Abstract

Background

The pelvis is an infrequent site of osteosarcoma and treatment requires surgery plus systemic chemotherapy. Poor survival has been reported, but has not been confirmed previously by the Children’s Oncology Group (COG). In addition, survival of patients with pelvic osteosarcomas has not been compared directly with that of patients with nonpelvic disease treated on the same clinical trials.

Questions/purposes

First, we assessed the event-free (EFS) and overall survival (OS) of patients with pelvic osteosarcoma treated on COG clinical trials. We then asked whether patient survival compared with that of patients treated on the same clinical trials with nonpelvic disease. Finally, we asked whether patients with metastatic disease at initial diagnosis had worse survival.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed data from 1054 patients with osteosarcoma treated in four studies between 1993 and 2005. Twenty-six of the 1054 patients (2.5%) had a primary tumor of the pelvis. At diagnosis, nine patients had metastatic disease. The minimum followup was 2 months (mean, 34 months; range, 2–102 months).

Results

Two of the nine patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis and five of the 17 with localized disease were alive at last contact. Estimates of the 5-year EFS for localized versus metastatic disease of the pelvis were 22% versus 23%. OS for patients with localized versus metastatic disease was 47% versus 22%. Patients with osteosarcoma in all other locations had a 5-year EFS of 57% and OS of 69%.

Conclusions

Our analysis confirms poor survival for patients with pelvic osteosarcoma. Survival with metastatic disease in the absence of a pelvic primary tumor is similar to that for localized or metastatic pelvic osteosarcoma. Improved surgical or medical therapy is needed, and patients with pelvic osteosarcoma may warrant alternate or experimental therapy.

Level of Evidence

Level II, prognostic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Historically, the survival for patients with osteosarcoma was poor when treated with surgical resection followed by observation with a 6-year event-free survival (EFS) of 11% [11]. The addition of multiagent chemotherapy improved the 6-year EFS to 60% to 78% [5, 11, 14]. Effective therapy requires administration of chemotherapy plus local control. Surgical excision is the standard local control, although radiation has been used for local control mostly in patients who refuse surgery or whose tumors are deemed unresectable. However, the EFS for those patients remains poor compared with the EFS for patients undergoing surgical resection with a 5-year EFS less than 30% [8].

The pelvis is an infrequent site for osteosarcoma, reportedly accounting for only 5% of patients [18]. The management of pelvic osteosarcoma is challenging because it is difficult to achieve a complete surgical excision with adequate margins. This results in a rate of local recurrences ranging from 11% to 44% [2, 4, 6].

Some reports [2, 6, 10, 17, 19] of patients with pelvic osteosarcoma are from single institutions. Although these studies show overall survival (OS) rates ranging only from 19% to 47% [2, 6, 10, 17, 19], it is unclear whether this prognosis is universal for all patients or specific to those institutions. European and Asian cooperative groups reported 5-year OS of almost 30% [7, 13, 16]. In North America and across the globe, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) has been a leader in understanding and improving the outcome for childhood cancer. Providers worldwide rely on data reported from the COG to help guide therapy. Consequently, confirmation of cooperative group studies outside the COG is critical. In addition, improving our understanding of the prognosis of pelvic osteosarcoma in the context of the same treatment given to patients with osteosarcoma outside the pelvis will be important to the multidisciplinary providers who specialize in treating this rare tumor.

Therefore, we determined (1) the EFS and OS rates for patients with localized and metastatic pelvic osteosarcoma; (2) whether patients with unresected pelvic osteosarcoma have a similar survival to those with resected disease; and (3) whether the survival of patients with pelvic osteosarcoma is similar to that of patients treated for nonpelvic osteosarcoma.

Patients and Methods

We performed a cohort study, analyzing data from four clinical trials (INT-0133, CCG-7943, P9754, and AOST0121) conducted through the COG, Pediatric Oncology Group, and Children’s Cancer Group. These studies were open consecutively between 1993 and 2005. Data were compiled by assessing case report forms submitted from individual participating member institutions of the COG. CCG-7943 and AOST0121 were open only for enrollment of patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis. INT-0133 was open for the enrollment of patients with nonmetastatic disease from institutions affiliated with either the Children’s Cancer Group or the Pediatric Oncology Group; patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis from institutions affiliated with the Children’s Cancer Group also could be enrolled. P9754 was open for only the enrollment of patients with nonmetastatic disease at diagnosis from institutions affiliated with either the Children’s Cancer Group or Pediatric Oncology Group.

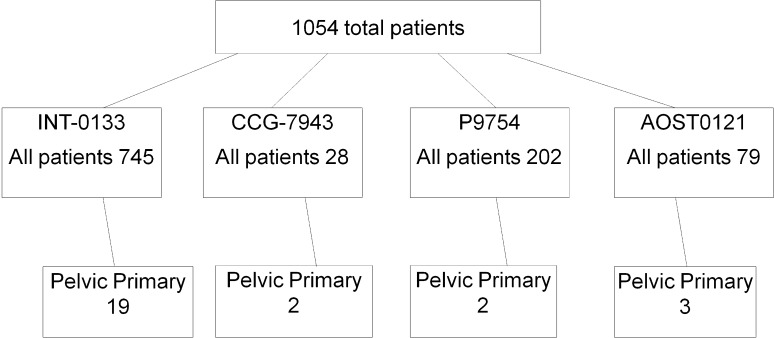

Among the 1054 patients with newly diagnosed osteosarcoma treated in the four cooperative group studies, 26 patients (2.5%) had a primary tumor involving the pelvis (Fig. 1). The minimum followup for patients who had not experienced an EFS event was 0.21 year (mean, 3.3 years; range, 0.21–8.53 years). This included six of 26 patients who were alive at last contact with no evidence of disease. One of the 26 patients was lost to followup before definitive surgery. All data were obtained from case report forms collected during the time that the clinical trials were open and no followup data could be accessed after study closure. The minimum followup was 2 months (mean, 34 months; range, 2–102 months).

Fig. 1.

The distribution of patients with pelvic osteosarcoma is shown among four clinical trials conducted through the COG between 1993 and 2005.

At study entry, patients were required to have a pathologic diagnosis of high-grade osteosarcoma. Open biopsy was preferred, but not required to enroll in the four studies. Imaging before study entry included radiographs and CT scan or MRI of the primary tumor. Staging studies at diagnosis included a bone scan and CT scan of the chest. Characteristics of the preoperative tumor that were reported on the case report forms varied in the different studies; INT0031 included tumor location options (ilium, ischium, sacrum), and CCG-7934 and P9754 asked for location and resection type, but did not require margin status information. In addition, although AOST0121 asked for information regarding tumor location, the forms did not request information regarding surgery, including no request for margin status. Degree of involvement or location in each bone was not specified on the case report forms. After study completion, followups were performed every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months for 2 years, and once at 5 years. At each visit, imaging included radiographs and CT or MRI of the primary tumor and CT of chest. The median age of the patients at the time of enrollment was 16 years (range, 9–26 years). Twelve patients were male and 14 were female. Eighteen patients had tumors located in the ilium, four had tumors in the sacrum, and one patient had involvement of the ilium and sacrum. At the time of diagnosis, nine patients had metastatic disease (six to the lung only, two to bone only, and one to the lung and bone), assessed by CT scan. Maximum tumor dimension at enrollment was available for 10 patients and was assessed by CT scan (median, 12.0 cm; range, 6.5–19.5 cm).

Details regarding protocol therapy have been published [14, 20]. Patients enrolled in INT-0133 included those without clinically detectable metastatic disease and whose disease was considered resectable. They received methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin chemotherapy and were randomly assigned to receive or not receive ifosfamide and/or muramyl tripeptide in a two-by-two factorial design. Patients with nonmetastatic disease who were treated in P9754 received response-based therapy with good responders (≥ 98% necrosis postinduction) given methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin or methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin plus ifosfamide and dexrazoxane with each doxorubicin dose. Standard responders (< 98% necrosis postinduction) received one of three pilots designed to evaluate augmentation with doxorubicin or ifosfamide and etoposide. CCG-7943 included only patients with metastatic disease and evaluated an upfront window of topotecan (daily ×5) followed by ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide alternating with cisplatin, and doxorubicin. (For a summary of the protocol therapy for AOST0121, see www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/COG-AOST0121.) Briefly, AOST0121 involved a standard backbone of chemotherapy used for patients with metastatic disease. This included methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in combination with ifosfamide and etoposide. Trastuzumab was added for patients noted to have HER2 positivity.

Data regarding surgical resectability were available for 18 of the 26 patients, whereas eight patients had no surgical data reported. The eight patients without surgical data remained in the study and are included in the survival estimates. Of the 18 patients with resectability data, 11 had an attempted surgery, three had tumors deemed unresectable, two had progressive disease before planned surgery, and two refused surgery. Of the 11 patients who had an attempted surgical resection, six patients had R1 margins (microscopic positive margins) and five had R0 margins (no tumor at margin). Data regarding the type of reconstruction were available for four patients: one osteoarticular allograft, two allograft arthrodeses, and one allograft and prosthesis composite (Table 1). No patients received radiation therapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 26 patients with pelvic osteosarcoma treated on Children’s Oncology Group clinical trials

| Study | Sex | Age (years) | Primary site | Maximum diameter (mm) | Metastasis (site) | Margin | Resection type | Outcome (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCG-7943 | Male | 14 | Pelvis NOS | NR | Yes (L, B) | NR | Nonresectable | DOD (1.4) |

| CCG-7943 | Female | 17 | Ilium | NR | Yes (L) | NR | NR | DOD (0.8) |

| INT-0133 | Female | 9 | Ilium | 150 | No | Positive | Osteoarticular, extraarticular | Alive (8.4) |

| INT-0133 | Female | 10 | Pelvis NOS | 120 | No | Positive | Hemipelvectomy | DOD (5.5) |

| INT-0133 | Female | 12 | Ilium | 65 | No | Positive | NR | DOD (2.7) |

| INT-0133 | Female | 12 | Vertebra-sacral | NR | No | NR | Nonresectable | Alive (1.4) |

| INT-0133 | Female | 12 | Ilium | 180 | No | Clear | Osteoarticular, extraarticular | Alive (3.4) |

| INT-0133 | Female | 13 | Ilium | 120 | No | Clear | Hemipelvectomy | Alive-SMN (6.2) |

| INT-0133 | Female | 15 | Ilium | 115 | No | Clear | Osteoarticular, extraarticular | DOD (1.9) |

| INT-0133 | Female | 16 | Ilium | NR | No | NR | Progressive disease before planned resection | DOD (0.7) |

| INT-0133 | Female | 19 | Vertebra-sacral | NR | No | NR | Patient refused surgery | DOD (1.0) |

| INT-0133 | Female | 19 | Ilium | NR | Yes (L) | NR | Progressive disease before planned resection | DOD (0.7) |

| INT-0133 | Female | 23 | Ilium | 83 | No | Positive | Osteoarticular, extraarticular | DOD (5.6) |

| INT-0133 | Male | 12 | Vertebra-sacral | NR | No | NR | Nonresectable | DOD (0.9) |

| INT-0133 | Male | 16 | Ilium | 195 | Yes (L) | Positive | Hemipelvectomy | DOD (1.4) |

| INT-0133 | Male | 16 | Ilium | 95 | Yes (L) | Clear | Osteoarticular, extraarticular | Alive (8.5) |

| INT-0133 | Male | 16 | Ilium | 150 | No | NR | Osteoarticular, extraarticular | DOD (6.0) |

| INT-0133 | Male | 17 | Pelvis NOS | NR | No | Positive | Hemipelvectomy | DOD (3.3) |

| INT-0133 | Male | 18 | Ilium | NR | No | NR | NR (lost to followup) | Alive (0.2) |

| INT-0133 | Male | 18 | Ilium | NR | Yes (B) | NR | Patient refused surgery | DOD (1.8) |

| INT-0133 | Male | 20 | Ilium | NR | No | NR | NR | DOD (2.1) |

| P9754 | Male | 13 | Ilium | NR | No | Clear | Intercalary, through growth plate | DOD (5.7) |

| P9754 | Male | 26 | Ilium-sacrum | NR | No | NR | NR | DOD (0.9) |

| AOST0121 | Female | 15 | Ilium | NR | Yes (L) | NR | NR | Alive (2.9) |

| AOST0121 | Female | 17 | Sacrum | NR | Yes (B) | NR | NR | DOD (0.5) |

| AOST0121 | Male | 16 | Ilium | NR | Yes (L) | NR | NR | DOD (0.8) |

NOS = not otherwise specified; NR = not reported; L = lung; B = bone; DOD = dead of disease; SMN = secondary malignant neoplasm.

EFS was taken to be the time from enrollment on the relevant protocol until disease progression, diagnosis of a second malignant neoplasm, death, or last patient contact, whichever occurred first. A patient who experienced disease progression, second malignant neoplasm, or death was considered to have experienced an EFS event; otherwise, the patient was considered as censored at last contact. OS was taken to be the time from enrollment in the relevant protocol to death or last patient contact, whichever occurred first. A patient who died was considered to have experienced a death event; otherwise, the patient was considered as censored at last contact. We estimated OS and EFS using the method of Kaplan and Meier [9]. The risk for an EFS event and death was compared between patients with localized and metastatic disease using the log-rank test [9]. We performed the analyses in SAS® 9.2 using PROC LIFETEST and PROC PHREG (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

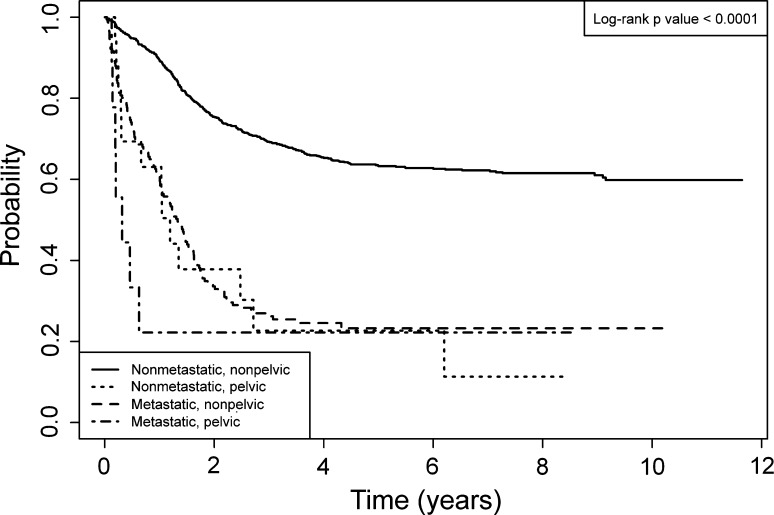

The 5-year EFS for localized versus metastatic disease of the pelvis were similar (p = 0.379), 22% versus 23% respectively, with a hazard ratio for an EFS event in patients with localized disease of 0.66. The 5-year estimates of OS for patients with localized versus metastatic disease also were similar (p = 0.214), 48% versus 22%, with a hazard ratio for death for patients with localized disease of 0.55. The 5-year estimates of EFS and OS for the whole group were 23% and 38%, respectively (Fig. 2). Nineteen of the 26 total patients had disease progression or recurrence at a median of 0.32 years after diagnosis (range, 0.13–2.72 years). All 19 of these patients died. Two of the nine patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis and five of the 17 with localized disease were alive at last contact.

Fig. 2.

Twenty-six patients with pelvic osteosarcoma were analyzed from 1993 to 2005. The 5-year event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) for the total cohort were poor at 23% and 38% respectively (EFS CI, 9%–41%; OS CI, 20%–57%).

Survival appears to be better for patients who were reported to have a complete resection of the pelvic tumor. We found that of the 18 patients with surgical data reported, 13 either did not have resection or had positive margins. Only two of the 13 patients were alive at last contact. However, five of 18 patients with surgical data reported had a complete resection and three of those patients were alive at last contact.

Survival of patients with osteosarcoma of the pelvis was worse than the survival of patients treated on the same protocols with osteosarcoma not located in the pelvis. Patients with osteosarcoma in nonpelvic locations had a greater (p < 0.001) 5-year EFS of 57% as compared with the EFS of patients with osteosarcoma of the pelvis (Fig. 3). In addition, the 5-year OS of patients with nonpelvic osteosarcoma was superior at 69% (p < 0.001) when compared with the OS of patients with osteosarcoma of the pelvis. The percentage of patients with pelvic osteosarcoma who had metastatic disease at presentation was greater (p = 0.025) than for patients with primary tumors of any other site: 35% versus 16%, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Event-free survival (EFS) as a function of time since study enrollment for patients with pelvic and nonpelvic osteosarcoma is shown. Patients with localized or metastatic pelvic osteosarcoma had similar 5-year EFS as patients with nonpelvic metastatic osteosarcoma. The 5-year EFS for each cohort were: localized pelvic osteosarcoma 23% (CI, 6%–46%); metastatic pelvic osteosarcoma 22% (CI, 3%–51%); localized nonpelvic osteosarcoma 63% (CI, 60%–66%); and metastatic nonpelvic osteosarcoma 23% (CI, 17%–30%).

Discussion

Therapeutic advances in the treatment of high-grade osteosarcoma have led to great improvements in OS and EFS. The ability to undergo a complete surgical resection is critical, and patients unable to undergo a complete resection or who have positive margins are at greater risk for relapse or death [2, 3]. As a leader in the improvement of therapy delivered to patients with osteosarcoma, the COG has been at the forefront of conducting clinical trials in this disease. However, the subset of patients with localized and metastatic pelvic disease had not been formally analyzed or compared with patients with nonpelvic disease. Therefore, we determined (1) the EFS and OS rates for patients with localized and metastatic pelvic osteosarcoma; (2) whether patients with unresected pelvic osteosarcoma have a similar survival as that for patients with resected disease; and (3) whether the survival of patients with pelvic osteosarcoma compares with survival for patients treated for osteosarcoma not located in the pelvis.

We recognize limitations of our study. First, the number of patients with pelvic osteosarcoma treated on the COG clinical trials is small. This is partly attributable to the rarity of involvement of this region of the body. However, investigator bias may play a role, including the belief that patients with pelvic tumors will not do well with the standard chemotherapy used as the backbone of the clinical trials. Despite the rarity, this cohort is based on a sampling of patients from across the country and we believe is a fair representation of patients who are diagnosed with this disease. Second, eligibility criteria often excluded patients from study who were deemed to have unresectable tumors at diagnosis by the enrolling institution. Thus, although many patients did turn out to have unresectable disease and were enrolled, there may be some patients not offered enrollment at diagnosis based on the extent of disease. Third, the design of the clinical trials did not foresee that questions regarding pelvic location of disease would be asked. Therefore, the studies were not originally designed to later answer survival questions regarding this population. To do so, it was necessary to retrospectively analyze this cohort of patients. Although, we do believe the data are valid, there may be biases created by the retrospective design of this study. Finally, we are limited in our ability to analyze the surgical data for the patients in this study. The clinical trials were conducted across North America with more than 150 institutions participating. The data analyzed are gleaned from the case report forms provided during the time that the clinical trials were open. In some cases, the forms did not request specific information regarding the surgery and in other cases the forms only requested whether a complete resection was achieved, but not the details of surgery type. Despite this, the majority of forms was complete and provided enough data to compile important information regarding this cohort of patients.

We found that the 5-year estimates of EFS and OS for the whole cohort were 23% and 38%. Although we did not find a difference in EFS for patients with localized versus metastatic disease, the survival for patients with a complete resection appears better than for patients who have no resection or positive margins. Of the 17 patients with localized disease at diagnosis, only four had a clear margin at surgery and two of these four patients were alive at last followup. However, of the nine patients who had metastatic disease at diagnosis, only two were alive at last followup, and only one of these two patients had a clear margin. Although these numbers are small, they are consistent with the typical EFS seen in patients with localized disease or metastatic disease involving all other sites of disease when there is a complete resection [14]. Others have reported similar results for patients with pelvic osteosarcoma [4, 10, 16, 19]. However, a few key differences exist between our cohort and the majority of patients in studies reported in the literature (Table 2). The first is that other studies typically involve older cohorts and are more representative of an adult patient population. The second is that other studies typically have reviewed patients over long periods in which surgical technique may have changed or supportive care effecting OS could be influential. Additionally, multiple studies are single-institution cohorts, which may not be representative of the broad base of patients seen across the country and operated on by various surgeons. In 1998, Kawai et al. [10] reported a cohort of 40 patients with pelvic osteosarcoma with a median age of 25 years and range up to 76 years old. The 5-year OS for the whole group was 34%, with a 10% 5-year survival for patients with unresectable tumors and 41% 5-year survival for patients with resections [10]. More recently, Fuchs et al. [4] reported the OS for patients with pelvic osteosarcoma treated during a 20-year period. In their cohort, the mean age was 34 years with an upper limit of 66 years They found that 13 of 30 patients did not have an adequate tumor-free margin and the 5-year OS was only 38% [4]. The European Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group had similar results [16]. The study had 67 patients with a median age of 20 years and range up to 63 years, during a 20-year period, with an osteosarcoma of the pelvis. Of these, 50 underwent surgical resection: 38 limb-sparing and 12 hemipelvectomies. Fifty percent of patients who had resections had positive residual disease. The overall 5-year survival was only 27% [16]. Although their study involved a 35-year period, the single-institution report by Saab et al. [19] in 2005 includes data most similar to ours. They reported 19 patients with pelvic disease and found only nine had resectable disease. The average age of their patients was 16 years with an upper age of 28 years. The 5- and 10-year OS for their patients were 26.3% and 19.7%, respectively [19].

Table 2.

Comparison of pelvic osteosarcoma data reported in the literature

| Study | Number of patients | Multiinstitution | Period analyzed | Age range of patients (years) (median) | Mean time to followup | % with metastases (number) | % completely resected (number) | Overall survival (5-year) | Overall survival of nonpelvic sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saab et al. [19] | 19 | No | 1970–2004 | 10.8–28.7 (16.8) | NR | 26 (5) | 26 (5) | 26% | NR |

| Kawai et al. [10] | 40 | No | 1977–1994 | 13–76 (25) | NR | 20 (8) | 16 (40) | 34% | NR |

| Fuchs et al. [4] | 43 | No | 1983–2003 | 11–66 (mean, 34.4) | 3.5 years | 14 (6) | 70 (30) | 38% | NR |

| Ozaki et al. [16] | 67 | Yes | 1979–1998 | 10–63 (20) | 6.5 years | 22 (15) | 37 (25) | 27% | NR |

| Current study | 26 | Yes | 1993–2005 | 9–26 (16) | 3.3 years | 34 (9) | 19 (5) | 38% | 0.69 |

NR = not reported.

Our analysis suggests patients with pelvic osteosarcoma (local or metastatic) have a survival similar to that for patients with nonpelvic metastatic disease and suggest these patients should be included in studies of innovative new strategies or new agents. This would allow these patients the potential to receive novel treatment approaches and allow us to prospectively evaluate treatment results for a subset of patients who currently are not evaluated in a consistent fashion. Additionally, it is notable that three of the five patients who underwent a complete resection did not have a recurrence during the time of data collection. Alternate therapies, including the use of standard external beam or proton radiation therapy, could be considered for patients with tumors that are not completely resected. This modality may be best suited for patients with gross total resections, although radiation therapy could be considered for patients with unresectable disease [1]. In addition, samarium-153 reportedly decreases pain and responses to therapy have been documented by PET-CT scans [12]. However, improvements in progression-free survival have not been seen with this modality and ideally would be assessed in a large number of patients with unresectable disease. With a lack of randomized trials assessing these modalities in patients with unresectable osteosarcoma, we cannot make a definitive recommendation regarding use in patients with unresected disease.

We found that although patients with primary tumors of the pelvis and metastatic disease had a similar outcome as patients with nonpelvic primary disease and metastatic disease, the patients with localized disease of the pelvis did far worse than those with nonpelvic, localized disease. We attribute much of the poor outcome to the large size and inability to obtain an adequate surgical resection for these patients. In our series, only 10 patients had their tumor size reported, although it is notable that the median size of 12 cm in diameter was quite large compared with reports in which lesions were primarily nonpelvic [15]. In addition, we found a higher proportion of patients with metastatic disease with a pelvic primary disease than patients with nonpelvic primary sites, raising the possibility that patients with pelvic tumors have more aggressive lesions or symptoms may manifest more slowly in tumors occurring in the pelvis. Biology also may play a role, although this is conjecture and needs further evaluation.

Our analysis confirms the poor prognosis for patients with osteosarcoma involving the pelvis. We also observed that patients with pelvic disease fare worse than patients with osteosarcoma in all other locations treated on the same clinical trials. Improvements in surgical technique may lead to improvement in prognosis, although many patients still will not have tumors that can be resected. Improved surgical or medical therapy is needed, and patients with pelvic osteosarcoma may warrant alternate or experimental therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following collaborating members of the Children’s Oncology Group who have given us guidance during the analysis and writing of this manuscript, including Neyssa Marina MD, Paul Meyers MD, Nita Seibel MD, Cindy Schwartz MD, and Mark Krailo PhD. Among the institutions of The Children’s Oncology, over 150 had these trials open and contributed to the total enrolled on the four successive clinical trials and over 20 had patients with pelvic osteosarcoma.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Chair’s Grant U10 CA98543 and Human Specimen Banking Grant U24 CA114766 of the Children’s Oncology Group from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA. Additional support for research is provided by a grant from the WWWW (QuadW) Foundation, Inc (www.QuadW.org) to the Children’s Oncology Group.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

The analysis of data was performed primarily at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, CT, USA and is a report of the Children’s Oncology Group (COG).

References

- 1.DeLaney TF, Park L, Goldberg SI, Hug EB, Liebsch NJ, Munzenrider JE, Suit HD. Radiotherapy for local control of osteosarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:492–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donati D, Giacomini S, Gozzi E, Ferrari S, Sangiorgi L, Tienghi A, DeGroot H, Bertoni F, Bacchini P, Bacci G, Mercuri M. Osteosarcoma of the pelvis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson WS, Harris MB, Goorin AM, Gebhardt MC, Link MP, Shochat SJ, Siegal GP, Devidas M, Grier HE. Presurgical window of carboplatin and surgery and multidrug chemotherapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed metastatic or unresectable osteosarcoma: Pediatric Oncology Group Trial. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs B, Hoekzema N, Larson DR, Inwards CY, Sim FH. Osteosarcoma of the pelvis: outcome analysis of surgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:510–518. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0495-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goorin AM, Schwartzentruber DJ, Devidas M, Gebhardt MC, Ayala AG, Harris MB, Helman LJ, Grier HE. Pediatric Oncology Group. Presurgical chemotherapy compared with immediate surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy for nonmetastatic osteosarcoma: Pediatric Oncology Group Study POG-8651. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1574–1580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimer RJ, Carter SR, Tillman RM, Spooner D, Mangham DC, Kabukcuoglu Y. Osteosarcoma of the pelvis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:796–802. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B5.9241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ham SJ, Kroon HM, Koops HS, Hoekstra HJ. Osteosarcoma of the pelvis: oncological results of 40 patients registered by The Netherlands Committee on Bone Tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:53–60. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaffe N, Carrasco H, Raymond K, Ayala A, Eftekhari F. Can cure in patients with osteosarcoma be achieved exclusively with chemotherapy and abrogation of surgery? Cancer. 2002;95:2202–2210. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalbfleisch J, Prentice R. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. 2. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawai A, Huvos AG, Meyers PA, Healey JH. Osteosarcoma of the pelvis: oncologic results of 40 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;348:196–207. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199803000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Link MP, Goorin AM, Horowitz M, Meyer WH, Belasco J, Baker A, Ayala A, Shuster J. Adjuvant chemotherapy of high-grade osteosarcoma of the extremity: updated results of the Multi-Institutional Osteosarcoma Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;270:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahajan A, Woo SY, Kornguth DG, Hughes D, Huh W, Chang EL, Herzog CE, Pelloski CE, Anderson P. Multimodality treatment of osteosarcoma: radiation in a high-risk cohort. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:976–982. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuo T, Sugita T, Sato K, Hotta T, Tsuchiya H, Shimose S, Kubo T, Ochi M. Clinical outcomes of 54 pelvic osteosarcomas registered by Japanese musculoskeletal oncology group. Oncology. 2005;68:375–381. doi: 10.1159/000086978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyers PA, Schwartz CL, Krailo M, Kleinerman ES, Betcher D, Bernstein ML, Conrad E, Ferguson W, Gebhardt M, Goorin AM, Harris MB, Healey J, Huvos A, Link M, Montebello J, Nadel H, Nieder M, Sato J, Siegal G, Weiner M, Wells R, Wold L, Womer R, Grier H. Osteosarcoma: a randomized, prospective trial of the addition of ifosfamide and/or muramyl tripeptide to cisplatin, doxorubicin, and high-dose methotrexate. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2004–2011. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyers PA, Schwartz CL, Krailo MD, Healey JH, Bernstein ML, Betcher D, Ferguson WS, Gebhardt MC, Goorin AM, Harris M, Kleinerman E, Link MP, Nadel H, Nieder M, Siegal GP, Weiner MA, Wells RJ, Womer RB, Grier HE. Osteosarcoma: the addition of muramyl tripeptide to chemotherapy improves overall survival. A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:633–638. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.14.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozaki T, Flege S, Kevric M, Lindner N, Maas R, Delling G, Schwarz R, Hochstetter AR, Salzer-Kuntschik M, Berdel WE, Jurgens H, Exner GU, Reichardt P, Mayer-Steinacker R, Ewerbeck V, Kotz R, Winkelmann W, Bielack SS. Osteosarcoma of the pelvis: experience of the Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:334–341. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renard AJ, Veth RP, Schreuder HW, Pruszczynski M, Bokkerink JP, Hoesel QG, Staak FJ. Osteosarcoma: oncologic and functional results. A single institutional report covering 22 years. J Surg Oncol. 1999;72:124–129. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199911)72:3<124::AID-JSO3>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ries L, Eisner M, Kosary C, Hankey B, Miller B, Clegg L, Mariotto A, Feuer E, Edwards B. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2001, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD; 2004. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2001/. Accessed December 21, 2011.

- 19.Saab R, Rao BN, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Billups CA, Fortenberry TN, Daw NC. Osteosarcoma of the pelvis in children and young adults: the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience. Cancer. 2005;103:1468–1474. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seibel N, Krailo M, Chen Z, Healey J, Breitfeld P, Drachtman R, Greffe B, Nachman J, Nadel H, Sato J, Meyers P, Reaman G. Upfront window trial of topotecan in previously untreated children and adolescents with poor prognosis metastatic osteosarcoma: Children’s Cancer Group (CCG) 7943. Cancer. 2007;109:1646–1653. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]