Abstract

Objective

To investigate the role of inflammation in the phenotypic expression of myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

Design

Clinical study.

Setting

Kuopio University Hospital and University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland.

Subjects

Twenty-four patients with a single HCM-causing mutation D175N in the α-tropomyosin gene and 17 control subjects.

Main outcome measures

Endomyocardial biopsy samples taken from the patients with HCM were compared with matched myocardial autopsy specimens. Levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and proinflammatory cytokines were measured in patients and controls. Myocardial late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in cardiac MRI (CMRI) was detected.

Results

Endomyocardial samples in patients with HCM showed variable myocyte hypertrophy and size heterogeneity, myofibre disarray, fibrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation. Levels of hsCRP and interleukins (IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-6, IL-10) were significantly higher in patients with HCM than in control subjects. In patients with HCM, there was a significant association between the degree of myocardial inflammatory cell infiltration, fibrosis in histopathological samples and myocardial LGE in CMRI. Levels of hsCRP were significantly associated with histopathological myocardial fibrosis. hsCRP, tumour necrosis factor α and IL-1RA levels had significant correlations with LGE in CMRI.

Conclusions

A variable myocardial and systemic inflammatory response was demonstrated in patients with HCM attributable to an identified sarcometric mutation. Inflammatory response was associated with myocardial fibrosis, suggesting that myocardial fibrosis in HCM is an active process modified by an inflammatory response.

Keywords: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, inflammation, fibrosis, genetics, late gadolinium enhancement, coronary angioplasty, aortic stenosis, invasive cardiology, coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathy hypertrophic, tissue characters, HCM, MRI, myocardial function, myocardial perfusion, myocardial ischaemia, myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, endocrinology

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), most commonly caused by mutations in sarcomeric genes, is a myocardial disease characterised by left ventricular hypertrophy, myocyte disarray and myocardial fibrosis.1 The cardiac phenotype in HCM varies between unrelated individuals and also between family members with an identical disease-causing sarcomeric mutation, suggesting that HCM is a complex inherited disease modified by other genetic and environmental factors.1–5 The molecular events triggered by the genotype or other factors that induce the cardiac phenotype, particularly fibrosis, remain to be determined.4–6

Previous studies have shown that chronic inflammation decreases myocardial contractility, induces hypertrophy and promotes apoptosis and fibrosis, thus contributing to myocardial remodelling.7–9 Inflammatory cytokines, tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα), interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6, are not constitutively expressed in the normal heart, but are upregulated and produced as a stress response to myocardial injury or mechanical stress.8 TNFα and IL-6 can directly attenuate myocardial contractility and induce the development of myocyte hypertrophy, collagen deposition and fibrosis.8 IL-1β has been correlated with myocardial collagen deposition, cardiomyocyte apoptosis and inflammation.10 The expression of both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines is increased in heart failure.9 In addition, nuclear factor κ B (NF-κB), a transcription factor regulating inflammatory genes, has been shown to be activated in patients with heart failure of various causes.11

Circulating inflammatory cytokines are raised in HCM,12–14 but none of the previous studies has investigated the association of cytokine levels with cardiac phenotype determined by cardiac MRI (CMRI). Furthermore, there are no previous studies on NF-κB activation in HCM. Even more importantly, there are few data on myocardial histopathological findings or inflammatory response in patients with HCM caused by a specific sarcomeric gene mutation. Therefore, to investigate the role of inflammation in the phenotypic expression of myocardial fibrosis in HCM, we investigated cardiac histopathology, inflammatory cytokine and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels and cardiac phenotype by CMRI in patients with HCM attributable to an identical HCM-causing mutation D175N in the α-tropomyosin gene (TPM1-D175N).

Patients and methods

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Kuopio University Hospital. All subjects gave written informed consent. Consent to the use of cadaver myocardial samples was obtained from the Finnish Center for Legal Proctection in Health Care. Data of endomyocardial biopsy and cytokine findings have not been published in any form. Previously, we have published studies on CMRI-derived myocardial perfusion, myocardial late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), myocardial contractile impairment and inducibility of life-threatening arrhythmias in this same patient population.2 15–17

Patients with HCM

Twenty-four patients from five Finnish families (11 men, 13 women; mean age, 42±13 years; age range, 17–68 years) with HCM attributable to the mutation D175N in the α-tropomyosin gene (TPM1-D175N)18 19 were included in the study. In Finland, TPM1-D175N is one of the two founder mutations causing about 11% of all, and 25% of familial, HCM cases in eastern Finland.19 Of 24 subjects with TPM1-D175N, two did not meet the diagnostic criteria for clinical HCM and were regarded as healthy mutation carriers. All subjects with TPM1-D175N, however, are called ‘patients with HCM’ in the subsequent analysis. The study protocol described below was performed during one 2-day visit to the Kuopio University Hospital.

Control subjects

Seventeen healthy volunteers not related to patients with HCM and without a previous cardiac disease or drug treatment and with race, gender and age similar to the patients with HCM, were included into our study. Study protocol was identical to that for the patients with HCM, except for cardiac catheterisation and endomyocardial biopsy.

For histopathological analyses, control myocardial specimens were obtained from 20 cadavers matched for age, gender and race without known cardiac disease (no history of a cardiac disease, normal macroscopic myocardial findings and no clear evidence of a specific myocardial disease on microscopic examination).

Clinical and echocardiographic evaluation

All patients with HCM and control subjects underwent an interview, physical examination, 12-lead ECG recording and echocardiography, as previously described.2 15–17

CMRI protocol

CMRI cine, perfusion and LGE imaging were performed in patients with HCM and controls as previously described.2 15 16 CMRI cine imaging was performed in all patients, perfusion imaging in 17 patients with HCM and LGE imaging in 22 patients with HCM.

CMRI image analysis

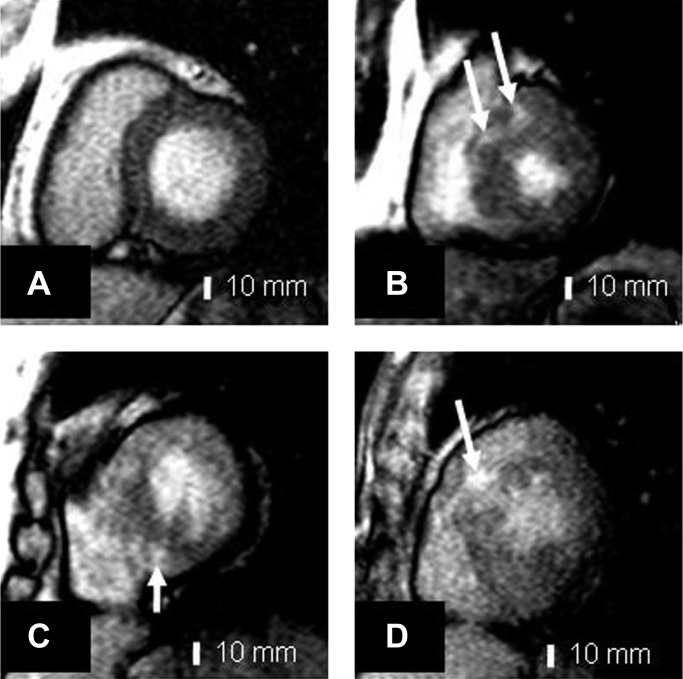

Left ventricular (LV) characteristics and myocardial perfusion by CMRI were evaluated. LGE image analysis was performed in LV short-axis images at the levels of tips of the mitral valve leaflets and papillary muscles.16 In statistical analyses, the maximal value of the six segmental LGE heterogeneity values was used. Figure 1 shows LGE images of one control subject and three patients with HCM.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted inversion recovery images in (A) a 52-year-old control subject; (B) a 45-year-old male patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM); (C) a 37-year-old female patient with HCM; (D) 19-year-old male patient with HCM. Patients with HCM (B–D) show intramyocardial focal high signal areas (arrows) with increased segmental late gadolinium enhancement.

Coronary angiography

Coronary angiography was performed on 21 of 24 patients with HCM using standard angiographic techniques by the same cardiologist (JK).

Endomyocardial biopsy and autopsy myocardial samples

Myocardial specimens for histological analysis and immunohistochemistry were obtained from 20 patients with HCM. Endomyocardial biopsy samples were obtained under fluoroscopic guidance from the right ventricle side of the interventricular septum with the standard endomyocardial bioptome. Control cadaver samples were selected from the archives of the department of clinical pathology of Kuopio University Hospital. Representative myocardial routine autopsy specimens from the anterior, posterior or septal wall of the heart were taken from 20 matched cadavers.

Histological and immunohistochemical methods

Histological methods and immunochemistry analyses are described in detail in the online supplementary information.

Laboratory determinations of cytokines and hsCRP

Plasma concentrations of TNFα, IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β and IL-1RA were measured using assay kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, USA). hsCRP was measured using an Immulite analyser and a DPC hsCRP assay (DPC, Los Angeles, California, USA) in all 24 patients with HCM and in 17 controls.

Statistical analysis

Data are given as mean±SD. Statistical analyses were performed with a statistical software package (SPSS Win V.11.5., SPSS Inc). Because of skewed distribution, LV mass and all cytokines were analysed after logarithmic transformation. The differences between the patients and controls were assessed by Student t test. Mann–Whitney test was used to investigate the association between endomyocardial findings and proinflammatory cytokines. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated to investigate the association of cytokines with LGE in CMRI. Spearman's correlation coefficient was used to investigate the association of different histopathological features, the association between histopathological inflammation and fibrosis and between histopathological inflammation/fibrosis and LGE in CMRI.

Results

Clinical, echocardiographic and CMRI characteristics

Clinical, echocardiographic and CMRI characteristics of the patients with HCM and controls have been published previously2 15–17 and are summarised in table 1. Patients with HCM had stable mild to moderate symptoms (90% of patients had New York Heart Association functional class I–II). None of the subjects with HCM had a history or clinical symptoms or signs of decompensated heart failure, myocarditis, systemic infection, chronic inflammatory disease or life-threatening arrhythmias. None of the patients had an intracardiac defibrillator. About one-third of the patients used cardiac medication, mostly β-blocking agents. None of the patients was taking ACE inhibitors or AT1 receptor antagonists or medication for heart failure.

Table 1.

Clinical, echocardiographic and CMRI characteristics in control subjects and patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

| Characteristics | Control subjects (n=17) | Patients with HCM (n=24) |

| Men/women | 8/9 | 11/13 |

| Age, years | 38±12 | 42±13 |

| Vmax, m/s | 1.3±0.2 | 1.4±0.5 |

| LV MRI findings | ||

| Maximal wall thickness, mm | 9.7±1.7 | 19.5±4.9** |

| Mass, g | 123±32 | 151±57 |

| End-diastolic volume, ml | 146±25 | 122±45** |

| End-systolic volume, ml | 56±15 | 52±29 |

| Hypokinetic segments, % | 12±12 | 37±20** |

| Ejection fraction, % | 61±7 | 58±7 |

| Perfusion reserve | 1.80±0.58 | 1.12±0.35* |

| The heterogeneity of late-enhancement, % | 12±3 | 18±11* |

Vmax indicates maximum velocity in the Doppler signal from the jet in left ventricular outflow tract.

Data are means±SD.

*p<0.05, **p<0.001.

CMRI, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LV, left ventricular.

None of the subjects with HCM had a significant LV outflow tract obstruction (>30 mm Hg) at rest. In CMRI, LV maximal wall thickness was increased in patients with HCM compared with controls. No difference was seen in global LV ejection fraction between patients with HCM and control subjects, but the number of hypokinetic segments was increased in patients with HCM compared with controls.2 The LV perfusion reserve was lower and the maximal LV LGE increased in patients with HCM compared with controls.15 16

Coronary angiography in patients with HCM

Patients with HCM had normal coronary arteries except for one patient with HCM, who had <50% stenosis in the left anterior descending coronary artery and another patient who had <50% stenosis in the left anterior descending, intermediate and right coronary arteries.

Histological findings in endomyocardial samples

Table 2 shows the histopathological findings in haematoxylin–eosin stained endomyocardial samples in patients with HCM. Sufficient endomyocardial biopsy samples for histology were available for 16 of 20 patients with HCM. Histological samples showed variable amounts of heterogeneity of myocyte size, myocyte hypertrophy, myofibre disarray, myocardial fibrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration and intramyocardial small artery narrowing. Interstitial and perivascular fibrosis was found in about 90% of cases. Inflammatory cell infiltration, including mainly mononuclear inflammatory cells and eosinophilic granulocytes, was found in 37% of the patients. Narrowed intramyocardial small arteries were found in one-quarter of the patients. Figure 2 A–C shows typical, mild and marked histopathological findings in patients with HCM, respectively.

Table 2.

Endomyocardial biopsy findings in 16/20 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (haematoxylin-eosin staining)

| Biopsy findings | Number (%) |

| Heterogeneity in myocyte size | |

| No | 3 (19) |

| Moderate | 6 (38) |

| Marked | 7 (44) |

| Myocyte hypertrophy | |

| No | 1 (6) |

| Mild | 11 (69) |

| Moderate | 4 (25) |

| Myofibre disarray | |

| No | 2 (13) |

| Mild | 6 (38) |

| Moderate | 6 (38) |

| Marked | 2 (13) |

| Myocardial fibrosis | |

| No | 2 (13) |

| Mild | 6 (38) |

| Moderate | 6 (38) |

| Marked | 2 (13) |

| Inflammatory cell infiltration* | |

| No | 10 (63) |

| Mild | 4 (25) |

| Moderate | 1 (6) |

| Marked | 1 (6) |

| Intramyocardial small artery narrowing | |

| No | 12 (75) |

| Mild | 2 (13) |

| Moderate | 1 (6) |

| Marked | 1 (6) |

Eosinophilic granulocytes and mononuclear inflammatory cells.

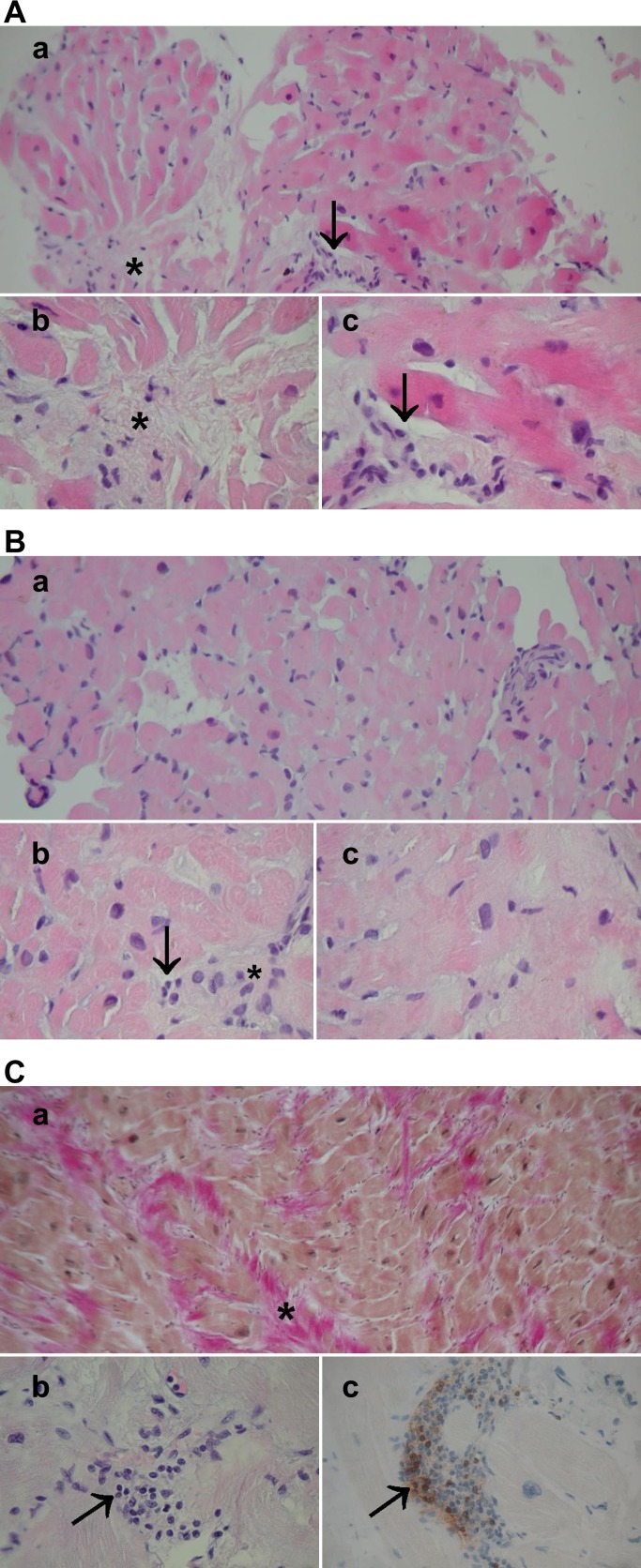

Figure 2.

(A) Typical histopathology in an endomyocardial biopsy of a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). (a) A general view, haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) ×200; (b, c) moderate fibre disarray, interstitial fibrosis (asterisk), moderate myocyte size heterogeneity and hypertrophy and scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells (arrows), H&E ×400, ×630. (B) Mild histopathological findings in a patient with HCM. (a) A general view, H&E ×200; (b, c) mild fibre disarray, fibrosis (asterisk), myocyte hypertrophy and occasional mononuclear inflammatory cells (arrow), H&E ×400, ×630. (C) Severe HCM. (a) A general view: Weigert van Gieson staining highlights marked fibrosis (red, shown by asterisk), ×200; (b) multiple mononuclear inflammatory cells (arrow); (C) showing CD3 positivity in immunohistochemistry (staining in brown, arrow). Original magnification ×400. The patient had severe symptoms, marked left ventricular hypertrophy and inducible ventricular arrhythmia in ventricular stimulation. An intracardiac defibrillator was subsequently implanted.

In control cadaver myocardial samples, mild heterogeneity of myocyte size was found in one of 20 specimens, mild myocyte hypertrophy in seven samples, mild myofibre disarray in one sample, mild interstitial fibrosis in five samples, mild inflammatory cell infiltration of mononuclear cells in one sample and eosinophilic granulocytes and intramyocardial small artery narrowing in none of the samples.

Immunohistochemical findings in endomyocardial samples

Immunostaining with rabbit anti-human antibody showed that seven of 11 (64%) patient endomyocardial biopsy samples had CD3 positivity implicating T-lymphocytes (two with moderate and five with weak positive staining). We could, however, replicate the CD3 positivity with NCL-CD3-PS1 in only one patient endomyocardial biopsy sample showing marked inflammatory response (figure 2C). In 20 control cadaver myocardial samples, weak CD3 positivity with rabbit antihuman antibody was found in two samples and CD3 positivity with NCL-CD3-PS1 in none of the samples. B-lymphocytes with M755 staining were not found in patients or controls. Occasional macrophages with MO814 were found in one patient sample only.

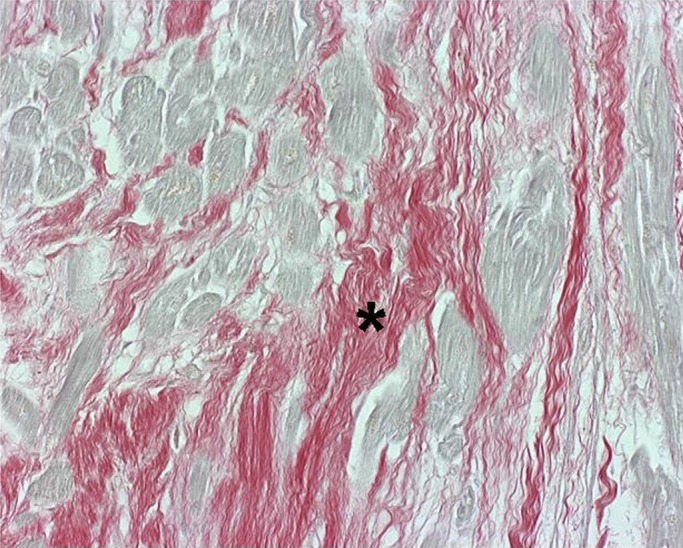

Picrosirius collagen staining was positive in 12 of 15 HCM samples. Extensive fibrosis was found in two cases (figure 3), moderate fibrosis in four cases and mild fibrosis in six cases. In 20 control cadavers, mild fibrosis in Picrosirius staining was found in two cases.

Figure 3.

Endomyocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Increased fibrosis is shown by Picrosirius Red staining (in red, asterisk). Cardiomyocytes are pale yellow stained. Original magnification ×400.

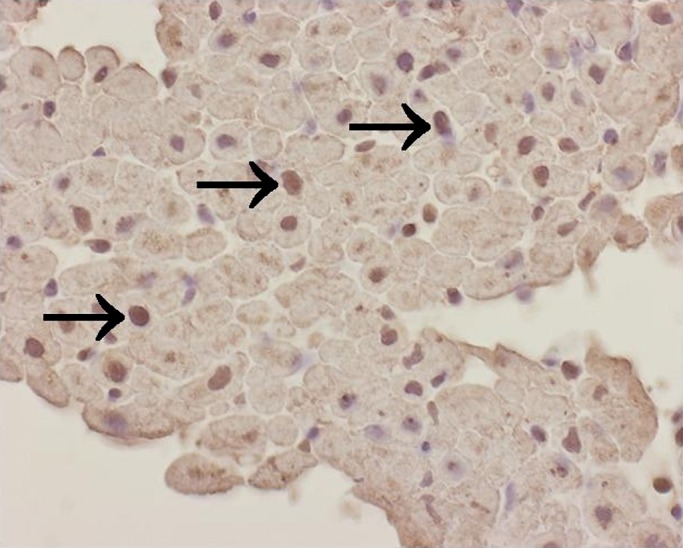

NF-κB nuclear positivity was detected in eight of 15 patient endomyocardial biopsy samples. NF-κB nuclear activity was found in cardiomyocytes in four cases (three cases showed NF-κB positivity in 20–50% of nuclei, one case in 5% of nuclei) (figure 4). In three other cases, nuclear positivity of NF-κB was found in inflammatory cells. Endothelial NF-κB nuclear positivity was found in one case. In control cadaver myocardial specimens, no nuclear NF-κB positivity was detected.

Figure 4.

Nuclear NF- κB activation is detected in cardiomyocytes (arrows) in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. ×400.

Cytokines

Levels of hsCRP, IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-6 and IL-10 were significantly higher in patients with HCM than in control subjects (table 3). There was a trend towards higher TNFα levels in patients with HCM compared with control subjects (p=NS).

Table 3.

Circulating levels of cytokines in control subjects and in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

| Cytokines | Control subjects (n=17) |

Patients with HCM (n=24) |

||

| Mean±SD | Range | Mean±SD | Range | |

| hsCRP, mg/l | 1.29±1.50 | 0.09–5.69 | 4.93±8.38** | 0.33–38.90 |

| TNFα, pg/ml | 2.33±1.22 | 1.38–6.43 | 3.24±−2.98 | 1.56–16.50 |

| IL-1β, pg/ml | 0.18±0.08 | 0.09–0.34 | 0.32±0.25* | 0.09–1.00 |

| IL- 1RA, pg/ml | 216±76 | 101–391 | 490±577** | 194–3023 |

| IL-6, pg/ml | 1.11±0.72 | 0.38–2.80 | 2.15±1.67** | 0.75–7.55 |

| IL-10, pg/ml | 0.86±0.55 | 0.49–2.04 | 2.98±4.04*** | 0.49–20.86 |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-1β, interleukin 1β; IL- 1RA, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist; IL-6, interleukin 6; IL-10, interleukin 10; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor α.

Associations between histopathological myocardial fibrosis, LGE and inflammatory response

In patients with HCM, the degree of histopathological myocardial fibrosis significantly correlated with LGE in CMRI (r=0.568, p=0.034). The grade of myocardial inflammatory cell infiltration correlated with fibrosis in histopathological samples (r=0.614, p=0.011) and with LGE in CMRI (r=0.541, p=0.046).

Levels of hsCRP were significantly associated with histopathological myocardial fibrosis (p<0.05). All other cytokine levels tended to be higher in patients with moderate or marked histopathological findings compared with those with no or mild findings (p=NS, data not shown). Cytokine levels did not correlate significantly with NF-κB activation (data not shown).

Levels of hsCRP, TNFα and IL-1RA significantly correlated with maximal LGE in patients with HCM (table 4). There were no significant associations with IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10 and CMRI-derived maximal LGE. There were no significant associations of cytokine levels with CMRI-derived maximal LV thickness, LV mass, LV diastolic or systolic volumes, global ejection fraction, or myocardial perfusion (data not shown).

Table 4.

The association of circulating cytokine levels with myocardial maximal LGE heterogeneity at mid-ventricular level in patients with HCM (Pearson's correlation coefficients)

| LGE in CMRI | |

| hsCRP, mg/l | 0.517* |

| TNFα, pg/ml | 0.486* |

| IL-1β, pg/ml | 0.032 |

| IL- 1RA, pg/ml | 0.593** |

| IL-6, pg/ml | 0.387 |

| IL-10, pg/ml | 0.038 |

Analysis performed using log 10 transformed values.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01.

CMRI, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-1β, interleukin 1β; IL-1RA, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist; IL-6, interleukin 6; IL-10, interleukin 10; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor α

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that a low-grade myocardial and general inflammatory response is present in HCM attributable to a single well-documented causative sarcomeric mutation (TPM1-D175N). Variable low-grade myocardial inflammation in the patients with HCM was indicated by the presence of myocardial inflammatory cell infiltration and enhanced nuclear NF-κB activity in the myocardium and by increased levels of hsCRP and circulating inflammatory cytokines. Myocardial inflammatory cell infiltration and levels of hsCRP significantly correlated with histopathological myocardial fibrosis and LGE in CMRI and TNFα and IL-1RA correlated with LGE, suggesting that myocardial fibrosis in HCM may be an active process modified by an inflammatory response.

Potential pathogenic mechanism for myocardial fibrosis formation in HCM

Based on our findings we suggest a pathogenic mechanism for myocardial fibrosis formation in HCM. We propose that myocardial fibrosis in HCM is likely to be an active process, in which primary injury—for example, mechanical stress,20 due to disorganised sarcomeric and cellular architecture,21 myocardial ischaemia22 or neuroendocrinological activation,7 induces NF-κB upregulation in the myocardium. NF-κB, in turn, activates production of proinflammatory cytokines, inflammatory cell invasion into the myocardium and activation of fibroblasts, finally leading to myocardial fibrosis.7 8 11

Histopathological myocardial phenotype and the causative mutation in HCM

Endomyocardial samples in our patients with HCM showed variable amounts of myocyte hypertrophy, myocyte size heterogeneity, myofibre disarray, myocardial fibrosis, low-grade inflammatory cell infiltration and intramyocardial small artery narrowing. Transgenic mice carrying a single missense mutation in codon 403 of the myosin heavy-chain gene exhibit variable amounts of histopathological hypertrophy, myocyte disarray, fibrosis and susceptibility to induced arrhythmias.23 In humans, only limited information on histopathological myocardial findings in patients with HCM attributable to an identified sarcomeric mutation has been published.24 As histopathology appears to vary to a great extent in humans and in transgenic animals with identical disease-causing mutations, other factors than the causative mutation necessarily contribute to histopathology in HCM.

Chronic myocardial inflammatory cell infiltration in HCM

Mild to marked interstitial and perivascular inflammatory cell infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory cells, showing CD3 positivity in immunostaining with rabbit anti-human antibody, and of eosinophilic granulocytes, was found in over one-third of histological endomyocardial specimens of the patients with HCM. In one patient with severe HCM, inflammatory cell infiltration was extensive (figure 2C). In contrast, practically no inflammatory cells were recognised in control myocardial samples. Three previous studies have reported that there is mild chronic inflammatory cell infiltration in the myocardium of patients with HCM,3 25 26 but none of them has included genotyped subjects.

Myocardial NF-κB activity in HCM

A new finding in our study was that immunohistochemical staining for nuclear NF-κB activity was positive in half of the endomyocardial samples of patients with HCM. NF-κB activation was detected particularly in cardiomyocytes, but also in inflammatory and endothelial cells. None of the control myocardial samples showed NF-κB activation. NF-κB is a pivotal intracellular mediator of inflammatory response, inducing the proinflammatory cytokine expression.11 NF-κB activation has been previously implicated in cardiac dysfunction and heart failure.11 NF-κB activation leads to proinflammatory phenotype including upregulation of TNFα, which activates inflammatory cell invasion and fibroblasts, resulting in perivascular fibrosis formation in the myocardium.27 Our finding of NF-κB activation in the myocardium of patients with HCM supports the concept that an inflammatory response may play an integral part in the phenotypic expression of myocardial fibrosis in HCM.

Proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in HCM

In this study, both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines were raised in patients with HCM. TNFα levels have been reported to be increased in HCM in some,12 14 but not in all, previous studies.13 IL-6 levels have been shown to be elevated in HCM in two previous studies.13 14 Decreased myocardial TNFα expression has been reported after non-surgical septal reduction in patients with obstructive HCM.28 There are, however, no previous studies evaluating systematically the levels of both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in patients with HCM and particularly, there are no studies correlating levels of cytokines with LGE and other LV characteristics in CMRI.

Clinical implications of the association of inflammatory response with myocardial fibrosis in HCM

CMR-derived LGE reflects collagenous scar formation in HCM.29 The notion that myocardial fibrosis is a potentially modifiable inflammatory process opens interesting clinical implications in preventing cardiovascular events in HCM, as myocardial fibrosis is a major determinant of malignant arrhythmias and end-stage systolic heart failure in HCM and consequently, increases the risk of cardiac death.5 30

Strengths and limitations of the study

We demonstrated for the first time, in a well-defined genotyped patient population with HCM, consistent signs of low-grade myocardial inflammation by serological, histopathological and immunohistochemical methods. We also showed that inflammatory response is associated with myocardial fibrosis, documented by histopathological methods and LGE in CMRI. Yet, there are some limitations to this study. First, the patient population with HCM is of limited size. Human studies including patients with genotype-verified diagnosis of HCM, especially those with a single causative mutation, are, however, few and generally small, as shown by recent studies.31 32 Second, it is possible that the findings of this study may not be applicable to all patients with HCM with different causative mutations in sarcomeric genes. However, myocardial fibrosis is a common manifestation of the HCM, LGE presenting in 80% of cases.1 Furthermore, according to current knowledge, no particular clinical HCM phenotype is mutation specific.5 Probably, the findings of this study apply to HCM caused by other sarcomeric mutations as well, and confirmation of our findings in large genotyped patient populations is warranted. Third, in our CMRI method, severity and not the extent of LGE was measured. However, the method used has been regarded as scientifically valid and shown to be associated with serum amino-terminal propeptide of type III collagen.16 Fourth, cadaver myocardial specimens were used as controls and compared with endomyocardial biopsy findings of patients with HCM, since it is unethical to obtain endomyocardial samples from healthy controls. Fifth, there was a variable number of patient samples in different immunohistochemical analyses, because the second best endomyocardial biopsy sample designated for immunohistochemical stainings was not sufficient for all microscopic slides in every patient (see online supplementary information). Nevertheless, this study is, to our knowledge, the first human study to perform both endomyocardial biopsy and CMRI in genotyped subjects with HCM.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrate that in patients with HCM attributable to an identical disease-causing mutation in the α-tropomyosin gene, myocardial inflammatory cells and enhanced NF-κB activity are present and circulating cytokine and hsCRP levels are increased. This inflammatory response is associated with myocardial fibrosis. Our findings suggest that a low-grade inflammatory response plays a significant role in the phenotypic expression of myocardial fibrosis in HCM.

Key messages.

In patients with HCM attributable to an identical disease-causing mutation in the alpha-tropomyosin gene, myocardial inflammatory cells and enhanced NF-kB activity are commonly present, and circulating cytokine and hs-CRP levels are increased.

This inflammatory response is associated with histopathological and magnetic resonance derived myocardial fibrosis.

Our findings suggest that a low grade inflammatory response plays a significant role in the phenotypic expression of myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have contributed to the article by participating in the design (JK, VK, PS, KPe, KPu, AN, ML, IK, SY), performance of genetic studies (JK, PJ, ML), clinical and echocardiographic studies (JK, KPe), magnetic resonance studies (PS, JK), histological and immunohistochemical studies (JK, VK, AN, IK, SY), laboratory measurements (KPu), drafting the manuscript and approving the final manuscript (all authors). All authors have contibuted to the study design, collection of and/or analysis of the data, writing and/or editing the manuscript and approving the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Academy of Finland and the Finnish Heart Research Foundation (grants to JK.).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Provided by the ethics committee of the Kuopio University Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Elliott P, McKenna WJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet 2004;363:1881–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sipola P, Lauerma K, Jääskelainen P, et al. Cine MR imaging of myocardial contractile impairment in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy attributable to Asp175Asn mutation in the alpha-tropomyosin gene. Radiology 2005;236:815–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamke GT, Allen RD, Edwards WD, et al. Surgical pathology of subaortic septal myectomy associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A study of 204 cases (1996-2000). Cardiovasc Pathol 2003;12:149–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts R, Sigwart U. Current concepts of the pathogenesis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2005;112:293–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keren A, Syrris P, McKenna WJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the genetic determinants of clinical disease expression. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2008;5:158–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cambronero F, Marin F, Roldan V, et al. Biomarkers of pathophysiology in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: implications for clinical management and prognosis. Eur Heart J 2009;30:139–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann DL. Inflammatory mediators and the failing heart: past, present and the foreseeable future. Circ Res 2002;91:988–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nian M, Lee P, Khaper N, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and postmyocardial infarction remodeling. Circ Res 2004;94:1543–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aukrust P, Gullestad L, Ueland T, et al. Inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in chronic heart failure: potential therapeutic implications. Ann Med 2005;37:74–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gullestad L, Aukrust P. Review of trials in chronic heart failure showing broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory approaches. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:17C–23; discussion 38C–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong SC, Fukuchi M, Melnyk P, et al. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 and activation of nuclear factor-kappaB in myocardium of patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation 1998;98:100–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsumori A, Yamada T, Suzuki H, et al. Increased circulating cytokines in patients with myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. Br Heart J 1994;72:561–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogye M, Mandi Y, Csanady M, et al. Comparison of circulating levels of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2004;94:249–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zen K, Irie H, Doue T, et al. Analysis of circulating apoptosis mediators and proinflammatory cytokines in patients with idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: comparison between nonobstructive and dilated-phase hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int Heart J 2005;46:231–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sipola P, Lauerma K, Husso-Saastamoinen M, et al. First-pass MR imaging in the assessment of perfusion impairment in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and the Asp175Asn mutation of the a-tropomyosin gene. Radiology 2003;226:129–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sipola P, Peuhkurinen K, Lauerma K, et al. Myocardial late gadolinium enhancement is associated with raised serum amino-terminal propeptide of type III collagen concentrations in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy attributable to the Asp175Asn mutation in the alpha tropomyosin gene: magnetic resonance imaging study. Heart 2006;92:1321–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedman A, Hartikainen J, Vanninen E, et al. Inducibility of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias is related to maximum left ventricular thickness and clinical markers of sudden cardiac death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy attributable to the Asp175Asn mutation in the a-tropomyosin gene. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2004;36:91–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thierfelder L, Watkins H, MacRae C, et al. Alpha-tropomyosin and cardiac troponin T mutations cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a disease of the sarcomere. Cell 1994;77:701–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jääskeläinen P, Soranta M, Miettinen R, et al. The cardiac beta-myosin heavy chain gene is not the predominant gene for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the Finnish population. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:1709–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang F, Gardner DG. Mechanical strain activates BNP gene transcription through a p38/NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest 1999;104:1603–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. JAMA 2002;287:1308–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maron MS, Olivotto I, Maron BJ, et al. The case for myocardial ischemia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:866–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf CM, Moskowitz IP, Arno S, et al. Somatic events modify hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology and link hypertrophy to arrhythmia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:18123–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coviello DA, Maron BJ, Spirito P, et al. Clinical features of hypertrophic cardiomyopthy cused by mutation of a “hot spot” in the alpha-tropomyosin gene. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;29:635–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baandrup U, Olsen EG. Critical analysis of endomyocardial biopsies from patients suspected of having cardiomyopathy. I: Morphological and morphometric aspects. Br Heart J 1981;45:475–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phadke RS, Vaideeswar P, Mittal B, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an autopsy analysis of 14 cases. J Postgrad Med 2001;47:165–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber KT. From inflammation to fibrosis: a stiff stretch of highway. Hypertension 2004;43:716–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagueh SF, Stetson SJ, Lakkis NM, et al. Decreased expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and regression of hypertrophy after nonsurgical septal reduction therapy for patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2001;103:1844–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moon JC, Reed E, Sheppard MN, et al. The histologic basis of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:2260–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adabag AS, Maron BJ, Appelbaum E, et al. Occurrence and frequency of arrhythmias in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in relation to delayed enhancement on cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1369–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timmer SA, Germans T, Brouwer WP, et al. Carriers of the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy MYBPC3 mutation are characterized by reduced myocardial efficiency in the absence of hypertrophy and microvascular dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;12:1283–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliva-Sandoval MJ, Ruiz-Espejo F, Monserrat L, et al. Insights into genotype-phenotype correlation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Findings from 18 Spanish families with a single mutation in MYBPC3. Heart 2010;96:1980–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.