Abstract

Saprospira grandis is a coastal marine bacterium that can capture and prey upon other marine bacteria using a mechanism known as ‘ixotrophy’. Here, we present the complete genome sequence of Saprospira grandis str. Lewin isolated from La Jolla beach in San Diego, California. The complete genome sequence comprises a chromosome of 4.35 Mbp and a plasmid of 54.9 Kbp. Genome analysis revealed incomplete pathways for the biosynthesis of nine essential amino acids but presence of a large number of peptidases. The genome encodes multiple copies of sensor globin-coupled rsbR genes thought to be essential for stress response and the presence of such sensor globins in Bacteroidetes is unprecedented. A total of 429 spacer sequences within the three CRISPR repeat regions were identified in the genome and this number is the largest among all the Bacteroidetes sequenced to date.

Keywords: Saprospira grandis, predatory, RsbR, gliding motility, globin-coupled sensors, rhapidosomes

Introduction

Saprospira grandis is an obligately aerobic, Gram-negative marine bacterium belonging to the family Saprospiraceae and is commonly found in marine littoral sand and coastal zones in various locations around the world [1,2]. First isolated and described by Gross in 1911 [3], both marine and fresh water species of Saprospira have been isolated and studied [1,2,4-8]. It is an unusual bacterium because it can prey upon other bacteria using a mechanism known as ‘ixotrophy’ to obtain nutrients [1]. Members of Saprospiraceae are also known to actively hydrolyze proteins in activated-sludge waste treatment plants [9] and this highlights their role as decomposers in various habitats.

Bacteria of the family Saprospiraceae have been shown to actively prey upon harmful diatoms [10] and cyanobacteria such as Microcystis aeruginosa [11]. Saprospiraceae are also found in an epiphytic bacterial biofilm community that colonizes algal surfaces [12]. This association of Saprospiraceae with marine phytoplankton and algae is of considerable interests as the bacteria may play an active role in controlling harmful algal blooms in oceans. Lysis of cyanobacterial cells by Saprospira species has also been reported in another study and the experiments indicated that the lysis took place through direct cell-to-cell contact and not through bactericidal substances [13]. Another curious feature of S. grandis is the presence of phage-like structures known as “rhapidosomes” [14-18]. Although the rhapidosomes superficially resemble phage particles, bactericidal activities have not been recorded in growth assays and the rhapidosomes appear to be normal components of the cells [15,16].

While bacteria of the genus Saprospira are studied quite extensively, genome information is lacking thus far. Therefore, it is of interest to obtain the complete genome sequence of S. grandis to determine its metabolic potential, predatory lifestyle, and genes that encode proteins involved in rhapidosome formation. Here, we report on the complete genome sequencing and annotation of S. grandis str. Lewin, the first member of the Saprospiraceae family to have its complete genome sequenced. We also performed proteomic experiments to identify the proteins that form rhapidosomes in S. grandis str. Lewin.

Classification and features

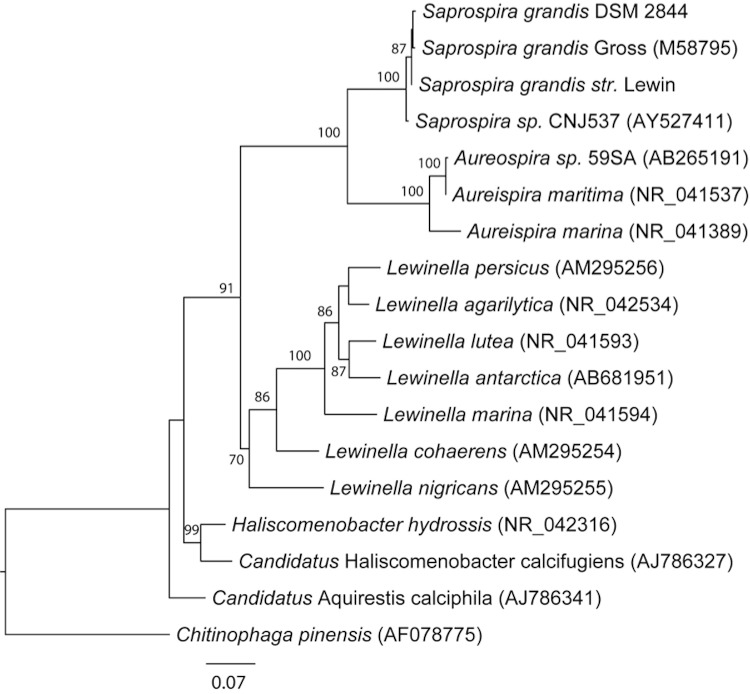

There are three identical copies of the 16S rRNA gene in the Saprospira grandis str. Lewin genome and one copy was chosen to search against the nucleotide database using NCBI BLAST [19]. It has the highest sequence identity to Saprospira grandis SS98-5 (99.7%, AB088636) isolated from Kagoshima Bay, Japan in 1998 [10], 99.4% identity to Saprospira grandis DSM 2844, and 98.0% identity to the type strain Gross [20]. S. grandis DSM 2844 is the only other strain with a draft genome sequence currently available from the Joint Genome Institute (JGI). Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of S. grandis str. Lewin in relation to type and non-type strains within the genus Saprospiraceae. Chitinophaga pinensis was used as an outgroup to root the tree.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of Saprospira grandis strain Lewin relative to other type and non-type strains within the Saprospiraceae. The tree was inferred from 1,350 aligned characters of the 16S rRNA gene sequence using maximum likelihood method. The branch lengths indicate the expected number of substitutions per site and the numbers adjacent to the branches are support values from 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap values are indicated only if they are larger than 60%. Best topology of the tree was inferred by the phylogenetic analysis tool RAxML using GTR (General Time Reversible) model of substitution with the gamma model of rate heterogeneity [21]. Chitinophaga pinensis 16S rRNA gene was used to root the tree.

Saprospira grandis has helical, filamentous cells about 1 μm wide and 5-500 μm long [1]. Individual cells within filaments are about 1-5 μm long [1]. They can grow well at 30ºC but can survive at 40ºC for several hours [2]. S. grandis moves by gliding motility at the speed of 2-5 μm/s [1]. S. grandis is known to be auxotrophic for the following amino acids: arginine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine [2], and prefers nutrients rich in peptides and amino acids [2,8]. Saprospira grandis str. Lewin was originally isolated from La Jolla beach in San Diego, California (Table 1) by the late marine microbiologist Ralph A. Lewin and was a gift to S-I Aizawa [19]. Currently, the strain is not deposited to a culture collection agency but available from the Aizawa lab upon request. We plan to deposit the strain to a culture collection agency as soon as possible. Table 2 presents the project information and associated MIGS version 2.0 identifiers [27].

Table 1. Classification and general features of Saprospira grandis strain Lewin.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Bacteria | TAS [22] | ||

| Phylum Bacteroidetes | TAS [23,24] | ||

| Class Sphingobacteria | TAS [24] | ||

| Current classification | Order Sphingobacteriales | TAS [25] | |

| Family Saprospiraceae | TAS [3] | ||

| Genus Saprospira | TAS [3] | ||

| Species grandis | TAS [3] | ||

| Type strain Gross | TAS [3] | ||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [2,8] | |

| Cell shape | helical filaments | TAS [2,8] | |

| Motility | motile by gliding | TAS [2,8] | |

| Sporulation | no | NAS | |

| Temperature range | 6ºC-47ºC | TAS [2,8] | |

| Optimum temperature | 30ºC | TAS [2] | |

| Carbon source | peptides, proteins | TAS [2,8] | |

| Energy source | chemoorganotroph | TAS [2,8] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | marine littoral zone | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | seawater | TAS [2,8] |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen | strictly aerobic | TAS [2,8] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free-living | IDA |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | not reported | NAS |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | La Jolla beach, San Diego, California, USA | NAS |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | not reported | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | not reported | NAS |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | not reported | NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | sea level | NAS |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | sea level | NAS |

a) Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [26].

Table 2. Project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Three genomic libraries: one Sanger 8kb PE library, one Sanger 3kb PE library, one 454 PE library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | 454 and Sanger |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 30.4× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler, AMOS |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Genemark, PGAAP, manual curation |

| Genome Database release | Genbank | |

| Genbank ID | CP002831 (chromosome) CP002832 (plasmid SGRA01) |

|

| Genbank Date of Release | February 27, 2012 | |

| GOLD ID | Gi10295 | |

| Project relevance | Environmentally relevant heterotrophic marine degrader |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

S. grandis str. Lewin was cultured at 30ºC in seawater medium ( 3% CrystalSea Marine Mix (Marine Enterprises International, Inc.) with 0.5% tryptone). Cells were grown by gentle shaking for 1 day for DNA isolation and 2-3 days for isolation of rhapidosomes. Cells were harvested by low-speed centrifugation and suspended with TE buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.15 M EDTA). Lysozyme, proteinase K, and SDS were gradually added to the suspension and incubated at 37ºC for 30 min. RNaseA was then added to the sample and incubated at 65ºC for 30 min. To purify the genomic DNA, phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (PCI) solution was added to the cell lysate and genomic DNA was collected by ethanol precipitation.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome of S. grandis str. Lewin was sequenced using two different sequencing technologies: capillary-based Sanger sequencing and 454 pyrosequencing. For the Sanger sequencing method, 3-kb and 8-kb shotgun libraries were constructed and the inserts were sequenced from both ends using ABI 3730xl sequencers. A total of 28,669 3-kb and 8,727 8-kb paired-end reads were generated. A total of 378,705 pyrosequences were also generated by the Roche GS FLX system. Sequences from both methods were assembled using Newbler and finishing primers were designed from assembled contig scaffolds. Several rounds of PCR amplification and sequencing using custom-designed primers enabled all the remaining gaps to be closed. Final gaps were manually closed using the Minimus assembler from AMOS package [28] and Seqman II program from DNAStar (DNAstar Inc, Madison, WI). The total sequences covered roughly 30× of the genome.

Genome annotation

Annotation of S. grandis str. Lewin was done using the NCBI PGAAP annotation pipeline [29] and manually checked to improve assignment of protein functions. The pipeline uses Genemark to predict open reading frames (ORFs) and searches against a manually curated list of prokaryotic proteins known as Protein Clusters [30]. Frameshifts and partial gene fragments that indicate potential pseudogenes were identified by the NCBI Submission Check tool and manually verified. Protein coding genes were searched against the NCBI RefSeq database using BLASTp [19]. RPS-BLAST searches against the COG database enabled assignment of COG functional categories to the ORFs. In addition, InterPro searches were also performed using the “iprscan.pl” tool [31,32] to identify conserved domains and protein signatures in each ORF. Ribosomal RNA-coding regions were searched using tRNAscan-SE [33] and Infernal programs [34]. Clustered Regularly Interspersed Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) regions were searched using CRISPR Finder program [35] and predicted protein-coding sequences found within these regions were manually removed. Potential genomic islands were identified using IslandViewer web server [36].

To reconstruct metabolic pathways, the annotated genome in Genbank format was first imported to the Pathway Tools program [37] and pathways were automatically reconstructed. Next, the automatically built pathways in Biopax format were imported to Pathway Studio® software from Ariadne Genomics (Rockville, MD, USA) to manually curate the metabolic pathways. Orthologs of S. grandis str. Lewin proteins in the following 18 bacterial species were identified via reciprocal best BLAST hit (RBH) as reported previously [38]: Clostridium acetobutylicum, Escherichia coli K12, Escherichia coli CFT073, Escherichia coli O157:H7 str. EDL933, Bacillus subtilis, Helicobacter pylori, Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus N315, Pasteurella multocida subsp. multocida str. Pm70, Salmonella typhimurium LT2, Agrobacterium tumefaciens str. C58, Burkholderia xenovorans LB400, Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4, Bordetella pertussis, Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae L20, Flavobacterium johnsoniae UW101, Streptococcus suis 05ZYH33, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Custom-built bacterial genome databases from Pathway Studio and MetaCyc were used as references to manually reconstruct the metabolic pathways in S. grandis str. Lewin. All metabolic pathways were inspected manually to remove functional classes with no members indicating the absence of corresponding enzymatic step(s) in the pathway. Pathways that did not have any gaps after manual curation were considered fully reconstructed.

Genome properties

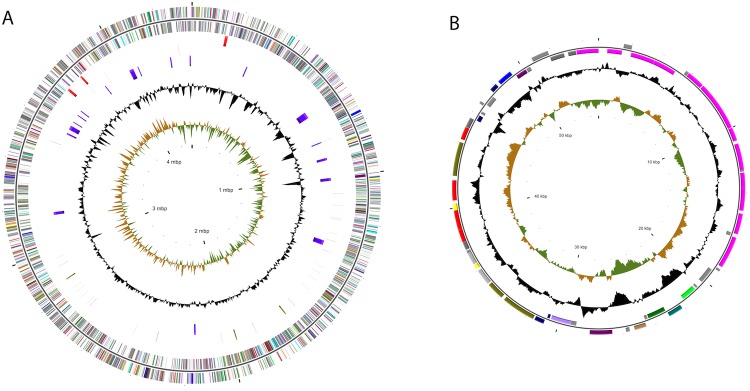

The genome contains a single circular chromosome of 4,345,237 bases and a circular plasmid of 54,948 bases. The circular genomic maps of the S. grandis str. Lewin chromosome and plasmid are shown in Figure 2A and Figure 2B, respectively, and the general genome features are listed in Table 3. The G+C% of the genome is 46.36%. A total of 4,251 ORFs with an average length of 886 bp were predicted. Protein coding genes with known functions account for 50.4% of the genes identified and 34.8% of the gene products have no known function associated with them, i.e., annotated as hypothetical proteins. Conserved hypothetical proteins account for 14.7% of the coding sequences. The distribution of genes into COG functional categories is listed in Table 4. There are 3 ribosomal RNA operons and 48 tRNA genes. The IslandViewer web server predicted 18 putative genomic islands within the genome (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Circular maps of the S. grandis str. Lewin genome. (A) Chromosome. From the inside to outside: GC skew, GC content, genomic islands, rRNA and tRNA coding genes, CRISPR repeat regions, protein coding genes in positive and negative strands colored according to COG categories. (B) Plasmid. From inside to outside: GC skew, GC content, protein coding genes in positive and negative strands colored according to COG categories.

Table 3. Genome statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,345,237 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 3,784,621 | 87.10% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 2,039,994 | 46.36% |

| Number of replicons | 2 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 1 | |

| Total genes | 4,311 | 100.0% |

| RNA genes | 58 | 1.35% |

| rRNA operons | 3 | |

| Pseudogenes | 18 | 0.42% |

| Genes with function prediction | 2,173 | 50.41% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 215 | 5.06% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2,072 | 48.06% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 1,951 | 45.26% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 589 | 13.66% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 778 | 18.05% |

| CRISPR repeats | 3 | % of total |

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %agea | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 160 | 3.7 | Translation |

| A | 0 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 118 | 2.7 | Transcription |

| L | 186 | 4.3 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.02 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 20 | 0.46 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 52 | 1.2 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 91 | 2.1 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 206 | 4.7 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 26 | 0.6 | Cell motility |

| Z | 1 | 0.02 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 44 | 1.0 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 130 | 3.0 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 123 | 2.8 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 64 | 1.5 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 141 | 3.2 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 62 | 1.4 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 89 | 2.1 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 90 | 2.1 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 102 | 2.4 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 52 | 1.2 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 376 | 8.7 | General function prediction only |

| S | 188 | 4.3 | Function unknown |

| - | 2226 | 51.0 | Not in COGs |

a) The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

Clustered regularly interspersed repeats (CRISPRs) and its associated protein modules are a type of immune system present in different bacteria and archaea and is important to protect them from invading viruses and plasmids [39]. Using the CRISPR Finder tool, we identified three confirmed CRISPR repeat regions in the genome and the size of these regions are 11,778 bp, 10,545 bp, and 8,255 bp (Figure 2A). The three CRISPR regions have the following direct repeat consensus sequences: CRISPR region 1 (GTTTCAATGCTGCTTCGCCTGCAAAGGGTTTAGTAT), CRISPR region 2 (ATACTAAACCCATTGCAGGCAAAGCAGCATTGAAAC), and CRISPR region 3 (GTTTCAATGCTGCTTCGCCTGCAAAGGGTTTAGTAT). The numbers of spacers in each of these regions are 165, 148, and 116 for CRISPR regions 1, 2, and 3, respectively, i.e., a total of 429 spacers. Sizes of spacer sequences range from 32 to 76. S. grandis str. Lewin has the largest number of CRISPR spacers among all the Bacteroidetes genomes with identified CRISPR regions and has the second largest number of spacers among all bacteria with CRISPR regions.

The plasmid is 54.9 Kbp long (Figure 2B) and it contains the initiator RepB protein (SGRA_p0025) and plasmid partition protein ParA (SGRA_p0027). Majority of the genes present in the plasmid seem to be involved in metabolic functions rather than virulence. These following genes are involved in nucleotide metabolism: SGRA_p0002 (pyrD), SGRA_p0004 to SGRA_p0005 (guaA and guaB), SGRA_p0007 to SGRA_p0010 (purM, purL, purL, and purH), SGRA_p0012 to SGRA_p0014 (purC, purB, and purD), and SGRA_p0016 to SGRA_p0017 (purN and purF). SGRA_p0039 (paaG), SGRA_p0043 (paaZ), and SGRA_p0044 (paaG) are involved in isoleucine degradation. SGRA_p0042 (fadA) along with the three aforementioned genes are involved in fatty acid oxidation. SGRA_p0023 is involved in tryptophan degradation.

Isolation and purification of rhapidosomes for proteomic analysis

S. grandis str. Lewin cells were cultivated at 30ºC in seawater medium by gentle shaking for 3 days and the cells were harvested by low-speed centrifugation and suspended in sucrose solution (0.5 M sucrose, 0.15 M tris base) by gentle stirring. Lysozyme (final conc. 0.1 mg/ml) and EDTA (final conc. 0.2 mM) were gradually added to the suspension, and the mixture was incubated on ice with gentle stirring. After 60 min of incubation, the cells were lysed with TritonX-100 (final conc. 1%), and the cell debris and nonlysed cells were removed by low-speed centrifugation. To recover rhapidosomes, the supernatant was recentrifuged and resuspended in TET (10 mM Tris/HCl pH8, 1 mM EDTA and 0.1% triton X-100). The samples were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and 2D-gel and each band was analyzed by LC/MS Q-TOF and MALDI-TOF/TOF. The peptide fragments identified were searched against all proteins in the S. grandis str. Lewin genome by BLASTp and also against the genome by tBLASTn.

Insights from the genome

Metabolic pathway reconstruction from the S. grandis str. Lewin genome revealed incomplete pathways for the biosynthesis of nine essential amino acids. This strongly indicates the necessity for external sources of amino acids. A large number of peptidases detected in the genome may facilitate acquisition of supplemental amino acids from the surrounding environments. The genome revealed ten copies of putative globin-coupled sensors. All ten copies of this gene have an N-terminal sensor globin domain and C-terminal STAS domain. Sensor globin-like domains were not identified in any of the Bacteroidetes genomes in our analysis and the presence of this domain and multiple copies of the rsbR gene in the genome are quite intriguing. Out of the ten putative sensor globins, three were experimentally confirmed to be able to bind oxygen, i.e., showed characteristic spectra of globin proteins (data not shown). Top BLASTp hits to all of these rsbR genes are from Vibrio species. We conclude that an rsbR gene was likely acquired from Vibrio species in marine habitats and was later duplicated in the genome. While the exact role of the sensor globin domain in S. grandis is unknown, these RsbR paralogs may be needed for oxygen sensing or in response to oxidative stress.

Biological functions of rhapidosomes are still a mystery despite previous attempts to understand its roles [16-18]. Through the use of genomics and proteomics, we have identified potential proteins that are possibly involved in formation of rhapidosome structures: SGRA_0791, SGRA_1316, and SGRA_1317. SGRA_0791 has a match to Pfam domain “Band_7” which is classified as Stomatin-like integral membrane domain found in all domains of life and also in viruses [40]. SGRA_1316 has a “CHP2241_phage” domain that is usually found in phage tail proteins. SGRA_1317 contains a “Phage_sheath_1” domain. All three proteins can be considered as phage-like proteins but do not seem to be part of a functional phage; they seem to be remnants of horizontally acquired phage genes adapted for as yet unknown functions in S. grandis.

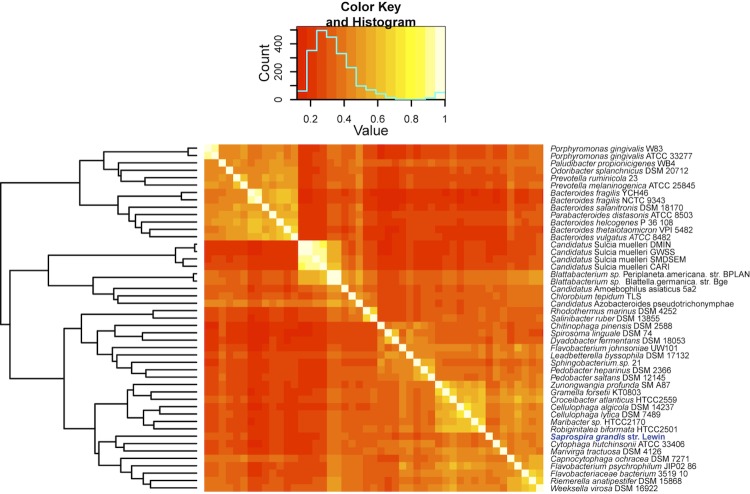

In order to better understand the ecophysiology and phylogeny of S. grandis, we profiled the complete genomes of 46 Bacteroidetes (including S. grandis str. Lewin) and 1 Chlorobi based on 14,228 orthologous groups identified between them. ORFs from these genomes were searched against each other using reciprocal BLAST hit (RBH) method. Orthologous genes shared between the organisms were identified by the Markov Clustering method using OrthoMCL [41,42]. A 14,228 × 47 matrix table based on the presence or absence of these orthologs was then imported to R program [43] and “gplots” package was used to calculate the Pearson correlation and to represent the correlation matrix using a heatmap plot (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Clustered heatmap representations of S. grandis str. Lewin and other completely sequenced Bacteroidetes species based on the presence or absence of 14,228 orthologous genes identified.

Using the orthologous clustering approach, we were able to group different Bacteroidetes with similar physiologies and concluded that S. grandis is closely related to C. hutchinsonii and M. tractuosa in terms of niche specialization and adaptation (Figure 3). Marivirga tractuosa DSM 4126 is also a member of Cytophagales and was isolated from beach sand in Vietnam [44] and is very similar to S. grandis str. Lewin in terms of the niche it occupies. Both also have chitinases to help them utilize chitin from marine eukaryotes. This orthologous gene clustering method is quite a powerful method to classify bacteria based on physiological adaptation and could be useful for characterizing newly isolated bacteria (especially the uncultivated ones) without known physiology.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by U.S. Army Award (TATRC #W81XWH0520013) to M.A. and APEX funding (Malaysia Ministry of Higher Education) to the Centre for Chemical Biology, Universiti Sains Malaysia.

Abbreviations:

- CRISPR

Clustered Regularly Interspersed Repeats

References

- 1.Lewin RA. Saprospira grandis: A flexibacterium that can catch bacterial prey by "Ixotrophy". Microb Ecol 1997; 34:232-236 10.1007/s002489900052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewin FA. Growth and nutrition of Saprospira grandis Gross (Flexibacterales). Can J Microbiol 1972; 18:361-365 10.1139/m72-055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross J. Über freilebende Spironemaceen. Mitt. Zool. Stat. Neapel 1911; 20:188-203 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewin RA. Isolation and some physiological features of Saprospira thermalis. Can J Microbiol 1965; 11:77-86 10.1139/m65-010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewin RA. Freshwater Species of Saprospira. Can J Microbiol 1965; 11:135-139 10.1139/m65-019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewin RA, Lounsbery DM. Isolation, cultivation and characterization of flexibacteria. J Gen Microbiol 1969; 58:145-170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewin RA, Mandel M. Saprospira toviformis nov. spec. (Flexibacterales) from a New Zealand seashore. Can J Microbiol 1970; 16:507-510 10.1139/m70-085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichenbach H. The Genus Saprospira In: Dworkin M, Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K-H., Stackebrandt, E., editor. The Prokaryotes. 3rd ed. Volume 3. New York, NY: Springer; 2006. p 591-601. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia Y, Kong Y, Thomsen TR, Halkjaer Nielsen P. Identification and ecophysiological characterization of epiphytic protein-hydrolyzing saprospiraceae ("Candidatus Epiflobacter" spp.) in activated sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008; 74:2229-2238 10.1128/AEM.02502-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furusawa G, Yoshikawa T, Yasuda A, Sakata T. Algicidal activity and gliding motility of Saprospira sp. SS98-5. Can J Microbiol 2003; 49:92-100 10.1139/w03-017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashton PJ, Robarts RD. Apparent predation of Microcystis aeruginosa Kütz. emend. Elenkin by a Saprospira-like bacterium in a hypertrophic lake (Hartbeespoort Dam, South Africa). J. Limnol. Soc. South Afr. 1987; 13:44-47 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke C, Thomas T, Lewis M, Steinberg P, Kjelleberg S. Composition, uniqueness and variability of the epiphytic bacterial community of the green alga Ulva australis. ISME J 2011; 5:590-600 10.1038/ismej.2010.164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi M, Zou L, Liu X, Gao Y, Zhang Z, Wu W, Wen D, Chen Z, An C. A novel bacterium Saprospira sp. strain PdY3 forms bundles and lyses cyanobacteria. Front Biosci 2006; 11:1916-1923 10.2741/1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Correll DL. Rhapidosomes: 2'-O-methylated ribonucleoproteins. Science 1968; 161:372-373 10.1126/science.161.3839.372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delk AS, Dekker CA. Characterization of rhapidosomes of Saprospira grandis. J Mol Biol 1972; 64:287-295 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90336-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewin RA. Rod-shaped particles in Saprospira. Nature 1963; 198:103-104 10.1038/198103b0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewin RA, Kiethe J. Formation of rhapidosomes in Saprospira. Can J Microbiol 1965; 11:935-938 10.1139/m65-124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reichle RE, Lewin RA. Purification and structure of rhapidosomes. Can J Microbiol 1968; 14:211-213 10.1139/m68-036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:3389-3402 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gherna R, Woese CR. A partial phylogenetic analysis of the "flavobacter-bacteroides" phylum: basis for taxonomic restructuring. Syst Appl Microbiol 1992; 15:513-521 10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80110-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 2006; 22:2688-2690 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Second Edition ed. Volume 1. New York: Springer; 2001. p 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrity GM, Holt JG. Taxonomic Outline of the Archaea and Bacteria In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Second Edition ed. Volume 1. New York: Springer; 2001. p 155-166. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Euzéby JP. List of Bacterial Names with Standing in Nomenclature: a folder available on the Internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:590-592 10.1099/00207713-47-2-590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.<http://sourceforge.net/apps/mediawiki/amos/index.php?title=AMOS>.

- 29.Prokaryotic Genomes Automatic Annotation Pipeline NCBI. (PGAAP). <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/static/Pipeline.html>.

- 30.Protein Clusters <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/proteinclusters>.

- 31.Zdobnov EM, Apweiler R. InterProScan--an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 2001; 17:847-848 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.InterProScan (SOAP) <http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/webservices/services/pfa/iprscan_soap>.

- 33.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 10.1093/nar/25.5.955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffiths-Jones S, Bateman A, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res 2003; 31:439-441 10.1093/nar/gkg006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grissa I, Vergnaud G, Pourcel C. CRISPRFinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35(Web Server issue):W52-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Langille MG, Brinkman FS. IslandViewer: an integrated interface for computational identification and visualization of genomic islands. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:664-665 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karp PD, Paley S, Romero P. The Pathway Tools software. Bioinformatics 2002; 18(Suppl 1):S225-S232 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.S225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ispolatov I, Yuryev A, Mazo I, Maslov S. Binding properties and evolution of homodimers in protein-protein interaction networks. Nucleic Acids Res 2005; 33:3629-3635 10.1093/nar/gki678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Makarova KS, Haft DH, Barrangou R, Brouns SJ, Charpentier E, Horvath P, Moineau S, Mojica FJ, Wolf YI, Yakunin AF, et al. Evolution and classification of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011; 9:467-477 10.1038/nrmicro2577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green JB, Young JP. Slipins: ancient origin, duplication and diversification of the stomatin protein family. BMC Evol Biol 2008; 8:44-55 10.1186/1471-2148-8-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res 2003; 13:2178-2189 10.1101/gr.1224503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Enright AJ, Van Dongen S, Ouzounis CA. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res 2002; 30:1575-1584 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Team RDCR. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nedashkovskaya OI, Vancanneyt M, Kim SB, Bae KS. Reclassification of Flexibacter tractuosus (Lewin 1969) Leadbetter 1974 and 'Microscilla sericea' Lewin 1969 in the genus Marivirga gen. nov. as Marivirga tractuosa comb. nov. and Marivirga sericea nom. rev., comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:1858-1863 10.1099/ijs.0.016121-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]