Abstract

Rates of sexual assault of college students are higher than the national rates. Colleges are uniquely positioned to offer preventive education and support services to a high-risk group. This qualitative study examines students’ perceptions of sexual violence resources and services. Seventy-eight female and male students, between 18–24 years old, belonging to various demographic groups participated in one-to-one, walking interviews on five diverse Midwest 2- and 4-year postsecondary campuses. Findings suggest that students are concerned with safety, students want more education regarding sexual violence, and they value services that offer protection from incidents of sexual violence on campus. Participants expressed mixed reactions to prevention education that combined sexual violence prevention with alcohol and drug use. Students shared positive views of the security measures on campus. They emphasized the importance of using varied mechanisms for sexual violence-related resource messaging and advised moving away from the pamphlet towards posters and online resources. Recommendations are offered to strengthen existing resources, such as prevention education and post-assault interventions including Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) services, and to minimize barriers to access of sexual violence resources.

Keywords: sexual violence, prevention, college-age, young adult, interview, go-along

Introduction

In the unique social context of a college setting, students strive to increase their knowledge and obtain credentials that will effectively position them as future workforce members. The pursuit of education is only one common attribute of college students. Primarily between 18 and 24 years of age, undergraduate college students are also characterized by qualities of late adolescence, including high levels of peer group affiliation, challenging the status quo, exploring their world via experimentation and, at times, risk-taking behaviors (Arnett, 2000; Barry, Madsen, Nelson, Carroll & Badger, 2009; ACHA, 2010).

A college campus provides opportunity to create life-long relationships, although for some students it also presents risky and at times dangerous situations. In a survey of 13,700 students at the University of Minnesota, 15.9% reported experiencing a sexual assault within their lifetime (Boynton Health Service, 2010). Sexual violence is a critical, relatively common occurrence (Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher & Martin, 2009) that can yield long-lasting ramifications for the victim (Kaltman, Krupnick, Stockton, Hooper, & Green, 2005), yet sexual assault frequently goes unreported. In the same University of Minnesota study, only one-third (32.3%) of the college students who experienced sexual assault reported the incident to any official at all, including the police (Boynton Health Service, 2010), which is a rate consistent with documented trends (Amar & Gennaro, 2005; Fisher et al., 2003; Rennison, 2002). Those who reported the assault most often did so to a health care provider (27.5%), a police officer (21.4%), or a campus hall director, community advisor, or sexual violence officer/security officer (7.1%) (Boynton Health Service, 2010). It is possible students’ perceptions of the college environment, and specifically resources available for post-sexual assault care, directly influence decisions whether to report the incident and to whom to make the report. Certainly a supportive environment can encourage early help-seeking and reporting following a sexual assault (Clements & Ogle, 2009).

Researchers have documented a variety of individual, interpersonal, and socio-cultural factors associated with post-assault help-seeking behaviors and perceptions (Amar, 2008; Amar, Bess, & Stockbridge, 2010; Fisher, Daigle, Cullen, & Turner, 2003). The college environment, specifically the presence or absence of sexual violence awareness campaigns and resources, is the context in which a student who has experienced sexual violence will determine initially whether and how s/he will report or seek care. To our knowledge male and female students’ perceptions of environmental (e.g. college) sexual violence-related resources remain unexamined. This is important because willingness to seek care might be enhanced or hindered by perceptions about the accessibility, availability and awareness of resources on campus (Banyard et al., 2007; Walsh, Banyard, Moynihan, Ward, & Cohn, 2010), or by the perception of support or shaming by healthcare professionals (Hanson, 2010; Messman-Moore, Coates, Gaffey, & Johnson, 2008; Nasta et al., 2005). In the absence of inter-personal or socio-cultural barriers to help-seeking, negative perception of college environment and available resources might be the deciding obstacle to seeking care.

The extent to which a college environment is conducive to reporting sexual violence incidents, and seeking follow-up care, could influence short- and long-term recovery for a student victim. In addition to the well-documented psychological consequences of silently and independently surviving sexual violence (Avant, Swopes, Davis, & Elhai, 2010; Danielson et al., 2010), a student victim might choose to leave college and forego educational pursuits (Grossman, Haney, Edwards, Alessi, Ardon, & Howell, 2009) thereby impacting future career opportunities, goal-setting, and one’s sense of accomplishment (Stepakoff, 1998; Tschumper, Narring, Meier, & Michaud, 1998).

Consistent with national public health priorities as identified in Healthy People 2020 (Department of Health and Human Services, 2010), reduction and prevention of sexual violence experienced by college students is critical. To accomplish national improvements among young adults, who experience disproportionate rates of sexual violence, will require careful attention toward college environments because these are the primary contexts in which violence occurs and care is sought.

Conceptual underpinnings

An ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) facilitates examination of contextual factors unique to sexual violence prevention for college students. Specifically, the college environment is one of the primary micro-systems surrounding students during their years of study. This college setting can be a source of risk, protection, or both. Risks might include interpersonal and environmental exposures (i.e., substance use in a dorm, limited light posts) and protections can similarly exist at an interpersonal or environmental level within the micro-system (i.e., resident hall advisor, adequate security personnel, sexual violence prevention campaigns). Certainly, individual and socio-cultural level factors contribute significantly to one’s sense of vulnerability in addition to one’s willingness to seek help following an incident, as has been well described (Amar et al., 2010; Ashley & Foshee, 2005; Bauer, Rodriguez, Quiroga, & Flores-Ortiz, 2000). To our knowledge there has not been a study examining the college micro-system specifically with respect to college students’ perceptions of sexual violence prevention resources. Therefore, the purpose of this research was to describe male and female students’ perceptions of their college’s sexual violence prevention resources and efforts.

Study Aim

Because sexual violence can be experienced by anyone, and subsequently any college student could someday be in need of accessing sexual violence resources either for themselves or on behalf of another, it is important to gain understanding from a general college student population, including males and females, rather than solely seeking perceptions of those who have previously experienced sexual violence (Porter & McQuiller-Williams, 2011). Therefore, the aim of this study is to gain a broad understanding regarding college campus sexual violence resources that will yield unique insights colleges can use to inform the development of strategic interventions that minimize barriers and enhance access to sexual violence resources.

Methods

This study used a go-along interview qualitative design. Go-along interviews offer a unique opportunity to gain first-hand contextualized insights (Carpiano, 2009; Jones, 2008; Kusenbach, 2003). During a go-along interview, the participant physically and virtually leads the interviewer on a tour as the interview occurs.

Research setting

The participating institutions represented the diversity of post-secondary education options in one Midwestern state, including metropolitan and non-metropolitan two-year and four-year institutions that were both public and private. Each participant guided the interviewer through a walking and online virtual tour of campus sexual health resources. Only one participant was reluctant to walk through campus, for an undisclosed reason, so his interview was conducted in a private office.

Sample

The target population for this study was undergraduate male and female college students aged 18 to 24. Between 12 and 18 participants were recruited from each of 5 colleges, reflecting diverse characteristics (e.g., ethnicity, extracurricular involvement). To be eligible for participation, students must not have been employed by, nor volunteered for, campus health services; this criterion enabled us to obtain perspectives from typical students rather than those with exceptional insights into college health services. Participants did not need to have any prior experience using college sexual health services, nor any knowledge specific to sexual health or sexual health resources. All study procedures were conducted after receiving approval from all relevant institutional review boards.

Data collection procedures

Student recruitment occurred in a high-traffic area on each campus, using purposive and snowball sampling strategies. A wait-list approach was used to ensure approximately 50% female participants and diversity of ethnicity as well as year in school (Porter & McQuiller-Williams, 2011). Interested students were screened by the study staff for eligibility and scheduled for an interview. Participants completed the consent process at the time of the interview, filled out a demographic form, and received a $50 retail store gift card as a token of appreciation.

Three researchers conducted the walk-along interviews, including a professor and two graduate assistants. Each graduate assistant received instruction on conducting the go-along interviews and shadowed on at least one interview. Interviews took place on weekdays when existing campus health service offices were open during spring, summer, and fall semesters in 2010. The interviews lasted an average of 48 minutes (ranging 24–88 minutes).

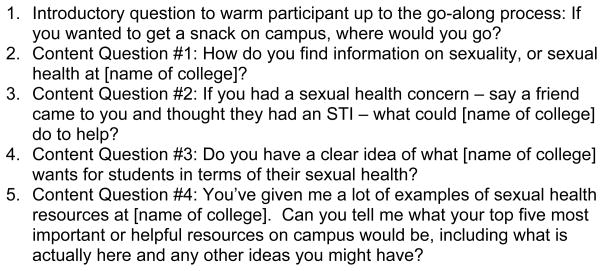

A semi-structured interview guide was used, which included an introductory warm-up question and four content questions regarding sexual health resources available on or near campus (see Figure 1); the questions did not pertain specifically to sexual violence (Author et al, under review a). Sexual violence-related resources, or the lack thereof, were one of the most commonly identified resources, mentioned by 60% of the participants (Author et al, under review b); the present study reports on those comments and perspectives.

Figure 1.

Interview Guide

Data management

The go-along interviews were audio-recorded with a lapel microphone attached to the participant. Upon completion of each interview the interviewer verified the complete recording and saved the audio file to a secure server. The audio files were transcribed by professional transcriptionists and verified by study staff by simultaneously listening to and reading the interview. ATLAS.ti software (Muhr, 2010) was used to organize the transcripts and facilitate the coding process.

Data analysis

Text from each interview was carefully read through multiple times by the research team. Initial thematic codes were generated for a codebook based on the primary study aims; a quasi-inductive coding process was used so that new ideas could be descriptively represented by codes (Saldaña, 2009). Two graduate students, led by the qualitative co-investigator, independently coded the text. The first few coded interviews were carefully examined and discussed among the research team to ensure agreement in the codes used to describe text.

All codes with potential content addressing sexual violence prevention were included in this analysis. From these codes, 252 quotes from 60 participants were obtained. In addition, all interview text was examined for possible sexual violence prevention content that was not originally coded.

Descriptive categories were created to organize the codes. For example, an identified resource might be a “Safe Walk Home” program, where a member of the security personnel will meet a student to walk them to a dorm from the library late at night; the text would be coded as ‘resource: safe escort service’ to designate the specific descriptive code for a sexual violence prevention resource identified by the student, and the category of the resource. Simultaneous coding facilitated identifying multiple codes or ideas within one section of text, enabling thorough representation of the interview text (Saldaña, 2009).

Two participants who provided consent to be contacted at a later date independently reviewed the summary of sexual violence data presented in this manuscript; member checks are important mechanisms for ensuring that data are being presented in a representative manner (Sandelowski, 1993), which both participants confirmed.

Results

Participant Demographics

The final sample, 78 participants including thirty-eight women (49%) and forty men (51%), was comprised of 32 students from two-year institutions (41%) and 46 students from four-year institutions (59%). The average age of participants was 20 years (range 18–24). Fifty-two (67%) participants identified as white and twenty-six (33%) as individuals of color, including self-identified multi-racial and Hispanic students. Participants represented a broad range of student characteristics and communities, including dorm residents, commuters, transfer students, first year and advanced students, the gay-lesbian-bisexual-transgender (GLBT) community, the Greek community, the military, athletes, pregnant and/or parenting students, those who identified themselves as sexually active, and those who identified themselves as having never been sexually active.

Overview of findings

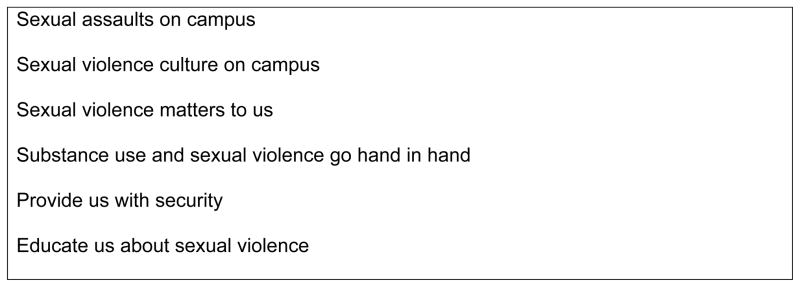

Our coding and reflective, iterative analysis process yielded six themes regarding sexual violence prevention on campus: 1) sexual assaults on campus, 2) sexual violence culture on campus, 3) sexual violence matters to us, 4) substance use and sexual violence go hand in hand, 5) provide us with security, and 6) educate us about sexual violence (see Figure 2). These themes are described in detail below, with supportive participant quotes (represented by pseudonyms).

Figure 2.

Themes regarding sexual violence prevention on campus:

Sexual assaults on campus

Participants from every campus expressed concerns regarding sexual violence and incidents that occurred on or near campus. Elaine, a student who appeared well informed about sexual violence resources and what to do if something happened, shared a specific incident involving her friend:

Last fall I had a friend finally admit to me, she had been really upset for a while and I just asked her what was going on. It was not a usual thing for her. She did finally say somebody attacked her and raped her. She was a virgin. The first thing I thought of was, ‘have you told anybody yet?’ She hadn’t. I knew that she hadn’t had a rape kit done. I knew that she hadn’t gone to a doctor at all. The next thing that came to mind was just her mental health, her emotional health, as well as pregnancy and STDs. Obviously she doesn’t have birth control or anything. I did ask her if she wanted me to help her with those things…she really didn’t want to talk to anybody, but she did have issues sleeping. She was super afraid to go home at night.

In addition to Elaine, two other students mentioned SANE services as a post-assault resource, and something victims should seek out.

Andrea indicated that her campus was safe, compared to other campuses, despite sharing two vivid sexual violence incidents:

…one of my friends…said that he gave her some candy and started trying to take off her clothes. That would definitely be a problem, but I think it more has to do with if you are drinking than anything else. I heard stories too of last year, or I don’t know which year it was, a girl was out jogging and some guy came out. It was dark, late at night, and she had her headphones in and couldn’t hear. Some guy came up behind her, hit her upside the head with a bat and raped her.

Sexual violence culture on campus

The campus culture with regards to sexual violence was discussed by many students and reflected diversity of perspectives. For example, for some students, the campus culture had to do with organizational openness in terms of addressing the topic of sexual violence; for others, the culture was about the climate, feeling safe. And for yet others, the culture included students’ behaviors in terms of reporting or not reporting an incident. In response to a hypothetical question about seeking care for a friend, Ibrahim summarized his sense of the campus culture with respect to sexual violence:

The culture about that [sexual assault] here is a lot less open than regular sexual health stuff. There have been a good number of instances where people I know have thought that it’s happened, but have been too afraid to report it.

Conner described a campus-sponsored educational offering in which the speaker countered the culture of blaming sexual violence victims by challenging students to reflect on how cultural views on men and women get perpetuated and need to be stopped, such as in the example of athleticism where males are praised for their skills while females are often recognized for other attributes first (e.g., physical appearance). Regarding the event, he said:

It is well done and it doesn’t really have the statistics around rape, as much as it highlights the environment that we encourage by making jokes about women athletes and how our society promotes this culture. If a girl is raped, what do we say about her? We say, ‘where was she?’ Our immediate reaction isn’t even sympathy. The immediate reaction is what was she doing when she got raped? Was she wearing skimpy clothes down a dark alley? Did she go to a party and get too drunk? She kind of asked for it, didn’t she? We are already justifying the guy after he violated the girl.

Another element of campus culture arose in comments about the physical size of the school, and the student body. Marlin felt his campus offered a safe physical atmosphere:

It feels safe around here because of the people. Just because nobody goes out of their way to make you feel uncomfortable. Everybody just does their own thing. We are a smaller school, so you do see a lot of familiar faces. You build trust with a lot of different people that you might not actually hang out with but you see them enough…

Sexual violence matters to us

When asked to identify the most important sexual health resources a college can have, over half the students identified sexual violence resources as a priority. Connor stated, “they need some type of response to sexual violence.” Peter affirmed, “I guess the STD testing [as first priority], and then I’d go with sexual assault and rape.” On this particular campus, a large public institution, attention toward and prioritization of rape-related resources appeared to be in part related to three rape incidents that had received media attention in the weeks preceding the interviews. Seth shared,

…especially the rape thing, because a month ago we had three girls raped in the [fraternity house part of campus], so if you had resources for students who happen to get sexually assaulted that would be nice because they’re kind of hidden around here.

Substance use and sexual violence go hand in hand

Substance use was described by numerous participants as they discussed aspects of sexual violence on campus. Georgina linked alcohol and sexual activity together when she identified what she thought was the biggest sexual health issue faced by students, “probably sex under the influence would be a big one.” Trevor, a military student, recommended action to prevent alcohol-facilitated sexual assaults, “Maybe someone should get out there and explain to students about alcohol-related issues and drinking, so problems like what happened on [campus name] wouldn’t ever happen here.” Georgina pointed out a campus effort to bring attention to this issue, “I’ve seen posters around that say, ‘no means no, and if there is alcohol involved yes means no too.’ Stuff like that. They focus on when alcohol is involved.” She felt the college was sending a clear message regarding sexual health and alcohol use, “I definitely remember in freshman orientation talking about the alcohol and they hope that we don’t drink and then have sex.”

At another institution, Katrina described a campus-sponsored event in which sexual violence was “touched on” in the context of substance use,

It [sexual violence] was touched on because I did go to one of the [event name] that was about alcoholism and drugs, and they touched on, then there’s rape. It was almost a direct result, where it should be its own entity, instead of…It was almost like, ‘OK, you drink, you’re going to get raped.’ It’s like, I don’t really agree with that. I walk home from my clinicals and I live in a very rough neighborhood, so it could happen to me in my whites. That would really, really suck, but I wasn’t drinking and I wasn’t being dumb and I wasn’t wearing provocative clothing, just all this… That’s where a lot of people get that stigma…Not that anything on this topic is warm and fuzzy, but it should be discussed outside of drinking and drugs.

Although alcohol use was the most commonly reported substance by participants from numerous campuses, the mention of ‘roofies’ or drugs facilitating sexual assault only occurred among participants from one campus. Charity described what happened to her,

I know there are a lot of party houses that you’re supposed to avoid because they roofie people. I got roofied last year; thank God my [female] friends took care of me. It [being roofied] was by my own [male] friends, so I just don’t go out. Obviously, he [was] my friend so I’m going to trust him, but I ended up in the hospital. They said, ‘there’s no alcohol in your system; it’s just [rohynpnol] so I owed them three thousand dollars. Now I don’t go to parties anymore.

Ibrahim, a student from the same campus, commented on roofies and rumors, There’s huge rumors around [campus name] about roofies being used. It kind of goes away and resurges every few months. That one, as far as I know, is just hearsay, nothing substantial to it because of the amount of alcohol availability.

Although it was very rare, two students did speak about personal responsibility regarding prevention of sexual violence through responsible choices about alcohol, with a blaming tone to their voices. Dominique said, “Well, you’ve probably heard about all the rapes on campus. I don’t think it’s…I mean if you’re smart, you won’t be in that situation, but it happens to anybody…” Theresa shared,

I feel like some people here, if they feel they aren’t safe, then they should work on that. If they feel like they can’t take care of themselves, they shouldn’t put themselves in situations where they can get taken advantage of.

Provide us with security

Students spoke of a range of existing and desired resources on campus they felt could help minimize occurrences of sexual violence or expedite response when an event happened. These included physical campus resources, such as safety lights and call boxes/buttons that could be used to solicit help, human campus resources such as security officer presence and availability of walking escort services, and transportation resources not necessarily operated by the campus but available on campus, including a safe bus or taxi and availability of rental bikes.

Call/security boxes and lights

Call boxes were identified as the primary mechanisms for seeking assistance from the security office on one campus; Leora commented, “I don’t know how you’d reach them unless you did [use] the call box.” At another campus, Hannes described an emergency station near a bus station as being in an ideal location from his perspective,

This is where people may feel threatened, and this is also where you push for help. What will happen is the lights will go off, and it will make a big sound, and help will rush here as fast as humanly possible. And again, it’s things like that that people feel a bit safer on campus, with things like these.

Although many students mentioned these security posts and call lights, it was not uncommon for them to have difficulty being able to locate one on campus during the interview. Eva referred to call boxes when she responded to a question about feeling sexually safe on campus and shared,

…if it happened to a friend I’d just say call 911 as soon as possible, or press the button and once in a while you’ll see those emergency, like, boxes around. Gosh, I can’t even remember if there’s any on campus, but I know I’ve seen them other places.

Andrea had a recommendation to improve this, “As far as I know, there are not very many [security posts]. Maybe that is one thing; they could have some more put in. I know this one. I don’t know where another one is.”

Security officers and escorts

Overwhelmingly, students had positive things to say regarding their knowledge of and interactions with security officers on campus. Edwin stated,

Security does a great job. The president of the university does a great job. She lets everyone know that it’s safe to be here…it’s safe to look over your shoulder, because we have these people looking out for you. If you ever feel scared and lonely, go to someone, here are the available resources. If you haven’t noticed, there are these blue poles on campus. If you press one of those…security will make sure you have an escort to where you need to go.

The expected speed at which security officers would arrive after the blue button was pushed ranged from “within 15 seconds” to “in whatever time they can get there.”

Some students were unsure of the services security officers provide, as demonstrated in Paulo’s response to a question about what the officers do, “Technically, I have no clue…they just drive around, give people parking tickets…I think that’s about it. I’ve got a couple myself.” On another campus Kim indicated she would go to security if there were a sexual violence incident but primarily associated security with citations, “They’re always walking around, or patrolling the parking lot. I got a warning citation for parking on the line, so I know they’re there.”

Other students were familiar with the role of some security officers as escorts. Hannes described his perspective of their activities, “they also have several people wearing the coats, having the walkie talkies, having tazers, walking around, just making sure nothing bad is happening around campus, maintaining order.” Leora shared,

They have a 24-hour escort service. You just call them…I’ve never used it. I’ve heard there’s good and bad reviews on it. I’ve heard some people say that they use it all the time. I’ve heard some people say that like, the people seem to be crabby when they came to pick them up, but I’m sure that varies, by like different nights, and what’s going on.

On some campuses, the security offices were located in places many students were unfamiliar with or unsure of how to find; on others, the offices were easily located by most students. For example, two students at the same college immediately pointed out where security could be found, “at the information desk” (Danson and Lukas). On one campus, the security office was in a female-only dorm building, limiting immediate access to only those students with keys to enter that specific dorm; Topher commented, “I’m a little bit stoked [agitated] about the fact that security is housed in a building that isn’t accessible to half of the student body.” For Eva, she viewed the physical police station on campus as a resource, “there’s also a police station really close by, so you know if I do have the opportunity, I will walk as close to that as possible…that makes me feel a little more secure.”

Transportation resources

Colin referred to safe bus transportation in his recommendation that during orientation week the campus should encourage students to be safe,

just say if you’re alone take the safe bus, and if you’re not, just always walk home with at least one person….I don’t know how many girls I see walking home alone [from the bars], and I just wish people would tell them not to do that.

On another campus, Theresa described the availability but inaccessibility of a campus-sponsored transportation service, “have you heard of the [bus service name]? The bus that drives around and picks people up. It’s like within a mile on campus. That line is always busy. Every time I’ve tried to call it, I’ve never gotten through.”

Educate us about sexual violence

Students readily provided recommendations for ways to be educated about sexual violence prevention and the available resources on campus. Existing educational programming and products were identified across all campuses with students’ opinions ranging from appreciating some of the events to preferring alternative resources. Commonly described events in which sexual violence was addressed included orientation and sponsored lectures or workshops. Available ongoing resources on campus included print materials located in a variety of places on campus, and some online tools. Campus staff members, including residence assistants and health service providers, were also identified as resources for education about sexual violence.

Events and services

Programs that are offered as part of orientation were described as ideal mechanisms for educating students about sexual violence and prevention. Trevor shared, “The most effective way is through the orientation program, and that’s actually where I’ve been. We did a class…about the legal aspects of sexual awareness and sexual assault.”

Another student, Tyler, shared about a unique event on his campus to raise awareness:

Tyler: The other day they rang bells on campus like every five minutes, for like raising sexual awareness about sexual abuse or something like that… Interviewer: Why did they ring bells every five minutes?

Tyler: I guess like a woman gets sexually abused every five minutes.

At one campus a student identified a crisis line service that is available to students twenty-four hours a day. Dao-Ming shared,

[That] is a center that has a crisis line if you have a rape, a relationship issue, any sexual issue…I personally have used the crisis line once…they were very helpful in getting back to me. It’s 24 hours and immediately when you call them, they will answer the phone right away and help you…it’s free.

Other students identified groups on campus or near campus that routinely offer sexual violence education and outreach to students, bringing in speakers, organizing awareness campaigns, and facilitating formation of active student groups to provide peer education. Students recommended campus-wide events to raise awareness, similar to other campaigns they have experienced to reduce waste, for example.

Print materials

Brochures were identified as sources of information regarding sexual assault, although most students admitted that while they have seen the brochures all around campus, they have not read one. Jacob read aloud the brochure topics, “Sexually transmitted infections, date rape equals not good, emergency contraceptive pills for females…sexual assault stuff, just a bunch of sexual offense services, that’s important.”

When asked if he had read a brochure, Jacob replied, “Um, no. I have not” but then indicated he felt others do read them,

Sometimes, I mean, if they have questions about it…I think some of them are like, you know, date rape, I don’t think many people just read that because I think people don’t think it’s going to happen. So they just kind of ignore it.

To address lack of use, some students suggested ways to make the information more appealing to students. Colin shared, “Honestly, I think making them funny not necessarily a joke because it’s not a joke, but maybe having some anecdotes in there.”

In contrast, students felt posters were readily accessible and students got very clear messages about sexual violence through them. Preferred locations for sexual violence-related posters include bathroom stalls, bulletin boards, and dormitories. For example, Joy shared,

But a lot of time when I’m on campus, you’ll see posters like this one that is just talking about it and how no means no…

Interviewer: Do you feel it’s a message that everybody gets?

Joy: I think it’s very, very clear! From the first moment when you first come on campus. It is very clear. It’s very, very clear. In every hall on every floor you see those posters about how everything in the situation may say ‘yes’, but if the person says ‘no’ that means no.

Online

Students used computers to access online resources during the go-along interviews. Specific to sexual violence prevention, the students most commonly located the safety and security links as well as the links identifying health services on campus. Forest shared what he would do in an urgent hypothetical situation following sexual violence toward himself or a friend, “I would probably find them [phone numbers] online and then pursue whatever option from there.”

Another student searched online through numerous links that took him to different branches of the campus before he eventually found the resources addressing sexual violence. Bill shared, “this process right here is a little more complicated than I expected it to be. It doesn’t seem to me like there is a direct link. That was extremely not quite as user friendly as I thought it would be.” On a different campus the process was relatively smooth; Charity said, “I’d go on-line. It’s right on the second page of the [campus name] website. Anybody outside the school could even find it. It’s really easy.” Some campus websites had specific sexual violence links, making the online search efficient; Leora shared,

yeah, sexual violence, is a specific link. Click on that and then you have ‘immediate assistance’ and ‘ongoing support’, different phone numbers and offices you might need. Most of them are not on campus.

Another student, Moriah, identified an online magazine put out by health services that occasionally includes content on sexual violence, “there’s different things…’New programs to prevent sexual assault’…you just scroll right over and this lady is talking.”

Staff

Residence assistants were identified as people students felt comfortable going to with questions related to sexual violence. Charity explained, “if you tell anything to an R.A. that you want to tell security, like if you’re too shy…they’ll go to them for you. They’re like your big sister or big brother and they’ll deal with it for you.” Another student, Colin, said, “I think if younger people taught us about this stuff, like maybe RA’s and hall directors instead of older doctors or therapists, I think it would get across more.”

Some, but not all, students described professors as resources; Trevor shared, “the biggest resource of how to know about these programs that are coming up is actual teachers telling you in class saying, ‘hey, here’s this speaker coming in’.” In one case, Peggy shared, “They went over sexual harassment; it was in the syllabus.”

Staff in wellness centers or health clinics on campus were also identified as sexual violence resources to access when students had questions or concerns. Charity said, “…just go to the Wellness Center and they can help you.” Georgina shared, “I think that you could probably talk to someone at Health Services or maybe one of the counselors on campus.”

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to describe male and female students’ perceptions of their college’s sexual violence prevention resources and efforts.

Students readily articulated concerns about sexual violence on campus, and perceptions about the relationship between sexual violence and substance use. This relationship, particularly for college students, has been substantiated in the literature (Palmer, McMahon, Rounsaville, & Ball, 2010; McCauley, Calhoun, & Gidycz, 2010), with some reporting that nearly three out of four victims were under the influence when they were assaulted (Mohler-Kuo, Dowdall, Koss, & Wechsler, 2004). Unintended drug use, including drug-facilitated sexual assault, was mentioned primarily by students on one campus where there has been increasing attention on use of ‘roofies.’ Lawyer, Resnick, Bakanic, Burkett, and Kilpatrick, (2010) have confirmed this relationship, stating, “drug-related sexual assaults on college campuses are more frequent than are forcible assaults and are most frequently preceded by voluntary alcohol consumption” (p. 453). Substance use, whether voluntary or forced, should be a primary target in any campus strategy to reduce sexual violence.

Although students perceived sexual violence as a problem on their campus, they also felt positive about the resources and services available to them. Students did not have difficulty identifying at least one available resource, although for those attending two-year schools in particular, there were generally fewer resources to describe. Indeed, a smaller proportion of students from the 2-year campuses mentioned sexual violence (53% compared with 92%); this could also be explained, however, by increased attention toward sexual violence on the 4- year campuses because of recent incidents that were reported in the media around the time interviews were conducted.

Males and females equally identified and criticized existing resources and programs, with females more likely to share personal experiences of sexual violence among their peers and males more often discussing male-focused educational events and some of their perceived myths surrounding sexual violence.

Students identified an array of campus-wide resources for sexual violence. Their appreciation of specific campus strategies such as using bathroom stalls to educate about sexual violence resources supported existing evidence; Konradi & DeBruin (2003) have shown that this strategy yields statistically significant increases in students’ understanding of sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) services specifically, and their inclination to encourage peers who have been assaulted to be seen by a SANE. Technologically innovative approaches to educating and reaching college students that were not mentioned widely but are worth considering in forensic nurse practice efforts include use of Facebook pages, text messaging, and Twitter or similar social media (California Family Health Council, 2011; Coker, 2011; RapedAtTufts, 2011; Sexual Violence Center, 2011).

Findings have implications for sexual violence prevention programs, reporting and medical/legal follow up. The students’ perceptions reinforce existing SANE protocols in many states that include the routine collection of blood and urine specimens so that testing for the presence of common facilitating drugs can be conducted (SAFEta, 2011). SANE programs might benefit from outreach to and collaboration with nearby college campuses, for example maintaining a website link about local SANE services on the college health services website. Certainly, SANEs should be resources to campus staff and students, and can be available to provide sexual violence prevention education during orientation or as a guest lecturer in a course. Local hospital-based SANE programs might explore the potential for offering SANE exams on campus, particularly in collaboration with college health services and advocacy programs.

This study provides insights that can contribute to the science and practice of forensic nursing yet should be considered within the context of some limitations. First, the study purpose was to examine sexual health resources on campuses, and sexual violence comments by participants were not necessarily in response to specific questions about sexual violence. A study primarily focused on sexual violence prevention, in contrast, would have allowed for more in-depth examination of some of the issues and resources, or lack of resources, that were raised. Second, the study did not include interviewing campus staff, or objectively conducting an environmental scan specific to sexual violence resources; future research might include these other sources of information.

Forensic nurses, and those with whom they collaborate, can use this study to inform educational and outreach strategies most likely to be well received and used by college students. A population at high risk for experiencing sexual violence, college students are also in “captive audience” situations during their campus life that should be capitalized upon to educate, intervene, and ensure that adequate sexual violence resources are available.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article:

This project is funded by grant R40MC17160 (M.E. Eisenberg, principal investigator) through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Research Program, and by Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Grant # K12HD055887 (N. Raymond, principal investigator) from the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development.

Thank you to participants for sharing their perspectives, and to participating institutions for facilitating the research. Thank you to Jennifer Neville for assistance with the literature review, and to Ellen Johnson, RN, SANE-A, CEN, CPEN, the SANE Program Supervisor at Regions Hospital, for providing feedback during manuscript development. This study was funded by grant R40 MC 17160, through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Research Program.

Biographies

Carolyn M. Garcia, PhD, MPH, RN, SANE is an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota School of Nursing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Kate E. Lechner is a graduate student at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Ellen A. Frerich, MSW, MPP is a graduate student at the University of Minnesota School of Nursing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Katherine A. Lust, PhD, MPH, RD is the Director of Research at Boynton Health Service, University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Marla E. Eisenberg, ScD, MPH is an assistant professor in the Division of Adolescent Health and Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Amar AF. African-American college women’s perceptions of resources and barriers when reporting forced sex. The Journal of the National Black Nurses Association. 2008;19(2):35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amar AF, Bess R, Stockbridge J. Lessons from families and communities about interpersonal violence, victimization, and seeking help. Journal of Forensic Nursing. 2010;6(3):110–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-3938.2010.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amar AF, Gennaro S. Dating violence in college women: Associated physical injury, healthcare usage, and mental health symptoms. Nursing Research. 2005;54(4):235–242. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association (ACHA) American College Health Association - National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Executive Summary, Spring 2010.Linthicum, MD: American College Health Association; 2010.Anderson, J. (2004). Talking whilst walking: A geographical archaeology of knowledge. Area. 2010;36(3):254. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley OS, Foshee VA. Adolescent help-seeking for dating violence: Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates, and sources of help. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2005;36(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Author, et al. Conducting go-along interviews to understand context and promote health. n.d.a doi: 10.1177/1049732312452936. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Author, et al. Through the eyes of the student: What college students look for, find, and think about sexual health resources on campus. n.d.b Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Avant EM, Swopes RM, Davis JL, Elhai JD. Psychological abuse and posttraumatic stress symptoms in college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0886260510390954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Ward S, Cohn ES, Plante EG, Moorhead C, Walsh W. Unwanted sexual contact on campus: A comparison of women’s and men’s experiences. Violence Vict. 2007;22(1):52–70. doi: 10.1891/vv-v22i1a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CM, Madsen SD, Nelson LJ, Carroll JS, Badger S. Friendship and romantic relationship qualities in emerging adulthood: Differential associations with identity development and achieved adulthood criteria. Journal of Adult Development. 2009;16:209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer HM, Rodriguez MA, Quiroga SS, Flores-Ortiz YG. Barriers to health care for abused Latina and Asian immigrant women. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2000;11(1):33–44. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton Health Service. College student health survey report, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- California Family Health Council. The Hookup. Teen Source. 2011 Retrieved August 15, 2011, from http://teensource.org/pages/hookup.

- Carpiano RM. Come take a walk with me: The “go-along” interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health Place. 2009;15(1):263. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements CM, Ogle RL. Does acknowledgment as an assault victim impact postassault psychological symptoms and coping? Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(10):1595–1614. doi: 10.1177/0886260509331486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Cook-Craig PG, Williams CM, Fisher BS, Clear ER, Garcia LS, Hegge LM. Evaluation of green dot: An active bystander intervention to reduce sexual violence on college campuses. Violence Against Women. 17(6):777–796. doi: 10.1177/1077801211410264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson CK, Macdonald A, Amstadter AB, Hanson R, de Arellano MA, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Risky behaviors and depression in conjunction with--or in the absence of--lifetime history of PTSD among sexually abused adolescents. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15(1):101–107. doi: 10.1177/1077559509350075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2020 - improving the health of Americans. 2010 http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx.

- Fisher BS, Daigle LE, Cullen FT, Turner MG. Reporting sexual victimization to the police and others; results form a national-level study of college women. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2003;30(1):6–38. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, Haney AP, Edwards P, Alessi EJ, Ardon M, Howell TJ. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth talk about experiencing and coping with school violence: A qualitative study. Journal of LGBT Youth. 2009;(6):24–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MJ. Health behavior in adolescent women reporting and not reporting intimate partner violence. Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010;39(3):263–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PI. Exploring space and place with walking interviews. Journal of Research Practice. 2008;4(2) [Google Scholar]

- Kaltman S, Krupnick J, Stockton P, Hooper L, Green BL. Psychological impact of types of sexual trauma among college women. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(5):547–555. doi: 10.1002/jts.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konradi A, DeBruin PL. Using a social marketing approach to advertise sexual assault nurse examination (SANE) service to college students. J Am Coll Health. 2003;52(1):33–39. doi: 10.1080/07448480309595721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Warner TD, Fisher BS, Martin SL. College women’s experiences with physically forced, alcohol- or other drug-enabled, and drug-facilitated sexual assault before and since entering college. Journal of American College Health. 2009;57(6):639–647. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.6.639-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusenbach M. Street phenomenology: The go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography. 2003;4(3):455. [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer S, Resnick H, Bakanic V, Burkett T, Kilpatrick D. Forcible, drug-facilitated, and incapacitated rape and sexual assault among undergraduate women. Journal of American College Health. 2010;58(5):453–460. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley JL, Calhoun KS, Gidycz CA. Binge drinking and rape: A prospective examination of college women with a history of previous sexual victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25(9):1655–1658. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Coates AA, Gaffey KJ, Johnson CF. Sexuality, substance use, and susceptibility to victimization: Risk for rape and sexual coercion in a prospective study of college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(12):1730–1746. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler-Kuo M, Dowdall GW, Koss MP, Wechsler H. Correlates of rape while intoxicated in a national sample of college women. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(1):37–45. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhr T. ATLAS.ti GmbH v. 6.2 [computer software] Berlin: ATLAS.ti; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nasta A, Shah B, Brahmanandam S, Richman K, Wittels K, Allsworth J, Boardman L. Sexual victimization: Incidence, knowledge and resource use among a population of college women. Journal of Pediatric Adolescent Gynecology. 2005;18(2):91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RS, McMahon TJ, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA. Coercive sexual experiences, protective behavioral strategies, alcohol expectancies and consumption among male and female college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25(9):1563–1578. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JL, McQuiller-Williams L. Intimate violence among underrepresented groups on a college campus. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0886260510393011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RapedAtTufts. Raped At Tufts.Info. Tufts University Survivors of Sexual Violence. 2011 Retrieved August 15, 2011, from http://rapedattufts.info/

- Rennison CM. Rape and sexual assault: Reporting to police and seeking medical attention. 1992–2000. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2002. Report NCJ 194530. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London: SAGE Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Rigor or rigor mortis: The problem of rigor in qualitative research revisited. Advances in Nursing Science. 1993;16(2):1–8. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner Technical Assistance (SAFEta) The examination process. SAFEta source. 2011 Retrieved September 1, 2011, from http://www.safeta.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=142.

- Sexual Violence Center. Active Bystander Training “Green Dot”. Sexual Violence Center. 2011 Retrieved August 15, 2011, from http://www.sexualviolencecenter.org/activeBy.html.

- Stepakoff S. Effects of sexual victimization on suicidal ideation and behavior in U.S. college women. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 1998;28(1):107–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschumper A, Narring F, Meier C, Michaud PA. Sexual victimization in adolescent girls (age 15–20 years) enrolled in post-mandatory schools or professional training programmes in Switzerland. Acta Paediatr. 1998;(87):212–217. doi: 10.1080/08035259850157697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh WA, Banyard VL, Moynihan MM, Ward S, Cohn ES. Disclosure and service use on a college campus after an unwanted sexual experience. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2010;11(2):134–151. doi: 10.1080/15299730903502912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]