Abstract

KCNQ3 homomeric channels yield very small macroscopic currents compared with other KCNQ channels or KCNQ2/3 heteromers. Two disparate regions of the channels—the C-terminus and the pore region—have been implicated in governing KCNQ current amplitudes. We previously showed that the C-terminus plays a secondary role compared with the pore region. Here, we confirm the critical role of the pore region in determining KCNQ3 currents. We find that mutations at the 312 position in the pore helix of KCNQ3 (I312E, I312K, and I312R) dramatically decreased KCNQ3 homomeric currents as well as heteromeric KCNQ2/3 currents. Evidence that these mutants were expressed in the heteromers includes shifted TEA sensitivity compared with KCNQ2 homomers. To test for differential membrane protein expression, we performed total internal reflection fluorescence imaging, which revealed only small differences that do not underlie the differences in macroscopic currents. To determine whether this mechanism generalizes to other KCNQ channels, we tested the effects of analogous mutations at the conserved I273 position in KCNQ2, with similar results. Finally, we performed homology modeling of the pore region of wild-type and mutant KCNQ3 channels to investigate the putative structural mechanism mediating these results. The modeling suggests that the lack of current in I312E, I312K, and I312R KCNQ3 channels is due to pore helix-selectivity filter interactions that lock the selectivity filter in a nonconductive conformation.

Introduction

In the mammalian brain, voltage-gated KCNQ channels are key determinants in the regulation of neuronal resting membrane potentials, action potential duration, firing patterns, and neurotransmitter release (1). In neurons, KCNQ1-5 subunits underlie K+ currents with divergent macroscopic current amplitudes. Thus, there is a 10-fold difference in whole-cell current between KCNQ3 homomers and KCNQ4 homomers, or KCNQ2/3 heteromers (2,3). Two mechanisms have been postulated to underlie the KCNQ3 homomeric currents, which are small compared with other KCNQ homomers and KCNQ2/3 heteromers. The first involves differential channel expression, governed by the assembly domain of the distal C-terminus (4). The second suggests similar expression of KCNQ channels but a KCNQ3 pore that is particularly unstable (5,6).

Here, we further investigated the molecular determinants in KCNQ3 that are responsible for its small current, focusing on the pore helix-selectivity filter (SF) region. A number of lines of evidence support the idea that a network of interactions between the pore helix and the SF has a crucial effect on the gating of a number of K+ channels. Thus, the D378E point mutant in the pore helix of Kv2.1 affects its single-channel behavior (7). Moreover, mutations in the SF and pore helix of Shaker, hERG, and inward rectifiers also have effects on gating properties (8–11). In KCNQ3, replacement of an alanine (A315) in the pore helix of KCNQ3 with a hydrophilic threonine or serine increases current amplitudes by >15-fold (5,6,12). We previously suggested that this current augmentation arises from a stabilization of the SF in an open configuration mediated by a network of interactions between the lower part of the SF and the pore helix (I312 and A315T/S) (6). Cordero-Morales et al. (13,14) and Chakrapani et al. (15) showed that a single mutation in KcsA (E71), which is at the position equivalent to I312 in KCNQ3, to an alanine or an isoleucine leads to a disruption of the interaction between D80 and W67, stabilizing the SF in a conductive conformation by preventing an inactivation, likened to C-type inactivation in eukaryotic K+ channels, from occurring. Interestingly, a study involving homology modeling of KCNQ3 suggested that a similar interaction occurs between the equivalent residues (D321 and W308) in KCNQ3 (6). Taken together, these studies suggest that a similar network of interactions between the pore helix (I312) and the SF may be involved in KCNQ3 gating. The interactions of our earlier model clearly predict that I312 is critical for SF stabilization and channel permeation.

To test this prediction, we studied the effect of a series of mutations at the 312 position on KCNQ3 channels and the conserved I273 position in KCNQ2. Our results show that the hydrophilic substitutions I312/273E, I312/273K, and I312/273R dramatically decrease homomeric KCNQ3 or KCNQ2 current amplitudes, as well as those from heteromeric KCNQ2/3 channels, whereas substitution by a hydrophobic valine has no effect. Wild-type (WT) and mutant KCNQ3 surface expression were studied by total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, and the results show that the decrease of current amplitude by the pore region mutations results in only small differences in membrane expression of channels that do not underlie the differences in macroscopic current amplitudes. Finally, we performed homology modeling of WT and mutant KCNQ3 to understand the possible molecular mechanisms involved in the effect of the pore mutations. This homology modeling predicts that the decrease of current in KCNQ3 (I312E), (I312K), and (I312R) is due to electrostatic interactions between the top of the SF and the pore helix, which lock the channel in a nonconductive conformation. Our results suggest that a network of interactions between the pore helix and the SF controls KCNQ3 current amplitudes.

Materials and Methods

For details about the materials and methods used in this work, see the Supporting Material.

Results

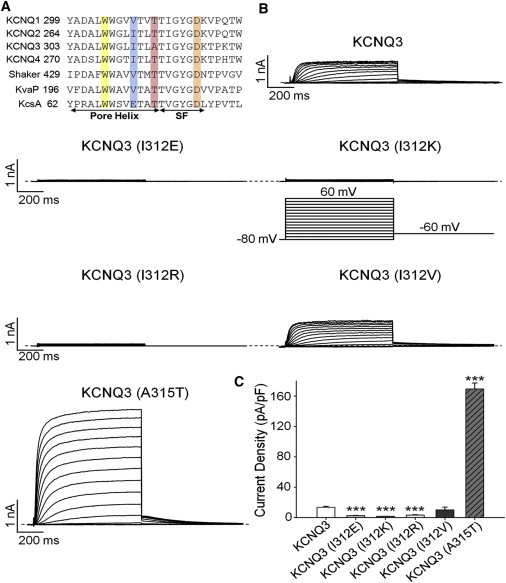

Hydrophilic residues at position 312 have dramatic effects on homomeric KCNQ3 currents

In a previous study (6), we showed that mutation of the A315 to a hydroxyl-containing residue, such as a threonine or a serine, increased macroscopic current amplitudes by ∼15-fold over WT KCNQ3 channels, representing a 25-fold increase in the density of functional channels. In that study, a homology model of the pore of KCNQ3 predicted critical interactions between the pore helix and the SF, involving hydrogen (H+)-bonds between the carbonyl oxygen atom of I312 and the SF. In WT KCNQ3 channels, this carbonyl is free to rotate, and the critical bonds it is predicted to make with SF residues are consequently unstable. However, the presence of the hydroxyl group of the threonine in the 315 position stabilizes the position of the carbonyl of I312 via an additional H+-bond with the hydroxyl, preventing the SF structure from locking closed. Most voltage-gated K+ channels have a hydrophobic residue at the analogous 312 position (Fig. 1 A), except for KcsA, which possesses a hydrophilic glutamate. To further investigate whether I312 is involved in the mechanism underlying KCNQ3 pore stability, we studied the effects of several mutations at this position. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were transiently transfected with cDNA coding for the appropriate channels, along with EGFP as a reporter for successful transfection. Fig. 1 B shows currents from cells expressing KCNQ3 homomers, either from WT subunits or from subunits with the I312E, I312K, I312R, I312V, and A315T mutations. Consistent with previous work (6), the A315T mutation in KCNQ3 strongly increased the current density by nearly 13-fold relative to WT KCNQ3 from 13.5 ± 1.2 pA/pF (n = 13) to 169 ± 8 pA/pF (n = 11, p < 0.001; Fig. 1 C). The I312K and I312R mutations both dramatically decreased the current density (Fig. 1 C). For cells transfected with KCNQ3 (I312K) and KCNQ3 (I312R) channels, the current densities at 60 mV were 1.6 ± 1.2 pA/pF (n = 10, p < 0.001) and 3.3 ± 0.5 pA/pF (n = 8, p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 1 C). The I312K and I312R mutations involve substitution of a large hydrophobic residue with a bulky hydrophilic residue. To determine whether side-chain size or hydrophobicity is more important, we also tested the effect of mutating I312 to either glutamate or valine. The former substitution maintains a large side-chain size but is hydrophilic, whereas the latter maintains hydrophobicity but decreases its side-chain size by one methyl group. We found that the I312E mutation also resulted in a dramatically decreased current density (2.5 ± 0.3 pA/pF, n = 8, p < 0.001) similar to the decrease seen in the I312K and I312R mutations. In contrast, the I312V mutation resulted in a current density (10.1 ± 3.7 pA/pF, n = 10; Fig. 1, B and C) similar to that of WT KCNQ3. These results suggest that a hydrophobic residue at this position is important for conferring WT current amplitudes. For KcsA, replacement of a glutamate at position 71 with a hydrophobic residue (alanine, valine, or isoleucine) leads to the stabilization of the SF in a conductive conformation (13,14), suggesting that a similar mechanism may be involved. Due to the small amplitude of all homomeric KCNQ3 currents, except for the A315T mutant, we were not able to assess changes in channel voltage dependence induced by the I312 mutants; however, we do make such assessments below for the heteromeric channels and for I312 mutants made in the KCNQ3 (A315T) background.

Figure 1.

Effects of mutations located in the pore region on KCNQ3 currents. (A) Sequence alignment of the pore region investigated in this study. Shown from the pore helix to the proximal part of the sixth transmembrane domain (S6) is an alignment of KCNQ1-4, Shaker, KcsA, and KvAP. Blue and red indicate residues at positions 312 and 315, respectively. Yellow and orange indicate residues at positions 308 and 321, respectively. (B) Representative perforated patch-clamp recordings from CHO cells transfected with WT KCNQ3, KCNQ3 (I312E), KCNQ3 (I312K), KCNQ3 (I312R), KCNQ3 (I312V), and KCNQ3 (A315T). As shown in the inset, cells were held at −80 mV and voltage steps were applied from −80 to 60 mV in 10 mV increments. (C) Bars show summarized current densities at 60 mV for the indicated channel under perforated patch-clamp (n = 8–13; ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

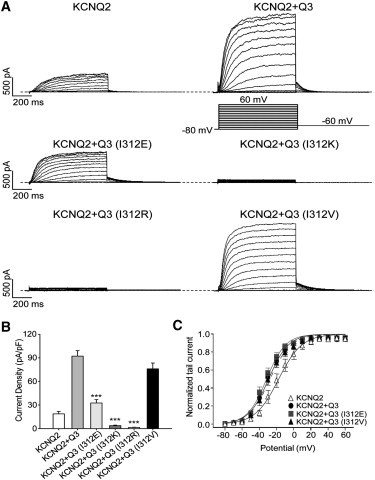

Hydrophilic residues at position 312 in KCNQ3 also reduce current amplitudes from heteromeric KCNQ2+Q3 currents

We then studied whether KCNQ3 (I312E, I312K, and I312R) mutant subunits coexpressed with WT KCNQ2 would yield smaller currents than those from KCNQ2+WT KCNQ3. Fig. 2 A shows representative currents from the indicated channels. Coexpression of KCNQ3 (I312E) with KCNQ2 decreased the current density by nearly threefold relative to KCNQ2 + WT KCNQ3, from 92 ± 7 pA/pF (n = 12) to 33 ± 4 pA/pF (n = 7; Fig. 2 B). The current densities from KCNQ2+KCNQ3 (I312K) and KCNQ2 + KCNQ3 (I312R) were even more reduced, to 3.7 ± 0.7pA/pF (n = 7, p < 0.001) and 1.5 ± 0.3 pA/pF (n = 13, p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 2 B). These results suggest that the effect of these three mutations from a hydrophobic to hydrophilic residue in KCNQ3 subunits decreases currents when they are present as heteromers with KCNQ2, as well as when they are homomeric. On the other hand, coexpression with KCNQ2 of KCNQ3 (I312V), which did not reduce homomeric currents, also did not significantly decrease the current density when they were expressed as heteromers (76 ± 7 pA/pF, n = 9; Fig. 2 B).

Figure 2.

Effects of mutations located in the pore region on KCNQ2/3 currents. (A) Representative perforated patch-clamp recordings from CHO cells transfected with KCNQ2 + KCNQ3 (WT or mutants). The pulse protocol used is as described in Fig. 1. (B) Bars show summarized current densities at 60 mV for the indicated channel (n = 7–13; ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (C) Voltage dependence of activation quantified by the normalized amplitude of the tail currents at −60 mV, plotted against the test potential (n = 7–12).

To assay changes in the voltage dependence of activation of the heteromeric channels induced by these mutants, we performed a tail current analysis in which the amplitude of the tail current at −60 mV was quantified as a function of the prepulse potential (Fig. 2 C). We found that none of the KCNQ3 mutants significantly changed the voltage dependence of activation compared with the WT heteromers. For cells transfected with KCNQ2 + WT KCNQ3, KCNQ2 + KCNQ3 (I312E), and KCNQ2 + KCNQ3 (I312V), the half-activation potentials were −30 ± 3 mV (n = 12), −31 ± 3 mV (n = 7), and −28 ± 3 mV (n = 9), respectively. In these coexpression experiments, we needed to confirm that both KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 (WT or mutant) subunits were being incorporated into the channel tetramers, i.e., that the changes in current densities observed were not due to omission of KCNQ3 subunits and expression of only KCNQ2 homomers. To verify this, we exploited the very different sensitivity of KCNQ2 homomers, KCNQ3 homomers, and KCNQ2/3 heteromers to external tetraethylammonium ions (TEA+) (16,17). Thus, KCNQ2 homomers are substantially blocked at 0.1 mM TEA+, with almost full block at 1 mM, whereas KCNQ3 homomers are negligibly blocked at 1 mM and less than half blocked at 100 mM TEA+, with KCNQ2/3 heteromers displaying an intermediate TEA+ sensitivity. We determined the TEA+ sensitivity for each group of coexpressed subunits. TEACl was applied over a range of concentrations, and the block of the currents was quantified at −20 mV. Our previous work indicated that coexpressed KCNQ2 + KCNQ3 or KCNQ3 + KCNQ4 subunits coassemble with a random stoichiometry governed by the binomial distribution (16,18). Because the resulting dose-response curves are somewhat complex, we approximated the sensitivity by fitting the data to a single Hill equation, which is sufficient to clearly distinguish between homomeric and heteromeric currents. Coexpression of KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 (I312E) produced currents with a TEA+ sensitivity intermediate between KCNQ2 and KCNQ2 + WT KCNQ3, whereas the dose-response curve for KCNQ2 + KCNQ3 (I312V) was unchanged (Fig. S1). Because the predicted IC50 values for channels with two KCNQ2 and two KCNQ3 subunits are higher than those for channels with three KCNQ2 and one KCNQ3 subunits (16), the slightly higher TEA+ sensitivity of KCNQ2 + KCNQ3 (I312E) could be due to a skewed stoichiometry of KCNQ2 subunits in the KCNQ2 + KCNQ3 (I312V) heteromers. Alternatively, the I312V mutation could alter the TEA+ sensitivity of KCNQ3. However, we conclude that both KCNQ3 (I312E) and (I312V) are substantially expressed as heteromers with KCNQ2.

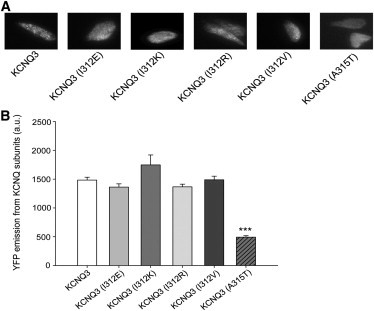

Small differences in plasma-membrane expression of KCNQ3 mutant channels do not explain the effect of pore-region mutations on current amplitudes

We then wished to determine whether the dramatic decrease in the current density of KCNQ3 (I312E), KCNQ3 (I312K), and KCNQ3 (I312R) homomers is due to a decrease in the abundance of channels present in the membrane. To answer this question, we measured the plasma-membrane expression of WT and mutant KCNQ3 by using TIRF microscopy, which isolates emissions from fluorophores in or within 300 nm of the membrane (19). Yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-tagged WT and mutant KCNQ3 were expressed in CHO cells and TIRF images of the various groups of cells were obtained. Fig. 3 A shows representative images of cells transfected with YFP-tagged WT or mutant KCNQ3 channels. The emission was quantified as mean pixel intensity over the surface area of the cell. The data are summarized in Fig. 3 B, revealing only minor differences in membrane expression between KCNQ3 WT and the KCNQ3 I312E, I312R, and I312V mutants. These small differences in surface expression are >10-fold too small to underlie the large difference in the current densities of the WT and mutant KCNQ3 channels. We conclude that the differential membrane abundance of channel protein does not underlie the differences in macroscopic current amplitudes.

Figure 3.

TIRF microscopy indicates that pore region mutations result in only small differences in membrane expression of channels. (A) Shown are fluorescent images under TIRF microscopy of CHO cells expressing the indicated YFP-tagged channels. In all cases, CHO cells were transfected with a total of 2 μg cDNA. The emission was quantified as the mean pixel intensity over the surface area of the cell. (B) Bars show summarized data for each channel type (n = 43–131; ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

Findings from our laboratory suggest that the increase of KCNQ3 current density by A315T or A315S mutations may be due to a stabilization of the SF into a conductive conformation rather than to an increase of expression at the plasma membrane (6), which is somewhat contrary to a recent publication (12). To revisit this question, we again compared the membrane expression of KCNQ3 WT and mutant (A315T) channels via TIRF microscopy, and obtained similar results. Indeed, although the currents from KCNQ3 (A315T) channels are much larger than those from WT KCNQ3, the TIRF emission from the former was ∼2-fold lower than the latter (Fig. 3 B). This is divergent from the results of Gómez-Posada and co-workers (12), who observed a twofold increase in the number of YFP-tagged WT KCNQ3 channels at the plasma membrane when coexpressed with KCNQ3 (A315T), assayed by TIRF microscopy. However, we would point out that such a small increase also cannot explain the ∼15-fold increased current density induced by the A315T mutation. In conclusion, we find that the A315T mutation only weakly affects the number of KCNQ3 channels at the plasma membrane, whereas the current density is dramatically increased. The data presented here reinforce the conclusion that the A315T mutation does not increase current amplitudes by a correlative increase in the expression of channels in the membrane.

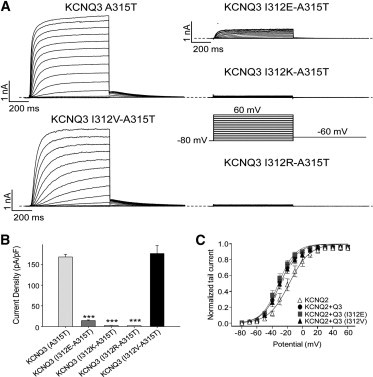

Hydrophilic residues at position 312 also strongly decrease KCNQ3 (A315T) currents

We previously suggested that augmentation of functional, conductive KCNQ3 channels is made possible by an interaction between the hydroxyl group of a substituted hydrophilic threonine or serine at the 315 position and the carbonyl oxygen of the isoleucine at the 312 position, which stabilizes the SF in a conductive conformation (6). Because all amino acids possess such a carboxylate group, one might think this interaction should be impervious to substitution. To test this, we examined the effect of substitution of I312 by arginine, glutamate, lysine, or valine in the KCNQ3 mutant (A315T) background. However, the effects of these mutations on current amplitudes were strikingly different and depended on the nature of the residues. The positively charged I312K and I312R mutations in the A315T background nearly abolished the currents, and the negatively charged I312E substitution strongly decreased the current density (Fig. 4, A and B). For cells transfected with KCNQ3 (A315T), (I312E-A315T), (I312K-A315T), and (I312R-A315T) subunits, the current densities at 60 mV were 168 ± 6 pA/pF (n = 14), 14 ± 2 pA/pF (n = 12, p < 0.001), 2.3 ± 0.2 pA/pF (n = 13, p < 0.001), and 2.6 ± 0.4 pA/pF (n = 8, p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 4 B). In contrast, substitution of I312 with a hydrophobic valine had no significant effect on the KCNQ3 (A315T) current density (176 ± 20 pA/pF, n = 14). We again analyzed the effects of these mutants on the voltage dependence of activation by using tail-current analysis (Fig. 4 C), which revealed little change in the voltage dependence of activation compared with KCNQ3 (A315T). Thus, only the presence of the valine at the 312 position seems not to alter the upregulation of current amplitudes induced by the introduction of a threonine at the 315 position. Our results show that a hydrophilic residue at the 312 position dramatically decreased WT KCNQ3 currents as well as those of KCNQ3 (A315T), whereas a hydrophobic residue at I312 does not. Hence, a hypothesis would be that the interaction between the hydroxyl of the threonine and the carbonyl of all tested residues still exists, but another mechanism common to WT and (A315T) KCNQ3 channels is responsible for the decrease of currents by substitution of I312 with the charged residues, a mechanism that does not occur with I312V.

Figure 4.

Effects of mutations at position 312 on KCNQ3 (A315T) currents. (A) Representative perforated patch-clamp recordings of the KCNQ3 (A315T), KCNQ3 (I312E-A315T), KCNQ3 (I312K-A315T), KCNQ3 (I312R-A315T), and KCNQ3 (I312V-A315T) channels. The pulse protocol used is as described in Fig. 1. (B) Bars show summarized current densities at 60 mV for the indicated channel (n = 8–14; ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (C) Voltage dependence of activation quantified by the normalized amplitude of the tail current at −60 mV, plotted against the test potential (n = 7–13).

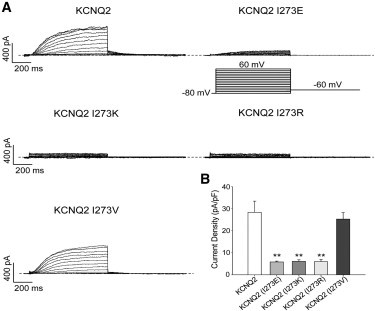

Hydrophilic residues at position 273 in KCNQ2 also decrease currents

Given the high degree of sequence similarity between the pore regions of KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 (Fig. 1 A), including the critical residues identified in this study, one would expect similar mechanisms of pore stabilization to apply to both channels. Thus, we tested the effects of mutation of the conserved isoleucine at the analogous 273 position of KCNQ2. As for KCNQ3, replacement of I273 with the hydrophobic valine had no effect on homomeric current amplitudes. However, substitution of I273 with a glutamate, a lysine, or an arginine sharply reduced them (Fig. 5 A), in parallel with the effects of such hydrophilic substitutions seen for I312 in KCNQ3. For KCNQ2 WT, (I273V), (I273E), (I273K), and (I273R), the current densities were 28.4 ± 5.1 pA/pF (n = 10), 25.3 ± 3.0 pA/pF (n = 7), 5.8 ± 0.4 pA/pF (n = 7, p < 0.01), 6.1 ± 0.7 pA/pF (n = 7, p < 0.01), and 6 ± 1 pA/pF (n = 7, p < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 5 B). These results suggest that the mechanisms of pore stabilization likely apply generally to the family of KCNQ channels, and not just KCNQ3 specifically.

Figure 5.

Effects of I273 mutations on homomeric KCNQ2 currents. (A) Representative perforated patch-clamp recordings from cells transfected with WT or mutant KCNQ2 channels. The pulse protocol used is as described in Fig. 1. (B) Bars show summarized current densities at 60 mV for the indicated channels (n = 7–10; ∗∗p < 0.01).

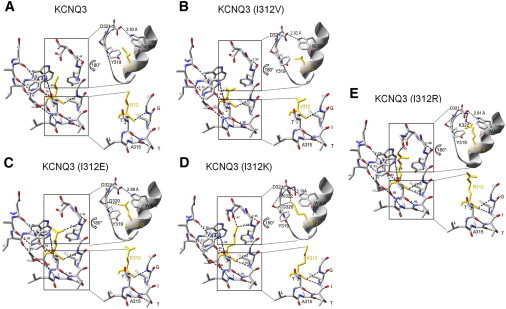

Structural homology modeling of the pore region suggests that a hydrophilic residue stabilizes the SF in a nonconductive conformation

To gain insight into the possible structural mechanism revealed by our mutagenesis of I312 of either KCNQ3 WT or A315T channels, we performed homology modeling of the region around the pore of WT and mutant KCNQ3 channels using the solved crystal structure of the bacterial voltage-gated K+ channel, KvAP (20), as a template. We chose KvAP as our primary template for our modeling, instead of KcsA, because it has the most conserved sequence similarity with KCNQ3 in the region between S5 and S6. Fig. 6 shows the full network of predicted H+-bonding interactions within and between the pore helix and the SF of WT and mutant KCNQ3 channels studied in this work. We focused our attention on two potentially critical hotspots. The first is at the lower part of the pore helix and the SF, the locus where we have hypothesized that the A315T/S mutations exert their stabilizing effect. However, the homology model predicts that none of the mutants will affect interactions between the lower pore helix and the lower SF (Fig. 6, bottom insets).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the structure of the SF region of WT and KCNQ3 mutants predicted by homology modeling and the predicted H+-bonding networks within the pore region. Shown are the predicted structures and the H+-bonds within and between the pore helix and the SF. The predicted distances (Å) between donor and acceptor for each bond are indicated. In the inset are shown expanded views (rotated by 180°) of the predicted interactions between the top of the SF and the pore helix (top), and the mini-network of predicted interactions between the GIT of the SF and the pore helix (bottom), in the area around I312.

The second hotspot is a network of interactions between the pore helix and the top of the SF. Cordero-Morales and co-workers (13) showed that a carboxyl-carboxylate interaction between D80 and E71 (D321 and I312 in KCNQ3), highlighted by the high-resolution structure of KcsA (21), was eliminated by the replacement of a hydrophilic residue by a hydrophobic one at position 71 (E71A). This substitution led to the reorientation of D80, destabilizing interactions between D80 and W67 (W308 in KCNQ3) and D80 and E71 (13). Our homology modeling of KCNQ3 does not predict a destabilization of interactions between D321 and W308 by any of the I312 mutations studied. For WT KCNQ3, I312E, I312K, I312R, and I312V, the predicted distances between D321 and W308 are 2.93 Å, 2.89 Å, 3.19 Å, 2.91 Å, and 2.92 Å, respectively (Fig. 6, top insets). The interaction between the oxygen atom of D321 and the nitrogen in the aromatic ring of W308 predicted in WT KCNQ3 channels is still present in all KCNQ3 mutant 312 channels. However, another network of interactions between the pore helix and the top of the SF is predicted in KCNQ3 mutants that have a hydrophilic residue at position 312 (I312E, I312K, and I312R). The predicted structure of I312E shows H+-bonds between an oxygen of E312 and the nitrogen of G320 (Fig. 6 C), and that of I312K reveals an H+-bond between a nitrogen of K312 and the nitrogen of G320 and with one of K322 (Fig. 6 D). Finally, for the I312R mutant, an interaction is predicted to occur between a nitrogen of R312 and an oxygen of K322 (Fig. 6 E). This network of interactions between the pore helix and the top of the SF is predicted to be wholly absent in WT and I312V channels. Thus, the modeling suggests that a hydrophilic residue at the 312 position promotes a nonconductive conformation by interacting with the top of the SF, in similarity to the mechanism of pore destabilization suggested for KcsA channels.

The SF of KcsA has five known sites of permeant ion occupancy (21). An examination of analogous residues in KCNQ3 indicates that the distance between G320 of each subunit is critical for the first ion-binding site (S1). Indeed, several studies have suggested that a nonconductive conformation of K+ channels is due to a constriction of the SF at the level of the S1 binding site (14,22,23). In addition, Y319 in KCNQ3 corresponds to the residue that is known to partly coordinate the second ion-binding site (S2) of the SF in KcsA (24), which is hypothesized to collapse in the absence of permeant ions (25,26). Consequently, we also examined whether the I312 mutations affected the distance between diagonally opposing residues in the SF (Table S1). The predicted distances between the carbonyls of GYGI residues from diagonally facing subunits in WT and mutant KCNQ3 show that the distance between opposing Y319 is not modified by any of the substituted residues at the 312 position, whereas that between opposing G320 carbonyls decreases from 6.92 Å in WT KCNQ3 to 5.9 Å and 6.01 Å in KCNQ3 (I312K) and KCNQ3 (I312R), respectively. These predictions suggest a constriction of the SF at the level of the S1 binding site induced by hydrophilic substitutions at I312. However, the I312E mutation, which strongly decreased KCNQ3 currents, is not predicted to affect the distance between opposing G320 carbonyls. This distance is smaller than that of WT KCNQ3 (6.74 Å), but similar to that of KCNQ3 (I312V) (6.71 Å), which had no effect on KCNQ3 homomeric currents. Thus, we conclude that the shortened distance at the level of S1 binding site is not the critical factor implicated in the effect of the 312 mutations; rather, it is more likely a rearrangement of the SF structure due to H+-bonds between the pore helix and the top of the SF.

Given the parallels that we suggest here between the mechanisms governing pore stability in KCNQ3 and KcsA, we repeated the modeling described above using the pore structure of KcsA (21) instead of the pore of KvAP as a template. The results of the KcsA model are similar to those obtained using KvAP, including a parallel predicted network of interactions between the pore helix and the top of the SF for the I312 KCNQ3 hydrophilic mutants (I312E, I312K, and I312R), but not for KCNQ3 WT or (I312V) (Fig. S2, A and B, top insets). For the I312E mutant, the KcsA-based model predicts H+-bonds between an oxygen of E312 and a nitrogen atom of Y319, instead of G320 (Fig. S2 C, top inset). The predicted structure of I312K in the KcsA-based model predicts an H+-bond between a nitrogen of K312 and a nitrogen of K322, whereas that of I312R predicts an H+-bond between the nitrogen of R312 and an oxygen of K322 (Fig. S2, D and E, top insets). Thus, using either the pore of KvAP or that of KcsA as a template, hydrophilic residues at the 312 position of KCNQ3 are predicted to interact with the top of the SF, which we suggest causes destabilization of the pore and nonfunctional channels.

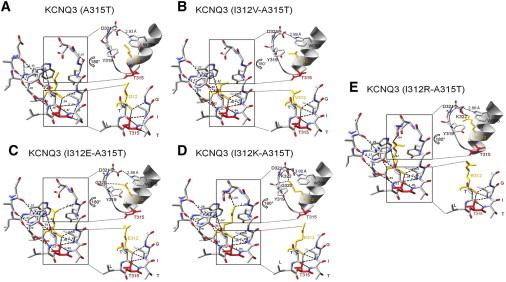

Interestingly, the same hydrophilic substitutions at the 312 position that dramatically decreased WT KCNQ3 current densities also strongly reduced those of the normally high-expressing A315T mutant current. As for the WT KCNQ3 channels, substitution of a hydrophobic residue had no effect on A315T current amplitudes, suggesting that a common structural mechanism is involved in the decrease of KCNQ3 WT and (A315T) currents. To investigate this hypothesis, we performed further homology modeling for the KCNQ3 mutant (A315T) and all double mutants (I312-A315T), as we did for the I312 mutants of WT KCNQ3, using the pore of KvAP as template. We examined the structure of the pore helix and the SF in the two hotspots described above. The predicted structure shows that H+-bonds between the carbonyl of the residue at the 312 position and the hydroxyl group of the threonine at the 315 position, and also with nitrogen of G318, are still present regardless of the residue at the 312 position (Fig. 7, bottom insets). Again, none of the 312 mutations are predicted to disrupt the interactions between the pore helix (D321 and I312) and W308 (Fig. 7, top insets). Finally, as for the I312 mutants in the KCNQ3 WT background, there are predicted new interactions for the hydrophilic I312 mutants in the A15T background between the pore helix and the top of the SF, involving the same H+-bonds as those described for KCNQ3 (I312E), (I312K), and (I312R) (Fig. 7, C–E). For all of the mutants in the A315T background, there is an additional H+-bond predicted between I312 and I317, which is likely not important.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the structure of the SF region of KCNQ3 mutant (A315T) in the absence or presence of mutations at the 312 positions, predicted by homology modeling and the predicted H+-bonding networks within the pore region. Shown are the predicted structures and the H+-bonds within and between the pore helix and the SF. The predicted distances (Å) between donor and acceptor for each bond are indicated. In the inset are shown expanded views (rotated by 180°) of the predicted interactions between the top of the SF and the pore helix (top), and the mini-network of predicted interactions between the GIT of the SF and the pore helix (bottom), in the area around I312 and T315.

We also determined the predicted distances between the diagonally opposing residues in the SF (Table S2). As for the KCNQ3 WT channels, the distance between opposing Y319 is not modified in the presence of a hydrophilic residue at the 312 position, whereas that between opposing G320 is shortened. However, that distance is also reduced by a hydrophobic residue at this position (V312; Table S2), which had no effect on KCNQ3 A315T currents. This reinforces the proposition that a rearrangement of the SF structure underlies the effects seen here, rather than a constriction of the SF at the level of the S1 binding site. These models suggest that a common mechanism affects KCNQ3 WT as well as KCNQ3 (A315T) homomers. We conclude that most KCNQ3 (I312E), (I312K), and (I312R) channels are in a nonconductive conformation because of a network of H+-bonds between the hydrophilic residue at the 312 position in the pore helix and the top of the SF, both for WT KCNQ3 and for the normally high-expressing (A315T) mutant.

Discussion

The work presented here supports the view that the pore region is critical for governing KCNQ3 current amplitudes. Consistent with this notion, replacement of a hydrophobic residue (an isoleucine in WT KCNQ3) with a charged hydrophilic residue (glutamate, arginine, or lysine) at the 312 position, in the pore helix, strongly decreased KCNQ3 homomeric current amplitudes. In contrast, substitution to a smaller hydrophobic residue, a valine, produced a K+ current similar to that of WT KCNQ3 channels. Similar effects of these residues were observed when they were coexpressed with WT KCNQ2, and also in the KCNQ3 (A315T) mutant that boosts KCNQ3 homomeric current densities by ∼15-fold. We previously suggested that a threonine or serine at the 315 position stabilizes the SF in a conductive conformation by the creation of a network of H+-bonds around I312. Without this stabilization, the SF is predicted to be unstable and likely to collapse (6). This hypothesis suggests that I312 is critical for the pore stability of KCNQ3 channels, both for WT KCNQ3 and for the A315T mutant. Thus, we investigated the effects of diverse mutations at that residue. We found that substitution of I312 by any charged hydrophilic residue nearly abolished the currents of both WT and KCNQ3 (A315T) homomers, and reduced the currents of KCNQ2/3 heteromers, whereas substitution of a valine had no effect. None of the mutations exerted any significant effect on voltage dependence, and TIRF measurements revealed only small differences in surface expression among the channels, which cannot explain the vast differences in macroscopic current amplitudes. Similar effects were seen for the conserved I273 residue in KCNQ2, suggesting conserved mechanisms of pore stability among KCNQ channels (and likely K+ channels in general).

Our homology modeling is predicated on the likely similar structural mechanisms by which the pores of K+ channels work in organisms ranging from prokaryotes to mammals, although we acknowledge that there may be salient differences among their pore functions. However, a study that specifically compared the molecular interactions underlying structural mechanisms of the pore regions of KcsA and Kv1.2 (Shaker) found them to be highly congruent (27). Our modeling suggests that a common feature of the hydrophilic I312E, I312K, and I312R, but not the hydrophobic I312V, substitutions is the induced presence of interactions between these substituted residues at the 312 position and Y319, G320, and D321 at the top (extracellular side) of the SF. Could such interactions lock channels in a nonconductive conformation and make most KCNQ3 homomers dormant? Several studies are consistent with this idea. The high-resolution structure of the KcsA SF and mutagenesis studies have shown that the stability of the SF is modulated by a series of interactions, including H+-bonds between residues W67 and E71 in the pore helix and D80 at the top of the SF (13,14,21). Disruption of at least one of these interactions relieved a type of inactivation likened to C-type in Shaker channels, stabilizing KcsA channels in a conductive conformation (13,14). We suggest that an equivalent mechanism controls KCNQ3 pore stability, although the effects of WT and mutant residues at the 71/312 position are reversed. Thus, KcsA has a glutamate at the 71 position, resulting in interactions between the pore helix and the top of the SF in WT channels, whereas KCNQ3 has an isoleucine at the analogous 312 position, precluding this interaction in WT channels. Substitution of E71 to I or V in KcsA prevents those interactions (13,15), in similarity to the absence of this interaction in WT KCNQ3 and in the I312V mutant. Thus, although the particular residues between KcsA and KCNQ3 channels differ, we suggest that they share a common structural mechanism whereby the presence of interactions between the pore helix and the top of the SF destabilizes the pore, and their absence promotes pore stability.

Several studies reinforce this correlation for K+ channels in general. The E71-D80 interaction in KcsA is absent in almost all Kv channels. Most of these channels possess a valine or an isoleucine, as does KCNQ3, in the position equivalent to E71 in KcsA, which is thus unable to engage in a direct interaction with the residue equivalent to D80 in KcsA. For example, Cordero-Morales and co-workers (14) tried to recreate this mechanism in KcsA for Kv1.2 channels, which possess a valine at position 370, analogously to E71 in KcsA. Thus, replacement of V370 in Kv1.2 with a hydrophilic glutamate, serine, or histidine promoted C-type inactivation to varying degrees, or (in the case of V370H) completely nonfunctional channels. These data are consistent with Kv function being generally regulated by interactions between residues in the pore helix and the top of the SF. Another important interaction at this locus that seems conserved among K+ channels and involved in C-type inactivation occurs between W67 and D80 in KcsA. The analogous interaction pairs in Shaker, W434, and D447, and in mammalian Kv1.2 (W366-D379) have been shown to also interact strongly (27). However, a recent study showed that disrupting these interactions in both Shaker and Kv1.2 affected pore stability and altered the likelihood that channels would be in a nonconductive conformation (28), although in ways divergent from KcsA. Indeed, substitution of tryptophan with a phenylalanine abolished currents in Shaker and in Kv1.2, whereas the equivalent mutation in KcsA strongly accelerated C-type inactivation, which is very modest for both WT channels. Our homology modeling also predicts an H+-bond between the analogous residues of KCNQ3 (W308-D321), reinforcing the parallel between KcsA and KCNQ channels. However, this interaction does not seem to be a key factor in KCNQ3 stability, because it is predicted to be nearly identical for WT KCNQ3 and all the mutants analyzed. This suggests that these pore-helix-SF interactions are critical for C-type inactivation in KcsA and perhaps Shaker-type channels as well. However, C-type inactivation per se is not responsible for the decrease of current densities observed in the KCNQ3 (I312E), (I312K), and (I312R) mutants, because we do not observe a time-dependent decrease in the macroscopic current or a reduction in the single-channel open probability, which is the hallmark of an inactivation process. Moreover, C-type inactivation has been associated with a constriction of the SF at the level of the S1 binding site, leading to a shortening of the distance between opposing G320 carbonyls (14,22,23). In our homology models, we did not observe significant differences in the distance between opposing facing carbonyls in the SF that correlated with the current densities of channels. The I312K and I312R decreased the distance between opposing G320 carbonyls, but although that distance for the I312E mutant is not predicted to be significantly decreased, the currents from I312E were tiny, ruling out classical C-type inactivation. This conclusion is consistent with our other classical tests of C-type inactivation in our previous work (6). However, we suggest that the stability of the pore of KCNQ3 channels, as for the other K+ channels discussed here, is dramatically decreased by interactions between the pore helix and the top of the SF, which results in most such channels being assembled in a nonconductive, nonfunctional conformation.

The destabilizing effect of interactions between the pore helix and the top of the SF stands in stark contrast to the stabilizing effect of such interactions at the bottom (cytoplasmic side) of the SF. As discussed above, substitution of the endogenous alanine at position 315 at the bottom of the pore helix with a threonine or a serine strongly increases current densities in a manner that is not involved in increased expression of channels at the membrane (5,6). We modeled the effect of the A315T,S mutations as being due to T315 or S315 inducing a stronger interaction between the I312 studied here and the bottom of the SF, stabilizing KCNQ3 channels in a conductive conformation. Thus, interactions of the pore helix and the SF have opposite effects on pore stability, depending on which side of the SF the interaction occurs. Interestingly, our data showing that the I312K, I312R, and I312E mutants have equal effects when introduced into the A315T background indicate that the destabilizing effects at the top of the SF are dominant over the stabilizing effects at the bottom. We postulate that a hydrophilic residue at the 312 position destabilizes the SF and locks channels in a nonconductive conformation by interacting with the top of the SF, and this interaction both prevents WT KCNQ3 from functioning and interferes with normal channel gating when incorporated with KCNQ2 as heteromers. This action cannot be rescued or overcome by the stabilizing action of the A315T mutation at the bottom of the SF. In our companion study to follow, we will explore a critical effect of interactions between F344 in S6 and the pore helix, which is also modeled as being critical for pore stability. Thus, we suggest that differences in these networks of interactions explain the large variability of current amplitudes throughout KCNQ channels or KCNQ2/3 heteromers, a variability that is likely critical for the neurophysiological effect of the different KCNQ channel compositions on excitable cells in nerve, cardiac tissue, and muscle.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pamela Reed for expert technical assistance. All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 NS043394 and R01 NS065138.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Jentsch T.J. Neuronal KCNQ potassium channels: physiology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2000;1:21–30. doi: 10.1038/35036198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kubisch C., Schroeder B.C., Jentsch T.J. KCNQ4, a novel potassium channel expressed in sensory outer hair cells, is mutated in dominant deafness. Cell. 1999;96:437–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gamper N., Stockand J.D., Shapiro M.S. Subunit-specific modulation of KCNQ potassium channels by Src tyrosine kinase. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:84–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00084.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwake M., Athanasiadu D., Friedrich T. Structural determinants of M-type KCNQ (Kv7) K+ channel assembly. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:3757–3766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5017-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Etxeberria A., Santana-Castro I., Villarroel A. Three mechanisms underlie KCNQ2/3 heteromeric potassium M-channel potentiation. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:9146–9152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3194-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaika O., Hernandez C.C., Shapiro M.S. Determinants within the turret and pore-loop domains of KCNQ3 K+ channels governing functional activity. Biophys. J. 2008;95:5121–5137. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.137604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman M.L., Blanke M.L., VanDongen A.M. Allosteric effects of external K+ ions mediated by the aspartate of the GYGD signature sequence in the Kv2.1 K+ channel. Pflugers Arch. 2006;451:776–792. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ficker E., Jarolimek W., Brown A.M. Molecular determinants of dofetilide block of HERG K+ channels. Circ. Res. 1998;82:386–395. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yifrach O., MacKinnon R. Energetics of pore opening in a voltage-gated K(+) channel. Cell. 2002;111:231–239. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu T., Ting A.Y., Yang J. Probing ion permeation and gating in a K+ channel with backbone mutations in the selectivity filter. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:239–246. doi: 10.1038/85080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alagem N., Yesylevskyy S., Reuveny E. The pore helix is involved in stabilizing the open state of inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Biophys. J. 2003;85:300–312. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74475-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gómez-Posada J.C., Etxeberría A., Villarroel A. A pore residue of the KCNQ3 potassium M-channel subunit controls surface expression. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:9316–9323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0851-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordero-Morales J.F., Cuello L.G., Perozo E. Molecular determinants of gating at the potassium-channel selectivity filter. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:311–318. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordero-Morales J.F., Jogini V., Perozo E. Molecular driving forces determining potassium channel slow inactivation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:1062–1069. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chakrapani S., Cordero-Morales J.F., Perozo E. On the structural basis of modal gating behavior in K(+) channels. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:67–74. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapiro M.S., Roche J.P., Hille B. Reconstitution of muscarinic modulation of the KCNQ2/KCNQ3 K(+) channels that underlie the neuronal M current. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:1710–1721. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01710.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadley J.K., Noda M., Brown D.A. Differential tetraethylammonium sensitivity of KCNQ1-4 potassium channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:413–415. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bal M., Zhang J., Shapiro M.S. Homomeric and heteromeric assembly of KCNQ (Kv7) K+ channels assayed by total internal reflection fluorescence/fluorescence resonance energy transfer and patch clamp analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:30668–30676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805216200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Axelrod D. Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy in cell biology. Methods Enzymol. 2003;361:1–33. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)61003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang Y., Lee A., MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature. 2003;423:33–41. doi: 10.1038/nature01580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Y., Morais-Cabral J.H., MacKinnon R. Chemistry of ion coordination and hydration revealed by a K+ channel-Fab complex at 2.0 A resolution. Nature. 2001;414:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35102009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yellen G., Sodickson D., Jurman M.E. An engineered cysteine in the external mouth of a K+ channel allows inactivation to be modulated by metal binding. Biophys. J. 1994;66:1068–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80888-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y., Jurman M.E., Yellen G. Dynamic rearrangement of the outer mouth of a K+ channel during gating. Neuron. 1996;16:859–867. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y., MacKinnon R. The occupancy of ions in the K+ selectivity filter: charge balance and coupling of ion binding to a protein conformational change underlie high conduction rates. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;333:965–975. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valiyaveetil F.I., Leonetti M., Mackinnon R. Ion selectivity in a semisynthetic K+ channel locked in the conductive conformation. Science. 2006;314:1004–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1133415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lockless S.W., Zhou M., MacKinnon R. Structural and thermodynamic properties of selective ion binding in a K+ channel. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng Y., Scarsdale J.N., Kellogg G.E. Hydropathic analysis and comparison of KcsA and Shaker potassium channels. Chem. Biodivers. 2007;4:2578–2592. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cordero-Morales J.F., Jogini V., Perozo E. A multipoint hydrogen-bond network underlying KcsA C-type inactivation. Biophys. J. 2011;100:2387–2393. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.