Abstract

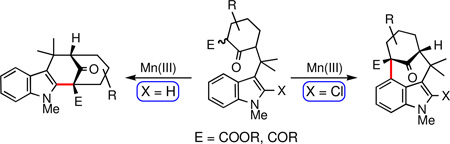

Regiocontrolled oxidative cyclizations of 3-substituted indoles are described herein. Specifically, it is shown that the installation of a chloride at C2 alters the inherent propensity for cyclization at the 2-position of indole so as to favor the 4-position enabling the construction of the unique framework found in most welwitindolinone alkaloids. The chloride functions as more than a blocking group, as it also provides ready access to the corresponding oxindole.

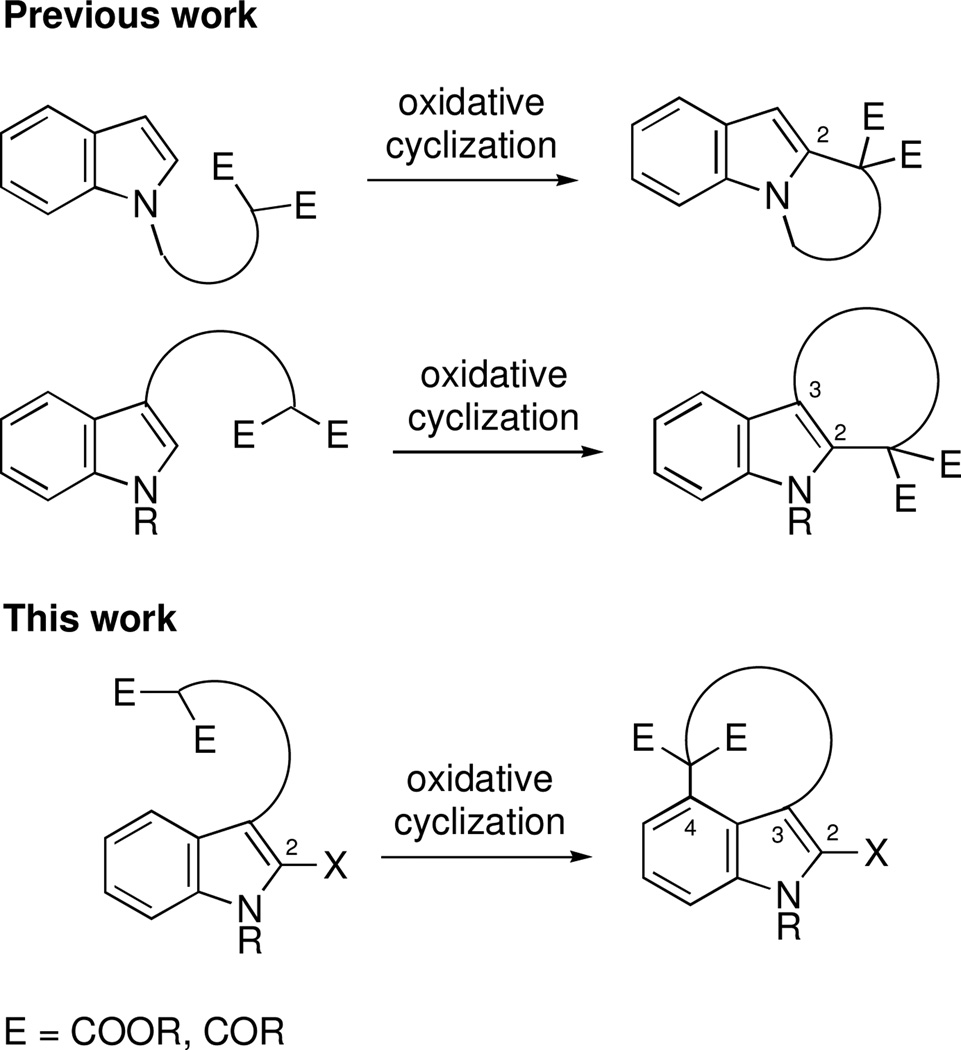

The structural challenges presented by natural products have often stimulated the development of new chemical methods and the exploration of innovative synthetic strategies. For example, the welwitindolinone family of indole alkaloids,1 possessing the unique bicyclo[4.3.1]decane skeleton (Figure 1), has inspired the investigation of numerous creative routes from organic synthesis laboratories around the globe.2 In our own work on these alkaloids, we employed a palladium-catalyzed enolate arylation reaction to construct the carbon framework of the bridged welwitindolinones (5, Scheme 1).3 This strategy proved successful and culminated in the total synthesis of N-methylwelwitindolinone D isonitrile (3).4 The path to the final target was, however, less than straightforward. Indeed, while facing seemingly insurmountable hurdles, we also explored alternate methods for the arylative cyclization to yield the bicyclo[4.3.1]decane ring system. Particularly attractive among these was the possibility of intramolecular oxidative arylation to close the seven-membered ring. An examination of the literature identified the formative work of Muchowski5 and Chuang6 on the intramolecular oxidative cyclizations of pyrroles and indoles bearing a pendant malonyl group. Significant further advances to this area have come from the laboratories of Kerr7 and Li8. What is noteworthy in all these examples is that the tether through which the new ring is formed is attached at either the nitrogen or the C3-position of the indole, such that the newly formed 5, 6, or 7-membered rings are fused to the 1,2- or 2,3-positions of the heterocycles.9 In other words, the cyclization takes place on the pyrrolo-part of the indole, not the benzo-unit. To our knowledge, there appear to be no reports describing intramolecular oxidative cyclizations at the 4-position of indole. The development of such a cyclization pathway would not only extend the scope of these oxidative cyclizations, but it would also generate the sought-after welwitindolinone skeleton (Figure 2).

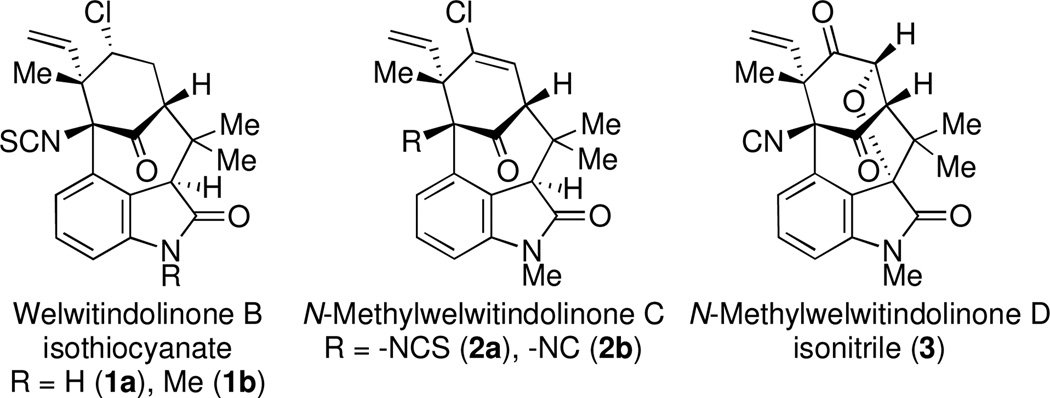

Figure 1.

Representative welwitindolinones alkaloids.

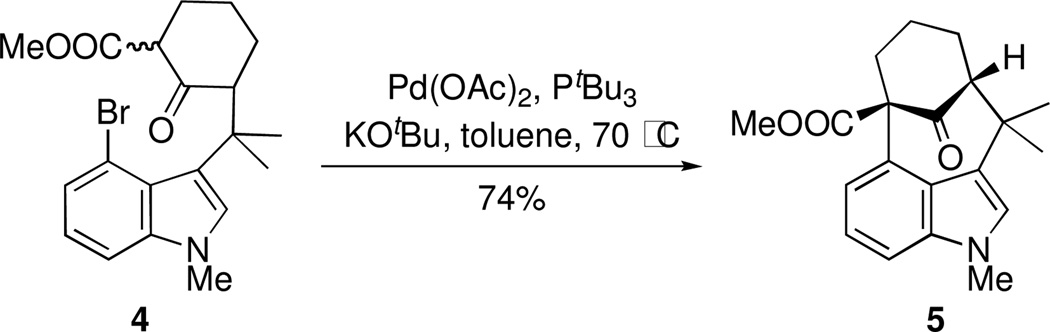

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of welwitindolinone skeleton.a

aSee ref 3.

Figure 2.

Complimentary approach to current methods.

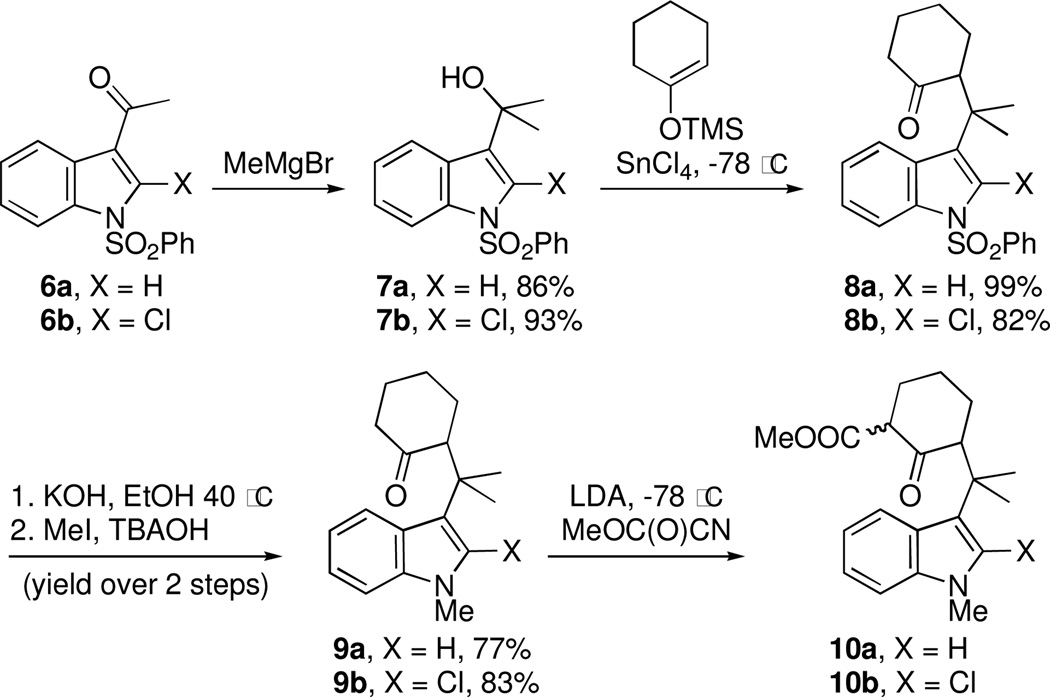

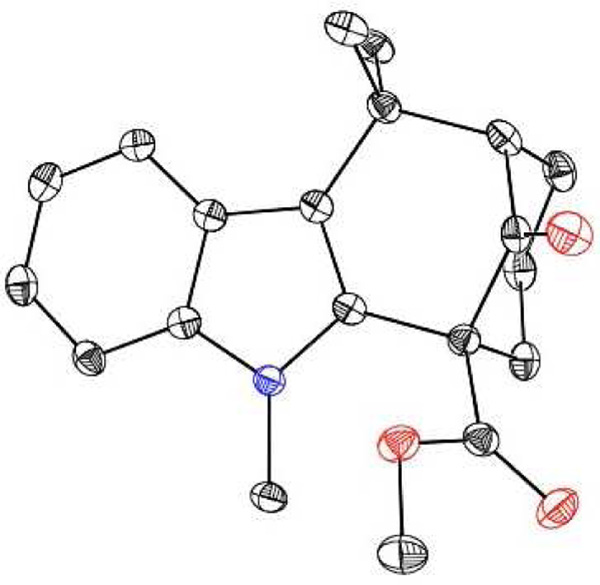

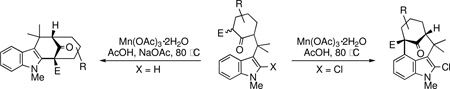

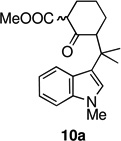

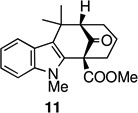

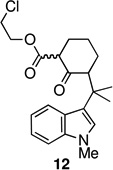

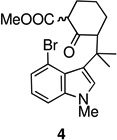

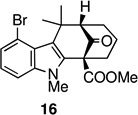

With the welwitindolinones in mind, we examined the oxidative cyclization of several 3-substituted indole derivatives, synthesized by the general route shown in Scheme 2. Thus, ketone 8a was prepared by alkylative coupling of alcohol 7a with the silyl-enol ether of cyclohexanone.3,10 Substitution of the sulfonyl group with the methyl group and carbomethoxylation11 gave the required substrate, 10a. Subjection of ketoester 10a to standard oxidative cyclization conditions12—heating in acetic acid in the presence of Mn(OAc)3—afforded tetracycle 11 cleanly and in high yield (entry 1, Table 1).13 Given the precedents of Kerr and others, we were not surprized to find that the product was tetracycle 11, arising from cyclization at the 2-position of indole. The connectivity present in 11 was unambiguously established through X-ray crystallography (Figure 3).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of cyclization precursors.

Table 1.

Mn(III)-promoted oxidative cyclizations

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | product | time (h) | % yield | entry | substrate | product | time (h) | % yield |

| 1. |  |

|

2 | 82 | 5. |  |

|

3 | 66 |

| 2. |  |

|

5 | 43 | 6. |  |

|

3 | 67 |

| 3. |  |

|

0.75 | 87 | 7. |  |

|

5.5 |

21a, 51 21b, 52 |

| 4. |  |

|

4 | 64 | 8. |  |

|

0.5 | 0a |

Compound 15 was isolated in 34% yield.

Figure 3.

ORTEP image of tetracycle 11.

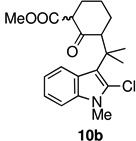

In an effort to overcome the inherent propensity for cyclization at C2, we sought to install a blocking group at this position. The requirements for the blocking group were that it must not only impart steric and electronic deactivation of the 2-position, but it must also withstand the oxidative cyclization conditions and allow future conversion to an oxindole, the functionality found in the welwitindolinones. These requirements appeared to be met by chloride. The necessary 2-chloro-substituted ketoester 10b was prepared through the route outlined in Scheme 2, starting from ketone 6b.14

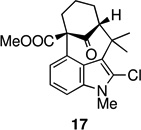

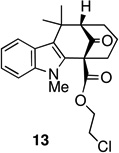

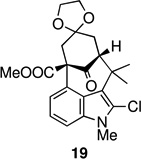

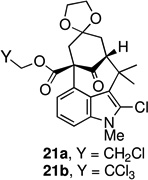

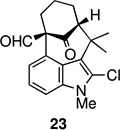

The key oxidative cyclization was carried out using the previously employed conditions, with Mn(OAc)3 as the oxidant. Gratifyingly, the primary product of the reaction was tetracycle 17, obtained in 66% yield, wherein the cyclization had taken place on the benzene ring (entry 5, Table 1). To the best of our knowledge this result represents the first example of an oxidative cyclization onto the 4-position of indole. Up to 10% of the C2-cyclized product (5) was also obtained. The structure assigned to the cyclized product was confirmed through its independent synthesis, by chlorination of tetracyclic ketoester 5, which was prepared by the Pd-catalyzed arylation route.3

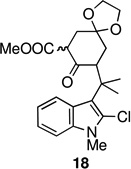

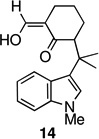

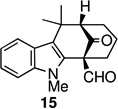

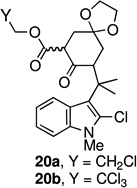

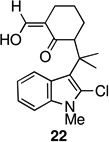

The strategy of modulating regioselectivity by positioning a blocking group at C2 proved to be general and provided good yields of the bicyclo[4.3.1]decane welwitindolinone skeletons with chloride at the 2-position (entries 5–8) and bicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes (entries 1–4) in the absence of chloride at C2. The reaction conditions are tolerant of a variety of functional groups including alkyl chlorides (entries 2 and 7), acetals (entries 6 and 7) and aryl bromides (entry 4). Of particular interest to us was the arylative cyclization of vinylogous acids (i.e., α-formyl ketones), for which there are few precedents in the literature.4,15 To that end, treatment of acid 14 (entry 3) under the standard conditions cleanly furnished the expected cyclization product, 15. Interestingly, the corresponding 2-chlorosubstituted compound (22, entry 8) did not undergo the desired cyclization but, instead, produced the C2-cyclized tetracyclic aldehyde 15 in 34% yield.

A brief solvent study identified acetic acid as the optimum solvent for these reactions, with methanol delivering slightly lower yields. The use of NaOAc as an additive was beneficial for the C2-cyclization reactions (entries 1–4), yet had no advantageous effect on the C4-cyclization substrates (entries 5–8). Other oxidants such as CAN, Mn(pic)3, and Fe(ClO4)3·9H2O gave essentially none of the desired products.

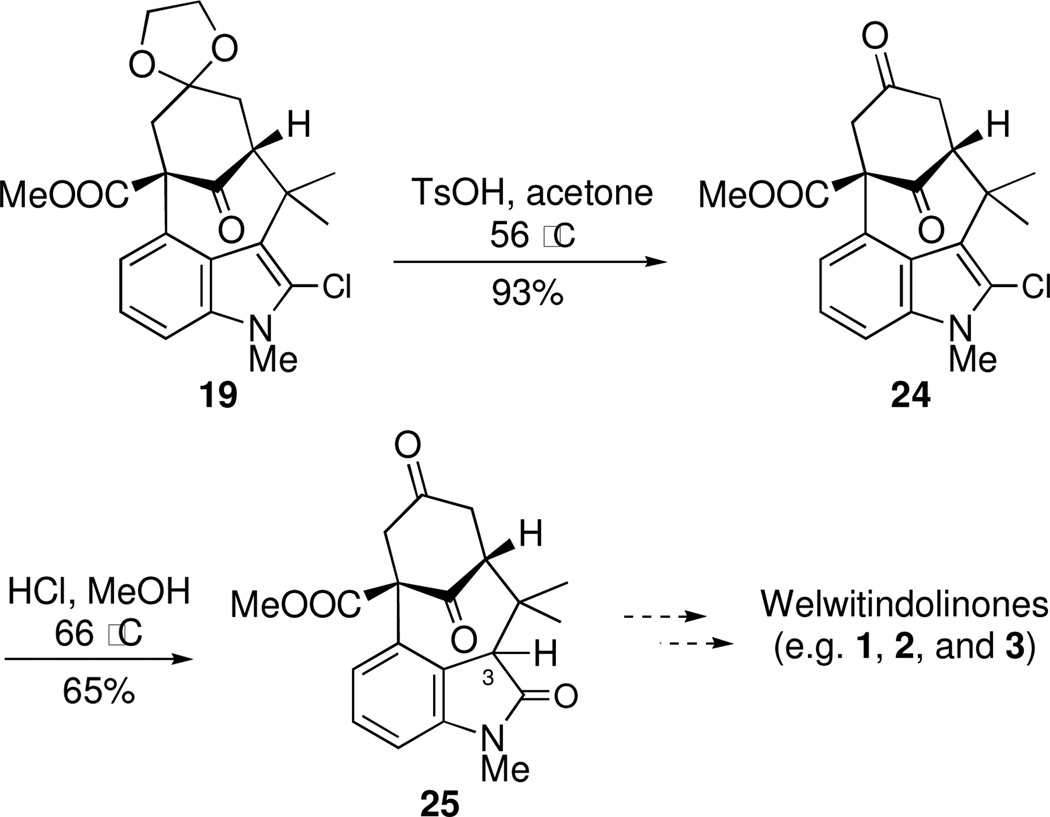

Entries 6 and 7 are of special interest as they represent highly advanced intermediates toward welwitindolinones B, C, and D (1–3). Deprotection of the acetal group in 19 readily yielded the diketone 24 (Scheme 3). The oxindole functionality was then revealed through acidic hydrolysis of 2-chloroindole 24 affording oxindole 25 which is suitably adorned for further elaboration to the aforementioned targets.16

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of oxindole 25.

The results presented above illustrate the possibility of divergent oxidative cyclization reactivity of 3-substituted indoles. Consistent with literature precedent, simple indoles, unsubstituted at the 2-position, undergo selective cyclizations at the 2-position. On the other hand, 2-chloro substituted indoles display altered reactivity, favoring cyclization at the 4-position, on the benzene ring. This simple modification enables the efficient synthesis of the complex bicyclo[4.3.1]decane core of the welwitindolinones. The chloride group at the 2-position is more than just a blocking group, diverting the cyclization to the 4-position; it also provides a handle for further manipulations. The broad functional group tolerance makes this an attractive route toward welwitindolinones and conceivably other intricate indole alkaloids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Generous financial grant from the National Cancer Institute of the NIH (R01 CA101438) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr. I. M. Steele (UChicago) and Dr. A. Jurkiewicz (UChicago) for X-ray crystallographic and NMR spectroscopic assistance, respectively. J.A.M gratefully acknowledges postdoctoral fellowship support (#PF-04-016-01-CDD) from the American Cancer Society.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Full experimental procedures, characterization data, NMR spectra, complete ref 2r, and X-ray crystal data (CIF) for 11. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Stratmann K, Moore RE, Bonjouklian R, Deeter JB, Patterson GML, Shaffer S, Smith CD, Smitka TA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:9935. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jimenez JI, Huber U, Moore RE, Patterson GML. J. Nat. Prod. 1999;62:569. doi: 10.1021/np980485t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For approaches toward welwitindolinone alkaloids, see: Konopelski JP, Deng H, Schiemann K, Keane JM, Olmstead MM. Synlett. 1998:1105. Wood JL, Holubec AA, Stoltz BM, Weiss MM, Dixon JA, Doan BD, Shamji MF, Chen JM, Heffron TP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:6326. Kaoudi T, Ouiclet-Sire B, Seguin S, Zard SZ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:731. Deng H, Konopelski JP. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3001. doi: 10.1021/ol016379r. Jung ME, Slowinski F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:6835. López-Alvarado P, García-Granda S, Àlvarez-Rúa C, Avendaño C. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002:1702. Ready JM, Reisman SE, Hirata M, Weiss MM, Tamaki K, Ovaska TV, Wood JL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:1270. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353282. Baudoux J, Blake AJ, Simpkins NS. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4087. doi: 10.1021/ol051239t. Greshock TJ, Funk RL. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2643. doi: 10.1021/ol0608799. Lauchli R, Shea KJ. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5287. doi: 10.1021/ol0620747. Xia J, Brown LE, Konopelski JP. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:6885. doi: 10.1021/jo071156l. Richter JM, Ishihara Y, Masuda T, Whitefield BW, Llamas T, Pohjakallio A, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:17938. doi: 10.1021/ja806981k. Boissel V, Simpkins NS, Bhalay G, Blake AJ, Lewis W. Chem. Commun. 2009:1398. doi: 10.1039/b820674k. Boissel V, Simpkins NS, Bhalay G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:3283. Tian X, Huters AD, Douglas CJ, Garg NK. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2349. doi: 10.1021/ol9007684. Trost BM, McDougall PJ. Org. Lett. 2009;11:3782. doi: 10.1021/ol901499b. Brailsford JA, Lauchli R, Shea KJ. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5330. doi: 10.1021/ol902173g. Freeman DB, et al. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:6647. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.04.131. Heidebrecht RW, Jr, Gulledge B, Martin SF. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2492. doi: 10.1021/ol1006373. Ruiz M, López-Alvarado P, Menéndez JC. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:4521. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00382d.

- 3.MacKay JA, Bishop RL, Rawal VH. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3421. doi: 10.1021/ol051043t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat V, Allan KM, Rawal VH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5798. doi: 10.1021/ja201834u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artis DR, Cho I-S, Muchowski JM. Can. J. Chem. 1992;70:1838. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Chuang CP, Wang SF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:1283. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsai A-I, Lin C-H, Chuang CP. Heterocycles. 2005;65:2381. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Magolan J, Kerr MA. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4561. doi: 10.1021/ol061698+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Magolan J, Carson CA, Kerr MA. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1437. doi: 10.1021/ol800259s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen P, Cao L, Tian W, Wang X, Li C. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:8436. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03428b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For other methods, see: Tucker JW, Narayanam JMR, Krabbe SW, Stephenson CRJ. Org. Lett. 2010;12:368. doi: 10.1021/ol902703k. Tanaka M, Ubukata M, Matsuo T, Yasue K, Matsumoto K, Kajimoto Y, Ogo T, Inaba T. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3331. doi: 10.1021/ol071336h.

- 10.(a) Muratake H, Natsume M. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:6331. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sakagami M, Muratake H, Natsume M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1994;42:1393. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mander LN, Sethi SP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:5425. [Google Scholar]

- 12.For comprehensive reviews on oxidative cyclization reactions, see: Snider BB. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:339. doi: 10.1021/cr950026m. Snider Barry B. Manganese(III)-Based Oxidative Free-Radical Cyclizations. In: Beller M, Bolm C, editors. Transition Metals for Organic Synthesis. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2004. pp. 483–490.

- 13.For synthesis of structurally similar bicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes, see: Trost BM, Fortunak JMD. Organometallics. 1982;1:7. Butkus E, Berg U, Malinauskiene J, Sandstroem J. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:1353. doi: 10.1021/jo991385a. Butkus E, Malinauskiene J, Stoncius S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003;1:391. doi: 10.1039/b208422h. Baranova TY, Zefirova ON, Averina NV, Boyarskikh VV, Borisova GS, Zyk NV, Zefirov NS. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2007;43:1196.

- 14.See Supporting Information for details.

- 15.(a) Collins DJ, Cullen JD, Fallon GD, Gatehouse BM. Aust. J. Chem. 1984;37:2279. [Google Scholar]; (b) Krawczuk PJ, Schöne N, Baran PS. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4774. doi: 10.1021/ol901963v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oxindole 25 was obtained as a single diastereomer, however, absolute configuration at the C3-position was not determined.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.