Abstract

Introduction

Isolated intraspinal extradural tuberculous granuloma (IETG) without radiological evidence of vertebral involvement is uncommon, especially rare in cervical spine.

Materials and methods

We report a case of cervical IETG without bone involvement in a patient with neurological deficit. The patient suffered from progressive neurological dysfunction. MRI of cervical spine revealed an intraspinal extradural mass, and the spinal cord was edematous because of the compression. Thus C2–C4 laminectomy was performed and extradural mass was excised.

Results

The excised extradural mass was confirmed to be tuberculous granuloma through pathologic examination. Antituberculous drugs were administrated with a regular follow-up. Excellent clinical outcomes were achieved.

Conclusions

The isolated IETG, although a rare entity, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the intraspinal mass, especially in patients with spinal cord compression and a history of tuberculosis. If there is a progressing neurological deficit, a combination of surgical and anti-tuberculous treatment should be the optimal choice.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Intraspinal extradural tuberculous granuloma, Cervical

Introduction

Skeletal tuberculosis (TB) is the most frequent type of extra-pulmonary TB [1], and spinal TB comprises nearly 50% of the skeletal TB [2]. There is general agreement on the fact that intraspinal tuberculous lesions are mostly secondary to spinal TB [3]. Intraspinal extradural tuberculous granuloma (IETG) is a rare cause of spinal cord compression lesions, especially infrequent for isolated granuloma without vertebral involvement [4, 5]. Moreover, most cases of IETG in literatures only involved the thoracic or lumbar regions of spine, and cervical spine involvement was more uncommon. However, no study have explained the reasons for this rareness. Herein, we report an extremely rare case of isolated IETG in cervical spine and try to figure out the causes of this entity.

Case report

A 63-year-old male patient complained pain in the neck and upper thoracic regions for 6 months duration. He suffered from progressive weakness and slightly numbness in both hands and arms for 5 months, and with aggravation for about 2 weeks. He has no clear history of trauma or any contact with TB or HIV infection, and no exact symptom or sign of immune deficiency or any underlying malignancy.

The patient presented normal general physical condition, and normal body temperature. The physical examination revealed slightly tenderness in the upper thoracic region, insignificant hypesthesia, grade 4/5 muscular strength and normal muscle tone of the upper extremities, positive Hoffmann’s sign bilaterally. The sensation, muscle strength and muscle tone of lower extremities were normal. The patient reported no urinary or bowel dysfunction.

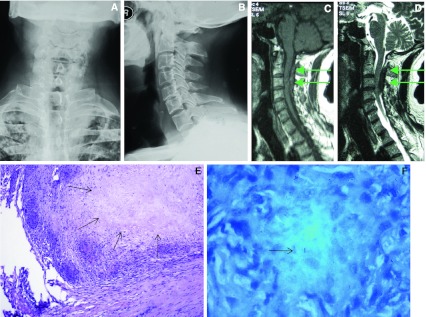

Routine laboratory examinations revealed hemoglobin, white blood cell count and C-reactive protein (CRP) were within normal range, but the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 33 mm/h, which is beyond the normal range (0–15 mm/h). Conventional radiograph of the chest revealed bilateral old pulmonary nodules in the upper lobes. The cervical spine X-ray film showed normal vertebral alignment, without evidence of vertebrae destruction (Fig. 1a, b). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of cervical spine revealed an intraspinal extradural mass with the spinal cord being compressed and edematous. Sagittal T2-weighted MR image revealed clearly a shuttle-like shape mass with low signal intensity extending from C2 to C4 in the posterior epidural space, yet no abnormal signal of posterior elements of the vertebrae was detected (Fig. 1c, d).

Fig. 1.

A 63-year-old male patient. Both the preoperative posterior-anterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs of cervical spine didn’t show any bone destruction. Preoperative sagittal T1-weighted (c) and T2-weighted MR images (d) of cervical spine revealed clearly a shuttle-like shape mass with low signal intensity extending from C2 to C4 in the posterior epidural space of the canal with the spinal cord being compressed and edematous (arrows). Postoperative pathological section (e) demonstrated granulomatous tissue with inflammatory cells and caseous necrosis (arrows in E, HE stain, ×100) and photomicrograph (f) showed positive tissue staining for acid-fast bacilli (arrow in f, acid-fast stain, ×1000)

Due to progressive neurological dysfunction, the patient underwent spinal cord decompression and excision of the mass through C2–C4 laminectomy. It was noted in the surgery that the posterior elements of cervical spine was intact and the mass was extradural, adhering to the spinal dura mater. The size of the mass was about 4 × 2 × 1 cm. Pathologic examination showed the appearance of a tuberculous granuloma in which caseous necrosis, epithelioid hystiocytes, Langhans’ type multinuclear giant cells, and chronic inflammatory cells were observed. The pathological section showed negative on Gram stains for bacteria, and mycobacterium tuberculosis was found in the specimen, with formation of caseous necrosis (Fig. 1e, f). Thus tuberculous granuloma was confirmed pathologically.

The standard antituberculous drugs were administrated with regular follow-up. At 1 year follow-up, the patient showed complete neurological recovery with muscle strength progressed to grade 5 of 5 and normal sensory function.

Discussion

Although TB has not seen as frequently as before, it still remains an important pathologic problem in developing countries [6]. Bone and joint TB may account for 15–35% of patients with extrapulmonary TB [7]. Spinal TB, traditionally referred to Pott’s disease, accounting for 25–60% of all osseous infections caused by tuberculosis [8, 9]. Most cases of spinal TB involved the thoracic and lumbar regions, and the cervical spine involved at a rate fewer than 5% [10]. Intraspinal TB, probably secondary tuberculous lesions, including intraspinal tuberculoma and tuberculous granuloma, was rarely reported [11].

The preoperative examinations of this case gave us an initial impression that it might be epidural mass. We proposed an epidural tumor, like tumor of nervous system, or hematologic system, or metastasis. Considering the elevated ESR, we also suspected an epidural abscess. And we questioned the possibility of TB, but we thought it was less likely, because a TB lesion with such an appearance, isolated in spinal canal without bony involvement, was rather rarely seen in cervical spine. Yet the pathological examination confirmed to be tuberculous granuloma eventually. In fact, there was radiographic evidence suggesting old pulmonary TB, which was underestimated in this case.

Isolated intraspinal TB without radiological evidence of vertebral involvement is rather uncommon. Kumar et al. [12] reported 22 patients with intraspinal TB, including 12 extradural granulomas, among them only 3 patients were found without osseous involvement, but none involved the cervical spine. Most cases of Intraspinal extradural tuberculous granuloma (IETG) reported in literatures involved the thoracic or lumbar regions of spine, but cervical spine involvement was very rare. To the best of our knowledge, only two similar cases of isolated IETG involved cervical spine without bone destruction had been reported. In 1981, Reichenthal et al. [5] reported a 70-year-old female with extraosseous IETG at the C7 level, which was proved by histological and bacteriological examination. Shah et al. [13] reported a 49-year-old female with IETG in the craniovertebral junction which extended from the upper cervical cord to the level of C5. However, our case was a male patient, with C2–C4 level involved, different from the two patients of the literatures with craniovertebral junction or lower cervical spine involved. The 3 cases indicate that IETG may involve any level of the cervical spine.

TB of posterior elements of spine is rare [14]. Among spinal TB, isolated intraspinal TB with absence of vertebral destruction and with neural deficit is less than 5%. The cause for spinal TB with posterior elements involved is that hematogenous spreading occurs via venous pathway [15]. The posterior external venous plexuses of vertebral veins anastomose freely with other vertebral venous plexuses and constitute the final pathway for infection to reach the neural arch in this atypical form of spinal TB [15]. Turgut [16] postulated that the infection originated from pelvic organs initially and then disseminated haematogenously to involve more superior areas of the spine. The above reasons could explain why cervical TB is so rare. Considering that intraspinal TB is secondary, the reasons for the rareness of TB involving posterior elements and the low incidence of TB in cervical spine, it can be understood why isolated IETG without vertebral involvement in cervical spine is so infrequent.

The clinical manifestation of IETG is usually nonspecific, but neurological deficit may occur with a rapid evolution [3]. The preoperative diagnosis of IETG is challenging because it has no specific clinical symptoms or radiologic findings, just as the intradural extramedullary spinal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor reported by Zemmoura et al. [17]. Thus doctors should consider the differential diagnosis when a case of intraspinal tumor syndrome of progressive neurological deficit is encountered, especially for a case with a history of TB [13]. A MRI scan is required to determine the level and the possible nature of the lesion though the final diagnosis can only be established by pathological examination. The MRI of our case revealed an intraspinal extradural mass with the spinal cord being compressed and edematous. Epidural tumor was considered initially, but tuberculous granuloma was confirmed pathologically.

Surgery remains the most effective treatment for IETG. A laminectomy is suitable for such extradural extraosseous granuloma. Nussbaum et al. [18] suggested that patients with epidural or subdural granulomatous tissue in the absence of significant bone collapse may be treated satisfactorily with simple laminectomy and debridement. Since extradural granuloma may jeopardize spinal cord function, Tureyen et al. [19] suggested that the optimal treatment for IETG include a combination of microsurgical resection and antitubercular chemotherapy. Usually the patient may have good neurological recovery after adequate surgical decompression and antitubercular therapy [20].

We first figured out the causes for the rareness of IETG. Due to the clinical and radiological non-specificity of IETG, it may be confused with intraspinal tumor, causing misdiagnosis clinically. Thus the significance of current report is to point out the importance of differential diagnosis when facing intraspinal mass. More importantly, the treatment of IETG is somewhat different from intraspinal tumor. Thus clinicians should not neglect the possibility of tuberculous granuloma when facing with intraspinal space-occupying disease, especially for those with a history of TB.

Conclusions

The isolated IETG, although a rare entity, should be considered in the differential diagnosis when facing a case of intraspinal tumor syndrome of progressive neurological deficits, especially in patients with a history of TB. For isolated IETG without vertebral involvement, and accompanied with a progressing neurological dysfunction, a combination of surgical decompression and antituberculous treatments should be the optimal choice, which may produce a good clinical outcome.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the pathological data of the patient provided by the Department of Pathology of our Hospital.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Davidson PT, Horowitz I (1970) Skeletal tuberculosis—A review with patient presentations and discussion. Am J Med 48:77 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Hsu LCS, Leong JCY. Tuberculosis of the lower cervical-spine (C2–C7)—A report on 40 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66:1–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.66B1.6693464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arseni C, Samitca DCT (1960) Intraspinal tuberculous granuloma. Brain 83:285 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Mantzoros CS, Brown PD, Dembry L. Extraosseous epidural tuberculoma—Case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:1032–1036. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.6.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichenthal E, Cohen ML, Shalit MN. Extraosseous extradural tuberculous granuloma of the cervical-spine—A case report and review of intraspinal granulomatous infections. Surg Neurol. 1981;15:178–181. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(81)90134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kayaoglu CR, Tuzun Y, Boga Z, Erdogan F, Gorguner M, Aydin IH. Intramedullary spinal tuberculoma—A case report. Spine. 2000;25:2265–2268. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200009010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies PDO, Humphries MJ, Byfield SP, Nunn AJ, Darbyshire JH, Citron KM, Fox W. Bone and joint tuberculosis—A survey of notifications in England and Wales. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66:326–330. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.66B3.6427232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harada Y, Tokuda O, Matsunaga N. Magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of tuberculous spondylitis versus. pyogenic spondylitis. Clin Imag. 2008;32:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tali ET. Spinal infections. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50:120–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajasekaran S, Shanmugasundaram TK, Prabhakar R, Dheenadhayalan J, Shetty AP, Shetty DK. Tuberculous lesions of the lumbosacral region—A 15-year follow-up of patients treated by ambulant chemotherapy. Spine. 1998;23:1163–1167. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199805150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watts HG, Lifeso RM. Tuberculosis of bones and joints. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78A:288–298. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199602000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar S, Jain AK, Dhammi IK, Aggarwal AN (2007) Treatment of intraspinal tuberculoma. Clin Orthop Relat R:62–66 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Shah A, Nadkarni T, Goel N, Goel A. Circumferential craniocervical extradural tuberculous granulations. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:808–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.07.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narlawar RS, Shah JR, Pimple MK, Patkar DP, Patankar T, Castillo M. Isolated tuberculosis of posterior elements of spine: magnetic resonance imaging findings in 33 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:275–281. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200202010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acharya S, Ratra GS. Posterior spinal cord compression—Outcome and results. Spine. 2006;31:E574–E578. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000229805.10506.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turgut M. Multifocal extensive spinal tuberculosis (Pott’s disease) involving cervical, thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. Brit J Neurosurg. 2001;15:142–146. doi: 10.1080/02688690120036856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zemmoura I, Hamlat A, Morandi X. Intradural extramedullary spinal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: case report and literature review. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(Suppl 2):S330–S335. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1783-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, Erickson DL, Seljeskog EL. Spinal tuberculosis—A diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243–247. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tureyen K. Tuberculoma of the conus medullaris: case report. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:651–652. doi: 10.1227/00006123-200203000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain AK. Tuberculosis of the spine-A fresh look at an old disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92B:905–913. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B7.24668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]