Abstract

We describe quantitatively the interactions in a mixture of a saturated and an unsaturated phospholipid, and their consequences to the phase behavior at macroscopic and microscopic levels. This type of lipid-lipid interaction is fundamental in determining the organization and physical behavior of biological membranes. Mixtures of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC) are examined in detail by multiple experimental approaches (differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), fluorescence resonance energy transfer, and confocal fluorescence microscopy) in combination with Monte Carlo simulations in a lattice. The interactions between all possible pairs of lipid species and states are determined by matching the heat capacity calculated through Monte Carlo simulations to that measured experimentally by DSC. Only for one other lipid system, a mixture between two saturated phosphatidylcholines, is a similar quantitative description available. The interactions in the two systems and different representations used to model them are compared. Phase separation occurs in DPPC/POPC at about the center of the phase diagram mapped by DSC, but not at all compositions and temperatures in the coexistence region. Close to the extremes of composition, the phase behavior is best described by large fluctuations. At the heat capacity maxima in the mixtures, the domain size distributions change remarkably; large domains disappear and cooperative fluctuations increase.

Introduction

Lipid-lipid interactions are fundamental in determining the organization and physical behavior of membranes (1). Establishing the magnitudes of those interactions and understanding the consequences of those magnitudes for lipid organization is therefore of primary biological importance. The binary system of distearoylphosphatidylcholine (DSPC) and dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (DMPC) is the only one for which lipid-lipid interactions have been obtained for the various possible pairs of states (gel, liquid crystalline) of the two lipids, through a rigorous combination of differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and Monte Carlo simulations (2–5). In eukaryotic membranes, however, ordered and disordered phospholipids correspond to saturated and unsaturated species, not to different saturated lipids with high (DSPC) and low (DMPC) melting temperatures (Tm).

Mixtures of saturated and unsaturated phospholipids have never been examined to the same degree, and a similar quantitative understanding is therefore lacking. We have tackled this problem using mixtures of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC). POPC is the most common unsaturated phosphatidylcholine (PC) in eukaryotic membranes. DPPC is a rare component of biological membranes, although it occurs in large amounts in lung surfactant (6). We have chosen it to model the saturated component in these mixtures because DPPC is the best characterized of all phospholipids. DPPC has been fundamental to our understanding of lipid bilayer phase transitions and the mixing behavior of ordered phospholipids with cholesterol (Chol). Understanding first a system of well-studied components will allow us to build an intuition and test models for mixtures that are more relevant for biological membranes, such as sphingomyelin/POPC/Chol. To that end, DPPC/Chol was recently modeled using solely pairwise lipid-lipid interactions, with realistic values derived from experiment (7). The advantage of determining how lipids interact with each other, instead of only constructing a phase diagram, is that knowing the interactions allows us to predict their behavior even in conditions that are not as accessible to physical experimentation, namely in the more complex lipid mixtures of cell membranes.

The phase diagram of DPPC/POPC (8) shows a large phase coexistence region of gel (g) and liquid crystalline phase (l). Very few studies of this system exist that are relevant to lipid-lipid interactions, but gel-liquid coexistence has been demonstrated in giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) (9). Here we examine the phase transition in DPPC/POPC mixtures using a combination of DSC, fluorescence (Förster) resonance energy transfer (FRET), confocal fluorescence microscopy of GUVs, and Monte Carlo simulations of a lattice model with lipid-lipid pairwise interactions.

In the simulations, each site in the lattice corresponds to one phospholipid molecule. A triangular lattice is used, which means that each site has z = 6 nearest neighbors. This is the same representation used for DPPC by Ivanova and Heimburg (10). Ehrig et al. (4,5) used a square lattice, where each site represents a phospholipid with z = 4 neighbors. Alternatively, the lattice sites can represent acyl chains, which better reflects the bilayer packing in the gel. The enthalpy of the transition is halved, meaning that the chains in the same phospholipid melt separately. In the liquid phase, however, neither representation is geometrically correct. Molecular dynamics simulations suggest that a lipid molecule has, on average, 4–6 neighbors (Personal communication, Dr. Hee-Seung Lee, University of North Carolina Wilmington, 2012). Jerala et al. (11) explicitly compared alternative representations in Monte Carlo simulations of DPPC small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs). They introduced a more realistic model where the sites of a triangular lattice are occupied by the acyl chains, which are infinitely coupled, physically and thermodynamically, in pairs; that is, the two acyl chains of a phospholipid melt concomitantly. The three models (whole lipids, chains, or dimers) provide equivalent descriptions of the excess heat capacity function (ΔCp(T)) in DPPC SUVs (11).

The Monte Carlo simulations provide a rigorous method to deconvolute the complex ΔCp(T) determined by DSC. The interactions obtained determine the lipid domain structure in terms of composition and lipid state, and allow us to understand the FRET results. The magnitude of the gel-liquid coexistence region in the phase diagram (8) suggested that true, macroscopic phase separation occurs in this system. Our results, however, demonstrate a more complex behavior.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-n-(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) (NBD-DOPE), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-n-lissamine rhodamine B (LRh-DOPE), and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-n-(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) (NBD-DPPE), in chloroform solution, were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Organic solvents (high-performance liquid chromatography, American Chemical Society grade) were from Burdick & Jackson (Muskegon, MI), and Triton X-100, from Acros (Morris Plains, NJ). Lipids and probes were tested by thin-layer chromatography and used without further purification.

Preparation of large unilamellar vesicles

Large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs), in buffer containing 20 mM MOPS, pH 7.5, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.02% NaN3, and 100 mM KCl, were prepared by extrusion, as previously described in Frazier et al. (12). The suspensions were extruded 10 times using an extruder (Lipex Biomembranes, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) through two stacked 0.1-μm-pore size Nucleopore polycarbonate filters (Whatman, Florham, NJ), at 50°C (room temperature for pure POPC). Lipid concentrations were assayed by a modified Bartlett phosphate method (13,14).

Preparation of giant unilamellar vesicles

Giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) of DPPC/POPC with 0.1 mol % LRh-PE were prepared by electroformation (15). A 5-μL aliquot of a lipid solution in chloroform (1 mg/mL) was applied onto silver and platinum wire electrodes (1.0 mm diameter), which were later immersed in a plastic chamber containing ∼300 μL 0.1 M sucrose solution and connected to a function generator (Global Specialties, New Haven, CT). Electroformation was performed in a water bath at ∼50°C, 2.4 V, 10 Hz for 2 h, then at 2 Hz for 30 min, and slowly cooled to room temperature. The samples for microscopy were prepared by adding 10 μL of GUV suspension to a culture dish coated with bovine serum albumin (fatty-acid free; ICN, Aurora, OH), containing 240 μL of 0.1 M glucose solution. The lipid aliquot was placed in an area bound by o-ring sealed with silicone high vacuum grease (Dow Corning, Midland, MI).

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer

FRET (16) was measured between NBD-DOPE (donor) and LRh-DOPE (acceptor) incorporated at 0.4 mol % in the lipid vesicles. The characteristic Förster distance for this pair is ∼52–60 Å (17–19), assuming random orientation of the fluorophores (parameter κ2 = 2/3) (16). The fluorescence measurements were performed in LUVs, 40 μM in total lipid, in an SLM Aminco 8100 spectrofluorometer upgraded by ISS (Champaign, IL). Fluorescence emission scans were recorded upon excitation of NBD at 463 nm (slit widths of 2 and 8 nm, for excitation and emission). FRET was measured from 14°C to 46°C, in pure POPC and DPPC/POPC vesicles. The temperature in the cuvette was monitored to within 0.1°C, with a thermistor. Vesicles containing only NBD-DOPE emit with a maximum at 530 nm (Fig. 1 A, solid line). When LRh-DOPE is also incorporated in the membrane, the NBD fluorescence decreases and LRh-DOPE emission is observed, with a maximum at 590 nm (Fig. 1 A, dashed line).

Figure 1.

(A) Spectra in POPC LUVs containing only donor, NBD-DOPE (solid line), or donor and acceptor, LRh-DOPE (dashed). (B) Calibration curve of the energy transfer efficiency (Et) to the emission peak ratio of LRh (590 nm) to NBD (530 nm) in POPC with different concentrations of probes. (Circles) LRh-DOPE/NBD-DOPE (solid) or NBD-DPPE (open) in vesicles with and without acceptors. (Triangles) Vesicles with LRh-DOPE/NBD-DOPE before and after addition of Triton X-100. The line is a fit of the equation, Et = 0.839 [1 – exp(−0.442x)] to all data, where x is the peak ratio (LRh/NBD).

The energy transfer efficiency is calculated from the ratio of fluorescence intensities of the donor emission in the presence (FDA) and absence (FD) of acceptor, Et = 1 – FDA/FD. Here, Et was determined using a procedure previously developed that allows the use of a single sample, if the relation between Et and the ratio of acceptor/donor peak intensities is known (12). To this end, a calibration curve was constructed (Fig. 1 B), using a very large number of POPC samples, where donor and acceptor concentrations were varied, employing two methods. In the first, Et was determined in two identical LUV samples, one containing only donor, and the other, donor and acceptor. In a single determination, the error in Et is significant because of slight variations in probe concentrations in the vesicles. In the second method, the spectrum was recorded on vesicles with both probes incorporated, and then the detergent Triton X-100 was added, to a final concentration of 2% (v/v) (17,20). The donor and the acceptor become dispersed in separate detergent micelles and energy transfer stops. The fluorescence intensities were corrected for dilution and change in quantum yield of the donor (NBD) in the presence of Triton X-100. Thus, the ratio of emission intensities of LRh at 590 nm to NBD at 530 nm was mapped onto Et (Fig. 1 B). Finally, in DPPC/POPC mixed vesicles containing both LRh-DOPE and NBD-DOPE, Et was determined directly from the peak ratio in the emission spectrum, in a single experiment, using this calibration curve.

Differential scanning calorimetry

The heat capacity of LUV suspensions in buffer (degassed under vacuum of 500 mm Hg for 10 min) was measured using a high sensitivity Nano DSC (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE), equipped with 300-μL twin gold capillary cells, under a slight pressure (set once to 3 atm). The scan rate was 0.1°C/min for pure lipids and 0.2°C/min for mixtures. The DSC curves were corrected by baseline subtraction as previously described in Pokorny et al. (21).

Confocal fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy of GUVs was performed with a Fluoview FV1000 scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY), using He-Ne laser excitation at 543 nm, reflected by a dichroic mirror (DM405/488/543). The confocal aperture size was 80 μm. The image was optimized by scanning in XY mode while adjusting laser transmissivity and PMT voltage. Then, in XYZ mode, Z-scans were performed with 0.5- or 1-μm-step-size increments. Three-dimensional reconstruction of images was done using Fluoview software (Olympus) and edited using the GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP, http://www.gimp.org/).

Monte Carlo simulations

Simulations were performed as previously described (7,12,22) using standard Monte Carlo methods (23–25). The lipid membrane was represented by a triangular lattice with skew-periodic boundary conditions. Each site on the lattice is occupied by one phospholipid. Two types of steps were executed to obtain equilibrium configurations. In a non-nearest-neighbor Kawasaki step (26), the lipids are exchanged by randomly selecting partners on the lattice. In a Glauber step (27), the lipid state is switched between gel and liquid. The choice between the two steps is aleatory. Acceptance or rejection of all attempted moves is based on the Metropolis criterion (28) with a move probability that depends exponentially on the free energy change (7,23,24), using a random number (29) for the decision. Most simulations were performed in 100 × 100 lattices; they included a preequilibration period of 1–5 × 104 Monte Carlo cycles followed by a period of 1–2 × 106 acquisition cycles, which were more than sufficient to obtain equilibrium properties, as judged by the evolution of the excess heat capacity (ΔCp). Simulations in lattices of 200 × 200 and 300 × 300 sites yielded equivalent results, and shorter runs were sufficient to obtain equilibrium properties. Six lipid-lipid interaction parameters (ω) were used, involving two possible states, gel (g) or liquid (l), for each lipid species, DPPC (component A) or POPC (component B). The lipid-lipid interaction parameters between unlike, A-B nearest-neighbors are defined by

| (1) |

where the ϵij values represent the contact (nearest-neighbor) interactions between lipids i and j, which can be any combination of the two species and two states. The excess heat capacity in the simulations is obtained from the enthalpy fluctuations (30),

| (2) |

Results

Fluorescence energy transfer

Fluorescence (Förster) resonance energy transfer (FRET) between NBD-DOPE (donor) and LRh-DOPE (acceptor), two headgroup-labeled lipid probes that partition almost exclusively into liquid-disordered phases (18,31), was measured in pure POPC and in mixtures of DPPC/POPC, as a function of temperature. The FRET efficiency (Et) obtained is shown in the left panels of Fig. 2 for POPC (squares) and DPPC/POPC 25:75 (A), 50:50 (B), and 75:25 (C) (solid circles). In the mixtures, Et deviates from the values observed in the homogeneous POPC membrane by amounts that increase with decreasing temperature and with increasing DPPC content. Qualitatively, this is a consequence of lipid domain formation and probe exclusion from the gel. To interpret the results quantitatively, we turned to Monte Carlo simulations.

Figure 2.

Energy transfer efficiency (Et) between NBD-DoPE and LRh-DoPE in DPPC/POPC mixtures as a function of temperature. (Left) Experimental data: (solid circles) DPPC/ POPC 25:75 (A), 50:50 (B), and 75:25 (C). (Squares) Pure POPC. The samples contain 0.4 mol % of each probe. Averages and standard deviations of three independent samples (four in pure POPC, error bars omitted for clarity) are shown. (Right) Monte Carlo simulations (open circles) superimposed on the same experimental data (solid circles) shown (corresponding left panels), after subtracting a baseline for pure POPC in both the experimental and simulation data, for the mixtures DPPC/POPC 25:75 (D), 50:50 (E), and 75:25 (F). The slight difference between the abscissas of the experimental data in pure POPC and the mixtures observed at high temperatures (left) was also subtracted. Those slight differences at high temperatures are due only to experimental uncertainty.

Monte Carlo simulations of energy transfer

Monte Carlo simulations were performed to obtain the equilibrium properties of the membrane, represented as a lattice, where each site corresponds to a lipid (DPPC or POPC), in the gel or liquid states. The distribution of lipids on the lattice depends on nearest-neighbor interaction parameters (Eq. 1), which were determined from thermodynamics as described below. To calculate energy transfer, 0.8% of POPC was replaced by probes, which were assumed to behave like POPC in all other respects. Then, FRET was simulated, as previously described in Frazier et al. (12), in the same DPPC/POPC mixtures examined experimentally, as a function of temperature. The Förster distance for the NBD-DOPE/LRh-DOPE pair is R0 = 52–60 Å (17–19). The mean value, R0 = 56 Å, corresponds to seven lipids with a lipid diameter of 8 Å. The calculation of Et assumes that energy transfer is complete if an acceptor is found within a distance R = 7 lipids from a donor, but drops to zero otherwise. This corresponds to a step-function approximation to R6/(R6 + R60), which we used previously with very good results (12). The temperature dependence of Et that arises experimentally (even in pure POPC) solely from the effect of temperature on the fluorescence emission of the probes and on the energy transfer itself (including bilayer expansion) is, of course, absent from the simulations.

To better compare simulations and experiments, in the right panels of Fig. 2, Et in pure POPC was subtracted from that in the mixtures of DPPC/POPC 25:75 (D), 50:50 (E), and 75:25 (F). Solid circles correspond to experiment and open circles, to simulation. The experimental temperature dependence that does not arise from probe partitioning and domain formation is thus factored out. Only differences are shown in Fig. 2, but the range of calculated Et (0.49–0.59) is similar to that observed experimentally (Fig. 2, left). At high temperatures, the whole membrane is in the liquid phase; Et is low because the probes are uniformly distributed, diluted in the host lipid. As the temperature decreases and gel forms, Et increases. The phase transition, which is observed by the deviation of the data from the horizontal line, occurs essentially over the same temperatures in the experiments and simulations. At still lower temperatures, a maximum is reached in the simulations, especially noticeable in DPPC/POPC 75:25 (Fig. 2 F), which corresponds to the maximum segregation of the fluorophores in small liquid domains. As the whole membrane enters the gel phase, the calculated Et drops down to the level of pure POPC, because the probes are again uniformly distributed, this time in the gel. The difference in experiment and simulation at low temperatures probably arises because the probes are derivatives of DOPE, which may show some demixing from POPC in the gel phase. Note that DOPE and DOPC only freeze at –16°C and –18°C (32). Simulating the probes as POPC always in the liquid state, however, resulted in much worse agreement in the transition region (not shown).

Differential scanning calorimetry

The excess heat capacity functions, ΔCp(T), obtained by DSC are shown by the lines in Fig. 3 for LUVs of pure DPPC (A) and POPC (B). In DPPC, the small sharp peak on the high temperature side of the solid line arises from remnant multilamellar vesicles (MLVs). (This peak is much larger if vesicles are only extruded 10 times; the data shown were acquired in LUVs extruded 40 times.) The dashed line in Fig. 3 A shows data in LUVs prepared by fusion of SUVs from Ivanova and Heimburg (10).

Figure 3.

(Top) Excess heat capacity of DPPC (A) and POPC (B) LUVs, obtained by DSC (lines) and calculated from Monte Carlo simulations (circles), with the parameters in Table 1. (A) (Solid line) Our data on DPPC LUVs. (The small sharp peak on the right side arises from remnant MLVs.) (Dashed line) From Ivanova and Heimburg (10), courtesy of Dr. Heimburg, slightly shifted to the same Tm and ΔCpmax for easier comparison (original ΔCpmax = 3.1 kcal/mol/K (10)). (B) POPC curve obtained in the presence of 30% ethylene glycol, shifted (from –5.5°C) to the Tm of POPC in water, –4°C in LUVs. (Bottom) Snapshots of simulations of DPPC (C) and POPC (D) at Tm, in 200 × 200 lattices. White is gel and black is liquid.

The transition enthalpy change, ΔH = 8.7 kcal/mol in DPPC MLVs (32–34), does not vary much with vesicle type (10,11,24). A decrease in ΔH from MLVs to LUVs to SUVs has been reported (35), but is probably due to larger error in integration as ΔCp broadens in smaller vesicles. The Tm and the excess heat capacity maximum (ΔCpmax) depend slightly on vesicle type. In MLVs, Tm = 41.5°C (32,33,35) and ΔCpmax ≈ 10–70 kcal/K/mol (7,10,33,34). In SUVs, Tm = 37.2°C (11,24,35,36) and ΔCpmax = 2.0 kcal/K/mol (11,24). In DPPC LUVs, we found Tm = 40.8°C and ΔCpmax = 3.6 ± 0.4 kcal/K/mol, consistent with Tm = 41.3°C and ΔCpmax = 3.1 kcal/K/mol (10). We also found ΔH = 7.0 ± 0.5 kcal/mol, consistent with 7.5 kcal/mol (36). These values are not significantly different from the consensus ΔH = 8.7 kcal/mol, within the variation in the literature (35).

In POPC, Tm = –3°C in MLVs (32,35), varying from –2 to –5°C in the literature (8,37–44). Because our calorimeter cannot access water-freezing conditions, the heat capacity of POPC was measured in buffers containing ethylene glycol (EG). Assuming that EG causes freezing-point depression in POPC to a similar degree as in DPPC, which is ≈ –1°C at 20–30% (v/v) EG (45), we estimate that Tm = –4°C in POPC LUVs in the absence of EG. Values for the transition enthalpy in POPC MLVs of ΔH = 4.7–8.1 kcal/mol have been reported (8,35,37–44). Excluding the older values, which are the largest, the mean is 5.0–6.0 kcal/mol. In the presence of 30% EG, we obtained ΔH = 4.0–5.2 kcal/mol (in LUVs and MLVs), which are not significantly different from the standard ΔH = 5.8 kcal/mol (35).

Fig. 4 shows ΔCp(T) for DPPC/POPC 25:75 (A), 50:50 (B), and 75:25 (D), obtained by DSC (lines) in LUV suspensions. The onset and completion temperatures estimated from the DSC scans are plotted in the phase diagram (see Fig. 7) and coincide with those of Curatolo et al. (8). To deconvolute the ΔCp(T) of these mixtures and extract lipid-lipid interactions, we turned again to Monte Carlo simulations in a lattice.

Figure 4.

Excess heat capacity in LUVs of DPPC/POPC 25:75 (A), 50:50 (B), and 75:25 (C). (Lines) Experimental (DSC). (Circles) Monte Carlo calculations, with the parameters in Table 1.

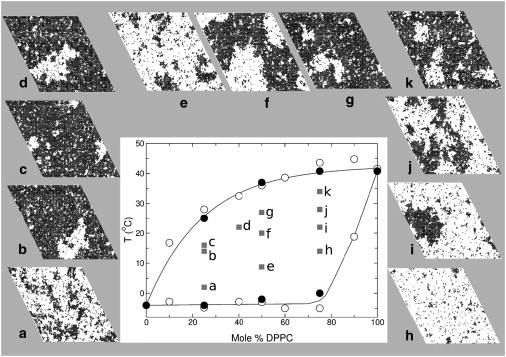

Figure 7.

(Center) Phase diagram of DPPC/POPC. The onset and completion temperatures estimated from DSC curves are indicated (open circles, from Curatolo et al. (8), and solid circles, our data). (Lines) Our best estimate of the phase boundaries. (Periphery) Snapshots of Monte Carlo simulations (100 × 100 lattices, where white is gel and black is liquid) at the compositions and temperatures indicated (corresponding letter-labeled squares in the phase diagram).

Monte Carlo simulations of the excess heat capacity

The simulations use an Ising model (46,47) under a field ΔG° = ΔH° − TΔS° for each lipid species, where ΔH° is the enthalpy change and ΔS° = ΔH°/Tm is the conformational entropy change associated with the increase in gauche conformers when the lipid chains melt (10). The field is zero at Tm. The Monte Carlo simulations use as inputs the experimental values of ΔH and Tm of the gel-liquid crystalline phase transition of the pure lipids and the lipid-lipid, unlike nearest-neighbor interaction parameters, ω (Eq. 1). In classical magnetic systems (spins), the interaction parameter is designated by J, which is related to ω by J = ω/2 (48).

The values of ω in DPPC/POPC are not known experimentally. However, based on nearest-neighbor-recognition (NNR) experiments on closely related systems (49–52), we had a good idea of their probable range (1). In the liquid (l) phase, in DMPC/POPC, = 30 cal/mol; in DPPC/DOPC and DSPC/POPC, = 70 cal/mol; and in DSPC/DOPC, = 110 cal/mol (1). This suggests that in DPPC/POPC, in the liquid phase, ≈ 50 cal/mol. The DSPC/DMPC system, which exhibits a similar degree of nonideal mixing, also provided initial guidance in the choice of interaction parameters (2–4). In the end, the ω-values were varied until ΔCp(T) calculated from Monte Carlo simulations matched that obtained experimentally by DSC. The complete set of parameters used is listed in Table 1. Note that when ωgl and ωlg refer to two different lipids, the first state (g or l) in the superscript refers to component A, which is always the lipid with higher Tm (DPPC or DSPC), and the second state, to component B, the lipid with lower Tm (POPC or DMPC).

Table 1.

Lipid-lipid interaction parameters, transition enthalpies, and melting temperatures used in Monte Carlo simulations

| Lipids |

ω (cal/mol) |

ΔH (kcal/mol) | Tm (K) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ωgl | ωlg | ωgg | ωll | |||

| DPPC (A) | 300 | 8.7 | 313.9 | |||

| POPC (B) | 240 | 5.8 | 269.15 | |||

| DPPC/POPC∗ | 450 | 240 | 140 | 70 | ||

| DSPC (A)† | 352 | 12‡ | 327.9 | |||

| DMPC (B) | 323 | 6.3 | 297.1 | |||

| DSPC/DMPC§ | 410 | 370 | 140 | 70 | ||

| DSPC/DMPC¶ | 480 | 510 | 220 | 70 | ||

When ωgl and ωlg refer to two different lipids, the first state (g or l) in the superscript refers to lipid A (DPPC or DSPC), and the second state, to lipid B (POPC or DMPC).

The ωgl values for pure DSPC and DMPC are exactly the same in the literature (2,3,5), if those from Ehrig et al. (5) are scaled by a factor of 4/6, the ratio of coordination numbers in the square and triangular lattices. Note, however, that these are interactions per acyl chain in a triangular lattice in the literature (2,3) but per lipid molecule in a square lattice in Ehrig et al. (5), scaled here by 4/6.

ΔH and Tm for DSPC and DMPC MLVs from Hac et al. (3).

Values from Hac et al. (3) and Sugár et al. (2), for interactions per acyl chain. Both studies use the same value for the g/l and the l/g interactions. They use very similar values for the g/g and l/l interactions, the averages of which are shown.

Values from Ehrig et al. (5), reported for interactions per lipid molecule in a square lattice, scaled by 4/6 to make them comparable to those in a triangular lattice (rounded to the nearest multiple of 10).

The values for the gel (g)-liquid (l) interactions in pure DPPC and POPC were determined first and kept fixed as the remaining ωAB values, pertaining to interactions in the mixtures, were optimized. The best value for DPPC was = 300 cal/mol, which is the same used by Ivanova and Heimburg (10), and for POPC, = 240 cal/mol. The calculated ΔCp values are shown by the solid circles in Fig. 3 for DPPC (A) and POPC (B), superimposed on the experimental DSC curves. The Monte Carlo calculations yielded ΔCpmax = 3.4 kcal/mol/K for DPPC and 1.1 kcal/mol/K for POPC in lattices of 100 × 100 to 300 × 300 sites. The latter corresponds to the size of a LUV. Neither DPPC nor POPC exhibit first-order phase transitions in LUVs. At ΔCpmax, large fluctuations in cluster sizes occur (Fig. 3, C and D) as previously shown for DPPC (10).

In DPPC/POPC mixtures, the Monte Carlo calculations yielded the ΔCp shown in Fig. 4 (circles) superimposed on the experimental DSC curves for DPPC/POPC 25:75 (A), 50:50 (B), and 75:25 (C). There is good agreement between the two. These simulations were performed in 100 × 100 lattices, but the results are equivalent in 200 × 200 and 300 × 300 lattices. (Compare, for example, the snapshots of DPPC/POPC 40:60 in Figs. 6 B and 7 d, later in the article.).

Figure 6.

(A) Example of GUVs of DPPC/POPC 40:60 at room temperature (∼22°C). The colors were inverted to match those in the snapshots of Monte Carlo simulations. In the picture shown, the dark areas are fluorescent (liquid phase) and the light areas are not (gel phase). Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Snapshot of DPPC/POPC 40:60 at 22°C, in a 200 × 200 lattice, showing the lipid states: (white) gel (of either lipid) and (black) liquid. (C) Same simulation as in panel B, but showing lipid species: (white) DPPC (in either state) and (black) POPC.

Small variations in any ωAB (∼±20 cal/mol) produce little change in ΔCp(T) in the mixtures. The temperatures of ΔCpmax in DPPC/POPC mixtures are most influenced by the interactions between the like states of the different lipids. Increasing destabilizes gel phases and lowers the temperatures of ΔCpmax associated with melting of DPPC- and POPC-rich gels. Conversely, increasing destabilizes the liquid phases and increases the temperatures of the ΔCpmax. The parameter has the least influence on ΔCp(T) because it corresponds to the rare contact between liquid DPPC (A) and gel POPC (B). The interaction between gel DPPC and liquid POPC is more important. Increasing sharpens the peaks in ΔCp(T), especially for the melting of DPPC-rich domains, but has a modest influence on their positions. Now, at a fixed temperature, a small change in an ωAB can have a large effect on domain sizes. For example, decreasing from 450 to 430 cal/mol at 22°C yields very similar ΔCp(T), but the gel domain size, defined by the number of gel lipids in a continuous cluster, changes dramatically, from a well-defined value to a broad distribution (Fig. 5, A and B, solid lines). This effect of slightly decreasing , however, is not fundamental; it can be reversed by lowering the temperature by 1–2°C (Fig. 5 B).

Figure 5.

Distribution functions of the gel domain sizes, defined by the number of gel-state lipids in a continuous cluster, in DPPC/POPC 40:60 around room temperature. (A) Using the best parameters (Table 1), including = 450 cal/mol. (B) Same, except = 430 cal/mol.

Because between 430 and 450 cal/mol produce very similar ΔCp(T) but very different domain sizes at a given temperature, we used fluorescence microscopy of GUVs to narrow the choice. GUVs of DPPC/POPC 40:60 at 22°C clearly show phase separation (Fig. 6 A), indicating that = 450 cal/mol is more correct. Fluorescence microscopy as a means to assess phase separation may suffer from complications due to lipid oxidation under high illumination (53), so that observed macroscopic phase separation may result from light-induced coalescence of small domains (54). However, our GUV fluorescence data were obtained with very low probe concentrations (0.1 mol %). These results, in combination with those of Shoemaker and Vanderlick (9), strongly suggest that large gel domains form in DPPC/POPC 40:60 at room temperature. The shapes of the gel domains observed in GUVs are similar to those seen in the snapshots of Monte Carlo simulations (Fig. 6, A and B). The gel is enriched in DPPC and the liquid, in POPC, but a considerable degree of mixing exists. This is illustrated in panels B and C of Fig. 6, which show lipid states (B) and species (C).

Discussion

We have obtained good estimates of lipid-lipid interactions (ω) in DPPC/POPC LUVs (Table 1) by a combination of experiment and Monte Carlo simulations in a triangular lattice, where each site represents a lipid. The ω are similar to those in DSPC/DMPC MLVs (2–5) despite the different lipids. The values obtained for DSPC/DMPC by Sugár et al. (2) and Hac et al. (3) in a triangular lattice (each site has z = 6 neighbors) are also shown in Table 1, together with those from Ehrig et al. (5) in a square lattice (z = 4) scaled by 4/6. (In two different lattices, with coordination numbers z and z′, ω scales approximately as zω ≈ z′ω′, because a smaller z needs to be compensated by a larger ω to achieve the same physical effect.) The similarity of the parameters is evident.

It should be noted that Sugár et al. (2) and Hac et al. (3) represented phospholipids as dimers of physically coupled chains, each lattice site corresponding to one acyl chain (11), but assumed that the two chains of the same phospholipid can melt separately. In pure systems, this is equivalent to treating sites as totally uncoupled chains; however, in mixtures it is not, because the mixing entropy is different (2). Nevertheless, the interaction parameters are comparable to those obtained with independent chains, and almost double those obtained with thermodynamically infinitely coupled chains (11). In fact, the ω-values are actually larger if sites represent chains rather than whole lipids, because with a halved ΔH (per chain) must increase to compensate for the smaller contribution of the melting of each site to ΔCp at ∼Tm. Thus, it would be incorrect to convert the values of per chain to those for whole lipids by multiplying by 2, which would yield ∼ 600 cal/mol-lipid for the gel-liquid interaction.

Treating lattice sites as physically coupled chains, however, introduces unnecessary complications and assumptions. If anything, these ωAB differ more from the experimental estimates obtained by nearest-neighbor recognition (NNR) experiments, which are independent of any lattice interpretation of the membrane. The NNR values in the liquid phase cited above, and also ωAB = 130 cal/mol for DSPC/DLPC in the liquid-ordered phase (1), which should approximate a gel-gel interaction, are remarkably close to those used here for whole phospholipids. This suggests that the error involved in approximating the geometry of the membrane is less serious than assuming that the two acyl chains can melt separately. Thus, we prefer the simpler representation used here. These issues notwithstanding, the simulations of the heat capacity are equivalent (5,11), and our ωAB values in DPPC/POPC are roughly similar to those of corresponding pairs in DSPC/DMPC (Table 1).

We now discuss the heat capacity and phase behavior of DPPC/POPC in light of the lipid-lipid interactions (Figs. 4 and 7). No true phase separation occurs in DPPC/POPC 25:75 at low temperature, but only a broad distribution of liquid domains (Figs. 7 a and 8 A). This is because the gel has a high content of POPC, whose interaction with the liquid states is not too unfavorable ( = 240 cal/mol). Note that the lipid with higher Tm is designated by A, and that with lower Tm, by B. Close to ΔCpmax at 2°C (Fig. 4 A), DPPC/POPC 25:75 looks similar to pure POPC (Figs. 3 D and 7 a). As the temperature increases, the gel becomes enriched in DPPC, which interacts repulsively with liquid POPC ( cal/mol). Phase separation occurs at 14°C, with formation of gel domains of a well-defined size (Figs. 7 b and 8 B). Close to ΔCpmax at 16°C (Fig. 4 A), the domains are small but still well defined (Figs. 7 c and 8 B). The main difference in DSPC/DMPC is that is much larger, because the DMPC gel interacts more repulsively with liquid states than the POPC gel (Table 1), which leads to macroscopic phase separation at low DSPC content (5).

Figure 8.

Distribution functions of domain sizes (number of lipids in a continuous cluster) of the minor phase in (A and B) DPPC/POPC 25:75, (C and D) DPPC/POPC 50:50, and (E and F) DPPC/POPC 75:25, at temperatures close to local ΔCpmax in each composition. (Left panels) Liquid; (right panels) gel.

The situation is different at the DPPC-rich end of the phase diagram, more like that observed in DSPC/DMPC (5). In DPPC/POPC 75:25, when liquid domains first form, they have a well-defined size (Figs. 7 i and 8 E). This is because the gel consists mainly of DPPC, which interacts repulsively with both liquid states, especially with POPC, the main component of the liquid. As the temperature is raised, more liquid forms, but by 32°C the domains are no longer compact (Fig. 7 j). The distributions appear to indicate that gel domains have a well-defined size (Fig. 8 F), but this is misleading. These gel domains are very large because the system is near the percolation point of the lattice (50%). In all the other cases of well-defined domain sizes discussed, the minor phase corresponds at most to 20–30%. When ΔCpmax is reached at 34°C (Fig. 4 C), the domain distribution is actually broad (Figs. 7 k and 8 F), suggesting critical fluctuations, as in DSPC/DMPC (5).

In the middle of the phase diagram, close to DPPC/POPC 50:50, macroscopic phase separation exists. At the low peak in ΔCp at 8°C (Fig. 4 B), large liquid domains begin to form (Figs. 7 e and 8 C). Beyond that temperature, phase separation occurs (Fig. 7, d and f) because, given the large difference in Tm between POPC (–4°C) and DPPC (40.8°C), the gel is composed mainly of DPPC and the liquid, of POPC, and the interaction between those two states is the most repulsive in the system ( = 450 cal/mol). When ΔCpmax in DPPC/POPC 50:50 is reached at 27°C (Fig. 4 B), phase separation gives rise to a broad distribution of domains (Figs. 7 g and 8 D).

In conclusion, the maxima of ΔCp in mixtures of all compositions occur at temperatures where the distributions of domain sizes change remarkably. The large domains disappear, and cooperative fluctuations increase. Phase separation occurs at about the center of the phase diagram mapped by DSC, but not at all compositions and temperatures in the coexistence region. Close to the two extremes of composition, the phase behavior is best described by fluctuations. This complex behavior follows naturally from the lipid-lipid interactions, which were determined by requiring agreement between Monte Carlo simulations and experiments (DSC, FRET, confocal fluorescence microscopy). Ultimately, understanding how lipids interact is more important than describing their phase behavior because knowing these interactions enables us to predict lipid behavior in conditions that are not amenable to the types of physical experiments performed here, namely in biological membranes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Richard Dillaman and Mark Gay for the use and expert help with the confocal fluorescence microscope, and Breanna Villars for help with DSC experiments.

This work was supported by Research Corporation Cottrel College Science Award 7622 and by North Carolina Biotechnology Center grant 2009-IDG-1031. Grant DBI 0420948 from the National Science Foundation is acknowledged for the support of the confocal fluorescence microscope.

References

- 1.Almeida P.F.F. Thermodynamics of lipid interactions in complex bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugár I.P., Thompson T.E., Biltonen R.L. Monte Carlo simulation of two-component bilayers: DMPC/DSPC mixtures. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2099–2110. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77366-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hac A.E., Seeger H.M., Heimburg T. Diffusion in two-component lipid membranes—a fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and Monte Carlo simulation study. Biophys. J. 2005;88:317–333. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrig J., Petrov E.P., Schwille P. Near-critical fluctuations and cytoskeleton-assisted phase separation lead to subdiffusion in cell membranes. Biophys. J. 2011;100:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrig J., Petrov E.P., Schwille P. Phase separation and near-critical fluctuations in two-component lipid membranes: Monte Carlo simulations on experimentally relevant scales. New J. Phys. 2011;13:045019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Possmayer F., Yu S.H., Harding P.G. Pulmonary surfactant. Can. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1984;62:1121–1133. doi: 10.1139/o84-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almeida P.F. A simple thermodynamic model of the liquid-ordered state and the interactions between phospholipids and cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2011;100:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.12.3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curatolo W., Sears B., Neuringer L.J. A calorimetry and deuterium NMR study of mixed model membranes of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleylphosphatidylcholine and saturated phosphatidylcholines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;817:261–270. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(85)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shoemaker S.D., Vanderlick T.K. Material studies of lipid vesicles in the L(α) and L(α)-gel coexistence regimes. Biophys. J. 2003;84:998–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74916-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanova V.P., Heimburg T. Histogram method to obtain heat capacities in lipid monolayers, curved bilayers, and membranes containing peptides. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2001;63:041914. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.63.041914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jerala R., Almeida P.F.F., Biltonen R.L. Simulation of the gel-fluid transition in a membrane composed of lipids with two connected acyl chains: application of a dimer-move step. Biophys. J. 1996;71:609–615. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79261-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frazier M.L., Wright J.R., Almeida P.F. Investigation of domain formation in sphingomyelin/cholesterol/POPC mixtures by fluorescence resonance energy transfer and Monte Carlo simulations. Biophys. J. 2007;92:2422–2433. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.100107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartlett G.R. Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 1959;234:466–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pokorny A., Birkbeck T.H., Almeida P.F. Mechanism and kinetics of δ-lysin interaction with phospholipid vesicles. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11044–11056. doi: 10.1021/bi020244r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angelova M.I., Soléau S., Bothorel P. Preparation of giant vesicles by external AC electric fields. Kinetics and applications. Prog. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1992;89:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lakowicz J.R. 3rd ed. Springer; New York: 2006. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolf D.E., Winiski A.P., Pagano R.E. Determination of the transbilayer distribution of fluorescent lipid analogues by nonradiative fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Biochemistry. 1992;31:2865–2873. doi: 10.1021/bi00126a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crane J.M., Tamm L.K. Role of cholesterol in the formation and nature of lipid rafts in planar and spherical model membranes. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2965–2979. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74347-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malinin V.S., Haque M.E., Lentz B.R. The rate of lipid transfer during fusion depends on the structure of fluorescent lipid probes: a new chain-labeled lipid transfer probe pair. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8292–8299. doi: 10.1021/bi010570r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Struck D.K., Hoekstra D., Pagano R.E. Use of resonance energy transfer to monitor membrane fusion. Biochemistry. 1981;20:4093–4099. doi: 10.1021/bi00517a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pokorny A., Yandek L.E., Almeida P.F. Temperature and composition dependence of the interaction of δ-lysin with ternary mixtures of sphingomyelin/cholesterol/POPC. Biophys. J. 2006;91:2184–2197. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.085027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almeida P.F., Best A., Hinderliter A. Monte Carlo simulation of protein-induced lipid demixing in a membrane with interactions derived from experiment. Biophys. J. 2011;101:1930–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heimburg T. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2007. Thermal Biophysics of Membranes. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugár I.P., Biltonen R.L., Mitchard N. Monte Carlo simulations of membranes: phase transition of small unilamellar dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine vesicles. Methods Enzymol. 1994;240:569–593. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)40064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Binder K., Heermann D.W. 3rd ed. Springer; New York: 1997. Monte Carlo Simulation in Statistical Physics. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawasaki K. Kinetics of Ising models. In: Domb C., Green M.S., editors. Vol. 2. Academic Press; New York: 1972. pp. 443–501. (Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glauber R.J. Time-dependent statistics of the Ising model. J. Math. Phys. 1963;4:294–307. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metropolis N., Rosenbluth A.W., Teller E. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 1953;21:1087–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Press W.H., Teukolsky S.A., Flannery B.P. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1994. Numerical Recipes in FORTRAN: The Art of Scientific Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill T.L. Dover; Mineola, New York: 1960. An Introduction to Statistical Thermodynamics. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayuyan A.G., Cohen F.S. Raft composition at physiological temperature and pH in the absence of detergents. Biophys. J. 2008;94:2654–2666. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.118596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cevc G., editor. Phospholipids Handbook. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mabrey S., Sturtevant J.M. Investigation of phase transitions of lipids and lipid mixtures by sensitivity differential scanning calorimetry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1976;73:3862–3866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suurkuusk J., Lentz B.R., Thompson T.E. A calorimetric and fluorescent probe study of the gel-liquid crystalline phase transition in small, single-lamellar dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine vesicles. Biochemistry. 1976;15:1393–1401. doi: 10.1021/bi00652a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koynova R., Caffrey M. Phases and phase transitions of the phosphatidylcholines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1376:91–145. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(98)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biltonen R.L., Lichtenberg D. The use of differential scanning calorimetry as a tool to characterize liposome preparations. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1993;64:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Kruyff B., Demel R.A., Rosenthal A.F. The effect of the polar headgroup on the lipid-cholesterol interaction: a monolayer and differential scanning calorimetry study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1973;307:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis P.J., Coolbear K.P., Keough K.M.W. Differential scanning calorimetric studies of the thermotropic phase behavior of membranes composed of dipalmitoyllecithin and mixed-acid unsaturated lecithins. Can. J. Biochem. 1980;58:851–858. doi: 10.1139/o80-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis P.J., Fleming B.D., Keough K.M. Gel to liquid-crystalline transition temperatures of water dispersions of two pairs of positional isomers of unsaturated mixed-acid phosphatidylcholines. Biochemistry. 1981;20:3633–3636. doi: 10.1021/bi00515a051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santaren J.F., Rico M., Ribera A. Thermal and 13C-NMR study of the dynamic structure of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine and 1-oleyl-2-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine in aqueous dispersions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1982;687:231–237. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(82)90551-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curatolo W. The effects of ethylene glycol and dimethyl sulfoxide on cerebroside metastability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;817:134–138. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(85)90075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curatolo W. The interactions of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleylphosphatidylcholine and bovine brain cerebroside. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1986;861:373–376. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(86)90441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silvius J.R. Thermotropic phase transitions of pure lipids in model membranes and their modification by membrane proteins. In: Jost P.C., Griffith O.H., editors. Vol. 2. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1982. pp. 239–281. (Lipid-Protein Interactions). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marsh D. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1990. CRC Handbook of Phospholipid Bilayers. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamazaki M., Ohshika M., Asano T. Phase transitions of phospholipid vesicles under osmotic stress and in the presence of ethylene glycol. Biophys. Chem. 1992;43:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(92)80039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ising E. Contribution to the theory of ferromagnetism. Z. Phys. 1925;31:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baxter R.J. Dover; Mineola, New York: 1982. Exactly Solved Models in Statistical Mechanics. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill T.L. Dover; Mineola, New York: 1956. Statistical Mechanics: Principles and Selected Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dewa T., Vigmond S.J., Regen S.L. Lateral heterogeneity in fluid bilayers composed of saturated and unsaturated phospholipids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:3435–3440. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krisovitch S.M., Regen S.L. Nearest-neighbor recognition in phospholipid membranes: a molecular-level approach to the study of membrane suprastructure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:9828–9835. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davidson S.M.K., Regen S.L. Nearest-neighbor recognition in phospholipid membranes. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:1269–1280. doi: 10.1021/cr960381s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tokutake N., Jing B., Regen S.L. Detection of unusual lipid mixing in cholesterol-rich phospholipid bilayers: the long and the short of it. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8994–8995. doi: 10.1021/ja0359355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ayuyan A.G., Cohen F.S. Lipid peroxides promote large rafts: effects of excitation of probes in fluorescence microscopy and electrochemical reactions during vesicle formation. Biophys. J. 2006;91:2172–2183. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.087387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao J., Wu J., Feigenson G. Phase studies of model biomembranes: macroscopic coexistence of Lα+Lβ, with light-induced coexistence of Lα+Lo phases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:2777–2786. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]