Abstract

Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common soft-tissue sarcoma in children. While cytogenetic abnormalities have been well characterized in this disease, aberrant epigenetic events such as DNA hypermethylation have not been described in genome-wide studies. We have analyzed the methylation status of 25,500 promoters in normal skeletal muscle, and in cell lines and tumor samples of embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma from pediatric patients. We identified over 1,900 CpG islands that are hypermethylated in rhabdomyosarcomas relative to skeletal muscle. Genes involved in tissue development, differentiation, and oncogenesis such as DNAJA4, HES5, IRX1, BMP8A, GATA4, GATA6, ALX3, and P4HTM were hypermethylated in both RMS cell lines and primary samples, implicating aberrant DNA methylation in the pathogenesis of rhabdomyosarcoma. Furthermore, cluster analysis revealed embryonal and alveolar subtypes had distinct DNA methylation patterns, with the alveolar subtype being enriched in DNA hypermethylation of polycomb target genes. These results suggest that DNA methylation signatures may aid in the diagnosis and risk stratification of pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma and help identify new targets for therapy.

Keywords: DNA Methylation, epigenetics, Polycomb, rhabdomyosarcoma

Introduction

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is the most common soft-tissue sarcoma in children. Approximately 350 new cases are diagnosed in the US each year, accounting for about 5% of childhood cancers.1 Rhabdomyosarcomas are thought to be of skeletal muscle origin and are divided into three main subtypes based on both histology and chromosomal characterization.2 Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas (aRMS) are more aggressive, occur more commonly in young adults, and are found in the trunk and extremities. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas (eRMS) occur most frequently in children under 10 y old and are found in the head, neck, genitourinary tract, and retroperitoneum. The third, less common, subtype, pleomorphic, has a much less distinct histological pattern intermediate between eRMS and aRMS and usually occurs in adults.

The two major subtypes of RMS are associated with characteristic cytogenetic abnormalities that could contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease. Eighty percent of aRMS are characterized by either a t(2; 13) or t(1; 13) translocation resulting in expressed PAX3:FOXO1 or PAX7:FOXO1 fusions.2 PAX3 and PAX7 are paired box transcription factors that are important in early muscle development but can suppress myogenic differentiation. FOXO1 is a member of the forkhead transcription factor family. There is evidence to suggest that the PAX3:FOXO1 fusion is associated with more aggressive cancers than the PAX7:FOXO1 fusion.3 The remaining 20% of fusion-negative aRMS are difficult to differentiate from eRMS. eRMS and other pediatric cancers such as Wilms tumor commonly exhibit loss of heterozygosity at 11p15,4 suggesting that this region contains a tumor suppressor. Recently, a putative tumor suppressor gene (HOTS) was identified at the H19 locus on 11p15 that can inhibit Wilms and rhabdomyosarcoma tumor cell growth.5

Cytosine methylation plays a role in both normal tissue development and cancer.6 The role of aberrant DNA methylation in the development of cancer has been well studied in adult malignancies. The genome of cancer cells is generally hypomethylated compared with normal tissue.7 This hypomethylation is primarily due to the loss of methylation at repetitive elements of the genome. While the total amount of methylated DNA in cancer cells in less than normal cells, CpG islands in the 5′ regulatory regions of genes are often hypermethylated in tumors and are thought to be important for the origin of many cancers. Hypermethylation of CpG islands can lead to transcriptional repression, and the finding that tumor suppressor genes can be silenced by this mechanism has led to the hypothesis that aberrant DNA methylation may be an early step in the process of carcinogenesis.

There have been relatively few studies of DNA methylation in pediatric cancers. Aberrant DNA methylation events have been reported in RMS, but no genome-wide DNA methylation experiments have been described. Previous studies have used a candidate gene approach to identify methylation changes in RMS samples at the FGFR1,8 JUP,9 MYOD1,10 PAX3,11 and RASSF112 promoters. DNA methylation changes likely play a role in the pathogenesis of rhabdomyosarcoma as demonstrated by the observation that the treatment of the RMS cell line RMZ-RC2 with the DNA demethylating agent 5-azacytidine results in differentiation.13 This differentiation indicates that aberrant DNA methylation is repressing the expression of a gene(s) required for differentiation in this cell line.

To examine how aberrant DNA methylation might contribute to pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma, we conducted a genome-wide analysis of promoter CpG island methylation between rhabdomyosarcoma subtypes and skeletal muscle. We detect RMS-specific aberrant DNA methylation in genes associated with tissue development, differentiation, and oncogenesis. Hierarchical cluster analysis reveals that genome-wide DNA methylation patterns can distinguish RMS subtypes, with polycomb target genes being strongly enriched in alveolar RMS. These results suggest that aberrant DNA methylation epigenetically silences genes important for the pathogenesis of pediatric RMS, and DNA methylation signatures have the potential to distinguish RMS subtypes for treatment planning.

Results

Denaturation Analysis of Methylation Differences (DAMD) identifies cancer-specific methylation signatures in RMS cell lines

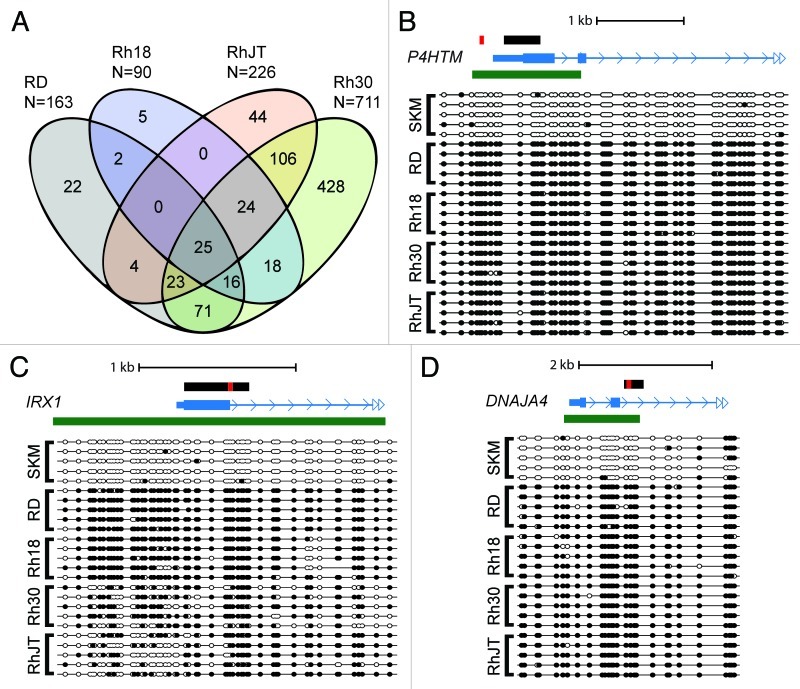

The Denaturation Analysis of Methylation Differences (DAMD) assay enriches for DNA methylation differences in GC-rich regions of the genome such as CpG islands based on the increased melting temperature of cytosine methylated DNA. This assay was used previously to detect aberrant DNA methylation in pediatric medulloblastomas.14 We initially performed the DAMD assay to identify DNA hypermethylated regions of the genome in four human RMS cell lines relative to skeletal muscle. The cell lines RhJT and Rh30 are derived from alveolar RMS, while RD and Rh18 are characterized as embryonal. Because we were interested in identifying differential methylation in promoter regions of the genome, we used the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Promoter 1.0R Array consisting of ~25,500 promoter regions with an average coverage from -7.5 to +2.45 kb relative to the transcriptional start site. We obtained positive signals (RMS cell line > skeletal muscle; log2(signal ratio) > 1.2 and p < 0.001) in the promoter regions of 90 loci for Rh18, 163 loci for RD, 226 loci for RhJT, and 711 for Rh30. Many of these loci were shared between the different cell lines (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Common hypermethylated loci are identified in rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) cell lines. (A) DAMD-positive loci are depicted from four human RMS cell lines (RD, Rh18, RhJT, and Rh30). Normal skeletal muscle was used a control. The total number of DAMD-positive loci for each sample is shown, and common loci between the four cell lines are depicted on the Venn diagram. (B-D) Bisulfite sequence analysis of P4HTM, IRX1, and DNAJA4 from the RMS cell lines and normal skeletal muscle (SKM). The black rectangle shows the genomic region subjected to bisulfite sequence analysis; the red rectangle shows the region analyzed using quantitative Pyrosequencing in Figure 2B; the mRNA structure (exon, large rectangle; intron, thin line; UTR, small rectangle; arrow, direction of transcription) is shown in blue; and any associated CpG island is shown using a green rectangle. Solid circles represent CpG methylation, and open circles depict unmodified CpG dinucleotides.

To confirm that the DAMD-positive loci corresponded to areas of DNA hypermethylation, we subjected loci common to all four RMS cell lines (P4HTM, IRX1, and DNAJA4) to bisulfite sequence analysis. Shared DAMD-positive genomic regions were located in large CpG islands and were all heavily methylated in the RMS cell lines and unmethylated in normal skeletal muscle (Fig. 1B–D).

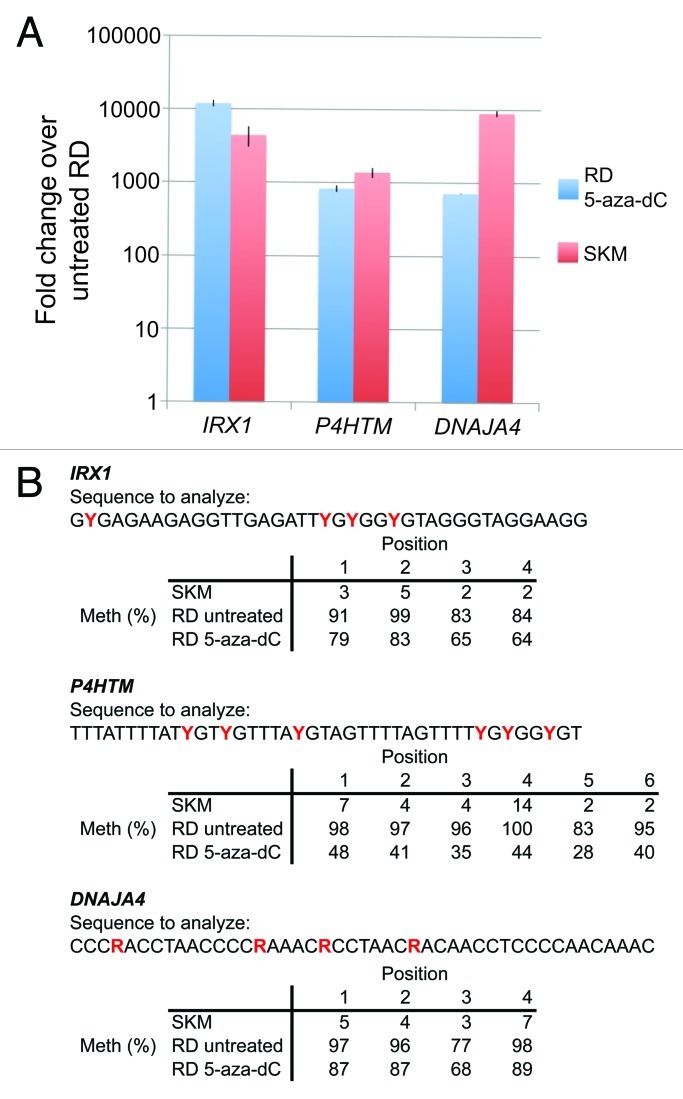

Promoter methylation in cancer cells is often associated with gene silencing. To determine whether the DNA hypermethylation observed suppresses mRNA expression, we performed RT-qPCR analysis for IRX1, P4HTM, and DNAJA4 from RD cells treated with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC), as well as RNA obtained from untreated RD cells, and normal adult skeletal muscle. When compared with untreated RD cells, treatment with 5-aza-dC induced transcription ~1000–10000-fold for the three transcripts, consistent with the hypothesis that promoter CpG island DNA hypermethylation epigenetically silences these loci in RD cells (Fig. 2A). The mRNA transcript levels of these genes were also detected to a similar level in normal adult skeletal muscle, suggesting that these genes play a role in normal muscle cell biology. To confirm that 5-aza-dC treatment of RD cells affected the methylation status of the promoter CpG islands, we performed quantitative bisulfite sequence analysis using Pyrosequencing. Treatment with 5-aza-dC caused demethylation to varying degrees in each of the regions analyzed, with P4HTM demonstrating ~50% demethylation (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, small populations of RD cells treated with 5-aza-dC changed their morphology, became multi-nucleated, and expressed myosin heavy chain, consistent with myotube formation (Fig. S1). This finding suggests that epigenetic silencing by DNA methylation blocks RD cells from being able to differentiate and that this block can be partially overcome with 5-aza-dC treatment.

Figure 2. Repression of IRX1, P4HTM, and DNAJA4 is alleviated by 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine treatment. RD cells were treated with either 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC) or vehicle alone for 72 h and RNA was analyzed by reverse transcriptase-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). (A) Fold change of mRNA expression of RD cells treated with 5-aza-dC or normal skeletal muscle (SKM) as compared with untreated RD cells. Error bars represent standard deviations. (B) 5-aza-dC treatment causes demethylation of promoter CpG islands. Quantitative DNA methylation was determined using Pyrosequencing from bisulfite converted DNA from normal skeletal muscle (SKM) and RD cells (+/− 5-aza-dC). Percent methylation for 4–6 contiguous CpG dinucleotides (denoted by either a red Y or R in the analyzed sequence, depending on the strand sequenced) for each gene is shown. The genomic regions subjected to Pyrosequencing are shown by the red rectangles in the gene diagrams in Figure 1.

Aberrant DNA methylation is shared between RMS cell lines and primary patient samples

We then performed the DAMD assay on 10 primary pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma patient samples, 5 classified as embryonal and 5 as alveolar (Table 1). Almost 1300 promoter regions were DAMD-positive in one or more of the RMS patient samples when compared with skeletal muscle (Table S1). The RMS samples ranged from 39 to a high of 642 hypermethylated regions in a single RMS sample. Approximately 140 of these promoter regions are hypermethylated in 4 or more samples.

Table 1. Clinical information for the primary rhabdomyosarcoma patient samples including the subtype, age and gender of patient at sampling, and number of DAMD-positive loci determined in this study.

| |

|

|

|

Polycomb group target genes (2094 Entrez IDs) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient ID | Subtype | Age/Sex | DAMD-positive loci | overlap | p value |

| 6959 |

aRMS |

6/F |

473 |

86 |

1.56E-07 |

| 9162 |

aRMS |

18/M |

145 |

39 |

1.63E-08 |

| 9200 |

aRMS |

19/M |

642 |

107 |

4.81E-07 |

| 9203 |

aRMS |

19/F |

142 |

25 |

5.83E-03 |

| 9278 |

aRMS |

9/M |

332 |

59 |

2.68E-05 |

| 0032 |

eRMS |

ND |

364 |

45 |

1.23E-01 |

| 0369 |

eRMS |

ND |

39 |

9 |

1.64E-02 |

| 1194 |

eRMS |

3/F |

266 |

49 |

4.91E-05 |

| 4053 |

eRMS |

12/F |

274 |

33 |

2.06E-01 |

| 9207 |

eRMS |

4/M |

86 |

16 |

1.48E-02 |

| |

All samples |

|

1289 |

200 |

2.22E-09 |

| |

All eRMS |

|

714 |

99 |

1.66E-03 |

| All aRMS | 1018 | 170 | 1.58E-10 | ||

The table also shows the level of enrichment for Polycomb group target genes for each of the patient samples, as well as aggregate data for the embryonal (eRMS), alveolar (aRMS), and all of the samples.

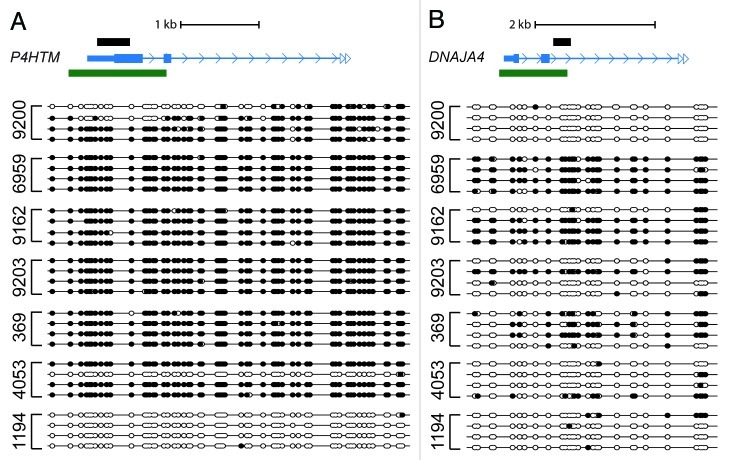

Similar to the RMS cell lines, the P4HTM, IRX1, and DNAJA4 promoters gave DAMD-positive signals in the primary patient samples, with 3 of 10 being positive at P4HTM, 2 of 10 at IRX1, and 4 of 10 at DNAJA4. We were able to perform bisulfite sequence analysis on 7 of the patient samples interrogating the same genomic regions of P4HTM and DNAJA4 analyzed in the RMS cell lines. P4HTM was actually hypermethylated in 6 of the 7 patient samples (Fig. 3A), while DNAJA4 was hypermethylated in 3 of 7 samples, with evidence of a lesser degree of methylation in 2 of the other patient samples (Fig. 3B). Based on our bisulfite sequence analysis confirmation of DAMD-positive loci in previous work,14 the statistical cut-offs we have employed yield very few false positives. As expected, however, false negatives will be higher, as demonstrated by the difference in DAMD-positive and bisulfite sequence analysis confirmed samples for P4HTM. The finding that a subset of hypermethylated loci identified in the RMS cells also occur in primary patient samples suggests that these loci are not simply the result of an in vitro selection bias, but rather represent genes that could be instrumental for the pathogenesis of rhabdomyosarcoma.

Figure 3.P4HTM and DNAJA4 are methylated in a subset of primary rhabdomyosarcoma patient samples. (A,B) Bisulfite sequence analysis of P4HTM and DNAJA4 (same genomic region as shown in Figs. 1C and 1D) is shown. See Figure 1 legend for labeling schematic.

We also observed DAMD-positive signals in the promoter regions of other genes implicated in development and carcinogenesis. A DAMD-positive signal was observed for GATA4 (2 patient and 2 cell lines), GATA6 (5 patient and 3 cell lines), HES5 (5 patient and 1 cell line), ALX3 (1 patient and all 4 cell lines), and BMP8A (1 patient and 3 cell lines). Bisulfite sequence confirmation was performed on a subset of the patient samples for ALX3 and all of the cell lines for ALX3 and BMP8A, and this data agreed with the DAMD-positive signals on the arrays (Fig. S2).

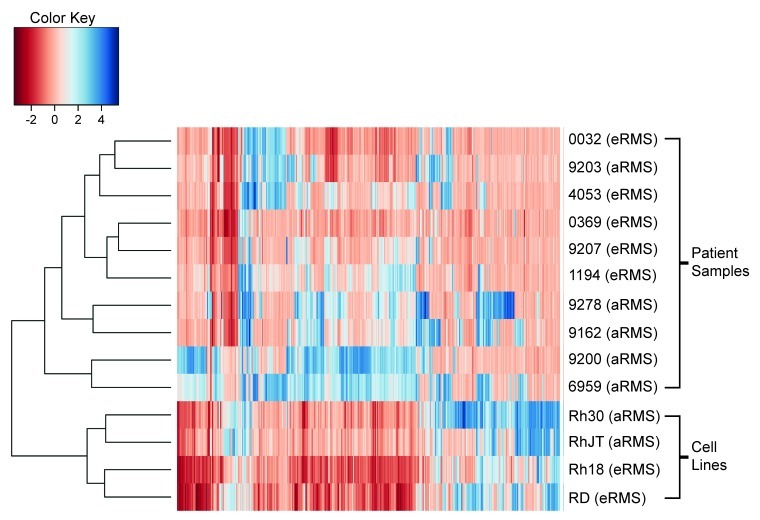

Cluster analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation identifies rhabdomyosarcoma subtype

To determine if DNA methylation patterns correlated with histological subtype of rhabdomyosarcoma, unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis was performed on the 10 patient samples as well as the four RMS cell lines (Fig. 4). The four cell lines clustered with one another, with the alveolar (Rh30 and RhJT) and embryonal (RD and Rh18) forming separate subgroups. Interestingly, the DNA methylation profiles of the patient samples also showed a trend to cluster based on histological subtype. The 5 embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (eRMS) patient samples form a cluster, with one of the alveolar (aRMS) patient samples also included. The alveolar samples have a grossly higher level of methylation with the 4 remaining patient samples forming two distinct clusters. These results suggest that DNA methylation may serve a role in subtype stratification of rhabdomyosarcomas.

Figure 4. Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis of DNA methylation correlates with rhabdomyosarcoma subtype. Cluster analysis of the 4 RMS cell lines and 10 RMS patient samples.

Primary aRMS samples show enrichment of Polycomb group target genes

Polycomb group (PcG) proteins regulate developmentally appropriate expression of genes required for tissue differentiation. PcG proteins act in coordinated polycomb repressor complexes (PRC1 and PRC2) to silence genes by H3K27 methylation and DNA methylation. Previous studies have demonstrated that targets of PcG repressor complexes are aberrantly methylated in cancer. To determine if this occurs in RMS, we utilized a previously identified set of PcG H3K27 target genes based on chromatin immunoprecipitation against PRC2 components SUZ12 and EZH2.15,16 The PcG targets identified in those studies mapped to 2094 unique Entrez IDs out of the 20,176 spotted on our arrays. Enrichment testing showed enrichment of hypermethylated PcG targets in both the embryonal cluster (99 Entrez IDs, p value 1.66 10−3) and the alveolar cluster (170 Entrez IDs, p = 1.58 10−10; Table 1). The enrichment of polycomb target genes is notably more significant in the alveolar cluster.

Discussion

In this study, we have performed a genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation in RMS, using both cell lines and patient samples. We found aberrant DNA hypermethylation in promoter CpG islands of many genes, many of which were shared among RMS cell lines and patient samples. For example, DAMD identified promoter methylation at IRX1, DNAJA4, and P4HTM in both the RMS cell lines and patient samples. These genes are expressed in normal skeletal muscle, but not RD cells, and the silencing of each may play a role in RMS pathogenesis.

DAMD identifies hypermethylated regions identified in other cancers

DNAJA4 is a DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog that is normally expressed in skeletal muscle but not RD cells. It is silenced by promoter methylation associated with c-Myc overexpression.17IRX1 is an Iroquois homeobox domain that has been suggested to act as a tumor suppressor in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma18 and gastric carcinoma.19ALX3 encodes a nuclear protein with a homeobox DNA-binding domain that functions as a transcriptional regulator involved in cell-type differentiation and development, and ALX3 promoter methylation is associated with advanced-stage neuroblastoma20 and has been found to be a potential colorectal cancer biomarker.21 The boundaries of methylation observed in the ALX3 promoter in the RMS samples are very similar to the boundaries observed in neuroblastoma. Members of the GATA gene family have been shown to be important for normal tissue differentiation and exhibit promoter DNA hypermethylation in cancer. GATA4 has been shown to be silenced by DNA hypermethylation in colorectal and gastric cancers,22 ovarian cancer,23 lung cancer,24 melanoma,25 and malignant astrocytoma,26 while GATA6 hypermethylation has been shown to correlate with poor outcome in glioblastoma multiforme.27HES5 is an effector of the Notch signaling pathway, and it’s expression is essential for the generation of neural stem cells.28 Recently, HES5 promoter methylation has been demonstrated in neuroblastoma, supporting a tumor suppressive role for the Notch signaling pathway in this tumor.29

Methylation dependent P4HTM silencing is a potential mechanism for HIF-1α stabilization in rhabdomyosarcomas

P4HTM is a member of a family of prolyl 4-hydroxylases that can catalyze the conversion of proline residues to 4-hydroxyproline. This family can be further subdivided into members that either act on collagen to drive the assembly of triple helical molecules, or those that act on the α subunits of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) to target them for degradation by the von Hippel-Lindau E3 ubiquitin ligase complex under normoxic conditions.30 While P4HTM shares sequence homology to those prolyl hydroxylases that act on collagen, both in vitro and in vivo experiments have demonstrated that the preferred substrate for P4HTM appears to be the oxygen-dependent destruction domain of the α subunits of HIF. Studies in a neuroblastoma cell line have shown that overexpression of P4HTM hydroxylates HIF-1α, targeting it for destruction; conversely, siRNA against P4HTM results in increased HIF-1α levels.31 Our findings that P4HTM is not expressed in RD cells suggests that P4HTM silencing by promoter DNA methylation is a potential mechanism for HIF-1α stabilization in rhabdomyosarcomas.

The hypoxic stress response is activated in a wide variety of cancers, and increased HIF-1α expression correlates with poor prognosis.30 Recently, the glycolytic inhibitor 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) was shown to preferentially induce apoptosis in alveolar vs. embryonal RMS cell lines.32 Resistance to 2-DG, however, can be caused by increased HIF-1α levels.33 Future experiments exploring how P4HTM might regulate HIF-1α levels may yield important clinical information to guide therapy with this agent. Combining 2-DG with 5-aza-dC may increase the sensitivity of RMS cells to apoptosis.

Alveolar and embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas form distinct clusters based on methylation signature with significant enrichment of PcG targets in the alveolar cluster

Alveolar and embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas are often heterogeneous and not clearly identifiable based on histology. While 80% of alveolar tumors are characterized by a PAX:FOXO1 fusion protein, the remaining 20% of fusion negative alveolar tumors are more difficult to characterize. Using a relatively small patient size of 10 samples, we see a tumor subtype specific methylation pattern emerge. While we did not have fusion status for the patient samples used in this study, it is interesting to note that 4 of the alveolar patient samples formed two distinct clusters (Fig. 4). These DNA hypermethylation patterns could reflect distinct biological characteristics of alveolar tumors driven by either different PAX:FOXO1 fusion proteins or the absence of these translocations (fusion negative aRMS). More patient samples with associated clinical outcome data are necessary to evaluate the association between methylation clusters, histologically identified subtype, treatment response, and survival.

PcG target genes involved in tissue specific differentiation frequently exist in a bivalent chromatin state in stem cells with both activating H3K4me3 and repressive H3K27me3 histone modifications.6 As a cell commits to a particular lineage, these bivalent marks are resolved into either active or repressive histone modifications. Expression of genes required for the differentiation of a given cell type acquire active chromatin marks while the repressive H3K27me3 mark is maintained at genes required for pluripotency or differentiation into other tissue types. Subsequent recruitment of DNA methyltransferases by EZH2 to these regions of H3K27me3 marked chromatin is thought to provide a ‘lock’ specifying a given tissue.

Of the DAMD-positive polycomb target genes identified in our study of RMS, most are associated with tissue subtypes other than skeletal muscle, and the majority are associated with neural development. Interestingly, H3K27me3 is enriched at the promoters of PcG target genes involved with neural cell fate specification during the process of normal myogenesis.34 The increased DNA methylation at these same regions observed in RMS may be a result of EZH2-mediated recruitment of DNA methyltransferases to H3K27me3 marked chromatin. In support of this hypothesis, EZH2, as in a wide variety of other cancers, is overexpressed in RMS cell lines and patient samples.35 In addition, the inappropriate expression EZH2 in RMS may contribute to cell proliferation, since the process of normal skeletal muscle differentiation requires the downregulation of EZH2.36

Our pilot study of DNA methylation changes in RMS suggests that this epigenetic modification likely plays a role in the pathogenesis of rhabdomyosarcoma. Treatment of RD cells with the demethylating agent 5-aza-dC can result in differentiation of a subpopulation of these cells, suggesting that aberrant methylation is repressing the expression of a gene, or genes, required for differentiation in RD cells. Previous work from our group suggests that RMS represent a state of arrested development in that RD cells can be forced to differentiate into myotubes by expressing a forced heterodimer between the myogenic master regulatory factor MyoD1 and E12.37 Our current study has identified novel hypermethylated promoter regions of genes that may act in the pathogenesis of RMS or potentially function as biomarkers for RMS.

Patients and Methods

RMS cell lines, patient samples, and immunofluorescence

RD, RhJT, Rh18, and Rh30 rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines and human HDF fibroblast lines were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep (Penicillin (final concentration 100 U/mL) and Streptomycin (final concentration 100 mg/mL (Gibco)). Differentiation media (DM) was DMEM supplemented with 1% Pen/Strep, 1% horse serum, insulin (final concentration 10 mg/mL), and transferrin (final concentration 10 mg/mL). RD cells were treated with 30 µM 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC; Sigma) from a 2 mM stock dissolved in DMSO at 12-h intervals for 72 h total before harvesting of DNA and RNA. Ten de-identified primary tumor samples were obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network. Normal adult skeletal muscle genomic DNA was obtained from Biochain. Genomic DNA was isolated from the RMS cell lines and patient samples using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and immunostained for myosin heavy chain using MF20 antibody (1:250, supernatant).38

DAMD assay

The DAMD assay was performed on 2 µg of genomic DNA and analyzed as previously described.14 Two replicates were used for each sample. Raw data was scaled to a target intensity of 100 and normalized by quantile normalization. A Wilcoxon Rank Sum two-sided test was performed over a sliding window of 250 bp to generate peaks. A maximum gap of ≤ 100 bp and minimum run of > 30 bp was used to generate signal and p-value thresholds (log2(signal ratio) > 1.2 and p < 0.001). Data was displayed using the Integrated Genome Browser (v 5.12, Affymetrix), and bed files were generated with the location of each peak. Peaks were mapped using NimbleScan software (v2.4) -7 kb to +1.5 kb of the transcriptional start site to generate candidate gene lists.

Bisulfite DNA conversion, PCR and sequence analysis

One µg of human genomic DNA was converted using the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer’s instructions. 20% of this conversion reaction was used in a PCR reaction using FastStart Taq (Roche). Reaction conditions were: 5 µL GC rich solution, 2.5 µL 10x Buffer, 0.3 µL FastStart Taq, 2.5 µL 2.5 mM dNTPs, 4 µL bisulfite converted DNA, 1 µL each 10 µM primer, 8.8 µL dH2O with the following cycling conditions: 96°C 6:00 followed by 5 cycles of (96°C 0:45, 50°C 1:30, 72°C 2:00) followed by 30 cycles of (96°C 0:45, 50°C 1:30, 72°C 1:30) with a 7:00 72°C final extension. See Table 2 for primer sequences. PCR fragments were isolated on 1% agarose in TBE gels and extracted using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer’s instructions. To elute, 20 µL of buffer EB was used, and 4 µL of eluted product was cloned using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit for Sequencing (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Clones were grown overnight in LB supplemented with 100 µg/mL carbenicillin. DNA was isolated from individual cultures using the QIAprep Miniprep Kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was prepared for sequencing using the following protocol. 200 ng plasmid DNA, 2 µL Big Dye Terminator reagent (Applied Biosystems), 1 µL 10 µM m13rev primer, 0.5 µL 50% DMSO, and 4.5 µL H2O with the following cycling conditions: 95°C 5:00, and 27 cycles (95°C 0:10, 50°C 0:05, 60°C 4:00). Samples were analyzed by ABI capillary sequencing in the FHCRC shared resources center. Alternatively, the University of Washington High-Throughput Genomics Unit was used. Sample ABI files were analyzed using Sequencher (Gene Codes) and MethTools.39

Table 2. Primers used in this study.

| Primers for RT-qPCR | Sequence |

|---|---|

| AA_94hTimm17b |

GGAGCCTTCACTATGGGTGT |

| AA_95hTimm17b |

CACAGCATTGGCACTACCTC |

| qDNAJA4_F2 |

TGGCCCTCCAGAAAAATG |

| qDNAJA4_R2 |

ACTTCTCCACCGATCCCTTC |

| qIRX1_F1 |

GGCACTCAATGGAGACAAGG |

| qIRX1_R1 |

TGGAAGGGCGACTTTAACTG |

| qP4HTM_F1 |

AGGCAATGAGCACTATGCAG |

| qP4HTM_R1 |

GTCATCCACCATCCATTTCC |

| Primers for bisulfite PCR | Sequence |

|---|---|

| hs.bis.Bmp8A.F1 |

GATTGGTTGATAGTTTTAGTTTTTAG |

| hs.bis.Bmp8A.R1 |

AACCCTTAAACCTTCCCTAACC |

| hs.bis.Alx3.F5 |

GTTTTATTTTTTTTTGAGTTGTTTGGGAT |

| hs.bis.Alx3.R5 |

ACTCTAAAAAATAAAACTCCAAAAACCC |

| hs.bis.P4htm.F1 |

TTTAGTTTGGGAAGAGAAGTTTTAG |

| hs.bis.P4htm.R1 |

CACCATCAACACCAAAAAATAAAC |

| hs.bis.Irx.F2 |

GTTTTTTTYGTAGTTGGGTTATT |

| hs.bis.Irx.R2 |

RAACCTTTCTAATTCCTCTT |

| hs.bis.Dnaja4.F3 |

GGGGTTAAGGGTTATTAAGTTAGGAG |

| hs.bis.Dnaja4.R3 |

AAAAAACCAACACACCCTATAAAAAC |

| Primers for PyroMark PCR | Sequence |

|---|---|

| DNAJA4_Pyro_F |

GTTTGTTGGGGAGGTTGT |

| DNAJA4_Pyro_R |

ACCCAAATACCCCACCACATACCT |

| IRX1_Pyro_F |

GGGTGAGATAGAGGAGAAG |

| IRX1_Pyro_R |

CCCAACTACAACCCCTTCCTACCCTA |

| Primers for PyroMark Sequencing | Sequence |

|---|---|

| DNAJA4_Pyro_Seq |

AATCTCCCCCCACCTCTA |

| IRX1_Pyro_Seq | GGGAGGTAGGGAGTATTTATTATTT |

Total DNA/RNA isolation, RT-qPCR, and Pyrosequencing DNA Methylation analysis

Human DNA and RNA from the same cells were isolated using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit and QIAshredder homogenization (Qiagen) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Human adult skeletal muscle total RNA was obtained from Biochain. cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using the Invitrogen Superscript III reverse transcriptase (RT) kit protocol per the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using 3 µL of each RT reaction, 10 µl FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Rox) (Roche), 0.6 µL 10 µM forward and reverse primers, and 7.4 µL H2O. Reactions were performed in an ABI 7900HT machine (40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec followed by 60°C for 1 min). Inputs were normalized using Timm17b. Expression of each gene in RD cells + 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine for 72 h in GM and 48 h in DM (experimental) relative to untreated RD cells (control) was measured using change in Ct value. Experiments were performed in triplicate and the Ct value of the control was averaged. The ΔCt and fold-change (2^ΔCt) for each experiment relative to the averaged control was calculated. The average and standard deviation are presented. For quantitative DNA methylation analysis using Pyrosequencing, PyroMark CpG Assays were performed per the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). Custom primers used for the bisulfite PCR and subsequent sequencing reactions were designed using the PyroMark Assay Design 2.0 software for DNAJA4 and IRX1, while P4HTM analysis was performed using primers obtained from Qiagen (Hs_AC137630.3_01_PM PyroMark CpG Assay). Briefly, 20 ng of bisulfite converted DNA was used as template using the PyroMark PCR Kit and PCR products were analyzed using a PyroMark Q24 instrument. See Table 2 for primer sequences.

Cluster and PcG target gene enrichment analysis

Peaks for a given sample were defined as regions with three or more consecutive probes with a p ≤ 0.001. Probes with p ≤ 0.001, a log2(signal ratio) > 1.2, and present within peaks were defined as hypermethylated probes. Hierarchical clustering using the top 4000 hypermethylated probes with the biggest variance across all samples was used. The Bioconductor gplots package was used for clustering analysis and plotting. Hypermethylated probes were assigned to an Entrez gene ID if they were within -7 kb to +1.5 kb of a gene’s transcriptional start site. Fisher's exact test was used to determine the p-value for enrichment using a PcG target gene list of 2094 unique Entrez IDs.16

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Acknowledgments

SEM was supported by the University of Washington Medical Scientist Training Program. Z.Y. was supported by the NIH Interdisciplinary Training Program in Cancer (T32 CA080416). S.J.D. was supported as a St. Baldrick’s Foundation and Hyundai Hope on Wheels Scholar. This study was also supported by NIAMS AR045113 (S.J.T.).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- RMS

rhabdomyosarcoma

- DNAJA4

DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 4

- HES5

Hairy and enhancer of split 5

- IRX1

Iroquois homeobox 1

- BMP8A

Bone morphogenetic protein 8A

- GATA

GATA-binding protein

- P4HTM

Prolyl 4-hydroxylase, transmembrane (endoplasmic reticulum)

- ALX3

Aristaless-like homeobox 3

- PAX

Paired box gene

- FOXO1

Forkhead box O1

- Fkhr

Forkhead

- DAMD

denaturation analysis of methylation differences

- aRMS

alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

- eRMS

embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma

- HOTS

H19 opposite tumor suppressor

- FGFR1

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1

- JUP

junction plakoglobin

- MYOD1

myogenic differentiation 1

- RASSF1

Ras association (RalGDS/AF-6) domain family member 1

- GO

gene ontology

- 5-aza-dC

5-aza-2-deoxycytidine

- PcG

polycomb group

- PRC2

polycomb repressive complex 1

- PRC1

polycomb repressive complex 2

- SUZ12

Suppressor of zeste 12 homolog

- EZH2

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2

- H3K27me3

Trimethylated histone 3 lysine 27

- H3K4me3

Trimethylated histone 3 lysine 4

- HIF

Hypoxia-inducible factor

- 2-DG

2-deoxyglucose

- E12

E2A immunoglobulin enhancer binding factor E12

- SKM

skeletal muscle

- UTR

Untranslated region

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/epigenetics/article/19463

References

- 1.Paulino AC, Okcu MF. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2008;32:7–34. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kikuchi K, Rubin BP, Keller C. Developmental origins of fusion-negative rhabdomyosarcomas. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2011;96:33–56. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385940-2.00002-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorensen PHB, Lynch JC, Qualman SJ, Tirabosco R, Lim JF, Maurer HM, et al. PAX3-FKHR and PAX7-FKHR gene fusions are prognostic indicators in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the children’s oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2672–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koufos A, Hansen MF, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Lampkin BC, Cavenee WK. Loss of heterozygosity in three embryonal tumours suggests a common pathogenetic mechanism. Nature. 1985;316:330–4. doi: 10.1038/316330a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onyango P, Feinberg AP. A nucleolar protein, H19 opposite tumor suppressor (HOTS), is a tumor growth inhibitor encoded by a human imprinted H19 antisense transcript. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16759–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110904108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berdasco M, Esteller M. Aberrant epigenetic landscape in cancer: how cellular identity goes awry. Dev Cell. 2010;19:698–711. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. Hypomethylation distinguishes genes of some human cancers from their normal counterparts. Nature. 1983;301:89–92. doi: 10.1038/301089a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein M, Meller I, Orr-Urtreger A. FGFR1 over-expression in primary rhabdomyosarcoma tumors is associated with hypomethylation of a 5′ CpG island and abnormal expression of the AKT1, NOG, and BMP4 genes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:1028–38. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gastaldi T, Bonvini P, Sartori F, Marrone A, Iolascon A, Rosolen A. Plakoglobin is differentially expressed in alveolar and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and is regulated by DNA methylation and histone acetylation. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1758–67. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen B, Dias P, Jenkins JJ, 3rd, Savell VH, Parham DM. Methylation alterations of the MyoD1 upstream region are predictive of subclassification of human rhabdomyosarcomas. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1071–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurmasheva RT, Peterson CA, Parham DM, Chen B, McDonald RE, Cooney CA. Upstream CpG island methylation of the PAX3 gene in human rhabdomyosarcomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44:328–37. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harada K, Toyooka S, Maitra A, Maruyama R, Toyooka KO, Timmons CF, et al. Aberrant promoter methylation and silencing of the RASSF1A gene in pediatric tumors and cell lines. Oncogene. 2002;21:4345–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lollini PL, De Giovanni C, Del Re B, Landuzzi L, Nicoletti G, Prodi G, et al. Myogenic differentiation of human rhabdomyosarcoma cells induced in vitro by antineoplastic drugs. Cancer Res. 1989;49:3631–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diede SJ, Guenthoer J, Geng LN, Mahoney SE, Marotta M, Olson JM, et al. DNA methylation of developmental genes in pediatric medulloblastomas identified by denaturation analysis of methylation differences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:234–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907606106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bracken AP, Dietrich N, Pasini D, Hansen KH, Helin K. Genome-wide mapping of Polycomb target genes unravels their roles in cell fate transitions. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1123–36. doi: 10.1101/gad.381706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalushkova A, Fryknäs M, Lemaire M, Fristedt C, Agarwal P, Eriksson M, et al. Polycomb target genes are silenced in multiple myeloma. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Licchesi JD, Van Neste L, Tiwari VK, Cope L, Lin X, Baylin SB, et al. Transcriptional regulation of Wnt inhibitory factor-1 by Miz-1/c-Myc. Oncogene. 2010;29:5923–34. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett KL, Karpenko M, Lin M-T, Claus R, Arab K, Dyckhoff G, et al. Frequently methylated tumor suppressor genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4494–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo X, Liu W, Pan Y, Ni P, Ji J, Guo L, et al. Homeobox gene IRX1 is a tumor suppressor gene in gastric carcinoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:3908–20. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wimmer K, Zhu Xx XX, Rouillard JM, Ambros PF, Lamb BJ, Kuick R, et al. Combined restriction landmark genomic scanning and virtual genome scans identify a novel human homeobox gene, ALX3, that is hypermethylated in neuroblastoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;33:285–94. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mori Y, Olaru AV, Cheng Y, Agarwal R, Yang J, Luvsanjav D, et al. Novel candidate colorectal cancer biomarkers identified by methylation microarray-based scanning. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18:465–78. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akiyama Y, Watkins N, Suzuki H, Jair KW, van Engeland M, Esteller M, et al. GATA-4 and GATA-5 transcription factor genes and potential downstream antitumor target genes are epigenetically silenced in colorectal and gastric cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8429–39. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8429-8439.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakana K, Akiyama Y, Aso T, Yuasa Y. Involvement of GATA-4/-5 transcription factors in ovarian carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2006;241:281–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo M, Akiyama Y, House MG, Hooker CM, Heath E, Gabrielson E, et al. Hypermethylation of the GATA genes in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7917–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen T, Kuo C, Nicholl MB, Sim M-S, Turner RR, Morton DL, et al. Downregulation of microRNA-29c is associated with hypermethylation of tumor-related genes and disease outcome in cutaneous melanoma. Epigenetics. 2011;6:388–94. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.3.14056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agnihotri S, Wolf A, Munoz DM, Smith CJ, Gajadhar A, Restrepo A, et al. A GATA4-regulated tumor suppressor network represses formation of malignant human astrocytomas. J Exp Med. 2011;208:689–702. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez R, Martin-Subero JI, Rohde V, Kirsch M, Alaminos M, Fernandez AF, et al. A microarray-based DNA methylation study of glioblastoma multiforme. Epigenetics. 2009;4:255–64. doi: 10.4161/epi.9130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hitoshi S, Ishino Y, Kumar A, Jasmine S, Tanaka KF, Kondo T, et al. Mammalian Gcm genes induce Hes5 expression by active DNA demethylation and induce neural stem cells. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:957–64. doi: 10.1038/nn.2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zage PE, Nolo R, Fang W, Stewart J, Garcia-Manero G, Zweidler-McKay PA. Notch pathway activation induces neuroblastoma tumor cell growth arrest. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pbc.23202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majmundar AJ, Wong WJ, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koivunen P, Tiainen P, Hyvärinen J, Williams KE, Sormunen R, Klaus SJ, et al. An endoplasmic reticulum transmembrane prolyl 4-hydroxylase is induced by hypoxia and acts on hypoxia-inducible factor alpha. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30544–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramírez-Peinado S, Alcázar-Limones F, Lagares-Tena L, El Mjiyad N, Caro-Maldonado A, Tirado OM, et al. 2-deoxyglucose induces Noxa-dependent apoptosis in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6796–806. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maher JC, Wangpaichitr M, Savaraj N, Kurtoglu M, Lampidis TJ. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 confers resistance to the glycolytic inhibitor 2-deoxy-D-glucose. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:732–41. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asp P, Blum R, Vethantham V, Parisi F, Micsinai M, Cheng J, et al. Genome-wide remodeling of the epigenetic landscape during myogenic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E149–58. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102223108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciarapica R, Russo G, Verginelli F, Raimondi L, Donfrancesco A, Rota R, et al. Deregulated expression of miR-26a and Ezh2 in rhabdomyosarcoma. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:172–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.1.7292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caretti G, Di Padova M, Micales B, Lyons GE, Sartorelli V. The Polycomb Ezh2 methyltransferase regulates muscle gene expression and skeletal muscle differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2627–38. doi: 10.1101/gad.1241904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Z, MacQuarrie KL, Analau E, Tyler AE, Dilworth FJ, Cao Y, et al. MyoD and E-protein heterodimers switch rhabdomyosarcoma cells from an arrested myoblast phase to a differentiated state. Genes Dev. 2009;23:694–707. doi: 10.1101/gad.1765109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bader D, Masaki T, Fischman DA. Immunochemical analysis of myosin heavy chain during avian myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:763–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grunau C, Schattevoy R, Mache N, Rosenthal A. MethTools--a toolbox to visualize and analyze DNA methylation data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1053–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.5.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.