Abstract

Objective

There is wide variation in therapeutic approaches to systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) among North American rheumatologists. Understanding the comparative effectiveness of the diverse therapeutic options available for treatment of sJIA can result in better health outcomes. The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) developed consensus treatment plans and standardized assessment schedules for use in clinical practice to facilitate such studies.

Methods

Case-based surveys were administered to CARRA members to identify prevailing treatments for new-onset sJIA. A 2-day consensus conference in April 2010 employed modified nominal group technique to formulate preliminary treatment plans and determine important data elements for collection. Follow-up surveys were employed to refine the plans and assess clinical acceptability.

Results

The initial case-based survey identified significant variability among current treatment approaches for new onset sJIA, underscoring the utility of standardized plans to evaluate comparative effectiveness. We developed four consensus treatment plans for the first 9 months of therapy, as well as case definitions and clinical and laboratory monitoring schedules. The four treatment regimens included glucocorticoids only, or therapy with methotrexate, anakinra or tocilizumab, with or without glucocorticoids. This approach was approved by >78% of CARRA membership.

Conclusion

Four standardized treatment plans were developed for new-onset sJIA. Coupled with data collection at defined intervals, use of these treatment plans will create the opportunity to evaluate comparative effectiveness in an observational setting to optimize initial management of sJIA.

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) is a rare and complex inflammatory disease of childhood associated with significant morbidity. SJIA is characterized by arthritis accompanied by high spiking fevers plus a variety of additional features such as a typical rash, generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and serositis. There is considerable variation in the therapeutic approaches to new onset sJIA, in part due to a heterogeneous and somewhat unpredictable disease course, differences in physician practices, and until recently, a lack of clinical trial data(1–3) and evidence based guidelines(4) targeting this population.

SJIA accounts for 5–15% of patients diagnosed with some form of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) in North American and European populations. It accounts for a disproportionate share of the morbidity in childhood arthritis, including poor growth, severe joint destruction causing physical disability and necessitating joint replacement surgery (5), and JIA related deaths (6). The disease course is variable, with approximately 11% to 42% of patients following a monocyclic course of variable length. The majority of affected children have a chronic and unrelenting course, while a smaller fraction (7%–34%) follow a polycyclic course punctuated by flares and remission of arthritis, with or without systemic features(6–9). Deaths occur more frequently in children with sJIA than other categories, mostly due to overwhelming infection (historically associated with chronic glucocorticoid treatment), macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) and amyloidosis (mainly outside North America)(6,10,11). Correlates of poor prognosis include continued active systemic disease 6 months after diagnosis (as manifested by fever, requirement for systemic glucocorticoids, or thrombocytosis)(10), aggressive polyarthritis (12) and cervical spine involvement(13).

Systemic glucocorticoids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been the mainstays of treatment for many years, but glucocorticoids, which must often be given for years in this disease, are associated with many side effects(14). For treatment of the articular disease, methotrexate and sometimes tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors (such as etanercept and infliximab) have been used with limited success (15, 16). However, these treatments have in some settings been supplanted by the use of an anti-interleukin 1 (IL1) therapy, anakinra, which has been reported to result in dramatic improvement in both the systemic and articular disease in some patients with sJIA (9, 17). Anakinra has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of adult rheumatoid arthritis, but its use for sJIA is currently “off-label.” An anti-interleukin 6 (IL6) therapy (tocilizumab) recently became the first treatment approved by the FDA for sJIA (April 15, 2011), and has also been demonstrated to be of remarkable benefit (3). Additional anti-IL1 therapies (such as canakinumab and rilonacept) are currently in clinical trials in sJIA.

With these new options for treatment, there is an urgent need for research to determine their relative effectiveness, safety and tolerability in sJIA. Comparative effectiveness studies in an observational setting may be used to examine which treatments are effective in routine care and help guide decision-making about which treatment may be most appropriate for an individual patient(18). SJIA, being a relatively uncommon, severe disease with widely diverging therapeutic approaches, is particularly suited for comparative effectiveness research. To be able to carry out meaningful comparisons between therapeutic agents in an observational setting, however, requires standardization of treatment regimens and outcome measures. In this present effort, we therefore aimed to develop consensus derived standardized treatment plans for this disease as part of improving patient outcomes in sJIA, a scientific priority of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA). CARRA is a North American organization whose research mission is to prevent, treat and cure rheumatic diseases in children through fostering and conducting high quality research. Our aim was to generate treatment plans and data collection recommendations similar to current clinical practice. This would increase the likelihood of their use by practicing pediatric rheumatologists and lead to standardization of care for many sJIA patients, in order to reduce unwarranted variation in care and increase the ability to make meaningful comparisons of the relative effectiveness of treatments. In addition, these treatment plans may guide practicing clinicians and serve as a discussion tool for patients and families. Although these plans may differ from the usual practice of some physicians, the intent was to develop plans that most physicians would feel comfortable using despite modest differences from their usual practice. In addition, use of these plans is not meant to replicate a clinical trial protocol: they are not meant to be proscriptive; physicians should use a consensus treatment plan (CTP) when that physician feels it is appropriate to use in a given patient; and the treating physician may diverge from any CTP if it is felt that it is in the patient’s best interest to do so.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The CARRA sJIA core workgroup (YK, EMD, RS, PN, TB, MS, SP, KO), consisting of board certified pediatric rheumatologists with special interest and expertise in sJIA, met once or twice monthly from October 2009 to March 2011 to review published evidence, formulate clinical scenarios and an operational case definition describing characteristics of patients intended for the treatment plans, construct surveys, analyze responses, organize and run a consensus meeting, and finalize resultant treatment plans.

Pre-consensus meeting survey

A case-based on-line survey was administered to CARRA members in the JIA disease specific workgroup to identify prevailing therapeutic approaches to treatment of new onset sJIA according to four clinical scenarios that represented varying severity of disease activity (mild, moderate, moderate-high, and high). Survey respondents reported first-line, second-line and also third-line treatment choices for patients with inadequate response to the prior regimen. Discrete options as well as free text items were included. Respondents also provided input on formulation of characteristics of the patients to be treated, such as the minimum duration of fever before a diagnosis of sJIA would be considered probable. Responses were analyzed and served as the basis for a 2-day consensus conference which convened in April 2010 during the CARRA Annual Scientific Meeting. A sample of questions and response options is presented as Appendix 1.

Consensus meeting

Pediatric rheumatologists, fellows-in-training, researchers, and lay members (who were parents of children with JIA) attended the sJIA consensus treatment plan meeting along with three facilitators (YK, EMD, Edward Giannini). The setting was the CARRA annual scientific meeting. Voting participants were CARRA members in clinical practice who treat patients with JIA and were members of the CARRA JIA disease specific committee. Clinician participation was valued for their experience and as stakeholders in the process, as clinicians will be the ones to use the consensus treatment plans. After a presentation of the overall meeting goals and objectives, pre-conference survey data, and an overview of consensus methodology, participants divided into 3 self-selected workgroups to determine the details of 1) a glucocorticoid treatment plan, 2) a disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment plan, and 3) assessment details. Within each workgroup, extensive input was sought from all meeting attendees through structured small group interactions. Specific questions were posed for discussion, and an 80% level of agreement for each question was required to consider consensus to have been achieved. After completion of each group’s panel of questions, workgroup participants reconvened as a larger group for presentation of the progress of each work group. Topics were then presented for discussion with the larger group to obtain more widespread consensus. Where there was not clear agreement of the larger group by a show of hands, after additional discussion, a more formal voting process occurred. After the meeting, questions for which consensus answers were not achieved were brought back to the CARRA sJIA core workgroup for further analysis, discussion and decision-making. Additionally, the preliminary treatment plans created at the meeting were further refined by this core workgroup. A subsequent presentation of the revised treatment plans was then presented to the entire CARRA membership for review and response by an on-line survey.

Post-consensus meeting survey

The on-line survey of the entire CARRA membership described above was conducted in December 2010 to assess the acceptability and feasibility of use of the revised treatment plans derived from the 2010 consensus meeting. The thematic content of the questions included: 1) a review for acceptability of the proposed operational case definition for sJIA, 2) specification of the details of the three treatment plans developed during the consensus meeting (glucocorticoid plan, methotrexate plan, anti-IL1 -anakinra - plan), 3) whether an anti-IL6 treatment plan should be added, 4) willingness to use one of the presented plans on newly diagnosed sJIA patients, and 5) estimation of the number of patients that might be treated with each plan yearly. A sample of survey questions are presented as Appendix 2.

Based on these survey results, the CARRA sJIA core workgroup further refined the treatment plans and monitoring schedules presented herein.

RESULTS

The pre-consensus meeting case-based survey was completed by 63 of 137 members of the CARRA JIA disease specific workgroup (46% response rate, an expected rate based on completion rates of other CARRA membership surveys and given the complexity of the survey). The survey identified considerable variability in current therapeutic approaches to new onset sJIA, confirming the suitability of sJIA as a target for comparative effectiveness research. As an example, the initial treatment choices among the respondents for the sJIA patients described in the cases included anti-IL1, anti-IL6 and anti-TNF agents, calcineurin inhibitors, methotrexate (oral and injectable), IV methylprednisolone pulse(s), NSAIDs and prednisone (low, mid or high-dose), depending on the severity of the patient. Several distinct treatment preferences emerged. In summary, NSAIDs were used widely across the disease severity spectrum as part of initial treatment, trending down as disease activity increased (85.7% for mild cases, down to 39.7% for high disease activity). Use of methotrexate (37.9–43.3%) was stable across the disease activity spectrum. As disease activity increased, so did use of methylprednisolone pulses and anti-IL1. Failure to respond to the above resulted in use of anti-IL6, and to a lesser extent, calcineurin inhibitors and anti-TNF (see Appendix 3). The operational case definition for new onset sJIA which a patient should meet prior to initiating any of the standard treatment plans was also addressed. 74.1% of respondents thought that a minimum of 2 week duration of fever should be required. The majority (87.9%) found it acceptable to initiate a treatment for sJIA in the absence of arthritis, based on fever and other systemic features such as characteristic rash, serositis, and adenopathy, provided that infection and malignancy had been adequately excluded.

Forty-three CARRA members attended the face-to-face consensus meeting in April 2010, as did 2 non-voting lay parent members and 3 facilitators. The glucocorticoid treatment plan group generated a draft treatment approach that offered a choice of either high dose (2mg/kg/daily) or low dose (0.5mg/kg/daily) oral prednisone, with methylprednisolone pulses and/or intra-articular injections as needed. The goal was to discontinue glucocorticoids by 6 months, with defined tapering schedules to proceed as tolerated. The DMARD treatment plan group generated draft methotrexate- and anakinra-based plans, each of which could be used with the glucocorticoid plan if needed. The assessment details group developed schedules of proposed visit intervals, laboratory and clinical assessments and data collection items(19).

After refinement of the operational case definition and treatment plans by the sJIA core workgroup, a survey of the entire CARRA membership was conducted in December 2010 to assess their acceptability and feasibility. Most respondents found the proposed adjustments made by the sJIA core workgroup, specifically the glucocorticoid plan and patient characteristics to be included in the operational case definition (now requiring at least one joint with arthritis observed by a physician to be present), to be acceptable (Table 1). There was a 63% response rate (133 of 211 surveyed), of which 92.6% expressed willingness to follow glucocorticoid, methotrexate or anti-IL1 treatment plans as outlined. 82% concurred that an anti-IL6 based treatment plan should also be offered. Consensus was reached at the 78–85% level for all topics posed (acceptability of patient characteristics, specific details of presented treatment plans, ability to use plans). Respondents were also asked to rank the four CTPs in terms of likelihood of use, with 1 being most likely and 4 being least likely, and there was a relatively even distribution of ratings among the CTPs: glucocorticoids (mean rating 2.48); methotrexate (2.05); anakinra (2.0); and tocilizumab (3.26—note that tocilizumab had not yet received FDA approval for sJIA at the time of the survey). The survey may be found in Appendix 2.

Table 1.

Operational case definition of new onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis used in development of treatment plans

| Patient should have: |

Patient should not have any of the following:

|

Daily fever is not required, but must at some point exhibit a quotidian fever pattern, defined as fever that rises to ≥39°C at least once a day and returns to ≤37°C between fever peaks.

Swelling within a joint, or limitation in the range of joint movement with joint pain or tenderness, is observed by a physician, and which is not due to primarily mechanical disorders or to other identifiable causes.

Infections, malignancy and other diagnoses which can present with similar symptoms as sJIA should be excluded before initiating treatment plans for new onset sJIA in order to avoid unintended adverse effects of the treatment plans if used for other diagnoses.

Prior treatment with steroids should not exceed 2 weeks of oral steroids, and/or 3 pulses of methylprednisolone. Prior treatment with IVIG for possible Kawasaki Disease is allowed. Duration of NSAIDs is without restriction.

- ILAR specifies that the duration of quotidian fever has to be 3 days (the total duration of fever is two weeks in both)

- ILAR specifies six weeks’ duration of arthritis

- Psoriasis, positive RF, arthritis in HLA B27 positive male after 6 years of age, family history of AS, IBD with sacroiliitis, acute anterior uveitis and reactive arthritis are listed as exclusions in the ILAR definition

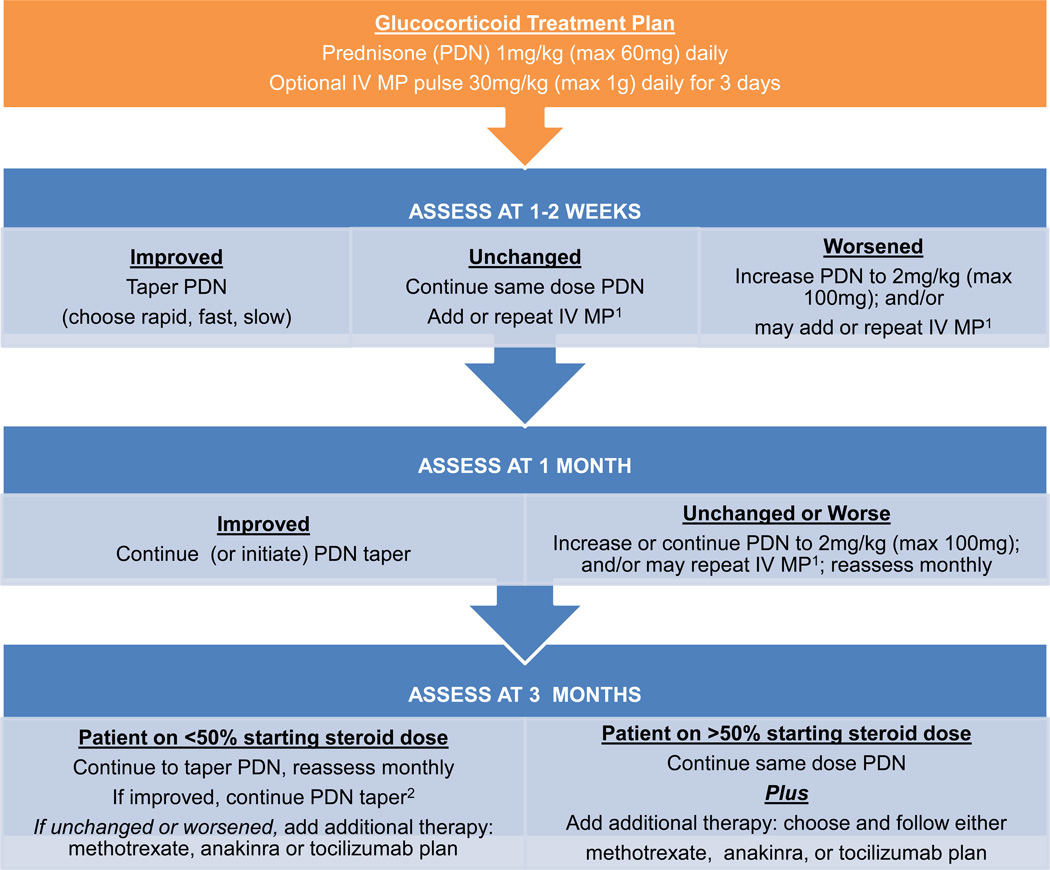

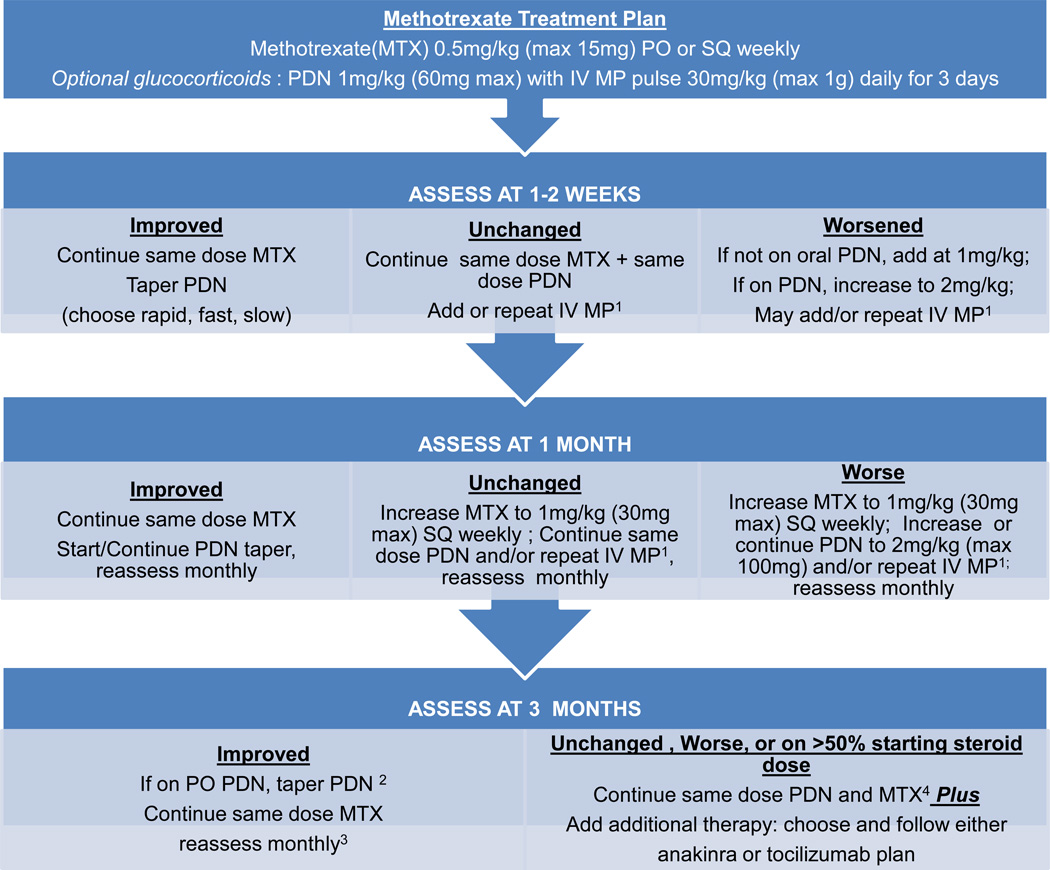

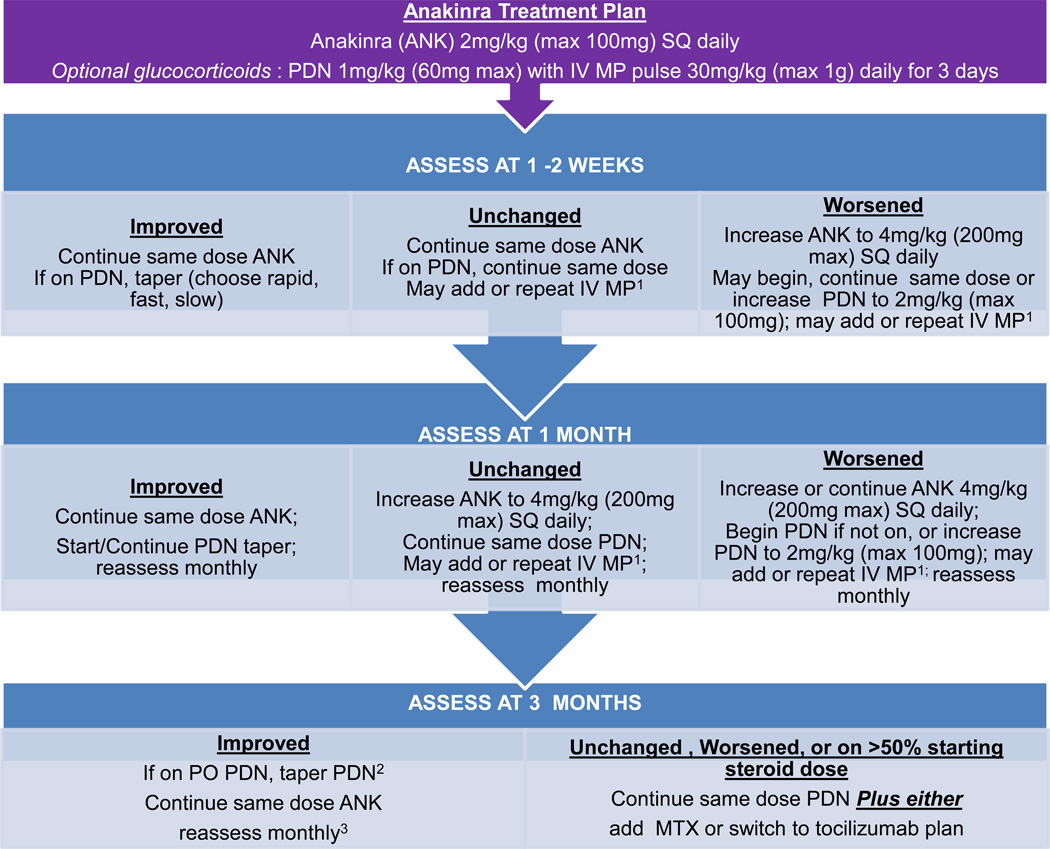

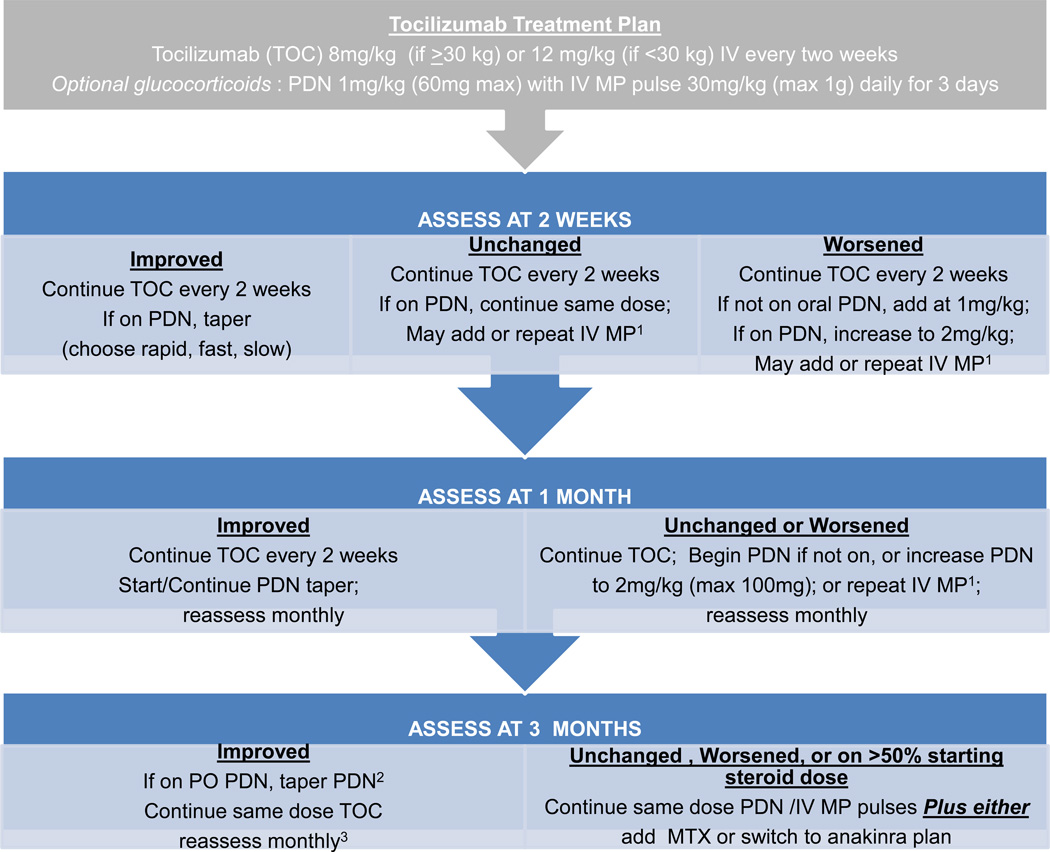

These standardized treatment plans evolved iteratively through meetings of the sJIA core workgroup to the final treatment plans presented as Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4, which include the addition of a fourth plan (anti-IL6 [tocilizumab]). Appendix 4 presents the plans in written form. The glucocorticoid only plan was simplified, without provision for maintenance IV methylprednisolone pulses, and glucocorticoid tapering guidelines were developed (rapid, fast, slow) with a stated target to be at 50% the initial dose by 3 months and discontinue by 6 months or earlier (Appendix 5). The methotrexate and two biologic DMARD plans allow for addition of glucocorticoids with dosing according to the glucocorticoid only plan. NSAIDs may be added to any treatment plan. All plans follow a routine assessment schedule (Table 2), and suggest switching treatment plans in any of the following circumstances: 1) inadequate response, 2) inability to wean glucocorticoids by at least 50% the starting dose by 3 months, or 3) disease worsening in the first 3 months. Suggested assessment intervals correspond with decision points in the treatment plans. Duration of treatment plans covers the initial 9 months of treatment in order to capture at least 6 months of treatment with a second line agent if a treatment switch is made at 3 months. As the decision to continue with a treatment, add or increase glucocorticoids, or change to a different treatment is dependent on physician judgment, components of evaluation and determination of disease status (worsened, unchanged, improved) were also included. These components include joint count, systemic features, and suggested minimum laboratory evaluations (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Glucocorticoid treatment plan. Note: 1Intravenous methylprednisolone (IV MP) pulses are one dose weekly. 2Patients who started with rapid taper may be off prednisone.

Figure 2.

Methotrexate treatment plan. Notes: 1Intravenous methylprednisolone (IV MP) pulses are one dose weekly. 2Patients who started with rapid taper may be off prednisone. 3If condition worsens follow “Unchanged, Worse” pathway. 4If patient is intolerant of methotrexate, discontinue and add additional therapy.

Figure 3.

Anakinra treatment plan. Notes: 1Intravenous methylprednisolone (IV MP) pulses are one dose weekly. 2Patients who started with rapid taper may be off prednisone. 3If condition worsens or patient is intolerant of anakinra follow “Unchanged, Worse” pathway.

Figure 4.

Tocilizumab treatment plan. Notes: 1 Intravenous methylprednisolone (IV MP) pulses are one dose weekly. 2Patients who started with rapid taper may be off prednisone. 3If condition worsens or patient is intolerant of tocilizumab follow “Unchanged, Worse” pathway.

Table 2.

Suggested minimum data collection and assessment intervals1to be used with treatment plans

| Assessment Intervals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed Variables2 | Baseline Visit |

Follow-up visits: 1–2 weeks, 1 month, 3 month, 6 months, 9 months |

||

| History | ||||

| • Demographics | ||||

| ▪ DOB | ||||

| ▪ Gender | X | |||

| ▪ Race and ethnicity | ||||

| • Date(s) of onset of Symptoms | ||||

| ▪ Fever | X | |||

| ▪ Rash | ||||

| ▪ Joint symptoms | ||||

| • Pre-enrollment treatment history for SJIA |

X | |||

| • Current Medications and doses |

X | X | ||

| • Comorbid Diagnoses | X | |||

| • Fever of sJIA in the past week | X | X | ||

| • Rash of sJIA in the past week | X | X | ||

| • Duration of morning stiffness | X | X | ||

| • Serositis in the past week | X | X | ||

| • Patient has MAS (impression of treating physician) |

X | X | ||

| Patient reported outcomes and global assessments | ||||

| • Pain | X | X | ||

| • HRQOL | X | X | ||

| • Physical function | X | X | ||

| • Parent/patient global assessment of disease activity |

X | X | ||

| • Physician global assessment of disease activity |

X | X | ||

| Physical exam | ||||

| • Height, weight, BMI | X | X | ||

| • Rash | X | X | ||

| • Active joint count | X | X | ||

| • Lymphadenopathy | X | X | ||

| • Hepatomegaly | X | X | ||

| • Splenomegaly | X | X | ||

| • Serositis | X | X | ||

| Labs | ||||

| • CBC (wbc, hemoglobin, platelet count) |

X | X | ||

| • C-reactive protein | X | X | ||

| • Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | X | X | ||

| • Ferritin | X | X | ||

| • LDH | X | X | ||

| Treatment plan related items | ||||

| • Serious adverse events or important medical event |

X | |||

| • If plan discontinued, rationale | X | |||

| • Number of IV steroid pulses, if Any |

X | |||

| • Uveitis status at last eye exam | X | |||

Data is collected at baseline, 1–2 weeks, 1, 3, 6, 9 months. Data collection is encouraged at changes in treatment (even if it does not occur at a scheduled time point). Monthly phone follow-up recommended. Any additional visits in between these time points are at the discretion of the physician and data may or may not be collected.

Not included in table, malignancy and infection work-up, screen for tuberculosis at baseline (and then annually).

DISCUSSION

This is the first effort in pediatric rheumatology to develop consensus derived standardized treatment plans for the initial 9 months of treatment of new onset systemic JIA. These plans include recommendations on medication dosing and tapering of glucocorticoids along with a recommended schedule of visits and monitoring parameters. These plans are not intended to be identical to each individual clinician’s usual practices, but do represent the general and most common approaches to treatment of sJIA by pediatric rheumatologists across North America. Four different treatment plans were developed – glucocorticoid only, methotrexate, and 2 biologic DMARD based plans - anakinra, or tocilizumab -any of which can be used with the glucocorticoid treatment plan if necessary. These plans are intended for use by clinicians according to their clinical judgment and experience. The intent of these standardized treatment approaches is to reduce variation in treatments which, together with prospective data collection in a large number of patients, will facilitate comparative research of medication effectiveness, safety and tolerability in clinical practice. The opportunity to generate knowledge from this approach requires analytic methods to reduce bias, including confounding by indication. Given the current variability in treatment patterns evidenced by our surveys, we expect that each of the different plans will be adopted, thus resulting in patients with differing characteristics and levels of disease activity being treated with each plan. This variation in care can be used to advantage to identify the best clinical situations in which these treatment plans should be used. It is anticipated that as new evidence and therapeutics become available, the treatment plans will be updated and revised in an iterative fashion.

There were a number of important challenges in deriving these standardized treatment plans. These included the acknowledged heterogeneity of disease presentations and disease courses, as well as the heterogeneity of existing opinions regarding treatment, often based on personal experience and observation. While the project would ideally have created only a few standardized treatment plans to reduce the complexity of comparison, the anticipated availability of IL6 blockade could not be ignored as a likely effective treatment option. As a consequence, medications less commonly used in sJIA, such as TNF antagonists and calcineurin inhibitors, were not included in the treatment plans.

Additionally, the first ACR recommendations for the treatment of JIA were published in April 2011(4). There are notable differences between the standardized treatment plans and these recommendations, which were developed using different methodologies and sought to address different questions. One significant difference was the exclusion of tocilizumab from the ACR recommendations, because it was not commercially available at the time the recommendations were being formulated (3, 4). Another difference is that the guidelines consider the treatment of systemic features and treatment of arthritis in sJIA completely separately. In contrast, the consensus decision was that these clinical aspects could not practically be separated because systemic and arthritic features usually co-exist in new onset patients. In addition, while TNF inhibitors (20) and abatacept (21) are included in the ACR recommendations for the treatment of the arthritis features of sJIA, these treatments are not included in the standard treatment plans, again for similar reasons. Lastly, the treatment plans offer more specificity with regard to suggested medication dosing, evaluations, and anticipated time to treatment responses. A significant strength of the plans is that they were derived with the input of a larger and broader group of pediatric rheumatology clinicians.

There was extensive discussion about the development of the operational definition of patients who could be treated with the plans. It is recognized that many patients with sJIA in the early stages of disease do not strictly fulfill ILAR criteria, yet need treatment (22). Indeed, the Yamaguchi criteria for adult Still’s disease does not include arthritis as a criterion(23, 24). In order to capture as many patients with sJIA as possible while avoiding inclusion of patients with self-limited febrile illnesses or alternative diagnoses, it was ultimately decided to require at least two weeks of fevers, at least one joint with physician-documented arthritis, and at least one other feature compatible with the ILAR criteria for sJIA. It must be emphasized that care must be taken to exclude other diagnoses such as infection, malignancy or a different auto-inflammatory condition prior to using these plans, since there is no foolproof diagnostic test for sJIA, and these illnesses can be mistaken for sJIA. It is essential that these plans should be used only when the practitioner is extremely confident of the diagnosis of sJIA. Additionally, these plans are not meant to be proscriptive in either the choice of treatment plan or when the treatment plan should be initiated. Only the treating physician can decide whether one of the plans is appropriate for any given patient at any point in the disease course.

Other discussion points included the scope of the diagnostic evaluation, which is not specified in the treatment plans. SJIA is by necessity a diagnosis of exclusion, for which no specific tests are diagnostic. Given that not all patients with suspected sJIA will require a bone marrow aspiration, a PET scan, or other specific testing, the extent of exclusionary work-up must be left to the judgment of the treating physician. Another area of considerable debate included specifics of the dosing of methotrexate, anakinra and glucocorticoids (the initial dosing, rapidity of dose escalation, and routes of administration of these medications).

Limitations include that the treatment plans proposed do not go beyond the initial 9 months, and do not address medication tapering aside from glucocorticoids. New anti-IL1 agents will need to be incorporated as part of the anti-IL1 plan as they become available, along with modifications to account for any pharmacokinetic differences. Since the standard treatment plans are meant for use in routine clinical practice, the proposed variables and timing of data collection should be similar to the standard of care, yet able to effectively capture relevant health outcomes. Lastly, the standard treatment plans do not address the treatment or diagnosis of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), an important complication of sJIA, because there are currently no clinically useful standard definitions that are applicable to every patient. The treating physician must therefore be aware of the signs of possible MAS, which can cause rapid deterioration and even death in sJIA patients if not recognized and treated promptly. Signs and symptoms of MAS may include persistent fever, marked hyper-ferritinemia, inappropriate cytopenias (platelets, erythrocytes, and/or leukocytes), evidence of liver injury (e.g. elevated liver enzymes) and liver dysfunction (e.g. coagulopathy, synthetic blockage, elevated triglycerides) and CNS dysfunction(25). Note that these are not the only signs and symptoms of MAS, and not all symptoms may be present in any individual patient with MAS.

Conclusions

Four standardized treatment plans for new onset sJIA were developed with the goal of reducing variation in care and to ultimately facilitate evaluation of the comparative effectiveness of these treatments. These plans were found to be acceptable to the majority of survey respondents who are members of CARRA. Coupled with standardized data collection at routine intervals, widespread use of these treatment plans offers the potential to serve as the basis for rigorous study of comparative effectiveness of the regimens as used in clinical practice and to ultimately guide increased evidence-based decision-making for treatment of sJIA.

SIGNIFICANCE AND INNOVATIONS.

Use of standardized treatment protocols has radically improved outcomes of treatment for childhood malignancies. There is wide variation in treatment of children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), with no clear superior approach. Reducing variation and standardizing treatment plans coupled with data collection will enable relevant comparisons of treatments for sJIA in clinical practice.

CARRA is a clinical research network of more than 300 pediatric rheumatologists at 92 centers in North America. With funding from NIAMS, CARRA has developed with a combination of literature review, surveys and consensus meetings 4 standardized initial treatment approaches for systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

The treatment plans are not meant to be guidelines, but it is anticipated that with widespread adoption these can then serve as a benchmark against which new therapies/approaches can be compared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was completed with support from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease at the National Institutes of Health (NIH 1RC1AR058605-01, PI Wallace, Co-PI Ilowite), the Children’s Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA), the Arthritis Foundation, the Wasie Foundation and Friends of CARRA.

We express our appreciation for the contributions of the late Dr. Joyce Warshawsky to the sJIA workgroup.

We thank Edward Giannini, DrPH for assistance in planning and facilitating the April 2010 consensus meeting and Audrey Hendrickson for her administrative assistance.

Footnotes

Declared author relationships are as follows: R. Schneider, Hoffmann LaRoche; N. T. Ilowite, Abbott Immunology Pharmaceuticals, Genentech and Biogen IDEC Inc., Regeneron, Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation, Centocor, Inc.; C. A. Wallace, Amgen, BMS, Genentech, Pfizer; Y. Kimura, Genentech and Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation.

CARRA sJIA core workgroup members: Yukiko Kimura (Leader), Esi Morgan DeWitt (co-Leader), Timothy Beukelman, Peter Nigrovic, Karen Onel, Sampath Prahalad, Rayfel Schneider, Matthew Stoll, Joyce Warshawsky.

Contributing CARRA members: T. Brent Graham, Judyann Olson, Judy Smith, James Birmingham, Karen Watanabe Duffy, Edward Fels, Sheila Angeles-Han, Raphael Hirsch, Maria Ibarra, Lisa Imundo, Ginger Janow, Michael Miller, Diana Milojevic, Kabita Nanda, Marc Natter, Nancy Olson, Murray Passo, Michael Rapoff, Sarah Ringold, Tova Ronis, Margalit Rosenkranz, Kenneth N. Schikler, Susan Shenoi, David Sherry, Judith Smith, Steven Spalding, Lynn Spiegel, Tracy Ting, Theresa Wampler-Muskardin, Richard K. Vehe, Lawrence Zemel.

Additional consensus meeting attendees: Patient representatives: Vincent Del Gaizo, Anne Murphy. CARRA members: Ciaran Duffy, Norman Ilowite, Daniel Lovell, Betsy Mellins, Michael Rapoff, Susan Thompson.

References

- 1.Quartier P, Allantaz F, Cimaz R, Pillet P, Messiaen C, Bardin C, et al. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ANAJIS trial) Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 May;70(5):747–754. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yokota S, Imagawa T, Mori M, Miyamae T, Aihara Y, Takei S, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):998–1006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.FDA. FDA approves Actemra to treat rare form of juvenile arthritis. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. Apr 15, [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beukelman T, Patkar NM, Saag KG, Tolleson-Rinehart S, Cron RQ, DeWitt EM, et al. 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic features. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011 Apr;63(4):465–482. doi: 10.1002/acr.20460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Packham JC, Hall MA. Long-term follow-up of 246 adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: functional outcome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41(12):1428–1435. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.12.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassidy JT, Petty RE, Laxer RM, Lindsley CB, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Rheumatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh-Grewal D, Schneider R, Bayer N, Feldman BM. Predictors of disease course and remission in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: significance of early clinical and laboratory features. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(5):1595–1601. doi: 10.1002/art.21774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lomater C, Gerloni V, Gattinara M, Mazzotti J, Cimaz R, Fantini F. Systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a retrospective study of 80 consecutive patients followed for 10 years. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(2):491–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nigrovic PA, Mannion M, Prince FH, Zeft A, Rabinovich CE, van Rossum MA, et al. Anakinra as first-line disease-modifying therapy in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: report of forty-six patients from an international multicenter series. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Feb;63(2):545–555. doi: 10.1002/art.30128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spiegel LR, Schneider R, Lang BA, Birdi N, Silverman ED, Laxer RM, et al. Early predictors of poor functional outcome in systemic-onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(11):2402–2409. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2402::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoeber E. Prognosis in juvenile chronic arthritis follow-up of 433 children. Eur J Pediatri. 1981;135:225–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00442095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider R, Lang BA, Reilly BJ, Laxer RM, Silverman ED, Ibanez D, et al. Prognostic indicators of joint destruction in systemic-onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Pediatr. 1992;120(2 Pt 1):200–205. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russo RA, Katsicas MM. Global damage in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: preliminary early predictors. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(6):1151–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilowite NT, Laxer RM. Pharmacology and drug therapy. In: Cassidy JT, Petty RE, Laxer RM, Lindsley CB, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Rheumatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2011. pp. 71–126. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura Y, Pinho P, Walco G, Higgins G, Hummell D, Szer I, et al. Etanercept treatment in patients with refractory systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(5):935–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katsicas MM, Russo RA. Use of infliximab in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis refractory to etanercept. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(4):545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeft A, Hollister R, LaFleur B, Sampath P, Soep J, McNally B, et al. Anakinra for systemic juvenile arthritis: the Rocky Mountain experience. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15(4):161–164. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181a4f459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sox HC, Greenfield S. Comparative effectiveness research: a report from the Institute of Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(3):203–205. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CARRA. Proceedings of the Pediatric Rheumatology Research Annual Scientific Meeting; April 23–25, 2010; Chicago, IL: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horneff G, Schmeling H, Biedermann T, Foeldvari I, Ganser G, Girschick HJ, et al. The German etanercept registry for treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(12):1638–1644. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.014886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, Paz E, Rubio-Perez N, Silva CA, et al. Abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):383–391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60998-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Behrens E, Beukelman T, Gallo L, Spangler J, Rosenkranz M, Arkachaisri T, Ayala R, Groh B, Finkel TH, Cron RQ. Evaluation of the presentation of systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: data from the Pennsylvania Systemic Onset Juvenile Arthritis Registry (PASOJAR) J Rheumatol. 2008;35(2):343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu T, Kasukawa R, Mizushima Y, Kashiwagi H, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1992 Mar;19(3):424–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang L, Wang Z, Dai X, Jin X. Evaluation of clinical measures and different criteria for diagnosis of adult-onset Still's disease in a Chinese population. J Rheumatol. 38(4):741–746. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ravelli A, Magni-Manzoni S, Pistorio A, Besana C, Foti T, Ruperto N, et al. Preliminary diagnostic guidelines for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Pediatr. 2005;146(5):598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.