Abstract

Stent thrombosis is a potentially lethal complication of percutaneous coronary intervention. We describe the case of a 51-year-old man who presented with acute anterior ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction and underwent successful percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and placement of 3 drug-eluting stents in the left anterior descending coronary artery. Despite receiving dual antiplatelet therapy, the patient presented a week later with a non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction and was found to have nonocclusive thrombosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery stents and his ostial left main and left circumflex coronary arteries. Subsequently, bone marrow biopsy analysis indicated that the patient had acute myelogenous leukemia, which we believe was the underlying cause of his prothrombotic state and stent thrombosis.

Key words: Coronary thrombosis/etiology/prevention & control; hypercoagulability; hyperhomocysteinemia; leukemia, myeloid, acute; leukemia, promyelocytic; Mycobacterium fortuitum; stents/adverse effects; stents, drug-eluting; stents/thrombosis

Acute stent thrombosis is a devastating complication of coronary artery stenting. To prevent stent thrombosis, efforts have been made to optimize the polymer, platform, and drug-elution properties of stents and the use of anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents. However, it is not well understood how leukemia, other cancers, and other potentially prothrombotic disorders might affect the outcome of stent use. We describe the case of a patient with stent thrombosis that occurred in the setting of undiagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia (AML).

Case Report

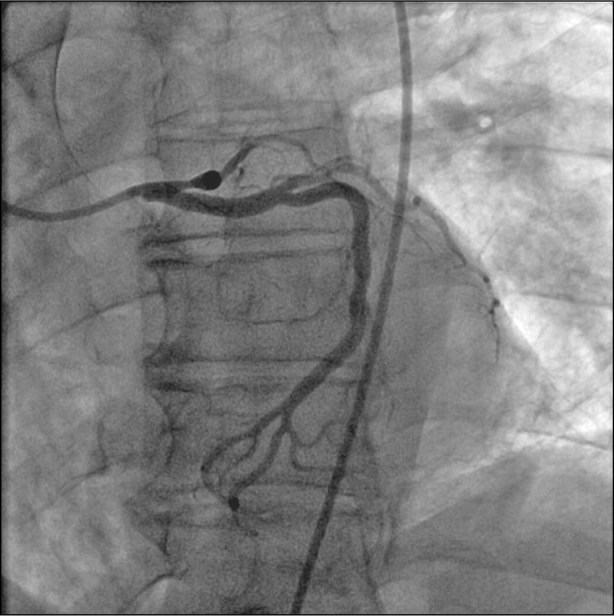

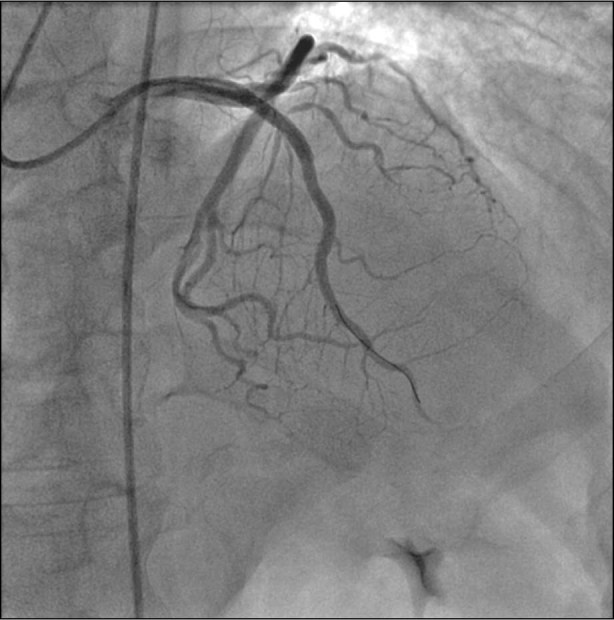

In June 2010, a 51-year-old man with a history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus was admitted to his local hospital after experiencing the sudden onset of chest pain. An anterior ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction was diagnosed. The patient underwent percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and placement of 3 drug-eluting stents in the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) (Figs. 1 and 2). His chest pain and ST-segment changes resolved, and he was discharged from the hospital 4 days after admission, on a regimen of aspirin (81 mg/d) and prasugrel (10 mg/d). Incidentally, he was also found to have pancytopenia (hemoglobin. 12.5 mg/dL; white blood cell count, 3,100/mm3; and platelets, 85,000/mm3), for which no explanation was found before discharge.

Fig. 1 Initial coronary angiogram shows occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery.

Fig. 2 Postprocedural coronary angiogram shows successful intervention. Three drug-eluting stents were deployed in the left anterior descending coronary artery.

Three days later, he returned to the same hospital with recurrent chest pain, elevated cardiac enzyme levels, and hemodynamic instability, but without ST changes on his electrocardiogram. Cardiac catheterization revealed nonocclusive acute thrombosis of the LAD stents and of his ostial left main and left circumflex coronary arteries (Fig. 3). An intra-aortic balloon pump was inserted, and he was transferred to our institution for potential coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

Fig. 3 Coronary angiography performed after the patient's 2nd presentation shows the clot in the proximal left main coronary artery, throughout the stented portion of the left anterior descending coronary artery, and throughout the 2nd obtuse marginal branch of the left circumflex coronary artery.

During preoperative evaluation, the patient was again found to have significant hematologic derangement, including pancytopenia with hemoglobin of 10.1 mg/dL, a white blood cell count of 2,200/mm3, and a platelet count of 33,000/mm3. In addition, he had progressive coagulopathy that was consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation and was characterized by prolonged prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times, decreased platelet and fibrinogen levels, and positive fibrin split products. Before a firm diagnosis could be made, he became hemodynamically unstable and developed anterolateral ST elevations. He was emergently taken to the operating room for CABG.

Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography revealed a superficial excrescence on the mitral valve, so the valve was explored and the excrescence excised for pathologic examination. A left atrial thrombus was discovered and removed. Another thrombus was removed from the ascending aorta. Because the patient was in cardiogenic shock, he could not be weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass and required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation postoperatively.

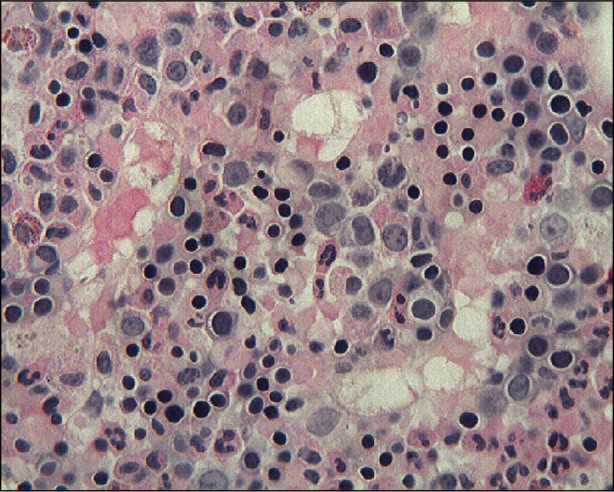

Thirteen days after the patient originally presented at his local hospital, a bone marrow biopsy confirmed that he had AML (Fig. 4). Because of his poor prognosis and worsening cardiovascular status, his family agreed to withdraw supportive care, and the patient died several hours later.

Fig. 4 A bone marrow core biopsy shows increased cellularity (90%) with blasts identified (34%) (H & E, orig. ×400).

Later, his AML was subclassified as acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cytogenetic analysis revealed a t(15;17) (q22;q21) translocation of the leukemic blasts—a classic cytogenetic abnormality. Notably, no Auer rods were found in peripheral blood or bone marrow myeloblasts. In addition, a culture of the mitral valve vegetation excised during surgery grew Mycobacterium fortuitum.

Discussion

We have described the case of a patient with undiagnosed promyelocytic leukemia who had a primary myocardial infarction and, soon thereafter, thrombosis of drug-eluting stents while receiving dual antiplatelet therapy. Because his condition was worsening and unlikely to improve, supportive care was withdrawn, and the patient died.

Spontaneous stent thrombosis is rare, with an incidence of 0.5% to 1.8% in the setting of dual antiplatelet therapy.1,2 Our patient had been taking aspirin and prasugrel—a regimen associated with relatively low rates of stent thrombosis (0.84% during 15 mo).3 Furthermore, simultaneous thrombosis of 2 native coronary vessels, of the stents, and of the left atrium and ascending aorta was an unlikely phenomenon in the absence of thrombophilia. Therefore, we postulate that the patient's AML-related hypercoagulable state was the underlying cause of his cardiovascular events.

Case studies have shown that patients with AML—with or without concurrent disseminated intravascular coagulation—have low levels of antithrombin III and of proteins C and S.4 Our patient's protein C and S levels were markedly decreased (to 20.4% and 27%, respectively). In addition, AML has been associated with hyperhomocysteinemia, another thrombophilic abnormality.5 Our patient also presented with an elevated homocysteine level6 (13.9 µmol/L).

To our knowledge, only 5 other cases of myocardial infarction in the setting of AML have been reported,5 and only singular cases of unexpected in-stent thrombosis in the setting of other hypercoagulable states, such as Factor V Leiden7 or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, have been published.8 An increased incidence of stent thrombosis has been observed in patients with solid tumors, primarily adenocarcinomas.9 In one study, native coronary thrombosis and myocardial infarction heralded the presence of promyelocytic leukemia.10 However, to our knowledge, the English-language literature contains no previous reports of acute drug-eluting stent thrombosis in the setting of AML.

In addition to the interest engendered by its unusual nature, this case raises several questions about the management of acute coronary disease—specifically the use of percutaneous coronary intervention—in patients who have leukemia, other cancers, or other potentially prothrombotic disorders. Malignancy is increasingly recognized as a cause of acute and subacute stent thrombosis8,9,11; other notable causes include stent undersizing and malapposition, dissection, atherosclerotic burden proximal to the stented lesion, lack of aspirin during the procedure, and a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 0.30.11 In addition to their thrombophilia, cancer patients are much more likely to require surgery or experience thrombocytopenia than is the general population, which can complicate the use of antiplatelet therapy. For these and other reasons, some authors have already questioned whether percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting should be used at all to treat stable angina in cancer patients.12 Other questions concern management when percutaneous coronary intervention is indeed indicated, such as in this case. Could a different initial antiplatelet or anticoagulant regimen be beneficial in thrombophilic patients after stent placement? Could bare-metal stents be more beneficial than drug-eluting stents in some cases? Given the increasing incidence of both malignancy and coronary stent use, cases like ours are likely to be seen more frequently in the future and might provide further information regarding differential management and outcomes.

Another highly unusual aspect of this case was the absence of Auer rods in both the bone marrow and the peripheral leukemic blasts of the patient. The literature contains only a handful of reports about promyelocytic-leukemia patients who have exhibited the classic t(15;17)(q22;q21) translocation and the promyelocytic leukemia/retinoic acid receptor-α gene hybrid but have been devoid of Auer rods.13 The absence of such rods in our patient emphasizes the importance of cytogenetic analysis in the diagnosis of AML, which, depending on its subtype, can have very different prognoses and treatments.

A final unusual finding in this patient was the postmortem diagnosis of mitral valve endocarditis due to M. fortuitum. These ubiquitous, fast-growing mycobacteria infrequently cause a wide variety of infections, including infections of soft tissues, surgical wounds, the respiratory tract, the bloodstream, and prosthetic valves.14 However, only 5 cases of native-valve M. fortuitum complex endocarditis have been reported (4 of which were fatal).15-19 Furthermore, our case highlights the fact that M. fortuitum infections in HIV-negative patients are strongly associated with underlying malignancy, especially hematologic cancers.20,21 Although the patient's leukemia was most likely permissive of this rare condition, it is unclear whether the endocarditis and related inflammatory state contributed, in turn, to the thrombotic complications.

Acknowledgment

We thank Nicole Stancel, PhD, ELS, of the Texas Heart Institute at St. Luke's Episcopal Hospital, for editorial assistance with this manuscript.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Surendra K. Jain, MD, 6624 Fannin St., Suite 2320, Houston, TX 77030, E-mail: skj2133@yahoo.com

References

- 1.Cutlip DE, Baim DS, Ho KK, Popma JJ, Lansky AJ, Cohen DJ, et al. Stent thrombosis in the modern era: a pooled analysis of multicenter coronary stent clinical trials. Circulation 2001;103(15):1967–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Mueller C, Roskamm H, Neumann FJ, Hunziker P, Marsch S, Perruchoud A, Buettner HJ. A randomized comparison of clopidogrel and aspirin versus ticlopidine and aspirin after the placement of coronary artery stents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41(6):969–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Horvath I, Keltai M, Herrman JP, et al. Intensive oral antiplatelet therapy for reduction of ischaemic events including stent thrombosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with percutaneous coronary intervention and stenting in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial: a subanalysis of a randomised trial. Lancet 2008;371(9621):1353–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Dixit A, Kannan M, Mahapatra M, Choudhry VP, Saxena R. Roles of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III in acute leukemia. Am J Hematol 2006;81(3):171–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Chang H, Lin TL, Ho WJ, Hsu LA. Acute myeloid leukemia associated with acute myocardial infarction and dural sinus thrombosis: the possible role of leukemia-related hyperhomocysteinemia. J Chin Med Assoc 2008;71(8):416–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Selhub J, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, Rogers G, Bowman BA, Gunter EW, et al. Serum total homocysteine concentrations in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1991–1994): population reference ranges and contribution of vitamin status to high serum concentrations. Ann Intern Med 1999;131(5):331–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Eshtehardi P, Eslami M, Moayed DA. Simultaneous subacute coronary drug-eluting stent thrombosis in two different vessels of a patient with factor V Leiden mutation. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2008;9(4):410–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Muir DF, Stevens A, Napier-Hemy RO, Fath-Ordoubadi F, Curzen N. Recurrent stent thrombosis associated with lupus anticoagulant due to renal cell carcinoma. Int J Cardiovasc Intervent 2003;5(1):44–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Gross CM, Posch MG, Geier C, Olthoff H, Kramer J, Dechend R, et al. Subacute coronary stent thrombosis in cancer patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51(12):1232–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Altwegg SC, Altwegg LA, Maier W. Intracoronary thrombus with tissue factor expression heralding acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Eur Heart J 2007;28(22):2731. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.van Werkum JW, Heestermans AA, Zomer AC, Kelder JC, Suttorp MJ, Rensing BJ, et al. Predictors of coronary stent thrombosis: the Dutch Stent Thrombosis Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53(16):1399–409. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Krone RJ. Managing coronary artery disease in the cancer patient. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2010;53(2):149–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kaleem Z, Watson MS, Zutter MM, Blinder MA, Hess JL. Acute promyelocytic leukemia with additional chromosomal abnormalities and absence of Auer rods. Am J Clin Pathol 1999;112(1):113–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Olalla J, Pombo M, Aguado JM, Rodriguez E, Palenque E, Costa JR, Rioperez E. Mycobacterium fortuitum complex endocarditis-case report and literature review. Clin Microbiol Infect 2002;8(2):125–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Collison SP, Trehan N. Native double-valve endocarditis by Mycobacterium fortuitum following percutaneous coronary intervention. J Heart Valve Dis 2006;15(6):836–8. [PubMed]

- 16.Galil K, Thurer R, Glatter K, Barlam T. Disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection resulting in endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 1996;23(6):1322–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Singh M, Bofinger A, Cave G, Boyle P. Mycobacterium fortuitum endocarditis in a patient with chronic renal failure on hemodialysis. Pathology 1992;24(3):197–200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Spell DW, Szurgot JG, Greer RW, Brown JW 3rd. Native valve endocarditis due to Mycobacterium fortuitum biovar fortuitum: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 2000;30(3):605–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Kuruvila MT, Mathews P, Jesudason M, Ganesh A. Mycobacterium fortuitum endocarditis and meningitis after balloon mitral valvotomy. J Assoc Physicians India 1999;47(10): 1022–3. [PubMed]

- 20.Redelman-Sidi G, Sepkowitz KA. Rapidly growing mycobacteria infection in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51 (4):422–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Raad II, Vartivarian S, Khan A, Bodey GP. Catheter-related infections caused by the Mycobacterium fortuitum complex: 15 cases and review. Rev Infect Dis 1991;13(6):1120–5. [DOI] [PubMed]