Abstract

In recent years, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) has been reported to be a target for the treatment of type II diabetes. Furthermore, it has received attention for its therapeutic potential in many other human diseases, including atherosclerosis, obesity, and cancers. Recent studies have provided evidence that the endogenously produced PPARγ antagonist, 2,3-cyclic phosphatidic acid (cPA), which is similar in structure to lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), inhibits cancer cell invasion and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. We recently observed that cPA negatively regulates PPARγ function by stabilizing the binding of the corepressor protein, silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor. We also showed that cPA prevents neointima formation, adipocyte differentiation, lipid accumulation, and upregulation of PPARγ target gene transcription. We then analyzed the molecular mechanism of cPA's action on PPARγ. In this paper, we summarize the current knowledge on the mechanism of PPARγ-mediated transcriptional activity and transcriptional repression in response to novel lipid-derived ligands, such as cPA.

1. Introduction

Nuclear receptors (NRs) bind to small lipophilic molecules, such as steroids [1] thyroid hormones and active forms of retinoids [2]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) were originally cloned as orphan receptors in 1990 [1, 3]. There are 48 members encoded in the human genome [4]. Subsequently, several clinical studies were performed on clofibrates as ligands for PPARα [5, 6]. PPARα is highly expressed in the liver and is considered the key player in the hepatic fasting response [7, 8]. Clofibrates are a pharmaceutical tool for reducing triglyceride levels and increasing high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol [9]. Other closely related receptors encoded by different genes were subsequently cloned and named PPARδ [10] and PPARγ [11].

PPARγ is a member of the nuclear receptor gene family that plays a central role in the regulation of glucose and lipid homeostasis. Activation of PPARγ by thiazolidinediones (TZDs) leads to altered metabolism in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle cells, and liver, resulting in insulin sensitization [12]. PPARγ agonists also promote adipocytic differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells and stimulate the uptake of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) by macrophages, leading to foam cell formation in the arterial wall [13, 14]. There is considerable evidence supporting a deleterious role for oxidized phospholipids and fatty acids as important signaling molecules in the context of atherosclerotic lesions [15]. Rother et al. reported that lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) antagonists abolish platelet aggregation elicited by mild oxidation of LDL (mox-LDL), indicating that LPA plays an essential role in the thrombogenic effects of mox-LDL [16]. When applied topically to the carotid artery wall in rodents, LPA and the TZD drug rosiglitazone induced PPARγ-mediated intimal thickening [13]. Although their functional roles in the PPARγ transcriptional pathway are not well defined, we recently found that production of cyclic phosphatidic acid (cPA), a simple phospholipid, inhibits transcription of PPARγ target genes that normally drive adipocytic differentiation, lipid accumulation in macrophages, and arterial wall remodeling [14]. We also investigated the structure-activity relationship of activation by naturally occurring lysophospholipids. We found that cPA inhibits PPARγ [14, 17] with high specificity through stabilizing its interaction with the corepressor, silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT) [14]. These results suggest that cPA is partly mediated by the PPARγ signaling pathway. In this paper, we focus on recent advances in the understanding of the interaction of PPARγ with lipid-derived ligands, particularly focusing on the regulation of PPARγ in response to the endogenous lysophosphatidic acid analogs LPA, alkyl-LPA, and cPA.

2. Mechanism of PPARγ-Mediated Effects

2.1. Agonist Regulation of PPARγ

PPARγ is most often implicated in lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity [18, 19]. There are 2 PPARγ isoforms, PPARγ 1 and PPARγ 2. PPARγ 2 has 30 additional amino acids at the N-terminus in humans [20] and is generated from the same gene by mRNA splicing [21]. While PPARγ 1 is expressed with a broad tissue distribution, PPARγ 2 is highly expressed in adipocytes [22], adipose tissue [19], macrophages [23], stomach [24, 25], and colon [26–28]. The role of PPARγ has been extensively studied, and a variety of synthetic and physiological agonists have been identified. Several lines of study have suggested that the binding of different PPARγ ligands can induce a range of distinct PPARγ conformations [29]. PPARγ contains a DNA-binding domain (DBD) that binds to hormone response elements in the promoter of its target genes. Upon agonist binding, PPARγ forms a heterodimer with retinoid X receptors (RXRs). PPARγ activation induces a conformational change in the ligand-dependent activation domain (AF-2 helix) located in the c-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD), which allows coactivator recruitment, corepressor release, and formation of the heterodimeric PPARγ-RXR complex. PPARγ-RXR heterodimer binds the peroxisome proliferator response element (PPRE) in the promoter region of the target genes [30, 31]. The PPARγ-LBD is composed of 13 α-helices and a small 4-stranded β-sheet that forms a ~1440-Å hydrophobic ligand-binding pocket of the nuclear receptor, which binds many different ligands [32]. Together, these findings suggest that these domains are involved not only in ligand recognition but also in protein-protein interactions.

2.2. Synthetic and Natural PPARγ Agonists

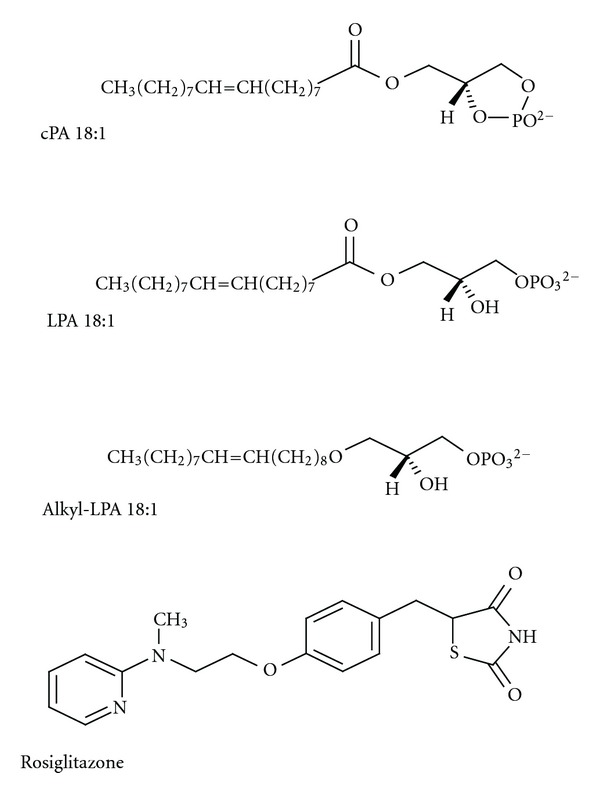

In the last decade, both synthetic and natural PPARγ agonists have been explored for their biological and physiological functions [33]. Synthetic PPARγ agonists, which include rosiglitazone (Avandia) (Figure 1) [34, 35], troglitazone (Rezulin, withdrawn by the FDA due to causing liver failure) [36, 37], and pioglitazone (Actos; Takeda Pharmaceutical Ltd.) [38, 39], have provided insight into the therapeutic potential of PPARγ. These compounds are specific PPARγ ligands with K d s in the 40–500 nM range [34, 40]. They are effective as insulin-sensitizing agents, reducing insulin resistance and lowering plasma glucose levels in patients with type II diabetes (previously known as noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, NIDDM). Recently, these drugs have also been found to be effective in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation [25]. PPARγ activation by its ligands can induce growth arrest, differentiation, and apoptosis of cancer cells. Similarly, PPARγ heterozygous knockout mice have increased susceptibility to chemical carcinogens [41]. Nevertheless, these reports remain controversial and are not well supported. For instance, low concentrations of PPARγ ligands increase cell proliferation, while high concentrations inhibit cell growth in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells [42]. The effective clinical dose of rosiglitazone used in diabetes is 0.11 mg/kg/day [43]. In contrast, the antitumor activity of rosiglitazone in mice requires 100–150 mg/kg/day [43], which is 1,000-fold higher. Therefore, the dosage of PPARγ agonists for cancer therapy must be carefully defined in clinical trials. A recent report suggested that physiological agonists included polyunsaturated acids, such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) [44], linoleic acid [45], and oxidized fatty acid metabolites, cyclopentenone prostaglandin 15-deoxy-Δ12,14 (15d-PGJ2) [46], 8(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (8(S)-HETE) [47], and the lipoxygenase product, 9-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (HODE) [23]. These results were surprising, because these compounds are known to mediate their biological effects through interacting with cell-surface GPCRs, including prostaglandin D2 receptors (DP)1-2 and G protein-coupled receptor 44 (GPR44), prostaglandin E receptors (EP)1-4, prostaglandin F receptor (FP), prostacyclin receptors (IP)1-2, and thromboxane receptors (TP). However, in 1995, Forman et al. first reported that the prostaglandin J2 derivative, 15d-PGJ2, was a natural intracellular agonist of PPARγ as well as a factor of adipocyte determination [46]. 15d-PGJ2 is a product of the cyclooxygenase pathway and is the final metabolite of prostaglandin D2 (PGD2). Some J-series prostaglandins have been found to bind to PPARγ in the low micromolar range [48]. Although 15d-PGJ2 was initially identified as a high-affinity endogenous ligand (K d = 300 nM) [46], the physiological role of 15d-PGJ2 remains unclear. In particular, its concentration in vivo is much lower than that required for its biological functions [49]. Furthermore, apoptosis induced by 15-PGJ2 occurs independently of PPARγ activation and may result from a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [50, 51].

Figure 1.

Structural formulas of LPA, alkyl-LPA, cPA,and rosiglitazone. LPA is made up of a glycerol backbone with a hydroxyl group, a phosphate group, and a long-chain saturated or unsaturated fatty acid. Alkyl-LPA is an alkyl-ether analog of LPA. Alkyl-LPA shows a higher potency than LPA at the intracellular LPA receptor PPARγ. cPA is a naturally occurring acyl analog of LPA. cPA is a weak agonist of plasma membrane LPA receptors, whereas cPA is an inhibitor of PPARγ. Rosiglitazone is a thiazolidinedione (TZD) class of antidiabetics and is full agonist of PPARγ.

2.3. Lipid-Derived PPARγ Agonists

A number of natural ligands for PPARγ have been identified and include 2 main groups of compounds, fatty acids, and phospholipids. More recently, select phospholipids, such as LPA [52], alkyl-glycerophosphate (alkyl-LPA) [53], hexadecyl azelaoyl phosphatidylcholine (azPC) [54], and nitrolinoleic acid and related metabolites [55], have been identified. LPA (Figure 1) has been reported as a bioactive lipid and is derived from hydrolysis of plasma membrane phospholipids [56, 57]. LPA is already wellestablished as a ligand for specific LPA GPCRs belonging to the endothelial cell differentiation gene family [58] and is formed during mox-LDL [13]. Although exogenous LPA can activate PPARγ [52, 59], the reported K d of PPARγ with acyl-LPA(18 : 1) is in the high micromolar range, which is at least an order of magnitude higher than its physiological concentration [52]. Examining the specificity of lipid-derived ligands, such as LPA, for PPARγ is complicated by their poor water solubility and by the need to physically separate PPARγ-bound and -free ligands for measuring the K d. Poor water solubility leads to a high degree of nonspecific binding and reduces physiological significance [60]. However, Davies et al. first reported an oxidatively fragmented alkyl phospholipid in oxidized LDL (oxLDL), termed azPC, as a high-affinity phospholipid-derived ligand of PPARγ [54]. Radiolabeled azPC was shown to bind PPARγ with an affinity of approximately 40 nM, which is equivalent to TZD drugs, like rosiglitazone [54]. Shortly after, our group identified a naturally occurring ether analog of LPA, alkyl-LPA (Figure 1), a high-affinity partial agonist of PPARγ [53]. Alkyl-LPA, but not acyl-LPA, accumulates in mox-LDL and more potently activates PPARγ-mediated transcription compared to acyl-LPA [53]. Binding studies using γ-globulin and polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG) precipitation showed that binding of radiolabeled alky-LPA was concentration dependent and saturable with an apparent K d of 60 nM [53]. To determine the molecular basis of the high-affinity binding to PPARγ, we used molecular modeling techniques to computationally dock alkyl-LPA within the PPARγ pocket residues [53]. Ligand-binding specificity was imposed by the size and charge of the amino acids lining the ligand-binding pocket [61]. Alkyl-LPA hydrocarbons did not form hydrogen bonds with the 2 histidines (His-323 and His-449) as rosiglitazone does [53]. In contrast, the phosphate head group of alkyl-LPA is predicted to make a salt bridge with Arg-288, a residue that is not engaged by rosiglitazone [53]. R288A mutants showed reduced alkyl-LPA binding and reduced transcriptional activity in response to 10 μM alkyl-LPA [53]. The Arg-288 residue likely plays a role in distinguishing the interactions of PPARγ with alky-LPA versus rosiglitazone [53]. These results highlight distinct interactions between alkyl-LPA and rosiglitazone with select residues within the PPARγ-ligand-binding domain.

3. Synthetic and Natural PPARγ Antagonists

As mentioned above, many studies have investigated the roles of PPARγ agonists in many diseases, such as cardiovascular disease in diabetics [62], autoimmune encephalomyelitis [63], lung disease [64], and Alzheimer's disease [65]. However, relatively few reports have described the mechanisms of PPARγ antagonists. Wright et al. reported that bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE), which is a compound used in the manufacture of industrial plastics, is a synthetic antagonist of PPARγ with a K d of 100 μM [66]. BADGE can antagonize rosiglitazone's activation of PPARγ transcriptional activity and adipogenic action in 3T3-L1 and 3T3-F442A preadipocyte cells. BADGE also affected the expression of different adipocyte-specific markers, including adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein (aP2), glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPD), glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4), and adipsin. However, Bishop-Bailey et al. reported that BADGE is a PPARγ agonist in a human urinary bladder carcinoma cell line, ECV304, that stably expresses the rat acyl-CoA PPAR response element (PPRE) linked to drive the expression of luciferase [67]. Furthermore, Nakamura et al. reported that BADGE is a PPARγ agonist in the macrophage-like cell line, RAW 264.7, and suppressed tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) production [68]. These reports suggest that the regulation of PPARγ activation or inhibition may have greater cell-type specificity than previously thought. Rieusset et al. reported that dimethyl α-(dimethoxyphosphinyl)-p-chlorobenzyl phosphate (SR-202) is a selective synthetic PPARγ antagonist that blocks adipocyte differentiation induced by troglitazone [69]. SR-202 attenuates agonist-induced PPARγ transcriptional activity (IC50 = 140 μM) and improves insulin sensitivity in diabetic ob/ob mice. It also increases HDL levels in rats, indicating its potential for treating obesity and type II diabetes. PD068235, a reported PPARγ antagonist, inhibited rosiglitazone-dependent PPARγ transcriptional activity with an IC50 of 0.84 μM and prevented association with the agonist-induced coactivator, SRC-1 [70]. PD068235 itself did not significantly change PPARγ transcriptional activity; however, cotreatment with rosiglitazone dose dependently decreased PPARγ transcriptional activity.

2-chloro-5-nitrobenzanilide (GW9662) is a potent, irreversible, and selective PPARγ antagonist (IC50 = 3.3 nM) in both cell-free and cell-based assays, which acts by covalently modifying a cysteine residue (Cys 286) in the PPARγ-LBD [71]. Interestingly, GW9662 enhanced the inhibitory effect of the agonist rosiglitazone on breast cancer cells rather than rescuing tumor growth, suggesting that PPARγ activation may not be involved in inhibition of survival and cell growth caused by agonists [72]. In 2002, a very potent and selective non-TZD-derived PPARγ antagonist, 2-chloro-5-nitro-N-4-pyridinylbenza (T0070907), was newly identified [73]. It was reported to bind PPARγ with a high affinity (IC50 = 1 nM) and block adipocyte differentiation. Furthermore, T0070907 promoted the recruitment of the transcriptional corepressor NCoR [74] as a result of binding to PPARγ and causing conformational changes. In contrast, very few endogenous PPARγ antagonists have been described. Prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) was first described as naturally occurring PPARγ antagonist; it potently inhibits adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells [75]. A main step in the synthesis of PGF2α is the conversion of arachidonic acid into the unstable intermediate prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) through the activity of cyclooxygenase (COX) [76]. PGF2α induces MAP kinase activation, leading to the phosphorylation of PPARγ at Ser 112. This effect suggests that PGF2α indirectly antagonized PPARγ induction and inhibited adipocyte differentiation [75]. Our recent work identified cPA (Figure 1) as a naturally occurring PPARγ antagonist generated by phospholipase D2 (PLD2). cPA is an analog of LPA with a 5-atom ring linking the phosphate to 2 of the glycerol carbons. cPA is found in diverse organisms, from slime mold to humans [77, 78]; however, its functions are largely unknown. The concentration of cPA in human serum is estimated to be ~10 nM, which is ~100-fold lower than that of LPA. Although cPA is structurally similar to LPA, it has several unique actions. cPA inhibits cell proliferation, induces actin stress fiber formation, promotes differentiation and survival of cultured embryonic hippocampal neurons, inhibits LPA-induced platelet aggregation, and suppresses cancer cell invasion and metastasis in vitro and in vivo [79–81].

4. Transcriptional Corepressors and Epigenetic Modifications

4.1. PPARγ Ligands and Epigenetic Control

We showed that cPA negatively regulates PPARγ functions by stabilizing the SMRT-PPARγ complex [14]. Epigenetic mechanisms are often responsible for regulating specific gene activation and repression [82]. DNA methylation and histone modification serve as epigenetic markers for active or inactive chromatin. Gene repression through posttranslational modification is targeted to specific DNA sites through DNA methylation [83]. Epigenesis plays a vital role in the regulation of gene expression; DNA methylation plays an important role in these structural changes [84]. DNA methylation occurs on cytosine bases and is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases.

In general, DNA methylation is thought to repress gene transcription through either directly preventing the binding of transcription factors or by creating binding sites for methyl-binding proteins [85]. Several studies have reported that epigenetic regulatory mechanisms are involved in the transcriptional activation of PPARγ in 3T3-L1 adipocytes [86]. Fujiki et al. recently reported that the PPARγ gene is regulated by DNA methylation of its promoter region, which reduces expression of PPARγ [87]. These findings suggest that DNA methylation of the PPARγ promoter contributes to its expression during adipocyte differentiation.

Acetylation of core histone proteins occurs on specific lysine residues, creating a neutral charge that loosens DNA-histone interactions and permits the binding of transcription factors [88]. Many proteins have been identified as coregulators that can be recruited by nuclear receptors to affect transcriptional regulation. The corepressor for PPARγ is a protein complex containing histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) and SMRT or NCoR. A number of PPARγ interacting partners have been identified, many of which are known epigenetic regulators, including HDAC3 [89, 90]. HDACs repress gene expression by deacetylating histones and condensing chromatin. Many nuclear receptors, including PPARγ in the unligated or antagonist-bound state, repress transcription by recruiting corepressors [91, 92], which bind to the heterodimer to suppress target gene activation. The nuclear receptor corepressor NCoR and SMRT are structurally related and extensively studied corepressors. NCoR and SMRT are encoded by separate loci but share a similar modular structure. The N-terminus contains several repression domains (RDs). The PPARγ AF2 domain is accessible and can interact with the extended LXXXIXXXL consensus motif of NR corepressors [93]. These corepressor complexes significantly regulate the control of transcription in inactive states [8]. NCoR and SMRT nucleate a core corepressor complex that contains HDAC3, transducin β-like 1 (TBL1), TBL1-related protein (TBLR1), and G protein pathway suppressor 2 (GPS2), forming a functional holocomplex [94]. HDAC3 is found in a tight complex with SMRT and NCoR in diverse repression pathways [95]. These 2 corepressors recruit HDAC3 to specific promoters, where it deacetylates histones and mediates silencing of the corresponding genes. TBL1 is a 6 WD-40 repeat-containing protein (also known as beta-transducin repeat) that was identified as a subunit of the SMRT complex [96]. Both TBL1 and TBLR1 interact directly with SMRT and NCoR but not with HDAC3. They activate PPARγ-dependent transcription in response to rosiglitazone. The transcriptional activity of PPARγ is controlled by DNA-binding activity and nuclear receptor cofactors [97]. These corepressor complexes associate with a variety of factors that mediate transcription repression.

4.2. cPA-Induced Corepressor SMRT and Interaction with Human Diseases

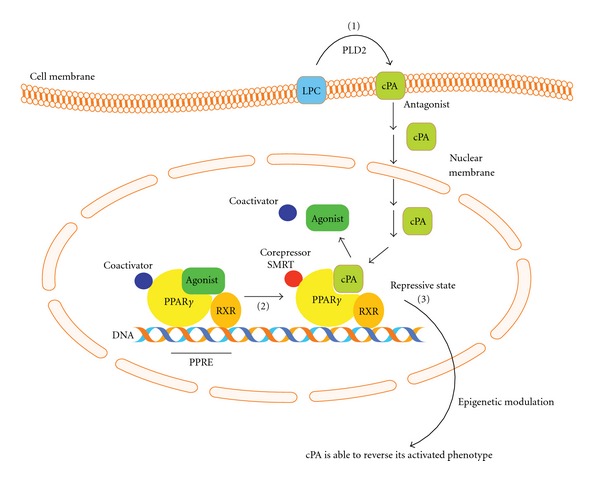

Our recent report used a corepressor 2-hybrid assay to show that cPA negatively regulates PPARγ function by stabilizing the SMRT-PPARγ complex (Figure 2) and blocks rosiglitazone-stimulated adipogenesis and lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 and RAW246.7 macrophage-like cells [14]. This ligand-dependent corepressor exchange results in transcriptional repression of genes involved in the control of insulin action as well as a diverse range of other functions [98]. We also demonstrated that activation of PLD2-mediated cPA production by insulin or topical application of cPA together with PPARγ agonists prevents neointima formation, adipocytic differentiation, lipid accumulation, and upregulation of PPARγ target genes [13, 14]. Atherosclerosis is the leading cause of death among cardiovascular diseases. Neointima formation is a common feature of an atherosclerotic artery and is characterized by smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition in the vascular intimal layer. Yoshida et al. first reported that LPA and species containing unsaturated LPA (16 : 1, 18 : 1 and 18 : 2) induced neointima formation when injected into the rat carotid artery [99]. Furthermore, LPA and alkyl-LPA induced neointima formation through the activation of PPARγ, whereas cPA inhibited PPARγ-mediated arterial wall remodeling in a noninjury infusion model [13, 14]. These results suggest that PPARγ is required for LPA-induced neointima formation. PPARγ antagonists should continue to be developed, as they have the clinical potential for preventing neointimal vascular lesions.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the PPARγ signaling. cPA is generated intracellularly in a stimulus-coupled manner by the PLD2 enzyme (1). cPA inhibits PPARγ activation and stabilizes binding of PPARγ corepressor SMRT (2). Agonists (LPA, alkyl-LPA, and rosiglitazone) activate PPARγ and promote downstream signals, whereas cPA negatively regulates PPARγ. cPA stabilizes PPARγ-SMRT corepressor complex and inhibits PPARγ-mediated postsignal transduction (3).

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we have focused on recent developments elucidating the role of lysophospholipids in intracellular signaling and PPARγ activation and inhibition. Our proposed mechanism of action for the cPA-PPARγ axis is summarized in Figure 2. Lysophospholipids fulfill dual role as mediators, through the activation of cell surface GPCRs, and as intracellular second messengers, through the activation and inhibition of PPARγ. PPARγ-corepressor interactions are physiologically relevant, as reports have demonstrated the involvement of chromatin-modifying cofactors in diseases, such as cancer [100] and metabolic syndrome diseases [101]. However, the physiological context of these compounds in PPARγ signaling is still unclear. Further clarification of the PPARγ-cPA axis could allow the synthesis of novel medicines that modulate PPARγ.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders (to T. Tsukahara), Takeda Science Foundation (to T. Tsukahara) and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) 22591482 (to T. Tsukahara) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

References

- 1.Issemann I, Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature. 1990;347(6294):645–650. doi: 10.1038/347645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renaud JP, Moras D. Structural studies on nuclear receptors. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2000;57(12):1748–1769. doi: 10.1007/PL00000656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreyer C, Krey G, Keller H, Givel F, Helftenbein G, Wahli W. Control of the peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway by a novel family of nuclear hormone receptors. Cell. 1992;68(5):879–887. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson-Rechavi M, Carpentier AS, Duffraisse M, Laudet V. How many nuclear hormone receptors are there in the human genome? Trends in Genetics. 2001;17(10):554–556. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gulick T, Cresci S, Caira T, Moore DD, Kelly DP. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor regulates mitochondrial fatty acid oxidative enzyme gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(23):11012–11016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kersten S, Seydoux J, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α mediates the adaptive response to fasting. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103(11):1489–1498. doi: 10.1172/JCI6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer CN, Hsu MH, Griffin KJ, Raucy JL, Johnson EF. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-α expression in human liver. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;53(1):14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reilly SM, Bhargava P, Liu S, et al. Nuclear receptor corepressor SMRT regulates mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and mediates aging-related metabolic deterioration. Cell Metabolism. 2010;12(6):643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferré P. The biology of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: relationship with Lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2004;53(Supplement 1):S43–S50. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krey G, Keller H, Mahfoudi A, et al. Xenopus peroxisome proliferator activated receptors: genomic organization, response element recognition, heterodimer formation with retinoid x receptor and activation by fatty acids. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1993;47(1–6):65–73. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elbrecht A, Chen Y, Cullinan CA, et al. Molecular cloning, expression and characterization of human peroxisome proliferator activated receptors γ1 and γ2. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1996;224(2):431–437. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Way JM, Harrington WW, Brown KK, et al. Comprehensive messenger ribonucleic acid profiling reveals that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activation has coordinate effects on gene expression in multiple insulin-sensitive tissues. Endocrinology. 2001;142(3):1269–1277. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.3.8037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang C, Baker DL, Yasuda S, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid induces neointima formation through PPARγ activation. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;199(6):763–774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsukahara T, Tsukahara R, Fujiwara Y, et al. Phospholipase D2-dependent inhibition of the nuclear hormone receptor PPARγ by cyclic phosphatidic acid. Molecular Cell. 2010;39(3):421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng F, Cornacchia F, Schulman I, et al. Development of albuminuria and glomerular lesions in normoglycemic B6 recipients of db/db mice bone marrow: the role of mesangial cell progenitors. Diabetes. 2004;53(9):2420–2427. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rother E, Brandl R, Baker DL, et al. Subtype-selective antagonists of lysophosphatidic acid receptors inhibit platelet activation triggered by the lipid core of atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 2003;108(6):741–747. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000083715.37658.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oishi-Tanaka Y, Glass CK. A new role for cyclic phosphatidic acid as a PPARγ antagonist. Cell Metabolism. 2010;12(3):207–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma AM, Staels B. Review: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and adipose tissue—Understanding obesity-related changes in regulation of lipid and glucose metabolism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92(2):386–395. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitehead JP. Diabetes: new conductors for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) orchestra. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2011;43(8):1071–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPARγ2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell. 1994;79(7):1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fajas L, Auboeuf D, Raspé E, et al. The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARγ gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(30):18779–18789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacDougald OA, Lane MD. Transcriptional regulation of gene expression during adipocyte differentiation. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1995;64:345–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagy L, Tontonoz P, Alvarez JG, Chen H, Evans RM. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARγ . Cell. 1998;93(2):229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huin C, Corriveau L, Bianchi A, et al. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in the developing human fetal digestive tract. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2000;48(5):603–611. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheon CW, Kim DH, Kim DH, Cho YH, Kim JH. Effects of ciglitazone and troglitazone on the proliferation of human stomach cancer cells. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;15(3):310–320. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarraf P, Mueller E, Jones D, et al. Differentiation and reversal of malignant changes in colon cancer through PPARγ . Nature Medicine. 1998;4(9):1046–1052. doi: 10.1038/2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saez E, Tontonoz P, Nelson MC, et al. Activators of the nuclear receptor PPARγ enhance colon polyp formation. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(9):1058–1061. doi: 10.1038/2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai Y, Wang WH. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and colorectal cancer. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 2010;2(3):159–164. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i3.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camp HS, Li O, Wise SC, et al. Differential activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ by troglitazone and rosiglitazone. Diabetes. 2000;49(4):539–547. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, et al. The nuclear receptor super-family: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83(6):835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brivanlou AH, Darnell JE., Jr. Signal transduction and the control of gene expression. Science. 2002;295(5556):813–818. doi: 10.1126/science.1066355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nolte RT, Wisely GB, Westin S, et al. Ligand binding and co-activator assembly of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ . Nature. 1998;395(6698):137–143. doi: 10.1038/25931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schupp M, Lazar MA. Endogenous ligands for nuclear receptors: digging deeper. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(52):40409–40415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.182451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Wilkison WO, Willson TM, Kliewer SA. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(22):12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldstein BJ. Rosiglitazone. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2000;54(5):333–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lenhard JM, Kliewer SA, Paulik MA, Plunket KD, Lehmann JM, Weiel JE. Effects of troglitazone and metformin on glucose and lipid metabolism. Alterations of two distinct molecular pathways. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1997;54(7):801–808. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang M, Wise SC, Leff T, Su TZ. Troglitazone, an antidiabetic agent, inhibits cholesterol biosynthesis through a mechanism independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ . Diabetes. 1999;48(2):254–260. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawrence JM, Reckless J. Pioglitazone. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2000;54(9):614–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillies PS, Dunn CJ. Pioglitazone. Drugs. 2000;60(2):333–343. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park SW, Yi JH, Miranpuri G, et al. Thiazolidinedione class of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists prevents neuronal damage, motor dysfunction, myelin loss, neuropathic pain, and inflammation after spinal cord injury in adult rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2007;320(3):1002–1012. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.113472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peraza MA, Burdick AD, Marin HE, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. The toxicology of ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) Toxicological Sciences. 2006;90(2):269–295. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clay CE, Namen AM, Atsumi GI, et al. Magnitude of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activation is associated with important and seemingly opposite biological responses in breast cancer cells. Journal of Investigative Medicine. 2001;49(5):413–420. doi: 10.2310/6650.2001.33786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panigrahy D, Huang S, Kieran MW, Kaipainen A. PPARγ as a therapeutic target for tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Biology and Therapy. 2005;4(7):687–693. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.7.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allred CD, Talbert DR, Southard RC, Wang X, Kilgore MW. PPARγ1 as a molecular target of eicosapentaenoic acid in human colon cancer (HT-29) cells. Journal of Nutrition. 2008;138(2):250–256. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Capobianco E, White V, Higa R, Martínez N, Jawerbaum A. Effects of natural ligands of PPARγ on lipid metabolism in placental tissues from healthy and diabetic rats. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2008;14(8):491–499. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gan039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun RP, Spiegelman BM, Evans RM. 15-deoxy-Δ12, 14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPARγ . Cell. 1995;83(5):803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu K, Bayona W, Kallen CB, et al. Differential activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors by eicosanoids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(41):23975–23983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kliewer SA, Lenhard JM, Willson TM, Patel I, Morris DC, Lehmann JM. A prostaglandin J2 metabolite binds peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and promotes adipocyte differentiation. Cell. 1995;83(5):813–819. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobayashi Y, Ueki S, Mahemuti G, et al. Physiological levels of 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 prime eotaxin-induced chemotaxis on human eosinophils through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ ligation. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175(9):5744–5750. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim EH, Na HK, Kim DH, et al. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 induces COX-2 expression through Akt-driven AP-1 activation in human breast cancer cells: a potential role of ROS. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(4):688–695. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee SJ, Kim MS, Park JY, Woo JS, Kim YK. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 induces apoptosis via JNK-mediated mitochondrial pathway in osteoblastic cells. Toxicology. 2008;248(2-3):121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McIntyre TM, Pontsler AV, Silva AR, et al. Identification of an intracellular receptor for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA): LPA is a transcellular PPARγ agonist. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(1):131–136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135855100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsukahara T, Tsukahara R, Yasuda S, et al. Different residues mediate recognition of 1-O-oleyl-lysophosphatidic acid and rosiglitazone in the ligand binding domain of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ . Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(6):3398–3407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510843200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davies SS, Pontsler AV, Marathe GK, et al. Oxidized alkyl phospholipids are specific, high affinity peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands and agonists. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(19):16015–16023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y, Zhang J, Schopfer FJ, et al. Molecular recognition of nitrated fatty acids by PPARγ . Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2008;15(8):865–867. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moolenaar WH, Jalink K, van Corven EJ. Lysophosphatidic acid: a bioactive phospholipid with growth factor-like properties. Reviews of Physiology Biochemistry and Pharmacology. 1992;119:47–65. doi: 10.1007/3540551921_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tigyi G, Dyer DL, Miledi R. Lysophosphatidic acid possesses dual action in cell proliferation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(5):1908–1912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tigyi G, Parrill AL. Molecular mechanisms of lysophosphatidic acid action. Progress in Lipid Research. 2003;42(6):498–526. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stapleton CM, Mashek DG, Wang S, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid activates peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ in CHO cells that over-express glycerol 3-phosphate acyltransferase-1. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018932. Article ID e18932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mendel CM, Mendel DB. “Non-specific” binding. The problem, and a solution. Biochemical Journal. 1985;228(1):269–272. doi: 10.1042/bj2280269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu HE, Lambert MH, Montana VG, et al. Structural determinants of ligand binding selectivity between the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(24):13919–13924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241410198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Staels B, Fruchart JC. Therapeutic roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists. Diabetes. 2005;54(8):2460–2470. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Racke MK, Gocke AR, Muir M, Diab A, Drew PD, Lovett-Racke AE. Nuclear receptors and autoimmune disease: the potential of PPAR agonists to treat multiple sclerosis. Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136(3):700–703. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.3.700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Belvisi MG, Hele DJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors as novel targets in lung disease. Chest. 2008;134(1):152–157. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sato T, Hanyu H, Hirao K, Kanetaka H, Sakurai H, Iwamoto T. Efficacy of PPAR-γ agonist pioglitazone in mild Alzheimer disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2011;32(9):1626–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wright HM, Clish CB, Mikami T, et al. A synthetic antagonist for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ inhibits adipocyte differentiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(3):1873–1877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bishop-Bailey D, Hla T, Warner TD. Bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE) is a PPARγ agonist in an ECV304 cell line. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;131(4):651–654. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakamuta M, Enjoji M, Uchimura K, et al. Bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE) suppresses tumor necrosis factor-α production as a PPARγ agonist in the murine macrophage-like cell line, RAW 264.7. Cell Biology International. 2002;26(3):235–241. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2001.0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rieusset J, Touri F, Michalik L, et al. A new selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ antagonist with antiobesity and antidiabetic activity. Molecular Endocrinology. 2002;16(11):2628–2644. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Camp HS, Chaudhry A, Leff T. A novel potent antagonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ blocks adipocyte differentiation but does not revert the phenotype of terminally differentiated adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2001;142(7):3207–3213. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leesnitzer LM, Parks DJ, Bledsoe RK, et al. Functional consequences of cysteine modification in the ligand binding sites of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors by GW9662. Biochemistry. 2002;41(21):6640–6650. doi: 10.1021/bi0159581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Al-Alem L, Southard RC, Kilgore MW, Curry TE. Specific thiazolidinediones inhibit ovarian cancer cell line proliferation and cause cell cycle arrest in a PPARγ independent manner. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016179. Article ID e16179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee G, Elwood F, McNally J, et al. T0070907, a selective ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, functions as an antagonist of biochemical and cellular activities. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(22):19649–19657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Horlein AJ, Naar AM, Heinzel T, et al. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature. 1995;377(6548):397–404. doi: 10.1038/377397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reginato MJ, Krakow SL, Bailey ST, Lazar MA. Prostaglandins promote and block adipogenesis through opposing effects on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ . Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(4):1855–1858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vane SJ. Differential inhibition of cyclooxygenase isoforms: an explanation of the action of NSAIDs. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 1998;4(supplement 5):S3–S10. doi: 10.1097/00124743-199810001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Murakami-Murofushi K, Mukai M, Kobayashi S, Kobayashi T, Tigyi G, Murofushi H. A novel lipid mediator, cyclic phosphatidic acid (cPA), and its biological functions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2000;905:319–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fujiwara Y. Cyclic phosphatidic acid—a unique bioactive phospholipid. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2008;1781(9):519–524. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Murakami-Murofushi K, Uchiyama A, Fujiwara Y, et al. Biological functions of a novel lipid mediator, cyclic phosphatidic acid. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2002;1582(1–3):1–7. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bakera DL, Fujiwara Y, Pigg KR, et al. Carba analogs of cyclic phosphatidic acid are selective inhibitors of autotaxin and cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(32):22786–22793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512486200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Uchiyama A, Mukai M, Fujiwara Y, et al. Inhibition of transcellular tumor cell migration and metastasis by novel carba-derivatives of cyclic phosphatidic acid. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1771(1):103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sugii S, Evans RM. Epigenetic codes of PPARγ in metabolic disease. FEBS Letters. 2011;585(13):2121–2128. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8(4):286–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hamilton JP. Epigenetics: principles and practice. Digestive Diseases. 2011;29(2):130–135. doi: 10.1159/000323874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bird AP, Wolffe AP. Methylation-induced repression-belts, braces, and chromatin. Cell. 1999;99(5):451–454. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Musri MM, Gomis R, Párrizas M. Chromatin and chromatin-modifying proteins in adipogenesis. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2007;85(4):397–410. doi: 10.1139/O07-068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fujiki K, Kano F, Shiota K, Murata M. Expression of the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ gene is repressed by DNA methylation in visceral adipose tissue of mouse models of diabetes. BMC Biology. 2009;7, article 38 doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Green CD, Han JDJ. Epigenetic regulation by nuclear receptors. Epigenomics. 2011;3(1):59–72. doi: 10.2217/epi.10.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Grunstein M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature. 1997;389(6649):349–352. doi: 10.1038/38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang J, Henagan TM, Gao Z, Ye J. Inhibition of glyceroneogenesis by histone deacetylase 3 contributes to lipodystrophy in mice with adipose tissue inflammation. Endocrinology. 2011;152(5):1829–1838. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hermanson O, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Nuclear receptor coregulators: multiple modes of modification. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;13(2):55–60. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Baniahmad A. Nuclear hormone receptor co-repressors. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2005;93(2–5):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Heldring N, Pawson T, McDonnell D, Treuter E, Gustafsson JÅ, Pike AC. Structural insights into corepressor recognition by antagonist-bound estrogen receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(14):10449–10455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611424200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rosenfeld MG, Lunyak VV, Glass CK. Sensors and signals: a coactivator/corepressor/epigenetic code for integrating signal-dependent programs of transcriptional response. Genes and Development. 2006;20(11):1405–1428. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Karagianni P, Wong J. HDAC3: taking the SMRT-N-CoRrect road to repression. Oncogene. 2007;26(37):5439–5449. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li J, Wang J, Wang J, et al. Both corepressor proteins SMRT and N-CoR exist in large protein complexes containing HDAC3. EMBO Journal. 2000;19(16):4342–4350. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Perissi V, Rosenfeld MG. Controlling nuclear receptors: the circular logic of cofactor cycles. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2005;6(7):542–554. doi: 10.1038/nrm1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Aranda A, Pascual A. Nuclear hormone receptors and gene expression. Physiological Reviews. 2001;81(3):1269–1304. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yoshida K, Nishida W, Hayashi K, et al. Vascular remodeling induced by naturally occurring unsaturated lysophosphatidic acid in vivo . Circulation. 2003;108(14):1746–1752. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000089374.35455.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tsukahara T, Hanazawa S, Kobayashi T, Iwamoto Y, Murakami-Murofushi K. Cyclic phosphatidic acid decreases proliferation and survival of colon cancer cells by inhibiting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ . Prostaglandins and Other Lipid Mediators. 2010;93(3-4):126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tsukahara T, Hanazawa S, Murakami-Murofushi K. Cyclic phosphatidic acid influences the expression and regulation of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 3B and lipolysis in 3T3-L1 cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2011;404(1):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]