Abstract

The Fanconi Anemia (FA) pathway consists of proteins involved in repairing DNA damage, including interstrand cross-links (ICLs). The pathway contains an upstream multiprotein core complex that mediates the monoubiquitylation of the FANCD2 and FANCI heterodimer, and a downstream pathway that converges with a larger network of proteins with roles in homologous recombination and other DNA repair pathways. Selective killing of cancer cells with an intact FA pathway but deficient in certain other DNA repair pathways is an emerging approach to tailored cancer therapy. Inhibiting the FA pathway becomes selectively lethal when certain repair genes are defective, such as the checkpoint kinase ATM. Inhibiting the FA pathway in ATM deficient cells can be achieved with small molecule inhibitors, suggesting that new cancer therapeutics could be developed by identifying FA pathway inhibitors to treat cancers that contain defects that are synthetic lethal with FA.

1. Introduction

Fanconi anemia is a rare genetic disease featuring characteristic developmental abnormalities, a progressive pancytopenia, genomic instability, and predisposition to cancer [1, 2]. The FA pathway contains a multiprotein core complex, including at least twelve proteins that are required for the monoubiquitylation of the FANCD2/FANCI protein complex and for other functions that are not well understood [3–6]. The core complex includes the Fanconi proteins FANCA, FANCB, FANCC, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG, FANCL, and FANCM. At least five additional proteins are associated with the FA core complex, including FAAP100, FAAP24, FAAP20, and the histone fold dimer MHF1/MHF2 [1, 4, 7–10]. The core complex proteins function together as an E3 ubiquitin ligase assembly to monoubiquitylate the heterodimeric FANCI/FANCD2 (ID) complex. The monoubiquitylation of FANCD2 is a surrogate marker for the function of the FA pathway [11]. USP1 and its binding partner UAF1 regulate the deubiquitination of FANCD2 [12]. The breast cancer susceptibility and Fanconi proteins FANCD1/BRCA2, the partner of BRCA2 (PALB2/FANCN), a helicase associated with BRCA1 (FANCJ/BACH1), and several newly identified components including FAN1, FANCO/RAD51C, and FANCP/SLX4 [13–17] participate in the pathway to respond to and repair DNA damage (for review, see [5]).

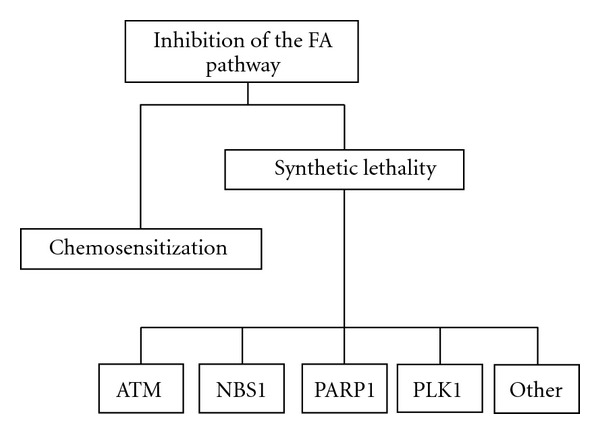

Although FA is rare, understanding the functional role of the FA proteins in context with other DNA damage response pathways will provide broader opportunities for new cancer therapeutics. Two general strategies could accomplish this, as illustrated in Figure 1: inhibiting the FA pathway in tumor cells to sensitize them to cross-linking agents, or by exploiting synthetic lethal relationships. The latter approach depends on inhibiting the FA pathway in tumor cells that are defective for a secondary pathway required for survival in the absence of the FA pathway.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of the FA pathway. Strategy for selectively targeting tumor cells by inhibition of the FA pathway by (a) chemosensitization to cross-linking agents or by (b) exploiting specific synthetic lethal interactions.

2. Chemosensitizing and Resensitizing Tumor Cells

A defining characteristic of FA cells is hypersensitivity to cross-linking agents, such as the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin [2, 5]. Cisplatin (and other platinum-based compounds) has been used as a chemotherapeutic drug for over 30 years (for review see [18]). The toxicity of platinum-based chemotherapy (nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and ototoxicity) and development of cisplatin resistance are limitations of the therapy [18–20]. Once inside the cell, cisplatin enters the nucleus and forms covalent DNA interstrand cross-links via platinum-DNA adducts. These cross-links block ongoing DNA replication, and in the absence of repair, activate apoptotic pathways [18, 19]. A functional FA pathway is required for processing damage after exposure to cisplatin and other crosslinking agents, and is at least partially responsible for resistance to cisplatin. Cell-free and cell-based assays have identified inhibitors of the FA pathway, and some of these inhibitors can resensitize platinum-resistant tumors and cell lines [19, 21, 22]. Further efforts to identify small molecule compounds that specifically inhibit the FA pathway could lead to improved resensitization from treatment-induced resistance.

3. Exploiting Synthetic Lethal Interactions

In addition to sensitization, inhibiting the FA pathway may be an effective strategy to exploit synthetic lethal interactions aimed at improving targeted killing of tumor cells. Current approaches in cancer treatment are generally not selective, affecting both cancer cells and normal cells. However, inactivation of DNA repair pathways, an event that occurs frequently during tumor development [23], can make cancer cells overdependent on a reduced set of DNA repair pathways for survival. There is new evidence that targeting the remaining functional pathways by using a synthetic lethal approach can be useful for single-agent and combination therapies in such tumors. Two genes have a synthetic lethal relationship if mutants for either gene are viable but simultaneous mutations are lethal [20]. A successful example of this approach is specific targeting of BRCA-deficient tumors with PARP (poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase) inhibitors [24].

4. Defects in Homologous Recombination and Sensitivity to PARP Inhibitors

Defects in HR repair can result in an overreliance on the protein PARP1, which is responsible for repair of DNA single strand breaks by the base excision repair pathway. Unrepaired single-strand breaks are converted to double-strand breaks during replication and must be repaired by HR [25–27]. Thus, treating cells that are defective in HR with PARP inhibitors results in a targeted killing of the defective cells, while cells with intact HR are capable of repair. Defects in breast cancer susceptibility proteins BRCA1 and BRCA2 (FANCD1) result in HR defects [28]. Clinical trials investigating the effectiveness of PARP inhibitors against recurrent ovarian cancer have been promising, but rigorous stratification of tumors for HR status or “BRCA-ness” (defects in HR) is needed to identify the patients who are likely to benefit [29–31]. Future clinical trials with PARP1 inhibitors in breast cancer may require combination therapies, evaluation of resistance, and identification of non-BRCA biomarkers [32].

PARP1 Inhibition has also been shown to be selectively toxic to ATM-defective tumor cell lines in vitro and to increase radiosensitivity of other ATM-proficient cell lines, including nonsmall-cell lung cancer, medulloblastoma, ependymoma, and high-grade gliomas [33–35]. In addition, cell lines lacking functional Mre11 are sensitive to PARP1 inhibitors, strengthening the case for combined use of PARP1 inhibitors with inhibitors of the FA pathway [36, 37].

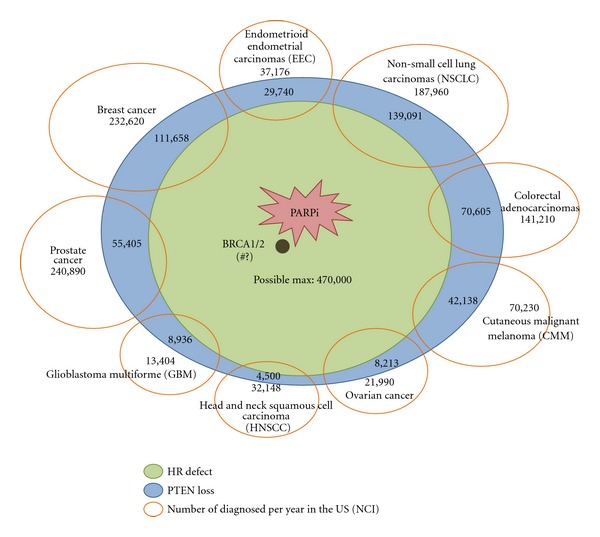

PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) is a tumor-suppressor gene and one of the most commonly mutated genes in human tumor cells [38, 39] (see Figure 2). PTEN deficiency results in decreased expression of RAD51, which is required for homologous recombination [38, 40]. PTEN deficient tumors are thus candidates for targeted therapy by PARP1 inhibition [36, 38]. Although approximately 470,000 (48%) of 977,628 newly diagnosed cancers each year in the US may have PTEN defects, only a subset of these cancers will have PTEN mutations that result in homologous recombination defects and sensitivity to PARP inhibitors [28, 39, 41–51]. Current studies are aimed at determining the relationship between PTEN loss, RAD51 expression, and PARP1 inhibitor sensitivity [36]. Efforts to asses HR status to establish which PTEN mutations lead to an HR defect, and determining under what circumstances RAD51 expression could be used as a biomarker, will be useful to stratify and predict PARP1 inhibitor sensitivity.

Figure 2.

PTEN defects in cancers. Types of cancer diagnosed annually in the US (orange oval), with the estimates for PTEN deficiencies shown in each type (blue oval). An unknown percentage of tumors with PTEN deficiencies will have a defect in homologous recombination (HR) repair, predicting sensitivity to treatment with PARP1 inhibitors (green oval).

Synthetic lethal interactions with the FA pathway have been explored. An siRNA-based screen of cells deficient in the Fanconi core complex protein, FANCG, showed that ATM, PARP1, NBS1, and PLK1 were among the genes with a synthetic lethal interaction [52] (see Table 1). The FA-ATM synthetic lethal relationship is particularly interesting since ATM deficiency has been reported in a subset of patients with hematological malignancies, including mantle cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia [53, 54], making these potential targets for treatment with FA pathway inhibitors (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Function and expression of genes synthetically lethal with FA.

| Gene synthetically lethal with FA genes | Function | Expression in tumor cells |

|---|---|---|

| TREX2 [52] | DNA exonuclease; SAGA complex pathway | Expressed in most tumor cell lines [60] |

| PARP1 [52] | BER | Overexpressed in tumors, including medulloblastoma, ependymoma, HGG, melanoma, and breast cancers [35, 61–63] |

| PLK1 [52] | Cell-cycle progression | Over-expressed in many human tumors [64] |

| RAD6/HR6B [52] | Switching of DNA polymerases | Upregulated in metastatic mammary tumors [65] |

| CDK7 [52] | Transcription | Moderately over-expressed in tumor cell lines [66] |

| TP53BP1 [52] | DSB sensing; ATM activation | Underexpressed in most cases of triple negative breast cancer [67] |

| ATM [52] | DSB response kinase | Under-expressed in some tumors, see Figure 3 |

| NEIL1 [52] | BER | Expression reduced in 46% of gastric cancers [68] |

| RAD54B [52] | HR | Known to be mutated in cancer cell lines [69, 70] |

| NBS1 [52] | DSB sensing; ATM activation | Over-expressed in HNSCC tumors [71] |

| ADH5 [6] | Formaldehyde processing | Reduced expression in melanoma cells [72] |

Table 2.

ATM-deficiency in cancer.

| Malignancy | ATM-deficient cell lines/number tested |

|---|---|

| T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia [73] | 17/32 |

| Mantle cell lymphoma [53] | 12/28 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma [74] | 7/17 |

| Chronic lymphoblastic leukemia [54, 73] | 16/50, 38/111 |

| BRCA1-negative breast cancer [75] | 12/36 |

| BRCA2 negative breast cancer [75] | 12/40 |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia [54] | 4/15 |

| Non-BRCA1/BRCA2 negative breast cancers [75] | 118/1106 |

| Other lymphomas [53] | 10/97 |

5. Inhibiting the FA Pathway

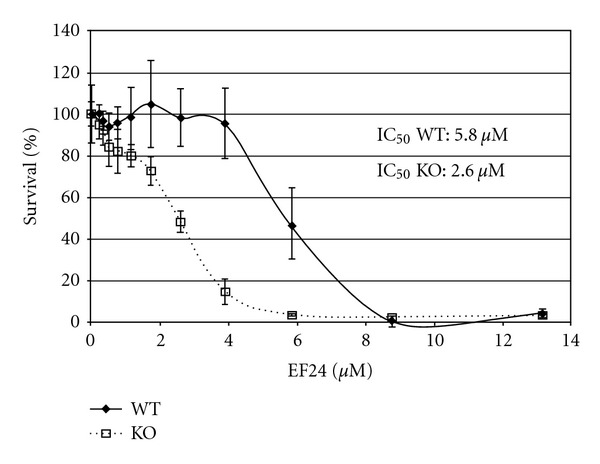

Inhibition of the FA pathway could occur at any point in the multistep FA protein network, but a key predictive readout for FA function and resistance to ICLs is the monoubiquitylation of FANCD2 [11, 55]. Several inhibitors of FANCD2 monoubiquitylation have been identified including proteasome inhibitors bortezomib and MG132, curcumin, and the curcumin analogs EF24 and 4H-TTD [19, 22, 56, 57]. Curcumin, a natural product derived from turmeric, was identified as a weak inhibitor of FANCD2 monubiquitylation in a cell-based screen [19]. We developed a cell-free assay in Xenopus egg extracts to screen small molecules for stronger and more specific inhibitors of FANCD2 monubiquitylation. Unlike cell-based screening assays for small molecules capable of inhibiting the FA pathway, the cell-free method uncouples FANCD2 monoubiquitylation from DNA replication, thus focusing more specifically on the key biochemical steps in a soluble context enriched for nuclear proteins and capable of full genomic replication [22]. Screening in egg extracts identified 4H-TTD, a compound with structural similarity to curcumin as an inhibitor, and this inhibitory effect was verified in human cells [22, 57]. A series of curcumin analogs were also tested, including EF24, a potent monoketone analog of curcumin [58, 59]. The prediction that an FA inhibitor would selectively kill ATM-deficient cells was tested in cell-based assays for synthetic lethality in ATM-proficient and ATM-deficient cells. ATM-deficient cells treated with EF24 demonstrated an increased sensitivity compared to ATM wt cells (see Figure 3) [22, 57]. The increased lethality in ATM-deficient cells provides evidence for future synthetic lethal approaches with FA pathway inhibitors in the treatment of ATM-deficient tumors, and other tumors with deficiencies in genes that are synthetically lethal with FA (see Table 1) [6, 52].

Figure 3.

EF24 is selectively toxic to ATM-deficient cells [57]. 309ATM-deficient and 334ATM wild type cells were treated with the FA pathway inhibitor EF24. Cell viability was measured after 3 days by MTS assay. Each point represents the mean of 3 repeats. Error bars represent standard deviation.

6. Conclusion and Future Directions

Understanding how the Fanconi anemia pathway functions in concert with other DNA damage response networks is essential for understanding genomic stability and for exploiting synthetic lethality for new cancer treatments. New chemotherapeutic agents could be developed by identifying potent and specific inhibitors of the FA pathway, for example, by screening for compounds that inhibit key FA pathway steps (e.g., monoubiquitylation and deubiquitylation of FANCD2/FANCI). While a long-term defect in the function of the FA pathway would result in genomic instability, short-term inhibition could provide a treatment strategy for tumors with deficiencies in certain other DNA repair pathways. Stringent identification of additional genes with synthetic lethal relationships with the FA pathway, and identification of malignancies with deficiencies or mutations in genes that are synthetic lethal with FA will be required for these tailored therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funds from the Medical Research Fund of Oregon.

References

- 1.Wang W. Emergence of a DNA-damage response network consisting of Fanconi anaemia and BRCA proteins. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8(10):735–748. doi: 10.1038/nrg2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Winter JP, Joenje H. The genetic and molecular basis of Fanconi anemia. Mutation Research. 2009;668(1-2):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takata H, Tanaka Y, Matsuura A. Late S phase-specific recruitment of Mre11 complex triggers hierarchical assembly of telomere replication proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular Cell. 2005;17(4):573–583. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan Z, Delannoy M, Ling C, et al. A histone-fold complex and FANCM forma conserved DNA-remodeling complex to maintain genome stability. Molecular Cell. 2010;37(6):865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitao H, Takata M. Fanconi anemia: a disorder defective in the DNA damage response. International Journal of Hematology. 2011;93(4):417–424. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0777-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosado IV, Langevin F, Crossan GP, et al. Formaldehyde catabolism is essential in cells deficient for the Fanconi anemia DNA-repair pathway. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2011;18(12):1432–1434. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciccia A, Ling C, Coulthard R, et al. Identification of FAAP24, a Fanconi Anemia core complex protein that interacts with FANCM. Molecular Cell. 2007;25(3):331–343. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ling C, Ishiai M, Ali AM, et al. FAAP100 is essential for activation of the Fanconi anemia-associated DNA damage response pathway. EMBO Journal. 2007;26(8):2104–2114. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali AM, Singh PA, Singh TR, et al. FAAP20: a novel ubiquitin-binding FA nuclear core complex protein required for functional integrity of the FA-BRCA DNA repair pathway. Blood. 2012;119(14):3285–3294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-385963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim H, Yang K, Dejsuphong D, D'Andrea AD. Regulation of Rev1 by the Fanconi anemia core complex. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2012;19(2):164–170. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimamura A, De Oca RM, Svenson JL, et al. A novel diagnostic screen for defects in the Fanconi anemia pathway. Blood. 2002;100(13):4649–4654. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang K, Moldovan GL, Vinciguerra P, Murai J, Takeda S, D'Andrea AD. Regulation of the Fanconi anemia pathway by a SUMO-like delivery network. Genes and Development. 2011;25(17):1847–1858. doi: 10.1101/gad.17020911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smogorzewska A, Desetty R, Saito TT, et al. A Genetic screen identifies FAN1, a Fanconi Anemia-associated nuclease necessary for DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Molecular Cell. 2010;39(1):36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacKay C, Déclais AC, Lundin C, et al. Identification of KIAA1018/FAN1, a DNA repair nuclease recruited to DNA damage by monoubiquitinated FANCD2. Cell. 2010;142(1):65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu T, Ghosal G, Yuan J, Chen J, Huang J. FAN1 acts with FANCI-FANCD2 to promote DNA interstrand cross-link repair. Science. 2010;329(5992):693–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1192656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kratz K, Schöpf B, Kaden S, et al. Deficiency of FANCD2-associated nuclease KIAA1018/FAN1 sensitizes cells to interstrand crosslinking agents. Cell. 2010;142(1):77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shereda RD, Machida Y, Machida YJ. Human KIAA1018/FAN1 localizes to stalled replication forks via its ubiquitin-binding domain. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(19):3977–3983. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.19.13207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung Y, Lippard SJ. Direct cellular responses to platinum-induced DNA damage. Chemical Reviews. 2007;107(5):1387–1407. doi: 10.1021/cr068207j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chirnomas D, Taniguchi T, De La Vega M, et al. Chemosensitization to cisplatin by inhibitors of the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2006;5(4):952–961. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helleday T, Petermann E, Lundin C, Hodgson B, Sharma RA. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2008;8(3):193–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taniguchi T, Tischkowitz M, Ameziane N, et al. Disruption of the Fanconi anemia-BRCA pathway in cisplatin-sensitive ovarian tumors. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(5):568–574. doi: 10.1038/nm852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landais I, Sobeck A, Stone S, et al. A novel cell-free screen identifies a potent inhibitor of the fanconi anemia pathway. International Journal of Cancer. 2009;124(4):783–792. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rai R, Peng G, Li K, Lin SY. DNA damage response: the players, the network and the role in tumor suppression. Cancer Genomics and Proteomics. 2007;4(2):99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(2):123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helleday T, Bryant HE, Schultz N. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP-1) in homologous recombination and as a target for cancer therapy. Cell Cycle. 2005;4(9):1176–1178. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lord CJ, McDonald S, Swift S, Turner NC, Ashworth A. A high-throughput RNA interference screen for DNA repair determinants of PARP inhibitor sensitivity. DNA Repair. 2008;7(12):2010–2019. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weil MK, Chen AP. PARP inhibitor treatment in ovarian and breast cancer. Current Problems in Cancer. 2011;35(1):7–50. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dedes KJ, Wilkerson PM, Wetterskog D, Weigelt B, Ashworth A, Reis-Filho JS. Synthetic lethality of PARP inhibition in cancers lacking BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(8):1192–1199. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.8.15273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wysham WZ, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Li H, et al. BRCAness profile of sporadic ovarian cancer predicts disease recurrence. PLoS One. 2012;7(1, article e30042) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaye SB, Lubinski J, Matulonis U, et al. Phase II, open-label, randomized, multicenter study comparing the efficacy and safety of olaparib, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(4):372–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sessa C. Update on PARP1 inhibitors in ovarian cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2011;22(supplement 8):viii72–viii76. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guha M. PARP inhibitors stumble in breast cancer. Nature Biotechnology. 2011;29(5):373–374. doi: 10.1038/nbt0511-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weston VJ, Oldreive CE, Skowronska A, et al. The PARP inhibitor olaparib induces significant killing of ATM-deficientlymphoid tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2010;116(22):4578–4587. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Senra JM, Telfer BA, Cherry KE, et al. Inhibition of PARP-1 by olaparib (AZD2281) increases the radiosensitivity of a lung tumor xenograft. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2011;10(10):1949–1958. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Vuurden DG, Hulleman E, Meijer OLM, et al. PARP inhibition sensitizes childhood high grade glioma, medulloblastoma and ependymoma to radiation. Oncotarget. 2011;2(12):984–996. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fraser M, Zhao H, Luoto KR, et al. PTEN deletion in prostate cancer cells does not associate with loss of RAD51 function: implications for radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2012;18(4):1015–1027. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pichierri P, Averbeck D, Rosselli F. DNA cross-link-dependent RAD50/MRE11/NBS1 subnuclear assembly requires the Fanconi anemia C protein. Human Molecular Genetics. 2002;11(21):2531–2546. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.21.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mendes-Pereira AM, Martin SA, Brough R, et al. Synthetic lethal targeting of PTEN mutant cells with PARP inhibitors. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2009;1(6-7):315–322. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salmena L, Carracedo A, Pandolfi PP. Tenets of PTEN tumor suppression. Cell. 2008;133(3):403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen WH, Balajee AS, Wang J, et al. Essential role for nuclear PTEN in maintaining chromosomal integrity. Cell. 2007;128(1):157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mutter GL, Lin MC, Fitzgerald JT, et al. Altered PTEN expression as a diagnostic marker for the earliest endometrial precancers. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(11):924–931. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.11.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marsit CJ, Zheng S, Aldape K, et al. PTEN expression in non-small-cell lung cancer: evaluating its relation to tumor characteristics, allelic loss, and epigenetic alteration. Human Pathology. 2005;36(7):768–776. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung, cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304(5676):1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jang KS, Song YS, Jang SH, et al. Clinicopathological significance of nuclear PTEN expression in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 2010;56(2):229–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darido C, Georgy SR, Wilanowski T, et al. Targeting of the tumor suppressor GRHL3 by a miR-21-dependent proto-oncogenic network results in PTEN loss and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(5):635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia Pedrero JM, Garcia Carracedo D, Muñoz Pinto C, et al. Frequent genetic and biochemical alterations of the PI 3-K/AKT/PTEN pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;114(2):242–248. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Kristensen GB, Helland A, Nesland JM, Børresen-Dale AL, Holm R. Protein expression and prognostic value of genes in the erb-b signaling pathway in advanced ovarian carcinomas. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2005;124(3):392–401. doi: 10.1309/BL7E-MW66-LQX6-GFRP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsao H, Mihm MC, Sheehan C. PTEN expression in normal skin, acquired melanocytic nevi, and cutaneous melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2003;49(5):865–872. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)02473-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li L, Dutra A, Pak E, et al. EGFRvIII expression and PTEN loss synergistically induce chromosomal instability and glial tumors. Neuro-Oncology. 2009;11(1):9–21. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang J, Ren Y, Wang L, et al. PTEN mutation spectrum in breast cancers and breast hyperplasia. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2010;136(9):1303–1311. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0781-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmitz M, Grignard G, Margue C, et al. Complete loss of PTEN expression as a possible early prognostic marker for prostate cancer metastasis. International Journal of Cancer. 2007;120(6):1284–1292. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kennedy RD, Chen CC, Stuckert P, et al. Fanconi anemia pathway-deficient tumor cells are hypersensitive to inhibition of ataxia telangiectasia mutated. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117(5):1440–1449. doi: 10.1172/JCI31245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang NY, Greiner TC, Weisenburger DD, et al. Oligonucleotide microarrays demonstrate the highest frequency of ATM mutations in the mantle cell subtype of lymphoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(9):5372–5377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831102100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haidar MA, Kantarjian H, Manshouri T, et al. ATM gene deletion in patients with adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2000;88(5):1057–1062. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000301)88:5<1057::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garcia-Higuera I, Taniguchi T, Ganesan S, et al. Interaction of the Fanconi anemia proteins and BRCA1 in a common pathway. Molecular Cell. 2001;7(2):249–262. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacquemont C, Taniguchi T. Proteasome function is required for DNA damage response and fanconi anemia pathway activation. Cancer Research. 2007;67(15):7395–7405. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Landais I, Hiddingh S, McCarroll M, et al. Monoketone analogs of curcumin, a new class of Fanconi anemia pathway inhibitors. Molecular Cancer. 2009;8, article 133 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adams BK, Cai J, Armstrong J, et al. EF24, a novel synthetic curcumin analog, induces apoptosis in cancer cells via a redox-dependent mechanism. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2005;16(3):263–275. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adams BK, Ferstl EM, Davis MC, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel curcumin analogs as anti-cancer and anti-angiogenesis agents. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;12(14):3871–3883. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen MJ, Dumitrache LC, Wangsa D, et al. Cisplatin depletes TREX2 and causes robertsonian translocations as seen in TREX2 knockout cells. Cancer Research. 2007;67(19):9077–9083. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pizem J, Popovic M, Cör A. Expression of Gli1 and PARP1 in medulloblastoma: an immunohistochemical study of 65 cases. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2011;103(3):459–467. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barton VN, Donson AM, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Gore L, Liu AK, Foreman NK. PARP1 expression in pediatric central nervous system tumors. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2009;53(7):1227–1230. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Domagala P, Huzarski T, Lubinski J, Gugala K, Domagala W. PARP-1 expression in breast cancer including BRCA1-associated, triple negative and basal-like tumors: possible implications for PARP-1 inhibitor therapy. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2011;127(3):861–869. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu X, Lei M, Erikson RL. Normal cells, but not cancer cells, survive severe Plk1 depletion. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006;26(6):2093–2108. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2093-2108.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shekhar MPV, Lyakhovich A, Visscher DW, Heng H, Kondrat N. Rad6 overexpression induces multinucleation, centrosome amplification, abnormal mitosis, aneuploidy, and transformation. Cancer Research. 2002;62(7):2115–2124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bartkova J, Zemanova M, Bartek J. Expression of CDK7/CAK in normal and tumor cells of diverse histogenesis, cell-cycle position and differentiation. International Journal of Cancer. 1996;66(6):732–737. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960611)66:6<732::AID-IJC4>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bouwman P, Aly A, Escandell JM, et al. 53BP1 loss rescues BRCA1 deficiency and is associated with triple-negative and BRCA-mutated breast cancers. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2010;17(6):688–695. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shinmura K, Tao H, Goto M, et al. Inactivating mutations of the human base excision repair gene NEIL1 in gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(12):2311–2317. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hiramoto T, Nakanishi T, Sumiyoshi T, et al. Mutations of a novel human RAD54 homologue, RAD54B, in primary cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18(22):3422–3426. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McManus KJ, Barrett IJ, Nouhi Y, Hieter P. Specific synthetic lethal killing of RAD54B-deficient human colorectal cancer cells by FEN1 silencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(9):3276–3281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813414106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang MH, Chiang WC, Chou TY, et al. Increased NBS1 expression is a marker of aggressive head and neck cancer and overexpression of NBS1 contributes to transformation. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12(2):507–515. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shibata T, Kokubu A, Miyamoto M, Sasajima Y, Yamazaki N. Mutant IDH1 confers an in vivo growth in a melanoma cell line with BRAF mutation. American Journal of Pathology. 2011;178(3):1395–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stankovic T, Stewart GS, Fegan C, et al. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated-deficient B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia occurs in pregerminal center cells and results in defective damage response and unrepaired chromosome damage. Blood. 2002;99(1):300–309. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang P, Bhakta KS, Puri PL, Newbury RO, Feramisco JR, Wang JY. Association of ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) gene mutation/deletion with rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Biology and Therapy. 2003;2(1, article 2):87–91. doi: 10.4161/cbt.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tommiska J, Bartkova J, Heinonen M, et al. The DNA damage signalling kinase ATM is aberrantly reduced or lost in BRCA1/BRCA2-deficient and ER/PR/ERBB2-triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27(17):2501–2506. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]