Abstract

Objectives

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue is a standard method of specimen preservation for hospital pathology departments. FFPE tissue banks are a resource of histologically-characterized specimens for retrospective biomarker investigation. We aim to establish liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis of FFPE pancreatic tissue as a suitable strategy for the study of the pancreas proteome.

Methods

We investigated the proteomic profile of FFPE pancreatic tissue specimens, using LC-MS/MS, from 9 archived specimens that were histologically-classified as: normal (n=3), chronic pancreatitis (n=3), and pancreatic cancer (n=3).

Results

We identified 525 non-redundant proteins from 9 specimens. Implementing our filtering criteria, 78, 15, and 21 proteins were identified exclusively in normal, chronic pancreatitis, and pancreatic cancer specimens, respectively. Several proteins were identified exclusively in specimens with no pancreatic disease: spink1, retinol dehydrogenase, and common pancreatic enzymes. Similarly, proteins were identified exclusively in chronic pancreatitis specimens: collagen α1(XIV), filamin A, collagen α3(VI), and SNC73. Proteins identified exclusively in pancreatic cancer included: annexin 4A and fibronectin.

Conclusions

We report that differentially-expressed proteins can be identified among FFPE tissues specimens originating from individuals with different pancreatic histologies. The mass spectrometry-based methodology used herein has the potential to enhance biomarker discovery and chronic pancreatitis research.

Keywords: pancreas, pancreas tissue, biomarker, chronic pancreatitis, FFPE, pancreatic cancer

Introduction

Diseases of the pancreas affect greater than 1 million persons in the United States annually, resulting in nearly $3 billion in direct and indirect medical costs 1. The development of a better understanding of the biomolecular mechanisms of pancreatic diseases, such as chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer, represents an important step in treatment aimed to modify or retard disease progression before end-stage disease complications occur.

Organ-specific biomarker discovery studies often analyze easily obtainable body fluids, such as serum and urine 2–5. Because systemic fluids are representative of the entire body, they are more prone to confounding factors resulting from the effects of other diseases. In addition, low abundance biomarkers may be vastly diluted among other serum and urine proteins. One alternative strategy is to study proximal body fluids, which bathe the organ of interest. Due to the vast disparity by which these specimens are collected, stored, and processed, meaningful inter-laboratory data comparisons have been limited in scope. Recent efforts have been made to standardize specimen collection, handling, and storage of various body fluids 2, 3, 6–12. However, analogous methodologies for optimized proteomic analysis of archived pathology specimens have yet to be established.

The gold-standard of specimen preservation for hospital pathology departments is formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue. FFPE tissue banks offer a vast resource for retrospective protein biomarker investigation. Such specimens have historically been used to investigate the cellular localization of specific proteins via immunohistochemistry (IHC) 13. However, IHC requires a priori knowledge of proteins to be specifically targeted and this technique is not suitable for large-scale protein identification. The application of state-of-the-art proteomics techniques to such tissue repositories may enhance our understanding of the biomolecular mechanisms of disease in a particular organ.

Mass-spectrometry-based proteomics is quickly becoming the quintessential strategy for unbiased large-scale protein investigation 14. Archived FFPE pancreatic tissue specimens offer an alternative method to investigate biochemical pathways and to discover biomarkers of pancreatic disease. Analogous techniques have been applied previously to FFPE tissues from various organs 15. A recent study has investigated pancreatic cancer FFPE tissue using a Liquid Tissue workflow for a global proteomics analysis 16. However, to our knowledge, we report the first comparison of normal, chronic pancreatitis, and pancreatic cancer FFPE pancreas tissue.

As a proof of principle, we compare the proteomic profile of FFPE pancreatic tissue specimens histologically-classified as: a) no pancreatic disease, b) chronic pancreatitis, and c) pancreatic cancer.

The major objectives of this proteomic investigation are:

prepare FFPE pancreatic tissue for proteomic analysis,

identify proteins present in FFPE pancreatic tissue using liquid chromatography-coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS),

compare the protein profiles isolated from the aforementioned specimens, and

investigate differences in characteristics (e.g., localization, function, and biological pathways) of the proteins across cohorts.

We aim to establish LC-MS/MS analysis of FFPE pancreatic tissue as a viable strategy for the study of the pancreas proteome.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

Proteomic analysis of archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) pancreas tissue in an academic center.

Study population

This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (IRB # 2007-P-002480/1).

Materials

Heptane (product #51750) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Pep-clean C18 spin columns (product # 89870) were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA). Other reagents and solvents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Burdick & Jackson (Morristown, NJ), respectively.

Formalin fixing and paraffin embedded of pancreatic tissue

FFPE tissue specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 h (Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center research pathology core). Routine paraffin treatment was as follows: Specimens were treated with 70% ethanol for 45 min twice, 80% ethanol for 60 min twice, 95% ethanol for 60 min twice, 100% ethanol for 60 min three times, followed by #83 Xylene substitute for 60 min twice and paraffin for 60 min twice. For tissue microdissection, 5-μm-thick tissue sections were cut from the FFPE whole-mount pancreatic tissue block, mounted on standard glass slides, and heated for 60 min at 60°C. Slides were stored at 27°C until use.

Experimental workflow

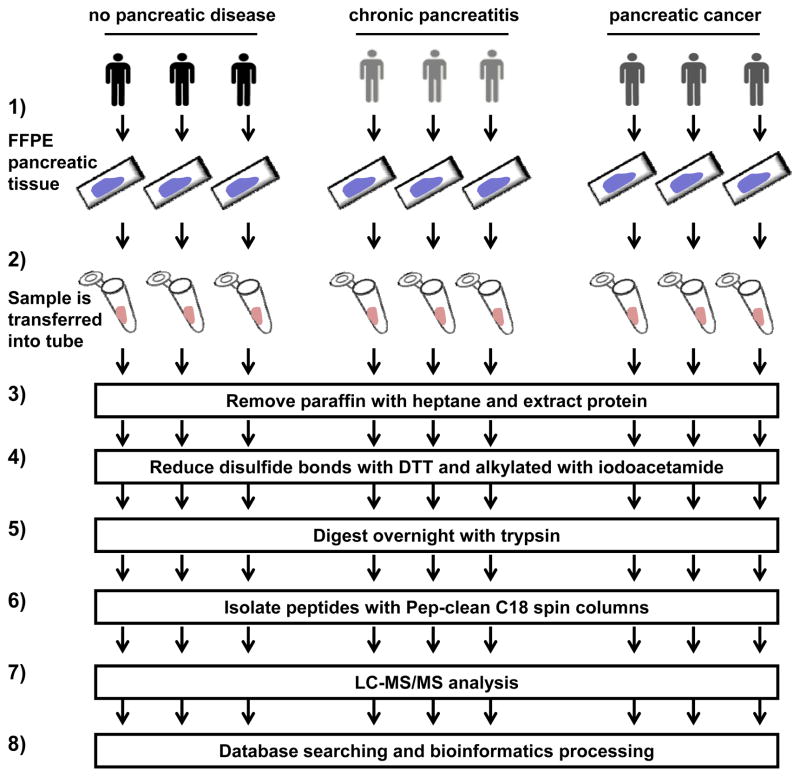

The overall experimental analysis was shown in Figure 1: 1) FFPE tissue specimens were obtained from the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center research pathology core, 2) a 1.5 cm × 1 cm × 5 μm slice of the FFPE tissue was scraped into a microcentrifuge tube, 3) paraffin was removed with heptane, 4) disulfide bonds were reduced with dithiotreitol (DTT) and alkylated with iodoacetamide, 5) sample was digested overnight with trypsin, 6) peptides were isolated with Pep-clean C18 spin columns, 7) LC-MS/MS analysis was carried out, and 8) data was searched against a protein database after which bioinformatics processing was performed.

Figure 1. Experimental workflow.

1) FFPE tissue specimens were obtained, 2) a 1.5 cm × 1 cm × 5 μm slice of sample was scraped into a tube, 3) paraffin was removed with heptane, 4) disulfide bonds were reduced with dithiotreitol (DTT) and alkylated with iodoacetamide, 5) sample was digested overnight with trypsin, 6) peptides were isolated, 7) LC-MS/MS analysis was performed, and 8) bioinformatics analysis was performed.

Sample preparation for mass spectrometry analysis

The sample preparation protocol for mass spectrometry analysis was assembled from several sources 15, 17–20. After removing the excess paraffin, a 1.5 cm × 1 cm square of the 5 μm thick FFPE pancreatic tissue specimen from each glass slide was scraped using a clean razor blade into a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube. To remove the remaining paraffin, 0.5 mL heptane was added to each sample, followed by vigorous vortexing for 10 seconds and incubation at room temperature for 1 h. After the incubation, 25 μL of methanol was added to each tube, followed by vigorous vortexing for 10 seconds and centrifugation (20,000 g for 2 min at 4°C). Immediately following centrifugation, the upper (heptane) layer was discarded and the lower layer was allowed to evaporate. To extract proteins from this mixture, the dried material was resuspended in 250 μL 6M guanidine-HCl/50 mM ammonium bicarbonate/20 mM DTT, pH 8.5, briefly sonicated, and incubated at 70°C for 1 h. After cooling, iodoacetamide was added to a final concentration of 40 mM and the sample was incubated at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. The alkylation reaction was quenched by adding 3 μL of 2 M DTT. For tryptic digestion, the sample was diluted 1:6 with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 8.1 to reduce the concentration of guanidine-HCl to 1 M. Each sample was incubated with 2.5 μg of trypsin. Following the incubation, the reaction was acidified with formic acid to a final concentration of 0.1% and evaporated by vacuum centrifugation. To remove interfering substances prior to mass spectrometry, peptides were isolated with Pep-clean C18 spin columns using manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were vacuum centrifuged to dryness and stored at −80°C until analysis. Immediately prior to analysis, the peptides were resuspended in sample loading buffer (5% formic acid, 5% acetonitrile, 90% water).

Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry analysis was performed at the Proteomics Center at Children’s Hospital Boston. The resuspended peptides were subjected to peptide fractionation using reversed-phase high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC; Thermo Scientific) and the gradient-eluted peptides were analyzed using an LTQ FT Ultra mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The liquid chromatography columns (15 cm × 100 μm ID) were packed in-house with Magic C18 (5 μm, 100 Å, Michrom BioResources, Auburn, CA), into PicoTips (New Objective, Woburn, MA). Samples were analyzed with a 90 min linear gradient (0–35% acetonitrile with 0.2% formic acid) and data were acquired in a data-dependent manner, in which MS/MS fragmentation was performed on the six most intense peaks of every full MS scan.

Bioinformatics and data analysis

All data generated from the gel sections were searched against the international protein index (IPI) human database (v3.61) using the Paragon Algorithm 21, which is integrated into the ProteinPilot search engine (v.3; AB SCIEX, Foster City, CA). Search parameters were set as follows: sample type, identification; Cys alkylation, iodoacetamide; Instrument, Orbitrap/FT (1–3 ppm); special factors, none; ID focus, none; database, IPI- human (v.3.61); detection protein threshold, 99.0%; and search effort, thorough ID. Thus, using our stringent criteria, we defined an identified protein as one with ≥99% confidence, as determined by the Paragon Algorithm 21. For purpose of comparative proteome investigation, a protein was required to have been identified in 2 of 3 specimens of a particular cohort.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis

GO analysis 22 was performed using the GoFact online tool 23, 24 and verified manually using data from the UniProt 25 database. Annotation categories used were as follows: functions: enzyme regulator activity, ion binding, kinase activity, lipid binding, nucleic acid binding, nucleotide binding, oxygen binding, peptidase activity, protein binding, signal transducer activity, structural molecule activity, transcription regulator activity, and transporter activity; cellular component: cytoskeleton, cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), endosome, extracellular matrix, extracellular region, golgi apparatus, lysosomes, membrane, mitochondrion, nucleus, ribonucleoprotein complex, and vacuole.

KEGG pathway analysis

Using the DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) Bioinformatics Database (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) interface 26, 27, we analyzed our protein lists with KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway analysis28–30.

Results

Proteomic analysis of FFPE tissue identified several hundred proteins using mass spectrometry-based proteomic techniques

FFPE tissue from nine histologically-classified archived specimens [no pancreatic disease (n=3), chronic pancreatitis (n=3) and pancreatic cancer (n=3)] were subjected to mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis, as is depicted in Figure 1. For the analysis of each specimen, we used a single slice of FFPE tissue with dimensions of 1.5 cm × 1 cm × 5 μm. Mass spectrometric analysis of all 9 FFPE specimens identified a total 525 non-redundant proteins, which we list in Supplementary Table 1. A non-redundant protein is one that has been counted only once, regardless of the number of specimens in which it has been identified.

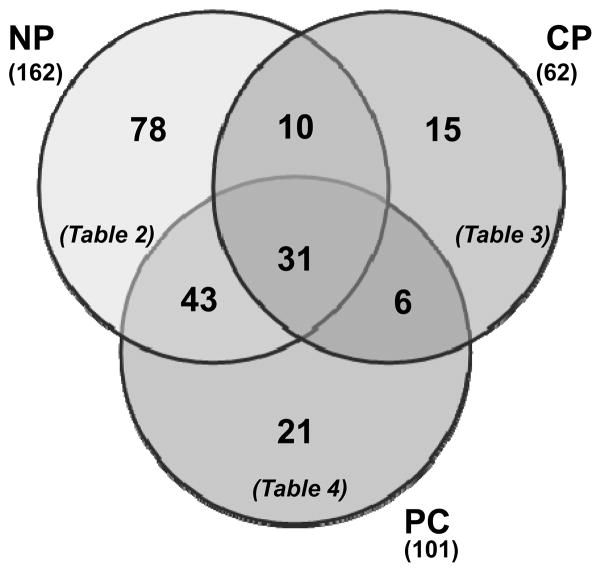

Of the proteins identified, some proteins were exclusive to a particular cohort

Table 1 summarizes the number of non-redundant proteins identified in this study. Taking each specimen individually, we identified 266, 102, and 199 non-redundant proteins in each normal pancreas (NP) specimen. Similarly, we identified 82, 98, and 85 non-redundant proteins in each chronic pancreatitis (CP) specimen. Likewise, we identified 130, 183, and 134 non-redundant proteins in each pancreatic cancer (PC) specimen. We then merged the three protein lists for each cohort to determine the number of non-redundant proteins identified within each cohort, as listed in Table 1. After merging these lists, the numbers of non-redundant proteins were: 312 in normal pancreas, 162 in chronic pancreatitis, and 178 pancreatic cancer. To minimize false positives, we tightened our analysis criteria by using a filtering strategy which included only proteins that were identified in 2 of 3 specimens. This filtering reduced the number of identified non-redundant proteins to 162 in normal pancreas, 62 in chronic pancreatitis, and 101 pancreatic cancer.

Table 1.

Summary of the number of proteins identified from FFPE tissue specimens by cohort.

| cohort | specimen # | number of non-redundant identified proteins

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total* | within each cohort | in 2 of 3 specimens | exclusive to each cohort | ||

| NP | 1 | 266 | 312 | 162 | 78 |

| 2 | 102 | ||||

| 3 | 199 | ||||

| CP | 1 | 82 | 162 | 62 | 15 |

| 2 | 98 | ||||

| 3 | 85 | ||||

| PC | 1 | 130 | 178 | 101 | 21 |

| 2 | 183 | ||||

| 3 | 134 | ||||

Abbreviations: NP, normal pancreas; CP, chronic pancreatitis; PC, pancreatic cancer.

A total of 525 non-redundant proteins were identified in the study.

We determined the proteins that were exclusive to each cohort, in other words, proteins that appeared exclusively in one particular cohort and neither of the other cohorts. Thus, we identified 78 proteins in normal pancreas (Table 2), 15 proteins in chronic pancreatitis (Table 3), and 21 proteins in pancreatic cancer (Table 4) specimens which were exclusive to each particular cohort. These values were visualized by a Venn diagram in Figure 2. Among those proteins identified exclusively in the normal pancreas specimens include: carboxypeptidase B, carboxy ester lipase 2, retinal dehydrogenase 1, and spink1. Similarly, collagen α1 (XIV), collagen α3 (VI), filamin A, and SNC73 were identified exclusively in the chronic pancreatitis specimens. In addition, annexin 4A and fibronectin were among the proteins that were identified exclusively in the pancreatic cancer specimens.

Table 2.

Proteins (78) identified in at 2 of 3 normal pancreas specimens and not in the other two cohorts, as illustrated in the Venn diagram in Figure 2. The number of peptides (#pep) identified and the sequence coverage (%cov) of each protein are indicated.

| Name | IPI # | NP1 | NP2 | NP3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #pep | %cov | #pep | %cov | #pep | %cov | ||

| 19 kDa protein | IPI00795717 | 5 | 59.4 | 3 | 45.5 | ||

| 21 kDa protein | IPI00478208 | 4 | 43.5 | 3 | 46.2 | ||

| ACTN4 actinin-4 | IPI00013808 | 3 | 13.8 | 2 | 9.8 | ||

| ADH1B cDNA FLJ51682, similar to Alcohol dehydrogenase 1B | IPI00872991 | 1 | 10.8 | 2 | 14.6 | ||

| AGRN Agrin | IPI00374563 * | 2 | 15.6 | 1 | 5.8 | 2 | 7.3 |

| ALDH1A1 Retinal dehydrogenase 1 | IPI00218914 | 3 | 20.2 | 4 | 16.6 | ||

| ANXA4 annexin IV | IPI00793199 | 12 | 40.5 | 8 | 40.8 | ||

| ATP1A1 Na+/K+-ATPase α1 subunit isoform d | IPI00930085 | 4 | 10.3 | 2 | 6.8 | ||

| cDNA FLJ50378, Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase αchain | IPI00909657 | 2 | 11.1 | 2 | 15.1 | ||

| cDNA FLJ56074, 150 kDa oxygen-regulated protein | IPI00922838 | 2 | 15.1 | 1 | 10.9 | ||

| cDNA FLJ60461, similar to Peroxiredoxin-2 | IPI00909207 | 3 | 28.4 | 3 | 31.7 | ||

| CEL carboxyl ester lipase (bile salt-stimulated lipase) isoform 2 | IPI00936498 | 9 | 28.6 | 3 | 13.8 | ||

| CELA3B 33 kDa protein | IPI00871512 | 2 | 10.7 | 6 | 33.6 | ||

| CKAP4 Isoform 1 of Cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 | IPI00141318 | 3 | 16.8 | 3 | 22.1 | ||

| CLTC Isoform 2 of Clathrin heavy chain 1 | IPI00455383 | 3 | 10.6 | 2 | 7.6 | ||

| CPB1 Carboxypeptidase B | IPI00009826 | 6 | 40.5 | 6 | 33.3 | ||

| DCN Isoform A of Decorin | IPI00012119 * | 3 | 30.9 | 6 | 24.5 | 1 | 29 |

| DDT 14 kDa protein | IPI00878984 | 3 | 24.2 | 3 | 39.4 | ||

| FGG 50 kDa protein | IPI00877792 | 1 | 22.9 | 3 | 19.1 | ||

| GDI2 GDP dissociation inhibitor 2 isoform 2 | IPI00640006 | 2 | 18.8 | 2 | 32 | ||

| GP2 cDNA, FLJ92575, glycoprotein 2, (GP2) | IPI00937053 | 2 | 17.2 | 6 | 14.5 | ||

| HIST2H2AC Histone H2A type 2-C | IPI00339274 | 9 | 78.3 | 5 | 58.1 | ||

| HNRNPA1 A1-A of nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 | IPI00465365 | 3 | 24.4 | 3 | 29.4 | ||

| HSPA8 Isoform 1 of Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | IPI00003865 | 6 | 30.3 | 5 | 13.8 | ||

| HSPB6 Heat shock protein β6 | IPI00022433 | 2 | 29.1 | 1 | 21.1 | ||

| HSPD1 60 kDa heat shock protein | IPI00784154 | 11 | 31.9 | 3 | 20.1 | ||

| IGHA1 cDNA, similar to Ig α1 chain C region | IPI00449920 | 3 | 37.9 | 4 | 35.9 | ||

| INS;INS-IGF2;IGF2 Insulin | IPI00001508 | 12 | 76.4 | 3 | 75.5 | ||

| LAMA2 Putative uncharacterized protein LAMA2 | IPI00873889 | 3 | 6.4 | 1 | 7.1 | ||

| LAMA5 Laminin subunit α5 | IPI00783665 | 4 | 8.3 | 2 | 6.4 | ||

| LMNA Isoform A of Lamin-A/C | IPI00021405 | 3 | 19.6 | 3 | 13.7 | ||

| LRRC47 Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 47 | IPI00170935 | 2 | 9.9 | 2 | 7.4 | ||

| MDH2 cDNA FLJ52880, Malate dehydrogenase | IPI00924593 | 7 | 50.3 | 1 | 15.5 | ||

| MYL6 cDNA FLJ56329, similar to Myosin light polypeptide 6 | IPI00796366 | 3 | 36.6 | 4 | 27.3 | ||

| PARK7 Protein DJ-1 | IPI00298547 | 3 | 48.2 | 1 | 33.3 | ||

| PEBP1 Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 | IPI00219446 | 2 | 50.3 | 2 | 50.8 | ||

| PHGDH D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | IPI00011200 | 6 | 38.5 | 4 | 26.5 | ||

| PKM2 Isoform M1 of Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 | IPI00220644 | 6 | 29.9 | 4 | 35.2 | ||

| PRDX4 Peroxiredoxin-4 | IPI00011937 | 4 | 24.7 | 3 | 17.7 | ||

| PRELP Prolargin | IPI00020987 | 3 | 18.1 | 2 | 21.7 | ||

| PRSS1 PRSS1 protein | IPI00815665 | 15 | 33.6 | 20 | 33.6 | ||

| RCTPI1;TPI1 Isoform 1 of Triosephosphate isomerase | IPI00797270 * | 9 | 52.2 | 2 | 45.8 | 6 | 46.6 |

| REG1B Lithostathine-1-beta | IPI00009197 | 14 | 49.4 | 1 | 13.9 | ||

| RPL10A 60S ribosomal protein L10a | IPI00412579 | 2 | 27.7 | 2 | 22.1 | ||

| RPL18A 60S ribosomal protein L18a | IPI00026202 | 5 | 61.4 | 6 | 56.3 | ||

| RPL21P16;RPL21P19;RPL21 60S ribosomal protein L21 | IPI00247583 | 9 | 63.1 | 5 | 62.5 | ||

| RPL23 Similar to ribosomal protein L23 | IPI00795408 | 7 | 53.6 | 6 | 55.7 | ||

| RPL26 60S ribosomal protein L26 | IPI00027270 | 3 | 37.9 | 2 | 32.4 | ||

| RPL3 60S ribosomal protein L3 | IPI00550021 | 6 | 34 | 5 | 31.3 | ||

| RPL30 Putative uncharacterized protein RPL30 | IPI00872940 | 3 | 67.8 | 1 | 28.7 | ||

| RPL35A 60S ribosomal protein L35a | IPI00029731 | 3 | 84.6 | 4 | 41.8 | ||

| RPL36 60S ribosomal protein L36 | IPI00216237 | 4 | 51.4 | 3 | 44.8 | ||

| RPL37A 60S ribosomal protein L37a | IPI00414860 | 2 | 69.6 | 4 | 66.3 | ||

| RPL38 8 kDa protein | IPI00792410 | 3 | 22.4 | 4 | 50.8 | ||

| RPL4 cDNA FLJ50996, similar to 60S ribosomal protein L4 | IPI00795303 | 4 | 41.6 | 11 | 69.3 | ||

| RPL7A 60S ribosomal protein L7a | IPI00299573 | 8 | 54.1 | 6 | 47 | ||

| RPN1 Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide--protein glycosyltransferase | IPI00025874 | 4 | 12.7 | 5 | 13.2 | ||

| RPS10P29 similar to ribosomal protein S10 | IPI00398673 | 2 | 25.7 | 2 | 36.3 | ||

| RPS12 40S ribosomal protein S12 | IPI00013917 | 7 | 45.5 | 3 | 27.3 | ||

| RPS15 40S ribosomal protein S15 | IPI00479058 | 4 | 51 | 1 | 16.6 | ||

| RPS18 40S ribosomal protein S18 | IPI00013296 | 4 | 54.6 | 4 | 30.9 | ||

| RPS28 40S ribosomal protein S28 | IPI00719622 | 5 | 56.5 | 3 | 69.6 | ||

| RPS3 40S ribosomal protein S3 | IPI00011253 | 3 | 23.9 | 4 | 32.1 | ||

| RPS3A 40S ribosomal protein S3a | IPI00419880 | 5 | 47.7 | 2 | 22.4 | ||

| RPS5 40S ribosomal protein S5 | IPI00008433 | 4 | 48.5 | 5 | 34.8 | ||

| RPS7P10 similar to mCG19129 | IPI00887413 | 3 | 33 | 2 | 43.5 | ||

| SERPINB1 Leukocyte elastase inhibitor | IPI00027444 | 2 | 8.4 | 6 | 23.8 | ||

| SFPQ Isoform Long of Splicing factor, proline- and glutamine-rich | IPI00010740 | 2 | 23.6 | 1 | 9.8 | ||

| SNORA67;EIF4A1 46 kDa protein | IPI00871852 | 2 | 21.9 | 1 | 16.5 | ||

| SPINK1 Pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor | IPI00020687 | 1 | 43 | 2 | 60.8 | ||

| SPR Sepiapterin reductase | IPI00017469 | 1 | 17.6 | 1 | 15.3 | ||

| SSR4 Protein | IPI00646864 | 1 | 13.3 | 2 | 20.8 | ||

| TUBA1B Tubulin α1B chain | IPI00930688 | 4 | 19.5 | 2 | 17.1 | ||

| TUBB2C Tubulin β2C chain | IPI00007752 | 7 | 27.6 | 7 | 31 | ||

| UBA1 Ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme 1 | IPI00645078 | 5 | 14.6 | 2 | 12.3 | ||

| VTN Vitronectin | IPI00298971 | 3 | 10.3 | 1 | 19.9 | ||

| YWHAB Isoform Long of 14-3-3 protein beta/alpha | IPI00216318 | 4 | 35.8 | 4 | 27.2 | ||

| YWHAE cDNA FLJ51975, moderately similar to 14-3-3 protein epsilon | IPI00795516 | 3 | 44.9 | 3 | 24.3 | ||

Abbreviations: NP, normal pancreas; CP, chronic pancreatitis; PC, pancreatic cancer.

denotes proteins appearing in all 3 specimens.

Table 3.

Proteins (15) identified in 2 of 3 chronic pancreatitis specimens and not in the other two cohorts, as illustrated in the Venn diagram in Figure 2. The number of peptides (#pep) identified and the sequence coverage (%cov) of each protein are indicated.

| Name | IPI # | CP1 | CP2 | CP3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #pep | %cov | #pep | %cov | #pep | %cov | ||

| cDNA FLJ60058, similar to Myosin light chain 1 | IPI00909366 | 2 | 15.7 | 2 | 36.8 | ||

| COL14A1 Isoform 2 of Collagen α1(XIV) | IPI00550918 | 2 | 12.8 | 2 | 10.8 | ||

| COL6A3 Isoform 1 of Collagen α3(VI) | IPI00022200 | 3 | 15.4 | 6 | 18 | 8 | 27.3 |

| DEFA1;LOC728358 Neutrophil defensin 1 | IPI00005721 * | 4 | 34 | 7 | 36.2 | 3 | 67 |

| FLNA Isoform 1 of Filamin-A | IPI00333541 | 10 | 26.5 | 33 | 39.1 | ||

| HIST2H2BF histone cluster 2, H2bf isoform b | IPI00930174 * | 9 | 87.3 | 8 | 84.3 | 12 | 93.3 |

| HNRNPA1, nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 | IPI00909288 | 3 | 66.1 | 2 | 41.7 | ||

| IGHA1 cDNA FLJ14473 fis, SNC73 protein (SNC73) mRNA | IPI00386879 | 11 | 36.8 | 2 | 22.9 | ||

| IGK@ IGK@ protein | IPI00784985 | 1 | 28.5 | 6 | 48.5 | ||

| LMNA Progerin | IPI00644087 * | 1 | 12.9 | 3 | 13.5 | 5 | 23.3 |

| MFAP2 microfibrillar-associated protein 2 isoform b | IPI00644827 | 2 | 17 | 1 | 18.1 | ||

| PFN1 Profilin-1 | IPI00216691 | 2 | 44.3 | 2 | 49.3 | ||

| PKM2 Pyruvate kinase | IPI00909560 | 6 | 39.9 | 2 | 27.4 | ||

| RNASE3 Eosinophil cationic protein | IPI00025427 | 2 | 37.5 | 2 | 48.1 | ||

| RPS8 Ribosomal protein S8 | IPI00645201 | 2 | 30.9 | 2 | 39.9 | ||

Abbreviations: NP, normal pancreas; CP, chronic pancreatitis; PC, pancreatic cancer.

denotes proteins appearing in all 3 specimens.

Table 4.

Proteins (21) identified in 2 of 3 pancreatic cancer specimens and not in the other two cohorts, as illustrated in the Venn diagram in Figure 2. The number of peptides (#pep) and sequence coverage (%cov) identified in each specimen are indicated for each protein.

| Name | IPI # | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #pep | %cov | #pep | %cov | #pep | %cov | ||

| ANXA4 Annexin A4 | IPI00872780 | 7 | 40.4 | 3 | 22.3 | ||

| CALM3;CALM1;CALM2 cDNA, FLJ96792, similar to calmodulin 2 | IPI00916768 | 2 | 32.9 | 1 | 18.1 | ||

| COL1A2 Collagen α2(I) chain | IPI00304962 | 7 | 25.9 | 8 | 27.8 | ||

| FN1 fibronectin 1 isoform 2 preproprotein | IPI00845263 | 14 | 18.4 | 5 | 13.9 | ||

| HBD;HBB Hemoglobin subunit delta | IPI00473011 * | 10 | 73.5 | 12 | 75.5 | 12 | 78.9 |

| HIST1H1C Histone H1.2 | IPI00217465 | 12 | 51.6 | 16 | 67.1 | ||

| HNRNPA2B1 Putative uncharacterized protein HNRNPA2B1 | IPI00916517 * | 3 | 34.1 | 4 | 46.1 | 2 | 45.1 |

| HNRNPM Isoform 2 of nuclear ribonucleoprotein M | IPI00383296 | 5 | 28.1 | 2 | 37.5 | ||

| LOC100292021 similar to thioredoxin peroxidase | IPI00938009 | 4 | 29.6 | 2 | 28.8 | ||

| LYZ Lysozyme C | IPI00019038 | 3 | 24.3 | 1 | 16.2 | ||

| MYH9 Isoform 1 of Myosin-9 | IPI00019502 | 1 | 12.5 | 1 | 16.3 | ||

| RPL14 60S ribosomal protein L14 | IPI00925323 | 1 | 23.9 | 2 | 38 | ||

| RPL15;RPL15P3 Ribosomal protein L15 | IPI00550032 | 5 | 62.3 | 4 | 50.5 | ||

| RPL21P119 hypothetical protein isoform 1 | IPI00887074 * | 3 | 42.5 | 5 | 46.9 | 3 | 34.4 |

| RPL23 10 kDa protein | IPI00795751 * | 3 | 86.8 | 9 | 71.4 | 3 | 81.3 |

| RPL24 60S ribosomal protein L24 | IPI00306332 | 1 | 30.6 | 5 | 63.7 | ||

| RPL4 60S ribosomal protein L4 | IPI00003918 * | 4 | 43.3 | 16 | 64.4 | 8 | 54.6 |

| RPS7 40S ribosomal protein S7 | IPI00013415 | 1 | 26.8 | 5 | 36.1 | ||

| TKT cDNA FLJ54957, similar to Transketolase | IPI00643920 | 5 | 28.5 | 1 | 15.9 | ||

| VCL Isoform 2 of Vinculin | IPI00307162 | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 6.3 | ||

| YWHAB Isoform Short of 14-3-3 protein beta/alpha | IPI00759832 | 3 | 32.4 | 2 | 14.8 | ||

Abbreviations: NP, normal pancreas; CP, chronic pancreatitis; PC, pancreatic cancer.

denotes proteins appearing in all 3 specimens.

Figure 2. Overlap of proteins among the three cohorts.

Venn diagrams showing unique and overlapping proteins among the three cohorts. Also indicated in the figure are the tables in which these sets of proteins are listed. Abbreviations: NP, normal pancreas; CP, chronic pancreatitis; PC, pancreatic cancer.

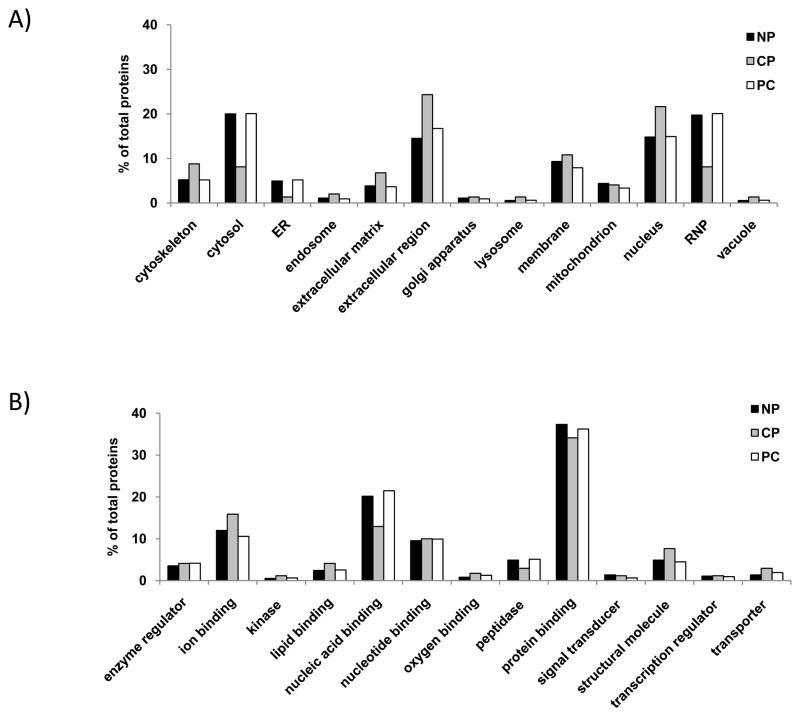

Gene ontology (GO) analysis among the proteins identified from each cohort revealed moderate differences

As an initial investigation of the proteins which we have identified in FFPE tissue, we examined the subcellular localization (Figure 3A) and molecular function (Figure 3B) of the proteins in each of the three cohorts. For this analysis, we used the total proteins identified in each specimen (312 for normal, 162 for chronic pancreatitis and 178 for pancreatic cancer). In terms of subcellular localization, normal and pancreatic cancer specimens were similar, however there were striking differences with the chronic pancreatitis cohort. The chronic pancreatitis cohort had a 1.5-fold or greater number of proteins classified as cytoskeletal, or originating from the extracellular matrix, extracellular region (secreted), or nucleus. Conversely, there was a 1.5-fold or lower number of proteins which are cytosolic, originate from endoplasmic reticulum or are ribonucleic proteins when compared to the other two cohorts. Similarly, when examining the molecular functions of the proteins that we identified, there was a 1.5-fold or greater increase in the number of structural and transporter proteins, and a 1.5-fold or lower number of proteins involved in nucleic acid binding or proteolysis when comparing the chronic pancreatitis specimens with those from the other two cohorts.

Figure 3. Gene ontology annotation.

A) Subcellular localization. B) Molecular function. We include in this analysis all non-redundant proteins that were identified in each cohort. Abbreviations: NP, normal pancreas; CP, chronic pancreatitis; PC, pancreatic cancer.

KEGG pathway analysis

As a preliminary analysis of the biomolecular pathways in which the proteins we have identified in FFPE tissue were involved, we examined the proteins exclusive to each of the three cohorts using KEGG pathway analysis. Our data revealed that several proteins appearing exclusively in the normal pancreas specimens were involved in ECM-receptor interactions. These proteins included agrin, laminin α2, laminin α5, and vitronectin. In addition, there were several proteins involved in ribosomal function. In the chronic pancreatitis specimens, KEGG analysis revealed that collagen type IV α3 and filamin A were involved in the focal adhesion pathway. In pancreatic cancer specimens, KEGG analysis revealed involvement in the regulation of actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesion. The proteins involved in regulation of actin cytoskeleton included fibronectin 1, myosin 9, viculin, and actin gamma 1; and those involved in focal adhesions included actin gamma 1, collagen type I α2, vinculin, and fibronectin 1.

Supplementary data

We included several supplementary tables listing the identified proteins. The 525 non-redundant proteins from the 9 specimens were listed in Supplementary Table 1 including those identified only in one specimen. We also included several tables listing proteins which overlap between two cohorts. Supplementary Table 2 lists the 10 non-redundant proteins which were determined to be in common between normal and chronic pancreatitis. Supplementary Table 3 lists the 43 non-redundant proteins in common between normal and pancreatic cancer. Supplementary Table 4 lists the 6 non-redundant proteins in common between chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. In the tables, the percent protein coverage (%cov) and number of identified peptides (#pep) were listed. The percent coverage referred to the percentage of amino acid residues of a particular protein that was present in identified peptides for that particular protein. The number of peptides referred to the number of non-redundant peptides that were used to identify that particular protein. Supplementary Table 5 lists the proteins appearing in 2 of 3 specimens of every cohort. Ten proteins appeared in all nine FFPE specimens, these are: Fibrillin-1, hemoglobulin subunits α and β, histone H11.4, histone H4, heat shock protein β1, trypsin-1, ribosomal protein L19, peptidylpropyl isomerase A-like protein, and vimentin. Such consistently-identified proteins can serve to define a core set of proteins that are identified from FFPE pancreatic tissues.

Discussion

We have successfully applied LC-MS/MS analysis to FFPE tissue. In total, we have identified 525 non-redundant proteins among all 9 specimens. We used a filtering strategy that required a protein to appear in 2 of 3 specimens to be included in subsequent analyses. By comparing these proteins, we have identified those that were found exclusively in normal (78), chronic pancreatitis (15), and pancreatic cancer (21). The FFPE tissue processing techniques and mass spectrometry strategies which we perform herein with pancreatic tissue have been used previously to study tissues of other organ systems, including prostate 31, cochlea19, liver 18,32, glioblastoma 33, renal carcinoma 34, kidney glomeruli 35, mesenchymal tissue 17, and B-cell lymphoma cells 36. A previously published study analyzed pancreatic cancer FFPE tissue using a Liquid Tissue workflow for a global proteomics analysis 16. We, however, present the first comparative LC-MS/MS analysis of FFPE tissue from a wide spectrum of pancreatic disease that included: normal, chronic pancreatitis, and pancreatic cancer FFPE tissue.

Our mass spectrometry-based analysis revealed several proteins which are excusive to specimens from particular cohorts. Below, we select several proteins which may merit further investigation to verify their role in pancreatic cancer or chronic pancreatitis. Proteins identified exclusively in the normal pancreas specimens (Table 2) include: Carboxypeptidase B, carboxy ester lipase 2, retinal dehydrogenase 1, and spink1. Carboxypeptidase B and carboxy ester lipase 2 are common pancreatic enzymes, and are expected to be present in healthy pancreata 37. Retinal dehydrogenase 1 binds free retinal and cellular retinol-binding protein-bound retinal and converts retinaldehyde to retinoic acid, thus having a role in vitamin A metabolism 38. Coincidently loss of stored cytoplasmic vitamin A is related to pancreatic stellate cell activation and fibrosis associated with chronic pancreatitis 39. Spink 1 is a pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor which prevents the trypsin-catalyzed premature activation of zymogens within the pancreas. Defects in the gene encoding the spink 1 protein has been widely studied in pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer 40–43. In addition to the abundance of proteins involved with pancreatic enzymes, KEGG pathway analysis revealed proteins, agrin, laminin α2, laminin α5, and vitronectin, found exclusively in the normal specimens as having roles in extracellular matrix receptor interactions. Such interactions may be essential in the turnover of extracellular matrix, a process which is impaired in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer patients.

Selected proteins of interest identified exclusively in the chronic pancreatitis specimens (Table 3) include: Collagen α1 (XIV), collagen α3 (VI), filamin A, and SNC73. Collagen α1 (XIV), a putative structural molecule that associates with collagen fibrils, may be involved in the rearrangement of connective tissue. Similarly, collagen α3 (VI) is an extracellular matrix structural constituent involved in the TGF-β receptor signaling pathway, which is implicated in pancreatic fibrosis. Also, filamin A, acts in actin cytoskeleton organization and apoptosis, regulates cell migration and plays a role in disrupting the cellular cytoskeleton 44. SNC73, a protein that shares homology with immunoglobulins, has been found to be a potential biomarker of colorectal cancer 45. These secreted or extracellular matrix proteins may have roles in the inflammatory cascade that is thought to lead to pancreatic fibrosis 46, 47. Similarly, KEGG pathway analysis has identified extracellular proteins, collagen type I α2 and filamin A, which are involved in focal adhesions, and may have an analogous role in pancreatic cancer development.

Selected proteins of interest identified exclusively in pancreatic cancer (Table 4) include: annexin 4A and fibronectin. Annexin A4 is a calcium/phospholipid-binding protein which promotes membrane fusion and is involved in exocytosis. In the pancreas, this protein has a role in binding zymogen granules, which may have implications in proper proenzyme export from the pancreas 48–50. Another structural protein, fibronectin binds cell surfaces and various compounds including collagen, fibrin, heparin, DNA, and actin 51. The inhibition of fibronectin-dependent proliferation has recently been shown to have antitumor effects 52. In addition, annexin A5 and 14-3-3zeta were identified in both chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer specimens (Supplementary Table 3). Both annexin A5 53, 54 and 14-3-3zeta 49 have been associated with pancreatic cancer in previously published proteomic studies. Also, annexin A5 has been found by DNA microarrays to be a biomarker of pancreatic cancer 55. In addition, we have determined using KEGG pathway analysis that proteins in pancreatic cancer specimens, fibronectin 1, myosin 9, viculin, collagen type I α2, vinculin, fibronectin 1, and actin gamma 1, were mapped to focal adhesion and/or actin cytoskeletal pathways. Studies have shown an integral link between focal adhesion and/or actin cytoskeletal proteins and pancreatic cancer 56–60. Further biochemical studies, such as western blotting or immunoprecipitation must be performed to analyze further the identified proteins in terms of their GO annotations and KEGG pathways.

Although we were able to identify a total of 525 proteins, harsh FFPE tissue preparation conditions presents a barrier which limits proteomic protein identification. Additionally, there is an inherent difficulty in extracting intact proteins from FFPE tissue due to protein crosslinking that is associated with specimen preparation. Chemically, during tissue fixation, formalin adds a methylene hydrate group to the side chain of certain amino acids leading to a methylene bridge formation that results in protein crosslinking 61, 62. Although modifications are common on side chain moieties of lysyl, arginyl, tyrosyl, histidyl and seryl 63, all 20 amino acids have been successfully identified during LC-MS/MS analysis of peptides originating from FFPE tissue with frequencies similar to that in frozen tissue 18, 32. However, formalin-induced intra- and intermolecular crosslinking hinders the solubility of proteins, often complicating the extraction of proteins, and potentially larger peptides, from FFPE specimens 64. In fact, harsh formalin fixation (greater than 96 hours) has been shown to result in DNA fragmentation and enhanced protein crosslinks which have adverse effects on genomic and proteomic investigations 65. Analogously, in transcriptomics analysis, the extraction of mRNA is also significantly reduced as a result of extensive periods of fixation 66. Future improvements in the methods of sample analysis may overcome these difficulties, which would greatly increase the depth of the proteomic analysis of preserved historical FFPE specimens.

Fresh frozen tissue presents an alternative specimen preservation strategy for proteomic analyses. However, frozen tissue is difficult to store and requires liquid nitrogen or ultra-low temperature (−80°C) freezer storage. In contrast to frozen specimens, FFPE specimens are generally processed with standard methodologies and are inherently stable at room temperature. Unlike FFPE tissue, fresh-frozen tissue has been shown to not properly maintain its morphology 63, 67. Furthermore, other recent studies in tissues from follicular lymphoma 15, ear canal 19, renal carcinoma 34, colon and breast cancer 68, and liver20, have identified nearly as many, or even more proteins using FFPE tissue than frozen tissue. A recent study by Ostasiewicz, et al., has shown that not only is the proteome preserved in FFPE mouse liver tissue, but so are the posttranslational modifications of phosphorylation and N-glycosylation 32. Although several studies have compared proteins identified from fresh-frozen and FFPE tissue specimens, no such comparison has been performed using pancreatic tissue. While there may be proteolytic enzymes in previously-studied tissues, pancreatic tissue has a higher propensity of self-digestion as a result of endogenous proteases. A systematic study of a statistically significant number of FFPE and frozen pancreatic tissue is needed to further assess the benefits of one method over the other for mass spectrometry-based proteomic analyses. As such, assaying the benefits of modifications to current strategies, including, but not limited to, the addition of protease inhibitors, fixation at lower temperatures, and meticulous handling of tissue on ice, may allow for a greater depth of proteomic analysis from FFPE tissue of pancreatic origin.

As with other mass spectrometry-based proteomics studies, sample complexity may limit the analytical depth of any proteomic study. Many recent studies have used various forms of fractionation to minimize the complexity of the proteome in the FFPE tissue specimen under investigation, which may increase the number of identified proteins. In general, decreases in protein complexity can be achieved by fractionation at the peptide, protein, subcellular, or cellular level prior to mass spectrometric analysis. In our previous studies, we have investigated pancreatic and gastroduodenal fluid using GeLC-MS/MS techniques, which fractionates by electrophoretic mobility 11, 69, 70. Although protein level fractionation may be thought of as impractical for FFPE tissue, as intermolecular crosslinking can impair protein extraction and mobility during fractionation, several research groups have recently been successful in SDS-PAGE analysis of whole proteins extracted from FFPE tissues 34, 68, 71, 72. Alternatively, commonly-used methods of peptide fractionation include various forms of liquid chromatography and separation by isoelectric points 73. More recently, a novel sample preparation strategy, FASP (Filter Aided Sample Preparation) has been developed and used successfully to analyze samples which are difficult to process including membrane proteins and FFPE tissue specimens 74, 75, 32. FFPE tissue fractionation can also be performed at the cellular level with the isolation of specific cell types or regions of tissue, as was previously done for pancreatic cancer tissue analysis 16. Similar to tissue biopsies, FFPE sections generally consist of different cell types. If the aim is to target only particular cell types, serial sectioning and laser-capture microdissection (LCM) is suitable for such analyses 76,77, 35. Such cellular fractionation by microdissection decreases sample complexity and thus increases analytical depth. In terms of future investigations of FFPE pancreatic tissue, it may be practical to utilize a similar methodology to enrich for regions rich in ductal or acinar cells via microdissection.

A major advantage of pursuing the proteomic investigation of FFPE tissue is the availability of a vast archive of patient samples with clearly defined patient histories and well-documented diagnoses. Such specimens are an invaluable resource for translational studies, enabling the analysis of pancreatic tissue specimens from patients with known outcomes. The value of these tissues is not limited to biomarker discovery, but also may result in a better understanding of the molecular processes and pathways that lead to end-stage disease. In addition, the use of proteomics for FFPE tissue analysis allows for correlation of these data with miRNA and/or mRNA studies that use FFPE tissue 78–81. Challenges which must be addressed, however, include the establishment of more efficient protein or peptide extraction and the assessment of potential modifications of the amino acid residues resulting from specimen preparation.

In summary, we have shown that mass spectrometry-based FFPE tissue analysis is applicable to the study of pancreatic tissue. Our results indicate that differentially-expressed proteins can be identified among FFPE tissues specimens originating from individuals with normal pancreata, chronic pancreatitis, and pancreatic cancer. With further methodological optimization, LC-MS/MS-based proteomic analysis of FFPE pancreatic tissue specimens may provide novel protein targets for improved therapy or a means of high-throughput validation of current biomarkers. Given the vast availability of FFPE specimens, large databases of diseased and normal tissue-specific proteins may be assembled for validation via orthogonal methodologies, such as immunohistochemistry studies. The work which we present herein demonstrates the potential use of LC-MS/MS for the analysis of archived FFPE pancreatic tissue and provides a basis upon which biomarker studies can be developed.

Supplementary Material

Total proteins, 525, identified in all FFPE tissues (including those identified in only one specimen. The number of peptides (#pep) and sequence coverage (%cov) for each protein identified in each specimen are indicated and organized by cohort.

Proteins (10) identified in 2 of 3 specimens of both normal and chronic pancreatitis specimens and not in pancreatic cancer specimens, as illustrated in the Venn diagram in Figure 2. The number of peptides (#pep) identified and the sequence coverage (%cov) of each protein are indicated.

Proteins (43) identified in 2 of 3 specimens of both normal and pancreatic cancer specimens and not in chronic pancreatitis specimens, as illustrated in the Venn diagram in Figure 2. The number of peptides (#pep) identified and the sequence coverage (%cov) of each protein are indicated.

Proteins (6) identified in 2 of 3 specimens of both chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer specimens and not in the normal pancreas specimens, as illustrated in the Venn diagram in Figure 2. The number of peptides (#pep) identified and the sequence coverage (%cov) of each protein are indicated.

Proteins (31) identified in 2 of 3 specimens of every cohort, as illustrated in the Venn diagram in Figure 2. The number of peptides (#pep) identified of each protein is indicated.

Acknowledgments

Funds were provided by the following NIH grants: 1 F32 DK085835-01A1) (JP), 1 R21 DK081703-01A2 (DC) and 5 P30 DK034854-24 (Harvard Digestive Diseases Center; DC). In addition, we would like to thank the Burrill family for their generous support through the Burrill Research Grant. We would also like to thank members of the Steen Lab at Children’s Hospital Boston, in particular John FK Sauld and Dominic Winter, as well as Kate Repas (Research Manager) from the Center for Pancreatic Disease at Brigham and Women’s Hospital for their technical assistance and critical reading of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- CP

chronic pancreatitis

- FFPE

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- GO

gene ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Gene and Genomes

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry

- LCM

laser capture microdissection

- NP

normal pancreas

- PC

pancreatic cancer

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JP carried out the experiments and drafted the original manuscript. JP and DC conceived of the study. JP, DC, and HS participated in its design and coordination. All authors assisted drafting the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Joao A. Paulo, Department of Pathology, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA. Proteomics Center at Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA. Center for Pancreatic Disease, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Linda S. Lee, Center for Pancreatic Disease, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Peter A. Banks, Center for Pancreatic Disease, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Hanno Steen, Department of Pathology, Children’s Hospital Boston and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA Proteomics Center at Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA.

Darwin L. Conwell, Center for Pancreatic Disease, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.NIH. NIH publ no 08-6514. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2009. Opportunities and Challenges in Digestive Diseases Research: Recommendations of the National Commission on Digestive Diseases; pp. 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thongboonkerd V. Proteomics of human body fluids : principles, methods, and applications. Humana Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decramer S, Gonzalez de Peredo A, Breuil B, Mischak H, Monsarrat B, Bascands JL, Schanstra JP. Urine in clinical proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:1850–62. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R800001-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Good DM, Thongboonkerd V, Novak J, Bascands JL, Schanstra JP, Coon JJ, Dominiczak A, Mischak H. Body fluid proteomics for biomarker discovery: lessons from the past hold the key to success in the future. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:4549–55. doi: 10.1021/pr070529w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paik YK, Kim H, Lee EY, Kwon MS, Cho SY. Overview and introduction to clinical proteomics. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;428:1–31. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-117-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barratt J, Topham P. Urine proteomics: the present and future of measuring urinary protein components in disease. Cmaj. 2007;177:361–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hortin GL, Sviridov D. Diagnostic potential for urinary proteomics. Pharmacogenomics. 2007;8:237–55. doi: 10.2217/14622416.8.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller H, Brenner H. Urine markers as possible tools for prostate cancer screening: review of performance characteristics and practicality. Clin Chem. 2006;52:562–73. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.062919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munro NP, Cairns DA, Clarke P, Rogers M, Stanley AJ, Barrett JH, Harnden P, Thompson D, Eardley I, Banks RE, Knowles MA. Urinary biomarker profiling in transitional cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2642–50. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thongboonkerd V. Urinary proteomics: towards biomarker discovery, diagnostics and prognostics. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:810–5. doi: 10.1039/b802534g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulo JA, Lee LS, Wu B, Repas K, Banks PA, Steen H, Conwell D. Cytokine protein microarray analysis of pancreatic fluid in tandem with the endoscopic pancreatic function test (ePFT) Pancreatology. 2010 Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tammen H. Specimen collection and handling: standardization of blood sample collection. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;428:35–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-117-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi SR, Cote RJ, Taylor CR. Antigen retrieval techniques: current perspectives. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:931–7. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steen H, Mann M. The ABC’s (and XYZ’s) of peptide sequencing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:699–711. doi: 10.1038/nrm1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reimel BA, Pan S, May DH, Shaffer SA, Goodlett DR, McIntosh MW, Yerian LM, Bronner MP, Chen R, Brentnall TA. Proteomics on Fixed Tissue Specimens - A Review. Curr Proteomics. 2009;6:63–69. doi: 10.2174/157016409787847420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung W, Darfler MM, Alvarez H, Hood BL, Conrads TP, Habbe N, Krizman DB, Mollenhauer J, Feldmann G, Maitra A. Application of a global proteomic approach to archival precursor lesions: deleted in malignant brain tumors 1 and tissue transglutaminase 2 are upregulated in pancreatic cancer precursors. Pancreatology : official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology. 2008;8:608–16. doi: 10.1159/000161012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balgley BM, Guo T, Zhao K, Fang X, Tavassoli FA, Lee CS. Evaluation of archival time on shotgun proteomics of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:917–25. doi: 10.1021/pr800503u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang X, Feng S, Tian R, Ye M, Zou H. Development of efficient protein extraction methods for shotgun proteome analysis of formalin-fixed tissues. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1038–47. doi: 10.1021/pr0605318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer-Toy DE, Krastins B, Sarracino DA, Nadol JB, Jr, Merchant SN. Efficient method for the proteomic analysis of fixed and embedded tissues. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:2404–11. doi: 10.1021/pr050208p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu H, Yang L, Wang W, Shi SR, Liu C, Liu Y, Fang X, Taylor CR, Lee CS, Balgley BM. Antigen retrieval for proteomic characterization of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1098–108. doi: 10.1021/pr7006768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shilov IV, Seymour SL, Patel AA, Loboda A, Tang WH, Keating SP, Hunter CL, Nuwaysir LM, Schaeffer DA. The Paragon Algorithm, a next generation search engine that uses sequence temperature values and feature probabilities to identify peptides from tandem mass spectra. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1638–55. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T600050-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li D, Li JQ, Ouyang SG, Wu SF, Wang J, Xu XJ, Zhu YP, He FC. An integrated strategy for functional analysis in large-scale proteomic research by gene ontology. Progress in Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2005;32:1026–1029. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong L, Jianqi L, Shuguang O, Songfeng W, Jian W, Yunping Z, Fuchu H. An integrated strategy for functional analysis in large scale proteomic research by gene ontology. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2005;4:S34–S34. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bairoch A, Apweiler R, Wu CH, Barker WC, Boeckmann B, Ferro S, Gasteiger E, Huang H, Lopez R, Magrane M, Martin MJ, Natale DA, O’Donovan C, Redaschi N, Yeh L-SL. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucl Acids Res. 2005;33:D154–159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogata H, Goto S, Sato K, Fujibuchi W, Bono H, Kanehisa M. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:29–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wixon J, Kell D. The Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes--KEGG. Yeast. 2000;17:48–55. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(200004)17:1<48::AID-YEA2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hood BL, Darfler MM, Guiel TG, Furusato B, Lucas DA, Ringeisen BR, Sesterhenn IA, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Krizman DB. Proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed prostate cancer tissue. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1741–53. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500102-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostasiewicz P, Zielinska DF, Mann M, Wisniewski JR. Proteome, Phosphoproteome, and N-Glycoproteome Are Quantitatively Preserved in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tissue and Analyzable by High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2010 doi: 10.1021/pr100234w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo T, Wang W, Rudnick PA, Song T, Li J, Zhuang Z, Weil RJ, DeVoe DL, Lee CS, Balgley BM. Proteome analysis of microdissected formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55:763–72. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7177.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi SR, Liu C, Balgley BM, Lee C, Taylor CR. Protein extraction from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections: quality evaluation by mass spectrometry. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:739–43. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5B6851.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waanders LF, Chwalek K, Monetti M, Kumar C, Lammert E, Mann M. Quantitative proteomic analysis of single pancreatic islets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18902–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908351106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crockett DK, Lin Z, Vaughn CP, Lim MS, Elenitoba-Johnson KS. Identification of proteins from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded cells by LC-MS/MS. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1405–15. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beck IT. The role of pancreatic enzymes in digestion. Am J Clin Nutr. 1973;26:311–25. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/26.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gagnon I, Duester G, Bhat PV. Enzymatic characterization of recombinant mouse retinal dehydrogenase type 1. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:1685–90. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madro A, Celinski K, Slomka M. The role of pancreatic stellate cells and cytokines in the development of chronic pancreatitis. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:RA166–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kereszturi E, Kiraly O, Sahin-Toth M. Minigene analysis of intronic variants in common SPINK1 haplotypes associated with chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2009;58:545–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.164947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hucl T, Jesnowski R, Pfutzer RH, Elsasser HP, Lohr M. SPINK1 variants in young-onset pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:599. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keim V. Mutations of the SPINK1 gene and their relation to chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2005;5:311. doi: 10.1159/000086529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsubayashi H, Fukushima N, Sato N, Brune K, Canto M, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, Kern SE, Goggins M. Polymorphisms of SPINK1 N34S and CFTR in patients with sporadic and familial pancreatic cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:652–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li C, Yu S, Nakamura F, Yin S, Xu J, Petrolla AA, Singh N, Tartakoff A, Abbott DW, Xin W, Sy MS. Binding of pro-prion to filamin A disrupts cytoskeleton and correlates with poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2725–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI39542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geng LY, Shi ZZ, Dong Q, Cai XH, Zhang YM, Cao W, Peng JP, Fang YM, Zheng L, Zheng S. Expression of SNC73, a transcript of the immunoglobulin alpha-1 gene, in human epithelial carcinomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2305–11. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i16.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mews P, Phillips P, Fahmy R, Korsten M, Pirola R, Wilson J, Apte M. Pancreatic stellate cells respond to inflammatory cytokines: potential role in chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2002;50:535–41. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masamune A, Watanabe T, Kikuta K, Shimosegawa T. Roles of pancreatic stellate cells in pancreatic inflammation and fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:S48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sitek B, Sipos B, Alkatout I, Poschmann G, Stephan C, Schulenborg T, Marcus K, Luttges J, Dittert DD, Baretton G, Schmiegel W, Hahn SA, Kloppel G, Meyer HE, Stuhler K. Analysis of the Pancreatic Tumor Progression by a Quantitative Proteomic Approach and Immunhistochemical Validation. J Proteome Res. 2009 doi: 10.1021/pr800890j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen J, Person MD, Zhu J, Abbruzzese JL, Li D. Protein expression profiles in pancreatic adenocarcinoma compared with normal pancreatic tissue and tissue affected by pancreatitis as detected by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9018–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fukuoka S, Kern H, Kazuki-Sugino R, Ikeda Y. Cloning and characterization of ZAP36, an annexin-like, zymogen granule membrane associated protein, in exocrine pancreas. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1575:148–52. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yi M, Ruoslahti E. A fibronectin fragment inhibits tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:620–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwarz RE, Awasthi N, Konduri S, Caldwell L, Cafasso D, Schwarz MA. Antitumor effects of EMAP II against pancreatic cancer through inhibition of fibronectin-dependent proliferation. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010:9. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.8.11265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cui Y, Zhang D, Jia Q, Li T, Zhang W, Han J. Proteomic and tissue array profiling identifies elevated hypoxia-regulated proteins in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:747–55. doi: 10.1080/07357900802672746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mulla A, Christian HC, Solito E, Mendoza N, Morris JF, Buckingham JC. Expression, subcellular localization and phosphorylation status of annexins 1 and 5 in human pituitary adenomas and a growth hormone-secreting carcinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;60:107–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Maitra A, Olsen M, Lowe AW, van Heek NT, Rosty C, Walter K, Sato N, Parker A, Ashfaq R, Jaffee E, Ryu B, Jones J, Eshleman JR, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Kern SE, Hruban RH, Brown PO, Goggins M. Exploration of global gene expression patterns in pancreatic adenocarcinoma using cDNA microarrays. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1151–62. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63911-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chatzizacharias NA, Giaginis C, Zizi-Serbetzoglou D, Kouraklis GP, Karatzas G, Theocharis SE. Evaluation of the clinical significance of focal adhesion kinase and SRC expression in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 39:930–6. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181d7abcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duxbury MS, Ito H, Ashley SW, Whang EE. CEACAM6 cross-linking induces caveolin-1-dependent, Src-mediated focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation in BxPC3 pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23176–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duxbury MS, Ito H, Benoit E, Zinner MJ, Ashley SW, Whang EE. RNA interference targeting focal adhesion kinase enhances pancreatic adenocarcinoma gemcitabine chemosensitivity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311:786–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Furuyama K, Doi R, Mori T, Toyoda E, Ito D, Kami K, Koizumi M, Kida A, Kawaguchi Y, Fujimoto K. Clinical significance of focal adhesion kinase in resectable pancreatic cancer. World J Surg. 2006;30:219–26. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0165-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kiehne K, Herzig KH, Folsch UR. Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton by p125 focal adhesion kinase in rat pancreatic acinar cells. Digestion. 1999;60:153–60. doi: 10.1159/000007641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rait VK, Xu L, O’Leary TJ, Mason JT. Modeling formalin fixation and antigen retrieval with bovine pancreatic RNase A II. Interrelationship of cross-linking, immunoreactivity, and heat treatment. Lab Invest. 2004;84:300–6. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rait VK, O’Leary TJ, Mason JT. Modeling formalin fixation and antigen retrieval with bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A: I-structural and functional alterations. Lab Invest. 2004;84:292–9. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fox CH, Johnson FB, Whiting J, Roller PP. Formaldehyde fixation. J Histochem Cytochem. 1985;33:845–53. doi: 10.1177/33.8.3894502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahram M, Flaig MJ, Gillespie JW, Duray PH, Linehan WM, Ornstein DK, Niu S, Zhao Y, Petricoin EF, 3rd, Emmert-Buck MR. Evaluation of ethanol-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues for proteomic applications. Proteomics. 2003;3:413–21. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200390056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Romero RL, Juston AC, Ballantyne J, Henry BE. The applicability of formalin-fixed and formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissues in forensic DNA analysis. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42:708–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benchekroun M, DeGraw J, Gao J, Sun L, von Boguslawsky K, Leminen A, Andersson LC, Heiskala M. Impact of fixative on recovery of mRNA from paraffin-embedded tissue. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2004;13:116–25. doi: 10.1097/00019606-200406000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McKenna RJ, Jr, Houck WV. New approaches to the minimally invasive treatment of lung cancer. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:282–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000166589.08880.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Becker KF, Schott C, Hipp S, Metzger V, Porschewski P, Beck R, Nährig J, Becker I, Höfler H. Quantitative protein analysis from formalin-fixed tissues: implications for translational clinical research and nanoscale molecular diagnosis. The Journal of Pathology. 2007;211:370–378. doi: 10.1002/path.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paulo J, Lee LS, Banks PA, Steen H, Conwell D. Proteomic analysis of endoscopically (ePFT) collected gastroduodenal fluid using in-gel tryptic digestion followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Proteomics - Clinical Applications. 2010 doi: 10.1002/prca.201000018. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paulo JA, Lee LS, Wu B, Repas K, Mortele KJ, Banks PA, Steen H, Conwell DL. Identification of Pancreas-Specific Proteins in Endoscopically (Endoscopic Pancreatic Function Test) Collected Pancreatic Fluid with Liquid Chromatography- Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Pancreas. 2010 doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181cf16f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grantzdorffer I, Yumlu S, Gioeva Z, von Wasielewski R, Ebert MP, Rocken C. Comparison of different tissue sampling methods for protein extraction from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. Exp Mol Pathol. 2010;88:190–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scicchitano MS, Dalmas DA, Boyce RW, Thomas HC, Frazier KS. Protein extraction of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue enables robust proteomic profiles by mass spectrometry. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:849–60. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.953497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fritz JS, Gjerde DT. Ion chromatography. Wiley-VCH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wisniewski JR, Zougman A, Mann M. Combination of FASP and StageTip-based fractionation allows in-depth analysis of the hippocampal membrane proteome. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:5674–8. doi: 10.1021/pr900748n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wisniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Methods. 2009;6:359–62. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Emmert-Buck MR, Bonner RF, Smith PD, Chuaqui RF, Zhuang Z, Goldstein SR, Weiss RA, Liotta LA. Laser capture microdissection. Science. 1996;274:998–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Patel V, Hood BL, Molinolo AA, Lee NH, Conrads TP, Braisted JC, Krizman DB, Veenstra TD, Gutkind JS. Proteomic analysis of laser-captured paraffin-embedded tissues: a molecular portrait of head and neck cancer progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1002–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nonn L, Vaishnav A, Gallagher L, Gann PH. mRNA and micro-RNA expression analysis in laser-capture microdissected prostate biopsies: valuable tool for risk assessment and prevention trials. Exp Mol Pathol. 2010;88:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ikenaga N, Ohuchida K, Mizumoto K, Yu J, Fujita H, Nakata K, Ueda J, Sato N, Nagai E, Tanaka M. S100A4 mRNA is a diagnostic and prognostic marker in pancreatic carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1852–8. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0978-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu A, Tetzlaff MT, Vanbelle P, Elder D, Feldman M, Tobias JW, Sepulveda AR, Xu X. MicroRNA expression profiling outperforms mRNA expression profiling in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;2:519–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gjerdrum LM, Abrahamsen HN, Villegas B, Sorensen BS, Schmidt H, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ. The influence of immunohistochemistry on mRNA recovery from microdissected frozen and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2004;13:224–33. doi: 10.1097/01.pdm.0000134779.45353.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Total proteins, 525, identified in all FFPE tissues (including those identified in only one specimen. The number of peptides (#pep) and sequence coverage (%cov) for each protein identified in each specimen are indicated and organized by cohort.

Proteins (10) identified in 2 of 3 specimens of both normal and chronic pancreatitis specimens and not in pancreatic cancer specimens, as illustrated in the Venn diagram in Figure 2. The number of peptides (#pep) identified and the sequence coverage (%cov) of each protein are indicated.

Proteins (43) identified in 2 of 3 specimens of both normal and pancreatic cancer specimens and not in chronic pancreatitis specimens, as illustrated in the Venn diagram in Figure 2. The number of peptides (#pep) identified and the sequence coverage (%cov) of each protein are indicated.

Proteins (6) identified in 2 of 3 specimens of both chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer specimens and not in the normal pancreas specimens, as illustrated in the Venn diagram in Figure 2. The number of peptides (#pep) identified and the sequence coverage (%cov) of each protein are indicated.

Proteins (31) identified in 2 of 3 specimens of every cohort, as illustrated in the Venn diagram in Figure 2. The number of peptides (#pep) identified of each protein is indicated.