Abstract

Background

A novel calcium sulfate–calcium phosphate composite injectable bone graft substitute has been approved by the FDA for filling bone defects in a nonweightbearing application based on preclinical studies. Its utility has not been documented in the literature.

Questions/purposes

We therefore determined postoperative function and complications in patients with benign bone lesions treated with this bioceramic.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed all 56 patients with benign bone lesions treated with the bioceramic from 2006 to 2008. There were 29 male and 27 female patients with an average age of 17.6 years (range, 4–63 years). They were treated for the following diagnoses: unicameral bone cyst (13), aneurysmal bone cyst (10), nonossifying fibroma (eight), fibrous dysplasia (five), enchondroma (four), chondroblastoma (four), and other (12). We obtained a Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) functional evaluation on all patients. The minimum followup was 26 months (average, 42 months; range, 26–57 months).

Results

The average MSTS score was 29 (range, 20–30). Most patients returned to normal function. There were three local recurrences, all of which were treated with repeat injection or curettage. Two patients had postoperative fractures treated in a closed manner. Two patients had wound complications, neither of which required removal of the graft material.

Conclusion

Patients treated with this material reported high MSTS functional scores more than 24 months after operative intervention and experienced low complication rates. We believe the novel bioceramic to be a reasonable treatment option for benign bone lesions.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Benign bone tumors and cysts are relatively common entities encountered in a general orthopaedic and orthopaedic oncology practice. This broad category encompasses lesions with widely varying clinical behaviors and natural histories. Treatment, therefore, must be individualized based on factors such as the specific tissue diagnosis, the size of the lesion, location of the lesion, associated symptoms, risk of pathologic fracture, and individual patient characteristics.

Traditionally, the autogenous bone graft has been the gold standard for all grafting procedures [16, 32]. Limited supply and substantial donor site morbidity, however, make this option less desirable [2, 3, 8, 10, 12, 13, 23, 26, 28]. Bone graft substitutes composed of calcium sulfate (CaSO4) or calcium phosphate (CaPO4) are reasonable alternatives because they are biodegradable [16, 21, 32] and osteoconductive [16, 21, 32]. Furthermore, they do not contain potent cytokines [16, 21, 32], which may be contraindicated in the presence of tumors. In a selective review, Rougraff documented the limited published data on the use of bone graft substitutes in orthopaedic oncology [24]. Most reported series using surgical-grade CaSO4 [16, 17, 20, 22] or CaPO4 [21] graft materials to treat patients with benign bone tumors are relatively small with short followup. While various bone graft substitutes may be used to treat bone lesions, common complications still exist [16, 17, 20, 21, 24]. One of the major factors in determining the quality of bone graft substitutes is the rate of graft incorporation into the host bone. Histologic assessment offers effective evaluation of the rate of graft incorporation but is considered impractical given the requirement of the patient to undergo an additional procedure for a bone biopsy [27]. The alternative to histologic analysis is radiographic assessment; however, the literature lacks defined standardized assessment guidelines for radiographic investigation of bone graft incorporation [27].

Recently, an injectable CaSO4-CaPO4 composite graft material with high compressive strength but an intermediate degradation profile has become available [32]. A preclinical canine study showed this material to be superior to CaSO4 regarding the quantity and quality of bone formed in a contained humeral defect [30–32]. This material incorporates a matrix of CaSO4 and dicalcium phosphate dihydrate (DCPD) into which β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) granules are distributed [32]. The resorption profile is triphasic. The CaSO4 resorbs first through simple dissolution, leaving behind an open-pore structure that allows for vascular infiltration and new bone deposition on the remaining CaPO4 scaffold. DCPD has an intermediate profile [32], resorbing by osteoclastic resorption and simple dissolution. Finally, β-TCP only undergoes osteoclastic resorption and thus is retained longest.

We present the first clinical report of the novel injectable CaSO4-CaPO4 composite graft material and specifically determined (1) the MSTS functional scores and the rates of (2) complications and (3) recurrences.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed all 56 patients with benign bone tumors and cysts who underwent open curettage and débridement and filling with an injectable bone graft substitute, PRO-DENSE® (Wright Medical Technology, Arlington, TN, USA) from 2006 to 2008. The indications for surgery in this study are benign bone tumors that are thought to need surgery because of their potential biology or risk of bone fracture thus leading to a contained osseous defect in a nonweightbearing clinical application. Latent stage 1 benign bone tumors were not treated and instead observed, but active (stage 2) and aggressive stage 3 benign bone tumors were routinely treated. The contraindications were: severe vascular or neurologic disease, uncontrolled diabetes, severe degenerative bone disease, closed bone void/gap filler, pregnancy, uncooperative patients who will not or cannot follow postoperative instructions including individuals who abuse drugs and/or alcohol, patients with hypercalcemia, patients with renal compromise, patients with a history of or active Pott’s disease, and patients with malignant tumors, segmental defects in long bone, and defects that require immediate postoperative weightbearing. This material was used in a consecutive series of patients who met the inclusion criteria. There were 29 male patients and 27 female patients. Their average age was 17.6 years (range, 4–63 years). Diagnoses included unicameral bone cyst (13), aneurysmal bone cyst (10), nonossifying fibroma (eight), fibrous dysplasia (five), enchondroma (four), chondroblastoma (four), and other (12), with 24 of the lesions located in the upper extremity and 32 located in the lower extremity (Table 1). The most common tumor or cyst locations were the humerus (15), femur (10), tibia (10), fibula (four), and other (17) (Table 2). Of the 56 patients, 10 were lost to followup and were unable to be contacted, leaving 46 patients. The minimum followup was 26 months (average, 42 months; range, 26–57 months). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Patient diagnoses

| Diagnoses | Number upper limb | Number lower limb | Total number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unicameral bone cyst | 9 | 4 | 13 |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Nonossifying fibroma | 0 | 8 | 8 |

| Fibrous dysplasia | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Enchondroma | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Chondroblastoma | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Other | 5 | 7 | 12 |

| Total | 24 | 32 | 56 |

Table 2.

Bone lesion location

| Location | Number |

|---|---|

| Humerus | 15 |

| Femur | 10 |

| Tibia | 10 |

| Fibula | 4 |

| Other | 17 |

| Total | 56 |

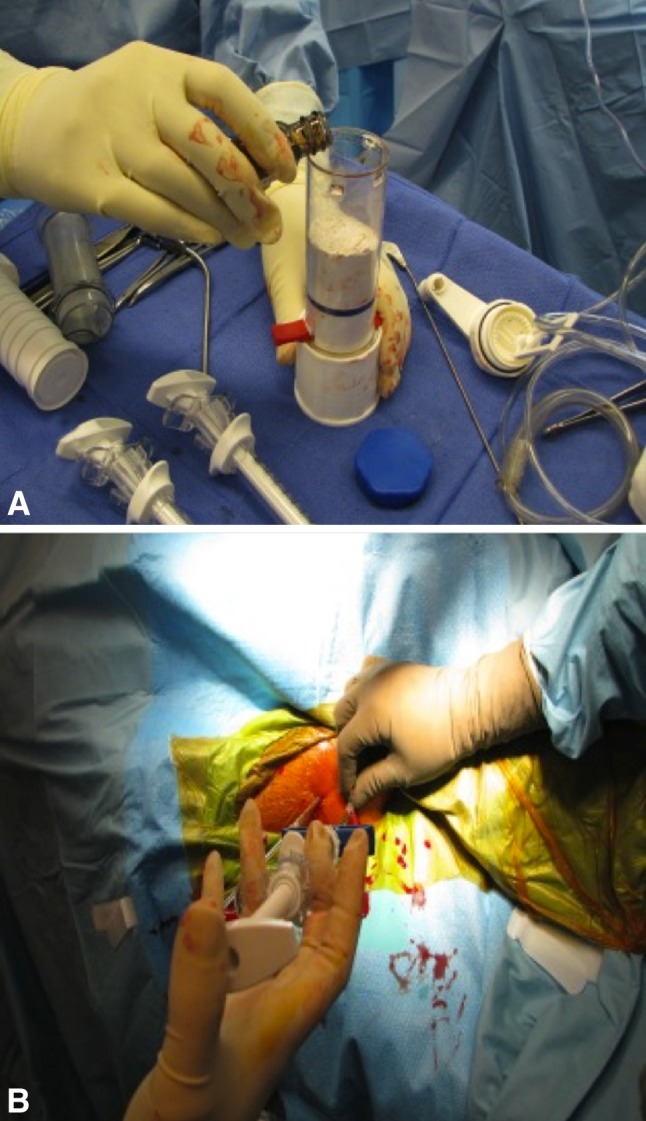

All patients were treated by one surgeon (SG). Thirteen lesions were treated with a percutaneous technique and 43 with open curettage. A percutaneous two-needle technique was used for diagnosis and treatment of unicameral bone cysts (Fig. 1); all other lesions were treated by an open approach. The lesion underwent biopsy and diagnosis was made by frozen section. The unicameral bone cysts were débrided through two 4-mm cannulas and then copiously lavaged after which PRO-DENSE® was injected through one cannula while using the other as a vent. The graft was prepared intraoperatively by mixing the powdered graft materials with aqueous diluents (Fig. 2A). The resulting composite is injectable for approximately 5 minutes and sets up in 20 to 30 minutes (Fig. 2B). Fluoroscopy was used to confirm that the entire cavity was filled. For open curettage, a longitudinal incision was made and a power burr used to create a cortical window. A biopsy specimen was taken and frozen section was performed. Curettes and elevators were used to remove lesional tissue. A power burr also was used to enlarge the tumor cavity. The tumor cavity then was irrigated with saline, dried, and filled with PRO-DENSE® (Fig. 3A). Postoperatively patients with lower extremity lesions were instructed to have protected weightbearing with the use of crutches for 8 weeks and patients with upper extremity lesions were instructed to avoid lifting objects for 8 weeks.

Fig. 1A−C.

(A) A preoperative radiograph shows a unicameral bone cyst in a 12-year-old boy. (B) A 1-month postoperative radiograph after percutaneous injection of PRO-DENSE® graft material is shown. (C) The 2-month postoperative radiograph shows ceramic degradation and bone formation.

Fig. 2A–B.

(A) The graft is prepared intraoperatively on the back table by mixing the powdered graft materials with an aqueous diluent. (B) The resulting composite then is injected into the lesion through a cannula with a separate cannula used as a vent. The graft is injectable for approximately 5 minutes and sets up in 20 to 30 minutes.

Fig. 3A–B.

(A) A postoperative radiograph is shown after open curettage and grafting of a distal tibial aneurysmal bone cyst in a 13-year-old girl. (B) A radiograph obtained 1 year after surgery shows degradation of the ceramic and bony remodeling.

After discharge from the hospital, usually on an outpatient basis, the patients were followed in the clinic at intervals of 1 week and 1, 6, 12, and 18 months. The intervals were altered at the surgeon’s discretion owing to variable healing rates and encountered complications. Each routine followup in the clinic included assessment of strength, ROM, functional status, and radiographic investigation to evaluate for potential fracture and presence of bone graft substitute (Figs. 1B–C, 3B).

We used the MSTS functional evaluation system to assess function [9]; the information required was obtained from patients through a survey during the period between January and May 2011. We obtained a completed MSTS functional evaluation from all patients who were not lost to followup. This survey consists of a list of qualitative responses for multiple categories associated with a graded, numerical score for the upper and lower limbs. In the lower limb, the survey evaluates emotional acceptance; supports including brace, prosthesis, cane, or crutches; walking ability; and gait. In the upper limb, the survey evaluates function, emotional acceptance, hand positioning, dexterity, and lifting ability. Each category is rated from zero to five with a maximum total score of 30.

Results

The average MSTS functional evaluation score was 29 (range, 20–30). The average score for patients with lower limb lesions was 29. The average for patients with upper limb lesions was slightly less at 28. The lowest score was 20 in a 32-year-old man with fibrous dysplasia of the humerus at 31 months followup. Twenty-three patients reported a perfect score of 30, eight of whom had upper limb lesions and 15 who had lower limb lesions.

Two patients (4%) had postoperative fractures. A 15-year-old boy with a nonossifying fibroma of the humerus sustained a fracture through his lesion 2 months postoperatively while playing soccer. This was treated with closed reduction and casting. He returned to full activity and went on to play two sports in college. The second fracture occurred in a 22-year-old woman with an enchondroma of the proximal phalanx of the fifth toe. All fractures healed with nonoperative treatment. Two patients (4%) had postoperative wound complications. The first was a 17-year-old boy who underwent curettage of a distal femur osteoid osteoma. He later had a superficial wound infection develop that was treated successfully with a 1-week course of oral antibiotics. Resolution was seen 1 month postoperatively. The other complication was in a 32-year-old man with fibrous dysplasia of the proximal humerus. He had a wound infection develop 1 month postoperatively requiring incision and drainage. He also was treated with a 7.5-week course of intravenous and oral antibiotics. He achieved full recovery without complications.

Three patients (7%) had local recurrences. A 14-year-old boy with a chondroblastoma of the proximal femur had a local recurrence 1 year postoperatively. He was treated with repeat curettage and grafting and was doing well at his most recent postoperative visit. A 43-year-old woman with a giant cell tumor of the proximal humerus had a local recurrence of tumor 6 months after the initial procedure. She later underwent repeat open curettage with bone autograft. The patient also was doing well at her last postoperative visit. The last recurrence was in a 9-year-old boy with a proximal humerus unicameral bone cyst who had a recurrence 1.5 years after his initial procedure. He later underwent repeat percutaneous treatment. He returned to full activity and now participates in hockey. One of the 13 patients with a unicameral bone cyst treated percutaneously underwent a second injection of PRO-DENSE® because of a local recurrence.

Discussion

PRO-DENSE® is a FDA-approved composite bioceramic for use in a contained osseous defect in a nonweightbearing application. Although a preclinical study [32] was promising, the literature contains no clinical report of this novel biomaterial. We therefore performed a retrospective case series of 56 patients treated with PRO-DENSE® for benign bone lesions to determine (1) the MSTS functional scores and the rates of (2) complications and (3) recurrences.

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. First, this is a relatively small study with short-term followup at an average of 3.5 years. Long-term followup is required to more adequately evaluate graft incorporation and bone remodeling. Second, this patient population is heterogeneous, including patients with multiple diagnoses of benign tumors and treated with percutaneous and open techniques. Owing to the small number of subjects in the study, comparison via surgical technique or diagnosis was deemed unreliable. Third, we did not assess radiographic incorporation of graft substitute owing to the lack of defined standardized assessment guidelines for radiographic investigation of bone graft incorporation.

The patients in our study achieved an average of 97% of that expected for normal function based on the observed average MSTS functional evaluation score of 29. Unfortunately only a limited number of studies could be identified in the literature that investigated the MSTS functional evaluation of bone graft and bone graft substitutes in the treatment of benign bone lesions (Table 3) [1, 11, 14, 16, 27]. Aho et al. [1] presented a study of 24 patients with benign bone lesions treated with an allograft who had an average MSTS functional evaluation of 83% with an average followup of 6 years. Gitelis et al. [11] reported on 23 patients with an average followup of 21 months who were treated with calcium sulfate for benign bone lesions and had an average MSTS functional evaluation of 98%. Hirata et al. [14] reported observations on 53 patients treated with β-TCP for benign bone lesions who had an average MSTS functional evaluation of 100%. Kelly and Wilkins [16] presented a study of 15 patients with benign bone lesions treated with calcium sulfate who had an average MSTS functional evaluation of 83% with an average followup of 6 months. Schindler et al. [27] reported findings for 13 patients treated with a composite ceramic bone graft substitute containing calcium sulfate and hydroxyapatite for benign bone tumors who had an average MSTS functional evaluation of 96% with an average followup of 41 months.

Table 3.

Literature comparison of functional outcomes in bone graft studies

| Study | Type of bone graft | Number of patients | Duration of followup | MSTS functional evaluation score* | Infection | Postoperative fracture | Local recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aho et al. [1] | Allograft | 24 | 72 months | 83% | 4% | 29% | 0% |

| Gitelis et al. [11] | Calcium sulfate | 23 | 21 months | 98% | 0% | 4% | 0% |

| Hirata et al. [14] | Tricalcium phosphate | 53 | NR | 100% | 0% | 0% | 4% |

| Kelly & Wilkins [16] | Calcium sulfate | 15 | 6 months | 83% | 7% | 7% | NR |

| Schindler et al. [27] | Calcium sulfate and hydroxyapatite | 13 | 41 months | 96% | NR | 8% | 15% |

| Current study | PRO-DENSE® | 46 | 42 months | 97% | 4% | 4% | 7% |

NR = not reported; *MSTS functional evaluation scores reported as a percentage of the perfect score of 30 points.

Complications in our patients were infrequent and in most cases likely were not attributable to the graft material. Two patients sustained postoperative fractures that healed with nonoperative treatment, and two experienced wound complications that did not require removal of the graft material. There were no other complications. This is comparable to other reported series of CaSO4 and CaPO4 bone graft substitutes [11, 16, 17, 20–22, 24, 32]. Complications, specifically tissue reaction and chronic wound drainage, appear to be decreased in our series compared with other series of patients treated with CaSO4 [16, 17, 20]. We hypothesized that the rapid dissolution profile of pure CaSO4 contributes to this complication. Thus, as expected, a composite graft with an intermediate profile appears to lessen the severity of the tissue reaction and wound problems. Furthermore, although not specifically quantified in this study, the composite graft material appears to exhibit the expected intermediate resorption profile and is gradually replaced by host bone (Fig. 4). This is in contrast to patients treated with pure CaPO4 bone graft substitutes in whom residual graft material can be seen for years postoperatively and possibly permanently [21, 24].

Fig. 4.

A CT scan obtained 19 months after percutaneous injection of PRO-DENSE® graft material in the proximal humerus unicameral bone cyst of a 12-year-old boy (patient in figures 1A–C) shows full degradation of the ceramic material with complete bone repair.

In the current series, three patients (7%) experienced local recurrence. Although the study was not intended to investigate the rate of recurrence of unicameral bone cysts as compared with alternative modes of treatment, a lower recurrence rate after percutaneous treatment with PRO-DENSE® was observed compared with rates reported in the literature [4–7, 15, 18, 25, 29, 33]. One of the 13 patients (8%) with a unicameral bone cyst experienced a recurrence. Authors have reported multiple percutaneous methods of treating unicameral bone cysts, the most common of which include injections with steroids [4–6, 29, 33], autogenous bone marrow aspirates [5, 6, 19, 33], demineralized bone matrix [18], and combinations of these [7, 15, 25, 29]. Although most patients can be treated by percutaneous methods, recurrence rates after the initial injections in these series range from 11% to 77%. In the current series, however, only one of the 13 (8%) unicameral bone cysts treated percutaneously has required a second injection. The remainder appeared to have healed with one injection. Although it was not an intended outcome, PRO-DENSE® appears to result in a lower recurrence rate after percutaneous treatment as compared with alternative treatment modalities.

With this new material we found high functional scores and infrequent complications compared with the literature. Based on these observations we believe it is a reasonable alternative to autogenous bone graft. Further study is needed to quantify the amount and rate of bone formation and the rate of graft dissolution for this material and other comparable materials over longer clinical periods. In addition, further investigation is required into the lower recurrence rate of unicameral bone cysts treated percutaneously with PRO-DENSE®.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pat Gargano for administrative assistance.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he (SG), or a member of their immediate family, has or may receive payments or benefits, in any one year, an amount in excess of $10,000, from a commercial entity (Wright Medical Technology, Arlington, TN, USA) related to this work.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Aho AJ, Ekfors T, Dean PB, Aro HT, Ahonen A, Nikkanen V. Incorporation and clinical results of large allografts of the extremities and pelvis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;307:200–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrington ED, Smith WJ, Chambers HG, Bucknell AL, Davino NA. Complications of iliac crest bone graft harvesting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329:300–309. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banwart JC, Asher MA, Hassanein RS. Iliac crest bone graft harvest donor site morbidity: a statistical evaluation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:1055–1060. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199505000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capanna R, Dal Monte A, Gitelis S, Campanacci M. The natural history of unicameral bone cyst after steroid injection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;166:204–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang CH, Stanton RP, Glutting J. Unicameral bone cysts treated by injection of bone marrow or methylprednisolone. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:407–412. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B3.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho HS, Oh JH, Kim HS, Kang HG, Lee SH. Unicameral bone cysts: a comparison of injection of steroid and grafting with autologous bone marrow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:222–226. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Docquier PL, Delloye C. Treatment of aneurysmal bone cysts by introduction of demineralized bone and autogenous bone marrow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2253–2258. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebraheim NA, Elgafy H, Xu R. Bone-graft harvesting from iliac and fibular donor sites: techniques and complications. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9:210–218. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200105000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, Malawar M, Pritchard DJ. A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;286:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernyhough JC, Schimandle JJ, Weigel MC, Edwards CC, Levine AM. Chronic donor site pain complicating bone graft harvesting from the posterior iliac crest for spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992;17:1474–1480. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199212000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gitelis S, Piasecki P, Turner T, Haggard W, Charters J, Urban R. Use of a calcium sulfate-based bone graft substitute for benign bone lesions. Orthopedics. 2001;24:162–166. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20010201-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goulet JA, Senunas LE, DeSilva GL, Greenfield ML. Autogenous iliac crest bone graft: complications and functional assessment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;339:76–81. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199706000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashemi-Nejad A, Cole WG. Incomplete healing of simple bone cysts after steroid injections. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:727–730. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B5.7825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirata M, Murata H, Takeshita H, Sakabe T, Tsuji Y, Kubo T. Use of purified beta-tricalcium phosphate for filling defects after curettage of benign bone tumours. Int Orthop. 2006;30:510–513. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0156-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanellopoulos AD, Yiannakopoulos CK, Soucacos PN. Percutaneous reaming of simple bone cysts in children followed by injection of demineralized bone matrix and autologous bone marrow. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:671–675. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000164874.36770.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly CM, Wilkins RM. Treatment of benign bone lesions with an injectable calcium sulfate-based bone graft substitute. Orthopedics. 2004;27(1 suppl):s131–s135. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20040102-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly CM, Wilkins RM, Gitelis S, Hartjen C, Watson JT, Kim PT. The use of a surgical grade calcium sulfate as a bone graft substitute: results of a multicenter trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;382:42–50. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Killian JT, Wilkinson L, White S, Brassard M. Treatment of unicameral bone cyst with demineralized bone matrix. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:621–624. doi: 10.1097/00004694-199809000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kose N, Gokturk E, Turgut A, Gunal I, Seber S. Percutaneous autologous bone marrow grafting for simple bone cysts. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1999;58:105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee GH, Khoury JG, Bell JE, Buckwalter JA. Adverse reactions to OsteoSet bone graft substitute, the incidence in a consecutive series. Iowa Orthop J. 2002;22:35–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumine A, Kusuzaki K, Matsubara T, Okamura A, Okuyama N, Miyazaki S, Shintani K, Uchida A. Calcium phosphate cement in musculoskeletal tumor surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:212–220. doi: 10.1002/jso.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirzayan R, Panossian V, Avedian R, Forrester DM, Menendez LR. The use of calcium sulfate in the treatment of benign bone lesions: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:355–358. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B3.11288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson PA, Wray AC. Natural history of posterior iliac crest bone graft donation for spinal surgery: a prospective analysis of morbidity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1473–1476. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200107010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rougraff BT. Bone graft alternatives in the treatment of benign bone tumors. Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:505–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rougraff BT, Kling TJ. Treatment of active unicameral bone cysts with percutaneous injection of demineralized bone matrix and autogenous bone marrow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:921–929. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sasso RC, LeHuec JC. Spine Interbody Research Group. Iliac crest bone graft donor site pain after anterior lumbar interbody fusion: a prospective patient satisfaction outcome assessment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(suppl):S77–S81. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000112045.36255.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schindler OS, Cannon SR, Briggs TW, Blunn GW. Composite ceramic bone graft substitute in the treatment of locally aggressive benign bone tumours. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2008;16:66–74. doi: 10.1177/230949900801600116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skaggs DL, Samuelson MA, Hale JM, Kay RM, Tolo VT. Complications of posterior iliac crest bone grafting in spine surgery in children. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2400–2402. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200009150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sung AD, Anderson ME, Zurakowski D, Hornicek FJ, Gebhardt MC. Unicameral bone cyst: a retrospective study of three surgical treatments. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2519–2526. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0407-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner TM, Urban RM, Gitelis S, Kuo KN, Andersson GB. Radiographic and histologic assessment of calcium sulfate in experimental animal models and clinical use as a resorbable bone-graft substitute, a bone-graft expander, and a method for local antibiotic delivery: one institution’s experience. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(suppl 2, pt 1):8–18. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200100021-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urban RM, Turner TM, Hall DJ, Infanger S, Cheema N, Lim TH. Healing of large defects treated with calcium sulfate pellets containing demineralized bone matrix particles. Orthopedics. 2003;26(5 suppl):s581–s585. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20030502-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urban RM, Turner TM, Hall DJ, Inoue N, Gitelis S. Increased bone formation using calcium sulfate-calcium phosphate composite graft. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;457:110–117. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318059b902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright JG, Yandow S, Donaldson S, Marley L. Simple Bone Cyst Trial Group. A randomized clinical trial comparing intralesional bone marrow and steroid injections for simple bone cysts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:722–730. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]