Abstract

Although substance use disorders are associated with overall increased suicide risk, there is considerable variability in suicide risk among substance dependent individuals (SDIs). Impairment in impulse control is common among SDIs and may contribute to vulnerability to suicidal behavior. The present study examined the relation between one specific aspect of impulsivity, delay discounting, and suicide attempt history in a sample of SDIs. An interaction was observed between suicide attempt history and discounting rates across delayed reward size. Specifically, SDIs with no history of attempted suicide, devalued small relative to large delayed rewards. In contrast, SDIs with a history of suicide attempts appeared comparatively indifferent to delayed reward size, discounting both small and large delayed rewards at essentially identical rates. These findings provide evidence that, despite the view that SDIs are characterized by marked difficulties in impulsivity, significant variability nevertheless exists within this group in delay discounting tendencies. Furthermore, these differences provide preliminary evidence that specific aspects of impulsivity may help to identify those most at risk for suicidal behavior in this population. The potential implications of our findings for suicide prevention efforts are discussed.

Keywords: Delay Discounting, Impulsivity, Substance Use Disorders, Suicide

1. Introduction

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are associated with increased risk of suicide (Nock et al., 2008). Moreover, among individuals experiencing suicidal ideation in one cross-national study, the risk for subsequent suicide attempts was highest for those with SUDs (Nock et al., 2008). The majority of SDIs, however, never attempt suicide, raising the critical question of whether more specific predictors of risk for suicidal behavior can be identified within this population.

The construct of impulsivity (Goldstein & Volkow, 2002; Verdejo-Garcia & Perez-Garcia, 2007) has been broadly defined as “an individual’s predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli without regards to the negative consequences of these reactions to themselves or others” (Moeller et al., 2001). Impulsivity is considered a critical component in models of addiction and is commonly associated with suicide attempts (Dougherty et al., 2004) and completion (Dervic et al., 2008, Maser et al., 2002). Despite its intuitive appeal, investigations have not consistently documented an association between impulsivity and suicidal behavior among SDIs.

Recent models conceptualize impulsivity as a multidimensional rather than unidimensional construct, encompassing subtypes with distinct cognitive, behavioral, and underlying neural correlates (Barratt & Slaughter, 1998; Dougherty et al., 2003; Klonsky & May, 2010; Nigg, 2000). Few studies have applied this more complex model to investigate suicidal behavior among SDIs, but available data suggest its application has potential utility. Supporting evidence is provided by a recent finding (Klonsky & May, 2010) that a broad and unidimensional operational definition of impulsivity did not distinguish suicide attempters from ideators. In contrast, a multidimensional assessment of impulsivity revealed a selective relation between specific aspects of impulsivity (i.e., poor planning) and suicidal behavior.

Delay discounting (DD, or “impulsive choice”) is the tendency to undervalue an anticipated future reward as the time delay prior to obtaining the reward increases (Bickel et al., 2010; Dougherty et al., 2003; Green & Myerson, 2004). In general, people tend to prefer small immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards (Green, Myerson, & McFadden, 1997), and the rate that delayed rewards are discounted provides a behavioral index of impulsivity (Madden & Bickel, 2010). Additionally, the size of the delayed reward has been consistently found to influence temporal discounting behavior. Specifically, people tend to discount smaller delayed rewards at a higher rate than larger ones, a tendency that has been referred to as the magnitude effect (Green, Fry, & Myerson, 1994; Green & Myerson, 2004; Johnson & Bickel, 2002; Stranger et al., in press).

Higher discount rates have consistently been found among SDIs, including individuals dependent on alcohol (Bickel & Marsch, 2001; Petry, 2001), cocaine (Coffey et al., 2003), opioids (Bickel & Marsch, 2001; Kirby et al., 1999), and methamphetamine (Monterosso et al., 2007). DD has been relatively understudied in relation to suicide risk among SDIs despite its potential conceptual relevance. Although models of suicidal behavior typically focus on relief or escape from distress rather than appetitive rewards, they resemble DD by emphasizing the overwhelming importance of immediate outcome, which takes precedence over any future event (Dombrovski et al., 2011; van Heeringen et al., 2011).

Additionally, two cognitive components of DD, anticipatory time perception and sensitivity to reward, may be especially relevant to suicidal behavior among SDIs. Past studies have linked suicidality with impairments in future-directed thinking and time perception (Krysinska et al., 2006) and with oversensitivity to immediate reward (van Heeringen et al., 2011), which are also prominent characteristics among SDIs (Dawe & Loxton, 2004; Hogarth, 2011; Wittmann, Leland, Churan, & Paulus, 2007). Indirect support is also provided by fMRI studies of suicidal behavior, which have consistently noted abnormal activation in dorsolateral and orbitofrontal cortices, brain regions linked with temporal horizon and reward processing (van Heeringen et al., 2011).

These findings provide converging evidence that a link between DD and suicidal behavior could shed light on neurobiological mechanisms and more specific risk factors for suicide and inform the study of suicidality within this particularly high-risk population.

In the current study we administered a measure of DD to a large sample of SDIs with and without a history of suicide attempts. We hypothesized that (i) SDIs with a history of attempted suicide would discount delayed rewards at a significantly greater rate than would those with no history of suicide attempts; and that (ii) SDIs with no suicide attempt history would be less likely to discount large delayed rewards relative to small ones, whereas SDIs with a history of attempted suicide would be relatively unmoved by differences in delayed reward magnitude, given the importance of immediacy over any future event.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants in the current study consisted of 466 individuals with DSM-IV diagnosed SUDs (primarily cocaine or opioid dependence) enrolled in a larger study of neurocognitive effects of HIV and substance dependence. Participants were recruited from Jesse Brown VA Medical Center substance dependence programs, community clinics, and word of mouth. The inclusion criteria were: (a) absence of acute mania or major depression, (b) no documented history of neurologic AIDS-defining or other of neurologic illness or injury, including cerebrovascular accident, open head injury, closed head injury with loss of consciousness exceeding 30 minutes, neurosyphilis, seizure disorder, c) no history of schizophrenia, or current neuroleptic treatment and (e) negative Breathalyzer using a CMI SD2 Intoxilyzer (CMI. Owensboro, KY) and rapid urine toxicology screening for opiates and cocaine using Visualine V (Sun Biomedical Supplies, NJ) at the time of study visit. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards for the University of Illinois-Chicago (UIC) and the Jesse Brown VA. All subjects provided informed consent and were compensated for their time.

2.2. Measures

Lifetime history of substance use disorders, and unipolar and bipolar mood disorders

All subjects were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Substance Abuse Module and Mood Disorders Module (SCID-SAM; First et al., 1995) in order to determine lifetime history of SUDs, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder.

HIV and hepatitis C serostatus

HIV and hepatitis C serostatus were ELISA-verified at the time of study participation.

Suicide attempt history

History of suicide attempts was indexed from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1985), a semi-structured interview that assesses severity of alcohol and drug use, indices of employment, social and psychiatric status, and includes a question asking if the participant had attempted suicide at least once at any point in their life.

Delayed reward discounting task

All participants completed the Monetary Choice Questionnaire (MCQ; Kirby et al., 1999), a paper and pencil measure commonly used to index DD in SDIs. The measure consists of 27 two-choice items that pair a small immediate reward and a larger delayed reward (e.g., “Would you prefer to have $5 now or $10 one week from now?”), and subjects were instructed to select the more desirable reward. Subjects were instructed to respond in the same manner as they would with real money. To increase motivation, we informed participants that they had a one-in-six chance of obtaining an actual monetary reward, a commonly used procedure when administering the MCQ (see Kirby, Petry & Bickel, 1999 for details). After completing the questionnaire, participants rolled a die to determine if they would win a $10 reward. A preference for smaller immediate rewards over larger later ones is taken as being reflective of greater impulsivity (Ainslie, 1975).

2.3. Procedures

Prospective participants were administered an initial in-clinic or phone screen of medical and substance abuse history to determine their eligibility for study participation. Participants were instructed to abstain from all drug use for at least one week prior to their participation. To verify abstinence at each of their two study visits, participants completed a Breathalyzer test and rapid urine toxicology screen for opiates and cocaine. If a participant tested positive the visit was terminated without payment and the testing was rescheduled. The SCID and ASI were administered during the initial visit, whereas the DD task was completed during the second visit. The interval between first and second visits ranged from 5 to 21 days.

3. Data Analysis

For the DD task, each participant’s discount-rate parameter, k, was determined using Mazur’s (1987) hyperbolic discount function (i.e., V = A/[1+kD], where V is a future reward’s discounted value, A is its immediate value, and D is the delay interval) based on their choices across the 27 MCQ items and in a manner consistent with previous research (e.g., Businelle et al., 2010; Lampert & Pizzagalli, 2010). Larger k values are indicative of a higher discounting rate (i.e., greater impulsivity as defined by a preference for a small immediate reward over a larger delayed reward). As previous research has demonstrated an inverse relation between discount rates and magnitude of delayed reward (Kirby, 1997), we estimated discount rates separately for small ($25–35) and large ($75–85) delayed rewards as well as an overall discount rate across all delayed reward magnitudes. To satisfy assumptions of normality, and in a manner consistent with past research (e.g., Businelle et al., 2010; Lampert & Pizzagalli, 2010), we analyzed the log-transformed k values in ANCOVAs with suicide attempt history as the between-subjects variable and delayed reward size as the within-subjects variable. Given previous research associating DD performance with gender (Kirby & Maraković, 1996), HIV-risk (Chesson et al., 2006; Odum, Madden, Badger, & Bickel, 2000), hepatitis C-seropositive status (Huckans et al., 2011), anhedonia (Lambert & Pizzagalli, 2010), and bipolar disorder (Strakowski et al., 2009; Swann et al., 2009), we covaried gender, HIV-serostatus, hepatitis C-serostatus, and lifetime history of major depression and bipolar disorder.

4. Results

4.1. Participants’ characteristics

The study sample was 30.3% female, 82.8% African American, 12.7% Caucasian, 3.4% Hispanic, with a mean age of 42.2 years (SD = 8.2) and a mean of 11.6 years (SD = 1.8) of education. A total of 88 (18.9%) of the participants endorsed a history of attempted suicide.

Table 1 shows demographic, HIV and hepatitis C serostatus, substance use, and mood disorder characteristics as well as overall discounting rates for participants with and without a history of suicide attempts. We compared the groups on these characteristics using independent sample t tests for parametric data and chi-square tests for categorical data. Participants with a history of attempted suicide were more likely to be female (χ2 = 8.587, p < .01), and to have a positive history of major depression (χ2 = 12. 873, p < .001) or bipolar disorder (χ2 = 16.108, p < .001). We also found a history of suicide attempts was more strongly associated with positive HIV serostatus (χ2 = 14.384, p < .001). No group differences were observed in age, education, ethnicity, hepatitis C serostatus, or prevalence of lifetime alcohol, cocaine, or opioid dependence.

Table 1.

Demographic, descriptive characteristics of the sample, and log transformed k by group.

| Variable | − Suicide Attempt (n = 378) |

+ Suicide Attempt (n = 88) |

Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female) | 27.25% | 43.18% | χ2 = 8.587 | .003 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 12.70% | 12.50% | χ2 = .003 | .960 |

| African American | 82.80% | 81.81% | χ2 = .048 | .826 |

| Hispanic | 3.44% | 3.41% | χ2 < .001 | .989 |

| Other | 0.79% | 2.27% | χ2 = 1.471 | .225 |

| Age in years, M (S.D.) | 42.19 (8.24) | 42.16 (8.08) | t = −.027 | .979 |

| Education years, M (S.D.) | 11.62 (1.80) | 11.72 (2.04) | t = .387 | .699 |

| HIV-seropositive | 26.98% | 47.73% | χ2 = 14.38 | <.001 |

| Hepatitis C-seropositive | 17.46% | 22.99% | χ2 = 1.434 | .231 |

| Substance Dependence | ||||

| Alcohol | 74.54% | 76.14% | χ2 = .097 | .755 |

| Cocaine | 80.00% | 84.09% | χ2 = .768 | .381 |

| Opioid | 50.53% | 42.05% | χ2 = 2.05 | .152 |

| Mood Disorders | ||||

| Bipolar Disorder | 2.65% | 12.50% | χ2 = 16.11 | <.001 |

| Major Depression | 15.34% | 31.81% | χ2 = 12.87 | <.001 |

| DD log k | ||||

| Small reward | −1.395 (.035) | −1.362 (.077) | ||

| Large reward, | −1.630 (.041) | −1.406 (.090) |

4.2. Delay Discounting

Table 1 shows the log transformed k values for each group. We first examined whether SDIs with and without a history of attempted suicide differed on overall DD rates in a univariate ANCOVA, controlling for gender, HIV and hepatitis C serostatus, and lifetime major depression and bipolar disorder. No main effect was observed for suicide attempt history (F[1, 436] = 2.530, p = .11), with only hepatitis C serostatus yielding a significant main effect among the covariates (F[1, 436] = 5.200, p = .023).

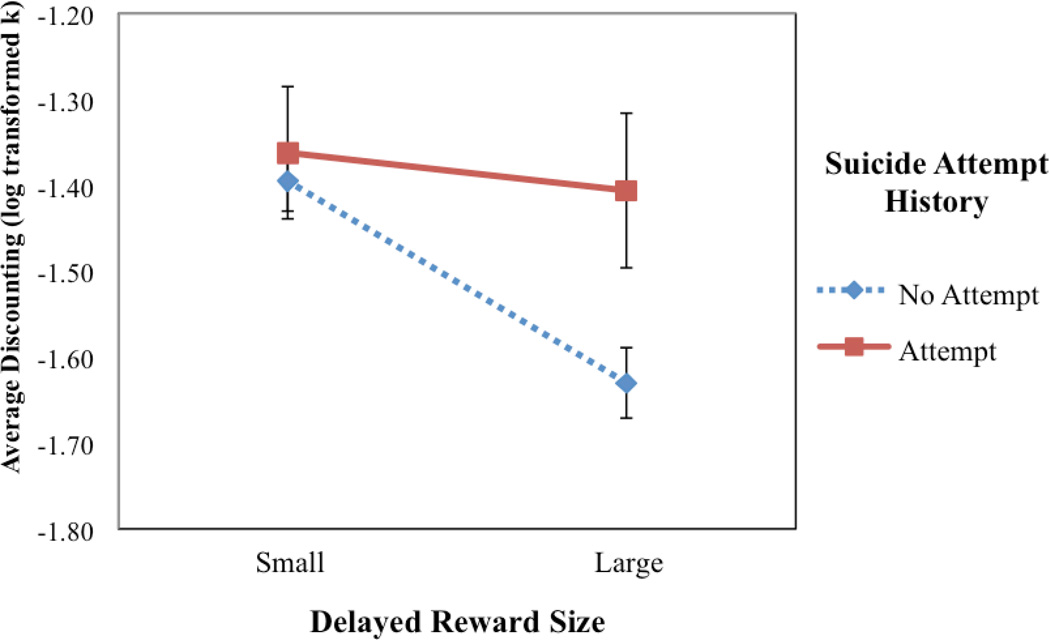

Next we conducted a 2 (suicide attempt history versus no attempt history) × 2 (small versus large delayed reward) mixed design ANCOVA with suicide attempt history as the between factor and reward size as the within factor, controlling for gender, HIV and hepatitis C serostatus, and lifetime major depression and bipolar disorder. We found a significant interaction between history of attempted suicide and delayed reward size, (F[1, 441] =5.674, p = .018) Follow-up pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections revealed that SDIs with no suicide attempt history discounted small delayed rewards more than large ones (F[1, 441] = 50.257, p < .001), whereas those with a history of attempted suicide showed no difference in discounting rates for small compared with large delayed rewards (F[1, 441] = .358, p = .550). Additionally, SDIs with and without a history of attempted suicide did not differ in discounting rates for small delayed rewards (F[1, 441] = .147, p = .702), but those with a history of attempted suicide showed a significantly higher discounting rate for large delayed rewards than did those with no suicide attempt history (F[1, 441] = 5.043, p = .025).

5. Discussion

The aim of the current study was to investigate DD in a large sample of SDIs with and without a history of attempted suicide. We provided a particularly conservative test of this association, controlling for the potential effects of gender, HIV and hepatitis C serostatus, as well as lifetime history of major depression and bipolar disorder on DD rates. Overall DD rates did not differ between the two groups. Instead, we found a significant interaction between suicide attempt history and size of the delayed reward. SDIs who previously attempted suicide appeared relatively indifferent to the magnitude of the delayed reward, exhibiting virtually identical discounting rates for both small and large delayed rewards. In contrast, SDIs without a history of attempted suicide displayed the more typical response pattern observed in studies of DD, reflecting a tendency to discount small delayed rewards more than large ones. Additionally, the two groups did not differ in discounting rate for small rewards, but SDIs with a history of suicide attempts discounted large delayed rewards at a higher rate than those with no history of suicide attempts.

These findings also lend weight to the view that although deficits in impulse control are common among SDIs, there is nevertheless substantial variability in impulsivity within this population (Vassileva, Gonzalez, Bechara, & Martin, 2007). In the current study, individual differences in DD appear to differentiate significantly between SDIs with and without a history of attempted suicide. Our conclusions are necessarily limited by the cross-sectional nature of the study, and although the current findings are consistent with the possibility that suicidal behavior in SDIs reflect impaired sensitivity to significant future rewards, no causal inferences can be made. Therefore, future research is required to replicate and to build on current findings by assessing the potential predictive validity of DD performance for future suicide attempts in SDIs. Additionally, and given increasing recognition of the complex relation between impulsivity and suicidal behavior (Klonsky & May, 2010), future studies should include measures of other types of impulsivity in the assessment of suicidality so as to ascertain which specific components of this multidimensional construct relate to suicidal behaviors in SDIs.

The current study compared discounting rates at fixed low and high delayed reward size. Future studies using a continuous measure of DD (e.g., response-based computerized programs; see Christakou, Brammer, & Rubia, 2011), especially with larger delayed rewards, will be important to determine whether SDI suicide attempters are responsive to larger delayed rewards or are truly insensitive to delayed reward magnitude. This is a particularly important consideration given the preliminary nature of the present findings in contrast to the robust finding of a magnitude effect in the general delay discounting literature.

It should also be noted that suicide attempt history was indexed by a dichotomous response to an item from the Addiction Severity Index, which did not permit more specific characterization of previous suicide attempts (e.g., distinguishing between planned and non-planned attempts). Insomuch as impulsivity is more strongly characteristic of non-planned suicide attempts (Conner, 2004), DD rates might at least in part contribute to this distinction. In this regard, a recent study of elderly non-SDIs who had attempted suicide found that those individuals reporting high-lethality and better planned suicide attempts were less likely to discount large delayed rewards than were low-lethality counterparts (Dombrovski et al., 2011).

Given the preliminary nature of our findings, further research is required and important insofar as it may eventually inform suicide prevention strategies (Brent, 1987; Conner, 2004). It is worth nothing, however, that Bickel and colleagues (2011) recently reported that substance dependent individuals who received computerized working memory training also showed improvement in delay discounting compared with a control group. The finding that delay discounting can be directly or indirectly modified suggests that cognitive interventions could potentially be associated with more effective suicide prevention.

Figure 1.

Lifetime history of attempted suicide moderates the relation between delayed reward size and discounting rates.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse R01 DA12828 to Eileen M. Martin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/adb

References

- Ainslie GW. Specious reward: A behavioral theory of impulsiveness and impulse control. Psychological Bulletin. 1975;82:463–496. doi: 10.1037/h0076860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt ES, Slaughter L. Defining, measuring, and predicting impulsive aggression: A heuristic model. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 1998;16:285–302. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0798(199822)16:3<285::aid-bsl308>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R, Landes RD, Hill PF, Baxter C. Remember the future: Working memory training decreases delay discounting among stimulant addicts. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jones BA, Landes RD, Christensen DR, Jackson L, Mancino M. Hypothetical intertemporal choice and real economic behavior: Delay discounting predicts voucher redemptions during contingency-management procedures. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18:546–552. doi: 10.1037/a0021739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA. Correlates of the medical lethality of suicide attempts in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1987;26:87–89. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198701000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:372–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Businelle MS, McVay MA, Kendzor D, Copeland A. A comparison of delay discounting among smokers, substance users, and non-dependent controls. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;112:247–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson HW, Leichliter JS, Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL, Bernstein DI, Fife KH. Discount rates and risky sexual behavior among teenagers and young adults. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 2006;32:217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Christakou A, Brammer M, Rubia K. Maturation of limbic corticostriatal activation and connectivity associated with developmental changes in temporal discounting. Neuroimage. 2011;54:1344–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Gudleski GD, Saladin ME, Brady KT. Impulsivity and rapid discounting of delayed hypothetical rewards in cocaine-dependent individuals. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11:18–25. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.11.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR. A call for research on planned vs. unplanned suicidal behavior. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004;34:89–98. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.2.89.32780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Loxton NJ. The role of impulsivity in the development of substance use and eating disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dervic K, Brent DA, Oquendo MA. Completed suicide in childhood. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2008;31:271–291. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrovski AY, Szanto K, Siegle GJ, Wallace ML, Forman SD, Sahakian B, Reynolds CF, III, Clark L. Lethal forethought: Delayed reward discounting differentiates high- and low-lethality suicide attempts in old age. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;70:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Bjork JM, Harper A, Marsh DM, Moeller FG, Mathias CW, Swann AC. Behavioral impulsivity paradigms: a comparison in hospitalized adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1145–1157. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Mathias CW, Marsh DM, Papageorgiou TD, Swann AC, Moeller FG. Laboratory measured behavioral impulsivity relates to suicide attempt history. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2004;34:374–385. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.4.374.53738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erinoff L, Compton WM, Volkow ND. Drug abuse and suicidal behavior. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76S:S1–S2. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: Neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1642–1652. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Fry AF, Myerson K. Discounting of delayed rewards: A life-span comparison. Psychological Science. 1994;5:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J. A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:769–792. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J, McFadden E. Rate of temporal discounting decreases with amount of reward. Memory & Cognition. 1997;25:715–723. doi: 10.3758/bf03211314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth L. The role of impulsivity in the aetiology of drug dependence: reward sensitivity versus automaticity. Psychopharmacology. 2011;215:567–580. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2172-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckans M, Seelye A, Woodhouse J, Parcel T, Mull L, Schwartz D, et al. Discounting of delayed rewards and executive dysfunction in individuals infected with hepatitis C. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2011;33:176–186. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.499355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;77:129–146. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN. Bidding on the future: Evidence against normative discounting of delayed rewards. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1997;126:54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Maraković NN. Delay-discounting probabilistic rewards: Rates decrease as amount increase. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1996;3:100–104. doi: 10.3758/BF03210748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1999;128:78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May A. Rethinking impulsivity in suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2010;40:612–619. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.6.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysinska K, Heller T, De Leo D. Suicide and deliberate self-harm in personality disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2006;19:95–101. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000191498.69281.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampert KM, Pizzagalli DA. Delay discounting and future-directed thinking in anhedonic individuals. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2010;41:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Bickel WK, editors. Impulsivity: The behavioral and neurological science of discounting. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maser JD, Akiskal HS, Schettler P, Scheftner W, Mueller T, Endicott J, Solomon D, Clayton P. Can temperament identify affectively ill patients who engage in lethal or near-lethal suicidal behavior? A 14-year prospective study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2002;32:10–32. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.10.22183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur J. An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. In: Commons M, Mazur J, Nevin J, Rachlin H, editors. The Effect of Delay and of Intervening Events on Reinforcement Value. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1987. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr HL, O’Brien CP. New data from the Addiction Severity Index: Reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, Schmitz JM, Swann AC. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1783–1793. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monterosso JR, Ainslie G, Xu J, Cordova X, Domier CP, London ED. Frontoparietal cortical activity of methamphetamine-dependent and comparison subjects performing a delay discounting task. Human Brain Mapping. 2007;28:383–393. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. On inhibition/disinhibition in developmental psychopathology: Views from cognitive and personality psychology and working inhibition taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:220–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL, Madden GJ, Badger GJ, Bickel WK. Needle sharing in opioid-dependent outpatients: Psychological processes underlying risk. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;60:259–266. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GW, Farrell M, Bunting BP, Houston JE, Shevlin M. Patterns of polydrug use in Great Britain: Findings from a national household population survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;113:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Esposito-Smythers C. Attempted and completed suicide in adolescence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2006;2:237–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, Fleck DE, DelBello MP, Adler CM, Shear PK, McElroy SL, et al. Characterizing impulsivity in mania. Bipolar Disorders. 2009;11:41–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranger C, Ryan SR, Fu H, Landes RD, Jones BA, Bickel WK, Budney AJ. Delay discounting predicts adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. doi: 10.1037/a0026543. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Lijffijt M, Lane SD, Steinberg JL, Moeller G. Severity of bipolar disorder is associated with impairment of response inhibition. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;116:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heeringen C, Bijttebier S, Godfrin K. Suicidal brains: A review of functional and structural brain studies in association with suicidal behaviour. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35:688–698. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassileva J, Gonzalez R, Bechara A, Martin EM. Are all drug addicts impulsive? Effects of antisociality and extent of multidrug use on cognitive and motor impulsivity. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:3071–3076. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-Garcia A, Perez-Garcia M. Profile of executive deficits in cocaine and heroin polysubstance users: Common and differential effects on separate executive components. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:517–530. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0632-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Leland DS, Churan J, Paulus MP. Impaired time perception and motor timing in stimulant-dependent subjects. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]