Abstract

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) occur in the context of a highly organized chromatin environment and are, thus, a significant threat to the epigenomic integrity of eukaryotic cells. Changes in break-proximal chromatin structure are thought to be a prerequisite for efficient DNA repair and may help protect the structural integrity of the nucleus. Unlike most bona fide DNA repair factors, chromatin influences the repair process at several levels: the existing chromatin context at the site of damage directly affects the access and kinetics of the repair machinery; DSB induced chromatin modifications influence the choice of repair factors, thereby modulating repair outcome; lastly, DNA damage can have a significant impact on chromatin beyond the site of damage. We will discuss recent findings that highlight both the complexity and importance of dynamic and tightly orchestrated chromatin reorganization to ensure efficient DSB repair and nuclear integrity.

Keywords: Chromatin, DNA repair, nuclear reorganization, histone modification

1. Introduction

Eukaryotic DNA is highly organized in nuclear space, ensuring proper gene expression and structural integrity of the genome. To achieve this three-dimensional organization, DNA is wrapped around nucleosomes, which are then packaged into chromatin fibers to varying degrees of compaction. Nucleosomes consist of an octameric histone protein complex, which in its basic form includes two molecules of each core histone, H2A, H2B, H3 and H4. Nucleosome packaging and positioning can be modulated by the post-translational modification of histones as well as through incorporation of histone variants, such as the H2A variants macro-H2A, H2AX and H2AZ. The ensuing alterations in chromatin structure can affect a variety of nuclear processes including transcription, DNA repair, chromosome segregation and gene silencing [1, 2].

Chromatinized DNA in all its structural complexity is often referred to as the “epigenome” and its integrity is highly susceptible to both exogenous and endogenous sources of damage. Exogenous, or environmental damaging agents include UV light and other types of radiation as well as genotoxic carcinogens often used in cancer chemotherapy. The most frequent cell-intrinsic sources of genotoxic stress include free oxygen radicals as a result of increased cellular respiration, collapsed DNA replication forks as a consequence of cell division and variable joining of V, D and J gene segments or class switch recombination during lymphocyte development [3]. Depending on the challenge, this can result in DNA base damage, single stranded DNA (ssDNA) breaks, interstrand crosslinking of DNA and DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). DSBs are particularly dangerous to cells as the failure to repair DSBs can cause cell death, and their aberrant repair can lead to gross chromosomal changes that may eventually promote tumorigenesis [3]. DSBs are, thus, among the most heavily investigated DNA lesions and it is becoming increasingly evident that their damaging effect is not limited to DNA but extends to and is influenced by the surrounding chromatin environment [4].

DSB repair generally occurs through one of two major pathways; nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ), which is by nature error-prone, or homologous recombination (HR), which restores the original DNA sequence using undamaged template DNA, generally the sister chromatid. NHEJ repairs DSBs in all phases of the cell cycle, while HR is dependent on the presence of a homologous DNA template and, thus, generally limited to S phase and G2 [3]. The molecular identity of these repair pathways has been outlined over the past decades using biochemical, genetic and molecular methods, and is well documented in other reviews [3–5]. In brief, DSBs activate a complex cellular DNA-damage response (DDR) involving a signal transduction pathway that senses the break and sets in motion a highly orchestrated series of events resulting in repair, cell cycle arrest or apotosis, depending on the damage load and cell cycle state. The DDR is often initiated by the rapid accumulation of the MRN (MRE11–RAD50–NBS1) complex at the break site, which is in turn crucial for the recruitment and activation of the central DDR signaling kinase Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM). Amongst other targets, ATM then phosphorylates a conserved residue of the histone variant H2AX (S139 in humans, referred to as γ-H2AX, or γ-H2A in yeast and γ-H2Av in Drosophila melanogaster), providing a high-affinity binding site for MDC1, which in turn orchestrates the recruitment of a variety of functionally distinct downstream DNA break-associated repair factors [6]. It is of note that lower eukaryotes lack MDC1 homologs and phosphorylated H2A or H2Av are instead able to assemble downstream effectors directly. H2AX phosphorylation also promotes further MRN recruitment, thereby amplifying the damage signal. As a consequence, a single DSB can result in H2AX phosphorylation up to one megabase from the break site, which can be visualized as a discernible nuclear focus using immunofluorescent microscopy [7]. Accumulating evidence suggests that the assembly of such repair foci is regulated both temporally and spatially in the context of the surrounding chromatin [5, 8]. Consistent with this notion, a vast number of enzymatic activities that chemically or physically modify chromatin structures in a reversible manner have been linked to DSB repair. These modifications include but are not limited to phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation and ubiquitylation, and the implications of DSB-induced chromatin reorganization are only beginning to be understood [9]. In this review, we will discuss three distinct but functionally related aspects of DNA repair in the context of chromatin: (i) the role of chromatin in the DSB repair process itself, (ii) the impact of the preexisting chromatin environment on DNA repair and (iii) the effect of DSB repair on nuclear organization beyond the sites of damage.

2. Chromatin alterations as a consequence of DSBs

DSB-induced alterations in chromatin structure range from relaxation of chromatin fibers and the associated repair factor recruitment to transcriptional repression in the vicinity of DSBs, emphasizing the complex role of chromatin during the repair process. Recent advances in our understanding of DSB-induced chromatin reorganization are highlighted in the following.

2. 1 Nucleosome remodeling in DNA repair

As a first step in the repair of chromatinized DNA, damage sensors and repair factors have to gain access to the site of damage. DNA damage-induced chromatin remodeling at the nucleosome level has been proposed as early as 1978 by Smerdon and Lieberman [10], and technological advances as well as a thorough molecular characterization of chromatin have since greatly improved our understanding of this pioneering observation. Using electron microscopy, it has been demonstrated that DSBs lead to a rapid, ATP-dependent, local chromatin de-condensation in the absence of ATM activation, supporting the notion that changes in chromatin architecture are involved in the initiation of the DDR upstream of ATM signaling [11, 12]. Consistent with this observation, a recent report shows that activation of ATM is dependent on the nucleosome binding protein HMGN1, which modulates the interaction of ATM with chromatin both before and after DSB formation [13]. Once ATM is activated, DSB-surrounding chromatin is further altered by ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes, which remove histones or alter their conformation and nucleosome positioning at DSB sites [8, 14]. Prominent examples are the INO80 and SWR1 remodeling complexes, which function cooperatively with their histone substrates γ-H2AX and H2AZ to regulate access of early repair factors such as the MRN complex [15]. Perhaps surprisingly, components of the nucleosome-remodeling and histone deacetylase (NuRD) complex, including MTA2, CHD4, HDAC1 and HDAC2, were also found to be recruited to DSBs where they promote repair and checkpoint activation [16–21]. NuRD function is often associated with transcriptional silencing [22] and association of NuRD components with DSB sites has been correlated with depletion of RNA polymerase II [23]. Consistent with the latter, it was recently reported that a spatially defined DSB can result in suppression of RNA Polymerase (Pol) II activation and transcription-coupled locus decondensation (see also 2.4.). However, a role for chromatin remodeling in this process remains to be determined. At this point, little is known about these seemingly opposing roles of chromatin reorganization in the repair process and it will be interesting to determine how accessibility and transcriptional silencing are orchestrated and interpreted at DSB sites.

2. 2. Covalent histone modifications in DNA repair

In addition to nucleosome remodeling complexes, DNA repair involves an extensive set of histone modifications that either directly contribute to chromatin reorganization or provide a docking site for regulatory proteins and downstream repair factors [9]. Arguably the most prominent DNA-damage induced histone modification is the poshporylation of H2AX (see above). For a detailed description of γ-H2AX function in DSB repair, we refer the reader to a number of excellent recent reviews [3, 4, 6]. Several other histone modifications, including acetylation, methylation, and ubiquitylation of core histones, have now been linked to DNA repair, many of which function as mediators of repair factor recruitment and/or retention much like γ-H2AX [9]. Combinatorial histone modification at DSBs is highly reminiscent of the regulation of transcription by chromatin, where distinct histone modifications act sequentially or in combination as a landing platform for transcription factors and other regulatory complexes, a phenomenon often referred to as “histone code” [24]. In the following, we will focus on a subset of histone marks that highlight the functional diversity of chromatin modifications in DSB repair.

A well-studied DDR-related histone modifier is the Tip60 acetyltransferase. Tip60 can acetylate both histones and ATM and loss of Tip60 function leads to defective DNA repair and increased cancer risk [25]. Tip60-mediated acetylation of histone H4 was shown to promote chromatin decondensation and the accumulation of repair factors at the DSB site [25]. Tip60 recruitment is further enhanced by the MRN complex, which is required to activate its acetyltransferase activity [26]. Interestingly, histone acetylation is not only involved in rendering chromatin accessible for DSB repair factors, but also in the ensuing chromatin re-assembly. Acetylation of lysine 56 (K56) on newly synthesized histone H3 molecules was shown to correlate with the induction of DSBs during DNA replication and precedes histone H3 incorporation into nucleosomes. Accordingly, defects in H3K56 acetylation resulted in increased sensitivity to genotoxic stress in yeast [27]. DSB-associated H3K56 acetylation is dependent on the histone chaperone ASF1 and is required for CAF1-assisted nucleosome incorporation to re-establish functional chromatin following its break-proximal disruption [28]. This process is conserved from yeast to human cells and depends on tightly regulated acetylation and deacetylation of H3K56, which can be mediated by CBP/p300 and the sirtuin deacetylaes SIRT1, SIRT2 and SIRT6 respectively [28–31]. Interestingly, the class I histone deacetylases and NuRD components HDAC1 and HDAC2 were recently found to promote DSB repair by deacetylating H3K56 at DSB sites, which may in part explain the role of NuRD in DSB repair (see 2.1.) [20].

Apart from structural changes, histone modifications can direct and modulate the recruitment of repair factors, much like it has been observed for transcription factors. A prominent example is the K63-linked poly-ubiquitylation of histone H2A (Ub-H2A) observed at ionizing radiation-induced foci (IRIF). DSB-induced (poly-)ubiquitylation is dependent on γ-H2AX/MDC1-mediated recruitment of the RING-finger ubiquitin ligases RNF8 and RNF168, and facilitates the accumulation of the downstream repair factors BRCA1 and 53BP1 at sites of damage [32–35]. Interestingly, neither BRCA1 nor 53BP1 possess ubiquitin interacting motifs (UIMs). In the case of BRCA1, recruitment to K63-linked Ub is mediated by the UIM containing RAP80 protein, which interacts with the BRCT domain of BRCA1 through ABRA1 [36–38]. How K63-linked Ub mediates 53BP1 accumulation, on the other hand, is still unclear.

In addition to K63-linked polyubiquitylation, monoubiquitylation of K119 on H2A by RNF8/RNF168 (K119 Ub-H2A) as well as K120 on H2B by RNF20/RNF40 (K120 H2B-Ub) have recently been implicated in DSB repair downstream of ATM [39–41]. Interestingly, monoubiquitylated H2A and H2B have seemingly opposing functions in a non-damage context, where K119 Ub-H2A has been correlated with transcriptional silencing via the polycomb group (PcG) repressive complex [42], and K120 H2B-Ub has been reported to facilitate transcript elongation via transcription-coupled chromatin reorganization and histone eviction [43]. Recent findings suggest that a similar distinction holds true for their function in DSB repair. DSB-induced K119 Ub-H2A was found to promote transcriptional repression near break sites (see 2.4.). Accordingly, several members of the PcG complex have been implicated in DSB repair [21, 41] and the PcG component BMI1 was shown to be required for DSB-induced ubiquitylation of H2A at K119 [44]. In contrast, K120 H2B-Ub was shown to promote DSB repair presumably by mediating chromatin accessibility, as defects in H2B mono-ubiquitylation can be partially restored by forced chromatin relaxation [39, 40]. Together, these observations suggest a complex role for ubiquitylation of histone H2 variants in both repair factor assembly and DSB-proximal chromatin reorganization that is dependent on the type of ubiquitylation as well as the H2 substrate.

In addition to ubiquitylation, modification of DSB-proximal factors by the small ubiquitin-related modifiers SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 has recently been implicated in DSB repair. SUMO accumulation at DSBs was found to promote the recruitment of 53BP1 and BRCA1 to DSB sites and is required for effective ubiquitin-adduct formation via RNF8/RNF168, suggesting a role upstream of ubiquitylation [45]. While the SUMO targets mediating repair factor recruitment remain to be determined [46], it is of note that SUMO modification of the histone variant H2AZ was shown to be involved in the structural relocation of a persisting DSB to the nuclear periphery [47], suggesting diverse roles for SUMO in repair factor assembly and break-proximal chromatin remodeling.

Finally, histone methylation is emerging to be a critical modulator of DSB repair. Like SUMO and H2A-Ub, di-methylation of histone H4 on lysine 20 (H4K20me2) has been shown to mediate the recruitment of 53BP1 [48, 49]. This process appears to be, at least in part, dependent on the histone methyltransferase MMSET (also known as NSD2 or WHSC1) [50], as downregulation of MMSET significantly decreased H4K20 methylation and the subsequent accumulation of 53BP1 at DSB sites. A similar role for 53BP1 recruitment has been reported for methylation of H3K79 by the methyltransferase DOT1L [51] and recruitment to both H3K79me2 and H4K20me2 was shown to require the methyl-lysine binding tandem tudor domain of 53BP1 [48, 49]. The complex regulation of 53BP1 recruitment by various histone modifications points to a central role for 53BP1 in DSB repair. Consistent with this notion, it was shown recently that 53BP1 affects repair pathway choice, a process that is especially apparent in the absence of the tumor suppressor BRCA1 [52, 53]. BRCA1 deficient cells show defects in HR and chromosomal rearrangements due to aberrant NHEJ. Deletion of 53BP1 in these cells restored HR and genomic stability by restoring access for HR components that are normally recruited by BRCA1-mediated 53BP1 displacement. In light of this finding, it is tempting to speculate that the choice between HR and NHEJ may be initiated or modulated at the level of histone modifications, possibly in a combinatorial manner.

2. 3. Histone variant dynamics in DNA repair

DSB-induced changes in the histone environment are not limited to histone modifications but can involve the recruitment and/or incorporation of histone variants into break-proximal nucleosomes. In yeast, the SWR1 complex replaces γ-H2A with the phosphorylation inert variant H2AZ [54], whereas the INO80 complex was proposed to be required for maintaining γ-H2A at unrepaired DSBs [54]. A similar histone exchange process was observed in Drosophila, where the Tip60 complex acetylates nucleosomal phospho-H2Av and replaces it with unmodified H2Av [55]. The human and Drosophila Tip60 complexes share many subunits with yeast INO80, SWR1, and NuA4 [15], suggesting that they may function as hybrid orthologs of the yeast complexes. It is tempting to speculate that this conserved exchange of histone variants may be involved in the restoration of break associated epigenetic information.

More recently, the macro domain containing histone variant macroH2A1.1 has been implicated in DNA repair [56]. Using a variety of biochemical assays, Ladurner and colleagues were able to show that the macrodomain of macroH2A1.1 but not that of the macroH2A1.2 splice variant or the macroH2A2 isoform, binds to both mono- and poly-ADP-ribose (PAR). PAR polymerase 1 (PARP1) mediated PARylation of histones and other DSB-proximal repair components plays an important role in DSB signaling, chromatin reorganization and repair factor recruitment [57]. Notably, the authors observed that ectopically expressed macroH2A1.1 is recruited to laser-generated DNA lesions, accompanied by the accumulation of linker histone H1, suggesting the formation of a compacted chromatin environment. However, while histone H1, macroH2A and PARP1 can independently promote compacted chromatin structures [58, 59], PARP1 activity was recently found to mediate exclusion of histone H1 at promoters [60]. Furthermore, PAR-mediated recruitment of mH2A1.1 does not appear to involve its incorporation into nucleosomes, and more work is needed to dissect the complex functional relationship between PAR, macroH2A1.1 and histone H1 at DSBs.

2. 4. DSBs and chromatin condensation

Although there is abundant evidence for chromatin relaxation during the initial phases of the repair process, many of the findings outlined above point to a role for repressive chromatin at sites of DNA breakage. In the following we will discuss several recent observations that underscore the functional relevance a repressive microenvironment could have for DSB repair. DNA lesions pose a major obstacle to DNA polymerase activity [3] and a long-standing question is whether the transcription machinery is also affected by the presence of DSBs. Kruhlak and colleagues demonstrated in 2007, that DSBs can inhibit RNA Polymerase I (PolI) transcription and thereby transiently shut down ribosomal gene expression [61]. This process is dependent on ATM and its downstream DDR mediators MDC1 and NBS1. However, this work did not determine if transcription is shut down specifically at the site of DNA damage, where it may be most critical. More recently, Greenberg and colleagues were able to address this question using a sophisticated genetic reporter, which allows the visualization of transcription near break sites at single cell resolution. The authors found that spatially defined DSB induction results in suppression of RNA PolII activity and abrogation of transcription-coupled chromatin decondensation, spreading across several kilobases of chromatin in cis to DSBs. Similar to the inhibition of RNA PolI, this process was ATM dependent [41]. It was further linked to ubiquitylation of histone H2A (see 2.2.), however, the mechanism by which H2A-Ub affects this process remains to be determined.

More direct evidence for DSB-induced chromatin compaction comes from the observation that heterochromatin protein HP1 variants accumulate at DSB sites [62]. Given that HP1-β has also been reported to dissociate from DSBs early in the DDR [64], a bimodal response has been proposed to explain the role of HP1 in DSB repair [65]. However, early HP1 dissociation was observed in only one of the studies [64], suggesting cell type- or lesion-specific differences in DDR signaling, and, hence, a more complex regulation of HP1-mediated DSB-proximal chromatin remodeling.

In addition to a possible role for silent chromatin marks in DSB repair, several recent observations suggest that DSB-proximal DNA can become hypermethylated at CpG islands in a DNMT1 methyltransferase-dependent manner, which in turn results in reduced expression of genes adjacent to DSBs [66–68]. DSB-induced DNA methylation further appears to be a heritable alteration and may, thereby, stably alter sites of (former) damage [68]. Consistent with this notion, it has been reported that DNA damage-mediated methylation of CpG promoter islands can contribute to aberrant silencing associated with cancer and aging [68, 69]. However, only a subset of cells undergoing DSB repair displays break-proximal CpG methylation and little is known about its regulation and functional relevance for the repair process. Recently, it was shown that depletion of the DNMT1 activator DMAP1 increases HR efficiency, suggesting that DSB-proximal DNA methylation may interfere with DSB repair although the molecular basis for this observation is unclear [67].

Additional clues for the possible functional relevance of a repressive chromatin environment in the DSB repair process have come from the recent observation that DNA breaks display positional stability within nuclear space [70]. Interestingly, a loss of local positional restrain in the absence of the NHEJ factor Ku80, which the authors implicated in positional stability, resulted in increased genomic instability and translocation to neighboring chromosomes. However, alterations in the DSB-proximal chromatin environment have not been analyzed in this study. Together, these observations suggest that compacted chromatin may serve to isolate repair foci, thereby preventing potentially hazardous encounters of the transcription machinery with DSBs as well as aberrant DSB repair and genomic translocations. The proposed DSB-proximal chromatin compaction is reminiscent of the encapsulation of damaged tissue observed during a wound-healing response (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Chromatin dynamics in DSB repair.

DSBs can occur in euchromatin (A, left panel) or heterochromatin (A, right panel). In both cases, phosphorylation of H2AX occurs soon after DSB induction and is followed by recruitment of MDC1 and downstream repair factors as well as histone modifiers (B). Heterochromatic lesions are not easily accessible to downstream repair factors such as the MRN complex. In yeast and flies, these lesions are, thus, protruded to the heterochromatic periphery by the SMC5/6 complex (B, right panel). Displacement of phosphorylated HP1 and KAP1 has also been reported as a means to make heterochromatic DNA lesions accessible. Removal of HP1 renders H3K9me3 accessible for Tip60 binding, which in turn acetylates histone H4 to promote chromatin relaxation. If the latter is also responsible for Tip60 recruitment in euchromatin remains to be determined. Once protruded, it is likely that repair of DSB-containing heterochromatic DNA follows the same principles as euchromatic repair (B, left panel). A large number of histone modifiers (HMs) and chromatin remodeling complexes as well as histone chaperones (e.g. ASF1) have been implicated in this process and are described in more detail in the text. Unlike heterochromatin, euchromatic chromatin is generally transcriptionally active and DSB repair is associated with pausing of RNA polymerase II (RNA PolII) in cis. (C) Recent work suggests that initial chromatin relaxation is followed by chromatin compaction, which is supported by the transient eviction of RNA PolII and the accumulation of HP1 at DSB sites. NuRD-mediated chromatin remodeling may be involved in chromatin compaction. It is unclear if compaction occurs during or after the religation of DSBs. Kinetic data support the former as numerous repair factors are retained at the DSB site for prolonged periods of time. Green arrows indicate addition of a component or modification, red arrows indicate removal.

2. 5. Replication stress and 53BP1 nuclear bodies

A rather specialized structural response to DNA lesions consistent with the idea of DSB site isolation has been reported recently by the Lukas and Jackson labs [71, 72]. Both groups found that DNA replication associated DNA lesions, which are generally found at genomic sites where replication fork progression is problematic, such as chromosomal fragile sites and repetitive DNA [73], are marked by persisting 53BP1 nuclear bodies in G1. These structures appear to be established in anaphase, where unresolved replication intermediates can remain connected via ultra-fine DNA bridges. Lukas and colleagues now show that such under-replicated fragile sites can be segregated in a BLM helicase dependent manner. The resulting lesions are then transmitted symmetrically to daughter cells, where they associate with 53BP1 [72]. The fate of 53BP1 nuclear bodies is at this point unclear. The authors propose that sequestration of unrepaired DSBs in specialized nuclear compartments may prohibit excessive processing of broken DNA ends, thereby limiting genomic aberrations at fragile DNA elements. Given the striking persistence of 53BP1 nuclear bodies throughout most of G1 and the requirement for a variety of histone modifications in the recruitment of 53BP1 (see 2.2.), it will be interesting to determine if and how chromatin alterations may be involved in the formation and resolution of these specialized, repair-associated structures.

Together, these findings demonstrate a central role for structural changes, generally involving the modification of chromatin components, in the orchestration of the DDR (Figure 1). While current research has mostly focused on chromatin modifications occurring early in the DDR, little is known about their relevance later in the response. Interestingly, 53BP1 and γ-H2AX can be detected hours after the initial lesion and it will be interesting to investigate if these marks are part of persisting alterations in the DSB-proximal chromatin microenvironment. To keep with the analogy of transcription, where chromatin can serve as a heritable mark for active or repressed genes, it may, similarly, serve to persistently mark sites of (repaired) DNA damage. The latter is particularly intriguing as asymmetric separation of damaged and undamaged DNA strand has been suggested in the context of stem cell division [74].

3. Influence of the pre-existing chromatin environment on DSB repair

Coordinated regulation of DNA repair and chromatin dynamics are required to ensure the maintenance of both genetic and epigenetic information. DNA repair in the context of chromatin represents a challenge not only in terms of accessibility to the lesion but also with regard to maintenance of (epi)genomic stability after the repair process is finished. Although surprisingly little is known about persisting chromatin changes or epigenetic restoration at DSB sites, our understanding of chromatin-context dependent initiation of the DDR has been advanced significantly and we will summarize recent progress below.

3. 1. DSB repair in the context of heterochromatin

The fact that chromatin is not a homogeneous structure raises the question whether breaks in heterochromatin are recognized and repaired with similar efficiency and using the same repair machinery as euchromatic breaks (Figure 1). Heterochromatin is a cytologically distinct region of the nucleus, which is highly enriched for repetitive DNA sequences that form a compacted chromatin structure harboring repressive histone marks such as trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9me3) and H3K9me3-associated heterochromatin proteins (HPs) [75]. Repression of repetitive DNA is thought to protect from aberrant recombination between homologous chromosome fragments and appears to suppress induction of aberrant DNA breaks [76]. Heterochromatin was also found to suppress reciprocal homologous recombination in pericentric heterochromatin during meiosis [77]. On the flip side, this compacted chromatin environment poses an impediment to DSB repair: heterochromatin was found refractory to the induction of the DDR as measured by reduced H2AX phosphorylation in yeast and mammals [78], and ionizing radiation (IR) induced DSBs are repaired with slower kinetics in heterochromatin than in euchromatin [79, 80]. Supporting a model of delayed access, displacement (or artificial depletion) of HP1 and its binding partner KAP1, both architectural components of heterochromatin, accelerates the DNA repair process [64, 80]. While the latter is dependent on ATM-mediated phosphorylation of KAP1, the former has been shown to require casein kinase (CK) 2 mediated HP1 phosphorylation [64, 80], likely reflecting different phases of the DDR. DNA damage-induced displacement of HP1 has further been linked to the recruitment of the acetyltransferase Tip60 [26]. Specifically, loss of HP1 from H3K9me3 allows Tip60 to bind H3K9me3 via its chromo-domain, which in turn renders DSB-associated chromatin accessible for downstream repair factors (see 2.2.).

Repair of DNA lesions in a repressive chromatin environment was further shown to involve a unique structural reorganization process to prevent aberrant recombination. Studies in S. cerevisiae demonstrated that DSBs in the highly repetitive ribosomal DNA (rDNA) are transiently relocalized to the extra-nucleolar space, where they form repair foci, a process involving the structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) group proteins Smc5 and Smc6 [81, 82]. Recent work in Drosophila demonstrated a similar, highly dynamic reorganization of metazoan heterochromatin in response to IR-mediated DSBs. The authors found that, while the initiation of the DDR involving phosphorylation of H2Av and resection of broken chromsome ends occurs within the heterochromatic environment, damage signaling subsequently promotes expansion of HP1α domains, and DNA lesions relocate to the periphery of heterochromatic regions where HR is completed. This structural reorganization was found to be dependent on ATM/ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related) kinase activity. As has been observed for yeast rDNA, accurate resolution of heterochromatic DSBs further required the Smc5/6 complex. The authors show that Smc5/6 associates with heterochromatin in an HP1α-dependent manner, where it prohibits the accumulation of the downstream HR mediator Rad51 at resected DNA ends, thereby preventing aberrant repair prior to protrusion of the break to the heterochromatic periphery [83]. If and how chromatin alterations may contribute to the formation and repair of these protrusions is at this point unclear. An interesting possibility is that, upon protrusion, HP1 may be lost from DSB-containing DNA, thereby exposing the silent H3K9me3 mark, which may in turn promote further chromatin relaxation via recruitment of Tip60 (see above and Figure 1B).

3. 2. Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci and DNA damage signaling

In addition to constitutive heterochromatic regions such as pericentromeric or telomeric repeats, facultative, or induced, heterochromatin can also influence the repair process. Prominent examples are oncogene-induced senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF). SAHF are specialized heterochromatin domains associated with H3K9me3, recruitment of the H3K9me3 binding protein HP1 and enrichment of macroH2A [84]. SAHF contribute to irreversible cell cycle exit in senescent cells by directly repressing the expression of E2F-regulated cell cycle genes [85]. Recently, SAHF were suggested to balance the DDR and concomitant p53 activation induced by replication stress following oncogene activation, thereby promoting survival and senescence rather than apoptosis. The authors show that SAHF formation is dependent on ATR kinase, a key DDR mediator of replication-associated DNA damage. Interestingly, DAPI-dense SAHF in oncogene-induced senescent (OIS) cells were found to be devoid of DDR markers such as γ-H2AX, MRN or activated ATM (phospho-ATM), suggesting that SAHF locally restrain the DDR [86]. More importantly, when heterochromatin formation was perturbed in OIS cells using RNAi-mediated depletion of HP1-γ or the SUV39 histone methyltransferase, which is responsible for trimethylation of H3K9, the DDR markersγ-H2AX, Nbs1 and phospho-ATM were found in DAPI dense regions and DDR signaling was increased. Similar results were obtained using pharmacological inhibition of SUV39 or class I and II HDAC activity. Concomitant activation of p53 suggested that the increase in DDR signaling in response to heterochromatin perturbation can extend beyond sites of damage. How DDR signaling is attenuated in the presence of SAHF is at this point unclear, especially given that the sites of damage appear not to coincide with sites of SAHF formation [86]. The absence of repair foci in H3K9me3 chromatin is further at odds with the observation that H3K9me3 can promote DSB repair via recruitment of Tip60 (see 2.2.) and more work is needed to understand the precise role of SAHF in DSB repair.

Together, these findings suggest a complex role for the chromatin environment in DNA repair. On one hand, highly compacted heterochromatin may shield DNA from sources of DNA damage, on the other hand it limits access of repair factors and consequently requires major structural remodeling, thereby influencing kinetics and possibly choice of repair pathways. Lastly, facultative heterochromatin can attenuate the DDR in a global but as of yet unexplored manner, pointing to chromatin as a new means to modulate repair outcome and downstream events such as apoptosis or cell cycle arrest.

4. Global nuclear changes triggered by DSBs

We have highlighted recent progress demonstrating the influence of the DSB-proximal chromatin environment on DNA repair. In the following we will discuss a less well-understood phenomenon, the global impact of DNA damage and DSBs in particular on chromatin structure and nuclear organization beyond the site of damage.

4. 1. Reorganization of chromatin in response to DNA damage

In the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, relocalization of silent information regulator (SIR) proteins in response to DSBs results in significant epigenetic deregulation [87–90]. SIR proteins form a complex that generates and propagates repressive chromatin at telomeres and other heterochromatic loci and redistribution of SIR proteins to DSBs results in the disruption of this complex and concomitant derepression of silent loci. Recently, we have shown that DNA damage can trigger a similar phenomenon in mammalian cells. The protein-deacetylase and SIR2 ortholog SIRT1 was found to redistribute on chromatin to sites of DNA damage in an ATM dependent manner. Accordingly, oxidative stress resulted in gene expression changes of otherwise SIRT1 regulated loci, a phenomenon that was also observed in the aging brain [91]. We refer to this evolutionarily conserved redistribution of chromatin modifiers as RCM response, a process that links DNA damage to epigenetic remodeling at ostensibly undamaged genomic loci [92]. This finding is reminiscent of an observation by Cremer and Cremer in 1986, where focal UV irradiation resulted in generalized chromosome shattering resembling a chromosome condensation failure [93]. This phenomenon was sensitive to inhibition of ATR by caffeine and the authors proposed a factor depletion model where a limited pool of protein is involved in both DNA repair and chromatin condensation. Both observations suggest that ATM and/or ATR can translate a local DNA damage signal into a nucleus-wide epigenetic response (Figure 2), a hypothesis that is further supported by the ATM-mediated inhibition of RNA polymerase I in response to damage that did not coincide with sites of Pol I activity [61]. Interestingly, the DSB repair factor and ubiquitin ligase BRCA1 has recently been implicated in the maintenance of pericentromeric satellite repeat silencing. It remains to be seen if BRCA1 is also redistributed in response to DNA damage, thereby causing derepression of pericentromeric heterochromatin, a process the authors suggest to be responsible for the genomic instability observed in BRCA1 mutant tumor cells [94].

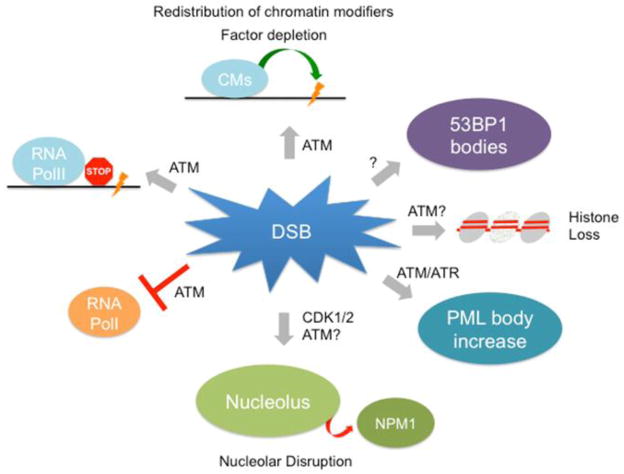

Figure 2. Global impact of DSBs on nuclear integrity.

DSBs can cause a variety of changes to chromatin structure and overall nuclear organization, all of which can have a profound impact on nuclear integrity and ultimately cell function (see text, section 4). Interestingly, the majority of these changes appear to depend on DNA damage signaling involving ATM and/or ATR kinases, suggesting global translation of a local DNA damage signal. CM, chromatin modifier.

The dramatic impact of DNA damage on global chromatin organization is further highlighted by two recent reports describing DSB-induced chromatid cohesion in G2/M phase in yeast [95, 96]. Cohesion between sister chromatids was thought to be dependent on DNA replication and, thus, restricted to S phase. This model was challenged by the observation that the DDR can promote de novo cohesion after replication is complete. Perhaps more intriguingly, this phenomenon was not limited to sites of DSBs but extended to undamaged sister-chromatids in trans. Genome-wide cohesion in response to focal DSBs was shown to require the acetyltransferase domain of the cohesion establishment factor Eco1 (ESCO1 in humans) as well as DNA damage checkpoint activation. Notably, genome-wide reinforcement of cohesion in response to IR in human cells has recently been shown to depend on ESCO1, suggesting evoluntionary conservation of this process [97].

Additional evidence for DNA damage-induced remodeling of undamaged chromatin comes from the observation that telomeric damage induced a global loss of core histones [97]. Interestingly, histone loss is also associated with cellular senescence both in yeast and mammalian cells [97, 98, 99], highlighting the functional significance of (DNA damage-induced) chromatin perturbations across species.

4. 2. DNA damage and nuclear bodies

A key feature of the eukaryotic nucleus is its high degree of compartmentalization, which forms many functionally distinct nuclear structures, including promyelocytic leukemia (PML) bodies, nucleoli and nuclear speckles [101]. Although the organization of nuclear bodies goes beyond chromatin, recent work suggests a link between the two as many histone-modifying enzymes were found to be associated with these nuclear compartments [102]. In general, nuclear bodies are thought to segregate distinct nuclear components by their function and thereby increase the efficiency of nuclear processes such as ribosomal RNA synthesis, transcription and RNA processing. Increasing evidence indicates that DSBs have a striking effect on the organization of nuclear bodies, which in turn may have severe consequences for cell function.

Diverse forms of DNA damage, ranging from chemotherapeutic genotoxins to ionizing radiation, were shown to induce an increase in the frequency of PML bodies, which are implicated in transcription, DNA replication and DNA repair [101]. Further investigation demonstrated that this phenomenon is controlled by a supra-molecular fission mechanism characterized by distortions in shape as well as fusion events and is delayed or inhibited by the loss of function of the repair factors NBS1, ATM, Chk2, or ATR [103]. The latter have been reported to localize to PML bodies in a temporally regulated manner prior to and following DNA damage [103], resulting in close juxtaposition of PML bodies with DNA repair foci, persisting up to 24 h after damage [103, 104]. These observations suggest that PML bodies play a role in modulating damage signaling or break repair itself. Consistently, PML knockout mice exhibit an elevated incidence of tumors in response to carcinogens [105, 106] and cells derived from these animals have an increased level of sister chromatid exchange and concomitant chromosomal instability [107].

In addition to their effect on PML bodies, DSBs were also shown to disrupt nucleolar structure [108], although the mechanism for this disruption is only beginning to be understood. Recently, it has been demonstrated that NPM1 (nucleophosmin 1), a histone chaperone and key structural component of the nucleolus, shuttles from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm in response to various types of DNA damage and cellular stress, and is further recruited to DSB lesions in a phosphorylated form [109]. Replacement of endogenous NPM1 with its nonphosphorylable T199A mutant delayed the resolution of IR-induced RAD51 foci. T199 phosphorylation of NPM1 is mediated by the cyclin dependent kinases CDK1 and CDK2, which in turn play a key role in NPM1 dissociation from nucleolar components. It is tempting to speculate that the DSB-induced inhibition of rRNA synthesis described in 2.4. has evolved as a consequence of DNA damage induced nucleolar disruption [61], as reduced rDNA transcription is expected to decrease the risk of genomic aberrations, particularly in the absence of key structural components such as NPM1. The biological relevance for DNA damage induced nucleolar disruption is still a matter of debate; an interesting theory is that the nucleolus serves as a central hub for coordinating the nuclear stress response, providing immediate release of critical first responders including DNA repair factors [108].

Taken together, the redistribution of chromatin modifiers and the reorganization of nuclear sub-structures are expected to have a genome-wide impact on both gene expression and epigenomic stability, and persisting DNA damage could thereby contribute to functional decline of cells and tissues as it is observed with age [110].

5. Perspective

Over the past decade, it has become evident that the maintenance of genomic integrity is highly dependent on dynamic changes in the chromatin environment. Recent research has identified a growing number of chromatin components, remodelers and modifications that play critical roles in DSB repair and have the potential to influence repair outcome and kinetics. However, many important questions remain: Do chromatin modifications determine the choice between the two major repair pathways, HR and NHEJ? How are chromatin marks restored once the repair process is completed? What is the functional relevance of a compacted chromatin structure at sites of damage and does it contribute to persisting structural changes to “remember” damage? Moreover, it is becoming increasingly evident that the biological impact of genotoxic stress goes beyond structural changes at the sites of damage. Genome-wide nuclear reorganization appears to be a central aspect of the DNA damage response and ranges from the disruption or alteration of nuclear bodies to the redistribution of chromatin modifiers to the loss of the basic building blocks of chromatin. Understanding the complex interplay between DNA damage and nuclear organization will, therefore, be a key task for future research and is expected to provide new insight into a process that affects cell function at its core.

Highlights.

Chromatin reorganization is a key aspect of eukaryotic DNA repair.

DNA break-induced chromatin remodeling affects repair factor access and choice.

The pre-existing chromatin environment influences DNA repair kinetics and outcome.

DNA breaks cause epigenomic changes that extend beyond the site of damage.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to authors who’s original work we were unable to cite due to space limitations. L.S. and P.O. were supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIH, The National Cancer Institute, The Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Talbert PB, Henikoff S. Histone variants--ancient wrap artists of the epigenome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:264–275. doi: 10.1038/nrm2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JS, Smith E, Shilatifard A. The language of histone crosstalk. Cell. 2010;142:682–685. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell. 2010;40:179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polo SE, Jackson SP. Dynamics of DNA damage response proteins at DNA breaks: a focus on protein modifications. Genes Dev. 2011;25:409–433. doi: 10.1101/gad.2021311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Misteli T, Soutoglou E. The emerging role of nuclear architecture in DNA repair and genome maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:243–254. doi: 10.1038/nrm2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N. Assembly and function of DNA double-strand break repair foci in mammalian cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogakou EP, Boon C, Redon C, Bonner WM. Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:905–916. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groth A, Rocha W, Verreault A, Almouzni G. Chromatin challenges during DNA replication and repair. Cell. 2007;128:721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg RA. Histone tails: Directing the chromatin response to DNA damage. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2883–2890. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smerdon MJ, Lieberman MW. Nucleosome rearrangement in human chromatin during UV-induced DNA- reapir synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:4238–4241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.9.4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruhlak MJ, Celeste A, Dellaire G, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Muller WG, McNally JG, Bazett-Jones DP, Nussenzweig A. Changes in chromatin structure and mobility in living cells at sites of DNA double-strand breaks. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:823–834. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YC, Gerlitz G, Furusawa T, Catez F, Nussenzweig A, Oh KS, Kraemer KH, Shiloh Y, Bustin M. Activation of ATM depends on chromatin interactions occurring before induction of DNA damage. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:92–96. doi: 10.1038/ncb1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clapier CR, Cairns BR. The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:273–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.062706.153223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison AJ, Shen X. Chromatin remodelling beyond transcription: the INO80 and SWR1 complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:373–384. doi: 10.1038/nrm2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smeenk G, Wiegant WW, Vrolijk H, Solari AP, Pastink A, van Attikum H. The NuRD chromatin-remodeling complex regulates signaling and repair of DNA damage. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:741–749. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201001048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polo SE, Kaidi A, Baskcomb L, Galanty Y, Jackson SP. Regulation of DNA-damage responses and cell-cycle progression by the chromatin remodelling factor CHD4. EMBO J. 2010;29:3130–3139. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen DH, Poinsignon C, Gudjonsson T, Dinant C, Payne MR, Hari FJ, Danielsen JM, Menard P, Sand JC, Stucki M, Lukas C, Bartek J, Andersen JS, Lukas J. The chromatin-remodeling factor CHD4 coordinates signaling and repair after DNA damage. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:731–740. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robert T, Vanoli F, Chiolo I, Shubassi G, Bernstein KA, Rothstein R, Botrugno OA, Parazzoli D, Oldani A, Minucci S, Foiani M. HDACs link the DNA damage response, processing of double-strand breaks and autophagy. Nature. 2011;471:74–79. doi: 10.1038/nature09803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller KM, Tjeertes JV, Coates J, Legube G, Polo SE, Britton S, Jackson SP. Human HDAC1 and HDAC2 function in the DNA-damage response to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1144–1151. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou DM, Adamson B, Dephoure NE, Tan X, Nottke AC, Hurov KE, Gygi SP, Colaiacovo MP, Elledge SJ. A chromatin localization screen reveals poly (ADP ribose)-regulated recruitment of the repressive polycomb and NuRD complexes to sites of DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18475–18480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012946107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai AY, Wade PA. Cancer biology and NuRD: a multifaceted chromatin remodelling complex. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:588–596. doi: 10.1038/nrc3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou DM, Adamson B, Dephoure NE, Tan X, Nottke AC, Hurov KE, Gygi SP, Colaiacovo MP, Elledge SJ. A chromatin localization screen reveals poly (ADP ribose)-regulated recruitment of the repressive polycomb and NuRD complexes to sites of DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:18475–18480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012946107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chi P, Allis CD, Wang GG. Covalent histone modifications--miswritten, misinterpreted and mis-erased in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:457–469. doi: 10.1038/nrc2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murr R, Loizou JI, Yang YG, Cuenin C, Li H, Wang ZQ, Herceg Z. Histone acetylation by Trrap-Tip60 modulates loading of repair proteins and repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:91–99. doi: 10.1038/ncb1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, Jiang X, Xu Y, Ayrapetov MK, Moreau LA, Whetstine JR, Price BD. Histone H3 methylation links DNA damage detection to activation of the tumour suppressor Tip60. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1376–1382. doi: 10.1038/ncb1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masumoto H, Hawke D, Kobayashi R, Verreault A. A role for cell-cycle-regulated histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation in the DNA damage response. Nature. 2005;436:294–298. doi: 10.1038/nature03714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CC, Carson JJ, Feser J, Tamburini B, Zabaronick S, Linger J, Tyler JK. Acetylated lysine 56 on histone H3 drives chromatin assembly after repair and signals for the completion of repair. Cell. 2008;134:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das C, Lucia MS, Hansen KC, Tyler JK. CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 56. Nature. 2009;459:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature07861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michishita E, McCord RA, Boxer LD, Barber MF, Hong T, Gozani O, Chua KF. Cell cycle-dependent deacetylation of telomeric histone H3 lysine K56 by human SIRT6. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2664–2666. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.16.9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang B, Zwaans BM, Eckersdorff M, Lombard DB. The sirtuin SIRT6 deacetylates H3 K56Ac in vivo to promote genomic stability. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2662–2663. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.16.9329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doil C, Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Menard P, Larsen DH, Pepperkok R, Ellenberg J, Panier S, Durocher D, Bartek J, Lukas J, Lukas C. RNF168 binds and amplifies ubiquitin conjugates on damaged chromosomes to allow accumulation of repair proteins. Cell. 2009;136:435–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huen MS, Grant R, Manke I, Minn K, Yu X, Yaffe MB, Chen J. RNF8 transduces the DNA-damage signal via histone ubiquitylation and checkpoint protein assembly. Cell. 2007;131:901–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Faustrup H, Melander F, Bartek J, Lukas C, Lukas J. RNF8 ubiquitylates histones at DNA double-strand breaks and promotes assembly of repair proteins. Cell. 2007;131:887–900. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart GS, Panier S, Townsend K, Al-Hakim AK, Kolas NK, Miller ES, Nakada S, Ylanko J, Olivarius S, Mendez M, Oldreive C, Wildenhain J, Tagliaferro A, Pelletier L, Taubenheim N, Durandy A, Byrd PJ, Stankovic T, Taylor AM, Durocher D. The RIDDLE syndrome protein mediates a ubiquitin-dependent signaling cascade at sites of DNA damage. Cell. 2009;136:420–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim H, Chen J, Yu X. Ubiquitin-binding protein RAP80 mediates BRCA1-dependent DNA damage response. Science. 2007;316:1202–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1139621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sobhian B, Shao G, Lilli DR, Culhane AC, Moreau LA, Xia B, Livingston DM, Greenberg RA. RAP80 targets BRCA1 to specific ubiquitin structures at DNA damage sites. Science. 2007;316:1198–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.1139516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang B, Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Zhang D, Smogorzewska A, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. Abraxas and RAP80 form a BRCA1 protein complex required for the DNA damage response. Science. 2007;316:1194–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1139476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moyal L, Lerenthal Y, Gana-Weisz M, Mass G, So S, Wang SY, Eppink B, Chung YM, Shalev G, Shema E, Shkedy D, Smorodinsky NI, van Vliet N, Kuster B, Mann M, Ciechanover A, Dahm-Daphi J, Kanaar R, Hu MC, Chen DJ, Oren M, Shiloh Y. Requirement of ATM-dependent monoubiquitylation of histone H2B for timely repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell. 2011;41:529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakamura K, Kato A, Kobayashi J, Yanagihara H, Sakamoto S, Oliveira DV, Shimada M, Tauchi H, Suzuki H, Tashiro S, Zou L, Komatsu K. Regulation of homologous recombination by RNF20-dependent H2B ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2011;41:515–528. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shanbhag NM, Rafalska-Metcalf IU, Balane-Bolivar C, Janicki SM, Greenberg RA. ATM-dependent chromatin changes silence transcription in cis to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell. 2010;141:970–981. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang H, Wang L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Vidal M, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in Polycomb silencing. Nature. 2004;431:873–878. doi: 10.1038/nature02985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pavri R, Zhu B, Li G, Trojer P, Mandal S, Shilatifard A, Reinberg D. Histone H2B monoubiquitination functions cooperatively with FACT to regulate elongation by RNA polymerase II. Cell. 2006;1972:703–717. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ginjala V, Nacerddine K, Kulkarni A, Oza J, Hill SJ, Yao M, Citterio E, van Lohuizen M, Ganesan S. BMI1 is recruited to DNA breaks and contributes to DNA damage-induced H2A ubiquitination and repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1972–1982. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00981-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galanty Y, Belotserkovskaya R, Coates J, Polo S, Miller KM, Jackson SP. Mammalian SUMO E3-ligases PIAS1 and PIAS4 promote responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Nature. 2009;462:935–939. doi: 10.1038/nature08657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N. The ubiquitin- and SUMO-dependent signaling response to DNA double-strand breaks. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2914–2919. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalocsay M, Hiller NJ, Jentsch S. Chromosome-wide Rad51 spreading and SUMO-H2A.Z-dependent chromosome fixation in response to a persistent DNA double-strand break. Mol Cell. 2009;33:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Botuyan MV, Lee J, Ward IM, Kim JE, Thompson JR, Chen J, Mer G. Structural basis for the methylation state-specific recognition of histone H4-K20 by 53BP1 and Crb2 in DNA repair. Cell. 2006;127:1361–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.FitzGerald JE, Grenon M, Lowndes NF. 53BP1: function and mechanisms of focal recruitment. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:897–904. doi: 10.1042/BST0370897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pei H, Zhang L, Luo K, Qin Y, Chesi M, Fei F, Bergsagel PL, Wang L, You Z, Lou Z. MMSET regulates histone H4K20 methylation and 53BP1 accumulation at DNA damage sites. Nature. 2011;470:124–128. doi: 10.1038/nature09658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huyen Y, Zgheib O, Ditullio RA, Jr, Gorgoulis VG, Zacharatos P, Petty TJ, Sheston EA, Mellert HS, Stavridi ES, Halazonetis TD. Methylated lysine 79 of histone H3 targets 53BP1 to DNA double-strand breaks. Nature. 2004;432:406–411. doi: 10.1038/nature03114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bunting SF, Callen E, Wong N, Chen HT, Polato F, Gunn A, Bothmer A, Feldhahn N, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Cao L, Xu X, Deng CX, Finkel T, Nussenzweig M, Stark JM, Nussenzweig A. 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in Brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell. 2010;141:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bouwman P, Aly A, Escandell JM, Pieterse M, Bartkova J, van der Gulden H, Hiddingh S, Thanasoula M, Kulkarni A, Yang Q, Haffty BG, Tommiska J, Blomqvist C, Drapkin R, Adams DJ, Nevanlinna H, Bartek J, Tarsounas M, Ganesan S, Jonkers J. 53BP1 loss rescues BRCA1 deficiency and is associated with triple-negative and BRCA-mutated breast cancers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:688–695. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papamichos-Chronakis M, Krebs JE, Peterson CL. Interplay between Ino80 and Swr1 chromatin remodeling enzymes regulates cell cycle checkpoint adaptation in response to DNA damage. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2437–2449. doi: 10.1101/gad.1440206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kusch T, Florens L, Macdonald WH, Swanson SK, Glaser RL, Yates JR, 3rd, Abmayr SM, Washburn MP, Workman JL. Acetylation by Tip60 is required for selective histone variant exchange at DNA lesions. Science. 2004;306:2084–2087. doi: 10.1126/science.1103455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Timinszky G, Till S, Hassa PO, Hothorn M, Kustatscher G, Nijmeijer B, Colombelli J, Altmeyer M, Stelzer EH, Scheffzek K, Hottiger MO, Ladurner AG. A macrodomain-containing histone rearranges chromatin upon sensing PARP1 activation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:923–929. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yelamos J, Farres J, Llacuna L, Ampurdanes C, Martin-Caballero J. PARP-1 and PARP-2: New players in tumour development. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:328–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doyen CM, An W, Angelov D, Bondarenko V, Mietton F, Studitsky VM, Hamiche A, Roeder RG, Bouvet P, Dimitrov S. Mechanism of polymerase II transcription repression by the histone variant macroH2A. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1156–1164. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.1156-1164.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim MY, Mauro S, Gevry N, Lis JT, Kraus WL. NAD+-dependent modulation of chromatin structure and transcription by nucleosome binding properties of PARP-1. Cell. 2004;119:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krishnakumar R, Kraus WL. PARP-1 regulates chromatin structure and transcription through a KDM5B-dependent pathway. Mol Cell. 2010;39:736–749. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kruhlak M, Crouch EE, Orlov M, Montano C, Gorski SA, Nussenzweig A, Misteli T, Phair RD, Casellas R. The ATM repair pathway inhibits RNA polymerase I transcription in response to chromosome breaks. Nature. 2007;447:730–734. doi: 10.1038/nature05842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luijsterburg MS, Dinant C, Lans H, Stap J, Wiernasz E, Lagerwerf S, Warmerdam DO, Lindh M, Brink MC, Dobrucki JW, Aten JA, Fousteri MI, Jansen G, Dantuma NP, Vermeulen W, Mullenders LH, Houtsmuller AB, Verschure PJ, van Driel R. Heterochromatin protein 1 is recruited to various types of DNA damage. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:577–586. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200810035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baldeyron C, Soria G, Roche D, Cook AJ, Almouzni G. HP1alpha recruitment to DNA damage by p150CAF-1 promotes homologous recombination repair. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:81–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201101030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ayoub N, Jeyasekharan AD, Bernal JA, Venkitaraman AR. HP1-beta mobilization promotes chromatin changes that initiate the DNA damage response. Nature. 2008;453:682–686. doi: 10.1038/nature06875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ayoub N, Jeyasekharan AD, Venkitaraman AR. Mobilization and recruitment of HP1: a bimodal response to DNA breakage. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2945–2950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cuozzo C, Porcellini A, Angrisano T, Morano A, Lee B, Di Pardo A, Messina S, Iuliano R, Fusco A, Santillo MR, Muller MT, Chiariotti L, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV. DNA damage, homology-directed repair, and DNA methylation. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 67.Lee GE, Kim JH, Taylor M, Muller MT. DNA methyltransferase 1-associated protein (DMAP1) is a co-repressor that stimulates DNA methylation globally and locally at sites of double strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37630–37640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.148536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O'Hagan HM, Mohammad HP, Baylin SB. Double strand breaks can initiate gene silencing and SIRT1-dependent onset of DNA methylation in an exogenous promoter CpG island. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O'Hagan HM, Wang W, Sen S, Shields CD, Lee SS, Zhang YW, Clements EG, Cai Y, Van Neste L, Easwaran H, Casero RA, Sears CL, Baylin SB. Oxidative damage targets complexes containing DNA methyltransferases, SIRT1, and polycomb members to promoter CpG islands. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:606–619. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Soutoglou E, Dorn JF, Sengupta K, Jasin M, Nussenzweig A, Ried T, Danuser G, Misteli T. Positional stability of single double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:675–682. doi: 10.1038/ncb1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harrigan JA, Belotserkovskaya R, Coates J, Dimitrova DS, Polo SE, Bradshaw CR, Fraser P, Jackson SP. Replication stress induces 53BP1-containing OPT domains in G1 cells. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:97–108. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201011083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lukas C, Savic V, Bekker-Jensen S, Doil C, Neumann B, Pedersen RS, Grofte M, Chan KL, Hickson ID, Bartek J, Lukas J. 53BP1 nuclear bodies form around DNA lesions generated by mitotic transmission of chromosomes under replication stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:243–253. doi: 10.1038/ncb2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Durkin SG, Glover TW. Chromosome fragile sites. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:169–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.165900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Charville GW, Rando TA. Stem cell ageing and non-random chromosome segregation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 366:85–93. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nakayama J, Rice JC, Strahl BD, Allis CD, Grewal SI. Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science. 2001;292:110–113. doi: 10.1126/science.1060118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peng JC, Karpen GH. Heterochromatic genome stability requires regulators of histone H3 K9 methylation. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Westphal T, Reuter G. Recombinogenic effects of suppressors of position-effect variegation in Drosophila. Genetics. 2002;160:609–621. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim JA, Kruhlak M, Dotiwala F, Nussenzweig A, Haber JE. Heterochromatin is refractory to gamma-H2AX modification in yeast and mammals. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:209–218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cowell IG, Sunter NJ, Singh PB, Austin CA, Durkacz BW, Tilby MJ. gammaH2AX foci form preferentially in euchromatin after ionising-radiation. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Goodarzi AA, Noon AT, Deckbar D, Ziv Y, Shiloh Y, Lobrich M, Jeggo PA. ATM signaling facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks associated with heterochromatin. Mol Cell. 2008;31:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Torres-Rosell J, Sunjevaric I, De Piccoli G, Sacher M, Eckert-Boulet N, Reid R, Jentsch S, Rothstein R, Aragon L, Lisby M. The Smc5-Smc6 complex and SUMO modification of Rad52 regulates recombinational repair at the ribosomal gene locus. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:923–931. doi: 10.1038/ncb1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Torres-Rosell J, De Piccoli G, Aragon L. Can eukaryotic cells monitor the presence of unreplicated DNA? Cell Div. 2007;2:19. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chiolo I, Minoda A, Colmenares SU, Polyzos A, Costes SV, Karpen GH. Double-strand breaks in heterochromatin move outside of a dynamic HP1a domain to complete recombinational repair. Cell. 2011;144:732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang R, Poustovoitov MV, Ye X, Santos HA, Chen W, Daganzo SM, Erzberger JP, Serebriiskii IG, Canutescu AA, Dunbrack RL, Pehrson JR, Berger JM, Kaufman PD, Adams PD. Formation of MacroH2A-containing senescence-associated heterochromatin foci and senescence driven by ASF1a and HIRA. Dev Cell. 2005;8:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Narita M, Nunez S, Heard E, Lin AW, Hearn SA, Spector DL, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell. 2003;113:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Di Micco R, Sulli G, Dobreva M, Liontos M, Botrugno OA, Gargiulo G, dal Zuffo R, Matti V, d’Ario G, Montani E, Mercurio C, Hahn WC, Gorgoulis V, Minucci S, d’Adda di Fagagna F. Interplay between oncogene-induced DNA damage response and heterochromatin in senescence and cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:292–302. doi: 10.1038/ncb2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mills KD, Sinclair DA, Guarente L. MEC1-dependent redistribution of the Sir3 silencing protein from telomeres to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell. 1999;97:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smeal T, Claus J, Kennedy B, Cole F, Guarente L. Loss of transcriptional silencing causes sterility in old mother cells of S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1996;84:633–642. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martin SG, Laroche T, Suka N, Grunstein M, Gasser SM. Relocalization of telomeric Ku and SIR proteins in response to DNA strand breaks in yeast. Cell. 1999;97:621–633. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McAinsh AD, Scott-Drew S, Murray JA, Jackson SP. DNA damage triggers disruption of telomeric silencing and Mec1p-dependent relocation of Sir3p. Curr Biol. 1999;9:963–966. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80424-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Oberdoerffer P, Michan S, McVay M, Mostoslavsky R, Vann J, Park SK, Hartlerode A, Stegmuller J, Hafner A, Loerch P, Wright SM, Mills KD, Bonni A, Yankner BA, Scully R, Prolla TA, Alt FW, Sinclair DA. SIRT1 redistribution on chromatin promotes genomic stability but alters gene expression during aging. Cell. 2008;135:907–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oberdoerffer P, Sinclair DA. The role of nuclear architecture in genomic instability and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:692–702. doi: 10.1038/nrm2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cremer C, Cremer T. Induction of chromosome shattering by ultraviolet light and caffeine: the influence of different distributions of photolesions. Mutat Res. 1986;163:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(86)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhu Q, Pao GM, Huynh AM, Suh H, Tonnu N, Nederlof PM, Gage FH, Verma IM. BRCA1 tumour suppression occurs via heterochromatin-mediated silencing. Nature. 2011;477:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature10371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Strom L, Karlsson C, Lindroos HB, Wedahl S, Katou Y, Shirahige K, Sjogren C. Postreplicative formation of cohesion is required for repair and induced by a single DNA break. Science. 2007;317:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.1140649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Unal E, Heidinger-Pauli JM, Koshland D. DNA double-strand breaks trigger genome-wide sister-chromatid cohesion through Eco1 (Ctf7) Science. 2007;317:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.1140637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim BJ, Li Y, Zhang J, Xi Y, Yang T, Jung SY, Pan X, Chen R, Li W, Wang Y, Qin J. Genome-wide reinforcement of cohesin binding at pre-existing cohesin sites in response to ionizing radiation in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22784–22792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.134577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.O’Sullivan RJ, Kubicek S, Schreiber SL, Karlseder J. Reduced histone biosynthesis and chromatin changes arising from a damage signal at telomeres. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1218–1225. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Oberdoerffer P. An age of fewer histones. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1029–1031. doi: 10.1038/ncb1110-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Feser J, Truong D, Das C, Carson JJ, Kieft J, Harkness T, Tyler JK. Elevated histone expression promotes life span extension. Mol Cell. 2010;39:724–735. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhao R, Bodnar MS, Spector DL. Nuclear neighborhoods and gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Torok D, Ching RW, Bazett-Jones DP. PML nuclear bodies as sites of epigenetic regulation. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1325–1336. doi: 10.2741/3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dellaire G, Ching RW, Ahmed K, Jalali F, Tse KC, Bristow RG, Bazett-Jones DP. Promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies behave as DNA damage sensors whose response to DNA double-strand breaks is regulated by NBS1 and the kinases ATM, Chk2, and ATR. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:55–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carbone R, Pearson M, Minucci S, Pelicci PG. PML NBs associate with the hMre11 complex and p53 at sites of irradiation induced DNA damage. Oncogene. 2002;21:1633–1640. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang ZG, Ruggero D, Ronchetti S, Zhong S, Gaboli M, Rivi R, Pandolfi PP. PML is essential for multiple apoptotic pathways. Nat Genet. 1998;20:266–272. doi: 10.1038/3073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rego EM, Wang ZG, Peruzzi D, He LZ, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Role of promyelocytic leukemia (PML) protein in tumor suppression. J Exp Med. 2001;193:521–529. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.4.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhong S, Hu P, Ye TZ, Stan R, Ellis NA, Pandolfi PP. A role for PML and the nuclear body in genomic stability. Oncogene. 1999;18:7941–7947. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Boulon S, Westman BJ, Hutten S, Boisvert FM, Lamond AI. The nucleolus under stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Koike A, Nishikawa H, Wu W, Okada Y, Venkitaraman AR, Ohta T. Recruitment of phosphorylated NPM1 to sites of DNA damage through RNF8-dependent ubiquitin conjugates. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6746–6756. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sinclair DA, Oberdoerffer P. The ageing epigenome: damaged beyond repair? Ageing Res Rev. 2009;8:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]