Abstract

Sarcopenia, the age-related loss of skeletal muscle, is characterized by a deterioration of muscle quantity and quality leading to a gradual slowing of movement, a decline in strength and power, and an increased risk of fall-related injuries. Since sarcopenia is largely attributed to various molecular mediators affecting fiber size, mitochondrial homeostasis, and apoptosis, numerous targets exist for drug discovery. In this paper, we summarize the current understanding of the endocrine contribution to sarcopenia and provide an update on hormonal intervention to try to improve endocrine defects. Myostatin inhibition seems to be the most interesting strategy for attenuating sarcopenia other than resistance training with amino acid supplementation. Testosterone supplementation in large amounts and at low frequency improves muscle defects with aging but has several side effects. Although IGF-I is a potent regulator of muscle mass, its therapeutic use has not had a positive effect probably due to local IGF-I resistance. Treatment with ghrelin may ameliorate the muscle atrophy elicited by age-dependent decreases in growth hormone. Ghrelin is an interesting candidate because it is orally active, avoiding the need for injections. A more comprehensive knowledge of vitamin-D-related mechanisms is needed to utilize this nutrient to prevent sarcopenia.

1. Introduction

Age-related declines in muscle mass and strength, known as sarcopenia, are often an important antecedent of the onset of disability in older adulthood. Although the term is applied clinically to denote loss of muscle mass, sarcopenia is often used to describe both a set of cellular processes (denervation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammatory and hormonal changes) and a set of outcomes such as decreased muscle strength, decreased mobility and function [1], increased fatigue, a greater risk of falls [2], and reduced energy needs. Lean muscle mass generally contributes up to ~50% of total body weight in young adults but declines with aging to be 25% at 75–80 years old [3, 4]. The loss of muscle mass is typically offset by gains in fat mass. The loss is most notable in the lower limb muscle groups, with the cross-sectional area of the vastus lateralis being reduced by as much as 40% between the ages of 20 and 80 yr [5].

Several possible mechanisms for age-related muscle atrophy have been described; however, the precise contribution of each is unknown. Age-related muscle loss is a result of reductions in the size and number of muscle fibers [6] possibly due to a multifactorial process that involves physical activity, nutritional intake, oxidative stress, and hormonal changes [2, 7]. The specific contribution of each of these factors is unknown, but there is emerging evidence that the disruption of several positive regulators (Akt and serum response factor) of muscle hypertrophy with age is an important feature in the progression of sarcopenia [8–10]. In contrast, many investigators have failed to demonstrate an age-related enhancement in levels of common negative regulators (Atrogin-1, myostatin, and calpain) in senescent mammalian muscles.

Several lines of evidence point to inflammation being associated with loss of muscle strength and mass with aging [11]. Animal studies have shown that the administration of interleukin (IL)-6 or tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α increases skeletal muscle breakdown, decreases the rate of protein synthesis, and reduces plasma concentrations of insulin-like growth factor [12, 13]. In older men and women, higher levels of IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) were associated with a two- to threefold greater risk of losing more than 40% of grip strength over 3 years [14]. On the other hand, several studies have indicated age-related endocrine defects such as decreases in anabolic hormones (testosterone, estrogen, growth hormone (GH), and insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I)) [15–18]. Although hormonal supplementation for the elderly has been conducted on a large scale, it was found not to be effective against sarcopenia and to have minor side effects [9, 10, 15, 16, 19, 20]. In this paper, we summarize the current understanding of the endocrine contribution to sarcopenia and provide an update on practical hormonal intervention for the elderly.

2. The Adaptative Changes in Catabolic Mediators

2.1. TNF-α

Inflammation may negatively influence skeletal muscle through direct catabolic effects or through indirect mechanisms (i.e., decreases in GH and IGF-I concentrations, induction of anorexia, etc.) [21]. There is growing evidence that higher levels of inflammatory markers are associated with physical decline in older individuals, possibly through the catabolic effects of these markers on muscle. In an observational study of more than 2000 men and women, TNF-α showed a consistent association with declines in muscle mass and strength [22]. The impact of inflammation on the development of sarcopenia is further supported by a recently published animal study showing that a reduction in low-grade inflammation by ibuprofen in old (20 months) rats resulted in a significant decrease in muscle mass loss [23]. An age-related disruption of the intracellular redox balance appears to be a primary causal factor for a chronic state of low-grade inflammation. More recently, Chung et al. [24] hypothesized that abundant nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) protein induced age-related increases in IL-6 and TNF-α. Moreover, reactive oxygen species (ROS) also appear to function as second messengers for TNF-α in skeletal muscle, activating NF-κB either directly or indirectly [25]. Indeed, marked production of ROS has been documented in muscle of the elderly [26, 27]. However, it is not clear whether NF-κB signaling is enhanced with age. Despite some evidence supporting enhanced NF-κB signaling in type I fibers of aged skeletal muscle, direct evidence for increased activation and DNA binding of NF-κB is lacking [28, 29]. For example, Phillips and Leeuwenburgh [29] found that neither p65 protein expression nor the binding activity of NF-κB was significantly altered in the vastus lateralis muscles of 26-month-old rats despite the marked upregulation of TNF-α expression in both blood and muscle. Upregulated TNF-α expression in serum and muscle seems to enhance apoptosis through increased mitochondrial defects resulting in a loss of muscle fibers [29–31]. It has been shown that TNF-α is one of the primary signals inducing apoptosis in muscle.

2.2. Myostatin

Myostatin was first discovered during screening for new members of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily and shown to be a potent negative regulator of muscle growth [32]. Like other family members, myostatin is synthesized as a precursor protein that is cleaved by furin proteases to generate the active C-terminal dimer. Most, if not all, of the myostatin protein that circulates in blood also appears to exist in an inactive complex with a variety of proteins, including the propeptide [33]. The latent form of myostatin seems to be activated in vitro by dissociation from the complex with either acid or heat treatment [33, 34] or by proteolytic cleavage of the propeptide with members of the bone morphogenetic protein-1/tolloid family of metalloproteases [34].

Studies indicate that myostatin inhibits cell cycle progression and reduces levels of myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), thereby controlling myoblastic proliferation and differentiation during developmental myogenesis [35–37]. Myostatin binds to and signals through a combination of ActRIIA/B receptors on the cell membrane but has higher affinity for ActRIIB. On binding to ActRIIB, myostatin forms a complex with either activin receptor-like kinase (ALK) 4 or ALK5 to activate (phosphorylate) the Smad2/3 transcription factors. Then Smad2/3 are translocated and modulate the nuclear transcription of genes such as MyoD [38] via a TGF-β-like mechanism. More recently, the IGF-I-Akt-mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, which mediates both differentiation in myoblasts and hypertrophy in myotubes, has been shown to inhibit myostatin-dependent signaling. Blockade of the Akt-mTOR pathway, using siRNA to RAPTOR, a component of TORC1 (TOR signaling complex 1), facilitates myostatin's inhibition of muscle differentiation because of an increase in Smad2 phosphorylation [39]. In contrast, Smad2/3 inhibition promotes muscle hypertrophy partially dependent on mTOR signaling [40].

Several researchers have investigated the effect of inhibiting myostatin to counteract sarcopenia using animals [41, 42]. Lebrasseur et al. [41] found that treatment with a mouse chimera of antihuman myostatin antibody (24 mg/Kg, 4 weeks), a drug for inhibiting myostatin, elicited a significant increase in muscle mass and in running performance probably due to decreased levels of phosphorylated Smad3 and Muscle ring finger-1 (MuRF-1). More recently, Murphy et al. [42] showed, by way of once weekly injections, that a lower dose of this anti-human myostatin antibody (10 mg/Kg) significantly increased the fiber cross-sectional area (by 12%) and in situ muscle force (by 35%) of aged mice (21 mo old). These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of antibody-directed myostatin inhibition for sarcopenia by inhibiting protein degradation. Although many researchers expect myostatin levels to be increased not only in muscle but also in serum, blood myostatin levels have not been shown to increase with age [43].

2.3. Glucocorticoid

Glucocorticoid-associated atrophy appears to be specific to type II or phasic muscle fibers. In a study of controlled hypercortisolaemia in healthy men [44], experimental inactivity increased the catabolic effect of glucocorticoids, suggesting that an absence of mechanical signals potentiates the effect. The mechanism of glucocorticoid-induced atrophy may involve upregulated expression of myostatin and glutamine synthetase, the latter via the glucocorticoid receptor's interaction with the glutamine synthetase promoter [45]. Glucocorticoids inhibit the physiological secretion of GH and appear to induce IGF-I activity in target organs. Changes in steroid-induced glutamine synthetase represent a potential mechanism of action, and dose-dependent inhibition of glutamine synthetase by IGF-I was observed in rat L6 cells [46].

The increased incidence of various diseased states during aging is associated with the hypersecretion of glucocorticoids [47, 48]. In addition, when adult (7-month-old) and aged (22-month-old) rats received dexamethasone (approximately 500 μg/Kg body weight/day) in their drinking water for 5-6 days, muscle wasting was much more rapid in aged animals [47]. Furthermore, glucocorticoids induced prolonged leucine resistance to muscle protein synthesis in old rats [49]. Still, it remains to be directly elucidated, using pharmacological inhibitors for glucocorticoids, whether age-related increases in serum glucocorticoid levels actually inhibit protein synthesis and/or enhance protein degradation.

2.4. Interleukin-6 and CRP

IL-6 and CRP, known as “geriatric cytokines,” are multifunctional cytokine produced in situations of trauma, stress, and infection. During the aging process, levels of both IL-6 and CRP in plasma become elevated. The natural production of cytokines is likely beneficial during inflammation, but overproduction and the maintaining of an inflammatory state for long periods of time, as seen in elderly individuals, are detrimental [50, 51]. A number of authors have demonstrated that a rise in plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines, especially IL-6, and proteins under acute conditions is associated with a reduction in mobility as well as a reduced capacity to perform daily activities, the development of fragility syndrome, and increased mortality rates [50–52]. In older men and women, higher levels of IL-6 and CRP were associated with a two- to threefold greater risk of losing more than 40% of grip strength over 3 years [14]. In contrast, there were no longitudinal associations between inflammatory markers and changes in grip strength among high functioning elderly participants from the MacArthur Study of Successful Ageing [53]. More recently, Hamer and Molloy [54] demonstrated, in a large representative community-based cohort of older adults (1,926 men and 2,260 women (aged 65.3 ± 9.0 years)), that CRP was associated with poorer hand grip strength and chair stand performance in women but only chair stand performance in men. In addition, Haddad et al. [55] demonstrated atrophy in the tibialis anterior muscle of mice following the injection of relatively low doses of IL-6.

In a recent randomized trial that employed aerobic and strength training in a group of elderly participants, significant reductions in various inflammatory markers (IL-6, CRP, and IL-18) were observed for aerobic but not strength training [56]. In contrast, combined resistance and aerobic training that increased strength by 38% resulted in significant reductions in CRP [57]. More descriptive data appears to be needed whether IL-6 and CRP have an actual catabolic effect in sarcopenic muscle.

3. Anabolic Hormones in Sarcopenic Muscle

3.1. Testosterone

In males, levels of testosterone decrease by 1% per year, and those of bioavailable testosterone by 2% per year from age 30 [16, 58, 59]. In women, testosterone levels drop rapidly from 20 to 45 years of age [60]. Testosterone increases muscle protein synthesis [61], and its effects on muscle are modulated by several factors including genetic background, nutrition, and exercise [62].

Numerous studies of treatment with testosterone in the elderly have been performed over the past few years [63–66]. In 1999, Snyder et al. [66] suggested that increasing the level of testosterone in old men to that seen in young men increased muscle mass but did not result in functional gains in strength. Systemic reviews of the literature [67] have concluded that testosterone supplementation attenuates several sarcopenic symptoms including decreases in muscle mass [64–66] and grip strength [63]. For instance, a recent study of 6 months of supraphysiological dosage of testosterone in a randomized placebo-controlled trial reported increased leg lean body mass and leg and arm strength [68]. Although there are significant increases in strength among elderly males given high doses of testosterone, the potential risks may outweigh the benefits. Risks associated with testosterone therapy in older men include sleep apnea, thrombotic complications, and the increased risk of prostate cancer [69].

These side effects have driven the necessity for drugs that demonstrate improved therapeutic profiles. Novel, nonsteroidal compounds, called selective androgen receptor modulators, have shown tissue-selective activity and improved pharmacokinetic properties. Whether these drugs are effective in treating sarcopenia has yet to be shown [70]. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is marketed as a nutritional supplement in the USA and is available over the counter. Unlike testosterone and estrogen, DHEA is a hormone precursor which is converted into sex hormones in specific target tissues [71]. However, supplementation of DHEA in aged men and women resulted in an increase in bone density and testosterone and estradiol levels, but no changes in muscle size, strength, or function [72, 73].

3.2. Estrogen

It has been hypothesized that menopause transition and the subsequent decline in estrogen may play a role in muscle mass loss [7, 18]. Van Geel et al. [74] reported a positive relationship between lean body mass and estrogen levels. Similarly, Iannuzzi-Sucich et al. [75] observed that muscle mass is correlated significantly with plasma estrone and estradiol levels in women. However, Baumgartner et al. [76] reported that estrogen levels were not associated with muscle mass in women aged 65 years and older. The mechanisms by which decrease in estrogen levels may have a negative effect on muscle mass are not well understood but may be associated with an increase in proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, which might be implicated in the apparition of sarcopenia [77]. Furthermore, estrogen could have a direct effect on muscle mass since it has been shown that skeletal muscle has estrogen beta-receptors on the cell membrane [78]. Therefore, a direct potential mechanistic link could exist between low estrogen levels and a decrease in protein synthesis. Further studies are needed to investigate this hypothesis. Nevertheless, before reaching a conclusion on the contribution of estrogens to the onset of sarcopenia, it would be important to measure urinary estrogen metabolites since a relationship between breast cancer and urinary estrogen metabolites has been shown [79].

3.3. GH

Growth hormone (GH) is a single-chain peptide of 191 amino acids produced and secreted mainly by the somatotrophs of the anterior pituitary gland. GH coordinates the postnatal growth of multiple target tissues, including skeletal muscle [80]. GH secretion occurs in a pulsatile manner with a major surge at the onset of slow-wave sleep and less conspicuous secretory episodes a few hours after meals [81] and is controlled by the actions of two hypothalamic factors, GH-releasing hormone (GHRH), which stimulates GH secretion, and somatostatin, which inhibits GH secretion [82]. The secretion of GH is maximal at puberty accompanied by very high circulating IGF-I levels [83], with a gradual decline during adulthood. Indeed, circulating GH levels decline progressively after 30 years of age at a rate of ~1% per year [84]. In aged men, daily GH secretion is 5- to 20-fold lower than that in young adults [85]. The age-dependent decline in GH secretion is secondary to a decrease in GHRH and to an increase in somatostatin secretion [86].

With respect to the somatomedin hypothesis, the growth-promoting actions of GH are mediated by circulating or locally produced IGF-I [87]. GH-induced muscle growth may be mediated in an endocrine manner by circulating IGF-I derived from liver and/or in an autocrine/paracrine manner by direct expression of IGF-I from target muscle via GH receptors on muscle membranes. The effects of GH administration on muscle mass, strength and physical performance are still under debate [19]. In animal models, GH treatment is very effective at inhibiting sarcopenic symptoms such as muscle atrophy and decreases in protein synthesis particularly in combination with exercise training [88]. The effect of GH treatment for elderly subjects is controversial. Some groups demonstrated an improvement in strength after long-term administration (3–11 months) of GH [89]. In contrast, many researchers have found that muscle strength or muscle mass did not improve on supplementation with GH [19, 89]. One recent study reported a positive effect for counteracting sarcopenia after the administration of both GH and testosterone [90]. Several reasons may underlie the ineffectiveness of GH treatment in improving muscle mass and strength in the elderly, such as a failure of exogeneous GH to mimic the pulsatile pattern of natural GH secretion or the induction of GH-related insulin resistance. In addition, reduced mRNA levels of the GH receptor in skeletal muscle have been observed in older versus younger healthy men, exhibiting a significant negative relationship with myostatin levels [91]. It should also be considered that the majority of the trials conducted on GH supplementation have reported a high incidence of side effects, including soft tissue edema, carpal tunnel syndrome, arthralgias, and gynecomastica, which pose serious concerns especially in older adults. Therefore, one should pay very careful attention when administering GH to the elderly.

There is evidence that the age-associated decline in GH levels in combination with lower IGF-I levels contributes to the development of sarcopenia [92]. IGF-I is perhaps the most important mediator of muscle growth and repair [93] possibly by utilizing Akt-mTOR-p70S6K (p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase) signaling. Although the transgenic approach of upregulating IGF-I expression in skeletal muscle would be appropriate for inhibiting sarcopenia, the administration of IGF-I to the elderly has resulted in controversial findings on muscle strength and function [94]. The ineffectiveness may be attributable to age-related insulin resistance to amino acid transport and protein synthesis [95] or a marked decrease in IGF-I receptors [96, 97] and receptor affinity for IGF-I [98] in muscle with age. Wilkes et al. [99] demonstrated a reduced effect of insulin on protein breakdown in the legs in older versus younger subjects probably due to the blunted activation of Akt by insulin. More comprehensive reviews on insulin resistance in sarcopenia can be found elsewhere [95].

3.4. Ghrelin

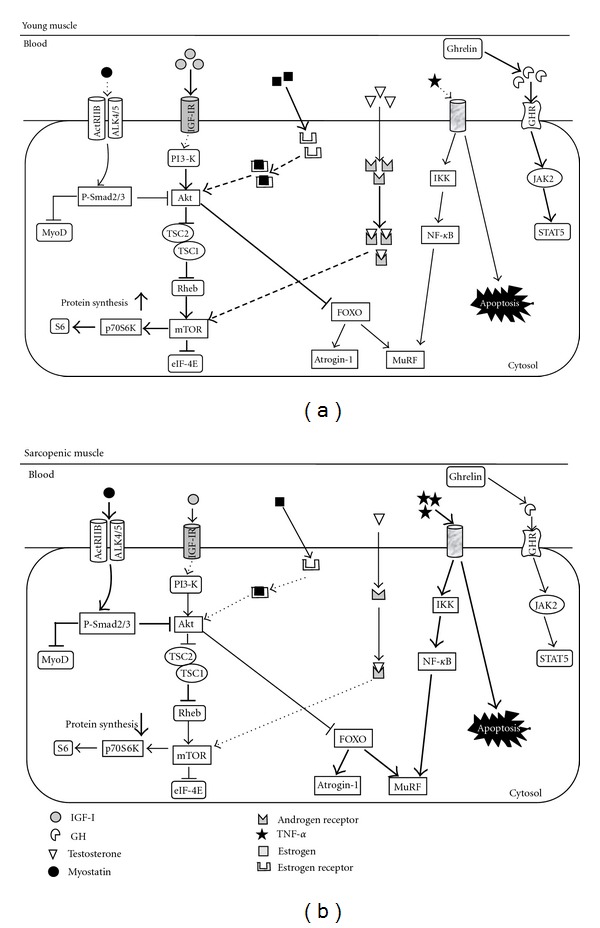

Ghrelin is a 28-amino-acid peptide mainly produced by cells in the stomach, intestines, and hypothalamus [100]. Ghrelin is a natural ligand for the GH-secretagogue receptor (GHS-R), which possesses a unique fatty acid modification, an n-octanoylation, at Ser 3 [101]. Ghrelin plays a critical role in a variety of physiological processes, including the stimulation of GH secretion and regulation of energy homeostasis by stimulating food intake and promoting adiposity via a GH-independent mechanism [100]. In contrast, ghrelin inhibits the production of anorectic proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α [102]. Because of their combined anabolic effects on skeletal muscle and appetite, ghrelin and low-molecular-weight agonists of the ghrelin receptor are considered attractive candidates for the treatment of cachexia [103]. For example, Nagaya et al. [104] gave human ghrelin (2 μg/Kg twice daily intravenously) for 3 weeks to cachexic patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in an open-label study. After ghrelin therapy, significant increases from baseline measurements were observed for body weight, lean body mass, food intake, hand grip strength, maximal inspiratory pressure, and Karnofsky performance score [104]. In another unblinded study, the same group demonstrated that treatment with human ghrelin (2 μg/Kg twice daily intravenously, 3 weeks) significantly improved several parameters (eg., lean body mass measured by dual-energy X-ray absorption and left ventricular ejection fraction) in 10 patients with chronic heart failure [105]. In a 1-year placebo-controlled study in healthy older adults over the age of 60 years given an oral ghrelin-mimetic (MK-677), an increase in appetite was observed [106]. The study did not show a significant increase in strength or function in the ghrelin-mimetic treatment group, when compared to the placebo group; however, a tendency was observed [106]. As pointed out in a recent review by Nass et al. [20], the use of this compound induces the potential deterioration of insulin sensitivity and development of diabetes mellitus in older adults with impaired glucose tolerance. Figure 1 provides an overview of several regulators for muscle mass in both young and sarcopenic mammalian muscles.

Figure 1.

(a) In young muscle, abundant serum IGF-I can stimulate protein synthesis by activating Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway. Akt blocks the nuclear translocation of FOXO to inhibit the expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF and the consequent protein degradation. Abundant serum GH, which is induced by ghrelin, activates JAK2-STAT5 signaling to promote muscle-specific gene transcription necessary to hypertrophy. In young muscle, testosterone and estrogen bind these intramuscular receptors (androgen receptor and estrogen receptor (α and β)), and activate mTOR and Akt, respectively. Lower serum amount of myostatin and TNF-α failed to activate signaling candidates (Smad 2/3, NF-κB, etc.) enhancing protein degradation. (b) In sarcopenic muscle, myostatin signals through the activin receptor IIB (ActRIIB), ALK4/5 heterodimer seems to activate Smad2/3 and blocking of MyoD transactivation in an autoregulatory feedback loop. Abundant activated Smad2/3 inhibit protein synthesis probably due to blocking the functional role of Akt. The increased blood TNF-α elevates the protein degradation through IKK/NF-κB signaling and enhance an apoptosis. Lower serum amount of IGF-I, GH, and anabolic hormones (testosterone and estrogen) failed to activate signaling candidates (Akt, mTOR, STAT5, etc.) enhancing protein synthesis. The impaired regulation of FOXO by Akt results in abundant expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF and the consequent protein degradation in sarcopenic muscle.

3.5. Vitamin D

Vitamin D has been traditionally considered a key regulator of bone metabolism and calcium and phosphorus homeostasis through negative feedback with the parathyroid hormone [107, 108]. It is also well established that vitamin D deficiency causes rickets in children and osteomalacia and osteoporosis in adults. A large and growing body of evidence suggests that vitamin D is not only necessary for bone tissue and calcium metabolism but may also represent a crucial determinant for the development of major (sub)clinical conditions and health-related events [107, 109].

Today, approximately 1 billion, mostly elderly people, worldwide have vitamin D deficiency. The prevalence of low vitamin D concentrations in subjects older than 65 years of age has been estimated at approximately 50% [110–112], but this figure is highly variable because it is influenced by sociodemographic, clinical, therapeutic, and environmental factors. Similarly there is an age-dependent reduction in vitamin D receptor expression in skeletal muscle [113]. Prolonged vitamin D deficiency has been associated with severe muscle weakness, which improves with vitamin D supplementation [114]. The histological examination of muscle tissue from subjects with osteomalacia is characterized by increased interfibrillar space, intramuscular adipose tissue infiltrates, and fibrosis [115]. Interestingly, muscle biopsies performed before and after vitamin D supplementation have documented an increased number and sectional area of type II (or fast) muscle fibers [113, 116].

A large body of evidence currently demonstrates that low vitamin D concentrations represent an independent risk factor for falls in the elderly [117–119]. Supplementation with vitamin D in double-blind randomized-controlled trials has been shown to increase muscle strength and performance and reduce the risk of falling in community-living elderly and nursing home residents with low vitamin D levels [120–124]. In contrast, several groups found no positive effect of vitamin D supplementation on fall event outcomes [125–127]. Cesari et al. [128] attributed these contradictory findings to the selection criteria adopted to recruit study populations, adherence to the intervention, or the extreme heterogeneity of cut-points defining the status of deficiency. A more comprehensive knowledge on vitamin-D-related mechanisms may provide a very useful tool preventing muscle atrophy for older persons (sarcopenia).

4. Conclusion

Given the current and future demographic age shift in the world's population, intense research in this area is imperative. Decreases in muscle mass have been shown to be a key element in the development of frailty. Currently, resistance training combined with amino-acid-containing supplements would be the best way to prevent age-related muscle wasting and weakness. Comprehensive trials have demonstrated that supplementation with GH, IGF-I, or estrogen has a minor sarcopenia-inhibiting effect. Testosterone supplementation in large amounts improves muscle defects with aging but has several side effects. Ghrelin-mimetics which have the ability to increase caloric intake as well as to increase lean body mass in the older population could be potentially beneficial and reverse the catabolic state associated with sarcopenia. Myostatin inhibition seems to be an intriguing strategy for attenuating sarcopenia as well as muscular dystrophy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research C (no. 23500778) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Abbreviations

- ActRIIB:

Activin type IIB receptor

- ALK:

Activin receptor-like kinase

- CRP:

C-reactive protein

- DHEA:

Dehydroepiandrosterone

- GH:

Growth hormone

- GHRH:

Growth hormone releasing hormone

- IGF-I:

Insulin-like growth factor-I

- IL:

Interleukin

- mTOR:

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- MuRF-1:

Muscle ring finger-1

- NF-κB:

Nuclear factor-kappaB

- p70S6K:

p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- TNF-α:

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- TORC1:

TOR signaling complex 1.

References

- 1.Melton LJ, III, Khosla S, Crowson CS, O’Connor MK, O’Fallon WM, Riggs BL. Epidemiology of sarcopenia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(6):625–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgartner RN, Waters DL, Gallagher D, Morley JE, Garry PJ. Predictors of skeletal muscle mass in elderly men and women. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 1999;107(2):123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Short KR, Nair KS. The effect of age on protein metabolism. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2000;3(1):39–44. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Short KR, Vittone JL, Bigelow ML, Proctor DN, Nair KS. Age and aerobic exercise training effects on whole body and muscle protein metabolism. American Journal of Physiology. 2004;286(1):E92–E101. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00366.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lexell J. Human aging, muscle mass, and fiber type composition. Journals of Gerontology. 1995;50:11–16. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.special_issue.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lexell J. Ageing and human muscle: observations from Sweden. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology. 1993;18(1):2–18. doi: 10.1139/h93-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roubenoff R, Hughes VA. Sarcopenia: current concepts. Journals of Gerontology. 2000;55(12):M716–M724. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.12.m716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakuma K, Akiho M, Nakashima H, Akima H, Yasuhara M. Age-related reductions in expression of serum response factor and myocardin-related transcription factor A in mouse skeletal muscles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2008;1782(7–8):453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakuma K, Yamaguchi A. Molecular mechanisms in aging and current strategies to counteract sarcopenia. Current Aging Science. 2010;3(2):90–101. doi: 10.2174/1874609811003020090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakuma K, Yamaguchi A. Cell Aging. New York, NY, USA: Nova Science; 2011. Sarcopenia: molecular mechanisms and current therapeutic strategy ; pp. 93–152. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomson DM, Gordon SE. Impaired overload-induced muscle growth is associated with diminished translational signalling in aged rat fast-twitch skeletal muscle. Journal of Physiology. 2006;574(1):291–305. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.107490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Degens H. The role of systemic inflammation in age-related muscle weakness and wasting. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2010;20(1):28–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grounds MD. Reasons for the degeneration of ageing skeletal muscle: a central role for IGF-1 signalling. Biogerontology. 2002;3(1–2):19–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1015234709314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaap LA, Pluijm SMF, Deeg DJH, Visser M. Inflammatory markers and loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia) and strength. American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119(6):526.e9–526.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drey M. Sarcopenia-pathophysiology and clinical relevance. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 2011;161(17–18):402–408. doi: 10.1007/s10354-011-0002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakuma K, Yamaguchi A. Sarcopenia and cachexia: the adaptations of negative regulators of skeletal muscle mass. doi: 10.1007/s13539-011-0052-4. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sattler FR, Castaneda-Sceppa C, Binder EF, et al. Testosterone and growth hormone improve body composition and muscle performance in older men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;94(6):1991–2001. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas DR. Loss of skeletal muscle mass in aging: examining the relationship of starvation, sarcopenia and cachexia. Clinical Nutrition. 2007;26(4):389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giovannini S, Marzetti E, Borst SE, Leeuwenburgh C. Modulation of GH/IGF-1 axis: potential strategies to counteract sarcopenia in older adults. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2008;129(10):593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nass R, Johannsson G, Christiansen JS, Kopchick JJ, Thorner MO. The aging population—is there a role for endocrine interventions? Growth Hormone and IGF Research. 2009;19(2):89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roubenoff R. Catabolism of aging: is it an inflammatory process? Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2003;6(3):295–299. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000068965.34812.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaap LA, Pluijm SMF, Deeg DJH, et al. Higher inflammatory marker levels in older persons: associations with 5-year change in muscle mass and muscle strength. Journals of Gerontology. 2009;64(11):1183–1189. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rieu I, Magne H, Savary-Auzeloux I, et al. Reduction of low grade inflammation restores blunting of postprandial muscle anabolism and limits sarcopenia in old rats. Journal of Physiology. 2009;587(22):5483–5492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.178319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung HY, Cesari M, Anton S, et al. Molecular inflammation: underpinnings of aging and age-related diseases. Ageing Research Reviews. 2009;8(1):18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reid MB, Li YP. Tumor necrosis factor-α and muscle wasting: a cellular perspective. Respiratory Research. 2001;2(5):269–272. doi: 10.1186/rr67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aoi W, Sakuma K. Oxidative stress and skeletal muscle dysfunction with aging . Current Aging Science. 2011;4(2):101–109. doi: 10.2174/1874609811104020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meng SJ, Yu LJ. Oxidative stress, molecular inflammation and sarcopenia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2010;11(4):1509–1526. doi: 10.3390/ijms11041509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bar-Shai M, Carmeli E, Coleman R, et al. The effect of hindlimb immobilization on acid phosphatase, metalloproteinases and nuclear factor-κB in muscles of young and old rats. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2005;126(2):289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philips T, Leeuwenburgh C. Muscle fiber specific apoptosis and TNF-α signaling in sarcopenia are attenuated by life-long calorie restriction. The FASEB Journal. 2005;19(6):668–670. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2870fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marzetti E, Carter CS, Wohlgemuth SE, et al. Changes in IL-15 expression and death-receptor apoptotic signaling in rat gastrocnemius muscle with aging and life-long calorie restriction. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2009;130(4):272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pistilli EE, Jackson JR, Alway SE. Death receptor-associated pro-apoptotic signaling in aged skeletal muscle. Apoptosis. 2006;11(12):2115–2126. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0194-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SJ. Regulation of muscle mass by myostatin. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2004;20:61–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.012103.135836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimmers TA, Davies MV, Koniaris LG, et al. Induction of cachexia in mice by systemically administered myostatin. Science. 2002;296(5572):1486–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1069525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolfman NM, McPherron AC, Pappano WN, et al. Activation of latent myostatin by the BMP-1/tolloid family of metalloproteinases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(26):15842–15846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2534946100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langley B, Thomas M, Bishop A, Sharma M, Gilmour S, Kambadur R. Myostatin inhibits myoblast differentiation by down-regulating MyoD expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(51):49831–49840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas M, Langley B, Berry C, et al. Myostatin, a negative regulator of muscle growth, functions by inhibiting myoblast proliferation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(51):40235–40243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004356200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang W, Zhang Y, Li Y, Wu Z, Zhu D. Myostatin induces cyclin D1 degradation to cause cell cycle arrest through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/GSK-3β pathway and is antagonized by insulin-like growth factor 1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(6):3799–3808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen DL, Unterman TG. Regulation of myostatin expression and myoblast differentiation by FoxO and SMAD transcription factors. American Journal of Physiology. 2007;292(1):C188–C199. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00542.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trendelenburg AU, Meyer A, Rohner D, Boyle J, Hatakeyama S, Glass DJ. Myostatin reduces Akt/TORC1/p70S6K signaling, inhibiting myoblast differentiation and myotube size. American Journal of Physiology. 2009;296(6):C1258–C1270. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00105.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sartori R, Milan G, Patron M, et al. Smad2 and 3 transcription factors control muscle mass in adulthood. American Journal of Physiology. 2009;296(6):C1248–C1257. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00104.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LeBrasseur NK, Schelhorn TM, Bernardo BL, Cosgrove PG, Loria PM, Brown TA. Myostatin inhibition enhances the effects of exercise on performance and metabolic outcomes in aged mice. Journals of Gerontology. 2009;64(9):940–948. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy KT, Koopman R, Naim T, et al. Antibody-directed myostatin inhibition in 21-mo-old mice reveals novel roles for myostatin signaling in skeletal muscle structure and function. The FASEB Journal. 2010;24(11):4433–4442. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-159608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ratkevicius A, Joyson A, Selmer I, et al. Serum concentrations of myostatin and myostatin-interacting proteins do not differ between young and sarcopenic elderly men. Journals of Gerontology. 2011;66(6):620–626. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrando AA, Stuart CA, Sheffield-Moore M, Wolfe RR. Inactivity amplifies the catabolic response of skeletal muscle to cortisol. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;84(10):3515–3521. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carballo-Jane E, Pandit S, Santoro JC, et al. Skeletal muscle: a dual system to measure glucocorticoid-dependent transactivation and transrepression of gene regulation. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2004;88(2):191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sacheck JM, Ohtsuka A, McLary SC, Goldberg AL. IGF-I stimulates muscle growth by suppressing protein breakdown and expression of atrophy-related ubiquitin ligases, atrogin-1 and MuRF1. American Journal of Physiology. 2004;287(4):E591–E601. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00073.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dardevet D, Sornet C, Taillandier D, Savary I, Attaix D, Grizard J. Sensitivity and protein turnover response to glucocorticoids are different in skeletal muscle from adult and old rats. Lack of regulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway in aging. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;96(5):2113–2119. doi: 10.1172/JCI118264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Savary I, Debras E, Dardevet D, et al. Effect of glucocorticoid excess on skeletal muscle and heart protein synthesis in adult and old rats. British Journal of Nutrition. 1998;79(3):297–304. doi: 10.1079/bjn19980047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rieu I, Sornet C, Grizard J, Dardevet D. Glucocorticoid excess induces a prolonged leucine resistance on muscle protein synthesis in old rats. Experimental Gerontology. 2004;39(9):1315–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ershler WB, Keller ET. Age-associated increased interleukin-6 gene expression, late-life diseases, and frailty. Annual Review of Medicine. 2000;51:245–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krabbe KS, Pedersen M, Bruunsgaard H. Inflammatory mediators in the elderly. Experimental Gerontology. 2004;39(5):687–699. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cappola AR, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Volpato S, Fried LP. Insulin-like growth factor I and interleukin-6 contribute synergistically to disability and mortality in older women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88(5):2019–2025. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taaffe DR, Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Rowe J, Seeman TE. Cross-sectional and prospective relationships of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein with physical performance in elderly persons: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Journals of Gerontology. 2000;55(12):M709–M715. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.12.m709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamer M, Molloy GJ. Association of C-reactive protein and muscle strength in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age. 2009;31(3):171–177. doi: 10.1007/s11357-009-9097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haddad F, Zaldivar F, Cooper DM, Adams GR. IL-6-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;98(3):911–917. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01026.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kohut ML, McCann DA, Russell DW, et al. Aerobic exercise, but not flexibility/resistance exercise, reduces serum IL-18, CRP, and IL-6 independent of β-blockers, BMI, and psychosocial factors in older adults. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2006;20(3):201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stewart LK, Flynn MG, Campbell WW, et al. The influence of exercise training on inflammatory cytokines and C-reactive protein. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2007;39(10):1714–1719. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31811ece1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feldman HA, Longcope C, Derby CA, et al. Age trends in the level of serum testosterone and other hormones in middle-aged men: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;87(2):589–598. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morley JE, Kaiser FE, Perry HM, et al. Longitudinal changes in testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone in healthy older men. Metabolism. 1997;46(4):410–413. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morley JE, Perry HM. Androgens and women at the menopause and beyond. Journals of Gerontology. 2003;58(5):M409–M416. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.5.m409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Urban RJ, Bodenburg YH, Gilkison C, et al. Testosterone administration to elderly men increases skeletal muscle strength and protein synthesis. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269(5):E820–E826. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.269.5.E820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhasin S, Woodhouse L, Storer TW. Proof of the effect of testosterone on skeletal muscle. Journal of Endocrinology. 2001;170(1):27–38. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1700027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bakhshi V, Elliott M, Gentili A, Godschalk M, Mulligan T. Testosterone improves rehabilitation outcomes in ill older men. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(5):550–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb05002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferrando AA, Sheffield-Moore M, Yeckel CW, et al. Testosterone administration to older men improves muscle function: molecular and physiological mechanisms. American Journal of Physiology. 2002;282(3):E601–E607. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00362.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morley JE, Perry HM., III Androgen deficiency in aging men: role of testosterone replacement therapy. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 2000;135(5):370–378. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2000.106455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Hannoush P, et al. Effect of testosterone treatment on body composition and muscle strength in men over 65 years of age. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;84(8):2647–2653. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.8.5885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhasin S, Calof OM, Storer TW, et al. Drug insight: testosterone and selective androgen receptor modulators as anabolic therapies for chronic illness and aging. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;2(3):146–159. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sinha-Hikim I, Cornford M, Gaytan H, Lee ML, Bhasin S. Effects of testosterone supplementation on skeletal muscle fiber hypertrophy and satellite cells in community-dwelling older men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91(8):3024–3033. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mudali S, Dobs AS. Effects of testosterone on body composition of the aging male. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2004;125(4):297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cadilla RP, Turnbull P. Selective androgen receptor modulators in drug discovery: medicinal chemistry and therapeutic potential. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;6(3):245–270. doi: 10.2174/156802606776173456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Labrie F, Luu-The V, Bélanger A, et al. Is dehydroepiandrosterone a hormone? Journal of Endocrinology. 2005;187(2):169–196. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baulieu EE, Thomas G, Legrain S, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), DHEA sulfate, and aging: contribution of the DHEAge study to a sociobiomedical issue. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(8):4279–4284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dayal M, Sammel MD, Zhao J, Hummel AC, Vandenbourne K, Barnhart KT. Supplementation with DHEA: effect on muscle size, strength, quality of life, and lipids. Journal of Women’s Health. 2005;14(5):391–400. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Geel TACM, Geusen PP, Winkens B, Sels JPJE, Dinant GJ. Measures of bioavailable serum testosterone and estradiol and their relationships with muscle mass, muscle strength and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a cross-sectional study. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2009;160(4):681–687. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iannuzzi-Sucich M, Prestwood KM, Kenny AM. Prevalence of sarcopenia and predictors of skeletal muscle mass in healthy, older men and women. Journals of Gerontology. 2002;57(12):M772–M777. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.12.m772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baumgartner RN, Waters DL, Gallagher D, Morley JE, Garry PJ. Predictors of skeletal muscle mass in elderly men and women. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 1999;107(2):123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roubenoff R. Catabolism of aging: is it an inflammatory process? Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2003;6(3):295–299. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000068965.34812.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brown M. Skeletal muscle and bone: effect of sex steroids and aging. Advances in Physiology Education. 2008;32(2):120–126. doi: 10.1152/advan.90111.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Falk RT, Rossi SC, Fears TR, et al. A new ELISA kit for measuring urinary 2-hydroxyestrone, 16α-hydroxyestrone, and their ratio: reproducibility, validity, and assay performance after freeze-thaw cycling and preservation by boric acid. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2000;9(1):81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Florini JR, Ewton DZ, Coolican SA. Growth hormone and the insulin-like growth factor system in myogenesis. Endocrine Reviews. 1996;17(5):481–517. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-5-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ho KY, Veldhuis JD, Johnson ML, et al. Fasting enhances growth hormone secretion and amplifies the complex rhythms of growth hormone secretion in man. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1988;81(4):968–975. doi: 10.1172/JCI113450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Giustina A, Mazziotti G, Canalis E. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factors, and the skeleton. Endocrine Reviews. 2008;29(5):535–559. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moran A, Jacobs DR, Steinberger J, et al. Association between the insulin resistance of puberty and the insulin-like growth factor-I/growth hormone axis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;87(10):4817–4820. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hermann M, Berger P. Hormonal changes in aging men: a therapeutic indication? Experimental Gerontology. 2001;36(7):1075–1082. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ryall JG, Schertzer JD, Lynch GS. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and weakness. Biogerontology. 2008;9(4):213–228. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Veldhuis JD, Iranmanesh A. Physiological regulation of the human growth hormone (GH)-insulin-like growth factor type I (IGF-I) axis: predominant impact of age, obesity, gonadal function, and sleep. Sleep. 1996;19(10):S221–S224. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.suppl_10.s221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Le Roith D, Bondy C, Yakar S, Liu JL, Butler A. The somatomedin hypothesis. Endocrine Reviews. 2001;22(1):53–74. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.1.0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Andersen NB, Andreassen TT, Orskov H, Oxlund H. Growth hormone and mild exercise in combination increases markedly muscle mass and tetanic tension in old rats. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2000;143(3):409–418. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1430409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Blackman MR, Sorkin JD, Münzer T, et al. Growth hormone and sex steroid administration in healthy aged women and men: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(18):2282–2292. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Giannoulis MG, Sonksen PH, Umpleby M, et al. The effects of growth hormone and/or testosterone in healthy elderly men: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91(2):477–484. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marcell TJ, Harman SM, Urban RJ, Metz DD, Rodgers BD, Blackman MR. Comparison of GH, IGF-I, and testosterone with mRNA of receptors and myostatin in skeletal muscle in older men. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;281(6):E1159–E1164. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.6.E1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ferrucci L, Penninx BWJH, Volpato S, et al. Change in muscle strength explains accelerated decline of physical function in older women with high interleukin-6 serum levels. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50(12):1947–1954. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Philippou A, Maridaki M, Halapas A, Koutsilieris M. The role of the insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) in skeletal muscle physiology. In Vivo. 2007;21(1):45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Butterfield GE, Thompson J, Rennie MJ, Marcus R, Hintz RL, Hoffman AR. Effect of rhGH and rhIGF-I treatment on protein utilization in elderly women. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272(1):E94–E99. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.1.E94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Evans WJ, Paolisso G, Abbatecola AM, et al. Frailty and muscle metabolism dysregulation in the elderly. Biogerontology. 2010;11(5):527–536. doi: 10.1007/s10522-010-9297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dardevet D, Sornet C, Attaix D, Baracos VE, Grizard J. Insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin resistance in skeletal muscles of adult and old rats. Endocrinology. 1994;134(3):1475–1484. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.3.8119189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Martineau LC, Chadan SG, Parkhouse WS. Age-associated alterations in cardiac and skeletal muscle glucose transporters, insulin and IGF-1 receptors, and PI3-kinase protein contents in the C57BL/6 mouse. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 1999;106(3):217–232. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Arvat E, Broglio F, Ghigo E. Insulin-like growth factor I: implications in aging. Drugs and Aging. 2000;16(1):29–40. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200016010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wilkes EA, Selby AL, Atherton PJ, et al. Blunting of insulin inhibition of proteolysis in legs of older subjects may contribute to age-related sarcopenia. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;90(5):1343–1350. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kojima M, Kangawa K. Ghrelin: structure and function. Physiological Reviews. 2005;85(2):495–522. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402(6762):656–660. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dixit VD, Schaffer EM, Pyle RS, et al. Ghrelin inhibits leptin- and activation-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression by human monocytes and T cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;114(1):57–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI21134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Akamizu T, Kangawa K. Ghrelin for cachexia. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia, and Muscle. 2010;1(2):169–176. doi: 10.1007/s13539-010-0011-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nagaya N, Itoh T, Murakami S, et al. Treatment of cachexia with ghrelin in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;128(3):1187–1193. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nagaya N, Moriya J, Yasumura Y, et al. Effects of ghrelin administration on left ventricular function, exercise capacity, and muscle wasting in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110(24):3674–3679. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000149746.62908.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bach MA, Rockwood K, Zetterberg C, et al. The Effects of MK-0677, an oral growth hormone secretagogue, in patients with hip fracture. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(4):516–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(3):266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.DeLuca HF. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;80(6):1689S–1696S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1689S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gloth FM, III, Gundberg CM, Hollis BW, Haddad JG, Tobin JD. Vitamin D deficiency in homebound elderly persons. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274(21):1683–1686. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530210037027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Goldray D, Mizrahi-Sasson E, Merdler C, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients in a general hospital. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1989;37(7):589–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wicherts IS, Van Schoor NM, Boeke AJP, et al. Vitamin D status predicts physical performance and its decline in older persons. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92(6):2058–2065. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Borchers M, Gudat F, Dürmüller U, Stähelin HB, Dick W. Vitamin D receptor expression in human muscle tissue decreases with age. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2004;19(2):265–269. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2004.19.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sato Y, Iwamoto J, Kanoko T, Satoh K. Low-dose vitamin D prevents muscular atrophy and reduces falls and hip fractures in women after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2005;20(3):187–192. doi: 10.1159/000087203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Montero-Odasso M, Duque G. Vitamin D in the aging musculoskeletal system: an authentic strength preserving hormone. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2005;26(3):203–219. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yoshikawa S, Nakamura T, Tanabe H, Imamura T. Osteomalacic myopathy. Endocinological Japan. 1979;26:65–72. doi: 10.1507/endocrj1954.26.supplement_65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sorensen OH, Lund Bi., Saltin B. Myopathy in bone loss of ageing: improvement by treatment with 1α-hydroxycholecalciferol and calcium. Clinical Science. 1979;56(2):157–161. doi: 10.1042/cs0560157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Faulkner KA, Cauley JA, Zmuda JM, et al. Higher 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 concentrations associated with lower fall rates in older community-dwelling women. Osteoporosis International. 2006;17(9):1318–1328. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Flicker L, Mead K, MacInnis RJ, et al. Serum vitamin D and falls in older women in residential care in Australia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(11):1533–1538. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Snijder MB, Van Schoor NM, Pluijm SMF, Van Dam RM, Visser M, Lips P. Vitamin D status in relation to one-year risk of recurrent falling in older men and women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91(8):2980–2985. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Annweiler C, Schott AM, Berrut G, Fantino B, Beauchet O. Vitamin D-related changes in physical performance: a systematic review. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging. 2009;13(10):893–898. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Staehelin HB, et al. Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of vitamin D: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Medical Journal. 2009;339:p. b3692. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ceglia L. Vitamin D and its role in skeletal muscle. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2009;12(6):628–633. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328331c707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dawson-Hughes B. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and functional outcomes in the elderly. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;88(2):537S–540S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.537S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne HW, Suppan K, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Dobnig H. Effects of a long-term vitamin D and calcium supplementation on falls and parameters of muscle function in community-dwelling older individuals. Osteoporosis International. 2009;20(2):315–322. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0662-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Jackson C, Gaugris S, Sen SS, Hosking D. The effect of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) on the risk of fall and fracture: a meta-analysis. Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 2007;100(4):185–192. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Latham NK, Anderson CS, Reid IR. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on strength, physical performance, and falls in older persons: a systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(9):1219–1226. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, et al. Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(18):1815–1822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cesari M, Incalzi RA, Zamboni V, Pahor M, et al. Vitamin D hormone: a multitude of actions potentially influencing the physical function decline in older persons. Geriatrics and Gerontology International. 2011;11(2):133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]