Abstract

There is considerable evidence linking substance use and delinquent behavior among adolescents. However, the nature and temporal ordering of this relationship remains uncertain, particularly among early adolescents and those with significant psychopathology. This study examined the temporal ordering of substance use and delinquent behavior in a sample of psychiatrically hospitalized early adolescents. Youth (n = 108) between the ages of 12 and 15 years completed three assessments over 18 months following hospitalization. Separate cross-lagged panel models examined the reciprocal relationship between delinquent behavior and two types of substance use (e.g., alcohol and marijuana). Results provided evidence of cross-lagged effects for marijuana: delinquent behavior at 9 months predicted marijuana use at 18 months. No predictive effects were found between alcohol use and delinquent behavior over time. Findings demonstrate the stability of delinquent behavior and substance use among young adolescents with psychiatric concerns. Furthermore, results highlight the value of examining alcohol and marijuana use outcomes separately in order to better understand the complex pathways between substance use and delinquent behavior among early adolescents.

Keywords: adolescents, alcohol, marijuana, delinquent behavior, cross-lagged panel modeling

1. Introduction

There is considerable evidence linking substance use and delinquency among adolescents (D'Amico, Edelen, Miles, & Morral, 2008; Doherty, Green, & Ensminger, 2008; Hayatbakhsh et al., 2008; Wanner, Vitaro, Carbonneau, & Tremblay, 2009). While there are clear associations between these problem behaviors, their development and temporal ordering remains uncertain and may vary over the course of adolescence (Doherty, et al., 2008; Marmorstein, Iacono, & Malone, 2010; Mason & Windle, 2002). Understanding the onset and temporal ordering of these co-occurring problems is particularly important among younger adolescents with psychiatric problems, since these youth experience elevated risk of developing both substance use and delinquency (Armstrong & Costello, 2002; King, Iacono, & McGue, 2004; Steiner & Cauffman, 1998; Teplin et al., 2005). Furthermore, few studies have separately investigated the longitudinal association for alcohol and marijuana use, despite evidence that patterns of adolescent use vary by type of substance (Flory, Lynam, Milich, Leukefeld, & Clayton, 2004; Kosterman, Hawkins, Guo, Catalano, & Abbott, 2000). Thus, the goal of this study was to separately examine the longitudinal relationship between delinquency and alcohol and marijuana use, respectively, in a sample of psychiatrically hospitalized early adolescents, aged 12 to 15 years.

Numerous studies have provided evidence that delinquent behavior leads to increased substance use (Doherty, et al., 2008; Hayatbakhsh, et al., 2008; Wanner, et al., 2009). Two separate longitudinal investigations of middle-school students found that deviant behavior is a positive predictor of subsequent initiation of marijuana use (Henry, Thornberry, & Huizinga, 2009; van den Bree & Pickworth, 2005). In addition, a 5-year study of 429 youth demonstrated that increased delinquency at age 11 predicted increased alcohol use at age 16 for both boys and girls (Mason, Hitchings, & Spoth, 2007). Another study of high school students found that more frequent delinquent behavior in grade 10 was associated with greater problem substance use in grade 12, while substance use in grade 10 was not associated with delinquent behavior in grade 12 (Bui, Ellickson, & Bell, 2000). A prevailing theory to account for this relationship is that delinquent behavior provides both a peer group and social context that increases the propensity toward substance use (D'Amico, et al., 2008; van den Bree & Pickworth, 2005).

Conversely, other community studies have provided data indicating that substance use predicts delinquent behavior (Ford, 2005; French, 2003; Loeber & Farrington, 2000). For instance, Huang and colleagues (2001) followed fifth-graders for eight years and examined the reciprocal association between alcohol use and interpersonal aggression. Results indicated that alcohol use at age 16 predicted interpersonal aggression at age 18, whereas aggression did not exert any predictive effects on subsequent alcohol use. Another longitudinal study of high school age students by Ford and colleagues (2005) found that marijuana use predicted later delinquent behavior, but delinquency did not predict later marijuana use. Investigators have proposed several mechanisms by which substance use leads to delinquent behavior including the acute effects of intoxication (Parker, 1998), the need to obtain resources to support substance use (Goldstein & Herrera, 1995), and the weakening of prosocial bonds (Ford, 2005).

At least one study of adolescents in the community and two studies of juvenile detainees have found evidence of a bi-directional relationship between delinquent behavior and substance use (D'Amico, et al., 2008; Dembo et al., 2002; Mason & Windle, 2002). Mason and Windle (2002) examined reciprocal associations between substance use and delinquency in high school students over a two-year period. They found that delinquency predicted substance use at each of the four follow-up waves, and that substance use predicted delinquency from time 1 to time 2. Of note, these results were significant for boys but not girls. In a study of high-school aged juvenile detainees, Dembo and colleagues (2002) found two significant cross-lagged associations across three time points: delinquent behaviors at baseline predicted substance use at 12 months, and substance use at 12 months predicted delinquent behaviors at 24 months. These results provided indication of bi-directional influences, but did not support a consistent reciprocal association over the follow-up period. More recently, D’Amico and colleagues (2008) investigated the relationship between substance use and delinquency among 449 juvenile offenders aged 13 to 17 years. Cross-lagged panel modeling indicated that adolescent substance use and delinquent behavior had significant bi-directional effects at each time point (e.g., baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months), suggesting that the reciprocal relationship was fairly stable over time.

In addition to producing mixed results, prior longitudinal studies have been subject to several limitations. First, studies have predominantly focused on adolescents in community samples (Bui, et al., 2000; Ford, 2005; Henry, et al., 2009; Mason & Windle, 2002) or those involved in the juvenile justice system (D'Amico, et al., 2008; Dembo, et al., 2002). To date, no studies have examined the longitudinal relationship in a sample of adolescents presenting for mental health treatment, despite the fact that these youth are at increased risk for both substance use and delinquent behavior (Armstrong & Costello, 2002; King, et al., 2004; Steiner & Cauffman, 1998; Teplin, et al., 2005). In addition to occurring at higher rates, it is possible that these behaviors have different stability and reciprocal effects among adolescents presenting for mental health treatment. Following a clinical sample of adolescents could elucidate this relationship and provide information about post-intervention processes, which could, in turn, inform further treatment development and enhancement.

Second, prior investigations have typically examined only alcohol use (Huang et al., 2001; Mason et al., 2007), only marijuana use (Ford, 2005; Henry, et al., 2009; van den Bree & Pickworth, 2005) or have created a composite measure of substance use (D'Amico, et al., 2008; Mason & Windle, 2002). Yet, studies suggest that trajectories of adolescent substance use vary by the type of substance (Flory, et al., 2004; Martino, Ellickson, & McCaffrey, 2008). For instance, Kosterman and colleagues (2000) separately examined the initiation of alcohol and marijuana use in a community sample, and found significant differences in the slopes of the initiation trajectories over an eight year period. Specifically, the slope of the initiation trajectory for alcohol use peaked prior to the age of 13 and then slowly declined, whereas the slope of the initiation trajectory for marijuana use remained relatively stable throughout adolescence.

Finally, studies with non-community samples (e.g., juvenile detainees) have predominantly included older adolescents (D’Amico et al., 2008; Dembo et al., 2002). Studies focused on younger adolescents could offer information about the early development and interrelationship between these problem behaviors. This is particularly beneficial considering that early initiation of substance use has been associated with a range of deleterious outcomes including later substance dependence, Axis II comorbidity, and criminal involvement (Anthony & Petronis, 1995; Franken & Hendriks, 2000).

The current study aimed to address the aforementioned limitations by examining the longitudinal association between substance use and delinquency among younger adolescents, aged 12 to 15 years, following hospitalization for psychiatric concerns. Our primary hypothesis was that delinquent behavior and frequency of substance use would have reciprocal effects over the 18 months following hospitalization. Consistent with prior studies (Dembo et al., 2002; Ford, 2005), our secondary hypothesis was that both delinquent behavior and substance use would demonstrate significant stability over time. To extend prior research, we separately examined the longitudinal relationship between delinquency and frequency of use for the two most commonly abused substances among adolescents: alcohol and marijuana.

2. Methods

2.1 Procedures and Participants

The research methods used in this study have been described in a prior publication (Prinstein et al., 2008). Participants in the initial study were 143 psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents between the ages of 12 and 15 years. Adolescents were recruited from a psychiatric inpatient facility in the northeastern United States between 2001 and 2005. All adolescents admitted to the unit were eligible for study participation, provided that they had no clinically evident cognitive impairment which would preclude completing a structured interview (e.g., no active psychosis or mental retardation). Participation involved completion of a comprehensive assessment battery at baseline and up to five follow-up sessions.

Over the recruitment period, a total of 246 adolescents matching the study inclusion criteria were admitted to the unit. At the time of data collection, about 40% of all admissions were discharged or transferred within 1–2 days. This short treatment duration was due to a variety of factors (e.g., vacancies at local facilities, insurance specifications) and did not serve as an indicator of diagnostic severity or socio-economic status. Consistent with approved human ethics procedures, adolescents were approached for the study after clinical personnel had gained permission from the parent/guardian, typically on the second day following admission. Consent was requested from 183 adolescents who were identified as eligible prior to discharge. A total of 162 (88.5%) provided consent, and 143 of these (88.3%) remained on the unit long enough to complete the intake battery. The current analysis includes 108 adolescents who completed the baseline substance use measures. Administration of the substance use measure commenced after study recruitment was underway, and these data were not collected for the first 35 adolescents.

Participants in the final sample were predominantly female (68%) and Caucasian (7%), with modest representation of adolescents identifying as Hispanic (6%) or Other/Multiracial (14%). The average age was 13.5 years (SD = .74). About 31% of adolescents lived with only their biological mother, 21% lived with both biological parents, 19% lived with a biological mother and stepparent, and the remaining youth lived with either a biological father only, extended family, or in foster or temporary care. Based on administration of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview for Children (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000), the most common type of mental health diagnosis in this sample was a disruptive behavior disorder (56%), supporting our focus on delinquent behavior. Other common diagnoses included depressive disorders (32%), anxiety disorders (24%), and post traumatic stress disorder (16%). The most common length of stay for adolescents in the final sample was 5 to 7 days.

2.2 Measures

The current study utilizes measures of adolescent substance use, delinquent behavior, and depression. These measures were administered at baseline, 9 months, and 18 months.

Health Risk Behaviors (HRB) Questionnaire

Frequency of substance use was assessed via the HRB Questionnaire. The HRB is a self-report measure based on the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YBRSS; Kann et al., 2000). To address our study hypotheses, we examined two items assessing alcohol use frequency (days of any alcohol use and days of 5+ drinks) and one item assessing marijuana use frequency (days of any marijuana use). Each item accounted for the adolescent’s lifetime history of use and level of use over the past 30 days. Responses were scored on Likert scales, with options ranging from “0 = never used” to “5 = used 10 or more of the past 30 days.” In the 1999 YBRS survey, the items used in this study demonstrated substantial test-retest reliability (kappa values = .68 –.76) in a sample of 4,619 adolescents across 20 states (Brener et al., 2002).

Delinquency Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ)

The DBQ is a 12-item self-report measure of externalizing symptoms that was adapted from the Self-Reported Delinquency Interview (Elliott, 1985). Items in the DBQ assessed the frequency of adolescents’ participation in illegal and delinquent behaviors commonly included in measures of externalizing symptomatology such as engaging in a physical fight, damaging property, setting fires, carrying a weapon, skipping class, and cheating on a test. Adolescents rated how often they had done each behavior over the past year on a 5-point Likert scale. An overall score was calculated as the sum of the individual items, with higher scores indicating more delinquent behavior. In an analysis of the full study sample (Prinstein, et al., 2008), the mean score across items demonstrated significant correlations with conduct disorder symptoms reported on the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version IV (Shaffer, et al., 2000) by both adolescents (r =.78, p < .001) and their parents (r = .29, p < .01). Internal consistency in this sample was .88.

2.3 Missing Data

Of the 108 adolescents who completed the baseline substance use measures, 83 (77%) completed the 9 month assessment and 81 (75%) completed the 18 month assessment. Seventy eight adolescents (72%) completed both assessments. Comparisons between those adolescents with and without missing data did not reveal any significant differences between the groups on age, gender, days of alcohol use, days of marijuana use, or delinquent behavior, providing no indication of attrition bias. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation, a method that has been shown to generate unbiased parameter estimates when data are missing at random (Enders, 2001), was used to handle missing data. Although FIML is robust to data missing at random, there is mixed support for its robustness with non-normality. All analyses were therefore conducted using the Yuan and Bentler (2000) correction for multivariate non-normality.

2.4 Analysis Plan

Prior to testing the study hypotheses, baseline correlations among the study variables were calculated. In addition, we tested for differences among the predictors as a function of standard demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, ethnicity). These analyses were conducted to determine whether demographic variables were significantly associated with the dependent variables and needed to be retained in the model. The two alcohol use measures, days of any alcohol use and days of high-volume drinking (e.g., 5+ drinks per day), demonstrated a very large, significant correlation (r = .93, p < .001), suggesting that examining both variables would provide redundant information. We therefore focused on days of alcohol use to be consistent with days of marijuana use, and conducted analyses on days on high volume drinking to test the robustness of our findings.

To test the study hypotheses, cross lagged panel models were estimated. Cross-lagged panel modeling is frequently utilized to assess the causal direction between variables in data derived from non-experimental, longitudinal research designs (Finkel, 1995). Two sets of models were constructed: one with days of alcohol use as a dependent variable and a second with days of marijuana use as a dependent variable. All analyses were conducted in MPlus version 6.0 (Muthen & Muthen, 2010).

We began by estimating a baseline model that freely estimated all paths between delinquent behavior and days of use. Next, we estimated increasingly constrained models to obtain the most parsimonious model fit. Constraints were systematically added to the baseline model to reflect the assumption that similar effects should be stable over time. We first added constraints on the stability effects for each variable (e.g. the stability of delinquent behavior from baseline to 9 months was set equal to the stability from 9 to 18 months), then on the within time-point residual correlations (e.g. the residual correlation of delinquent behavior and days of use at 9 months was set equal to the residual correlation at 18 months), and finally on the cross-lagged effects (e.g. the cross-lagged effect of delinquent behavior on days of use from baseline to 9 months was set equal to the cross-lagged effect from 9 to 18 months). Using the chi-square difference test, we compared the baseline model to the constrained models. Because there were two time intervals, each model comparison involved a one degree of freedom change.

Fit of each cross-lagged panel model was evaluated using three conventional indexes: chi-square, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and comparative fit index (CFI). Chi-square analysis tests the hypothesis that the specified model fits the observed covariances, with p values greater than .05 indicating acceptable fit. Relative to chi-square, RMSEA and CFI are indices that are less influenced by model parameters such as sample size and number of variables. Consistent with conventional criteria (Hu, 1999), RMSEA values under .08 and CFI values over .9 were viewed as indicating acceptable fit to the data.

3. Results

3.1 Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, and item distributions of the substance use and delinquency variables, across all three time points. At each assessment, the mean scores for frequency of alcohol and marijuana use reflect relatively infrequent use. However, the item distributions indicate that a substantial proportion of these early adolescents had used illicit substances. At baseline, 49% of the sample reported a lifetime history of alcohol use and 43% reported a lifetime history of marijuana use. The proportion of youth reporting a lifetime history of alcohol use steadily increased 14% over the two follow-up assessments. By contrast, the proportion of youth reporting a lifetime history of marijuana use remained stable between baseline and 9 months, and then increased 15% between the 9 and 18 month assessment.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the substance use variables and delinquent behavior at each wave for psychiatrically hospitalized early adolescents

| Variable, M (SD) or N (%) | Baseline N = 108 |

Study wave 9 months N = 83 |

18 months N = 81 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol frequency | 1.04 (1.39) | 1.08 (1.39) | 1.30 (1.40) |

| Never used | 55 (51%) | 36 (43%) | 30 (37%) |

| Lifetime use, 0 of past 30 days | 23 (21%) | 27 (32%) | 24 (29%) |

| Lifetime use, 1–2 of past 30 days | 15 (14%) | 9 (11%) | 12 (15%) |

| Lifetime use, 3–5 of past 30 days | 5 (5%) | 4 (5%) | 8 (10%) |

| Lifetime use, 6–10 of past 30 days | 6 (6%) | 2 (2%) | 5 (6%) |

| Lifetime use, 10+ of past 30 days | 4 (4%) | 5 (6%) | 3 (4%) |

| Marijuana frequency | .87 (1.33) | .80 (1.25) | 1.11 (1.44) |

| Never used | 61 (57%) | 48 (59%)a | 36 (44%) |

| Lifetime use, 0 of past 30 days | 25 (23%) | 18 (22%) | 27 (33%) |

| Lifetime use, 1–2 of past 30 days | 10 (9%) | 4 (5%) | 3 (4%) |

| Lifetime use, 3–5 of past 30 days | 3 (3%) | 6 (7%) | 7 (9%) |

| Lifetime use, 6–10 of past 30 days | 5 (5%) | 4 (5%) | 4 (5%) |

| Lifetime use, 10+ of past 30 days | 4 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (5%) |

| Delinquent behavior questionnaire | 21.08 (9.09) | 18.16 (8.72) | 16.95 (5.40) |

Due to varying Ns at the different follow-up periods, the percent of adolescents reporting “never used” increased slightly from baseline to 9 months

Baseline associations among the study variables are depicted in Table 2. Days of any alcohol use and days of marijuana use were moderately correlated (r = .65, p < .01), and both were correlated with delinquent behavior (alcohol use, r = .52, p < .01; marijuana use, r = .53, p < .01). None of the study variables were significantly correlated with age. Using paired t-tests, there were no gender or ethnic differences in frequency of alcohol use, frequency of marijuana use, or delinquent behavior at baseline. Since gender, age, and ethnicity were not associated with any of the dependent variables, these demographic variables were not retained in the final models. Replication of the models controlling for these demographic variables revealed an identical pattern of results with regard to statistical significance and effect sizes; however, the inclusion of these variables resulted in less favorable fit indices, supporting their exclusion from the final model.

Table 2.

Baseline correlations among the substance use variables, delinquent behavior and age for psychiatrically hospitalized early adolescents

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Frequency of alcohol use | ||||

| 2. | Frequency of marijuana use | .65* | |||

| 3. | Delinquent behavior (DBQ) | .52* | .53* | ||

| 4. | Age | .16 | .12 | .02 |

Note. DBQ = Delinquent behavior questionnaire.

p < .01

3.2 Temporal Effects of Substance Use and Delinquent Behavior

To test the study hypotheses, two cross-lagged panel models were estimated to assess the reciprocal relationship between delinquent behavior and frequency of alcohol and marijuana use, respectively, across three waves of data. Results of the two models are reported below.

Frequency of alcohol use

The baseline model that freely estimated the stability effects, within time-point correlations, and cross-lagged effects for days of alcohol use and delinquent behavior demonstrated excellent fit to the data, χ2(4) = 4.44, p = .35, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .03. Model comparisons with the chi-square difference test indicated that adding constraints on the stability and cross-lagged effects did not significantly affect model fit. However, adding constraints on the within-time point correlations significantly reduced the fit of the model, Δχ2(1) = 11.33, p < .001, suggesting that the associations between deviant behavior and days of alcohol use were not stable over time. Thus, the final, most parsimonious model was estimated with this equality constraint released: χ2 (8) = 8.59, p = .38, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .03.

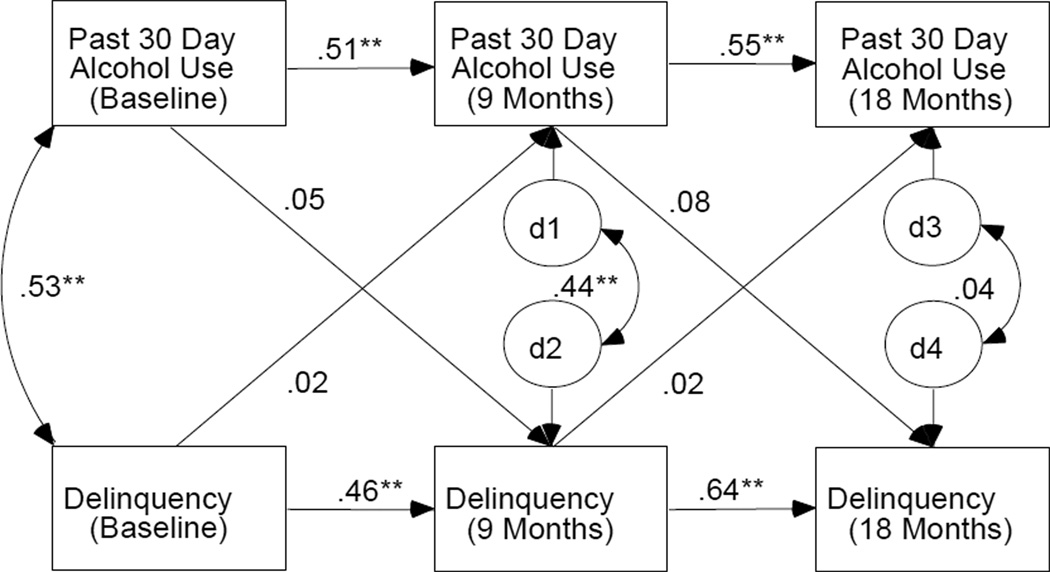

As shown in Figure 1, significant and moderately large stability effects were found for both days of alcohol use and delinquent behavior following hospitalization. In addition, the association between days of alcohol use and delinquent behavior was significant at 9 months, but not at 18 months. At baseline, the association between days of alcohol use and delinquency is simply a correlation. At later time points, the association is a residual correlation, which is the partial correlation of the measures when controlling for earlier time points. The lack of a significant correlation at 18 months indicates that any shared variance between days of alcohol use and delinquent behavior was accounted for by the prior two time points. Despite evidence of significant associations, and counter to our hypothesis, no predictive effects were found between days of alcohol use and delinquent behavior across adjacent waves of data. An identical pattern of significant stability effects and non-significant cross lagged effects was found when replicating these analyses using days of high volume drinking rather than days of alcohol use.

Figure 1.

Cross-lagged panel model for the temporal relationship between frequency of alcohol use and delinquent behavior. Parameter estimates are standardized values. * p < .01, ** p < .001

Days of marijuana use

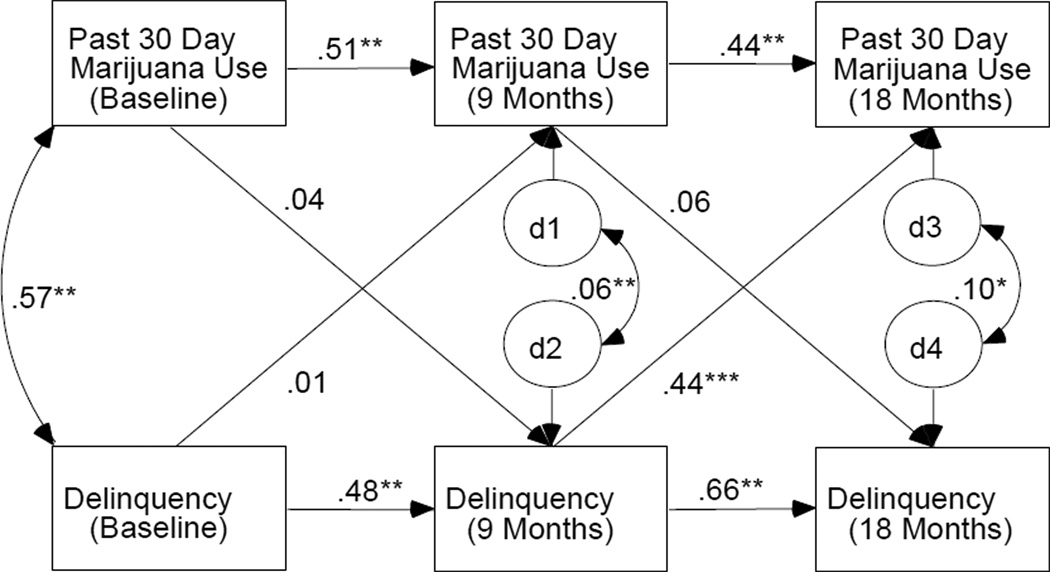

The baseline model that freely estimated the stability and cross-lagged effects for days of marijuana use and delinquent behavior demonstrated excellent fit to the data, χ2(4) = 5.47, p = .24, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .06. Model fit was not affected by adding equality constraints on the stability effects, the within time-point associations, or the cross-lagged effects from days of marijuana use to delinquent behavior. However, adding equality constraints on the cross-lagged effects from delinquent behavior to days of marijuana use had a significant, negative effect on model fit, Δχ2(1) = 7.60, p < .01. This suggests that the effect of delinquent behavior on subsequent marijuana use was not stable over the 18 month follow up period. The final model was estimated with this constraint released and demonstrated the most parsimonious fit: χ2(8) = 12.15, p = .14, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .07.

As shown in Figure 2, significant and moderately large stability effects were found for both days of marijuana use and delinquent behavior. Residual correlations between days of marijuana use and delinquent behavior were significant at both follow-up points, indicating that there was considerable unique variance between the variables at each time point that was not accounted for by earlier occasions. In partial support of our hypothesis, delinquent behavior at 9 months had a significant cross lagged-effect on days of marijuana use at 18 months. Days of marijuana use did not have cross-lagged effects on delinquent behavior. Hence, the model suggests that in this sample of hospitalized youth, delinquent behavior at 9 months predicted subsequent marijuana use, but marijuana use did not predict subsequent delinquent behavior.

Figure 2.

Cross-lagged panel model for the temporal relationship between frequency of marijuana use and delinquent behavior. Parameter estimates are standardized values. * p < .01, ** p < .001.

4. Discussion

The current study examined the longitudinal relationship between delinquent behavior and frequency of use for the two most common illicit substances – alcohol and marijuana – among adolescents following psychiatric hospitalization. Rates of alcohol and marijuana use in this sample of early adolescents are significantly higher than those reported in national community samples of youth (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2010; Substance Abuse and Mental Helath Services Administration, 2010). For example, the 2010 Monitoring the Future Study’s survey of 8th graders found that 35.8% and 17.3% reported a lifetime history of alcohol and marijuana use, respectively (Johnston, et al., 2010), versus reported rates of 49% and 43% in the current sample. Furthermore, the 2009 National Survey of Drug Use & Health found that 14.7% and 7.3% of 12 to 17 year olds reported any past month use of alcohol and marijuana use, respectively, relative to rates of 28% and 20% in the current sample. These high lifetime and past month rates of alcohol and marijuana use (see Table 1) are consistent with the rates of substance use reported in other psychiatric samples of adolescents (Deas-Nesmith, Campbell, & Brady, 1998; Martin, Milich, Martin, Hartung, & Haigler, 1997). It is also noteworthy that there were substantial increases in substance use rates over the 18 month follow-up period, despite the fact that the majority of this sample received mental health treatment (M = 8.1 sessions, SD = 4.7 sessions) following discharge from the hospital (Spirito et al., 2011).

Results of the current analysis provided partial support for our primary hypothesis for marijuana use frequency, but not for alcohol use frequency. The cross-lagged panel model for frequency of marijuana use found that delinquent behavior at 9 months predicted subsequent marijuana use, while marijuana use did not predict subsequent delinquent behavior. These results were consistent with prior research demonstrating a unidirectional predictive relationship between delinquency and later substance use (Bui, et al., 2000; Mason, et al., 2007) as well as other studies which failed to demonstrate a robust reciprocal relationship (Dembo, et al., 2002; Mason & Windle, 2002). In contrast to prior studies we found that the effects of delinquent behavior on subsequent marijuana use were not stable over time. In the current sample, the effect of delinquent behavior on marijuana use was small and insignificant in the first 9 months following hospitalization, and became moderate and significant over the next 9 months. This inconsistency may reflect the relatively young age of our sample, as well as variability in the initiation of marijuana use over time. Based on adolescent self-report, lifetime history of marijuana use increased more substantially between the 9 and 18 month follow up (increase of 15%), when the mean age of the sample was approaching 15, than between the baseline and 9 month follow-up. Variability in marijuana initiation rates has also been found in large national samples, which have shown a steady increase in incidence rates between the ages of 13 and 17 years (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010). Although it would be remiss to infer developmental relationships from a small sample, our pattern of results supports the notion that both the initiation of marijuana use, and the relationship between delinquent behavior and marijuana use, may vary across the developmental period.

Counter to our expectations and prior research (Huang, White, Kosterman, Catalano, & Hawkins, 2001; Mason, et al., 2007), no predictive effects were found between alcohol use and delinquent behavior over time. Consistent with prior studies (Kosterman, et al., 2000), lifetime rates of alcohol use were higher than lifetime rates of marijuana use in this sample, suggesting that alcohol use may be more normative and less influenced by delinquent peers among early adolescents. It is also important to consider that the correlations between alcohol and delinquent behavior were not stable over time. Despite evidence of significant and moderate associations at baseline and 9 months, the within time-point association was small and insignificant at the 18 month follow up. An identical pattern was found when examining the days of high volume drinking variable. These data suggest that by the 18 month assessment, shared variance between days of alcohol use and delinquent behavior was fully accounted for by earlier occasions. The lack of an association by 18 months may reflect the stability of these externalizing behaviors in this sample of early adolescents. Further research with larger samples and more frequent assessment intervals is needed to confirm these findings.

Study findings must be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, the study relied on self-report data to measure delinquent behavior, which is often assessed using parent report and may have led to the underestimation of this behavior. Substance use was also measured via self-report and not corroborated. Second, the small sample size may have limited power to detect significant effects. The fact that we found a significant, modest effect of deviant behavior at 9 months on subsequent marijuana use attests to the strength of the association. However, the small sample size increases the likelihood that the parameter estimates might be unstable. Third, the analysis focused on frequency of alcohol and marijuana use, and did not consider severity of use or other types of substance use. Of note, the same pattern of results was found when examining days of alcohol use and days of high volume use, suggesting that the observed results are likely robust to measures of heavier substance use. Finally, it is possible that unmeasured variables might account for the relationship between delinquent behavior and substance use. For instance, Mason and colleagues (2007) found that the relationship between alcohol use and delinquency was partially mediated by peer substance use.

It is somewhat premature to derive intervention implications from the current study due to the naturalistic, non-experimental design. Nevertheless, the present findings lend preliminary support for utilizing interventions targeting delinquency among young adolescents with significant mental health concerns as a means of not only addressing problem behavior, but also potentially preventing the onset of later marijuana use. The current study also supports educating parents of early adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems about the consistently high rates of substance use and substance initiation as they transition from middle school to high school, which approximates the age range of this sample. Future research is needed to test potential mediators underlying the relationship between delinquency and substance use among early adolescents with significant psychopathology in order to determine the best approach for intervention with this vulnerable population. Potential mediators may include those related to parenting (e.g., monitoring, communication, involvement), peer relationships (e.g., deviant peer affiliations), or other domains. Moreover, the differential pattern of effects for marijuana and alcohol highlight the need for future studies to examine these substances separately to better understand the complex pathways between delinquency and use among adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH59766) and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention awarded to Mitchell J. Prinstein.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

A portion of this manuscript was presented at the 41st Annual Meeting of the European Association for Cognitive and Behavioural Therapy in August of 2011.

Contributor Information

Sara J. Becker, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Jessica E. Nargiso, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Jennifer C. Wolff, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Kristen M. Uhl, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Valerie A. Simon, Wayne State University

Anthony Spirito, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Mitchell J. Prinstein, University of North Carolina

References

- Anthony JC, Petronis KR. Early-onset drug use and risk of later drug problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;40:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(6):1224–1239. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, Kinchen SA, Sundberg EC, Ross JG. Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(4):336–342. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui KVT, Ellickson PL, Bell RM. Cross-Lagged Relationships Among Adolescent Problem Drug Use, Delinquent Behavior, and Emotional Distress. Journal of Drug Issues. 2000;30(2):283–303. [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Edelen MO, Miles JN, Morral AR. The longitudinal association between substance use and delinquency among high-risk youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;9385(1–2) doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deas-Nesmith D, Campbell S, Brady KT. Substance use disorders in an adolescent inpatient psychiatric population. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1998;90(4):233–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Wothke W, Seeberger W, Shemwell M, Pacheco K, Rollie M, et al. Testing a longitudinal model of the relationships among high risk youths' drug sales, drug use and participation in index crimes. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2002;11(3):37–61. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty EE, Green KM, Ensminger ME. Investigating the long-term influence of adolescent delinquency on drug use initiation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93(1–2):72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining Delinquency and Drug Use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. The Performance of the Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimator in Multiple Regression Models with Missing Data. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61(5):713–740. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel SE. Causal Analysis with Panel Data. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: Early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16(1):193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JA. Substance Use, the Social Bond, and Delinquency. Sociological Inquiry. 2005;75(1):109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Franken IHA, Hendriks VM. Early-onset of illicit substance use is associated with greater axis-II comorbidity, not with axis-I comorbidity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59:305–308. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French DC, Dishion TJ. Predictors of Early Initiation of Sexual Intercourse among High-Risk Adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2003;23:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein A, Herrera J. Heroin addicts and methadone treatment in Albuquerque: a 22-year follow-up. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;40(2):139–150. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayatbakhsh MR, Najman JM, Jamrozik K, Al Mamun A, Bor W, Alati R. Adolescent problem behaviours predicting DSM-IV diagnoses of multiple substance use disorder. Findings of a prospective birth cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(5):356–363. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Thornberry TP, Huizinga DH. A discrete-time survival analysis of the relationship between truancy and the onset of marijuana use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(1):5–15. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.5. PMCID: 2629625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, White HR, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. Developmental associations between alcohol and interpersonal aggression during adolescence. Journal of Research on Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38:64–83. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2010. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams BI, Ross JG, Lowry R, Grunbaum JA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 1999. Journal of School Health. 2000;70(7):271–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99(12):1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Guo J, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. The dynamics of alcohol and marijuana initiation: Patterns and predictors of first use in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:360–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP. Young children who commit crime: Epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12(4):737–762. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG, Malone SM. Longitudinal associations between depression and substance dependence from adolescence through early adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107(2–3):154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.002. PMCID: 2822052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CA, Milich R, Martin WR, Hartung CM, Haigler ED. Gender differences in adolescent psychiatric outpatient substance use: Associated behaviors and feelings. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(4):486–494. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Ellickson PL, McCaffrey DE. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early to late adolescence: A comparison of rural and urban youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(3):430–440. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Hitchings JE, Spoth RL. Emergence of delinquency and depressed mood throughout adolescence as predictors of late adolescent problem substance use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21(1):13–24. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Windle M. Reciprocal relations between adolescent substance use and delinquency: a longitudinal latent variable analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(1):63–76. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus (Version 6) Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parker RN, Auerhahn K. Alcohol, Drugs, and Violence. Annual Review of Sociology. 1998;24:291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Nock MK, Simon V, Aikins JW, Cheah CS, Spirito A. Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts following inpatient hospitalization. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(1):92–103. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Simon V, Cancilliere MK, Stein R, Norcott C, Loranger K, et al. Outpatient psychotherapy practice with adolescents following psychiatric hospitalization for suicide ideation on a suicide attempt. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;16:53–64. doi: 10.1177/1359104509352893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, Cauffman E. Juvenile justice, delinquency, and psychiatry. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1998;7(3):653–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume I. Summary of National Findings. (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4856 Findings) Rockville, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Helath Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Elkington KS, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Mericle AA, Washburn JJ. Major mental disorders, substance use disorders, comorbidity, and HIV-AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):823–828. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.7.823. PMCID: 1557408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bree MB, Pickworth WB. Risk factors predicting changes in marijuana involvement in teenagers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(3):311–319. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner B, Vitaro F, Carbonneau R, Tremblay RE. Cross-lagged links among gambling, substance use, and delinquency from midadolescence to young adulthood: additive and moderating effects of common risk factors. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(1):91–104. doi: 10.1037/a0013182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]