Abstract

Chromohalobacter salexigens is one of nine currently known species of the genus Chromohalobacter in the family Halomonadaceae. It is the most halotolerant of the so-called ‘moderately halophilic bacteria’ currently known and, due to its strong euryhaline phenotype, it is an established model organism for prokaryotic osmoadaptation. C. salexigens strain 1H11T and Halomonas elongata are the first and the second members of the family Halomonadaceae with a completely sequenced genome. The 3,696,649 bp long chromosome with a total of 3,319 protein-coding and 93 RNA genes was sequenced as part of the DOE Joint Genome Institute Program DOEM 2004.

Keywords: aerobic, chemoorganotrophic, Gram-negative, motile, moderately halophilic, halo tolerant, ectoine synthesis, Halomonadaceae, Gammaproteobacteria, DOEM 2004

Introduction

Strain 1H11T (= DSM 3043 = ATCC BAA-138 = CECT 5384) is the type strain of the species Chromohalobacter salexigens [1], which is one of currently nine species in the genus Chromohalobacter [1,2]. The genus name was derived from the Greek words chroma, color, hals halos, salt, and the Neo-Latin bacter, rod, meaning the colored salt rod. The species epithet originated from the Latin words sal salis, salt, and exigo, to demand; salt-demanding [3]. Strain 1H11T was originally isolated in 1974 in Bonair, Netherlands Antilles, from salterns containing 18.6% salt, and was initially published as a strain belonging to the species Halomonas elongata [4]. In 2001, Arahal et al. transferred the strain to the genus Chromohalobacter [2] as the type strain of the then novel species C. salexigens [1] following detailed phenotypic, genotypic, and phylogenetic analyses. C. salexigens is known for its very broad salinity range [1] and for its role as a model organism for prokaryotic osmosadaptation [5-7], e.g. the synthesis of ectoines (ectoine and hydroxyectoine) for cell stress protection [8,9]. Here we present a summary classification and characteristics of C. salexigens 1H11T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

The sequences of the five identical 16S rRNA genes of strain 1H11T were compared using NCBI BLAST [10] under default settings (e.g., considering only the high-scoring segment pairs (HSPs) from the best 250 hits) with the most recent release of the Greengenes database [11] and the relative frequencies of taxa and keywords (reduced to their stem [12]) were determined and weighted by BLAST scores. The most frequently occurring genera were Halomonas (50.7%), Chromohalobacter (46.3%), 'Haererehalobacter' (1.7%), Bacillus (0.8%) and Pseudomonas (0.5%) (214 hits in total). For 16 hits to sequences from members of the C. salexigens species, the average identity within HSPs was 99.9% and the average coverage by HSPs was 97.9%. For 22 hits to sequences from other members of the genus Chromohalobacter, the average identity within HSPs was 98.2% and the average coverage by HSPs was 98.6%. Among all other species, the one yielding the highest score was Chromohalobacter marismortui (X87222), which corresponded to an identity of 99.9% and an HSP coverage of 100.0%. (Note that the Greengenes database uses the INSDC (= EMBL/NCBI/DDBJ) annotation, which is not an authoritative source for nomenclature or classification.) The highest-scoring environmental sequence was EU799899 ('It's all ranking aquatic Newport Harbor RI clone 1C227569'), which showed an identity of 100.0% and an HSP coverage of 100.0%. The most frequently occurring keywords within the labels of environmental samples which yielded hits were 'soil' (12.1%), 'lake' (3.6%), 'salin' (3.0%), 'agricultur' (2.9%) and 'alkalin, chang, flood, former, mexico, texcoco' (2.6%) (36 hits in total). The most frequently occurring keyword within the labels of environmental samples which yielded hits of a higher score than the highest scoring species was 'aquat, harbour, newport, rank' (25.0%) (2 hits in total). These keywords fit reasonably well with the ecological and physiological properties reported for strain 1H11T in the original description [1].

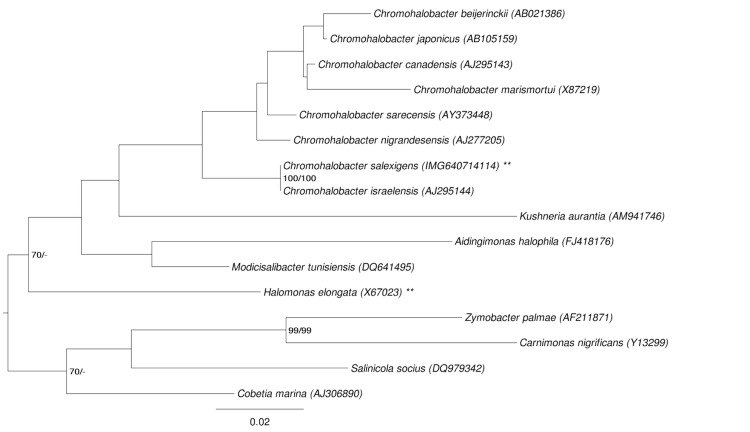

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of C. salexigens in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequences of the five identical 16S rRNA gene copies in the genome differ by two nucleotides from the previously published 16S rRNA sequence (AJ295146), which contains three ambiguous base calls.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of C. salexigens relative to the type strains of the other species within the genus and the type species of the other genera within the family Halomonadaceae. The tree was inferred from 1,440 aligned characters [13,14] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood (ML) criterion [15]. Rooting was done initially using the midpoint method [16] and then checked for its agreement with the current classification (Table 1). The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers adjacent to the branches are support values from 1,000 ML bootstrap replicates [17] (left) and from 1,000 maximum parsimony bootstrap replicates [18] (right) if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [19] are labeled with one asterisk, those also listed as 'Complete and Published' with two asterisks [20].

Table 1. Classification and general features of C. salexigens according to the MIGS recommendations [21].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [22] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [23] | ||

| Class Gammaproteobacteria | TAS [24,25] | ||

| Order Oceanospirillales | TAS [24,26] | ||

| Family Halomonadaceae | TAS [27-31] | ||

| Genus Chromohalobacter | TAS [2,32] | ||

| Species Chromohalobacter salexigens | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain 1H11 | TAS [1,4] | ||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | rod-shaped | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | motile | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | none | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | mesophilic, 15–45°C | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | 37°C | TAS [1] | |

| Salinity | halophilic and halotolerant. Salinity range from 0.9 to 32% (w/v) NaCl in rich media, 2.9% to 19% (0.5 M to 3.75M) NaCl in minimal media; halotolerance increased by osmoprotectants; halotolerance decreases at high temperature. |

TAS [1,4,6,33] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | uses O2 and NO3- as electron acceptors; does not grow fermentatively | TAS [4] |

| Carbon source | various organic acids, alcohols, sugars, and aromatic compounds | TAS [1] | |

| Energy metabolism | chemoorganotrophic | NAS | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | saltern, fresh water | TAS [4] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | none | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [34] | |

| Isolation | solar salt facility, concentration more than 10% NaCl | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Bonaire, Netherlands Antilles | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | June 1974 | TAS [4] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 12.25 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | -68.26 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | surface | NAS |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | sea level | NAS |

Evidence codes - TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e. a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e. not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [35].

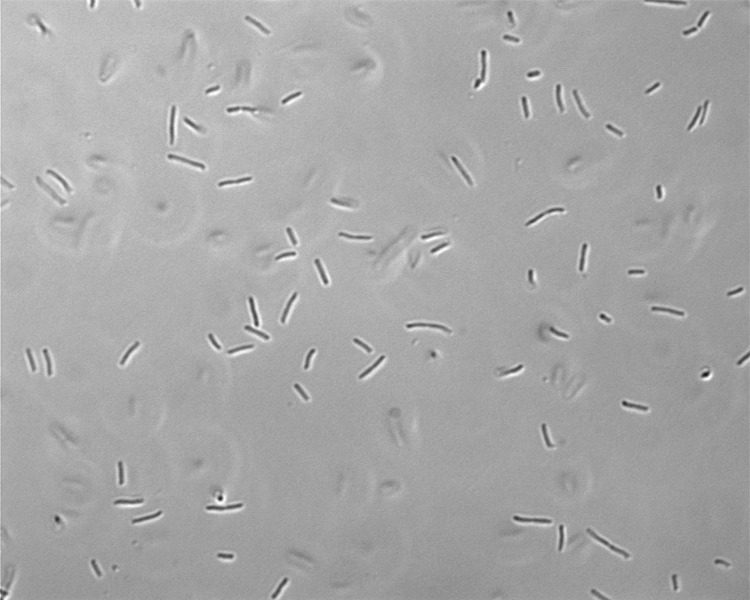

Cells of C. salexigens strain 1H11T are straight or slightly curved rods, 0.7 to 1.0 by 2 to 3 µm in size (Figure 2) with squared ends and occur singly or in pairs [1,4]. Cells of strain 1H11T stain Gram-negative, are motile with polar flagella, strictly aerobic, and are non-spore-forming [1,4]. Carbon and nitrogen source utilization and biochemistry of the strain were reported by Arahal et al. [1]. A partial characterization of the carbon-source utilization by the organism has also been presented by Csonka et al. [36], who reported that the strain can degrade a number of aromatic compounds, including benzoate, protocatechuate, 4-hydroxybenzoate, and toluene.

Figure 2.

Light microscopic image of C. salexigens 1H11T

C. salexigens 1H11T is a halophile, which according to the classification proposed by Kushner [37], is on the borderline between "moderate" halophiles (those growing optimally between 2.9 -14.5% NaCl) and "extreme" halophiles (those growing optimally between 8.7 -23.2% NaCl). In addition, it displays extraordinarily high halotolerance (considered as the ability to live and survive under high salt concentrations), and is able to grow at salt concentrations over 17.4% and 32% in defined and complex media, respectively. However, both the minimum NaCl requirement and the upper limit of NaCl tolerance are dependent on growth medium and temperature. The organism can tolerate higher NaCl concentrations in LB or in other complex media than in defined media. In defined media, halotolerance is enhanced by osmoprotectants, such as glycine betaine or its precursor, choline [4,6,33]. In the complex medium SW (‘sea water’), which is routinely used for growing this type of microorganism, strain 1H11T grows optimally at 7.5 to 10% (w/v) NaCl, with growth occurring over the range of 0.9% to 25% NaCl [1]. In casein medium, which was initially used for strain isolation, growth occurs in the presence of 32% solar salts [4]. In SW medium containing 10% (w/v) total salts, C. salexigens 1H11T can grow at a pH range from 5 to 10, with an optimum at pH 7.5 [1]. In the same medium, the temperature range for growth is 15 – 45°C, with an optimum at 37°C [1]. In the standard defined medium M63, supplemented with glucose as the sole carbon source, growth is optimal at 8.7 to 11.6% NaCl but occurs over the range of 2.9% NaCl or a maximum of 19% NaCl [6]. Interestingly, C. salexigens 1H11T exhibits maximal growth rate in glucose-M63 with only 1.8% (0.3M) NaCl in the presence of high concentrations of salts of other inorganic ions, including K+, Rb+, NH4+, Br-, NO3-, or SO4- [38]. However, it is an open question whether this strain is unique among halophiles in being able to use other inorganic ions in addition to Na+ and Cl- for maximal growth rate.

Chemotaxonomy

Data on the structure of the cell wall, fatty acids lipid composition, quinones and polar lipids are not available.

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of the DOE Joint Genome Institute Program DOEM 2004. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes On Line Database [19] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Three genomic Sanger libraries: 4 kb pUC, 8kb pMCL200 and fosmid pcc1Fos libraries. |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 11.5 × Sanger |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Critica complemented with the output of Glimmer |

| INSDC ID | CP000285 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | April 16, 2006 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc00371 | |

| NCBI project ID | 12636 | |

| Database: IMG | 637000075 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 3043 |

| Project relevance | Bioremediation, Biotechnology, Environmental |

Strain history

The history of strain 1H11T begins with R.H. Vreeland, who deposited the organism in the DSMZ open collection, where cultures of the strain are maintained freeze dried as well as in liquid nitrogen (since 1984). The strain used for the project was provided by the Carmen Vargas – Joaquín Nieto lab in Seville (Spain), who acquired it from the DSMZ.

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

The culture of strain 1H11T, DSM 3043, used to prepare genomic DNA (gDNA) for sequencing was grown in LB medium with 1 M NaCl. DNA was extracted as described by O’Connor and Zusman [39]. The purity, quality and size of the bulk gDNA preparation were assessed by JGI according to DOE-JGI guidelines.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of 4 kb, 8 kb and fosmid DNA libraries. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing can be found at the JGI website [40]. Draft assemblies were based on 44,750 total reads. The Phred/Phrap/Consed software package was used for sequence assembly and quality assessment [41]. After the shotgun stage, reads were assembled with parallel phrap (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher or transposon bombing of bridging clones (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) [42]. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom priming, or PCR amplification (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). A total of 920 additional reactions, 14 shatter and 18 transposon bomb libraries were needed to close gaps and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together all libraries provided 11.5 × coverage of the genome.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using two gene modeling programs, Glimmer [43] and Critica [44] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline. The two sets of gene calls were combined using Critica as the preferred start call for genes with the same stop codon. Genes specifying fewer than 80 amino acids that were predicted by only one of the gene callers and had no Blast hit in the KEGG database at ≤1e-05, were deleted. Automated annotation was followed by a round of manual curation to eliminate obvious overlaps. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) non-redundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. These data sources were combined to assert a product description for each predicted protein. Non-coding genes and miscellaneous features were predicted using tRNAscan-SE [45], TMHMM [46], and signalP [47].

Genome properties

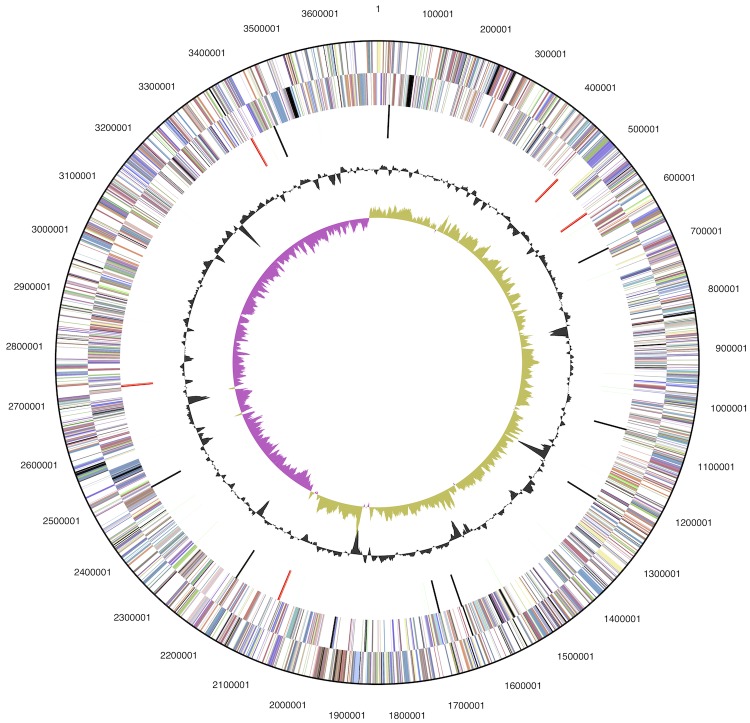

The genome consists of a 3,696,649 bp long chromosome with a 63.9% G+C content (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 3,412 putative genes, 3,319 are protein-coding, and 93 specify RNAs; 21 pseudogenes were also identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (76.8%) were assigned a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as encoding hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3,696,649 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 3,333,410 | 90.17% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 2,362,597 | 63.91% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 3,412 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 93 | 2.73% |

| rRNA operons | 5 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 3,319 | 97.27% |

| Pseudogenes | 21 | 0.62% |

| Genes with function prediction | 2,621 | 76.82% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 402 | 11.78% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2,842 | 83.29% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 2,928 | 85.81% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 689 | 20.19% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 828 | 24.27% |

| CRISPR repeats | 5 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the genome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 166 | 5.2 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 1 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 251 | 7.8 | Transcription |

| L | 114 | 3.5 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 34 | 1.1 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 33 | 1.0 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 152 | 4.7 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 184 | 5.7 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 81 | 2.5 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 77 | 2.4 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 122 | 3.8 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 207 | 6.4 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 227 | 7.1 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 324 | 10.1 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 81 | 2.5 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 152 | 4.7 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 110 | 3.4 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 175 | 5.4 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 76 | 2.4 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 385 | 12.0 | General function prediction only |

| S | 269 | 8.4 | Function unknown |

| - | 570 | 16.7 | Not in COGs |

Insights into the genome

The publication of genome sequence strain 1H11T is preceded by some publications that were based on draft versions of the sequence or on publicly available genome sequence and annotation. Oren et al. [48] found that the predicted isoelectric points of periplasmic proteins of C. salexigens 1H11T are significantly more acidic than those of orthologous proteins in mesophilic bacteria, and they suggested that this feature may contribute to the halophilic characteristics of 1H11T. Analysis of the genomic sequence indicted that the organism has all of the enzymes of the Embden-Meyerhof glycolytic pathway, hexose monophosphate shunt, and TCA cycle but seemed to lack the standard fructose-1,6-bisphosphate phosphatase of the gluconeogenetic pathway [36]. Krejcík et al. predicted the isethionate formation from taurine based on the genome sequence [49]. Ates et al. recently presented a genome-scale reconstruction of a metabolic network for strain 1H11T focusing on the uptake and accumulation of industrially important organic osmolytes such as ectoine and betaine [5].

Acknowledgements

The work conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute was supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

References

- 1.Arahal DR, García MVargas C, Cánovas D, Nieto JJ, Ventosa A. Chromohalobacter salexigens sp. nov., a moderately halophilic species that includes Halomonas elongata DSM 3043 and ATCC 33174. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2001; 51:1457-1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ventosa A, Gutierrez MC, Garcia MT, Ruiz-Berraquero F. Classification of " Chromobacterium marismortui" in a new genus, Chromohalobacter gen. nov., as Chromohalobacter marismortui comb. nov., nom. rev. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1989; 39:382-386 10.1099/00207713-39-4-382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Euzéby JP. List of Bacterial Names with Standing in Nomenclature: a folder available on the Internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:590-592 10.1099/00207713-47-2-590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vreeland RH, Litchfield CD, Martin EL, Elliot E. Halomonas elongata, a new genus and species of extremely salt-tolerant bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:485-495 10.1099/00207713-30-2-485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ates Ö, Oner ET, Arga KY. Genome-scale reconstruction of metabolic network for a halophilic extremophile, Chromobacter salexigens DSM 3043. BMC Syst Biol 2011; 5:12 10.1186/1752-0509-5-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cánovas D, Vargas C, Csonka LN, Ventosa A, Nieto JJ. Osmoprotectants in Halomonas elongata:high affinity betaine transport system and choline-betaine pathway. J Bacteriol 1996; 178:7221-7226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cánovas D, Vargas C, Csonka LN, Ventosa A, Nieto JJ. Synthesis of glycine betaine from exogenous choline in the moderately halophilic bacterium Halomonas elongata Appl Environ Microbiol 1998; 64:4095-4097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pastor JM, Salvador M, Argandona M, Bernal V, Reina-Buena M, Csonka LN, Iborra JL, Vargas C, Nieto JJ, Cánovas M. Ectoines in cell stress protection: uses and biotechnological production. Biotechnol Adv 2010; 28:782-801 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calderón MI, Vargas C, Rojo F, Iglesias-Guerra F, Csonka LN, Ventosa A, Nieto JJ. Complex regulation of the synthesis of the compatible solute ectoine in the halophilic bacterium Chromohalobacter salexigens DSM 3043T. Microbiology 2004; 150:3051-3063 10.1099/mic.0.27122-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 1990; 215:403-410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006; 72:5069-5072 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter MF. An algorithm for suffix stripping. Program: electronic library and information systems 1980; 14:130-137.

- 13.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess PN, De Moraes Russo CA. An empirical test of the midpoint rooting method. Biol J Linn Soc Lond 2007; 92:669-674 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00864.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Moret BME, Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? Lect Notes Comput Sci 2009; 5541:184-200 10.1007/978-3-642-02008-7_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swofford DL. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), Version 4.0 b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The genomes on line database (GOLD) in 2009: Status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwibbert K, Marin-Sanguino A, Bagyan I, Heidrich G, Lentzen G, Seitz H, Rampp M, Schuster SC, Klenk HP, Pfeiffer F, Oesterhelt D, Kunte HJ. A blueprint of ectoine metabolism from the genome of the industrial producer Halomonas elongata DSM 2581T Environ Microbiol 2010; 13:1973-1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms. Proposal for the domains Archaea and Bacteria Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl. nov. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, second edition, vol. 2 (The Proteobacteria), part B (The Gammaproteobacteria), Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class III. Gammaproteobacteria class. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Validation List 106. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005; 55:2235-2238 10.1099/ijs.0.64108-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Order VIII. Oceanospirillales ord. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franzman PD, Wehmeyer U, Stackebrandt E. Halomonadaceae fam. nov., a new family of the class Proteobacteria to accommodate the genera Halomonas and Deleya Syst Appl Microbiol 1988; 11:16-19 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Validation List No 29. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1989; 39:205-206 10.1099/00207713-39-2-205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobson SJ, Franzmann PD. Unification of the genera Deleya (Baumann et al. 1983), Halomonas (Vreeland et al. 1980), and Halovibrio (Fendrich 1988) and the species Paracoccus halodenitrificans (Robinson and Gibbons 1952) into a single genus, Halomonas, and placement of the genus Zymobacter in the family Halomonadaceae. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1996; 46:550-558 10.1099/00207713-46-2-550 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ntougias S, Zervakis GI, Fasseas C. Halotalea alkalilenta gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel osmotolerant and alkalitolerant bacterium from alkaline olive mill wastes, and emended description of the family Halomonadaceae Franzmann et al 1989, emend. Dobson and Franzmann 1996. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:1975-1983 10.1099/ijs.0.65078-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ben Ali Gam Z, Abdelkafi S, Casalot L, Tholozan JL, Oueslati R, Labat M. Modicisalibacter tunisiensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an aerobic, moderately halophilic bacterium isolated from an oilfield-water injection sample, and emended description of the family Halomonadaceae Franzmann et al. 1989 emend Dobson and Franzmann 1996 emend. Ntougias et al 2007. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:2307-2313 10.1099/ijs.0.65088-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arahal DR, García MT, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH, Ventosa A. Transfer of Halomonas canadensis and Halomonas israelensis to the genus Chromohalobacter as Chromohalobacter canadensis comb. nov. and Chromohalobacter israelensis comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2001; 51:1443-1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cánovas D, Vargas C, Csonka LN, Ventosa A, Nieto JJ. Synthesis of glycine betaine from exogenous choline in the moderately halophilic bacterium Halomonas elongata Appl Environ Microbiol 1998; 64:4095-4097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.BAuA. 2010, Classification of bacteria and archaea in risk groups. TRBA 466, p. 56. www.baua.de

- 35.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Csonka LN, O’Connor K, Larimer F, Richardson P, Lapidus A, Ewing AD, Goodner BW, Oren A. What we can deduce about metabolism in the moderate halophile Chromohalobacter salexigens from its genomic sequence. In: Gunde-Cimerman N, Oren A, Plemenitas A (eds). Adaptation to life at high salt concentrations in Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya. 2005. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 267-285. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kushner DJ. Life in high salt and solute concentrations. In: Kushner DJ (ed) Microbial Life in Extreme Environments. London, Academic Press, 1978. pp. 317–368. [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Connor K, Csonka LN. The high salt requirement of the moderate halophile Chromohalobacter salexigens DSM3042 can be met not only by NaCl but by other ions. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003; 69:6334-6336 10.1128/AEM.69.10.6334-6336.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Connor KA. D R Zusman DR. Genetic analysis of tag mutants of Myxococcus xanthus provides evidence for two developmental aggregation systems. J Bacteriol 1990; 172:3868-3878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The DOE Joint Genome Institute www.jgi.doe.gov

- 41.Phrap and Phred for Windows. MacOS, Linux, and Unix. www.phrap.com

- 42.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter JC, Han C, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delcher AL, Bratke K, Powers E, Salzberg S. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 2007; 23:673-679 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Badger JH, Olsen GJ. CRITICA: Coding region identification tool invoking comparative analysis. Mol Biol Evol 1999; 16:512-524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 10.1093/nar/25.5.955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 2001; 305:567-580 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol 2004; 340:783-795 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oren A, Larimer F, Richardson P, Lapidus A, Csonka LN. How to be moderately halophilic with broad salt tolerance: clues from the genome of Chromohalobacter salexigens Extremophiles 2005; 9:275-279 10.1007/s00792-005-0442-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krejcík Z, Hollemeyer K, Smits TH, Cook AM. Isethionate formation from taurine in Chromohalobacter salexigens: purification of sulfoacetaldehyde reductase. Microbiology 2010; 156:1547-1555 10.1099/mic.0.036699-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]