Abstract

Genomic imprinting causes parental origin–specific monoallelic gene expression through differential DNA methylation established in the parental germ line. However, the mechanisms underlying how specific sequences are selectively methylated are not fully understood. We have found that the components of the PIWI-interacting RNA (piRNA) pathway are required for de novo methylation of the differentially methylated region (DMR) of the imprinted mouse Rasgrf1 locus, but not other paternally imprinted loci. A retrotransposon sequence within a noncoding RNA spanning the DMR was targeted by piRNAs generated from a different locus. A direct repeat in the DMR, which is required for the methylation and imprinting of Rasgrf1, served as a promoter for this RNA. We propose a model in which piRNAs and a target RNA direct the sequence-specific methylation of Rasgrf1.

Imprinted genes show parental origin–specific monoallelic expression, which is controlled by DNA methylation in the differentially methylated regions (DMRs) (1–5). Differential methylation of the DMRs is established in the parental germ line, passed to the zygote, and maintained in the somatic cells, which eventually leads to monoallelic expression. During fetal testis development, the DMRs are demethylated (imprint erasure) in primordial germ cells at 10.5 to 12.5 days postcoitum (dpc) and de novo methylated (establishment) in prospermatogonia or gonocytes at 12.5 to 18.5 dpc (2, 3, 5–7), as retrotransposons (1–3, 5). Of the three well-studied paternally methylated DMRs, the Rasgrf1 DMR is unique in its requirement for the DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3b in both de novo methylation (8) and maintenance methylation (9). Intracisternal A-type particle (IAP) and long interspersed nucleotide element–1 (LINE1 or L1) retrotransposons also require Dnmt3b, as well as PIWI proteins and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), for de novo methylation in the male germ line (7, 10). piRNAs are 24- to 30-nucleotide (nt) small RNAs that bind to PIWI proteins. The PIWI-piRNA complexes (PIWI-piRNAs) repress retrotransposons posttranscriptionally. Of the three mouse PIWI proteins, MILI and MIWI2 are expressed in fetal testes and MIWI in postnatal testes. Because DNA methylation of IAP and L1 retrotransposons is defective in the male germ line of Mili and Miwi2 mutants (7, 10, 11), PIWI-piRNAs may also repress the retrotransposons transcriptionally through DNA methylation.

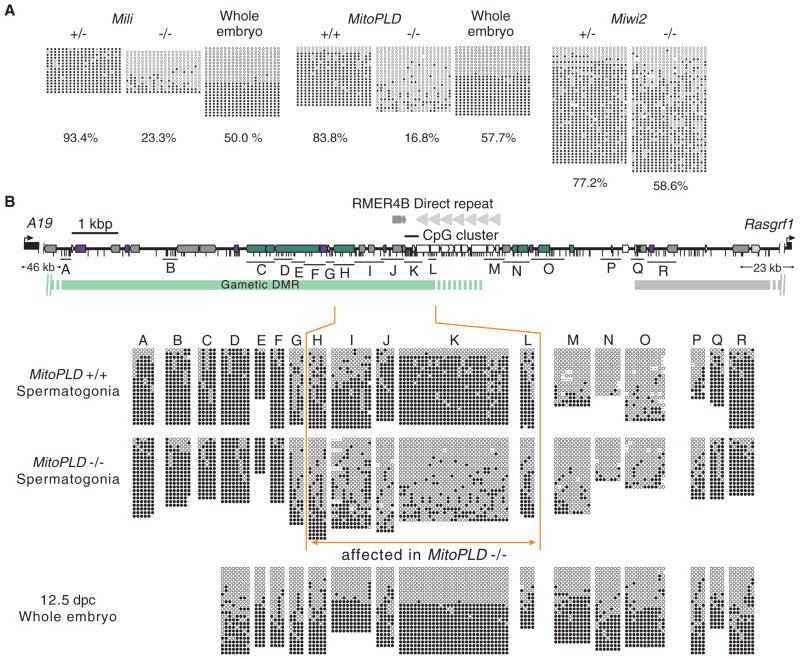

To determine whether PIWI-piRNAs are required for de novo methylation of the DMRs at imprinted loci, we studied mice with mutations in the piRNA pathway. MitoPLD/Zucchini is a protein with a phospholipase D/nuclease domain involved in primary piRNA production in both flies and mice (12–15). The Mili, Miwi2, and MitoPLD mutants show meiotic arrest during spermatogenesis. We analyzed the four paternally methylated DMRs (H19, Dlk1–Gtl2, Gpr1–Zdbf2, and Rasgrf1) in spermatogonia from Mili, Miwi2, and MitoPLD mutant pups by bisulfite sequencing (16). In the mutants, the Rasgrf1 DMR showed reduced methylation (Fig. 1A), whereas the H19, Dlk1–Gtl2, and Gpr1–Zdbf2 DMRs showed normal levels of methylation (figs. S1 and S2). At the Rasgrf1 DMR, methylation was more severely affected in the Mili (23.3% methylation versus 93.4% methylation in control heterozygotes) and MitoPLD mutants (16.8% versus 83.8%) than in the Miwi2 mutants (58.6% versus 77.2%). The Rasgrf1 DMR is located on mouse chromosome 9 (chr9) between Rasgrf1 and the A19 noncoding RNA, both of which are imprinted (17, 18). In the MitoPLD mutants, which showed the severest reduction in piRNAs, an ~2–kilobase (kb) region containing a cluster of CpGs was affected (region H to region L in Fig. 1B). A direct repeat in the Rasgrf1 DMR is known to be essential for methylation and imprinting of Rasgrf1 (19). In the sperm of the direct-repeat deletion mutants, the methylation status of the CpG cluster (corresponding to region K in Fig. 1B) is affected, whereas regions upstream and downstream of the cluster (regions upstream of region F and downstream of region Q in Fig. 1B) are unaffected (19, 20). The extent and pattern of the defect in methylation in the MitoPLD mutants were essentially the same as those in the direct-repeat deletion mutants (19, 20), which suggests that the methylation responsible for Rasgrf1 imprinting is lost in the MitoPLD mutants.

Fig. 1.

DNA methylation of the imprinted Rasgrf1 DMR is impaired in piRNA pathway mutants. (A) Methylation status of a portion of the Rasgrf1 DMR [corresponding to a part of region K in (B)] in spermatogonia from Mili, MitoPLD, and Miwi2 mutants revealed by bisulfite sequencing. Open and filled circles represent unmethylated and methylated cytosines, respectively. A result on 12.5-dpc wild-type whole-embryo DNA is also shown (control, 50% methylation expected). Percentage of methylation is shown below each panel. (B) Methylation status across the Rasgrf1 DMR in MitoPLD mutants. The green and gray bars show the gametic DMRs (regions differentially methylated between oocyte and sperm) (30), of which the green one is important for imprinting. Positions of CpGs are indicated by short vertical bars. Repeat sequences identified by RepeatMasker are shown as colored boxes: green, LINE; purple, short interspersed nucleotide element (SINE); white, simple repeat; gray, LTR; light gray, DNA transposon. A direct repeat consisting of 40 copies of a 41-oligomer (18) and a copy of RMER4B solo LTR are also indicated.

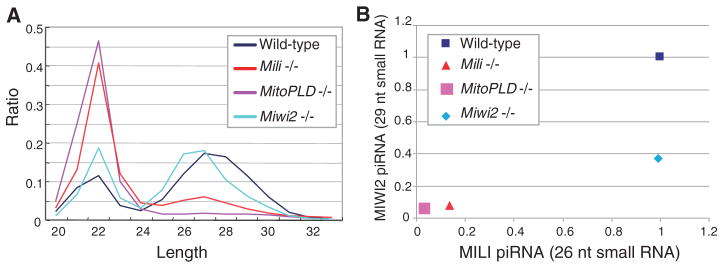

To reveal the effect of the three mutations on piRNA expression, we analyzed small RNA libraries prepared from mutant fetal testes by Solexa deep sequencing (table S1). The relative abundance of 24- to 30-nt piRNAs decreased in all mutants compared with the wild-type control (Fig. 2A). It is known that MIWI2-bound piRNAs are larger in size than MILI-bound piRNAs. In the MitoPLD and Mili mutants, both 26-nt MILI-bound and 29-nt MIWI2-bound piRNAs were present at very low levels (3.4% and 3.5% of the wild-type control and 13.9% and 7.9% of the control, respectively) (Fig. 2B). In the Miwi2 mutants, 26-nt piRNAs were unchanged (99.2% of the control), whereas 29-nt piRNAs were reduced (36.7% of the control) (Fig. 2B). The extents of the defect in piRNA expression correlated with those in DNA methylation of the Rasgrf1 DMR in the mutants (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 2.

Decreased piRNA levels in piRNA pathway mutants. (A) Size profiles are shown for small RNAs from wild-type (control), Mili−/−, MitoPLD−/−, and Miwi2−/− testes at 16.5 dpc. The peak at 22 nt represents miRNAs, and the other at 24 to 30 nt represents piRNAs. (B) Relative levels of Mili-bound (26-nt) and Miwi2-bound (29-nt) piRNAs compared with wild-type. The levels of miRNA were used to normalize the piRNA levels.

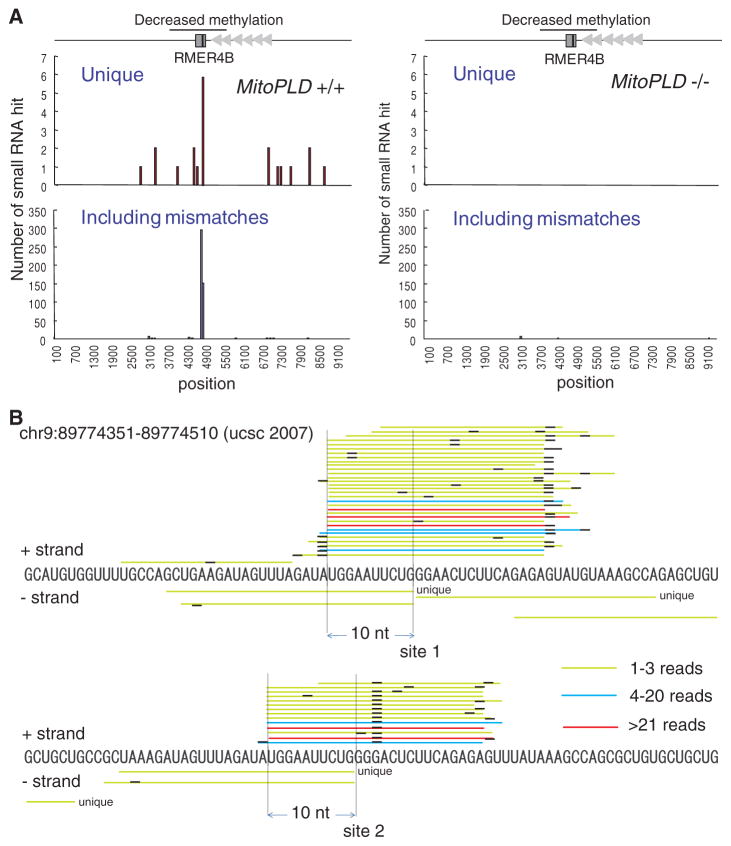

To further explore the link between piRNA and Rasgrf1 methylation, we identified 23- to 31-nt small RNAs mapping to the Rasgrf1 DMR. Twenty-one small RNA reads from wild-type testes uniquely mapped to the DMR with perfect sequence matches (Fig. 3A and table S2), which showed that they are derived from this DMR. In MitoPLD mutants, these small RNAs were lost (Fig. 3A), which indicated that they are indeed piRNAs. When we allowed one or two mismatches, hundreds of piRNAs mapped to a narrow region annotated as an RMER4B sequence, located just upstream of the direct repeat. RMER4B is a solo long terminal repeat (LTR)–type retrotransposon found in a few thousand copies in the mouse genome. Most (95.2%) of these piRNAs also mapped to another RMER4B copy in a piRNA cluster on chr7 with perfect matches (fig. S3 and table S3). Furthermore, most (78.9%) of the chr7-matched piRNAs were unique (table S3), which suggested that they are generated from the chr7 piRNA cluster.

Fig. 3.

An RMER4B sequence in the Rasgrf1 DMR is targeted by piRNAs. (A) Numbers and locations of small RNAs from MitoPLD+/+ (left) and MitoPLD−/− testes (right) at 16.5 dpc mapping to the Rasgrf1 DMR (correspond to mm9 chr9: 89769659–89779158). Results for small RNAs with a unique hit (top) and those with mismatches (up to two mismatches including indels) are shown (bottom). (B) Detailed mapping of piRNAs in the RMER4B copy of the Rasgrf1 DMR. piRNAs are represented by bars colored according to the number of sequence reads obtained. Plus strand hits are shown above the sequence, and minus strand hits are shown below it. Mismatches are represented by black portions of the bars. Unique hit piRNAs are indicated.

The Rasgrf1-derived piRNAs mapped to the minus strand of the Rasgrf1 DMR (Fig. 3B), but the chr7-derived piRNAs predominantly mapped to the plus strand in two small regions (comprising sites 1 and 2 in Fig. 3B), which have similar sequences owing to a sequence duplication. In each mapped region, a 10-nt overlap was observed between the chr7-derived piRNAs and Rasgrf1-derived piRNAs (Fig. 3B), characteristic of the piRNA ping-pong cycle, which generates secondary piRNAs from target RNAs through cleavage by PIWI-piRNAs (21, 22). These observations indicate that an RNA (or RNAs) transcribed from the Rasgrf1 DMR is targeted by the chr7-derived piRNAs.

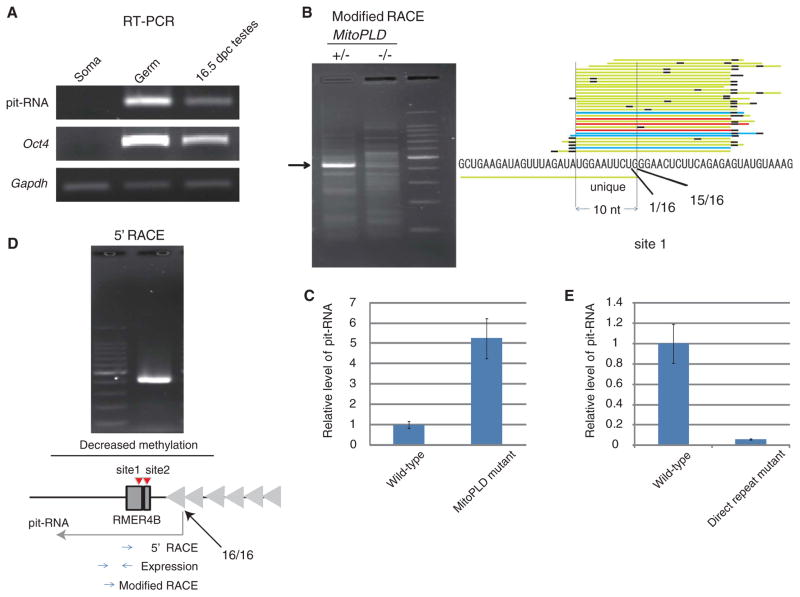

In a region immediately upstream of the RMER4B copy in the Rasgrf1 DMR, we identified an RNA that was specifically expressed in prospermatogonia (Fig. 4A). Cleavage of a target RNA by PIWI-piRNAs creates a 5′ end with monophosphate. To map the cleavage sites in the newly identified RNA, we carried out modified RNA ligase–mediated 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (modified RACE) (23). The most common 5′ end of the RNA fragments mapped precisely to site 1 (Figs. 3B and 4B), which was one of the two ping-pong signature sites. We could not detect fragments cleaved at site 2, probably because of the simultaneous cleavage at site 1, which was proximal to the primer site. The RNA fragments cleaved at site 1 disappeared in MitoPLD mutants, which confirmed that the RNA is targeted by piRNAs. Furthermore, the RNA was up-regulated ~5 times in the mutants (Fig. 4D). We named this RNA “piRNA-targeted noncoding RNA” (pit-RNA). The pit-RNA transcript was specifically expressed during the stage of de novo methylation (SOM text).

Fig. 4.

The Rasgrf1 direct repeat serves as a promoter for pit-RNA. (A) Detection of pit-RNA by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in germ cells from 16.5-dpc testes. Oct4 is a marker for germ cells. (B) Detection of a pit-RNA cleavage site by modified RACE. The numbers of cDNA ends obtained by sequencing the recovered RACE products are also shown (right). (C) Transcription start-site analysis by 5′ RACE. The number of cDNA ends determined by sequencing the RACE products is shown with an arrow in the schematic representation of the region (bottom). The positions of the PCR primers for the analyses are also illustrated. (D) Quantitative PCR analysis of pit-RNA in wild-type and MitoPLD−/− testes at 16.5 dpc. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). The level of Oct4 mRNA was used as a reference. (E) Quantitative PCR analysis of pit-RNA in wild-type and direct repeat mutant testes at 16.5 dpc. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). The level of Oct4 mRNA was used as a reference.

Rasgrf1 is imprinted in mice and rats but not in other rodent species (18). We found that the RMER4B copies are conserved in the rat genome at both the Rasgrf1 DMR and the piRNA cluster. Furthermore, it was reported that the direct repeat essential for the methylation and imprinting of Rasgrf1 (19) is found in mice and rats but not in Peromyscus and rabbits (18). The 5′ end of pit-RNA determined by 5′ RACE indicated that its transcription is initiated within this direct repeat (Fig. 4C). It is therefore possible that the defect in Rasgrf1 imprinting observed in the direct-repeat mutants (19) is a consequence of loss of pit-RNA. Consistent with this notion, pit-RNA was much reduced in testes of the mutants (Fig. 4E). It therefore appears that, through acquisition of the retrotransposon copies and direct repeat, Rasgrf1 acquired imprinting to regulate postnatal growth (24), as explained by the “conflict hypothesis” (25). However, it is also possible that Rasgrf1 imprinting is an inconsequential outcome of the importance of retrotransposon repression in the male germ line (i.e., Rasgrf1 is an innocent bystander), as retrotransposon repression by the piRNA pathway is essential for spermatogenesis.

In the small interfering RNA (siRNA)–mediated transcriptional silencing systems of Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Arabidopsis, polymerase II (Pol II)–transcribed and Pol V–transcribed nascent RNAs, respectively, have been proposed to serve as scaffolds for recruitment of the silencing machinery through siRNA binding (26–28). In the Rasgrf1 locus, the noncoding pit-RNA is targeted by piRNAs, and disruption of pit-RNA transcription results in a failure in de novo methylation. Furthermore, in mice heterozygous for the direct-repeat mutation, only the mutated allele loses methylation (19), which indicates that the repeat acts in cis for methylation. Therefore, although we cannot formally rule out an indirect effect of PIWI-piRNAs, these results together lead us to propose that targeting of nascent pit-RNAs by PIWI-piRNAs at the site of transcription is an important step in the sequence-specific methylation of the Rasgrf1 DMR (fig. S4). In growing oocytes, transcription through the Gnas DMRs is required for their methylation (29), but in this case, involvement of the piRNA pathway is unlikely, because the offspring from Mili, Miwi2, and MitoPLD female mutants show no discernible phenotype (7, 10, 11, 15). In prospermatogonia, however, a large proportion of piRNAs maps to retrotransposons, and it is likely that transcription through retrotransposon sequences has a role in shaping the epigenetic landscape of male germ cells. The methylation patterns established in this way are mostly reprogrammed in early embryos, but the Rasgrf1 DMR is unique in that it maintains the parental origin–specific methylation (SOM text).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Kaneda, S. Chuma, V. Shteyn, and J. Peng for comments on the manuscript and H. Horiike, H. Furuumi, T. Ichiyanagi, Y. Amakawa, H. Chiba, and Y. Li for sample preparation. The accession number for the small RNA sequences is GSE20327. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan to H.S. and K.M.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Bartolomei MS. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2124. doi: 10.1101/gad.1841409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasaki H, Matsui Y. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:129. doi: 10.1038/nrg2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reik W. Nature. 2007;447:425. doi: 10.1038/nature05918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koerner MV, Pauler FM, Huang R, Barlow DP. Development. 2009;136:1771. doi: 10.1242/dev.030403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaefer CB, Ooi SK, Bestor TH, Bourc’his D. Science. 2007;316:398. doi: 10.1126/science.1137544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aravin AA, et al. Mol Cell. 2008;31:785. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, et al. Genes Dev. 2008;22:908. doi: 10.1101/gad.1640708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato Y, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2272. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirasawa R, et al. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1607. doi: 10.1101/gad.1667008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aravin AA, Sachidanandam R, Girard A, Fejes-Toth K, Hannon GJ. Science. 2007;316:744. doi: 10.1126/science.1142612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmell MA, et al. Dev Cell. 2007;12:503. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pane A, Wehr K, Schüpbach T. Dev Cell. 2007;12:851. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malone CD, et al. Cell. 2009;137:522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito K, et al. Nature. 2009;461:1296. doi: 10.1038/nature08501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe T, et al. Dev Cell. 2011;20:364. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 17.de la Puente A, et al. Gene. 2002;291:287. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearsall RS, et al. Genomics. 1999;55:194. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon BJ, et al. Nat Genet. 2002;30:92. doi: 10.1038/ng795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindroth AM, et al. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennecke J, et al. Cell. 2007;128:1089. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunawardane LS, et al. Science. 2007;315:1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1140494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Llave C, Xie Z, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC. Science. 2002;297:2053. doi: 10.1126/science.1076311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drake NM, Park YJ, Shirali AS, Cleland TA, Soloway PD. Mamm Genome. 2009;20:654. doi: 10.1007/s00335-009-9192-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore T, Haig D. Trends Genet. 1991;7:45. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90230-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bühler M, Verdel A, Moazed D. Cell. 2006;125:873. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wierzbicki AT, Ream TS, Haag JR, Pikaard CS. Nat Genet. 2009;41:630. doi: 10.1038/ng.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irvine DV, et al. Science. 2006;313:1134. doi: 10.1126/science.1128813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chotalia M, et al. Genes Dev. 2009;23:105. doi: 10.1101/gad.495809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomizawa S, et al. Development. 2011;138:811. doi: 10.1242/dev.061416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.