Abstract

Background

Polyethylene wear is often cited as the cause of failure of TKA. Rotating platform (RP) knees show notable surface damage on the rotating surface raising concerns about increased wear compared to fixed bearing inserts.

Questions/purposes

We therefore addressed the following questions: Is wear in RP inserts increased compared to that in fixed bearing inserts? Does the surface roughness of the tibial tray have a measurable impact on in vivo wear of modular knees? And does wear rate differ between posterior stabilized (PS) and cruciate retaining (CR) knees?

Methods

We compared wear in two series of retrieved knee devices: 94 RP mobile bearings with polished cobalt-chrome (CoCr) trays and 218 fixed bearings with both rough titanium (Ti) and polished CoCr trays. Minimum implantation time was 0.4 months (median, 36 months; range, 0.4–124 months) and 2 months (median, 72 months; range, 2–179 months) for the RP and fixed bearing series, respectively.

Results

Wear rate was lower for RP inserts than for fixed bearing inserts. Backside wear rate was lower for fixed bearing inserts mated to polished CoCr trays than for inserts from rough Ti trays. Inserts against polished trays (RP or fixed bearing) showed no increase in wear rate increase over time. Wear rate of PS knees was similar to that of CR knees.

Conclusions

We found mobile bearing knees have reduced wear rate compared to fixed bearings, likely due to the polished CoCr tibial tray surface. Fixed bearing inserts in polished CoCr trays wear less than their counterparts in rough Ti trays, and the wear rate of inserts from polished CoCr trays does not appear to increase with time.

Introduction

Polyethylene wear frequently is cited by orthopaedic surgeons as the cause of failure and revision of knee arthroplasty devices [27, 35, 38]. In modular knee bearings, backside wear can produce small debris particles of the size implicated as the cause of osteolysis [30, 33, 38]. Previous studies have documented the effect of backside wear on the locking mechanisms for different modular knee systems, leading to increased bearing motion within the tray and resultant bearing wear [11, 17, 31, 32].

Mobile bearing knees are an appealing approach to tibial loosening in fixed bearing knees presumably related to rotational malalignment [9, 15, 16]. Knee arthroplasties with rotating tibial platforms (RPs) represent one approach for mobile bearing devices [6]. A potential disadvantage of the RP knees is the addition of the large backside articular surface that accommodates tibiofemoral rotation. The concerns about backside wear being a source of wear debris in knees extend to RP knees and warrant careful study of their wear performance.

Recent reports on clinical wear performance of RPs that are based on visual assessment of damage to bearing surfaces have highlighted concern about backside wear based on the surface features seen [20, 22, 28]. Accurate measurement of actual material loss from retrieved knee bearings presents difficult challenges because gravimetric methods are not useful with retrievals and unworn reference dimensions are often unavailable. Through our ongoing retrieval collaboration that receives devices from many surgeons and institutions, we now have a series of knee retrievals for which as-manufactured dimensions are available and quantitative measurements of true knee wear can be determined.

We therefore addressed the following questions: (1) Is wear associated with RP mobile bearing inserts decreased compared to that of fixed bearing inserts? (2) Does the surface roughness of the tibial tray have a measurable impact on in vivo wear of modular knees? And (3) does wear rate differ between posterior stabilized (PS) knees and cruciate retaining (CR) knees?

Materials and Methods

This study is based on explanted devices sent for evaluation to an established retrieval laboratory open to submittal from all surgeons and centers. We investigated two series of retrieved knee devices: (1) 94 Sigma® RP mobile bearing knees (DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc, a Johnson and Johnson company, Warsaw, IN, USA) submitted by 26 surgeons between December 2002 and February 2011; and (2) 218 Sigma® fixed bearing knees (DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc) submitted by 46 surgeons between January 2003 and February 2011 (Table 1). The RP series included 27 inserts of the curved design (which is CR) and 67 inserts of the PS design. The fixed bearing series included 19 inserts with the posterior lipped design (which is CR), 85 of the curved design (CR), and 77 of the PS design. The fixed bearing knee series was also partitioned into 181 knees with rough (grit-blasted finish) titanium (Ti) trays (median implantation time, 81 months) and 37 with polished cobalt-chrome (CoCr) trays (median implantation time, 17 months). For the RP series, minimum implantation time was 0.4 months (median, 36 months; range, 0.4–124 months). For the fixed bearing series, minimum implantation time was 2.1 months (median, 72 months; range, 2.1–179 months). The polyethylene in the Sigma® fixed bearing series in rough Ti trays and the Sigma® RP series were made from compression-molded sheet stock of 1020 UHMWPE resin, gamma irradiated at approximately 4 Mrad and barrier packaged. The Sigma® fixed bearing series in polished CoCr trays had 10 inserts made from this same compression-molded sheet stock of 1020 UHMWPE resin, gamma irradiated at approximately 4 Mrad and barrier packaged, and 27 inserts made from compression-molded sheet stock of 1020 UHMWPE resin, gamma irradiated at approximately 5 Mrad, heated to melt temperature, and sterilized with gas plasma. We included all explanted bearings of the Sigma® and Sigma® RP designs received during the study period in this study except those that had been autoclaved.

Table 1.

Knee retrieval series

| Insert type | Number of retrievals | In vivo duration (months) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Ti tray | CoCr tray | Median | Range | |

| Sigma® RP | |||||

| Curved (CR) | 27 | 27 | 37 | 0.4–109 | |

| PS | 67 | 67 | 34 | 2–124 | |

| Total RPs | 94 | 94 | 36 | 0.4–124 | |

| Sigma® fixed bearing Ti trays | |||||

| Posterior lipped (CR) | 19 | 19 | 72 | 10–164 | |

| Curved (CR) | 85 | 85 | 90 | 6–179 | |

| PS | 77 | 77 | 76 | 2–164 | |

| Total Ti tray | 181 | 181 | 81 | 2–179 | |

| Sigma® fixed bearing CoCr trays | |||||

| Posterior lipped (CR) | 4 | 4 | 12 | 4–24 | |

| Curved (CR) | 12 | 12 | 16 | 5–25 | |

| PS | 21 | 21 | 24 | 4–47 | |

| Total CoCr tray | 37 | 37 | 17 | 4–47 | |

| Total fixed bearing | 218 | 181 | 37 | 72 | 2–179 |

Ti = titanium; CoCr = cobalt-chrome; RP = rotating platform; CR = cruciate retaining; PS = posterior stabilized.

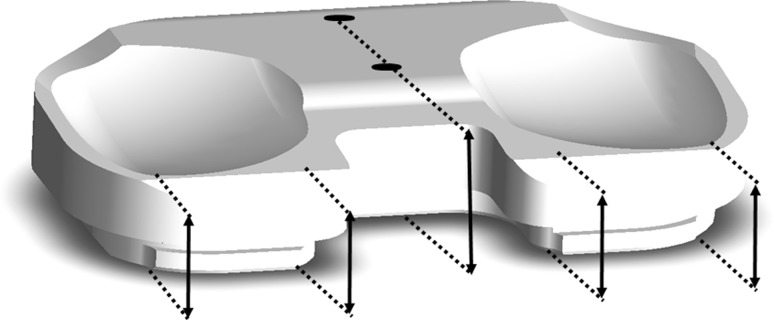

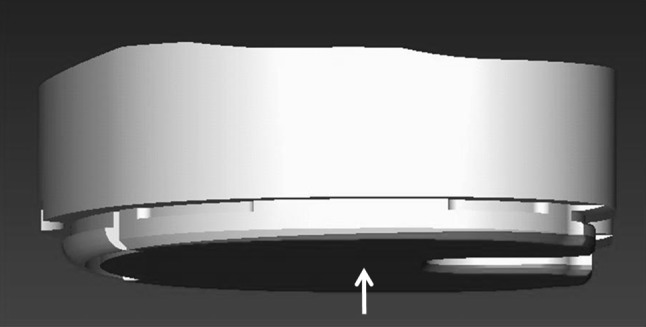

We estimated the total through-thickness wear of each insert by measuring the minimum thicknesses within the medial and lateral condylar bearing areas using a dial indicator with 3-mm-radius ball end contacts (Fig. 1). Wear penetration was calculated by subtracting the measured thickness dimension from the as-manufactured dimension. A composite through-thickness wear for each device was determined by the average of the wear on the medial and lateral bearing areas.

Fig. 1.

Through-thickness wear of each insert (RP shown here) was determined by measuring the thickness of the retrieved knee bearings with a dial indicator at their thinnest point on both the medal and lateral condylar bearing areas, respectively (approximate locations indicated by arrows), and comparing those dimensions to the specified minimum thickness from the manufacturer’s design drawings.

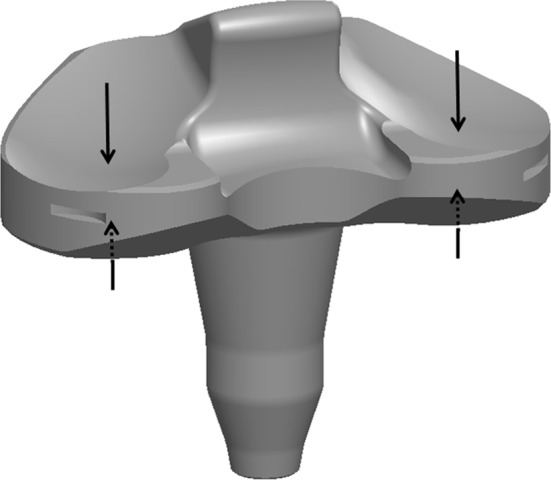

On the fixed bearing inserts, an estimate of backside wear was possible because their design incorporated topside datum surfaces that normally remain undamaged and unworn in vivo. The RP bearings in this study did not incorporate any flat topside datum surfaces so no reliable measurement of backside wear could be made. We measured the thickness of the polyethylene inserts from topside reference points to the bottom surface using dial calipers and a dial indicator (Fig. 2). Design drawings were used to obtain the nominal initial thickness at the corresponding measurement points, and backside wear depth was estimated by subtracting measured thickness from design thickness. The composite backside wear depth for an insert was calculated by linear interpolation of the wear depth at each measurement point to the center point of the backside area. To estimate the volume of backside wear, the composite backside wear depth was multiplied by the backside surface area (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

For backside wear estimates on Sigma® fixed bearing inserts, thickness dimensions were taken at reference points indicated by the arrows on this schematic, which typically show no proximal surface wear, with care taken to measure perpendicular to the surface planes.

Fig. 3.

Composite backside wear depth of fixed bearing inserts was determined taking multiple measurements and interpolating to wear at the center of insert (arrow). Inserts in rough Ti trays typically demonstrated a backside wear wedge, with more wear posteriorly and medially. Backside wear volume was calculated by multiplying the composite wear depth by the backside area.

We measured five nonimplanted fixed bearing inserts and one nonimplanted RP insert to confirm reference dimensions.

We determined the dependence of wear rate on in vivo duration for each series by calculating Spearman’s rho. The test for differences in medial and lateral wear was determined using the paired-samples t-test with a CI of 95%. We determined differences in wear rates between the RP and fixed bearing knees, between fixed bearings from Ti trays and fixed bearings from CoCr trays, and between CR and PS bearings using the independent-samples t-test for equality of means with a CI of 95% and equal variances assumed. The statistical package used was SPSS® Version 19 (IBM Corp, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 32 measurements on nonimplanted inserts showed a mean deviation from nominal thickness of −0.021 mm (SD, 0.055 mm; range, −0.152 to +0.076 mm). The manufacturing tolerance was 0.13 mm for all thickness measurements employed for this study.

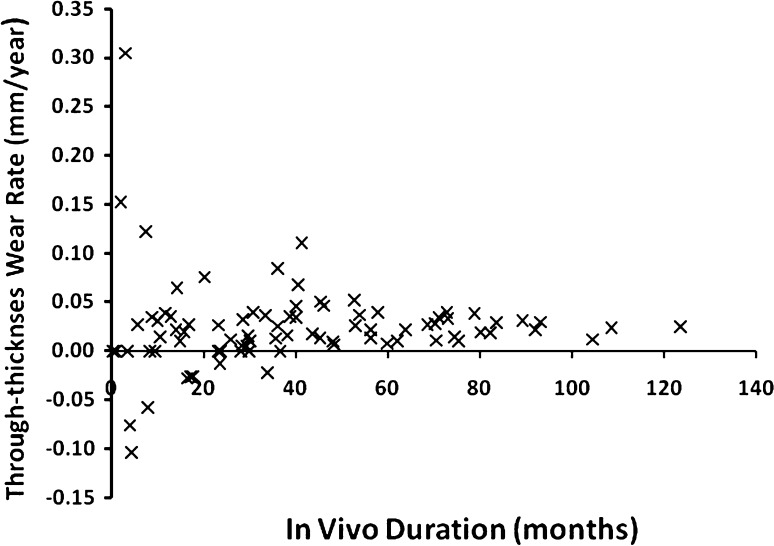

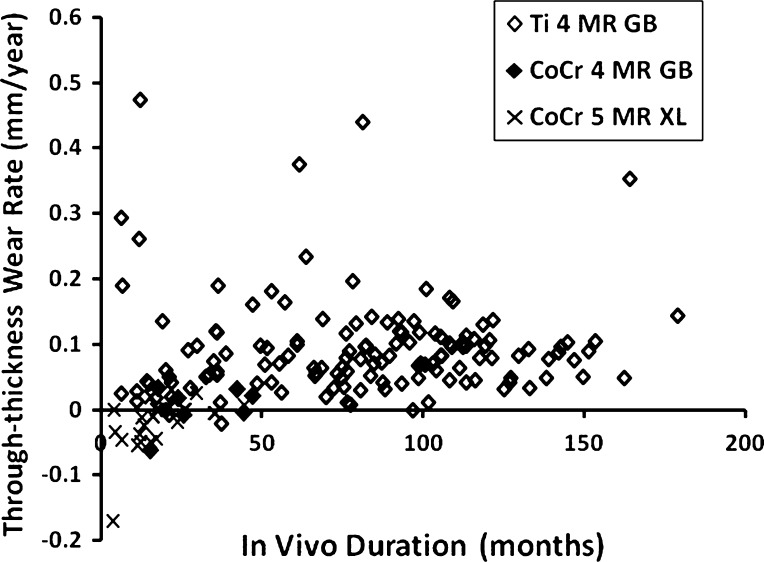

The RP inserts had a lower (p = 0.03) wear rate than the fixed bearing inserts (0.04 versus 0.07 mm/year) (Table 2). The wear rate of the RPs (Fig. 4) did not depend on in vivo duration (Spearmans’s rho = 0.176, p = 0.11), in contrast to the fixed bearings (Fig. 5), which showed an increasing wear rate with increasing in vivo duration (Spearman’s rho = 0.469, p < 0.001) (Table 3). The RP bearings showed no difference (p = 0.72) in medial and lateral wear, while the fixed bearing inserts showed greater (p < 0.001) wear on the medial side (Table 4).

Table 2.

Summary of wear measurements

| Device type | Number of retrievals | Backside wear | Through-thickness wear | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth (mm) | Rate (mm/year) | Volumetric rate (mm3/year) | Depth (mm) | Rate (mm/year) | ||

| Sigma® RP | ||||||

| Curved (CR) | 27 | 0.08 ± 0.08 | 0.06 ± 0.26 | |||

| PS | 67 | 0.08 ± 0.10 | 0.03 ± 0.05 | |||

| Total RPs | 94 | NA | NA | NA | 0.08 ± 0.09 | 0.04 ± 0.15 |

| Sigma® fixed bearing Ti trays | ||||||

| Posterior lipped (CR) | 19 | 0.10 ± 0.11 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 31 ± 38 | 0.48 ± 0.33 | 0.08 ± 0.04 |

| Curved (CR) | 85 | 0.24 ± 0.26 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 65 ± 78 | 0.65 ± 0.61 | 0.08 ± 0.08 |

| PS | 77 | 0.17 ± 0.27 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 42 ± 53 | 0.68 ± 0.76 | 0.10 ± 0.08 |

| Total Ti tray | 181 | 0.20 ± 0.23 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 51 ± 66 | 0.65 ± 0.66 | 0.09 ± 0.08 |

| Sigma® fixed bearing CoCr trays | ||||||

| Posterior lipped (CR) | 4 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 22 ± 26 | −0.003 ± 0.04 | −0.008 ± 0.03 |

| Curved (CR) | 12 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 38 ± 44 | −0.02 ± 0.04 | −0.02 ± 0.03 |

| PS | 21 | 0.005 ± 0.04 | −0.003 ± 0.03 | −9 ± 42 | 0.003 ± 0.04 | −0.01 ± 0.05 |

| Total CoCr tray | 37 | 0.01 ± 0.23 | 0.006 ± 0.02 | 10 ± 46 | −0.005 ± 0.04 | −0.01 ± 0.04 |

| Total fixed bearings | 218 | 0.17 ± 0.24 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 44 ± 65 | 0.52 ± 0.65 | 0.07 ± 0.08 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD; RP = rotating platform; CR = cruciate retaining; PS = posterior stabilized; Ti = titanium; CoCr = cobalt-chrome; NA = not applicable.

Fig. 4.

Through-thickness total wear penetration rate (flexion surface and rotation surface) of Sigma® RP bearings is plotted versus in vivo duration. The wear rate does not depend on in vivo duration.

Fig. 5.

Through-thickness total wear penetration rate versus in vivo duration is shown for the Sigma® fixed bearing inserts, including those in rough Ti trays with 4-Mrad gamma-irradiated and barrier-packaged material (Ti 4 MR GB) and those in polished CoCr trays with (1) 4-Mrad gamma-irradiated and barrier-packaged material (CoCr 4 MR GB) and (2) 5-Mrad gamma-irradiated and gas plasma-sterilized material (CoCr 5 MR XL). Fixed bearings showed an increasing wear rate with increasing in vivo duration.

Table 3.

Summary of statistical comparisons of total through-thickness wear rates

| Wear rate | In vivo duration | RP through-thickness wear rate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho | p value | p value | |

| RP through-thickness wear rate | 0.176 | 0.11 | |

| Fixed bearing through-thickness wear rate | 0.469 | < 0.001 | 0.03 |

| Fixed bearing Ti tray wear rate | 0.494 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Fixed bearing CoCr tray wear rate | 0.037 | 0.83 | 0.04 |

Correlation of wear rates (Column 1) to in vivo duration is shown in Column 2; results of t-test for equality of means between wear rates (Column 1) to RP wear rate are given in Column 3; RP = rotating platform; Ti = titanium; CoCr = cobalt-chrome.

Table 4.

Summary of t-test results of comparisons of wear rates

| Comparison | p value |

|---|---|

| Fixed bearing Ti tray vs CoCr tray | |

| Backside wear depth | < 0.001 |

| Backside linear wear rate | < 0.001 |

| Backside volumetric wear rate | < 0.001 |

| RP medial versus lateral wear | 0.72 |

| Fixed bearing medial versus lateral wear | < 0.001 |

| RP CR versus PS wear rate | 0.35 |

| Fixed bearing CR versus PS wear rate | 0.90 |

Ti = titanium; CoCr = cobalt-chrome; RP = rotating platform; CR = cruciate retaining; PS = posterior stabilized.

Comparing fixed bearing inserts from the different tray surfaces showed the inserts in polished CoCr trays had better wear performance by several measures: mean depth of backside wear (0.01 versus 0.20 mm, p < 0.001), mean backside wear rate (0.006 versus 0.02 mm/year, p < 0.001), and volumetric wear rate (10 versus 51 mm3/year, p < 0.001). Separating the fixed bearings by tray type made a noticeable difference in the mobile bearing-fixed bearing comparison: the fixed bearing cohort from the rough Ti trays showed an even larger (p = 0.001) difference from RPs (0.09 versus 0.04 mm/year), while the fixed bearing inserts from polished CoCr trays showed a lower (p = 0.04) wear rate than the RPs (−0.01 versus 0.04 mm/year). The backside wear rate of the inserts from CoCr trays did not increase with in vivo duration (Spearman’s rho = 0.037, p = 0.83), whereas the wear rate of inserts from rough Ti trays did (Spearman’s rho = 0.494, p < 0.001).

The comparison between CR and PS knees did not show a difference in wear rate. In the RP series, the mean wear rate was 0.06 mm/year for CR inserts and 0.03 mm/year for PS inserts (p = 0.35). For the fixed bearing series, the mean through-thickness wear rate was 0.07 mm/year for both CR and PS knees (p = 0.90).

Discussion

Many published studies on clinical performance of knees are based on visual assessment of the surfaces of explanted devices [14, 21, 25, 26, 39] and provide important information about in vivo kinematics, impingement, debris, modes of material wear, and other aspects of bearing performance. Measuring actual wear (material loss) from clinical knee retrievals is challenging, in large part because an accurate unworn reference (either gravimetric or dimensional) is usually not known. Our objectives were to contribute quantitative wear measurements from retrieved knee bearings to answer whether RP mobile bearings wear more than fixed bearings in vivo, tibial tray roughness has a measurable impact on backside wear, and there is a difference in wear between CR and PS inserts.

Readers should be aware of the limitations of the study. First, we considered a limited series of retrieved bearings of two designs. Our findings might not apply to other designs. Second, the in vivo duration is longer for the fixed bearing series than for the RP series (179 versus 124 months). In consideration of this difference, wear measurements were presented in terms of both depth of wear and wear rate (normalized for in vivo duration) and conclusions are based only on wear rate. Third, the RP wear measurements and the corresponding through-thickness measurements of fixed bearing inserts represent total wear on both the top and bottom articulating surfaces plus other deformation processes such as creep and pitting. Therefore, the reported wear measurements should be considered a conservatively high value of insert thinning due to abrasive/adhesive wear. We report an estimate of wear volume only for backside wear, for which the area of the worn surface could be accurately measured, and therefore direct comparisons with other studies should be made on the basis of backside-only wear volume.

Our findings indicate the additional articulating surface of the RPs did not increase total wear penetration rate on the inserts compared to fixed bearing inserts. This finding does not support the concern raised by the damaged appearance of the rotation surface of retrieved mobile bearing knees [20, 22, 28] (Table 5). The lack of wear bias to the medial side is consistent with other reports of measured wear of mobile bearings [1, 18, 24] (Table 5) but is distinct from our fixed bearing results and those of other reports [12, 36] (Table 6). The RP wear rate of 0.04 mm/year in our study is lower than the 0.09 mm/year reported by Kop and Swarts [24] for relatively small series of both LCS-RP® and AP Glide® inserts and by Atwood et al. [1] for a series of 100 LCS-RP® inserts (Table 5). It is notable, in the study of Atwood et al. [1], the wear rate for in vivo duration of more than 2 years was 1/3 of the series average. In our study, the wear rate of the RPs was not dependent on vivo duration, in clear contrast to the wear rate of the fixed bearing series, which increased with in vivo duration. The wear rate of the fixed bearing inserts was within the range of other published results, which range from 0.0041 mm/year for a study based on erasure of engraved backside lettering [13] to 0.35 mm/year based on through-thickness measurement on a variety of designs [3] (Table 6).

Table 5.

Comparison of mobile bearing knee wear assessments from other studies and our study

| Study | Bearing type | Implant | Number | In vivo duration (months)* | Assessment method | Wear rate | Notes/Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kop and Swarts [24] | AP mobile | AP Glide® | 10 | 31 (10–51) | CMM, with mathematic reconstruction of unworn surfaces Visual rating of damage modes (0–3) |

0.09 mm/year 80 mm3/year (wear volume) |

Same rates for both designs No medial-lateral wear bias |

| RP | LCS® | 7 | 36 (9–70) | ||||

| Atwood et al. [1] | RP | LCS® | 100 | 41 (2–170) | Through-thickness measurement Backside surface only measurement |

0.09 mm/year 0.06 mm/year |

High initial wear rate Lower long-term rate No medial-lateral wear bias 59% had < 2 years’ duration |

| Engh et al. [18] | Mobile | LCS® MB | 23 | 29 (1–102) | Through-thickness measurement (n = 12) Visual rating of damage modes (0–3) |

0.047 mm/year | Surface damage did not reflect material lost |

| Garcia et al. [20] | RP | LCS® | 32 | 30 (0.3–191) | Visual rating of damage modes (0–3) | NA | No medial-lateral difference Damage increased with duration Damage decreased with weight and BMI Damage higher in loose knees |

| RP | Sigma® | 8 | |||||

| Kendrick et al. [23] | Mobile | Oxford® Uni | 47 | 101 (13–200) | Measured bearing thickness | 0.07 mm/year | Highest wear with extraarticular impingement |

| Lu et al. [28] | RP | LCS® | 15 | 121 (48–162) | Visual rating of damage modes (0–3) | NA | Greater damage on top surface of fixed bearings but backside of RPs RP damage did not correlate to duration or BMI RP top damage correlated to back |

| Kelly et al. [22] | RP | LCS® | 12 | 36 (10–144) | Visual rating of damage modes (0–3) | NA | Backside damage correlated to duration; top surface does not Damage does not correlate to BMI Damage higher with osteolysis |

| Sigma® | 36 | ||||||

| Current study | RP | Sigma® RP | 94 | 39 (0.4–124) | Through-thickness measurements | 0.04 mm/year | No medial wear bias; wear rate does not increase with duration No wear difference between CR and PS inserts |

* Values are expressed as mean, with range in parentheses; RP = rotating platform; CMM = coordinate measuring machine; CR = cruciate retaining; PS = posterior stabilized; NA = not available.

Table 6.

Comparison of fixed bearing knee wear assessments from other studies and our study

| Study | Bearing type | Implant | Number | In vivo duration (months)* | Assessment method | Wear rate | Notes/Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benjamin et al. [3] | Fixed | AMK® + PFC® | 24 | 68 (9–132) | Through-thickness measurement Laser scan for volume Visual rating of damage pattern (1–6) |

0.35 mm/year 794 mm3/year (wear volume) |

Wear rates decreased with duration |

| Synatomic | 9 | ||||||

| Fixed | Synatomic | 9 | |||||

| Li et al. [26] | Fixed | AMK®, PFC® Genesis, IB-II |

55 | 1–73 | Visual rating of damage modes (0–3) Removal of stamped markings Extrusions into screw holes |

87 mg/year | Wear rate estimated for one insert only |

| Surace et al. [36] | Fixed | MG® | 11 | 64 (4–156) | Visual rating of damage modes (0–3) Extruded pegs with optical zoom |

Peg heights 0 to 0.317 mm Pegs indicate most wear posterior, medial |

|

| Fixed | MG II® | 14 | |||||

| Conditt et al. [12] | Fixed | AMK® | 15 | 91 (36–146) | Linear laser scans of backside, 3D computer reconstruction for volume | 138 mm3/year (wear volume) | Significantly more wear medially |

| Crowninshield et al. [13] | Fixed | NexGen® | 43 | 33 (2–80) | Visual rating of damage modes (0–3) Profilometry of engraved lettering |

0.0041 mm/year | Damage modes: no correlation with duration Backside wear has partial association with duration |

| Engh et al. [18] | Fixed | AMK® | 31 | 32 (1–141) | Through-thickness measurement (n = 6) Visual rating of damage modes (0–3) |

0.047 mm/year | Surface damage did not reflect material lost |

| Current study | Fixed | Sigma® | 218 | 65 (2.1–179) | Through-thickness and backside measurements Backside wear volume calculated |

0.07 mm/year (total) 0.02 mm/year (backside) 44 mm3/year (wear volume) |

Medial wear bias; wear rate increases with duration No wear difference between CR and PS inserts |

* Values are expressed as mean, with range in parentheses; CR = cruciate retaining; PS = posterior stabilized.

The lower wear rate for the fixed bearing inserts in polished CoCr trays compared with inserts in rough Ti trays confirms findings from in vitro wear studies [4, 19] and retrieval analysis [10]. A further indication of the difference in wear performance is that inserts from Ti trays showed wear rate increasing with in vivo duration, while the inserts from polished CoCr trays did not. Increasing backside wear rate in fixed bearings would be expected due to wear of the insert locking mechanism, a process that has been reported in previous studies of modular fixed bearing knees [11, 31].

Our observations suggest decreasing the roughness of the modular tray has a notable impact on clinical wear. This is demonstrated by the RP inserts, which are free to rotate on a polished tray yet showed lower wear rate than the fixed bearings taken as a whole. It is demonstrated further within the fixed bearing series, which showed a wear rate for inserts from polished CoCr trays lower than both the fixed bearing inserts from rough Ti trays and the RP inserts. The findings suggest limiting insert-to-tray motion alone is not fully effective in reducing wear; optimizing the metal counterface and the relative motion is important. Although there is widely reported evidence of substantial motion of RPs relative to the trays [20, 22, 23, 28], the central post constrains the relative motion to be unidirectional. The backside surface of fixed bearing knees experiences much less extensive motion, but it is multidirectional. Increased wear of polyethylene under conditions of multidirectional motion has been documented by in vitro wear studies [4, 5, 7, 29, 37].

We found no difference in measured wear rate between CR and PS knees. An important design premise of PS knees is that kinematics can be maintained while tibiofemoral surface area is increased and contact stress is accordingly decreased [2, 6, 8, 34]. One hypothesis for the lack of differential performance is that the increased conformity also increases tibiofemoral transmission of torque, which drives rotational motion at the insert-tray interface. Progressive wear of a fixed bearing locking mechanism and a rough tray counterface would be expected to result in increasing backside wear rate, which is what we saw in the fixed bearings from Ti trays. Although the in vivo duration of the CoCr fixed bearings is shorter, that design appears to accommodate backside motion with less insert wear than with the rough Ti counterface.

In summary, we found the wear rate of RP inserts was less than that of fixed bearing inserts, which is in contrast to the indications from retrieval studies based on surface damage assessment. The wear rate of fixed bearing inserts in polished CoCr trays was less than their counterparts in rough Ti trays and was less than the RP inserts. The wear rate of PS and CR inserts was not different. Our findings indicate a polished tray counterface reduces insert wear and the wear rate of inserts against a polished CoCr tray does not appear to increase over time.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the surgeons who have collaborated with our institutions by sending retrieved devices for analysis. We also thank DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc, for providing the design and manufacturing data for the implants studied in this investigation, without which this type of clinical retrieval analysis is not possible.

Footnotes

One of the authors (DJB) certifies that he has or may receive payments or benefits, in any one year, an amount in excess of $100,000 from a commercial entity (DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc, a Johnson and Johnson company, Warsaw, IN, USA) related to this work; one of the authors (MBM) certifies that he has or may receive payments or benefits, in any one year, an amount in excess of $10,000 from a commercial entity (DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc) related to this work; one of the authors (JPC) is a consultant from a commercial entity (DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc) related to this work; the institution of two of the authors (MBM, JPC) has received funding from a commercial entity (DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc) related to this work.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

This work was performed at the Dartmouth Biomedical Engineering Center, Hanover, NH, USA.

References

- 1.Atwood SA, Currier JH, Mayor MB, Collier JP, Citters DW, Kennedy FE. Clinical wear measurement on low contact stress rotating platform knee bearings. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DL, Rawlinson JJ, Burstein AH, Ranawat CS, Flynn WF. Stresses in polyethylene components of contemporary total knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;317:76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin J, Szivek J, Dersam G, Persselin S, Johnson R. Linear and volumetric wear of tibial inserts in posterior cruciate-retaining knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:131–138. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200111000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billi F, Sangiorgio SN, Aust S, Ebramzadeh E. Material and surface factors influencing backside fretting wear in total knee replacement tibial components. J Biomech. 2010;43:1310–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bragdon CR, O’Connor DO, Lowenstein JD, Jasty M, Syniuta WD. The importance of multidirectional motion on the wear of polyethylene. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 1996;210:157–165. doi: 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1996_210_408_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buechel FF. Mobile-bearing knee arthroplasty: rotation is our salvation! J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burroughs BR, Blanchet TA. Factors affecting the wear of irradiated UHMWPE. Tribol Trans. 2001;44:215–223. doi: 10.1080/10402000108982451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callagan JJ, Liu SS. Posterior cruciate ligament-substituting total knee arthroplasty. In: Scott WN, editor. Surgery of the Knee. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 1531–1557. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng CK, Huang CH, Liau JJ, Huang CH. The influence of surgical malalignment on the contact pressures of fixed and mobile bearing knee prostheses—a biomechanical study. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2003;18:231–236. doi: 10.1016/S0268-0033(02)00189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collier MB, Engh CA, McAuley JP, Ginn SD, Engh GA. Osteolysis after total knee arthroplasty: influence of tibial baseplate surface finish and sterilization of polyethylene insert—findings at five to ten years postoperatively. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2702–2708. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conditt MA, Stein JA, Noble PC. Factors affecting the severity of backside wear of modular tibial inserts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:305–311. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200402000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conditt MA, Thompson MT, Usrey MM, Ismaily SK, Noble PC. Backside wear of polyethylene tibial inserts: mechanism and magnitude of material loss. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:326–331. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.01308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowninshield RD, Wimmer MA, Jacobs JJ, Rosenberg AG. Clinical performance of contemporary tibial polyethylene components. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:754–761. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuckler JM, Lemons J, Tamarapalli JR, Beck P. Polyethylene damage on the nonarticular surface of modular total knee prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;410:248–253. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000063794.32430.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dennis DA, Komistek RD. Mobile-bearing total knee arthroplasty: design factors in minimizing wear. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;452:70–77. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238776.27316.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Lima DD, Trice M, Urquhart AG, Colwell CW. Tibiofemoral conformity and kinematics of rotating-bearing knee prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;386:235–242. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200105000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engh GA, Lounici S, Rao AR, Collier MB. In vivo deterioration of tibial baseplate locking mechanisms in contemporary modular total knee components. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1660–1665. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200111000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engh GA, Zimmerman RL, Parks NL, Engh CA. Analysis of wear in retrieved mobile and fixed bearing knee inserts. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher J, McEwen H, Tipper J, Jennings L, Farrar R, Stone M, Ingham E. Wear-simulation analysis of rotating-platform mobile-bearing knees. Orthopedics. 2006;29:S36–S41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia RM, Kraay MJ, Messerschmitt PJ, Goldberg VM, Rimnac CM. Analysis of retrieved ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene tibial components from rotating-platform total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hood RW, Wright TM, Burstein AH. Retrieval analysis of total knee prostheses: a method and its application to 48 total condylar prostheses. J Biomed Mater Res. 1983;17:829–842. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820170510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly NH, Fu RH, Wright TM, Padgett DE. Wear damage in mobile-bearing TKA is as severe as that in fixed-bearing TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:123–130. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1557-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendrick BJ, Longino D, Pandit H, Svard U, Gill HS, Dodd CA, Murray DW, Price AJ. Polyethylene wear in Oxford unicompartmental knee replacement: a retrieval study of 47 bearings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:367–373. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B3.22491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kop AM, Swarts E. Quantification of polyethylene degradation in mobile bearing knees—a retrieval analysis of the anterior-posterior-glide (APG) and rotating platform (RP) low contact stress (LCS) knee. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:364–370. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landy MM, Walker PS. Wear of ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene components of 90 retrieved knee prostheses. J Arthroplasty. 1988;3:S73–S85. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(88)80013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li S, Scuderi G, Furman BA, Bhattacharyya S, Schmieg JJ, Insall JN. Assessment of backside wear from the analysis of 55 retrieved tibial inserts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:75–82. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lonner JH, Siliski JM, Scott RD. Prodromes of failure in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:488–492. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(99)90106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu YC, Huang CH, Chang TK, Ho FY, Cheng CK, Huang CH. Wear-pattern analysis in retrieved tibial inserts of mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing total knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:500–507. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muratoglu OK, Bragdon CR, O’Connor DO, Jasty M, Harris WH, Gul R, McGarry F. Unified wear model for highly crosslinked ultra-high molecular weight polyethylenes (UHMWPE) Biomaterials. 1999;20:1463–1470. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muratoglu OK, Ruberti J, Melotti S, Spiegelberg SH, Greenbaum ES, Harris WH. Optical analysis of surface changes on early retrievals of highly cross-linked and conventional polyethylene tibial inserts. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:42–47. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parks NL, Engh GA, Topoleski LD, Emperado J. The Coventry Award. Modular tibial insert micromotion: a concern with contemporary knee implants. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;356:10–15. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199811000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao AR, Engh GA, Collier MB, Lounici S. Tibial interface wear in retrieved total knee components and correlations with modular insert motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1849–1855. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200210000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmalzried TP, Jasty M, Rosenberg A, Harris WH. Polyethylene wear debris and tissue-reactions in knee as compared to hip-replacement prostheses. J Appl Biomater. 1994;5:185–190. doi: 10.1002/jab.770050302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scuderi GR, Clarke HD. Cemented posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:7–13. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Surace MF, Berzins A, Urban RM, Jacobs JJ, Berger RA, Natarajan RN, Andriacchi TP, Galante JO. Coventry Award paper. Backsurface wear and deformation in polyethylene tibial inserts retrieved postmortem. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:14–23. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang A. A unified theory of wear for ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene in multi-directional sliding. Wear. 2001;248:38–47. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1648(00)00522-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wasielewski RC, Parks N, Williams I, Surprenant H, Collier JP, Engh G. Tibial insert undersurface as a contributing source of polyethylene wear debris. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;345:53–59. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199712000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright TM, Rimnac CM, Stulberg SD, Mintz L, Tsao AK, Klein RW, McCrae C. Wear of polyethylene in total joint replacements: observations from retrieved PCA knee implants. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;276:126–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]