturbances are greater in victims of sexual abuse compared to non-abused individuals (Steine et al., 2011). As well, sleep deprivation in pregnancy has been associated with poor fetal outcomes, including preterm birth (Chang, Pien, Duntley et al., 2010). Thus, sleep disturbances may explain differences in CAR in women with sexual abuse histories and may place women at increased risk for adverse neonatal outcomes.

Past studies have also reported that women with sexual abuse histories experience greater stress in pregnancy, including experiencing more pregnancy complications (Leeners, et al., 2010) and reporting more worry about the baby’s health during pregnancy (Eide, Hovengen, & Nordhagen, 2010) compared to non-abused women. Increasing stress over gestation in women with child sexual abuse histories would be in contrast to decreasing perceived stress found in non-abused pregnant women (Entringer, et al., 2010), and therefore may partially explain differences in CAR. Future research is needed to replicate these findings and to delineate biological and behavioral mechanisms leading to altered CAR during third trimester in mothers with histories of child sexual abuse.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine associations between child sexual abuse and maternal cortisol across pregnancy. However, the study has several limitations. Child abuse was measured retrospectively and we did not measure perceived severity of abuse. In addition, there was heterogeneity in abuse experiences of women in the child sexual and non-sexual abuse groups. Future studies are needed in order to examine effects of child sexual abuse on cortisol over pregnancy independent of other forms of abuse. This could be accomplished by matching participants according to abuse experiences (with the exception of sexual abuse in the child sexual abuse group). We also did not assess whether CAR served as a mechanism linking child sexual abuse to poor neonatal outcomes, given that the larger ongoing study was comprised of primarily healthy births, and because the sampling protocol excluded women who delivered prior to 35 weeks gestation. As well, we collected only three cortisol samples per day in order to minimize participant burden in this pregnant sample, and only a sub sample of participants were given MEMS caps to verify the timing of saliva samples. In addition, a small percentage of women completed only one study visit and thus for these women we were unable to evaluate their change in cortisol over gestation. Finally, we did not collect information on daily factors known to influence cortisol values, such as daily stress, sleep, and mood.

While findings from this study are preliminary due to the ongoing nature of the study and because the larger study was not designed to investigate effects of child sexual abuse on HPA activity, results suggest that mothers with sexual abuse histories show alterations in HPA regulation (higher late-pregnancy CAR) versus mothers with without sexual abuse histories. Given links between maternal HPA dysregulation (including non-declining CAR over pregnancy) and risk for poor neonatal outcomes in prior studies, altered CAR in mothers with a history of sexual abuse may increase risk for poor neonatal and infant outcomes, including preterm birth, low birth weight, and negative behavioral and biological reactivity in infants (Davis, et al., 2007; Buss, et al., 2009; Goedhart, et al., 2010). More research is needed in order to understand the biological and psychological processes that may explain child abuse group differences in CAR over pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

Role of the Funding Source

Funding for this study was provided by NIMH (MH079153). NIMH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Dr. Margaret Bublitz managed the literature searches, undertook the statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

Dr. Laura Stroud designed the study and wrote the protocol.

All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- Bolten MI, Wurmser H, Buske-Kirschbaum A, Papousek M, Pirke KM, Hellhammer D. Cortisol levels in pregnancy as a psychobiological predictor for birth weight. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2011;14:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00737-010-0183-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunton PJ. Resetting the dynamic range of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis stress responses through pregnancy. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2010;22(11):1198–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Entringer S, Reyes JF, Chicz-DeMet A, Sandman CA, Waffarn F, Wadhwa PD. The maternal cortisol awakening response in human pregnancy is associated with the length of gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(4):398, e391–e398. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JJ, Pien GW, Duntley SP, Macones GA. Sleep deprivation during pregnancy and maternal and fetal outcomes: Is there a relationship? Sleep Medicine Review. 2010;14(2):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EP, Glynn L, Dunkel-Schetter C, Hobel C, Chicz-DeMet A, Sandman CA. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression and cortisol influences infant temperament. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(6):737–746. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318047b775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Rosenfeld P, van Eekelen JA, Suntanto W, Levine S. Stress, glucocorticoids, and development. Prog Brain Res. 1988;73:101–120. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weerth C, Buitelaar JK. Cortisol awakening response in pregnant women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(9):902–907. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):564–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide J, Hovengen R, Nordhagen R. Childhood abuse and later worries about the baby's health in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(12):1523–1531. doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.526180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entringer S, Buss C, Andersen J, Chicz-DeMet A, Wadhwa PD. Ecological momentary assessment of maternal cortisol profiles over a multiple-day period predicts the length of human gestation. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:469–474. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31821fbf9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entringer S, Buss C, Shirtcliff EA, Cammack AL, Yim IS, Chicz-DeMet A, Wadhwa PD. Attenuation of maternal psycho physiological stress responses and the maternal cortisol awakening response over the course of human pregnancy. Stress. 2010;13(3):258–268. doi: 10.3109/10253890903349501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson K, Thorsen P, Chrousos GP, Grigoriadis DE, Khongsaly O, McGregor J, Schulkin J. Preterm Birth: Associated neuroendocrine, medical, and behavioral risk factors. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86(6) doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedhart G, Vrijkotte TG, Roseboom TJ, van der Wal MF, Cuijpers P, Bonsel GJ. Maternal cortisol and offspring birth weight: results from a large prospective cohort study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(5):644–652. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Quevedo K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32(1):50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeners B, Richter-Appelt H, Imuthurn B, Rath W. Influence of childhood sexual abuse on pregnancy, delivery, and the early postpartum period in adult women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeners B, Stiller R, Block E, Gorres G, Rath W. Pregnancy complications in women with childhood sexual abuse experiences. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010;69:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazor M, Chaim W, Hershkowitz R, Levy J, Leiberman JR, Glezerman M. Association between preterm birth and increased maternal plasma cortisol concentrations. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84(4):521–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean M, Bisits A, Davies J, Woods R, Lowry P, Smith RA. A placental clock controlling the length of human pregnancy. Nature Medicine. 1995;1:460–463. doi: 10.1038/nm0595-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll J, Schulkin J, Trickett PK, Susman EJ, Breech L, Putnam FW. Differential pathways to preterm delivery for sexually abused and comparison women. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(10):1238–1248. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Giles DE, Schlesser MA, Fulton CL, Weissenburger J, Burns C. The Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res. 1986;18(1):65–87. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea AK, Streiner DL, Fleming A, Kamath MV, Broad K, Steiner M. The effect of depression, anxiety, and early life trauma on the cortisol awakening response during pregnancy: Preliminary results. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell IC, Brown J, Leo GI, Sobell MB. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steine IM, Harvey AG, Krystal JH, Milde AM, Gronli J, Bjorvatn B, Pallesen S. Sleep distrubances in sexual abuse victims: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Review. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Leden ME, Raskin VD. Psychological Sequelae of childhood sexual abuse: relevant in subsequent pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Scandinavia. 1993;168(4):1336–1337. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa PD, Entringer S, Buss C, Lu M. The contribution of maternal stress to preterm birth: Issues and considerations. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38:351–384. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa PD, Garite TJ, Porto M, Glynn L, Chicz-DeMet A, Dunkel-Schetter C, Sandman CA. Placental corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), spontaneous preterm birth, and fetal growth restriction: A prospective investigation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191(4):1063–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm I, Born J, Kudielka BM, Schlotz W, Wust S. In the cortisol awakening rise a response to awakening? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(4):358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]