Abstract

The maintenance of sister chromatid cohesion from S phase to the onset of anaphase relies on a small but evolutionarily conserved protein called Sororin. Sororin is a phosphoprotein and its dynamic localization and function are regulated by protein kinases, such as Cdk1/cyclin B and Erk2. The association of Sororin with chromatin requires cohesin to be preloaded to chromatin and modification of Smc3 during DNA replication. Sororin antagonizes the function of Wapl in cohesin releasing from S to G2 phase and promotes cohesin release from sister chromatid arms in prophase via interaction with Plk1. This review focuses on progress of the identification and regulation of Sororin during cell cycle; role of post-translational modification on Sororin function; role of Sororin in the maintenance and resolution of sister chromatid cohesion; and finally discusses Sororin’s emerging role in cancer and the potential issues that need be addressed in the future.

Keywords: cohesin, Eco1, Pds5, Plk1, sister chromatid cohesion and separation, Sororin, Wapl

Introduction

Replication of DNA at S phase and segregation of sister chromatids at anaphase are two vital processes required for cellular proliferation. Sister chromatid cohesion provided by cohesin and its associated proteins is essential to safeguard the accurate transmission of genome into two daughter cells. Cohesin is a multi-protein complex that is comprised of four core subunits, Smc1, Smc3, Rad21 and SA1/2, as well as a number of associated proteins that support cohesin function. The cohesin cycle includes loading of cohesin onto chromatin, establishment of cohesion between two sisters, cohesion maintenance, cohesin unloading and dissolution. Heterodimeric protein complex Scc2-Scc4, named kolerin,1 is responsible for cohesin loading in a replication licensing-dependent manner.2,3 Eco1/Ctf7 in yeast and orthologous Esco1 and Esco2 in vertebrates are required for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion by acetylating Smc3.4-6 Wapl in vertebrates, forming a complex with Pds5, called releasin,1 is necessary for the cohesin unloading in prophase.7,8 However, the maintenance of sister chromatid cohesion generated at S phase until its dissociation from chromatids in mitosis depends on Sororin, another cohesin-association protein.9 Recent studies indicate that Sororin, in addition to its function in the maintenance, also plays a regulatory role in the resolution of sister chromatid cohesion. Herein, we review the progress that has been made since its identification in 2001 in understanding the roles of Sororin in sister chromatid cohesion, separation and tumorigenesis.

Identification of Sororin

Human Sororin gene CDCA5 was identified from a meta-analytical gene expression screen of cell cycle-associated (CDCA) transcripts. Based on this screen, the CDCA5 gene product was predicted to function in the cell cycle, because it is closely co-expressed with known mitosis-regulating genes, such as Cdk1, cyclin B and Bub1.10 Sororin protein was identified from a screen for substrates of the Cdh1-activated anaphase-promoting complex (APCCdh1) in Xenopus, using an in vitro transcribed and translated protein expression system.9 APCCdh1 is a multi-subunit E3 ubiquitin ligase, which is activated from the initiation of anaphase and remains active in G1 phase.11 Sororin is degraded when recombinant Cdh1 is supplemented with Xenopus interphase egg extract. The KEN box domain on Sororin is responsible to target Sororin for APCCdh1-dependent degradation in a cell cycle-dependent manner.9

Sororin is a basic protein with a calculated isoelectric point (pI) of approximately 10. The predicted molecular size of Sororin is 27 kd, with an electrophoretic mobility of 35 kd on SDS‑PAGE.9 Early protein homology searches indicated that Sororin is conserved only in vertebrates. However, later studies employing iterative rounds of a similarity search in invertebrate proteome database using the C-terminal conserved region of vertebrate Sororin identified 18 protein sequences with significant similarity to Sororin.12 These protein sequences belong to 18 different metazoan species in nine taxa, including Insecta, Crustacean, Mollusca and Placozoa. Most of the protein sequences are hypothetical proteins. Only one of the 18 putative Sororin orthologs, Dalmatian from Drosophila, has been characterized. Dalmatian is a 95 kDa protein and plays roles in the development of the embryonic peripheral nervous system,13 mitotic spindle assembly14 and sister chromatid cohesion.12,15 Depletion of Dalmatian results in precocious sister chromatid separation and spindle checkpoint activation, similar to the function of Sororin.12 Based on sequence homology and functional studies, Dalmatian appears to be a Sororin ortholog, suggesting that Sororin is evolutionarily conserved in both invertebrates and vertebrates.

Is Eco1 a Sororin Ortholog in Yeast?

Although Sororin orthologs are found in lower eukaryotes, Sororin ortholog has not been identified in budding yeast S. cerevisiae. It is possible that the orthologous protein sequence is not conserved in S. cerevisiae, and, therefore, protein homology searches failed to identify it. Functional analysis may be an alternate way to identify Sororin ortholog in yeast. Another possibility is that a known protein plays the role of Sororin in addition to its other functions.

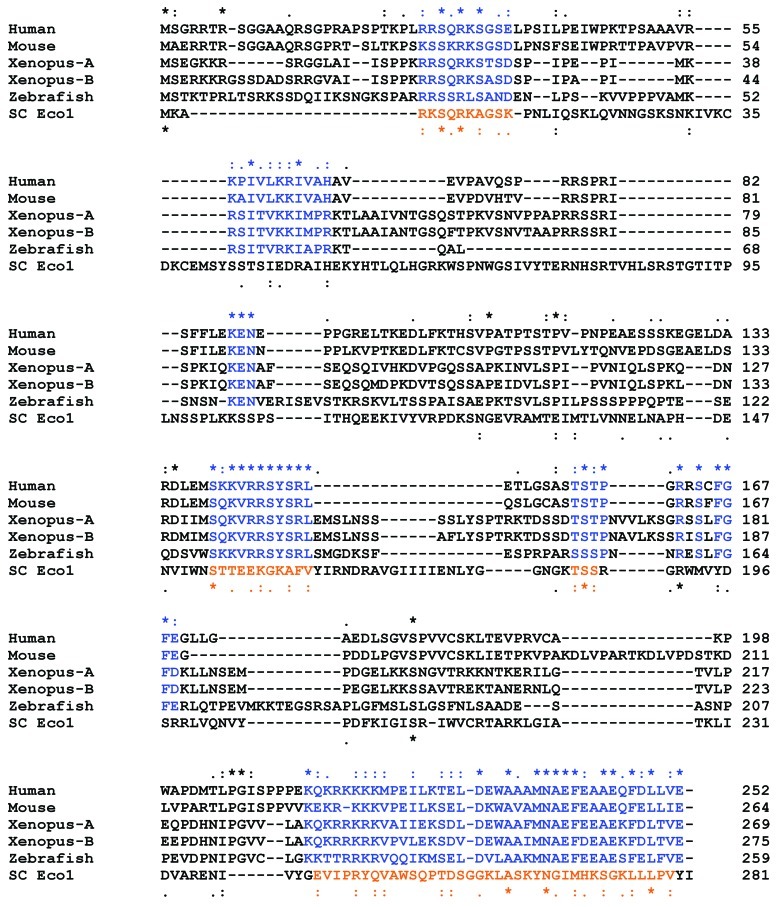

Although the N terminus of Sororin is less conserved compared with the C terminus in invertebrates, the region [26RRS QRK SGS E36] in the N terminus of human Sororin is well conserved among vertebrates (Fig. 1). When we used this conserved motif to perform WU-BLAST2 Search in the Saccharomyces Genome Database (http://www.yeastgenome.org/), surprisingly the only hit was Eco1. When S. cerevisiae Eco1 is aligned to the vertebrate Sororin, the conserved regions of Eco1 echo those of Sororin (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Clustal format alignment of Sororin and Eco1 by MAFFT L-INS-i (v6.843b) with manual adjustment. The top line indicates the conserved amino acids of vertebrate Sororin, whereas the bottom line shows the conserved amino acids of S. cerevisiae (SC) Eco1 with respect to vertebrate Sororin. The conserved regions among Sororin molecules from different species are shown in blue, whereas the region in SC Eco1 conserved relative to Sororin are shown in orange. Invariant, conserved and semi-conserved residues are indicated by an asterisk (*), colon (:) and period (.), respectively.

Eco1 is an acetyltransferase, which acetylates the two lysine residues (K112/113) of cohesin core subunit Smc3 in S. cerevisiae to generate sister chromatid cohesion.4-6 Yeast Eco1 is a small molecule with 281 amino acid residues, similar to the size of vertebrate Sororin. In contrast, vertebrate ortholog Esco1 is much larger than yeast Eco1, containing approximately 900 amino acid residues. Although yeast Eco1 is orthologous to vertebrate Esco1, it aligns well to only the last 300 amino acid residues of the vertebrate Esco1.16

One of the major roles of Sororin is to antagonize Wapl to maintain sister chromatid cohesion. This function is executed via Sororin’s FGF motif, which competes with Wapl’s FGF motifs to bind Pds5.12 The N terminus of vertebrate Wapl, containing FGF motifs,17 is unique to vertebrates and possibly functions as a regulatory domain. Unlike the vertebrate Wapl, the yeast ortholog Wpl1/Rad614,8 lacks the N terminus of vertebrate Wapl17 and, therefore, does not have FGF motifs. In vertebrates, most of cohesins dissociate from chromatids in prophase through a non-proteolytic phosphorylation-dependent manner (see below).18 In contrast, cohesins in yeast cells dissociate from chromosomes during metaphase-to-anaphase transition by Separase-mediated cleavage of cohesin-Scc1/Rad21.19 This difference, conceivably, is due to Sororin. Sororin and Wapl regulate the dissociation of cohesins from chromatids during prophase in vertebrates.12 Because S. cerevisiae does not have Sororin and/or Wpl1 lacks the regulatory FGF motifs, cohesins fail to dissociate from chromosomes in prophase. It is, therefore, tempting to suggest that Sororin and Wapl have functionally co-evolved in the vertebrates. In high eukaryotes, Wapl could have evolved from protein similar to the yeast Wpl1 by acquiring its FGF-containing N terminus and Sororin from a protein similar to yeast Eco1 to antagonize Wapl to regulate sister chromatid cohesion. One alternate hypothesis can be that originally both yeast and vertebrate Wapl had N termini; yeast Wpl1 lost its N terminus during evolution, precluding the functional requirement of a Sororin-like protein.

Sororin is Temporally and Spatially Regulated during Cell Cycle

Sororin protein level and its cellular localization vary with the stages of the cell cycle. Immunoblotting shows an increase in Sororin protein from S to G2 phase and a decline following mitotic exit.9,20 These findings have also been confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy.9,12,20 As that of the protein level, cellular localization of Sororin is also dynamic with cell cycle progression. Sororin is in nucleus from S to G2 phase, with its localization to chromatin. Once cells enter mitosis, Sororin dissociates from DNA and becomes cytosolic in prophase with no detectable staining on arm chromatids at metaphase. However, staining of extracted DNA indicates the presence of Sororin on centromeres in prophase, prometaphase and metaphase cells.12 Interestingly, Sororin re-associates with chromatids at late anaphase and telophase, which is observed with both immunofluorescence microscopy20 and live cell time-lapse imaging.21 Dissociation of Sororin from chromatin is regulated by phosphorylation. When the putative Cdk1/cyclin B phosphorylation sites are mutated into alanines to block phosphorylation, Sororin remains associated with chromatin until telophase. Mutations of the Cdk1/cyclin B phosphorylation sites have no apparent effect on the degradation of Sororin.21

The physiological significance of Sororin re-association with chromatin at late anaphase has not been determined. The localization of Sororin in cells from S phase to metaphase is similar to that of cohesin and is dependent on cohesin proteins.12 Although cohesin is known to re-associate with chromatin in telophase, whether the association of Sororin with chromatin in late anaphase is related to the cohesin remains to be elucidated.

In vertebrate cells, only a fraction of cohesins are destroyed by Separase at the transition from metaphase to anaphase. Most of cohesins dissociated from chromatids at prophase remain intact.18 These cohesins re-associate with chromosomes at late telophase and G1 phase when Sororin is degraded. At this stage of the cell cycle, dynamical association of cohesin with DNA is likely to regulate gene expression. The destruction and expression of Sororin in a cell cycle-dependent manner may be a possible mechanism to ensure that sister chromatid cohesion is generated only in S phase and is maintained until the beginning of anaphase. In this context, it will be interesting to examine the alterations in cell cycle progression and chromosomal segregation with the selective expression of the non-degradable Sororin with mutated KEN box.

In addition to binding to DNA, Sororin is localized to centrosomes and spindles from prophase to anaphase.20 Cohesin is known to localize on centrosomes/spindle poles22-27 and to interact with centrosome/spindle pole proteins.28-30 It has been reported that cohesin potentially functions as a centriole-engagement factor to regulate the centrosome cycle that is parallel to the chromosome cycle.31 Interestingly, the cohesin in centrosomes is regulated by known factors of sister chromatid cohesion, including Separase, Plk1 and Sgo1.26,31 It is, therefore, tempting to speculate that Sororin also functions on centrosome/spindle pole, which needs to be confirmed.

Sororin is Posttranslationally Modified by Phosphorylation

The mobility of Sororin reduces when cells enter mitosis, and the slow mobile (high molecular weight) Sororin band on immunoblot disappears when cells exit the mitosis.9,20 Whether the disappearance of slow-mobile Sororin band is due to dephosphorylation and/or degradation is unclear. Because the total level of Sororin protein is reduced at G1,9,20,32 the phosphorylated Sororin likely is degraded by proteasome following ubiquitination by APCcdh1.9 Interestingly, the fast mobile Sororin band is found persistent throughout the entire cell cycle.9,20 This persistence may be caused by cells that are not completely synchronized, or because the nonphosphorylated Sororin cannot be degraded. The later scenario would suggest that Sororin phosphorylation is required for the cell cycle-dependent ubiquitin proteasome-mediated degradation of Sororin.

There are 33 predicted phosphorylation sites on Sororin.20 All the putative phosphorylation sites are in the N terminus and middle part of Sororin. Among the 33 putative phosphorylation sites, 21 sites have been confirmed.9,20,33-38 However, the corresponding kinases that phosphorylate each of these sites on Sororin are difficult to determine. To date, only two kinases (Cdk1/cyclin B and ERK2) have been verified to phosphorylate Sororin.20,21,39

The minimum consensus sequence for Cdk1/cyclin B phosphorylation is (S/T)P and the full consensus sequence is (S/T)Px(K/R).40-42 There are six putative minimum consensus sequences (T,48 S79, T111, T115, S181 and S209) and three full consensus sequences (S21 S75 and T159) of Cdk1/cyclin B phosphorylation in Sororin.20,21 Except the site at S181, all the other eight sites have been confirmed by mass spectrometry using in vitro Cdk1/cyclin B assay (Table 1). The phosphorylation of S181 site also could not be confirmed in in vivo assays.20 In vitro Cdk1/cyclin B phosphorylation indicates that S21, S75 and T159 are the major phosphosites, which accounts for 90% of the total phosphorylation of Sororin by Cdk1/cyclin B.20 Sororin mutants with all the putative Cdk1/cyclin B phosphorylation sites are poorly phosphorylated by Cdk1 in vitro. Sororin mobility shift is reduced significantly when Cdk1 activity is blocked using inhibitor purvalanol A in cells,21 suggesting that Cdk1 is a key kinase to phosphorylate Sororin.

Table 1. Mass spectrometry analysis of Cdk1/cyclin B Phosphorylation sites on Sororin WT and S21A mutant.

| Phosphorylation sites | Sororin WT (# peptides recovered) |

Sororin S21A (# peptides recovered) |

Consensus Sequence of Cdk1/cyclin B Phosphorylation Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| S21 |

12 |

0 |

SPTK |

| T23 |

0 |

1 |

|

| T48 |

10 |

3 |

TP |

| S50 |

1 |

1 |

|

| S75 |

42 |

30 |

SPRR |

| S79 |

2 |

1 |

SP |

| T111 |

10 |

6 |

TP |

| T113 |

1 |

1 |

|

| S114 |

1 |

0 |

|

| T115 |

11 |

5 |

TP |

| S139 |

1 |

1 |

|

| S158 |

2 |

2 |

|

| S159 |

8 |

6 |

TPGR |

| S209 | 12 | 6 | SP |

Recombinant Sororin WT and S21A mutant were phosphorylated by Cdk1/cyclin B, and the phosphorylated sites were identified by mass spectrometry.20 The total number of peptides for each site is shown in the table. A total of 17 putative phosphorylation sites were identified, and 13 were verified in Sororin WT. In contrast, in Sororin S21A mutant, a total of 14 putative phosphorylation sites were identified and 12 were experimentally verified.

Wild-type (WT) Sororin protein dissociates from chromatin when cells enter prophase. Sororin is hardly detectable on metaphase chromatids, but it re-associates with chromatin at late anaphase and again disappears at late telophase.20,21 Similar to WT Sororin, the majority of Sororin Cdk1/cyclin B phosphorylation mutants release from chromatin at prophase, suggesting this release is not solely dependent on the phosphorylation by Cdk1/cyclin B. However, unlike WT Sororin, Sororin with mutations at all the nine putative Cdk1 cyclin B phosphorylation sites remains on chromatin until the end of telophase,21 indicating phosphorylation is a critical factor in regulating the dissociation of Sororin from chromatin.

Another kinase that phosphorylates Sororin is ERK2. Recombinant human Sororin can be phosphorylated by ERK2 in vitro. Epidermal growth factor (EGF)-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1 and ERK2 also leads to the phosphorylation of Sororin, which can be inhibited by U0126, an MEK/ERK inhibitor. Mass spectrometry analyses indicate that EGF induces the phosphorylation of Sororin at S79 and S209. Substitution of S79 and S209 residues with alanine abolishes EGF-stimulated phosphorylation, similar to the effect of EGF plus U0126 treatment, confirming that Sororin is indeed phosphorylated by ERK at S79 and S209.39

In in vitro assays, Sororin is phosphorylated by Plk1, but the phosphorylation sites remain to be identified.20 The role of phosphorylation on Sororin function is yet to be fully defined. Because more than 30 putative phosphorylation sites are found on Sororin, more kinases that phosphorylate Sororin most likely will be identified. Phosphorylation at different sites on Sororin at different stages of the cell cycle may be the key to regulate its dynamic localization and cellular function.

Sororin is Required for the Sister Chromatid Cohesion

Depletion of Sororin arrests HeLa cells at prometaphase, with dispersed chromatids along the spindle, a phenotype reminiscent of Rad21 knockdown.9 Metaphase chromosome spread further shows that sister chromatid cohesion is lost in the cells with Sororin depletion. The precocious chromatid separation (PCS) phenotype can be rescued by overexpressing Sororin,9,20 suggesting Sororin is required for sister chromatid cohesion.

The role of Sororin in sister chromatid cohesion is further supported by the evidence from Xenopus egg extract. Sororin overexpression in in vitro DNA replication and separation system using Xenopus egg extract increases the amount of cohesin along the sister chromatids.9 Furthermore, after one cell of the two-cell Xenopus embryo is injected with Sororin RNA, the embryonic cells divide normally until stage 9, when the cells on the injection side stop dividing. DNA staining indicates that the embryonic cells derived from the injected cell show CUT phenotype (i.e., defects in DNA segregation). The phenotype includes some cells with no DNA, whereas the others with DNA are trapped between daughter blastomeres.9 These data suggest that Sororin is essential not only for the sister chromatid cohesin but also for the chromosome separation.

Because Sororin depletion results in a PCS phenotype at prometaphase, it was postulated that Sororin plays a role in maintaining sister chromatid cohesin. However, later studies revealed that Sororin is also required for sister chromatid cohesion in S and G2.12,44 When HeLa cells were synchronized at S phase and Sororin was knocked down with siRNA, the distance between the arms of the sister chromatid in Sororin-depleted cells was found to be twice that of the control cells, indicating that without Sororin, sister chromatid cohesion fails to maintain. Moreover, the cells with Sororin depletion take approximately 1.5 h longer to reach nuclear envelope breakdown than the control cells.12 The delay of nuclear envelope breakdown possibly is caused by slowing down of the cell cycle due to loss of cohesin and/or the defect of DNA damage repair,40,44 ultimately resulting in the activation of DNA-damage checkpoint and delayed cell cycle progression.

Sororin Interacts with Cohesin

Sororin co-immunoprecipitates cohesin complex, consisting of Rad21, Smc1, Smc3 and SA1/2, as well as cohesin-associated protein Pds5A/B and Wapl.9,12 However, the specific cohesin core subunit with which Sororin interacts is not currently known. In view of Sororin’s vital function in chromosomal cohesion, it was predicted that the regions of Sororin interacting with cohesin and its associated proteins would be conserved in Sororin orthologs from different species. Alignment of Sororin orthologs from several vertebrate species reveals seven short motifs (Fig. 1): [26RRS QRK SGS E36], [55KPI VLK RIV AH66] and a KEN box [87KEN90] in the N terminus of Sororin; [138SKK VRR SYS RL149], a Plk1 binding motif [156(S/T)S(S/T)P160] and an invariant FGF motif [161RxSxFGF(D/E)169] in the middle part of Sororin and a Sororin domain containing an arginine/lysine-rich region from amino acid residues 214 to 222 and an acidic amino acid-rich stretch from 237 to 252 in the C terminus of Sororin (numbering refers to the human Sororin sequence). The Sororin domain is unique to all Sororin proteins.12

Except the KEN box, which targets Sororin for APCcdh1-mediated degradation,9 the other two conserved domains on the N terminus have not been characterized. The N-terminal 90 amino acids truncated Sororin protein not only interacts with cohesin as efficiently as wild type, but also rescues PCS caused by endogenous Sororin depletion as that of WT.45 Because the KEN box and several phosphorylation sites20 are in this region, the N terminus of Sororin may play a regulatory role, particularly in Sororin localization, which requires further investigation.

The three conserved domains in the middle portion of Sororin have been characterized. [138SKK VRR SYS RL149] interacts with cohesin. Deletion of this domain reduces the interaction of Sororin and cohesin, similar to the loss of the last 16 aa of Sororin. Interestingly, Sororin without this domain functions normally as wild type in rescuing the PCS phenotype, which seems contradictory to the data suggesting that this 11 amino acid region is important for Sororin-cohesin interaction.45 Although this [138SKK VRR SYS RL149] domain may function in chromatin binding by collaborating with other regions,45 its exact role remains to be defined.

[156(S/T)S(S/T)P160] is a Plk1 binding motif.20 The polo-box domain of Plk1 binds to the consensus motif S(S/T)P after the middle S/T is phosphorylated by Cdk1/cyclin B. Human Sororin interacts with Plk1 via its ST159P. When the threonine residue is mutated to alanine (T159A), Sororin fails to interact with Plk1 and the resolution of chromosome arm cohesion is inhibited,20 suggesting that Plk1 regulates dissociation of cohesin from chromosome arms via interacting with Sororin.

When the two phenylalanine residues in the FGF motif on Sororin are mutated into alanine, Sororin-cohesin interaction remains unaffected, but maintenance of cohesion is disrupted.12 Unlike the WT Sororin, recombinant Sororin FGF mutant protein cannot rescue the cohesion defect caused by immunodepletion of endogenous Sororin in the Xenopus egg extract system. Moreover, recombinant WT Sororin causes “overcohesion,” whereas the mutant does not, further supporting the notion that FGF motif is essential for cohesion.12 However, the above studies are not consistent with the finding in HeLa cells in which Sororin FGF mutant can rescue the PCS caused by endogenous Sororin depletion.45 This disparity may be due to different experimental systems used and, therefore, warrants further investigation.

The C-terminal Sororin domain is responsible for the interaction with cohesin. Deleting the last 16 amino acids or mutating two of the last 16 amino acids into alanine (F241A, F247A) severely reduces the interaction of Sororin and cohesin, whereas deletion of the last 39 amino acids (from 214 to 252 aa) of Sororin completely abrogates the Sororin-cohesin interaction.45 Depletion of Sororin with siRNA or shRNA results in mitotic arrest and PCS. This phenotype can be rescued by expression of wild-type Sororin.20,45 As expected, Sororin with a mutated or deleted C terminus fails to rescue the loss of cohesion induced by endogenous Sororin depletion. Systematic analyses are necessary to identify which cohesin subunit interacts with Sororin and through which domains this interaction occurs. It is also interesting to know how this interaction influences the nuclear localization of both Sororin and cohesin and prevents PCS.

Recruitment of Sororin to Chromatin

In S phase, Sororin is expressed and associates with chromatin during DNA replication. In vertebrate cells, sister chromatid cohesion is generated when cohesin core subunit Smc3 is acetylated by establishment of cohesion (Eco) protein during DNA replication. Because association of Sororin with chromatin coincides with DNA replication and establishment of cohesion, cohesin and Eco protein are postulated to regulate the binding of Sororin to chromatin.

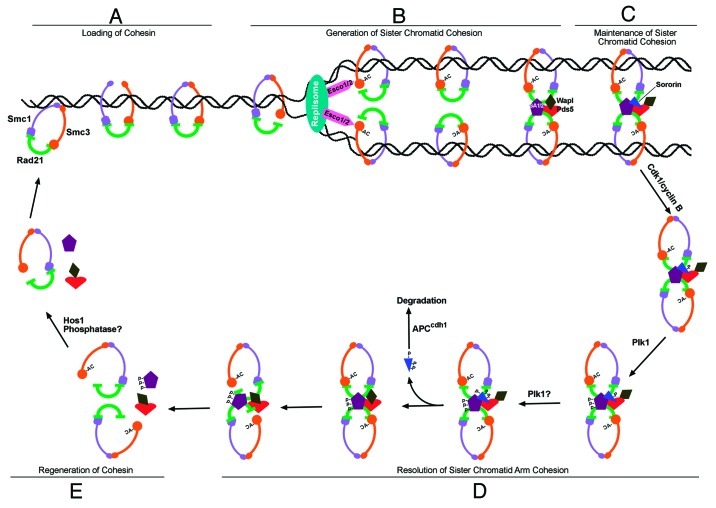

Is cohesin required for the recruitment of Sororin? During DNA replication in Xenopus interphase oocytes extract system, depletion of Sororin does not affect the association of cohesin to chromatin. In contrast, depletion of cohesin before DNA replication significantly reduces the association of Sororin to chromatin,16 suggesting that the association of Sororin relies on cohesin. Because cohesin depletion does not affect Sororin expression, the reduction of chromatin-bound Sororin cannot be attributed to the loss of Sororin.12 Furthermore, inhibition of cohesin association with chromatin also blocks Sororin recruitment to chromatin. Cohesins are recruited to chromosomes in telophase during replication licensing2,3 (Fig. 2A). Blocking licensing by geminin, a cell cycle-regulated protein that prevents the assembly of the origins of replication,46,47 inhibits both cohesin and Sororin binding to chromatin.16 Although these observations suggest the requirement of cohesin for the association of Sororin with chromatin, it is apparent that cohesin alone is not sufficient to recruit Sororin to chromatids.

Figure 2. Role of Sororin in cohesin cycle. A model showing Sororin’s function in the maintenance and resolution of sister chromatid cohesion. (A) Cohesin is loaded to and associates with chromatin via Smc1-Smc3 hinge domain. (B) During DNA replication at S phase, cohesin passes thorough the replication fork, possibly by opening the linkage of N-terminus of Rad21 and Smc3 head domain. Once cohesin passes the replication fork, Smc3 is acetylated by Esco1/2. Sister chromatid cohesion is generated after two of the acetylated cohesin rings are dimerized by SA1/2 and other cohesin-associated proteins. (C) Cohesin-releasing activity of the releasin complex (Wapl-Pds5) is blocked after Wapl is displaced from the central binding site of Pds5 by Sororin. Now the sister chromatid cohesion is stable and can be maintained until the initiation of mitosis. (D) At prophase, Sororin is phosphorylated by Cdk1/cyclin B, which facilitates Plk1 to bind to Sororin and phosphorylates SA2. Phosphorylation of SA2 destabilizes cohesin complexes. Sororin dissociates from chromatin after it is further phosphorylated, which provides opportunity for Wapl to bind back to Pds5 and restores their cohesin-releasing activity. After cohesins are removed by Wapl-Pds5, the arms of the sister chromatid are resolved. (E) The released cohesins are regenerated by deacetylation of Smc3 and dephosphorylation of SA2, which can be reused in telophase.

Is DNA replication necessary for the recruitment of Sororin to chromatin? Although disruption of DNA replication by inhibitors, such as aphidicolin, actinomycin D, thymidine or p27 (inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinases), negatively affects Sororin association with chromatin, the association of cohesin with DNA remains unaffected.12,16 However, when recombinant Sororin is added to Sororin-depleted Xenopus extract at different DNA replication stages, Sororin binds to chromatin even after the completion of DNA replication.16 Therefore, Sororin binding to DNA is not dependent on DNA replication, per se, and the binding sites are available after completion of DNA replication. Because acetylation of Smc3 is coupled with DNA replication,48 disruption of DNA replication possibly inhibits Smc3 acetylation by Eco proteins, resulting indirectly in the reduction of Sororin recruitment to chromatin.

Is Eco protein required for the association of Sororin? Vertebrates have two Eco protein orthologs, Esco1 and Esco2,49 which acetylate vertebrate Smc3 at K102/103.6,12 Eco acetyltransferase is essential for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesin.4-6,49,50 When Esco1 and Esco2 are depleted using siRNA, or Esco2 is conditionally knocked out, Sororin association with chromatin also is reduced,12,51 implying that Eco proteins are required for the recruitment of Sororin to chromatin (Fig. 2B). Currently whether Sororin is acetylated by Eco proteins remains unknown. If the acetylation of Sororin by Eco proteins is essential, depletion of Eco protein would directly inhibit the recruitment of Sororin to chromatin. Alternatively, reduction of Sororin association with chromatin may be caused indirectly by Eco protein-mediated acetylation of Smc3.

The level of Sororin recruitment to chromatin is correlated with the amount of Esco2 during the DNA replication process. By delaying the addition of recombinant Esco2 to endogenous Esco2-depleted Xenopus extract, Sororin recruitment to chromatin can be reduced in a time- and dose-dependent manner.16 Esco2 can bind to chromatin when DNA replication is stalled by Aphidicolin, p27 or after completion of DNA replication. However, Sororin cannot be recruited to the chromatin with stalled or completed replication,16 suggesting that Eco proteins are not directly involved in the recruitment of Sororin.

Is acetylated Smc3 required for the recruitment of Sororin to chromatin? Several lines of evidence suggest that Sororin loading to chromatids relies on acetylated Smc3. First, Smc3 acetylation at K105 and K106 happens in the same time frame as does the association of Sororin with chromatin. Next, inhibition of DNA replication reduces both Smc3 acetylation and Sororin association with chromosome. Furthermore, inhibition of Smc3 acetylation by the depletion of Eco proteins results in the reduction of Sororin association with chromatin.12,16 Finally, ex vivo studies using HeLa cells indicated that Sororin can bind only to acetylated Smc3, supporting the notion that Smc3 acetylation by Eco proteins regulates Sororin recruitment to chromatin (Fig. 2B). However, acetylation of Smc3 and Sororin association with chromatin can be separated. Acetylation of Smc3 proceeds at least 30 min before Sororin association with chromatin is observed,12 suggesting that acetylation of Smc3 for the association of Sororin with chromatin is required but not sufficient. Moreover, if acetylation of K105 and K106 on Smc3 is necessary, mutations of these two residues should reduce or inhibit the recruitment of Sororin. Interestingly, however, mutations of K105 and K106 in Smc3 into glutamine, arginine or alanine residues (lysine into glutamine mimics acetylation and lysine changing into other residues mimics non-acetylation) enhance Sororin association with cohesin in both soluble and chromatin fractions.12 The results suggest that acetylation of Smc3 by Eco protein may be for the generation of cohesion rather than for the recruitment of Sororin. Any modification at K105 and K106 that causes a configuration switch of cohesin may facilitate Sororin binding.

In summary, it is clear that cohesin association with chromatin provides a base for Sororin binding and subsequent interaction with chromatin. Cohesin subunit Smc3 is required to be modified by Eco protein during DNA replication for the recruitment of Sororin to chromatin (Fig. 2A and B). However, all these factors are essential, but they are not sufficient for the recruitment of Sororin to chromatin.

Sororin Antagonizes Wapl

In both Xenopus egg extract system and HeLa cells, depletion of Sororin and Wapl has opposite effects on sister chromatid cohesion. The former causes chromosome separation, whereas the latter results in chromosome “over-cohesion.” The phenotype of sister chromatids in cells with the depletion of both Sororin and Wapl is similar to that in cells with Wapl depletion alone, suggesting that Sororin antagonizes Wapl and is dispensable when Wapl is absent.12

Both Sororin and Wapl proteins contain FGF motifs. The FGF motif is conserved in Sororin orthologs across different taxa. Depletion of Pds5 from Xenopus egg extracts greatly reduces Sororin association with chromatin, and mutation of FGF motif on Sororin reduces Sororin-Pds5 interaction,12 indicating that Sororin interacts with Pds5 via its FGF motif. Three FGF motifs have been identified in the N terminus of vertebrate Wapl. The first FGF motif primarily interacts with SA1 and Rad21, and the second and third FGF motifs modulate the interaction between Wapl and Pds5.17 Because both Sororin and Wapl interact with Pds5 via their FGF motifs and Sororin and Wapl have opposite effects on sister chromatid cohesion, the implication is that Sororin and Wapl compete with each other in binding to Pds5 (Fig. 2C). This notion is supported by the observation that Wapl is displaced from Pds5 when Sororin is incubated with Pds5-Wapl heterodimer without the presence of chromatin and Sororin with mutations in the FGF motif is less efficient in displacing Wapl. However, when recombinant Sororin was added to Xenopus egg extracts containing chromatin, rather than being decreased, the level of Wapl on chromatin increased,12 suggesting that Sororin may play a role in stabilizing Pds5-Wapl and cohesin, rather than displacing Wapl from cohesin. It has also been suggested that Sororin interaction with Pds5 may result in the topology switch of the cohesion-associated proteins, which prevents Wapl dissociating from cohesin.12 In addition to binding to Pds5, Wapl may also interact with chromatin, because the behavior of Wapl is different in Xenopus egg extract with chromatin from that without chromatin. Therefore, the alternative hypothesis is that Sororin bridges the Pds5-Wapl and cohesin by interacting with Pds5 via its FGF motif and with cohesin via its C terminus (Fig. 2C). It has also been suggested that Sororin-mediated antagonization of Wapl is regulated by the cell cycle. Recombinant Sororin can displace Wapl from Pds5-Wapl heterodimer in Xenopus interphase egg extract but not the mitotic egg extract. However, when a λ-protein phosphatase is added to Xenopus mitotic egg extract, the ability of Sororin to displace Wapl from Pds5-Wapl heterodimer is restored,12 suggesting that phosphorylation of Sororin prevents the displacement of Wapl from Pds5-Wapl heterodimer.

Sororin Regulates the Resolution of Sister Chromatid Cohesion

Cohesins in vertebrate cells dissociate from the sister chromatids in two steps: prophase and anaphase.18 The majority of cohesins on chromosomal arms dissociate during prophase and prometaphase in a non-proteolytic phosphorylation-dependent manner.18,25,52,53 The centromeric cohesins and the leftover cohesins on chromosomal arms dissociate from chromosomes after cohesin protease Separase cleaves the Rad21 subunit.18,54-56 However, removal of arm cohesins may also require Separase, since ablation of Separase reduces resolution of arm cohesion in prophase/prometaphase.56,57 Plk1 is required for the non-proteolytic cohesin dissociation in prophase step.54,55,58-60 Subsequent studies indicated that the phosphorylation of SA2 is essential for the dissociation of cohesin during prophase.58 Although SA2 phosphorylation can be catalyzed by Plk1 in vitro and in Xenopus egg extracts,60 the mechanism of SA2 phosphorylation remains unclear.

Plk1 contains a catalytic domain in its N terminus and two polo-box motifs in its C terminus. The two polo-box motifs form a polo-box domain (PBD), which is responsible for localizing the catalytic domain to the vicinity of its substrate by binding to a motif on the substrate itself or a docking protein.61-63 The consensus motif to which PBD binds is S(pS/pT)(P/X), where pS is phosphoserine, and pT is phosphothreonine.64 Although there are 17 S(ST)X motifs on SA2, no main PBD binding motif S(S/T)P is found. It is, therefore, possible that PBD does not bind to SA2 and instead binds to a docking protein to bring the catalytic domain to phosphorylate SA2.

A candidate protein that serves as the docking protein for SA2 to mediate Plk1 phosphorylation is Sororin. The ST159P motif in Sororin is conserved across vertebrates and is a Cdk1/cyclin B phosphorylation site.20 Plk1’s PBD binds to ST159P motif after T159 is phosphorylated by Cdk1/cyclin B in the early mitosis (Fig. 2D). When the threonine is mutated into alanine (T159A), the interaction of Sororin and Plk1 is prevented, and the resolution of chromosome arm cohesion is blocked.20 This phenotype is similar to that in cells expressing the nonphosphorylatable SA2 mutant,58 suggesting that PBD interacts with Sororin to bring the Plk1 catalytic domain to phosphorylate SA2, which is required for the dissociation of the arm cohesin.

Phosphorylation of Sororin in early mitosis not only helps to phosphorylate cohesin, but also destabilizes itself, resulting in its dissociation from chromatin. There are many potential phosphorylation sites on Sororin.20 Which site(s) must be phosphorylated in order for Sororin to dissociate from chromatin remains unknown. Also unclear is which kinase(s) phosphorylates Sororin after Plk1 modifies SA2. It is possible that Plk1 phosphorylates Sororin after SA2 phosphorylation to catalyze Sororin dissociation from chromatids (Fig. 2D). Dissociation of Sororin from chromatin facilitates Wapl binding back to Pds5, which then restores the cohesin-releasing activity to promote the removal of chromosomal arm cohesion (Fig. 2D and E).

Sororin and DNA Damage Repair

Cohesin is recruited to the sites of DNA double-strand break (DSB). Establishment of sister chromatid cohesion by cohesin is required for DSB repair in G2 in budding yeast65 and vertebrates.40,66 Because Sororin is essential for sister chromatid cohesion in G2 in vertebrates, Sororin may play a supporting role in DNA DSB repair. Indeed, DNA DSBs cannot be repaired when Sororin is depleted from cells, a phenotype reminiscent of Rad21 depletion. When Sororin-depleted cells were forced into mitosis by disabling the checkpoint with caffeine treatment, chromosomal fragments were observed in the chromosome metaphase spread.40,44 In DNA DSB repair, cohesin not only provides sister chromatid cohesion, but also is required for the activation of G2/M checkpoint. When Scc1 or Smc3 is depleted using siRNA and DNA, DSB is induced using etoposide or γ-irradiation at G2, cells can enter mitosis without DNA damage repair, suggesting that G2/M checkpoint is inactivated. However, Sororin involvement in DNA DSB repair only helps to establish or maintain sister chromatid cohesion but not in activating G2/M checkpoint.40

Sororin and Cancer

The role of Sororin in human cancer has not been fully investigated and our current understating of the role of Sororin in tumorigenesis is limited to only one report. According to this study, Sororin gene CDCA5 is overexpressed in the majority of lung cancers at both transcriptional and protein levels. Immunohistochemical analysis of 262 non-small cell lung cancer samples shows that more than 70% of these cases are Sororin-positive, and Sororin positivity is significantly associated with poor prognosis (p < 0.05).39

In ex vivo tissue culture models, overexpression of Sororin increases cell growth. In contrast, depletion of Sororin using siRNA significantly reduces the growth of two lung cancer cell lines, A459 and LC319.39 It is not only the protein level but also the specific modification that stimulate cell growth. As indicated above, ERK can phosphorylate Sororin at S209. When the serine residue is switched into glutamic acid that can mimic phosphorylation, cells expressing Sororin S209E mutant grow significantly faster than those expressing wild-type Sororin.39 When a Sororin peptide containing ERK phosphorylation site at Ser209 is introduced into cells, the growth of lung cancer cells that overexpress Sororin are inhibited, with no apparent effect on the growth of normal Sororin-expressing cells,39 suggesting that Sororin phosphorylation by ERK is important for cellular proliferation. Further studies are required to define the Sororin function in tumorigenesis and to test Sororin as a potential drug target particularly in cohesion-compromised tumors.

The Function of Sororin in Cohesin Cycle

Several cohesin models have been proposed to account for the sister chromatid cohesion.1,67-70 Here we use the handcuff model71,72 to summarize the role of Sororin in the maintenance and resolution of sister chromatid cohesion (Fig. 2). Cohesins are loaded before the S phase occurs (Fig. 2A), and Sororin is expressed during the S phase. Cohesin preoccupancy on chromatin is required but not sufficient for Sororin to associate with chromatids. After Smc3 is acetylated by Eco proteins during DNA replication, sister chromatid cohesion is generated by locking the N terminus of Rad21 to the acetylated Smc3 head, and the two cohesin rings with anti-parallel Rad21 molecules that brace each sister chromatid are linked by SA1/2, Pds5 and/ or other cohesin-associated proteins (Fig. 2B). However, this complex is not stable, because binding of Wapl to Pds5 via FGF motif can remove cohesins from sister chromatids. After Sororin binds to Smc3-acetylated cohesin, the cohesin-releasing function of Wapl-Pds5 can be antagonized by Sororin competing with Wapl in binding to Pds5. Sororin associates with cohesin via its C terminus and binds to Pds5 via its FGF motif. Once Sororin binds to the same site on Pds5 where Wapl binds, the cohesin-releasing activity of the releasin complex (Wapl-Pds5) is blocked, and sister chromatid cohesion is maintained from S phase to early mitosis (Fig. 2C). When the cell cycle enters mitosis, the ST159P motif of Sororin is phosphorylated by Cdk1/cyclin B (Fig. 2D). The PBD of Plk1 binds to SpT159P, and the catalytic domain of Plk1 phosphorylates SA2. Upon completion of the SA2 phosphorylation, Sororin is further phosphorylated by kinases such as Plk1 and/or other yet to be determined kinases, which results in the dissociation of Sororin from chromatin. The released Sororin is ubiquitinated by APCcdh1 and degraded by proteasome (Fig. 2D). Once the central binding site on Pds5 is vacated by Sororin, Wapl binds to this site to form a releasin complex that has cohesin-releasing activity and removes the SA2-phosphorylated cohesins from chromosome arms (Fig. 2D). The released cohesins can be regenerated via the deacetylation of Smc3 by Hos1,48,73,74 and dephosphorylation of SA2 by a yet to be identified phosphatase (Fig. 2E). The regenerated cohesin can associate with chromatin at telophase and start a new cohesin cycle.

Concluding Remark

Although Sororin plays an important role in the resolution of sister chromatid arm cohesion in prophase, it is unclear if Sororin functions in the removal of centromeric cohesin that is mediated by Separase. Our data show that Sororin interacts with Separase,75 suggesting Sororin might be involved in the Separase-mediated removal of cohesins. Recent studies indicate that the machinery of sister chromatid cohesion and separation, including Rad21, Smc1, Smc3, Sgo1, Plk1 and Separase, are not only required for the faithful passage of genetic material into daughter cells, but also in the engagement and disengagement of mother-daughter centrioles in centrosomes.23,26,30,31,43 Sororin has also been reported to localize in centrosomes.20 However, its role in the centrosome cycle is yet to be defined. It would be interesting to investigate if Sororin participates in the duplication of centrosomes. In addition to its canonical function in sister chromatid cohesion and separation, cohesin and its associating-proteins are major players in gene transcription and development.76-78 Therefore, Sororin’s role in gene expression would be an area of great interest. Furthermore, Sororin’s role in DNA replication is also an emerging area of research. Considering the involvement of Sororin in a wide range of cellular processes, it would not be surprising to find, in the near future, Sororin malfunction as the cause of diseases like cancer and Sororin as a potential target for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by award Numbers 1RO1 CA109478 and 1RO1 CA109330 from the National Cancer Institute and 2008 Virginia and L.E. Simmons Family Foundation Collaborative research award to D. Pati.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/20241

References

- 1.Nasmyth K. Cohesin: a catenase with separate entry and exit gates? Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1170–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillespie PJ, Hirano T. Scc2 couples replication licensing to sister chromatid cohesion in Xenopus egg extracts. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi TS, Yiu P, Chou MF, Gygi S, Walter JC. Recruitment of Xenopus Scc2 and cohesin to chromatin requires the pre-replication complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:991–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rolef Ben-Shahar T, Heeger S, Lehane C, East P, Flynn H, Skehel M, et al. Eco1-dependent cohesin acetylation during establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 2008;321:563–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1157774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unal E, Heidinger-Pauli JM, Kim W, Guacci V, Onn I, Gygi SP, et al. A molecular determinant for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 2008;321:566–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1157880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Shi X, Li Y, Kim BJ, Jia J, Huang Z, et al. Acetylation of Smc3 by Eco1 is required for S phase sister chromatid cohesion in both human and yeast. Mol Cell. 2008;31:143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandhi R, Gillespie PJ, Hirano T. Human Wapl is a cohesin-binding protein that promotes sister-chromatid resolution in mitotic prophase. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2406–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kueng S, Hegemann B, Peters BH, Lipp JJ, Schleiffer A, Mechtler K, et al. Wapl controls the dynamic association of cohesin with chromatin. Cell. 2006;127:955–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rankin S, Ayad NG, Kirschner MW. Sororin, a substrate of the anaphase-promoting complex, is required for sister chromatid cohesion in vertebrates. Mol Cell. 2005;18:185–200. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker MG. Drug target discovery by gene expression analysis: cell cycle genes. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2001;1:73–83. doi: 10.2174/1568009013334241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castro A, Bernis C, Vigneron S, Labbé JC, Lorca T. The anaphase-promoting complex: a key factor in the regulation of cell cycle. Oncogene. 2005;24:314–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishiyama T, Ladurner R, Schmitz J, Kreidl E, Schleiffer A, Bhaskara V, et al. Sororin mediates sister chromatid cohesion by antagonizing Wapl. Cell. 2010;143:737–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prokopenko SN, He Y, Lu Y, Bellen HJ. Mutations affecting the development of the peripheral nervous system in Drosophila: a molecular screen for novel proteins. Genetics. 2000;156:1691–715. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.4.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goshima G, Wollman R, Goodwin SS, Zhang N, Scholey JM, Vale RD, et al. Genes required for mitotic spindle assembly in Drosophila S2 cells. Science. 2007;316:417–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1141314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Somma MP, Ceprani F, Bucciarelli E, Naim V, De Arcangelis V, Piergentili R, et al. Identification of Drosophila mitotic genes by combining co-expression analysis and RNA interference. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lafont AL, Song J, Rankin S. Sororin cooperates with the acetyltransferase Eco2 to ensure DNA replication-dependent sister chromatid cohesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20364–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011069107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shintomi K, Hirano T. Releasing cohesin from chromosome arms in early mitosis: opposing actions of Wapl-Pds5 and Sgo1. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2224–36. doi: 10.1101/gad.1844309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waizenegger IC, Hauf S, Meinke A, Peters JM. Two distinct pathways remove mammalian cohesin from chromosome arms in prophase and from centromeres in anaphase. Cell. 2000;103:399–410. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00132-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciosk R, Zachariae W, Michaelis C, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Nasmyth K. An ESP1/PDS1 complex regulates loss of sister chromatid cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition in yeast. Cell. 1998;93:1067–76. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang N, Panigrahi AK, Mao Q, Pati D. Interaction of Sororin protein with polo-like kinase 1 mediates resolution of chromosomal arm cohesion. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:41826–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.305888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreier MR, Bekier ME, 2nd, Taylor WR. Regulation of sororin by Cdk1-mediated phosphorylation. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:2976–87. doi: 10.1242/jcs.085431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gregson HC, Schmiesing JA, Kim JS, Kobayashi T, Zhou S, Yokomori K. A potential role for human cohesin in mitotic spindle aster assembly. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47575–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guan J, Ekwurtzel E, Kvist U, Yuan L. Cohesin protein SMC1 is a centrosomal protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:761–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong X, Ball AR, Jr., Sonoda E, Feng J, Takeda S, Fukagawa T, et al. Cohesin associates with spindle poles in a mitosis-specific manner and functions in spindle assembly in vertebrate cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1289–301. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-04-0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warren WD, Steffensen S, Lin E, Coelho P, Loupart M, Cobbe N, et al. The Drosophila RAD21 cohesin persists at the centromere region in mitosis. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1463–6. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00806-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giménez-Abián JF, Díaz-Martínez LA, Beauchene NA, Hsu WS, Tsai HJ, Clarke DJ. Determinants of Rad21 localization at the centrosome in human cells. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1759–63. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.9.11523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beauchene NA, Díaz-Martínez LA, Furniss K, Hsu WS, Tsai HJ, Chamberlain C, et al. Rad21 is required for centrosome integrity in human cells independently of its role in chromosome cohesion. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1774–80. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.9.11524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong RW, Blobel G. Cohesin subunit SMC1 associates with mitotic microtubules at the spindle pole. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15441–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807660105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong RW. Interaction between Rae1 and cohesin subunit SMC1 is required for proper spindle formation. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:198–200. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.1.10431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamura A, Arai H, Fujita N. Centrosomal Aki1 and cohesin function in separase-regulated centriole disengagement. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:607–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schöckel L, Möckel M, Mayer B, Boos D, Stemmann O. Cleavage of cohesin rings coordinates the separation of centrioles and chromatids. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:966–72. doi: 10.1038/ncb2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Díaz-Martínez LA, Giménez-Abián JF, Clarke DJ. Regulation of centromeric cohesion by sororin independently of the APC/C. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:714–24. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.6.3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Hoof D, Muñoz J, Braam SR, Pinkse MW, Linding R, Heck AJ, et al. Phosphorylation dynamics during early differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:214–26. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen RQ, Yang QK, Lu BW, Yi W, Cantin G, Chen YL, et al. CDC25B mediates rapamycin-induced oncogenic responses in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2663–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dephoure N, Zhou C, Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Bakalarski CE, Elledge SJ, et al. A quantitative atlas of mitotic phosphorylation. 2008;105:10762–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805139105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cantin GT, Yi W, Lu B, Park SK, Xu T, Lee JD, et al. Combining protein-based IMAC, peptide-based IMAC, and MudPIT for efficient phosphoproteomic analysis. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1346–51. doi: 10.1021/pr0705441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beausoleil SA, Villén J, Gerber SA, Rush J, Gygi SP. A probability-based approach for high-throughput protein phosphorylation analysis and site localization. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1285–92. doi: 10.1038/nbt1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, et al. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen MH, Koinuma J, Ueda K, Ito T, Tsuchiya E, Nakamura Y, et al. Phosphorylation and activation of cell division cycle associated 5 by mitogen-activated protein kinase play a crucial role in human lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5337–47. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watrin E, Peters JM. The cohesin complex is required for the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2009;28:2625–35. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ubersax JA, Woodbury EL, Quang PN, Paraz M, Blethrow JD, Shah K, et al. Targets of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk1. Nature. 2003;425:859–64. doi: 10.1038/nature02062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudner AD, Hardwick KG, Murray AW. Cdc28 activates exit from mitosis in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1361–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsou MF, Wang WJ, George KA, Uryu K, Stearns T, Jallepalli PV. Polo kinase and separase regulate the mitotic licensing of centriole duplication in human cells. Dev Cell. 2009;17:344–54. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmitz J, Watrin E, Lénárt P, Mechtler K, Peters JM. Sororin is required for stable binding of cohesin to chromatin and for sister chromatid cohesion in interphase. Curr Biol. 2007;17:630–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu FM, Nguyen JV, Rankin S. A conserved motif at the C terminus of sororin is required for sister chromatid cohesion. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:3579–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.196758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li A, Blow JJ. Cdt1 downregulation by proteolysis and geminin inhibition prevents DNA re-replication in Xenopus. EMBO J. 2005;24:395–404. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGarry TJ, Kirschner MW. Geminin, an inhibitor of DNA replication, is degraded during mitosis. Cell. 1998;93:1043–53. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81209-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beckouët F, Hu B, Roig MB, Sutani T, Komata M, Uluocak P, et al. An Smc3 acetylation cycle is essential for establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Mol Cell. 2010;39:689–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hou F, Zou H. Two human orthologues of Eco1/Ctf7 acetyltransferases are both required for proper sister-chromatid cohesion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3908–18. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tóth A, Ciosk R, Uhlmann F, Galova M, Schleiffer A, Nasmyth K. Yeast cohesin complex requires a conserved protein, Eco1p(Ctf7), to establish cohesion between sister chromatids during DNA replication. Genes Dev. 1999;13:320–33. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whelan G, Kreidl E, Wutz G, Egner A, Peters JM, Eichele G. Cohesin acetyltransferase Esco2 is a cell viability factor and is required for cohesion in pericentric heterochromatin. EMBO J. 2012;31:71–82. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Losada A, Hirano M, Hirano T. Identification of Xenopus SMC protein complexes required for sister chromatid cohesion. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1986–97. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Losada A, Yokochi T, Kobayashi R, Hirano T. Identification and characterization of SA/Scc3p subunits in the Xenopus and human cohesin complexes. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:405–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giménez-Abián JF, Sumara I, Hirota T, Hauf S, Gerlich D, de la Torre C, et al. Regulation of sister chromatid cohesion between chromosome arms. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hauf S, Waizenegger IC, Peters JM. Cohesin cleavage by separase required for anaphase and cytokinesis in human cells. Science. 2001;293:1320–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1061376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakajima M, Kumada K, Hatakeyama K, Noda T, Peters JM, Hirota T. The complete removal of cohesin from chromosome arms depends on separase. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4188–96. doi: 10.1242/jcs.011528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giménez-Abián JF, Díaz-Martínez LA, Waizenegger IC, Giménez-Martín G, Clarke DJ. Separase is required at multiple pre-anaphase cell cycle stages in human cells. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1576–84. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.11.2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hauf S, Roitinger E, Koch B, Dittrich CM, Mechtler K, Peters JM. Dissociation of cohesin from chromosome arms and loss of arm cohesion during early mitosis depends on phosphorylation of SA2. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e69. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Losada A, Hirano M, Hirano T. Cohesin release is required for sister chromatid resolution, but not for condensin-mediated compaction, at the onset of mitosis. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3004–16. doi: 10.1101/gad.249202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sumara I, Vorlaufer E, Stukenberg PT, Kelm O, Redemann N, Nigg EA, et al. The dissociation of cohesin from chromosomes in prophase is regulated by Polo-like kinase. Mol Cell. 2002;9:515–25. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00473-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Elia AE, Rellos P, Haire LF, Chao JW, Ivins FJ, Hoepker K, et al. The molecular basis for phosphodependent substrate targeting and regulation of Plks by the Polo-box domain. Cell. 2003;115:83–95. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00725-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lowery DM, Lim D, Yaffe MB. Structure and function of Polo-like kinases. Oncogene. 2005;24:248–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lowery DM, Mohammad DH, Elia AE, Yaffe MB. The Polo-box domain: a molecular integrator of mitotic kinase cascades and Polo-like kinase function. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:128–31. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.2.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elia AE, Cantley LC, Yaffe MB. Proteomic screen finds pSer/pThr-binding domain localizing Plk1 to mitotic substrates. Science. 2003;299:1228–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1079079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sjögren C, Nasmyth K. Sister chromatid cohesion is required for postreplicative double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Biol. 2001;11:991–5. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watrin E, Peters JM. Cohesin and DNA damage repair. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:2687–93. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Campbell JL, Cohen-Fix O. Chromosome cohesion: ring around the sisters? Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:492–5. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gruber S, Haering CH, Nasmyth K. Chromosomal cohesin forms a ring. Cell. 2003;112:765–77. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huang CE, Milutinovich M, Koshland D. Rings, bracelet or snaps: fashionable alternatives for Smc complexes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:537–42. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Skibbens RV, Maradeo M, Eastman L. Fork it over: the cohesion establishment factor Ctf7p and DNA replication. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2471–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.011999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang N, Kuznetsov SG, Sharan SK, Li K, Rao PH, Pati D. A handcuff model for the cohesin complex. 2008;183:1019, 31. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang N, Pati D. Handcuff for sisters: a new model for sister chromatid cohesion. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:399–402. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.3.7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Borges V, Lehane C, Lopez-Serra L, Flynn H, Skehel M, Rolef Ben-Shahar T, et al. Hos1 deacetylates Smc3 to close the cohesin acetylation cycle. Mol Cell. 2010;39:677–88. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xiong B, Lu S, Gerton JL. Hos1 is a lysine deacetylase for the Smc3 subunit of cohesin. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1660–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang N, Prahan SX, Jean B, Rao PH, Pati D. A novel separase interacting protein—Insep5 functions in sister chromatid cohesion and separation. FASEB J. 2007;21:813.1. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Remeseiro S, Cuadrado A, Carretero M, Martínez P, Drosopoulos WC, Cañamero M, et al. Cohesin-SA1 deficiency drives aneuploidy and tumourigenesis in mice due to impaired replication of telomeres. EMBO J. 2012 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fay A, Misulovin Z, Li J, Schaaf CA, Gause M, Gilmour DS, et al. Cohesin selectively binds and regulates genes with paused RNA polymerase. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1624–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rhodes JM, McEwan M, Horsfield JA. Gene regulation by cohesin in cancer: is the ring an unexpected party to proliferation? Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:1587–607. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]