Abstract

How is the extensibility of growing plant cell walls regulated? In the past, most studies have focused on the role of the cellulose/xyloglucan network and the enigmatic wall-loosening agents expansins. Here we review first how in the closest relatives of the land plants, the Charophycean algae, cell wall synthesis is coupled to cell wall extensibility by a chemical Ca2+-exchange mechanism between Ca2+–pectate complexes. We next discuss evidence for the existence in terrestrial plants of a similar “primitive” Ca2+–pectate-based growth control mechanism in parallel to the more recent, land plant-specific, expansin-dependent process.

Keywords: pectin, pectin methylesterase, wall extensibility, Chara corallina

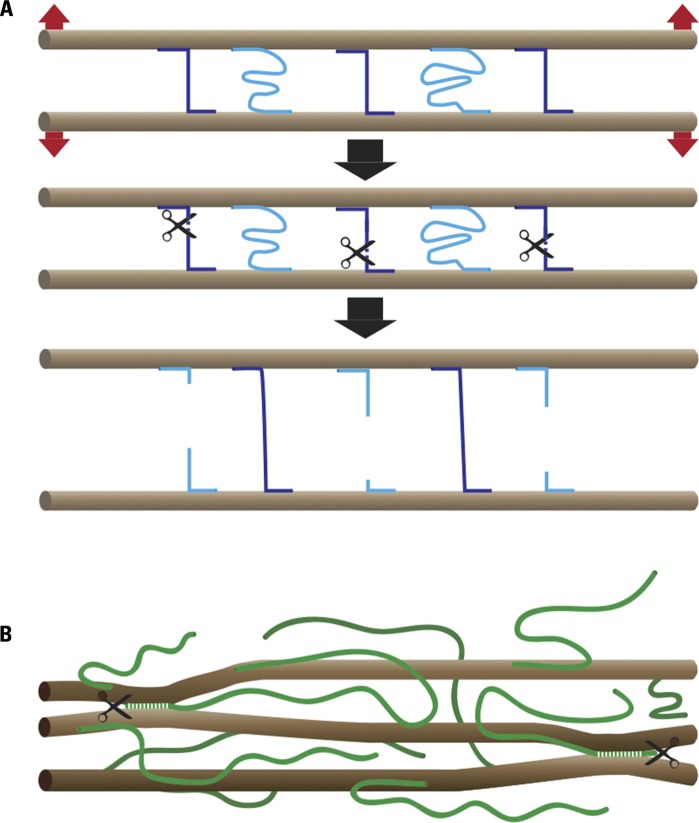

Plant cell growth reflects the balance between the extensibility of the cell wall and the forces exerted on the wall by the turgor pressure. Although growth in principle can be controlled by changing either parameter, in most documented cases growth changes reflect changes in cell wall extensibility (Cosgrove, 2005). The paradoxical properties of cell walls, which combine extensibility with extreme strength, can be easily understood by keeping in mind that wall strength is determined by the number and strength of load-bearing bonds and by assuming that a wall relaxation mechanism exists that can break these bonds and transfer the load to new bonds (Figure 1). Wall relaxation and cell expansion can occur, in principle, with or without a change in wall strength, depending on whether or not this chemorheological process causes a net change in the number or strength of the load-bearing bonds.

FIGURE 1.

Chemorheological control of wall extensibility. (A) Principle: microfibrils (brown), which in most cases form parallel arrays, are cross-linked by load-bearing (violet) and relaxed (light blue) bonds. The number and strength of the load-bearing bonds determines cell wall strength. Wall extensibility is controlled by chemorheological mechanisms that remove load-bearing bonds. The cell wall relaxes and undergoes turgor-driven mechanical deformation until previously relaxed bonds become load-bearing. (B) Cartoon of cell wall architecture showing microfibrils (brown) and XG chains (green). A small portion of the XG is intertwined or complexed with cellulose, thus sticking the microfibrils together at these points. The endoglucanase Cel12A as well as expansin may act on these relatively inaccessible XG–cellulose interaction domains.

THE NATURE OF THE LOAD-BEARING BONDS IN PRIMARY CELL WALLS

Typical primary cell walls (i.e., the walls of growing cells) consist of strong cellulose microfibrils, hemicelluloses [primarily xyloglucans (XGs) in non-Commelinoid species], pectins, and structural proteins. The current “textbook view” of the control of cell wall extensibility (Carpita and McCann, 2000) is largely based on a series of seminal extensometer experiments, which showed that acid-promoted wall extension under a constant tension, also referred to as creep, can be reproduced on isolated walls. These studies led to the purification of a creep-promoting agent, called expansin (McQueen-Mason et al., 1992). Expansins are encoded by large gene families, the expression of whose members is frequently correlated with growth. All attempts so far have failed to detect enzymatic activity for expansins. Interestingly, the proteins can also promote creep of paper, essentially pure cellulose, without detectable cellulose hydrolysis. From this it was concluded that expansins have a “lubricating” activity perhaps by severing hydrogen bonds between glucan chains (cellulose and/or XG; Cosgrove, 2000). XG chains strongly bind to microfibrils and in principle are long enough to bridge microfibrils in the wall. Cross-links have been observed in certain cell wall preparations (McCann et al., 1993). This led to the so called “tethered network” model in which the main load-bearing network consists of cellulose–XGs, the extensibility of which is controlled by expansin and perhaps wall-bound XG endo-transglycosylase (XET) activity (Fry et al., 1992). The latter can stitch XG fragments together and, if a transfer from load-bearing to relaxed XG chains occurs, this process also has the potential to promote creep.

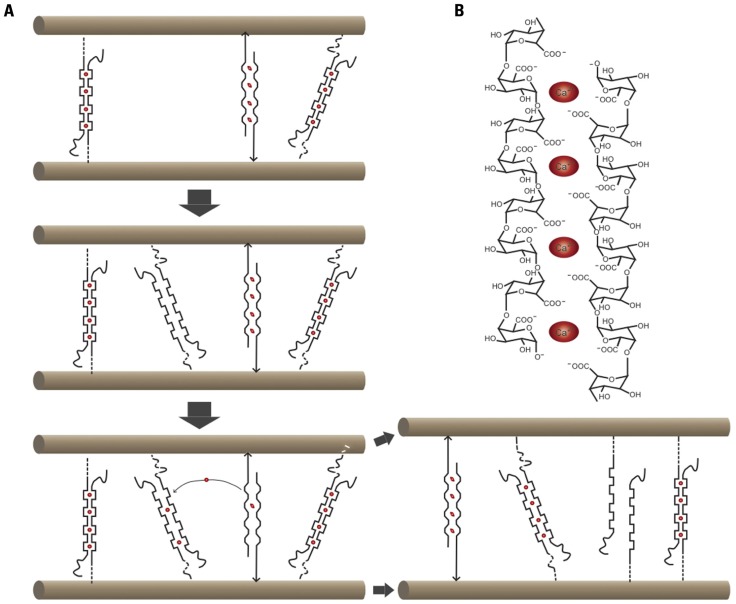

Within this view, pectins form a matrix around the cellulose–XG network but are thought not to have a major load-bearing role (Cosgrove, 1999). Pectins are block co-polymers; homogalacturonan (HG), a main pectic polymer, consists of a-1,4-linked galacturonic acids. HG is secreted in a highly methylesterified form and selectively de-methylesterified by pectin methylesterases (PME; Pelloux et al., 2007). After de-methylesterification, pectate can form Ca2+–pectate cross-linked complexes, referred to as “eggboxes” (Figure 2B; Grant et al., 1973). These cross-links, together with rhamnogalacturonan II (RGII)-boron diester bonds, are thought to indirectly affect the cellulose–XG network by influencing the wall porosity and hence the accessibility of primary wall relaxation proteins to their substrate (Cosgrove, 1999). The more Ca2+–pectate present, the denser the gel and the more inextensible the cell wall is expected to be.

FIGURE 2.

Cartoon summarizing Ca 2+–pectate-dependent growth control in the alga Chara corallina. (A) In this species, cellulose microfibrils are parallel and oriented transversely to the elongation axis. Ca2+ (red ovals)-pectate complexes are load-bearing. One stretched and two relaxed Ca2+–pectate complexes are shown. Newly deposited pectate will chelate Ca2+ preferentially out of the stretched complexes, thus leading to wall relaxation and turgor-driven mechanical deformation until other complexes become load-bearing. (B) Cartoon of an “eggbox” consisting of two antiparallel poly-galacturonic acid chains complexed by Ca2+.

Recent observations necessitate a reconsideration of the “tethered network” model. Firstly, 3D-solid state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies suggest that at best only a small proportion of the XG is bound to cellulose (Dick-Perez et al., 2011). Secondly, extensometer assays on isolated cucumber cell walls show that creep is promoted by a specific class of dual-specificity β-1,4-endo-glucanases (EGases) and not by XG- or cellulose-specific EGases (Park and Cosgrove, 2012). Based on these studies, the authors propose a model for the cell wall architecture (Figure 1B), in which minor and relatively inaccessible XG fractions are intertwined or complexed with cellulose and thus form a small number of load-bearing connections between microfibrils. The authors propose that these connections also may be the target not only of the dual-specificity EGases but also of expansins. Why would there be so few cellulose–XG interaction sites, given the high affinity of XG for cellulose (Hanus and Mazeau, 2006)? An interesting possibility is that pectin competes with XG for interaction with nascent cellulose chains, perhaps through the binding of the arabinan and galactan side chains to the cellulose (Zykwinska et al., 2005). In this case the secreted pectin/XG ratio as well as the pectin structure (the density and length of side chains) would determine the extent of the cellulose–XG interactions. Thirdly, a double mutant (xylosyltransferase1/2 or xt1xt2) without detectable XG (Cavalier et al., 2008) shows a surprisingly subtle phenotype: mutant plants are slightly smaller than the wild type, but otherwise nearly normal in their development. Stress–strain assays on cell walls from petioles showed a 53% higher elastic compliance and a 164% higher plastic compliance for XG-less walls as compared to wild type walls, confirming that XGs have a wall-strengthening role (Park and Cosgrove, 2011). In contrast, xt1xt2 cell walls showed strongly reduced acid-promoted/expansin-dependent creep, consistent with a reduced effectiveness of expansin in the absence of XG. Surprisingly, treatments that specifically act on pectate or xylans promoted creep more strongly in the mutant than in the wild type, showing that Ca2+–pectate and, to a lesser extent, xylans are load-bearing in the mutant (Park and Cosgrove, 2011). These findings are reminiscent of the results on tomato cell cultures continually exposed to the cellulose inhibitor dichlorobenil (DCB); the walls of DCB habituated cells strikingly lacked cellulose and XG, and were held together by a strong pectate network, reinforced by phenolic ester and/or phenolic ether bonds (Shedletzky et al., 1990). In conclusion, in the absence of the cellulose–XG network, pectate cross-links play a major load-bearing role.

Another set of recent observations on the Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem underscore the importance of pectin metabolism in the control of wall extensibility also during normal development (Peaucelle et al., 2008, 2011). Microindentation using atomic force microscopy (AFM) showed that the appearance of organ primordia at the periphery of the meristem was preceded by an increased elastic compliance of the cell walls at that position. This could be attributed to the de-methylesterification of HG. Indeed, inhibition of PME activity by the ectopic expression of a PME inhibitor (PMEI) led to a global stiffening of the walls throughout the meristem and totally prevented the formation of primordia, whereas ectopic PME expression reduced the cell wall stiffness and caused the formation of ectopic primordia (Peaucelle et al., 2008).

This raises the following questions: (1) To what extent do pectin cross-links also have a load-bearing role in normal cell walls? (2) How can we explain the association of HG de-methylesterification with a decrease in cell wall stiffness rather than the expected increase in stiffness? and more in general (3) What is the relevance of the changes in cell wall stiffness for the observed growth changes?

AN EVOLUTIONARY PERSPECTIVE ON GROWTH CONTROL

To provide an answer to these questions it is worthwhile to consider the growth mechanisms revealed in freshwater algae of the Charophyceae family, the closest relatives of land plants. Chara corallina, with its giant cells of up to several centimeters long, is ideally suited for the study of cell expansion. Chara cells can be easily impaled with a pipette, allowing the composition of the cytosol and the turgor pressure to be controlled. In addition, the cytoplasm can be removed entirely to study the expansion behavior of isolated walls (Proseus et al., 2000). The cell wall of Chara has a composition similar to that of higher plants with cellulose, pectin (primarily non-methyl-esterified HG), and minor amounts of XG (Sorensen et al., 2011). The results of a series of imaginative experiments on this species by the Boyer laboratory yielded an elegant model for wall expansion (Figure 2; for a recent review, see Boyer, 2009). Ca2+–pectate cross-links are the main load-bearing bonds, and wall relaxation is coupled to pectate deposition through a simple non-enzymatic mechanism: Newly deposited pectate chelates Ca2+ away from existing Ca2+–pectate, preferentially from the load-bearing bonds that are distorted by the wall tension. The loss of these Ca2+–pectate bonds causes the cell wall to relax and irreversible wall extension occurs. The new Ca2+–pectate then binds to the wall and the extension decelerates. New pectate is deposited and the cycle repeats itself.

A similar coupling mechanism may underlie growth control in tip-growing cells of land plants as shown by the mathematical modeling of growing pollen tubes (Rojas et al., 2011). An elegant model was developed based on the idea, similar to that proposed for Chara, that newly generated pectate causes turnover of load-bearing Ca2+–pectate cross-links, thereby facilitating turgor-driven mechanical deformation. In this model, pectate production is the resultant of the deposition and de-methylesterification of pectin. Interestingly, the validity of the model was supported by its ability to precisely reproduce the morphologies of pollen tubes; to predict the growth oscillations observed in rapidly growing pollen tubes and the observed phase relationships between variables such as wall thickness, cell morphology, and growth rate in oscillatory cells (Rojas et al., 2011).

WHAT ABOUT DIFFUSELY GROWING CELLS IN LAND PLANTS?

A number of older studies have also provided evidence for a role of pectin cross-links in growth control of non-tip-growing cells of land plants: high concentrations of Ca2+ inhibit growth and acid-promoted extensibility of isolated cell wall preparations (Tagawa and Bonner, 1957), whereas chelation of Ca2+ strongly promotes cell wall extensibility and growth (Weinstein et al., 1956). It was concluded that, like in Chara, Ca2+–pectate cross-links have a load-bearing role and that the exchange of pectate-bound Ca2+ for H+ may explain at least in part the acid-promoted increase in cell wall extensibility (Virk and Cleland, 1988). An elegant study based on stress–strain experiments on glycerinated hollow cylinders prepared from elongating regions of soybean hypocotyls addressed this issue in more detail (Nakahori et al., 1991; Ezaki et al., 2005). It was shown that a pH shift in the physiological range from 6 to 5 simultaneously caused a strong increase in the extensibility, and a decrease in the yield threshold of the cell wall. Interestingly, high Ca2+ concentrations reverted this increase in extensibility but did not affect the yield threshold. A Ca2+ chelator perfectly mimicked at pH 6 the acid-induced increase in wall extensibility (Ezaki et al., 2005). The reduction in the yield threshold in the pH 6–5 range was almost entirely due to a heat-sensitive component (possibly the protein “yieldin”; Okamoto-Nakazato, 2002). Instead, the acid-induced extensibility increase was comprised of a heat-sensitive (presumably expansin) and a heat-insensitive, Ca2+–pectate-dependent component. Pectin can also play a load-bearing role in mature cells after growth cessation as shown in cucumber hypocotyls (Zhao et al., 2008). Indeed, during maturation these cells lose the ability to grow and to respond to expansin. Interestingly, expansin-dependent extension could be restored in heat-inactivated walls of non-growing hypocotyl cells upon treatment with fungal pectinases or chelation of Ca2+ (Zhao et al., 2008).

Together these experiments can be interpreted as follows: the cell walls of the land plants studied have at least two integrated load-bearing components, Ca2+–pectate and cellulose–XG. Growth control involves an “ancient” process elaborated upon the Ca2+–pectate exchange mechanism, inherited from the Charophycean ancestors, combined with a more “recent” land plant-specific, expansin-based process, which “amplifies” the Ca2+–pectate mechanism and allows faster growth. In this context it is interesting to note that the cell expansion rate of land plants can be 5–20× faster than that of Chara (Boyer, 2009).

The Ca-pectate growth-controlling mechanism is a system that, in the absence of app ropriate compensation mechanisms, would be very sensitive to environmental fluctuations in Ca2+ or other divalent or monovalent cations. The latter would compete with Ca2+ for pectate binding and hence potentially interfere with cell wall integrity. The large amounts of HG (e.g., 23% of the cell walls in Arabidopsis leaves), combined with a precise regulation of the degree of methylesterification provides an important buffering capacity to compensate for changes in cation concentrations for instance during salt or drought stress. Growth control would require that the amount of pectate is precisely tuned, for instance through a mechanism that detects the presence of pectate in the cell wall and that controls the deposition of pectin, PME activity and/or pectate turnover. Pectate-binding receptor-like kinases, such as wall-associated kinases (WAKs; Kohorn, 2001) might play such a sensing role.

PERSPECTIVES

The combination of recent developments in live-cell imaging, spectroscopy, the mechanical measurement of cell walls, mathematical modeling, and the use of biomimetic systems should open the way for the study of a number of previously intractable processes involved in growth control in plants: (1) The study of the deposition, de-methylesterification, and turnover of pectin in vivo. A promising new tool based on the in vivo fluorescent labeling of polysaccharides using click chemistry has been developed recently. The technique already allowed pectin deposition and turnover to be visualized in living root cells (Anderson et al., 2012). (2) The quantification at different growth stages of wall-bound Ca 2+ in different layers of the cell wall . A promising technique is secondary ion mass spectroscopy (SIMS; Follet-Gueye et al., 1998). (3) The study of the cell wall architecture and the interactions between polymers. This can be done on intact cell walls using 3D-solid state NMR (Dick-Perez et al., 2011) or on reconstructed polymer composites with a large panel of physical techniques (Cerclier et al., 2010; Valentin et al., 2010). (4) The dissection of feedback signaling pathways involved in the mechanical homeostasis of the cell wall. This can be addressed using forward genetics combined with the identification and functional analysis of pectate-binding plasma membrane receptors. (5) The study of growth-associated changes in wall mechanics of individual cells using micro- or nano-indentation methods. For instance, high time-resolution microindentation studies on pollen tubes with oscillating growth patterns showed that increases in cell wall elasticity (presumably corresponding to cell wall relaxation cycles) preceded increases in growth rate (Zerzour et al., 2009). The observation of changes in cell wall mechanics over longer time scales may or may not be relevant for growth control. For instance, auxin- or brassinosteroid promoted growth acceleration appears to be initiated by the hydration of the cell wall (Caesar et al., 2011). This highly relevant process may simultaneously cause an increase in the elasticity and the extensibility of the wall. Similarly, oxidative cross-linking of proteins or phenolics at the end of growth phases or during stresses, simultaneously causes wall stiffening and growth arrest (Monshausen and Gilroy, 2009). On the other hand, the chemorheological process that causes wall relaxation by replacing existing bonds for bonds at new positions in principle can occur irrespective of the number and strength of the cross-links that determine the stiffness of the cell wall. For instance, growth inhibition by blue light occurred in the absence of detectable changes in the viscoelastic properties of the cell wall (Cosgrove, 1988). Finally (6) mathematical modeling will be essential to establish explicit frameworks for the experimental evaluation of relevant parameters (Rojas et al., 2011; Dyson et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2012).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Pierre Van Cutsem, Simon Mc Queen-Mason, and Renaud Bastien for inspiring discussions. Part of the work was funded by Agence Nationale de la Recherche projects ANR-08-BLANC-0292 “Wallintegrity,” ANR-09-BLANC-0007-01 “Growpec,” ANR-10-BLAN-1516 “Mechastem,” and the EU FP7 project “AGRON-OMICS.” Siobhan Braybrook is funded by a United States National Science Foundation International Research Fellowship (Award No. OISE-0853105).

REFERENCES

- Anderson C. T., Wallace I. S., Somerville C. R. (2012). Metabolic click-labeling with a fucose analog reveals pectin delivery, architecture, and dynamics in Arabidopsis cell walls. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 1329–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer J. S. (2009). Cell wall biosynthesis and the molecular mechanism of plant enlargement. Funct. Plant Biol. 36 383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caesar K., Elgass K., Chen Z., Huppenberger P., Witthoft J., Schleifenbaum F., Blatt M. R., Oecking C., Harter K. (2011). A fast brassinolide-regulated response pathway in the plasma membrane of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 66 528–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita N., McCann M. (2000). “The cell wall,” in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants, eds Buchanan B., Gruissem W., Jones R. (Rockville, MD: American Society of Plant Physiologists; ), 52–108 [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier D. M., Lerouxel O., Neumetzler L., Yamauchi K., Reinecke A., Freshour G., Zabotina O. A., Hahn M. G., Burgert I., Pauly M., Raikhel N. V., Keegstra K. (2008). Disrupting two Arabidopsis thaliana xylosyltransferase genes results in plants deficient in xyloglucan, a major primary cell wall component. Plant Cell 20 1519–1537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerclier C., Cousin F., Bizot H., Moreau C., Cathala B. (2010). Elaboration of spin-coated cellulose–xyloglucan multilayered thin films. Langmuir 26 17248–17255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D. J. (1988). Mechanism of rapid suppression of cell expansion in cucumber hypocotyls after blue-light irradiation. Planta 176 109–116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D. J. (1999). Enzymes and other agents that enhance cell wall extensibility. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50 391–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D. J. (2000). Loosening of plant cell walls by expansins. Nature 407 321–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D. J. (2005). Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6 850–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick-Perez M., Zhang Y., Hayes J., Salazar A., Zabotina O. A., Hong M. (2011). Structure and interactions of plant cell-wall polysaccharides by 2D and 3D Magic-Angle-Spinning Solid-State NMR. Biochemistry 50 989–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson R. J., Band L. R., Jensen O. E. (2012). A model of crosslink kinetics in the expanding plant cell wall: yield stress and enzyme action. J. Theor. Biol. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.04.035 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezaki N., Kido N., Takahashi K., Katou K. (2005). The role of wall Ca2+ in the regulation of wall extensibility during the acid-induced extension of soybean hypocotyl cell walls. Plant Cell Physiol. 46 1831–1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follet-Gueye M. L., Verdus M. C., Demarty M., Thellier M., Ripoll C. (1998). Cambium pre-activation in beech correlates with a strong temporary increase of calcium in cambium and phloem but not in xylem cells. Cell Calcium 24 205–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry S. C., Smith R. C., Renwick K. F., Martin D. J., Hodge S. K., Matthews K. J. (1992). Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase, a new wall-loosening enzyme activity from plants. Biochem. J. 282 821–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant G. T., Morris E. R., Rees D., Smith P. J. C., Thom D. (1973). Biological interactions between polysaccharides and divalent cations: the “egg-box” model. FEBS Lett. 32 195–198 [Google Scholar]

- Hanus J., Mazeau K. (2006). The xyloglucan–cellulose assembly at the atomic scale. Biopolymers 82 59–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R., Becker A. A., Jones I. A. (2012). Modelling cell wall growth using a fibre-reinforced hyperelastic–viscoplastic constitutive law. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 60 750–783 [Google Scholar]

- Kohorn B. D. (2001). WAKs; cell wall associated kinases. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13 529–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann M. C., Stacey N. J., Wilson R., Roberts K. (1993). Orientation of macromolecules in the walls of elongating carrot cells. .J. Cell Sci. 106 1347–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen-Mason S., Durachko D. M., Cosgrove D. J. (1992). Two endogenous proteins that induce cell wall extension in plant. Plant Cell 4 1425–1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monshausen G. B., Gilroy S. (2009). Feeling green: mechanosensing in plants. Trends Cell Biol. 19 228–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahori K., Katou K., Okamoto H. (1991). Auxin changes both the extensibility and the yield threshold of the cell wall of Vigna hypocotyls. Plant Cell Physiol. 32 121–129 [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto-Nakazato A. (2002). A brief note on the study of yieldin, a wall-bound protein that regulates the yield threshold of the cell wall. J. Plant Res. 115 309–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. B., Cosgrove D. J. (2011). Changes in cell wall biomechanical properties in the xyloglucan-deficient xxt1/xxt2 mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 158 465–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. B., Cosgrove D. J. (2012). A revised architecture of primary cell walls based on biomechanical changes induced by substrate-specific endoglucanases. Plant Physiol. 158 1933–1943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle A., Braybrook S. A., Le Guillou L., Bron E., Kuhlemeier C., Hofte H. (2011). Pectin-induced changes in cell wall mechanics underlie organ initiation in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 21 1720–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle A., Louvet R., Johansen J. N., Hofte H., Laufs P., Pelloux J., Mouille G. (2008). Arabidopsis phyllotaxis is controlled by the methyl-esterification status of cell-wall pectins. Curr. Biol. 18 1943–1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelloux J., Rusterucci C., Mellerowicz E. J. (2007). New insights into pectin methylesterase structure and function. Trends Plant Sci. 12 267–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proseus T. E., Zhu G. L., Boyer J. S. (2000). Turgor, temperature and the growth of plant cells: using Chara corallina as a model system. J. Exp. Bot. 51 1481–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas E. R., Hotton S., Dumais J. (2011). Chemically mediated mechanical expansion of the pollen tube cell wall. Biophys. J. 101 1844–1853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shedletzky E., Shmuel M., Delmer D. P., Lamport D. T. (1990). Adaptation and growth of tomato cells on the herbicide 2,6-dichlorobenzonitrile leads to production of unique cell walls virtually lacking a cellulose–xyloglucan network. Plant Physiol. 94 980–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen I., Pettolino F. A., Bacic A., Ralph J., Lu F., O’Neill M. A., Fei Z., Rose J. K., Domozych D. S., Willats W. G. (2011). The Charophycean green algae provide insights into the early origins of plant cell walls. Plant J. 68 201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagawa T., Bonner J. (1957). Mechanical properties of the Avena coleoptile as related to auxin and to ionic interactions. Plant Physiol 32 207–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin R., Cerclier C., Geneix N., Aguie-Beghin V., Gaillard C., Ralet M. C., Cathala B. (2010). Elaboration of extensin-pectin thin film model of primary plant cell wall. Langmuir 26 9891–9898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virk S. S., Cleland R. (1988). Calcium and the mechanical properties of soybean hypocotyl cell walls: possible role of calcium and protons in cell-wall loosening. Planta 176 60–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein L. H., Meiss A. N., Uhler R. L., Purvis E. R. (1956). Growth-promoting effects of ethylene-diamine tetra-acetic acid. Nature 178 1188 [Google Scholar]

- Zerzour R., Kroeger J., Geitmann A. (2009). Polar growth in pollen tubes is associated with spatially confined dynamic changes in cell mechanical properties. Dev. Biol. 334 437–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Yuan S., Wang X., Zhang Y., Zhu H., Lu C. (2008). Restoration of mature etiolated cucumber hypocotyl cell wall susceptibility to expansin by pretreatment with fungal pectinases and EGTA in vitro. Plant Physiol. 147 1874–1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zykwinska A. W., Ralet M. C., Garnier C. D., Thibault J. F. (2005). Evidence for in vitro binding of pectin side chains to cellulose. Plant Physiol. 139 397–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]