Abstract

Background

Knowledge about factors leading to failure of posterior dynamic stabilization implants is essential to design future implants and establish surgical indications. Therefore, we analyzed an implant for single-level or hybrid configuration (adjacent to spondylodesis), which was recalled due to high failure rates.

Questions/purposes

We asked: (1) Were postoperative radiographic changes linked to implant failure? (2) Were radiographic parameters different between the two configurations? And (3) was implant failure related to inferior clinical scores?

Methods

The implant was used in 18 patients with lumbar single-level spinal stenosis or with (recurrent) disc herniation and concurrent degenerative disc disease and in 22 patients with an initially degenerated segment adjacent and superior to a fusion site. We prospectively obtained preoperative and postoperative (immediate, 6-, 12- and 24-month) clinical and radiographic evaluations; 37 of the 40 patients completed the 24-month followup. Using plain and extension-flexion radiographs, we compared implant failure rates and their association with postoperative implant translation, anterior and posterior disc height, and ROM for each configuration and between configurations. We assessed associations between clinical scores (VAS pain scores for back and leg, Oswestry Disability Index) and implant failure.

Results

Implant failure occurred in 10 of the 37 implants and corresponded to greater posterior disc height (single-level only) and implant translation. Adjacent-segment ROM increases and posterior disc height decreases over time were greater with the hybrid configuration. Implant failure rate related to higher Oswestry Disability Index (single-level only) and higher back pain scores.

Conclusions

Implant translation is associated with failure likely due to insufficient resistance to shear forces. Load transfer may cause progressive degeneration in the dynamic and adjacent segments, especially in the hybrid configuration.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Adjacent-segment degeneration (ASD) is one of the major problems in lumbar spinal fusion and may result in a need for reoperation [5, 21, 33, 38]. Although the development of ASD can be considered part of the normal aging and degenerative process, this phenomenon appears to be at least partly influenced by the altered stresses resulting from circumferential fusion [12, 31, 42]. Increased ROM and intradiscal pressure in the adjacent segment [6, 12, 15, 17, 22] may lead to progressive disc degeneration [28, 32] and facet joint arthritis [46].

Posterior dynamic stabilization devices were developed as an alternative treatment to fusion for lumbar degenerative diseases to restore functional stability while preserving segmental motion [49]. The concept of these devices is to reduce the load and restrict the motion of the affected level to stop or delay its degeneration. Forces acting adjacent to the construct increase to a lesser extent than they would with a fusion, thus reducing the risk of ASD. Various pedicle screw-based implant concepts are available for dynamic stabilization alone or as an adjunct to fusion in the lumbar spine (hybrid construct) [1]. In clinical use, studies have reported variable clinical improvement (0- to 100-mm VAS pain score, 15–60 mm; Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire [ODI] [9], 10%–58%) and failure rates (0%–41%) depending on the clinical indication [2, 3, 7, 14, 16, 18, 19, 25, 26, 34–37, 43, 44, 48, 50, 51]. Nevertheless, it remains unclear which material- or design-related factors are crucial for the success of a posterior-stabilizing system in clinical use [45].

The CD Horizon® Agile™ Spinal System (Medtronic, Memphis, TN, USA) was launched in 2007 for single-level (SL) dynamic stabilization or as a so-called topping-off hybrid construct (TO) adjacent and superior to spondylodesis. We were the first center to begin a multicenter observational study for both configurations to determine the safety and efficacy of this new implant. The original study was intended to determine whether the use of the implant was safe and feasible and effective regarding prevention of degeneration of the treated and adjacent segments, implant-associated complications, and improvement in clinical scores (VAS pain score, ODI). However, we terminated the study in December 2007 because of the recall of the implant due to high failure rates but followed the patients with the original study protocol over the planned study period. The design flaws were not clear at the time of the study but are important to identify for future application of posterior dynamic implants and enhancements of implant designs.

Therefore, we determined (1) the complication rate for the SL and TO implant configurations and which postoperative radiographic parameters were linked to implant failure; (2) whether the changes in the radiographic parameters were different between the two configurations; and (3) whether implant failure or configuration was associated with inferior clinical scores.

Patients and Methods

We prospectively enrolled 40 (SL: 18; TO: 22) patients in our observational study from July to December 2007. The clinical symptoms leading to operation were persistent back and (radicular or nonradicular) leg pain (65% SL, 100% TO), intermittent claudication (41% SL, 70% TO), and sensomotoric deficits (29% SL, 40% TO). Inclusion criteria for using the CD Horizon® Agile™ Spinal System (SL group) were symptomatic single-level spinal stenosis and/or recurrent or intraforaminal nucleus pulposus prolapse with degenerative disc disease (DDD) Modic Grade 1 [29] and/or facet joint arthritis of Fujiwara Grade 2 [10] (detected with MRI). Inclusion criteria for using the TO variant of the Agile™ system were DDD Modic Grade 2 or higher in one or more segments between L2 and S1 and single-level DDD Modic Grade 1 and/or facet joint arthritis of Fujiwara Grade 2 at the superior level adjacent to the higher degenerated segment(s). Patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis, up to Meyerding Grade II [27], and/or spinal stenosis in one or more of the higher degenerated levels were not excluded. Exclusion criteria for both groups were previous operations on the lumbar spine (except sequestrectomy or decompression); destructive processes; patients on long-term medication with corticoids or NSAIDs; patients with somatoform/psychosomatic pain of Grade II or higher according to Gerbershagen et al. [11]; patients with osteoporosis, kidney or liver diseases, malignant tumors, or a BMI of greater than 30 kg/m2; pregnancy; and chronic nicotine, alcohol, or drug abuse. Patients with DDD or facet joint arthritis in more than one segment and patients with spondylolisthesis in the affected level were excluded from the SL group or allocated to the TO group if possible. In the SL group, at the 12-month followup, we lost one patient who relocated. In the TO group, we lost one patient who underwent THA 9 months after the spine surgery and one patient who withdrew consent to participate in the study at the 24-month followup. The data of the three lost patients were excluded. All patients signed a patient consent form. An international ethics committee approved the original study (IRB/IEC Number 07/1763).

A power analysis had been performed for the original study based on improvement of ODI and VAS pain score. Because of the termination of that study due to the recall of the implant, the group size planned was not reached. The present analysis was therefore based on the radiographic and clinical parameters of the patients who were enrolled until the recall with inadequate power to address the original questions.

Age and sex were similar between the SL and TO groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics and operated levels

| Variable | SL group | TO group | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients† (enrolled patients) | 17 (18) | 20 (22) | |

| Age (years)‡ | 54.3 (46.7–61.9) | 63.8 (58.1–69.5) | 0.134 |

| Sex (male/female) | 12/5 | 8/12 | 0.054 |

| Level of dynamic stabilization (number of patients) | |||

| L5/S1 | 4 | 0 | |

| L4/5 | 9 | 9 | |

| L3/4 | 3 | 7 | |

| L2/3 | 1 | 3 | |

| L1/2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Number of fused levels (mono-/bi-/trisegmental) | 15/3/2 | ||

* p values are from two-sided unpaired t-test for comparison of age and from Fisher’s exact test for comparison of sex; †number of patients with complete 2-year followup; ‡values are expressed as mean, with 95% CI in parentheses; SL = single-level; TO = topping-off.

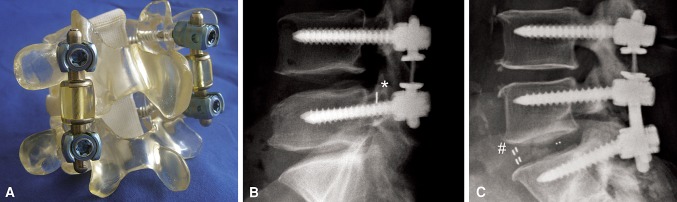

Surgery was performed by one of three surgeons (EH, MP, CG), employing a standard medial posterior approach. Polyaxial pedicle screws (Legacy™; Medtronic) were positioned under image intensifier control and by preservation of the facet joints in the affected levels (Table 1). Interlaminar decompression or sequestrectomy was performed by partial medial facetectomy and lateral recess decompression either unilaterally or bilaterally, according to patient symptoms, in all segments with spinal stenosis or nucleus prolapse. In the SL group, the device was positioned bilaterally between the pedicle screws and fixed under control of the polyaxial screw heads with the adjustment screws. The implant consists of a preassembled titanium rod with an integrated polycarbonate-urethane spacer. The spacer is connected to the rod with a floating titanium alloy cable and a load-bearing flange on each side (Fig. 1). Two fixed spacer sizes were available (10 and 15 mm), which were adapted to the individual segment height. In the TO group, fusion in the higher degenerated segments was performed either with the posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) technique with polyetheretherketone (PEEK) cages and additional posterior spondylodesis or with the latter alone employing autogenous corticocancellous bone obtained through the decompression and decortication of the facet joints and laminae in the fusion area. The SL and the TO variant of the implant have the same design at the dynamic part, while the distal rod of the TO configuration is of variable length, bridging the segments to be fused (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1A–C.

Images illustrate the CD Horizon® Agile™ implant. (A) An SL configuration of the implant is shown mounted to a Sawbones® model. (B) A lateral radiograph shows the SL configuration in a patient after previously performed sequestrectomy, indicated by a clip (*). (C) A lateral radiograph shows a patient with the TO configuration of the implant in combination with single-level PLIF (# indicates markers in the PEEK cages).

All patients were mobilized without an orthosis and given supervised pain-adapted physiotherapy (walking assists, isometric strengthening, proprioceptive training) for 2 to 4 hours per day during hospitalization, from the first postoperative day onward. After hospitalization, physiotherapy was continued (90 minutes, three to four times per week for 6–8 weeks).

For the original study, each patient was clinically and radiographically examined preoperatively, immediately postoperatively (except for ODI [9] and extension-flexion radiographs), and at 6, 12, and 24 months subsequently. Clinical evaluation consisted of ODI Version 2.0 [9], pain severity using 0- to 100-mm VAS pain scores for back (VASback) and leg (VASleg), blood loss, duration of surgery, length of hospitalization, and major or minor complications [4].

To determine the implant failure rate, two observers (PS, EH) screened all radiographs for implant failures in a blinded fashion with respect to the following parameters: implant failure as suggested by screw loosening, implant dislocation, or breakage of a screw, rod, or the titanium alloy cable of the spacer; and persisting motion in the dynamically stabilized segment (yes/no) in extension-flexion radiographs. The analysis of interobserver variability for these variables was performed using the interclass correlation coefficient, with all being greater than 0.89. A third independent orthopaedic surgeon (MP) adjudicated on conflicting findings. To detect potential predictive parameters for implant failure, we used averaged values from the two observers for the variables listed below, derived from plain and extension-flexion radiographs. These were compared between subgroups of patients with and without implant failure, employing a two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test for the first postoperative followup. Normality of the distribution was checked with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test before applying parametric testing. For the dynamically stabilized and superior adjacent segments, parameters were posterior and anterior disc height, lordotic angle, ROM, and implant translation in the neutral position of the dynamically stabilized segment (connected with sagittal kinking of the titanium alloy cable of the spacer). The comparison was then repeated within the SL and TO groups.

To detect differences in radiographic changes in the dynamically stabilized and superior adjacent segments between the SL and TO groups, we compared the parameters listed above using a two-way ANOVA for repeated measures with post hoc Bonferroni tests for all postoperative time points. Normality of the distribution was checked with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test before applying parametric testing. Analyses resulted in p values for the influence of treatment (ptreatment) (SL versus TO) regardless of the time course, for the changes over time (ptime) regardless of the intervention, and the combined influence of treatment over time (ptreatment × time). To determine whether clinical scores for patients with implant failure were inferior to those without, we compared these subgroups with respect to the ODI and VASback and VASleg for all patients and subsequently for the SL and TO groups. Comparison was performed using two-way ANOVA for repeated measures resulting in p values for the independent influences of implant failure (pIF) and time (ptime) and implant failure over time (pIF × time), with post hoc Bonferroni tests for 12- and 24-month followup (when implant failure was present). The influence of implant configuration on the parameters ODI and VASback and VASleg was examined by comparison of the SL and TO groups using a two-way ANOVA for repeated measures, resulting in p values for configuration (pconfig), time (ptime), and configuration over time (pconfig × time) with post hoc Bonferroni tests for each postoperative followup. Normality of the distribution was checked with Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests before applying parametric testing. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS® 17.0 statistics software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism® 5 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

In four of the 17 patients of the SL group and six of the 20 patients of the TO group, we observed implant failures, which were all related to breakage of the titanium alloy cable (Fig. 2), with one patient in each group at the 12-month followup and all others at the 24-month followup. The subgroup with implant failure in both groups presented larger direct postoperative implant translation (overall, p < 0.001; SL, p = 0.079; TO, p < 0.001). Furthermore, postoperative posterior disc height was greater for the subgroup of patients with implant failure within the SL group (Table 2). In patients with large implant translation, we unexpectedly observed this translation to be fixed in extension and flexion, regardless of the direction of translation (anterior versus posterior) (Fig. 3). Small implant translations resulted in physiologic motion behavior of the dynamically instrumented level in extension-flexion.

Fig. 2A–C.

(A) A TO implant is shown after removal from a patient requiring surgical revision because of a ruptured titanium alloy cable 26 months after implantation. (B) Lateral and (C) AP radiographs show a representative case of implant failure with breakage (*) and subsequent migration (#) of the cable.

Table 2.

Radiographic parameters at first followup

| Parameter | Without implant failure | With implant failure | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||

| Implant translation (mm) | 2.3 ± 0.33 | 4.6 ± 0.34 | < 0.001 |

| Posterior disc height (mm) | 6.7 ± 0.28 | 7.0 ± 0.67 | 0.698 |

| Anterior disc height (mm) | 10.3 ± 0.35 | 10.6 ± 0.94 | 0.687 |

| Lordotic angle (°) | 6.8 ± 0.83 | 6.5 ± 1.70 | 0.869 |

| ROM (°) | 6.1 ± 0.49 | 6.9 ± 0.74 | 0.383 |

| SL group | |||

| Implant translation (mm) | 2.4 ± 0.48 | 4.3 ± 0.83 | 0.079 |

| Posterior disc height (mm) | 6.8 ± 0.34 | 8.9 ± 0.55 | 0.009 |

| Anterior disc height (mm) | 10.1 ± 0.54 | 11.1 ± 1.23 | 0.391 |

| Lordotic angle (°) | 6.16 ± 1.20 | 3.6 ± 1.71 | 0.300 |

| ROM (°) | 5.8 ± 0.59 | 5.2 ± 0.82 | 0.625 |

| TO group | |||

| Implant translation (mm) | 2.2 ± 0.38 | 4.8 ± 0.23 | < 0.001 |

| Posterior disc height (mm) | 6.6 ± 0.53 | 5.7 ± 0.63 | 0.295 |

| Anterior disc height (mm) | 10.6 ± 0.32 | 10.3 ± 1.41 | 0.809 |

| Lordotic angle (°) | 7.8 ± 0.95 | 8.4 ± 2.37 | 0.794 |

| ROM (°) | 6.6 ± 0.87 | 8.0 ± 0.89 | 0.312 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD; all parameters were derived from immediate postoperative radiographs, except ROM (6-month followup); SL = single-level; TO = topping-off.

Fig. 3A–C.

Radiographs show representative kinking of the titanium alloy cable (*) in a patient from the TO group. (A) AP translation is visible in the lateral radiograph in neutral position. (B) Despite segmental motion under flexion stress, a lateral radiograph demonstrates an almost fixed retrolisthesis of the implant. (C) Similar retrolisthesis can be observed in a lateral radiograph under extension stress.

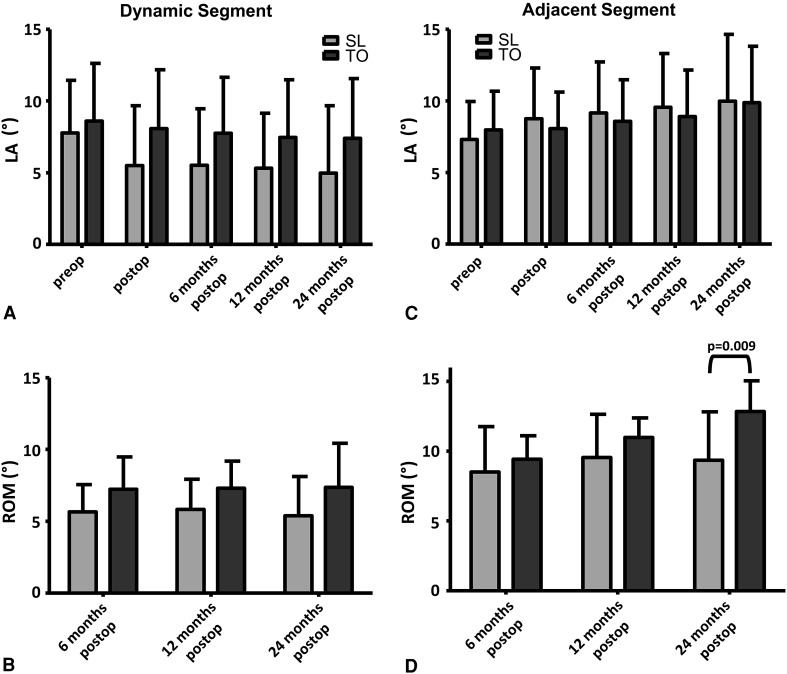

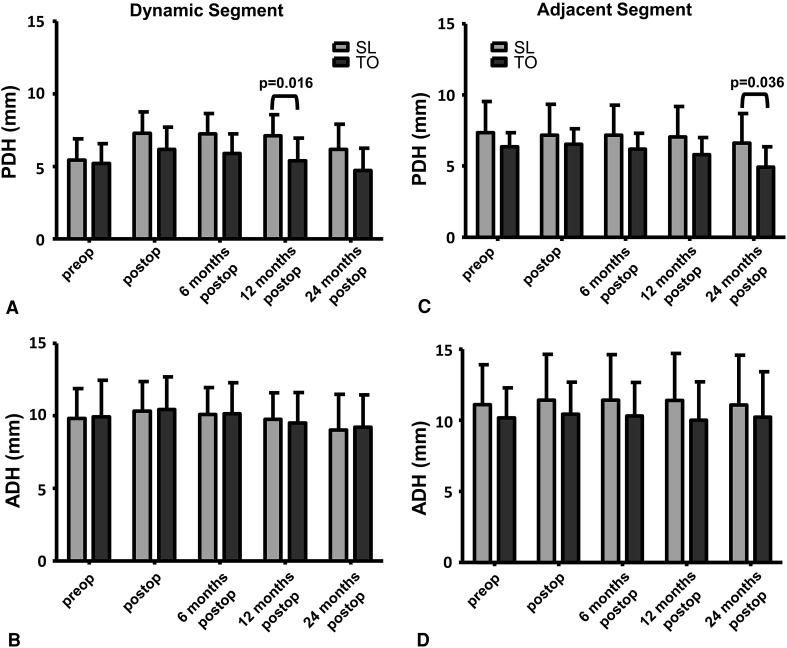

In the TO group relative to the SL group, ROM was greater in the dynamically stabilized (ptreatment = 0.033) and adjacent segment (ptreatment = 0.041) and increased more over time (ptreatment × time = 0.006) (Fig. 4); also, posterior disc height was smaller (ptreatment = 0.011) in the dynamically stabilized segment and decreased more over time (ptreatment × time = 0.002) (Fig. 5). The lordotic angle and ROM increased (ptime < 0.001) only in the adjacent segment (Fig. 4). We observed a decrease over time (each ptime < 0.001) in the posterior and anterior disc heights in the dynamically stabilized segment and in the posterior disc height in the adjacent segment (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4A–D.

Graphs compare the mean values of (A, C) lordotic angle (LA) and (B, D) ROM between the SL and TO groups in the (A, B) dynamically stabilized and (C, D) superior adjacent segments over time. ROM was greater in the dynamically stabilized (ptreatment = 0.033) and superior adjacent (ptreatment = 0.041) segments and increased more in the superior adjacent segment over time (ptreatment × time = 0.006) in the TO group than in the SL group. The lordotic angle and ROM were constant in the dynamically stabilized segment, while both parameters increased in the superior adjacent segment (each ptime < 0.001). Whisker = SD; preop = preoperative; postop = postoperative. Bracket indicates only significant factor in post hoc tests.

Fig. 5A–D.

Graphs compare the mean values of (A, C) posterior disc height (PDH) and (B, D) anterior disc height (ADH) for the (A, B) dynamically stabilized and (C, D) superior adjacent segments between the SL and TO groups over time. In the dynamically stabilized segment the posterior disc height was smaller (ptreatment = 0.011) and decreased more over time (ptreatment × time = 0.002) in the TO group than in the SL group. The posterior and anterior disc heights in the dynamically stabilized segment and the posterior disc height in the superior adjacent segment decreased (each ptime < 0.001) over time. Whisker = SD; preop = preoperative; postop = postoperative. Bracket indicates only significant factors in post hoc tests.

Implant failure was associated with inferior VASback (overall, pIF = 0.001; SL, pIF = 0.008; TO, pIF = 0.046) and ODI (SL, pIF = 0.017). ODI increased when implant failure was observed (overall, pIF × time = 0.013) (Table 3). Comparing to the SL configuration, the TO configuration was connected with inferior clinical scores (ODI pconfig = 0.002; VASback pconfig = 0.010; VASleg pconfig = 0.049; Fig. 6).

Table 3.

Scores for pain and function of patients with and without incidence of implant failure

| Time | Overall | SL goup | TO group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No implant failure | Implant failed | No implant failure | Implant failed | No implant failure | Implant failed | |

| ODI (%) | ||||||

| 12 months* | 35.4 ± 21.05 | 47.2 ± 11.62 | 24.7 ± 12.52 | 45.0 ± 11.14 | 46.1 ± 22.71 | 48.7 ± 12.75 |

| 24 months* | 35.3 ± 21.58 | 49.6 ± 22.13 | 22.7 ± 15.82 | 42.0 ± 15.58 | 47.9 ± 19.41 | 54.7 ± 25.66 |

| ptime | 0.624 | 0.407 | 0.274 | |||

| pIF | 0.078 | 0.017 | 0.633 | |||

| pIF × time | 0.581 | 0.867 | 0.539 | |||

| VASback (mm) | ||||||

| 12 months* | 41.3 ± 23.99† | 68.3 ± 16.17† | 29.9 ± 23.90 | 66.0 ± 18.99 | 52.6 ± 18.66 | 69.8 ± 15.73 |

| 24 months* | 39.3 ± 24.25† | 70.3 ± 18.71† | 27.9 ± 24.03‡ | 68.5 ± 21.11‡ | 50.6 ± 19.12 | 71.5 ± 18.93 |

| ptime | 0.992 | 0.945 | 0.930 | |||

| pIF | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.046 | |||

| pIF × time | 0.260 | 0.538 | 0.234 | |||

| VASleg (mm) | ||||||

| 12 months* | 33.2 ± 24.16 | 50.2 ± 27.39 | 23.1 ± 21.87 | 47.5 ± 30.96 | 43.2 ± 22.73 | 52.0 ± 27.67 |

| 24 months* | 35.3 ± 29.26 | 46.4 ± 28.37 | 29.6 ± 29.09 | 36.3 ± 21.88 | 40.9 ± 29.39 | 53.2 ± 32.00 |

| ptime | 0.822 | 0.612 | 0.920 | |||

| pIF | 0.136 | 0.284 | 0.391 | |||

| pIF × time | 0.447 | 0.071 | 0.767 | |||

* Values are presented as mean ± 1 SD; †significantly different in post hoc tests (p < 0.01); ‡significantly different in post hoc tests (p < 0.05); SL = single-level; TO = topping-off; ODI = Oswestry Disability Index; VASback = VAS score for back pain; VASleg = VAS score for leg pain; ptime, pIF, and pIF × time = p values for the independent influences of time, implant failure, and implant failure over time.

Fig. 6A–C.

Graphs compare the mean values for (A) ODI, (B) VASback, and (C) VASleg overall and in the SL and TO groups. The TO group was associated with inferior ODI and VAS pain scores (ODI pconfig = 0.002; VASback pconfig = 0.010; VASleg pconfig = 0.049). At each postoperative followup and within all three scores and both groups (SL and TO), parameters improved compared to the preoperative status (each ptime < 0.001). Whisker = SD; preop = preoperative; postop = postoperative. Bracket indicates only significant factors in post hoc tests.

Apart from implant failure, we observed no major complications and five minor complications (TO: three; SL: two) during the study period. The minor complications included a urinary tract infection treated by antibiotic therapy, an ileus resolved by laxative medication, and a transient sciatica with complete remission after local infiltration into the iliosacral joint in the TO group and a transient postoperative delirium that disappeared without any specific therapy within 2 days and a superficial hematoma with no need of intervention in the SL group. The implant failures led to reoperation in clinically symptomatic patients (SL: two of four; TO: two of six) who wanted the implant removed after the last followup.

Discussion

ASD remains one of the major problems after lumbar spinal fusion. Dynamic stabilization instead of fusion and its use adjacent to fusion are two approaches to potentially avoid ASD [20, 35, 54]. We prospectively analyzed the clinical and radiographic 2-year outcomes of the CD Horizon® Agile™ Spinal System, a new pedicle screw-based implant for dynamic stabilization in two construct configurations (SL and TO), which was recalled from the market shortly after its launch in 2007. The biomechanical reason for the high implant failure rate of this system remains unknown. We therefore determined (1) the complication rate for the SL and TO implant configurations and which postoperative radiographic parameters were linked to implant failure; (2) whether the changes in the radiographic parameters were different between the two configurations; and (3) whether implant failure or configuration was associated with inferior clinical scores.

We note limitations to our study. The first is the small number of patients: with cessation of the trial due to high failure rates, no further patients could be enrolled. Our study included the largest population investigated after insertion of this implant (40 patients; loss from followup 7% at 2 years). The only other study available [19] reported on 15 patients with an average followup of 19 months (range, 12–25 months). Second, a followup of 2 years is short for a new implant; however, our data document clinically relevant implant-associated complications, even after this short period. Third, the small number of patients does not allow for a rigorous multivariable analysis, including potentially confounding variables, and our data should be considered preliminary. However, the relatively high number of failures reduced the need for such an analysis. Fourth, no control group was planned in the original study; however, we contributed to a multicenter observational study with a fixed design. A control group possibly would have increased the level of evidence of the present study and would have enabled comparison to standard procedures such as decompression only or fusion. Therefore, only comparison to the literature is possible.

The implant failure rates observed for our SL (23.5%) and TO (30%) groups were higher than those reported in the retrospective study mentioned above [19] using the same implant. This study also showed improvement in mean ODI and VAS pain scores at followup times of 12 to 25 months (Table 4). That study included patients with younger age and a lower grade of DDD, requiring fewer destabilizing operative procedures, which is a possible reason for these diverging findings. In fact, the high failure rate of the Agile™ implant subsequently led to its recall. For other posterior dynamic stabilization systems, such as Dynesys® or Cosmic™, lower implant failure rates (0%–14%; Table 4) have also been reported [35, 37, 50, 53]. In these studies, implant failures exclusively consisted of screw loosening or breakage of screws or rods, whereas we observed failure only in the dynamic part of the implant. The best predictive parameter in both groups for the future failure of the Agile™ implant was postoperative implant translation. Surprisingly, the implant translation remained fixed in extension-flexion; to our knowledge, this has not been previously reported for any other posterior dynamic implant. The findings of two recent biomechanical studies [45, 47] suggest a system’s shear stiffness is the critical factor in achieving stabilization in the transverse plane. Additionally, shear stiffness depends more on the implant design than on the implant material itself [40, 45]. Obviously, the design of the Agile™ implant is not suitable to resist high translational forces. However, because resistance to rotational and translational forces is reduced in initially degenerated segments [10, 30, 41], stabilization in the transverse plane in particular is necessary. In the SL group, another predictive parameter for implant failure was a larger postoperative posterior disc height. Due to an increase in the load on the implant when distracting the segment posteriorly, shear forces also increase [39, 40]. This could explain the implant failure.

Table 4.

Literature review of clinical results, implant failure, and revision rates for single-level dynamic stabilization alone and adjacent to fusion (hybrid instrumentation)

| Study | Implant | Study design | Mean followup (months) | Number of patients | Indication | Improvement on 0- to 100-mm VAS for pain (mm) | ODI improvement (%) | Implant failure rate (%) | Overall surgical revision rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-level dynamic | |||||||||

| Grevitt et al. [13] (1995) | Graf ligaments | Prospective | 24 | 50 | DDD with LBP | 28 | |||

| Hadlow et al. [16] (1998) | Graf ligaments | Retrospective | 24 | 83 | LBP | 72 | |||

| Kanayama et al. [18] (2007) | Graf ligaments | Retrospective | Minimum 10 years | 43 | NP, stenosis, instability, scoliosis | Final VAS 13 back 9 leg |

7 | ||

| Saxler et al. [43] (2005) | Graf ligaments | Retrospective | 79 | 26 | NP or instability with/without stenosis | 46.7 | 23 | ||

| Stoll et al. [51] (2002) | Dynesys® | Prospective | 38 | 83 | Instability and stenosis or DDD or NP | 43 back 45 leg |

32.5 | 8.4 | 13.2 |

| Grob et al. [14] (2005) | Dynesys® | Retrospective | Up to 24 | 50 | DDD or stenosis with instability | 23 back 42 leg |

19 | ||

| Bothmann et al. [3] (2008) | Dynesys® | Prospective | 16 | 33 | DDD or stenosis or instability, spondylolisthesis | 33 back 40 leg |

22.5† | 30† | |

| Putzier et al. [36] (2004) | Dynesys® | Retrospective | 33 | 70 | NP and initial DDD | 60 | 57 | 0 | 0 |

| Facet joint arthrosis and initial DDD | 60 | 50 | 4.5 | ||||||

| Spondylolisthesis and initial DDD | 15 | 10 | 30.8 | ||||||

| Putzier et al. [37] (2005) | Dynesys® | Prospective | 34 | 35 | NP and initial DDD | 59 | 58 | 0 | 0 |

| Bordes-Monmeneu et al. [2] (2005) | Dynesys® | Retrospective | 14–24 | 94 | NP, DDD, stenosis | 35.4 | 4 | ||

| Schaeren et al. [44] (2008) | Dynesys® | Prospective | 52 | 19 | Spondylolisthesis with stenosis | 55 | 16 | 16 | |

| Schnake et al. [48] (2006) | Dynesys® | Prospective | 24 | 25 | Spondylolisthesis with stenosis | 57 | 17 | ||

| Plev and Sutcliffe [34] (2005) | Dynesys® | Retrospective | 12 | 79 | LBP | 44.9 | 12.7 | ||

| Delamarter et al. [7] (2006) | Dynesys® | Prospective | 24 | 84 | Spondylolisthesis with/without stenosis | 31 back 67 leg |

25.2 | 0 | 4 |

| Maleci et al. [25] (2011) | Cosmic™ | Retrospective | 24 | 139 | DDD with/without spondylolisthesis and stenosis | 48 | 26.4 | 8.6 | 7.9 |

| Stoffel et al. [50] (2010) | Cosmic™ | Prospective | 15 | 100 | Instability and/or stenosis | 44 | 30 | 2 | 22 |

| Hybrid | |||||||||

| Maserati et al. [26] (2010) | Dynesys® topping off | Retrospective | 8 | 22 | Initial DDD | 35 | 12 | ||

| Putzier et al. [35] (2010) | Dynesys® Transition | Prospective | 76 | 22 | Initial DDD | 40 | 37 | 41 | |

| Kaner et al. [19] (2009) | Agile™ topping off* | Retrospective | 19 | 15 | DDD | 59 | 57.6 | 6.7 | 6.7 |

| Current study | |||||||||

| Single-level dynamic | Agile™ | Prospective | 24 | 17 | NP with DDD, stenosis | 26 back 42 leg |

24 | 23.6 | 0 |

| Hybrid | Agile™ topping off | Prospective | 24 | 20 | Initial DDD | 19 back 20 leg |

14 | 30 | 0 |

* The study contained one patient with single-level use of the Agile™ implant; †implant failure rate and surgical revision rate were calculated from 40 patients since the study also reported bi- or trilevel surgery outcomes; DDD = degenerative disc disease; LBP = low back pain; NP = nucleus prolapse (including recurrent nucleus prolapse).

We found the ROM of the dynamically stabilized segment and its superior adjacent segment was higher, reflecting a higher load on these segments when using the implant as an adjunct to rigid instrumentation (TO). This is consistent with the findings of one biomechanical investigation of such posterior hybrid instrumentation [52]. The increase in load apparently led to a further increase in ROM in the adjacent segment over time. Together with a progressive loss of the adjacent segment’s posterior disc height, this can be interpreted as progression of ASD in the uninstrumented level [8, 23, 24]. Such ASD superior to the dynamic construct was also reported for other implants [35, 50]. The higher ROM in the dynamically stabilized segment within the TO group is possibly related to the slightly higher implant failure rate in this group. Because of the insufficiency of the dynamic implant in compensating for shear forces and because of the increased disc load due to the posterior shift of the center of rotation, as described for most posterior dynamic devices [39, 40], progression of DDD of the dynamically stabilized segment was observed in both groups. This is reflected by the decrease of anterior and posterior disc heights over time.

Unsurprisingly, implant failure was associated with worse clinical results, as represented by VASback and ODI in both groups. Investigations into the association between implant failure and clinical scores are rare. The mean improvement in the clinical scores of the SL group (ODI, 24 %; VASback, 26 mm; VASleg, 42 mm) ranked at a level comparable or inferior to that in other studies where single-level dynamic stabilization was performed with similar inclusion criteria (Table 4), but clinical evaluation with respect to implant failure was not performed in these patients. In a recent study, implant failure of another hybrid construct (Dynesys® Transition) did not lead to inferior clinical results [35]. Within that study, occurrence of implant failure was late and only at the fusion level, whereas vertebrae were bridged already in most patients, which may be the reason for the low rate of clinical symptoms. In our study, the ODI and VAS pain scores of the TO group were inferior to those reported by Putzier et al. [35], but the indications and type of implant failure were different. Regarding VAS pain scores and ODI, the results reported by Maserati et al. [26] for the Dynesys®-to-Optima™ hybrid system were similar to those of our TO group (Table 4). However, the clinical improvement for patients with TO reached only about 15% (ODI), 19 mm (VASback), and 20 mm (VASleg) at last followup.

In conclusion, the hitherto underrepresented issue of compensation for shear forces that lead to translation should be addressed in future implant designs. Beyond this, translational stability testing should be included as standard for the evaluation of any spinal implant, but especially for posterior dynamic stabilization devices, before their clinical application. Additionally, future posterior dynamic implants must provide sufficient stabilization in neutral position to be successful. Usage of posterior dynamic stabilization as an adjunct to fusion results in higher implant failure rates due to increased compensatory loads on the implant. Because using posterior hybrid instrumentation also failed to prevent ASD, further investigation of the mechanism of load transfer is needed before clinical application of posterior dynamic devices.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cameron J. Wilson for proofreading and language checking of the article. Authors Eike Hoff and Patrick Strube have contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or any member of his/her immediate family, has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Bono CM, Kadaba M, Vaccaro AR. Posterior pedicle fixation-based dynamic stabilization devices for the treatment of degenerative diseases of the lumbar spine. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22:376–383. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31817c6489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bordes-Monmeneu M, Bordes-Garcia V, Rodrigo-Baeza F, Saez D. [System of dynamic neutralization in the lumbar spine: experience on 94 cases] [in Spanish] Neurocirugia [Asturias, Spain] 2005;16:499–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bothmann M, Kast E, Boldt GJ, Oberle J. Dynesys fixation for lumbar spine degeneration. Neurosurg Rev. 2008;31:189–196. doi: 10.1007/s10143-007-0101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho KJ, Suk SI, Park SR, Kim JH, Kim SS, Choi WK, Lee KY, Lee SR. Complications in posterior fusion and instrumentation for degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:2232–2237. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31814b2d3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou WY, Hsu CJ, Chang WN, Wong CY. Adjacent segment degeneration after lumbar spinal posterolateral fusion with instrumentation in elderly patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:39–43. doi: 10.1007/s004020100314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chow DH, Luk KD, Evans JH, Leong JC. Effects of short anterior lumbar interbody fusion on biomechanics of neighboring unfused segments. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:549–555. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199603010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delamarter RB, Maxwell J, Davis R, Sherman J, Welch W. Nonfusion application of the Dynesys system in the lumbar spine: early results from the IDE Multicenter Trial. Spine J. 2006;6(suppl):77S. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.06.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupuis PR, Yong-Hing K, Cassidy JD, Kirkaldy-Willis WH. Radiologic diagnosis of degenerative lumbar spinal instability. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1985;10:262–276. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198504000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairbank TC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2940–2952. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujiwara A, Tamai K, Yamato M, An HS, Yoshida H, Saotome K, Kurihashi A. The relationship between facet joint osteoarthritis and disc degeneration of the lumbar spine: an MRI study. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:396–401. doi: 10.1007/s005860050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerbershagen HU, Lindena G, Korb J, Kramer S. [Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic pain] [in German] Schmerz (Berlin, Germany) 2002;16:271–284. doi: 10.1007/s00482-002-0164-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghiselli G, Wang JC, Bhatia NN, Hsu WK, Dawson EG. Adjacent segment degeneration in the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1497–1503. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grevitt MP, Gardner AD, Spilsbury J, Shackleford IM, Baskerville R, Pursell LM, Hassaan A, Mulholland RC. The Graf stabilisation system: early results in 50 patients. Eur Spine J. 1995;4:169–175. doi: 10.1007/BF00298241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grob D, Benini A, Junge A, Mannion AF. Clinical experience with the Dynesys semirigid fixation system for the lumbar spine: surgical and patient-oriented outcome in 50 cases after an average of 2 years. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:324–331. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000152584.46266.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ha KY, Schendel MJ, Lewis JL, Ogilvie JW. Effect of immobilization and configuration on lumbar adjacent-segment biomechanics. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:99–105. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199304000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadlow SV, Fagan AB, Hillier TM, Fraser RD. The Graf ligamentoplasty procedure: comparison with posterolateral fusion in the management of low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:1172–1179. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199805150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hambly MF, Wiltse LL, Raghavan N, Schneiderman G, Koenig C. The transition zone above a lumbosacral fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:1785–1792. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199808150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanayama M, Hashimoto T, Shigenobu K, Togawa D, Oha F. A minimum 10-year follow-up of posterior dynamic stabilization using Graf artificial ligament. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1992–1996. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318133faae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaner T, Sasani M, Oktenoglu T, Cosar M, Ozer AF. Utilizing dynamic rods with dynamic screws in the surgical treatment of chronic instability: a prospective clinical study. Turk Neurosurg. 2009;19:319–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaner T, Sasani M, Oktenoglu T, Ozer AF. Dynamic stabilization of the spine: a new classification system. Turk Neurosurg. 2010;20:205–215. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.2358-09.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar MN, Baklanov A, Chopin D. Correlation between sagittal plane changes and adjacent segment degeneration following lumbar spine fusion. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:314–319. doi: 10.1007/s005860000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar MN, Jacquot F, Hall H. Long-term follow-up of functional outcomes and radiographic changes at adjacent levels following lumbar spine fusion for degenerative disc disease. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:309–313. doi: 10.1007/s005860000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leone A, Cassar-Pullicino VN, Guglielmi G, Bonomo L. Degenerative lumbar intervertebral instability: what is it and how does imaging contribute? Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:529–533. doi: 10.1007/s00256-009-0646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leone A, Guglielmi G, Cassar-Pullicino VN, Bonomo L. Lumbar intervertebral instability: a review. Radiology. 2007;245:62–77. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2451051359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maleci A, Sambale RD, Schiavone M, Lamp F, Ozer F, Strempel A. Nonfusion stabilization of the degenerative lumbar spine. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;15:151–158. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.SPINE0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maserati MB, Tormenti MJ, Panczykowski DM, Bonfield CM, Gerszten PC. The use of a hybrid dynamic stabilization and fusion system in the lumbar spine: preliminary experience. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E2. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.FOCUS1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyerding HW. Spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1931;13:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyakoshi N, Abe E, Shimada Y, Okuyama K, Suzuki T, Sato K. Outcome of one-level posterior lumbar interbody fusion for spondylolisthesis and postoperative intervertebral disc degeneration adjacent to the fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:1837–1842. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modic MT, Steinberg PM, Ross JS, Masaryk TJ, Carter JR. Degenerative disk disease: assessment of changes in vertebral body marrow with MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;166:193–199. doi: 10.1148/radiology.166.1.3336678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niosi CA, Zhu QA, Wilson DC, Keynan O, Wilson DR, Oxland TR. Biomechanical characterization of the three-dimensional kinematic behaviour of the Dynesys dynamic stabilization system: an in vitro study. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:913–922. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0948-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park P, Garton HJ, Gala VC, Hoff JT, McGillicuddy JE. Adjacent segment disease after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:1938–1944. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000137069.88904.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penta M, Sandhu A, Fraser RD. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of disc degeneration 10 years after anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:743–747. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199503150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pihlajamaki H, Bostman O, Ruuskanen M, Myllynen P, Kinnunen J, Karaharju E. Posterolateral lumbosacral fusion with transpedicular fixation: 63 consecutive cases followed for 4 (2–6) years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:63–68. doi: 10.3109/17453679608995612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plev D, Sutcliffe JC. Outcome and complications using a dynamic neutralization and stabilization pedicle screw system (DYNESYS): is this a “soft fusion”? Spine J. 2005;5:S141–S142. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.05.282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Putzier M, Hoff E, Tohtz S, Gross C, Perka C, Strube P. Dynamic stabilization adjacent to single-level fusion. Part II. No clinical benefit for asymptomatic, initially degenerated adjacent segments after 6 years follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:2181–2189. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1517-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Putzier M, Schneider SV, Funk J, Perka C. [Application of a dynamic pedicle screw system (DYNESYS) for lumbar segmental degenerations—comparison of clinical and radiological results for different indications] [in German] Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2004;142:166–173. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-818781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Putzier M, Schneider SV, Funk JF, Tohtz SW, Perka C. The surgical treatment of the lumbar disc prolapse: nucleotomy with additional transpedicular dynamic stabilization versus nucleotomy alone. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:E109–E114. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000154630.79887.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahm MD, Hall BB. Adjacent-segment degeneration after lumbar fusion with instrumentation: a retrospective study. J Spinal Disord. 1996;9:392–400. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199610000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rohlmann A, Burra NK, Zander T, Bergmann G. Comparison of the effects of bilateral posterior dynamic and rigid fixation devices on the loads in the lumbar spine: a finite element analysis. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1223–1231. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0292-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohlmann A, Nabil Boustani H, Bergmann G, Zander T. Effect of a pedicle-screw-based motion preservation system on lumbar spine biomechanics: a probabilistic finite element study with subsequent sensitivity analysis. J Biomech. 2010;43:2963–2969. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rohlmann A, Zander T, Schmidt H, Wilke HJ, Bergmann G. Analysis of the influence of disc degeneration on the mechanical behaviour of a lumbar motion segment using the finite element method. J Biomech. 2006;39:2484–2490. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruberte LM, Natarajan RN, Andersson GB. Influence of single-level lumbar degenerative disc disease on the behavior of the adjacent segments—a finite element model study. J Biomech. 2009;42:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saxler G, Wedemeyer C, Knoch M, Render UM, Quint U. Follow-up study after dynamic and static stabilisation of the lumbar spine] [in German. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2005;143:92–99. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-836250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaeren S, Broger I, Jeanneret B. Minimum four-year follow-up of spinal stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis treated with decompression and dynamic stabilization. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:E636–E642. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817d2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schilling C, Kruger S, Grupp TM, Duda GN, Blomer W, Rohlmann A. The effect of design parameters of dynamic pedicle screw systems on kinematics and load bearing: an in vitro study. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:297–307. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1620-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlegel JD, Smith JA, Schleusener RL. Lumbar motion segment pathology adjacent to thoracolumbar, lumbar, and lumbosacral fusions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:970–981. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199604150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt H, Heuer F, Wilke HJ. Which axial and bending stiffnesses of posterior implants are required to design a flexible lumbar stabilization system? J Biomech. 2009;42:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schnake KJ, Schaeren S, Jeanneret B. Dynamic stabilization in addition to decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:442–449. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000200092.49001.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sengupta DK. Dynamic stabilization devices in the treatment of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004;35:43–56. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(03)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stoffel M, Behr M, Reinke A, Stuer C, Ringel F, Meyer B. Pedicle screw-based dynamic stabilization of the thoracolumbar spine with the Cosmic-system: a prospective observation. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010;152:835–843. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0583-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoll TM, Dubois G, Schwarzenbach O. The dynamic neutralization system for the spine: a multi-center study of a novel non-fusion system. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(suppl 2):S170–S178. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0438-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strube P, Tohtz S, Hoff E, Gross C, Perka C, Putzier M. Dynamic stabilization adjacent to single-level fusion. Part I. Biomechanical effects on lumbar spinal motion. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:2171–2180. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1549-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wurgler-Hauri CC, Kalbarczyk A, Wiesli M, Landolt H, Fandino J. Dynamic neutralization of the lumbar spine after microsurgical decompression in acquired lumbar spinal stenosis and segmental instability. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:E66–E72. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816245c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zander T, Rohlmann A, Burra NK, Bergmann G. Effect of a posterior dynamic implant adjacent to a rigid spinal fixator. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2006;21:767–774. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]