Abstract

Background

A method for reducing the power of drug cues could help in treating drug abuse and addiction. Extinction has been used, with mixed success, in such an effort. Research with non-drug cues has shown that simultaneously presenting (compounding) those cues during extinction can enhance the effectiveness of extinction. The present study investigated whether this procedure could be used to similarly deepen the extinction of cocaine cues.

Methods

Rats were first trained to self-administer cocaine during tone, click, and light stimuli. Then, these stimuli were subjected to extinction in an initial phase where they were presented individually. In a second extinction phase, one of the auditory stimuli (counterbalanced) was compounded with the light. The other auditory stimulus continued to be presented alone. Rats were then given a week of rest in their homecages prior to testing for spontaneous recovery of cocaine seeking.

Results

The cue that was compounded with the light during the second phase of extinction training occasioned less spontaneous recovery of cocaine seeking than the cue that was always presented individually during extinction. Increasing the number of compound cue extinction sessions did not produce a greater deepened extinction effect.

Conclusions

The present study showed that simultaneously presenting already-extinguished cocaine cues during additional extinction training enhanced extinction. This extends the deepened extinction effect from non-drug cues to drug cues and further confirms predictions of error-correction learning theory. Incorporating deepened extinction into extinction-based drug abuse treatments could help to reduce the power of drug cues.

Keywords: extinction, drug cues, cocaine, self-administration, cue exposure, stimulus compounding, rats

1. Introduction

Drug cues play an important role in drug abuse and addiction (Childress et al., 1999; Grusser et al., 2004; Kosten et al., 2006; Sinha and Li, 2007; Volkow et al., 2006, 2008). Extinction has been used in efforts to break the association between cue and drug. The extinction-based treatment called cue-exposure therapy (Drummond et al., 1995) involves repeatedly presenting drug cues in the absence of the drug. Although a few studies have indicated that cue-exposure therapy may have some promise (e.g., Loeber et al., 2006; Rohsenow et al., 2001), in general, results have not been as encouraging as expected (for review see Conklin and Tiffany, 2002). Several investigators have suggested that extinction-based treatments could be improved by incorporating basic research findings on extinction (Bouton, 2002; Conklin and Tiffany, 2002; Havermans and Jansen, 2003).

Recent such research has shown that extinction can be enhanced by applying predictions of error-correction learning models. The Rescorla-Wagner model (Rescorla and Wagner, 1972; Wagner and Rescorla, 1972) is the earliest and most influential of a number of error-correction models of learning (e.g., Pearce and Hall, 1980; Mackintosh, 1975; Sutton and Barto, 1981). The validity and generality such models is supported by their ability to explain many phenomena, ranging from the basic acquisition of behavior to more complex outcomes such as blocking (Kamin, 1969). Learning, including that involved in extinction, is driven by the discrepancy between expectation and outcome, according to error-correction accounts. For example, early in extinction training a rat expects food when a previously-food-paired tone is presented. Because no food is delivered, there is a discrepancy (“prediction error”) between expectation and outcome. Extinction learning acts to correct this discrepancy by decreasing future expectation for food during the tone. After many extinction trials, the rat no longer expects food when the tone is presented. Thus, when food is not delivered, there is no longer a prediction error and no further extinction learning takes place.

Rescorla (2006) hypothesized that further extinction of already-extinguished cues might occur if expectation were temporarily restored during additional extinction trials. That is, re-introducing a prediction error during the non-reinforced presentation of previously extinguished cues should deepen their extinction. Previous experiments (Kearns and Weiss, 2005; Hendry, 1982; Reberg, 1982) showed that compounding (i.e., simultaneously presenting) extinguished cues can produce a reappearance of responding, suggesting that this is an effective means of temporarily restoring expectation. In a series of experiments involving food or shock cues, Rescorla showed that compounding previously-extinguished cues during further extinction deepened the extinction of those cues. Deepened extinction of food cues through their compound presentation has recently been replicated in a study by Janak and Corbit (2010).

The goal of the present study was to determine whether Rescorla's procedure could be used to deepen the extinction of cocaine cues. Kearns and Weiss (2012) have very recently shown that compounding extinguished cocaine cues produces a reappearance of cocaine seeking. This suggests that stimulus compounding could be used to temporarily restore expectation for cocaine during the further extinction of cocaine cues. Experiment 1 was a systematic replication of Rescorla's (2006) Experiment 3, but with discriminative stimuli (SDs) for cocaine rather than food reinforcement. Experiment 2 investigated whether a stronger deepened extinction effect would be produced by increasing the amount of compound extinction training.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Subjects

Naïve adult male Long-Evans rats served as subjects. Eight rats completed Experiment 1 and 10 rats completed Experiment 2. Rats were individually housed in plastic cages with wood chip bedding and metal wire tops. They were maintained at 85% of their free-feeding weights (approximately 350-450 g). The colony room where the rats were housed had a 12-h light:dark cycle with lights on at 08:00 h. Training sessions were conducted 5-7 days per week during the light phase of the light:dark cycle. Throughout both experiments, rats were treated in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy of Sciences, 1996) and all procedures were approved by American University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

2.2. Apparatus

Training took place in six operant chambers. Each chamber was 20 cm high, 23 cm long, and 18 cm wide and had aluminum front and rear walls, white translucent plastic side walls, a clear plexiglass ceiling, and a grid floor. A response lever and food trough were located on the front wall of the chamber. A click stimulus (approximately 15 clicks/s and 75dB), created by a BRS CL-201 click generator and amplified by a BRS AA-201 amplifier, was presented through a 20-cm diameter speaker located in an enclosure mounted approximately 21 cm above the chamber. A tone stimulus (approximately 4500 Hz and 75 dB) was delivered by a model SC628HR Sonalert (Mallory Sonalerts, Indianapolis, IN) that was mounted to the side of the enclosure that housed the click speaker. A light stimulus was provided by two 15-cm, 25-W, 120-VAC tubular light bulbs located 10 cm outside each of the side walls of the chamber. These light bulbs were operated at 103 VAC. Each chamber was housed inside a sound attenuation chest (Weiss, 1970) that had a continuously operating ventilation fan. A shielded houselight provided a low level of continuous illumination during all sessions. Experimental procedures were controlled by Med-Associates software (Med-PC, St. Albans, VT) running on a PC located in an adjacent room.

Cocaine (provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse) in a saline solution at a concentration of 2.56 mg/ml was infused at a rate of 3.19 ml/min by 10-ml syringes driven by Harvard Apparatus (South Natick, MA) or Med-Associates (St. Albans, VT) syringe pumps located outside of the sound attenuation chests. Tygon tubing extended from the 10-ml syringes to a 22-gauge rodent single-channel fluid swivel and tether apparatus (Alice King Chatham Medical Arts, Hawthorne, CA) that descended through the ceiling of the chamber. Cocaine was delivered to the subject through Tygon tubing that passed through the metal spring of the tether apparatus. This metal spring was attached to a plastic screw cemented to the rat's head to reduce tension on the catheter.

2.3. Procedure

Rats in Experiments 1 and 2 were trained on the same procedures except that there was only one session during Extinction Phase 2 in Experiment 1 while there were three sessions during Extinction Phase 2 in Experiment 2.

2.3.1. Lever-press acquisition

To facilitate later lever pressing for cocaine, rats were first trained for 2-3 sessions (~60 min each) to lever press for food pellets. Food pellets were available for lever pressing on a fixed-ratio 1 (FR-1) schedule and were also presented non-contingently every 120 s on average (range: 90-150 s) if a lever press was not made.

2.3.2. Surgery

Rats were then surgically prepared with chronic indwelling jugular vein catheters, using a modification of the procedure originally developed by Weeks (1962). In brief, under ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) anesthesia, approximately 3 cm of Silastic tubing (0.044mm i.d., 0.814mm o.d.) was inserted into the right jugular vein. This Silastic tubing was connected to 8 cm of vinyl tubing (Dural Plastics; 0.5mm i.d., 1.0mm o.d.) that was passed under the skin around the shoulder and exited the back at the level of the shoulder blades. The vinyl tubing was threaded through a section of Tygon tubing (10 mm long, 4 mm diameter) that served as a subcutaneous anchor. Six stainless steel jeweler's screws were implanted in the skull, to which a 20-mm plastic screw was cemented with dental acrylic. Catheters were flushed daily with 0.1 ml of a saline solution containing 1.25 U/ml heparin and 0.08 mg/ml gentamycin.

2.3.3. Cocaine self-administration

After 5-7 days of recovery in the homecage, rats were trained to self-administer cocaine on a 4-component multiple schedule. During tone, click, or light SD components lasting 180 s on average (range: 150-210 s), 0.5 mg/kg cocaine infusions were available for lever pressing according to a variable-interval (VI) 15-s schedule. These SD components alternated with SΔ components lasting 60 s on average (range: 45-75 s) where all stimuli were absent and lever pressing did not result in cocaine. Each of the three types of SD component (tone, click, and light) were equally likely to follow an SΔ component, with the restriction that there were no more than two consecutive SD components of the same type. A 30-s response correction contingency operated during the final 30 s of each SΔ component. According to this contingency, a 30-sec SΔ-termination clock was reset to zero by a response. This contingency was designed to reduce response rates during SΔ components. Sessions lasted for 150 min. Rats were trained with the schedule parameters described above for a minimum of 3 sessions and until they self-administered at least 20 infusions in a single session.

Then, the VI schedule that operated during SD components was increased to VI 60 s. The length of SD components was decreased to a mean of 60 s (range: 45 to 75 s) and the mean programmed duration of SΔ components was increased to 120 s (range: 90 to 150 s). The length of the response-correction contingency was also increased to 60 s. This value was subsequently increased up to as high as 150 s for individual rats if they persisted in responding during SΔ components. The amplitude of the tone stimulus was adjusted on an individual subject basis so that response rates during the tone and the click (the stimuli that would be compared to each other during subsequent testing) were comparable. Rats were trained on this terminal baseline procedure until (1) response rates during tone, click, and light SD components were at least 3 times higher than in SΔ components, and (2) response rates in the tone and the click were within 20% of each other when averaged over 2 sessions.

2.3.4. Extinction Phase 1

Rats next received extinction of the tone, click, and light stimuli. Each stimulus was presented 8 times per session (as in Rescorla, 2006, Experiment 3). Each tone, click, or light component lasted 45 s and was separated by a 135-s period where all stimuli were off. Lever pressing did not produce cocaine at any time and the response correction contingency in SΔ was discontinued. Rats were trained on this procedure for a minimum of 3 sessions and until response rates in tone and in click components were both less than 1 response per minute.

2.3.5. Extinction Phase 2

Following the procedure of Rescorla (2006), the auditory stimuli were used to compare the effectiveness of the deepened extinction treatment with the standard extinction treatment. For half the rats in each experiment, the tone was compounded with the light during Extinction Phase 2, while the click was always presented individually. For the other half of the rats, the roles of the tone and the click were reversed. Using the notation of Rescorla, the auditory stimulus that was compounded with the light was designated Stimulus X and the auditory stimulus that was always presented alone was designated Stimulus Y. The light was designated Stimulus A.

An Extinction Phase 2 session began with half of a session like those in Extinction Phase 1. That is, Stimuli X, Y, and A were presented individually 4 times each. This was followed by 8 presentations each of the AX compound stimulus (the light and one of the auditory stimuli presented simultaneously) and Stimulus Y (presented individually). Presentations of AX components and Y components lasted 45 s each and were separated by all-stimuli-off periods lasting 135 s. The numbers of components of each type that were presented in each session were based on those of Rescorla (2006, Experiment 3). As before, lever pressing did not produce cocaine at any time.

2.3.6. Spontaneous Recovery Test

A spontaneous recovery test was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the extinction of Stimuli X and Y. Following the final Extinction Phase 2 session, rats were left in their homecages for one week. The test session was like an extinction session in that lever pressing did not produce cocaine at any time and 45-s stimulus components alternated with 135-s periods where all stimuli were off. Following the procedure of Rescorla, the test began with 4 presentations of Stimulus A (the light). This was followed by 16 presentations each of the tone (T) and the click (C) in the order T-C-T-C-C-T-C-T-T-C-C-T-C-T-T-C-C-T-C-T-T-C-T-C-C-T-T-C-T-C-C-T. Because the tone and the click were counterbalanced in their roles as Stimuli X and Y over subjects in each experiment, this meant that the order of presentation of Stimuli X and Y was also counterbalanced over subjects.

2.4 Data analysis

For all statistical tests, α = 0.05. Response rate was the primary measure of interest for all training phases and for the test. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and/or paired samples t-tests were used to compare response rates across stimulus conditions.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1

3.1.1. Self-administration

Rats had a mean of 19.1 (± 2.5 SEM) total self-administration sessions. Averaged over the last two sessions, mean (± SEM) response rates (responses/min) in Stimuli X, Y, A, and all-stimuli-off components were 3.6 (± 0.6), 3.7 (± 0.7), 5.0 (± 0.9), and 0.7 (± 0.2), respectively. A repeated measures ANOVA performed on X, Y, and A response rates revealed a significant effect of stimulus condition (F[2,14] = 9.5, p < 0.01). Responding to Stimulus A (the light) was significantly higher than responding to either X or Y (t[8]s ≥ 2.8, ps < .05), but, most importantly, X and Y did not differ from each other (t[8] = 1.0, p > 0.3).

3.1.2. Extinction Phase 1

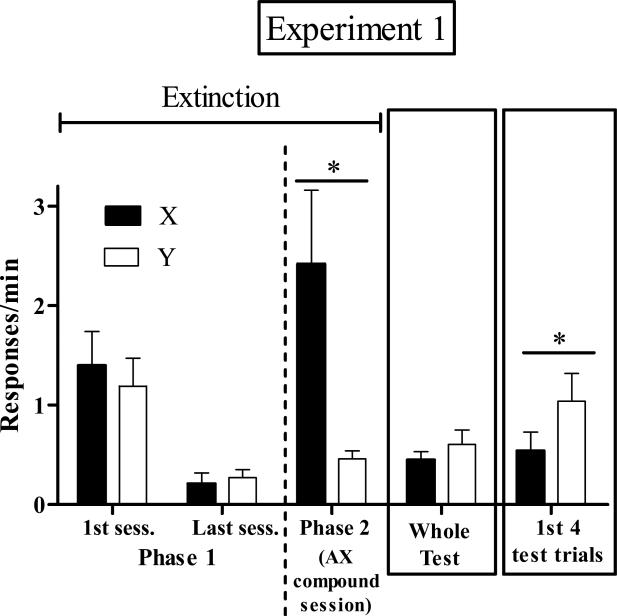

Six of 8 rats met the criterion of responding at less than 1 response per min in X and Y within 3 extinction sessions, while two rats required 1-2 extra sessions. The left-hand portion of Figure 1 presents mean (± SEM) response rates in X and Y during the first and final Extinction Phase 1 sessions. A 2-x-2 (Stimulus-x-Session) repeated measures ANOVA performed on these response rates confirmed that there was a significant effect of Session (F[1,7] = 20.8, p < 0.005), but there was no effect of Stimulus and no Stimulus-x-Session interaction (both Fs < 1). Mean responses per min during Stimulus A (not presented in Figure) over these sessions declined from 2.6 (± 0.8 SEM) to 0.8 (± 0.2 SEM). Mean response rates during all-stimuli-off periods were less than 0.5 responses per min during both sessions.

1.

Experiment 1 results. Data presented are the mean (±SEM) response rates (responses per min) in Stimuli X (black bars) and Y (white bars) during the first and final sessions of Extinction Phase 1, the Extinction Phase 2 session, the whole spontaneous recovery test, and only the first 4 X and Y presentations of the test. * indicates p < 0.05.

3.1.3. Extinction Phase 2

The center two bars of Figure 1 present mean (± SEM) response rates during the 8 presentations of the AX compound and during the final 8 presentations of stimulus Y during the Extinction Phase 2 session. Mean response rates were over 2.0 per min during AX, but less than 0.5 during Y. This difference was significant (t[8] = 2.6, p < 0.05). Mean response rate during all-stimuli-off periods were less than 0.2 responses per min.

3.1.4. Spontaneous Recovery Test

Mean (± SEM) response rates to X and Y during the spontaneous recovery test are presented in the right-hand portion of Figure 1. Response rates over the entire 16-block test (“Whole Test”) are presented first. (Rats made less than 0.3 responses per min during all-stimuli-off periods). Though the mean response rate to Y was slightly higher than that to X, this difference was not significant (t[8] = 1.3, p > 0.2). However, in comparing the spontaneous recovery test procedures of the current experiment and those of Rescorla's (2006) Experiment 3, a potentially important difference in the number of X and Y test presentations was noted. Sixteen presentations each of X and Y were used here, whereas Rescorla as well as Janak and Corbit (2010) used only 4 presentations each. Therefore, an additional analysis was performed using only the data from the first 4 presentations of X and Y during the test in the present experiment. These response rates are represented by the bars labeled “1st 4 test trials” in Figure 1. Now, there was significantly more responding to Y than to X (t[7] = 3.0, p < 0.05, Cohen's d = 0.75), just as was found in the previous studies using only 4 presentations each (Janak and Corbit, 2010; Rescorla, 2006).

3.2. Experiment 2

3.2.1. Self-administration

Rats had a mean of 29.4 (± 3.5 SEM) total self-administration sessions. Averaged over the last two sessions, mean (± SEM) response rates in Stimuli X, Y, A, and all-stimuli-off components were 4.7 (± 1.1), 4.8 (± 1.1), 6.1 (± 1.2), and 1.1 (± 0.2), respectively. Response rates again differed over SDs (F[2,18] = 16.0, p < 0.001), with responding to A significantly higher (t[9]s ≥ 3.9, ps < 0.005) than that to either X or Y, which did not differ from each other (t[9] = .2, p > 0.85).

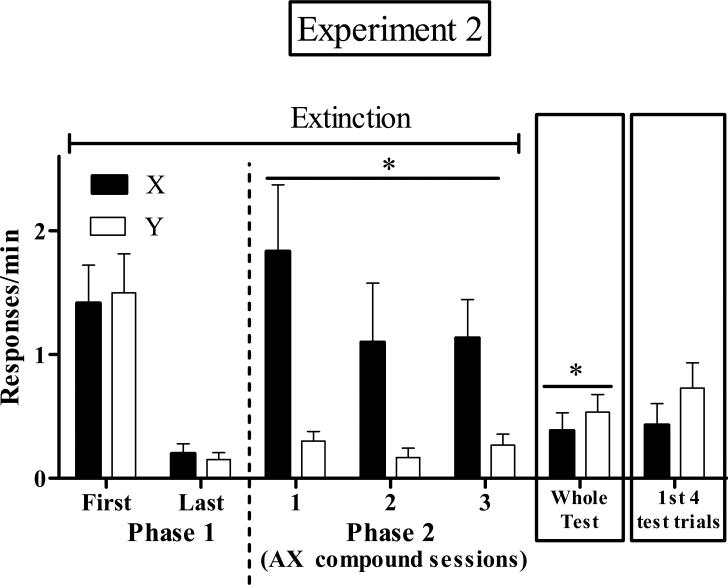

3.2.2. Extinction Phase 1

Two rats required 4 sessions (rather than 3) to meet the extinction criterion. As Figure 2 (middle portion) illustrates, responding in X and Y significantly declined from the first to last extinction session (F[1,9] = 20.3, p < 0.005), but X and Y response rates did not differ from each other (F < 1). Mean responses per min during Stimulus A (not presented in Figure) over these sessions declined from 2.7 (± 0.5 SEM) to 1.2 (± 0.4 SEM). Mean response rates during all-stimuli-off periods were less than 0.5 responses per min during both sessions.

2.

Experiment 2 results. Data presented are the mean (±SEM) response rates (responses per min) in Stimuli X (black bars) and Y (white bars) during the first and final sessions of Extinction Phase 1, the 3 sessions Extinction Phase 2, the whole spontaneous recovery test, and only the first 4 X and Y presentations of the test. * indicates p < 0.05. Note that the Y-axis range is smaller than in Figure 1.

3.2.3. Extinction Phase 2

Responding to the AX compound was significantly higher than to Y (F[1,9] = 7.7, p < 0.05), but there was no effect of Session (F[2,18] = 2.8, p < 0.09) or Stimulus-x-Session interaction (F[2,18] = 2.1, p > 0.15). Mean response rates during all-stimuli-off periods were less than 0.2 responses per min throughout this phase.

3.2.4. Spontaneous Recovery Test

Responding to Y was significantly greater than to X (t[9] = 3.0, p < 0.05, Cohen's d = 0.33) over the whole test, but not during the first 4 test presentations (t[9] = 1.3, p > 0.2). Mean responses per min during all-stimuli-off periods was less than 0.3.

3.3. Combined Analysis

An additional, post-hoc analysis that pooled the subjects from Experiments 1 and 2 was performed that included Experiment as a between-subjects variable. Though Experiment 2 was run slightly later than Experiment 1, rats in both experiments were trained on the same procedures, with the same dose of cocaine, and to the same behavioral criteria. A set of ANOVAs like those performed above indicated that there was no significant effect of Experiment or interactions involving this variable at any stage of training or on the test (all Fs < 1). Now, however, test responding to Y was significantly higher than to X for both the first 4 components measure and for the whole-test measure (F[1,16]s > 6.1, ps < 0.05, Cohen's d = 0.38 for whole-test measure, Cohen's d = 0.63 for first 4 test presentations measure).

4. Discussion

The present study provides evidence that the extinction of cocaine cues could be deepened by compounding already-extinguished cocaine cues during additional extinction training. This systematically replicates the finding of previous studies showing that compound cue presentation during extinction deepened the extinction of non-drug cues (Janak and Corbit, 2010; Rescorla, 2006). These results provide additional support for the hypothesis of error-correction learning models (e.g., Rescorla-Wagner) that extinction learning is the product of the discrepancy between expectation and outcome. The present experiment and previous studies (Janak and Corbit, 2010; Rescorla, 2000, 2006) have shown that increasing expectation for the reinforcer during extinction by simultaneously presenting multiple excitatory cues results in enhanced extinction learning. Conversely, Rescorla (2003) has shown that decreasing expectation for the reinforcer during extinction by presenting a conditioned inhibitor (a signal for the absence of the reinforcer) results in less extinction learning. Taken together, these results indicate that error-correction plays an important role in extinction learning.

Overall, it appeared that there was little, if any, benefit to giving more than a single compound cue extinction session in the present study. The mean difference between spontaneous recovery to X and to Y was similar over Experiment 1, where there was only one compound cue extinction session, and Experiment 2, where there were 3 such sessions. The formation of within-compound associations between X and A during extended compound cue extinction training could potentially explain why there was no added benefit of the extra sessions. Basic learning research has shown that when two stimuli are presented in compound, associations may form between the two elements and when one of the elements is subsequently presented alone, a representation of the other element is activated (Cunningham, 1981; Rescorla, 1982; Williams et al., 1986). In the present procedure, presentations of stimulus X alone during the test for spontaneous recovery may have activated the representation of stimulus A, if within-compound associations had been learned. This would be expected to result in more responding to X than if an A-X within-compound association had not been learned. Because there were 24 presentations of the AX compound in Experiment 2 as compared to only 8 AX presentations in Experiment 1, rats in Experiment 2 would have had more opportunity to learn the within-compound association than rats in Experiment 1. Such learning may have offset the benefit of any additional deepened extinction produced by the extra compound cue extinction training. Future research is needed to determine how to best mitigate the potential influence of within-compound associations on the stimulus-compounding-induced deepened extinction effect.

During self-administration training and extinction, the light (Stimulus A) consistently controlled more lever pressing than the two auditory stimuli. This unplanned result should not alter the main conclusion of the present study because the auditory stimuli were the cues compared in testing. The light was used only as the extra excitor that was compounded with one of the auditory cues. A similar situation occurred in one of the deepened extinction experiments in the original study by Rescorla (2006, Experiment 1). It might be anticipated that a relatively strong Stimulus A would result in a greater deepened extinction effect because compounding such a cue with Stimulus X should produce greater expectation for cocaine than would a weaker Stimulus A. However, this benefit would be offset if a more salient Stimulus A competed with the weaker Stimulus X for the associative changes resulting from repeated non-reinforced presentations of the AX compound (Rescorla, 2006).

In the present experiments, the test for spontaneous recovery included 16 presentations of Stimuli X and Y, while the previous experiments investigating deepened extinction with non-drug cues used only 4 presentations of each stimulus (Janak and Corbit, 2010; Rescorla, 2006). A longer test was used here in an effort to potentially capture more responding during the spontaneous recovery test. However, a relatively small effect (Cohen's d = 0.33-0.38) of deepened extinction training was found on the longer test. But when responding over only the first 4 test presentations was examined, a larger effect (Cohen's d = 0.63-0.75) that is more similar to that observed in the earlier studies with non-drug cues that used only 4 test presentations was found.

Though the effect found in the present study may have been modest, it is worth noting that it was achieved through a manipulation as simple and non-invasive as presenting cues simultaneously rather than individually. Further increasing the expectation for cocaine during the extinction of cocaine cues might be expected to lead to a greater deepening effect. In the procedure used here, X was compounded with Stimulus A which had already been subjected to extinction on its own for multiple sessions. A greater effect might have been observed if the additional extinction of X occurred against a more excitatory background than that provided by Stimulus A. Support for this hypothesis comes from a study showing that the strength of a cocaine-based conditioned inhibitor depended on the amount of cocaine-based excitation present when that inhibitor was created (Kearns et al., 2005). Increasing the amount of excitation present during extinction could be accomplished by, for example, presenting 3 or more cocaine cues simultaneously, or perhaps by conducting extinction of cocaine cues in multiple different contexts in which cocaine taking had previously occurred. The results of studies (like the present one) investigating methods of more effectively extinguishing drug cues could contribute to the development of more effective drug abuse treatments.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This research was supported by Award Number R01DA008651 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. NIDA did not play a role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the design of the experiment. David Kearns and Brendan Tunstall performed the experiment. David Kearns analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bouton ME. Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biol. Psych. 2002;52:976–986. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, Mozley PD, McElgin W, Fitzgerald J, Reivich M, O'Brien CP. Limbic activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. Am. J. Psych. 1999;156:11–18. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Tiffany ST. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction. 2002;97:155–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL. Associations between the elements of a bivalent compound stimulus. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Proc. 1981;7:425–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DS, Tiffany ST, Glautier S, Remington B. Addictive Behaviour: Cue Exposure Theory and Practice. Wiley and Sons; West Sussex, England: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Grusser S, Wrase J, Klein S, Hermann D, Smolka MN, Ruf M, Weber-Fahr W, Flor H, Mann K, Braus DF, Heinz A. Cue-induced activation of the striatum and medial prefrontal cortex is associated with subsequent relapse in abstinent alcoholics. Psychopharmacology. 2004;175:296–302. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havermans RC, Jansen ATM. Increasing the efficacy of cue exposure treatment in preventing relapse of addictive behavior. Addict. Behav. 2003;28:989–994. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry JS. Summation of undetected excitation following extinction of the CER. Anim. Learn. Behav. 1982;10:476–482. [Google Scholar]

- Janak PH, Corbit LH. Deepened extinction following compound stimulus presentation: noradrenergic modulation. Learn. Mem. 2010;18:1–10. doi: 10.1101/lm.1923211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamin LJ. Predictability, surprise, attention, and conditioning. In: Campbell BA, Church RM, editors. Punishment and Aversive Behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York: 1969. pp. 276–296. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DN, Weiss SJ. Reinstatement of a food-maintained operant response by compounding discriminative stimuli. Behav. Proc. 2005;70:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DN, Weiss SJ. Extinguished cocaine cues increase drug seeking when presented simultaneously with a non-extinguished cocaine cue. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;121:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DN, Weiss SJ, Schindler CW, Panlilio LV. Conditioned inhibition of cocaine seeking in rats. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Proc. 2005;31:247–253. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.31.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Scanley BE, Tucker KA, Oliveto A, Prince C, Sinha R, Potenza MN, Skudlarski P, Wexler BE. Cue-induced brain activity changes and relapse in cocaine-dependent subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:644–650. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber S, Croissant B, Heinz A, Mann K, Flor H. Cue exposure in the treatment of alcohol dependence: effects on drinking outcome, craving and self-efficacy. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007;45:515–529. doi: 10.1348/014466505X82586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh NJ. A theory of attention: variations in the associability of stimuli with reinforcement. Psychol. Rev. 1975;82:276–298. [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Sciences . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce JM, Hall G. A model of Pavlovian learning: variations in the effectiveness of conditioned but not of unconditioned stimuli. Psychol. Rev. 1980;87:532–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reberg D. Compound tests for excitation in early acquisition and after prolonged extinction of conditioned suppression. Learn. Motiv. 1972;3:246–258. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Some consequences of associations between the excitor and the inhibitor in a conditioned inhibition paradigm. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Proc. 1982;8:288–298. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Extinction can be enhanced by a concurrent excitor. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Proc. 2000;26:251–260. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.26.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Protection from extinction. Learn. Behav. 2003;31:124–132. doi: 10.3758/bf03195975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Deepened extinction from compound stimulus presentation. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Proc. 2006;32:135–144. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.32.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA, Wagner AR. A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. In: Black AH, Prokasy WF, editors. Classical Conditioning II: Current Research and Theory. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York: 1972. pp. 64–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Rubonis AV, Gulliver SB, Colby SM, Binkoff JA, Abrams DB. Cue exposure with coping skills training and communication skills training for alcohol dependence: 6- and 12-month outcomes. Addiction. 2001;96:1161–1174. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96811619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton RS, Barto AG. Toward a modern theory of adaptive networks: expectation and prediction. Psychol. Rev. 1981;88:135–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Li C-SR. Imaging stress- and cue-induced drug and alcohol craving: association with relapse and clinical implications. Drug Alc. Rev. 2007;26:25–31. doi: 10.1080/09595230601036960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Childress AR, Jayne M, Ma Y, Wong C. Cocaine cues and dopamine in dorsal striatum: mechanism of craving in cocaine addiction. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:6583–6588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1544-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Childress AR, Jayne M, Ma Y, Wong C. Dopamine increases in striatum do not elicit craving in cocaine abusers unless they are coupled with cocaine cues. Neuroimage. 2008;39:1266–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AR, Rescorla RA. Inhibition in Pavlovian conditioning: application of a theory. In: Boakes RA, Halliday MS, editors. Inhibition and Learning. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1972. pp. 301–336. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks JR. Experimental morphine addiction: method for automatic intravenous injections in unrestrained rats. Science. 1962;138:143–144. doi: 10.1126/science.138.3537.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SJ. An effective and economical sound attenuation chamber. Exp. Anal. Behav. 1970;13:37–39. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1970.13-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DA, Travis GM, Overmier BJ. Within-compound associations modulate the relative effectiveness of differential and Pavlovian conditioned inhibition procedures. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Proc. 1986;12:351–362. [Google Scholar]