Abstract

Objective:

To examine the effect of nighttime sleep duration on mortality and the effect modification of daytime napping on the relationship between nighttime sleep duration and mortality in older persons.

Design:

Prospective survey with 20-yr mortality follow-up.

Setting:

The Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Aging Study, a multidimensional assessment of a stratified random sample of the older Jewish population in Israel conducted between 1989-1992.

Participants:

There were 1,166 self-respondent, community-dwelling participants age 75-94 yr (mean, 83.40, standard deviation, 5.30).

Measurements:

Nighttime sleep duration, napping, functioning (activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, Orientation Memory Concentration Test), health, and mortality.

Results:

Duration of nighttime sleep of more than 9 hr was significantly related to increased mortality in comparison with sleeping 7-9 hr (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.31, P < 0.01) after adjusting for demographic, health, and function variables, whereas for short nighttime sleep of fewer than 7 hr mortality did not differ from that of 7-9 hr of sleep. For those who nap, sleeping more than 9 hr per night significantly increased mortality risk (HR = 1.385, P < 0.05) and shorter nighttime sleep reduced mortality significantly in the unadjusted model (HR = 0.71, P < 0.001) but only approached significance in the fully adjusted model (HR = 0.82, P = 0.054). For those who do not or sometimes nap, a short amount of sleep appears to be harmful up to age 84 yr and may be protective thereafter (HR = 1.51, confidence interval [CI] = 1.13-2.02, P < 0.01; HR = 0.76, CI = 0.49-1.17, in the fully adjusted model, respectively).

Conclusions:

The findings are novel in demonstrating the protective effect of short nighttime sleep duration in individuals who take daily naps and suggest that the examination of the effect of sleep needs to take into account sleep duration per 24 hr, rather than daytime napping or nighttime sleep per se.

Citation:

Cohen-Mansfield J; Perach R. Sleep duration, nap habits, and mortality in older persons. SLEEP 2012;35(7):1003–1009.

Keywords: Sleep, mortality, old age

INTRODUCTION

Sleep is an important component of a healthy lifestyle. Both short and long duration of sleep have been associated with increased mortality.1– Pooled analyses conducted in a recent review of 16 studies of persons whose mean age ranged from 41 to 77 yr indicated that sleeping fewer than 7 hr per night increased mortality risk by 12%, and sleeping more than 8-9 hr per night increased mortality risk by 30% compared with those sleeping 7-8 hr per night.1 Increases in the duration of sleep in older persons has been reported,4,5 highlighting the importance of understanding the link between sleep duration and mortality in these individuals.

Greater prevalence of napping in older adults than younger adults has also been reported.6,7 Several studies have reported an association between napping and increased mortality in older persons,8–11 although no such relationship was found in a study of older Taiwanese persons.12

Literature regarding the relationship between nighttime sleep duration and nap habits and mortality in older persons is scant.11,12 The goal of the current study is to investigate this relationship in a cohort of older persons in Israel for which a 20-yr mortality follow-up study was available.

The specific question is: what is the effect of nighttime sleep duration on mortality, and what is the effect modification of daytime napping on the relationship between nighttime sleep duration and mortality?

We hypothesize that mortality is increased for those with nighttime sleep of more than 9 hr per night,1,12 and for those who sleep 7 hr or fewer per night.13 We also examined the relationship between nighttime sleep duration, napping, and mortality.

METHODS

Participants and Procedure

The sample included participants from the Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Aging Study (CALAS).14–17 The CALAS is a multidimensional survey of a random sample of the older Jewish population in Israel, stratified by age group in yr (75-79, 80-84, 85-89, 90-94), sex, and place of birth (Asia-Africa, Europe-America, Israel). Data collection took place during 1989-1992. The inclusion criteria were that participants had to be self- respondent, community-dwelling residents age 75-94 yr. Although data on some institutionalized persons are available, they were excluded from this analysis because of the potential effects of the institutional procedures on sleep. Interviews were conducted by trained research assistants at participants' homes. The CALAS was approved for ethical treatment of human participants by the Institutional Review Board of the Chaim Sheba Medical Center in Israel. Of the 1,200 community dwelling participants, 34 (2.8%) did not have information on nighttime sleep. These participants were significantly older, with fewer income resources, with lower subjective health and more activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and cognitive difficulties, compared with the 1,166 participants who provided information on nighttime sleep. The current analyses include 1,166 self-respondent participants age 75-94 yr for whom length of nighttime sleep was available. Of 1,063 participants who responded to the item “Are you currently working for pay?”, 929 replied “no” and 134 replied “yes”. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of retirement was 72.98 yr (16.10), for the 906 respondents to this question. Because of these numbers, employment status was not included in the analysis. The demographic description of the sample is presented in Table 1.

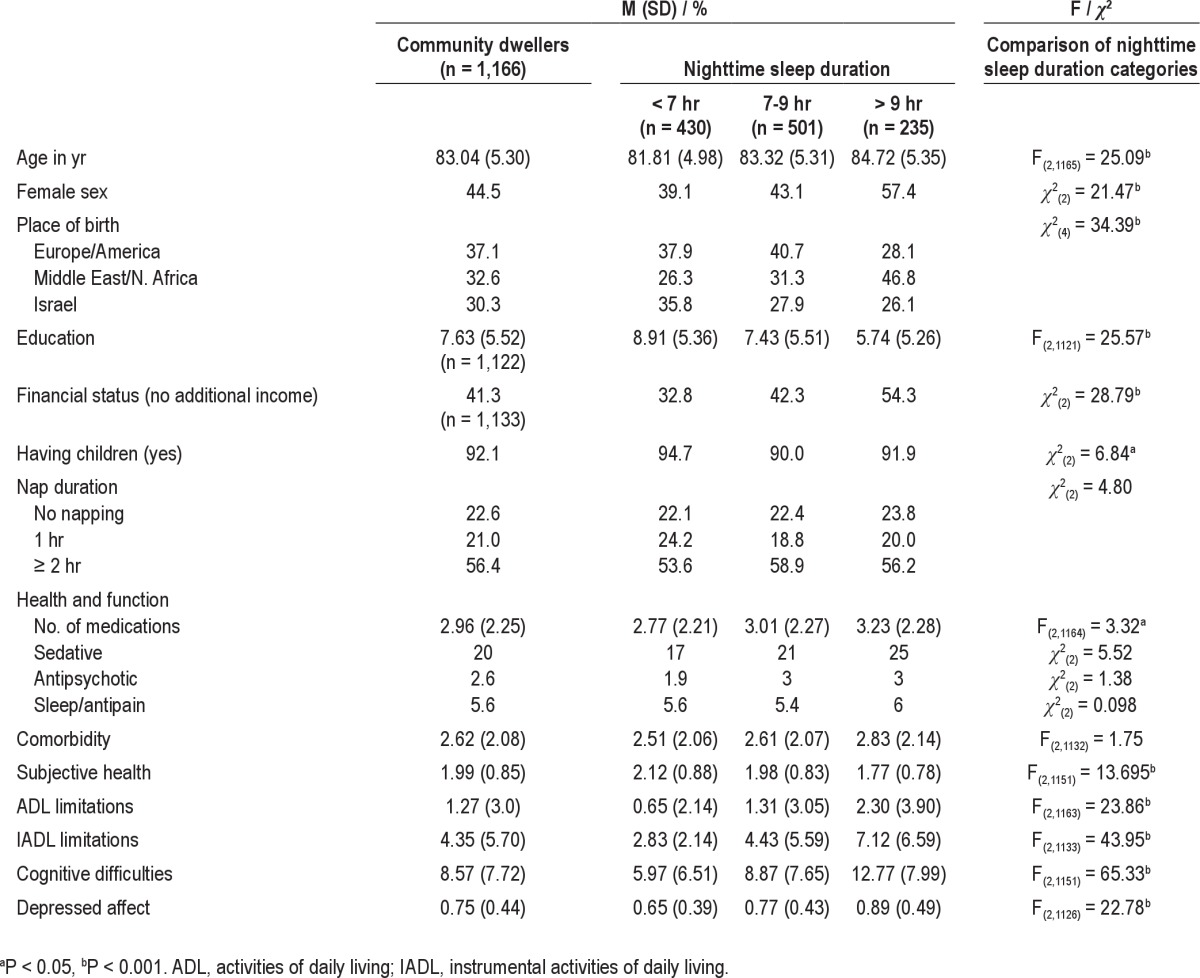

Table 1.

Characteristics of the full sample and by categories of nighttime sleep duration

Measures

Background

Sociodemographic factors included sex, age, place of birth (Israel, Middle East/North Africa, or Europe/America), marital status, number of children, education (number of years of education), and financial status (whether the participant had income additional to the basic National Insurance pension).

Sleep variables

Nighttime sleep duration was measured by calculating the difference between the time to bed at night and time to rise in the morning. The corresponding items were: “At what time do you usually go to sleep at night?”, and “At what time do you usually get up in the morning”, respectively. Napping was measured by the item, “do you sleep during the day?” (yes, no, sometimes).

Function

ADL18 was assessed by asking respondents to rate their difficulty in performing 7 different vital activities (crossing a small room, washing, dressing, eating, grooming, transferring, and toileting) on a scale from “no difficulty” (0) to “complete disability” (3). The sum score ranged from 0 to 21. Cronbach alpha coefficient of this measure was 0.88. IADL19 is a scale that consists of 7 items, each rating the difficulty of performing different activities (preparing meals, daily shopping, shopping for clothes, doing light housekeeping, doing heavy housework, taking the bus, and doing laundry) on a scale similar to that used for ADL (range, 0-21). Alpha coefficient of this measure was 0.87. Cognitive difficulties were measured by the Orientation-Memory-Concentration (OMC) Test.20 Seven items tested basic cognitive functions such as knowing the current date and time, remembering a name and an address, and counting backward. Errors were multiplied by prefixed weights and added (range, 0-28). Alpha coefficient was 0.73. A high score on each of the function measures (ADL, IADL, OMC Test) indicates greater difficulties in function.

Health

Health measures included subjective health (terrible, okay, good, or excellent); number of medications as inspected and counted by the interviewer (range 0–8); comorbidity was assessed by the number of diseases for which the participant had been diagnosed from a list of 18 chronic diseases (such as diabetes and cancer; range, 0-18). Depressed affect was measured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD).21 Respondents rated the frequency of experiencing 20 depressive symptoms in the past month on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day). The items expressed negative affect, lack of well-being, psychosomatic reactions, and interpersonal distress. The score was the respondents' mean rating after reversing 4 positive items (range, 0-3). Alpha coefficient was 0.88. Item 10 was removed from the analysis and was treated as a separate variable that measures loneliness.

Mortality follow-up

Mortality data within 20 yr from the date of sampling were recorded from the Israeli National Population Register. Of the original sample, 58 participants were still alive and therefore were censored. Hence we have complete all-cause mortality data on 95.2% of the sample.

Statistical Analysis

The effect of sleep on 20-yr mortality was tested using Cox regression models. Three models examining the effect of sleep on mortality were analyzed: the first unadjusted, the second adjusted for stratification variables (age, sex, country of origin), as well as for education, financial status, and having children, and the third adjusted for demographics, health, and function variables. These models were conducted twice, first for the entire population and then separately for those who nap during the day and those who sometimes or do not nap. That is, stratification by napping was performed to assess the potential effect modification of napping. The latter analysis was examined for effects on sex and subsequently, for age. Finally, the interaction effect of nighttime sleep duration by daytime napping as a mortality predictor was examined.

RESULTS

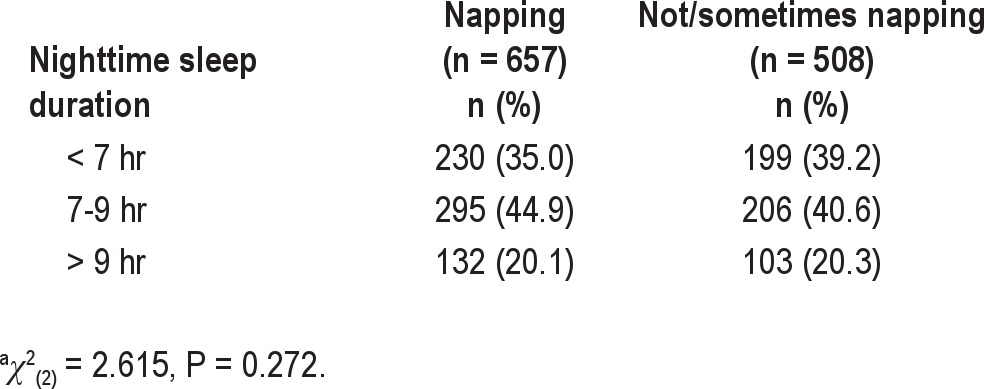

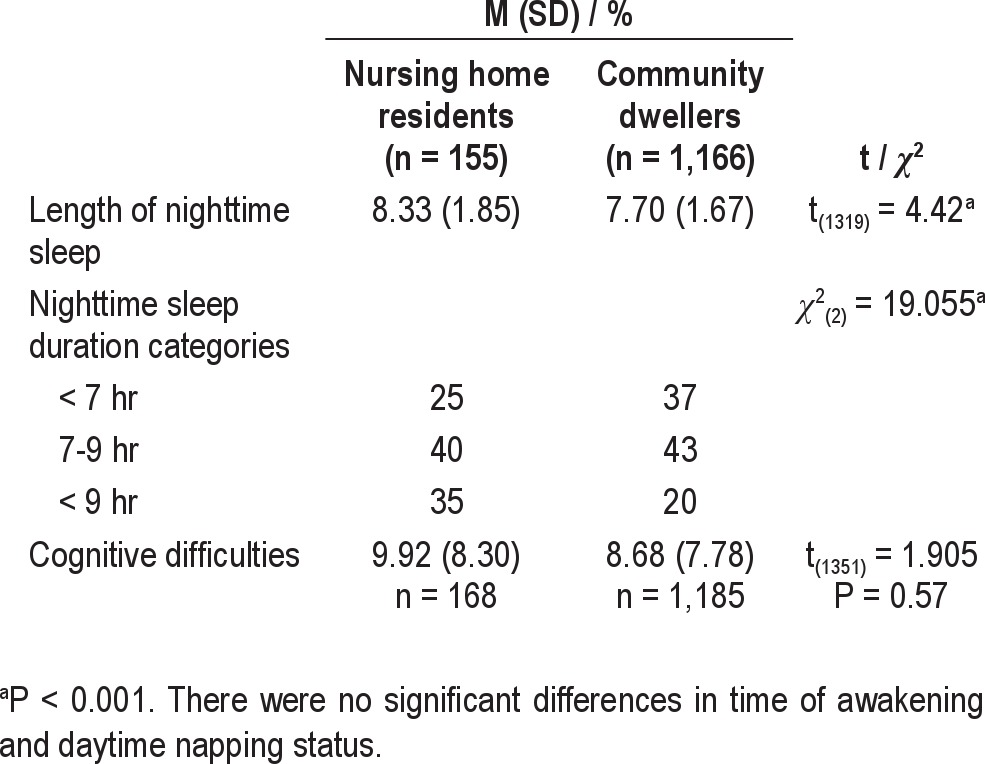

Descriptive information on background variables and sleep variables is presented in Table 1. Napping and nighttime sleep duration were found to be independent constructs (χ2(2) = 2.615, P = 0.272; Table 2). Baseline differences between nursing home residents and community dwelling participants are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

The relationship between daytime napping and nighttime sleep durationa

Table 3.

Baseline differences between nursing home residents and community dwelling participants

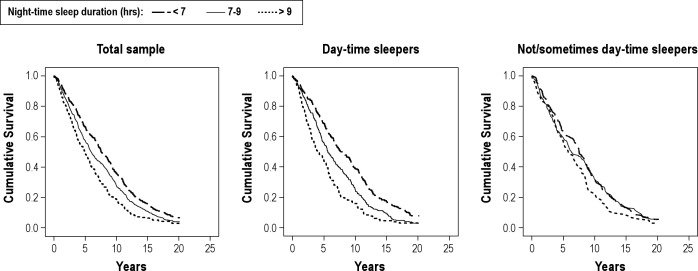

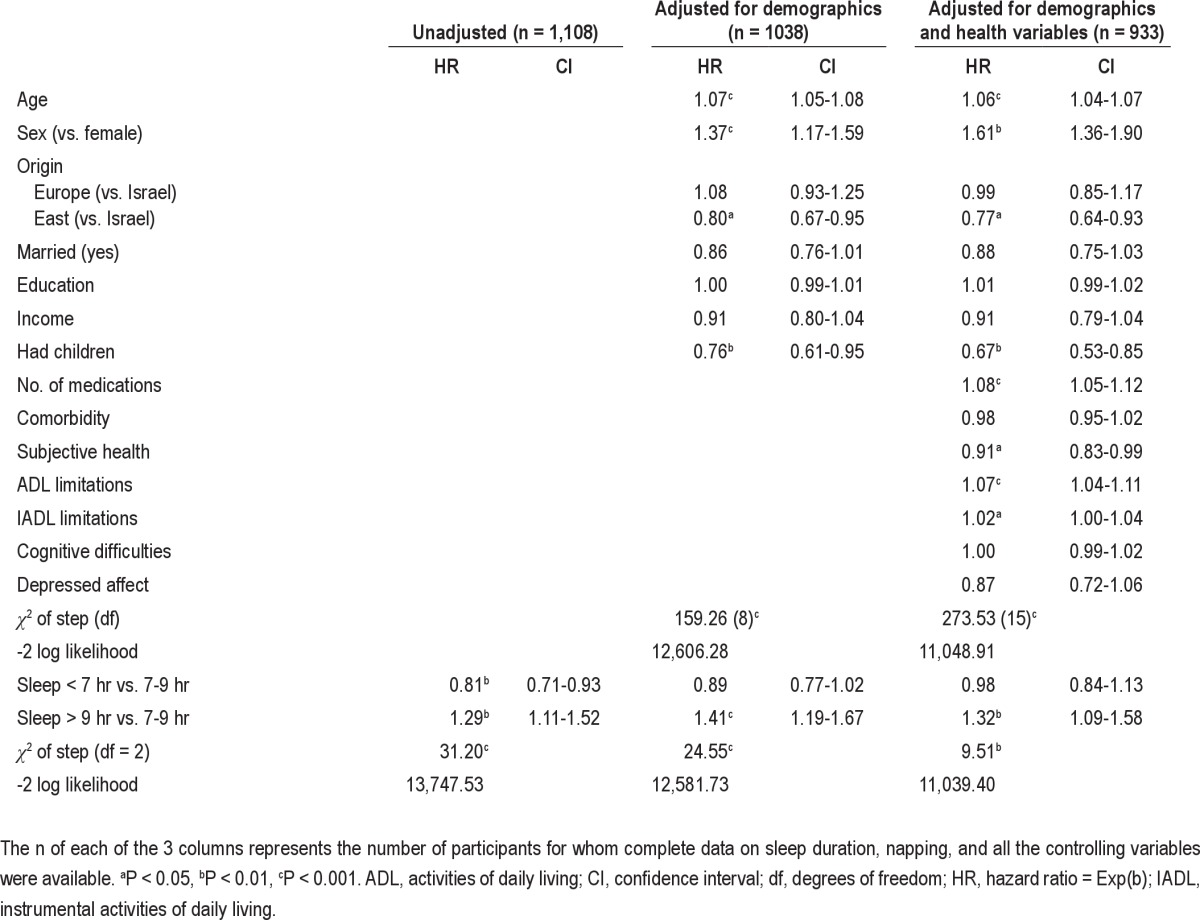

Duration of nighttime sleep of more than 9 hr was significantly related to increased mortality at 20-year follow-up in comparison with 7-9 hr after controlling for demographic, health, and function variables (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.31, P < 0.01, Table 4). In contrast, sleeping fewer than 7 hr was significantly associated with decreased mortality in comparison with 7-9 hr of sleep in the unadjusted model (HR = 0.81, P < 0.01; Table 4 and Figure 1), but not in the fully adjusted model (Table 4). The 20-yr mortality findings by napping status are presented in Table 5. Findings of the unadjusted model are presented in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Cox regression predicting mortality in 20 yr from date of first interview by nighttime sleep duration (n = 1,166)

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to nighttime sleep duration in the total sample (n = 1,166), those who sleep during the day (n = 657), and those who does not or sometimes sleep during the day (n = 508).

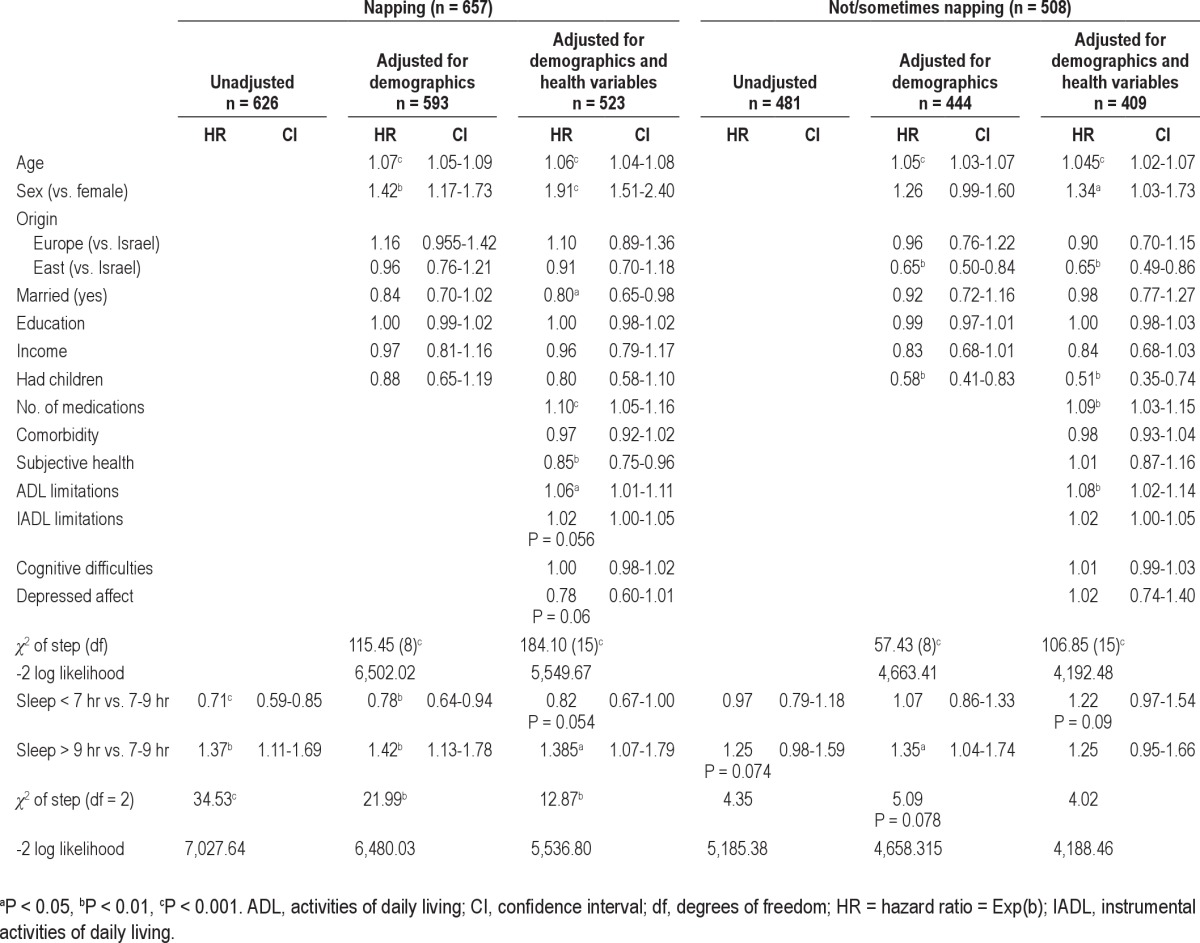

Table 5.

Cox regression predicting mortality in 20 yr from date of first interview by nighttime sleep duration, and napping status (n = 1166)

No direct association was found between napping status and mortality (results available from authors). However, for those who nap during the day, sleeping more than 9 hr per night compared with 7-9 hr per night significantly increased mortality risk in the fully adjusted model (HR = 1.385, P < 0.05). For those who nap, sleeping fewer than 7 hr per night compared with 7-9 hr significantly reduced mortality in the unadjusted model (HR = 0.71, P < 0.001; Figure 1) and after adjusting for demographics (HR = 0.78, P < 0.01) but only approached significance in the fully adjusted model (HR = 0.82, P = 0.054). This is probably due to the smaller sample size. In contrast, for those who did not nap during the day, the unadjusted model suggests a convergence of all types of length in terms of mortality (Figure 1), whereas the adjusted model raised the possibility that both a shorter and a longer duration of nighttime sleep may be associated with somewhat higher mortality, though this finding was not significant, probably because of the insufficient sample size.

The interaction effect of nighttime sleep duration and daytime napping as a mortality predictor was significant in the unadjusted model (HR = 1.03, P < 0.01; χ2(1) = 16.925, P < 0.001) and after adjusting for demographics (HR = 1.02, P < 0.01; χ2(1) = 10.72, P < 0.01), but was not significant in the fully adjusted model.

The relationships between napping status, nighttime sleep, and mortality were unaffected by sex (results available from authors). As for age, we found that for those who do not or sometimes nap, a short amount of sleep appears to be harmful in individuals up to age 84 yr and may be protective thereafter (HR = 1.51, CI = 1.13-2.02, P < 0.01; HR = 0.76, CI = 0.49-1.17, in the fully adjusted model, respectively). Although this suggests a potential change in trend based on age for those who do not nap, the sample sizes are too small to establish this trend. For those who do nap, in the fully adjusted model, shorter nighttime sleep seemed to be consistently protective, for those age 75-84 yr (HR = 0.81, CI = 0.63-1.04, P = 0.099) as for those age 85-94 yr (HR = 0.86, CI = 0.60-1.04). Again, sample sizes were too small to establish significant relationship.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the relationship among nighttime sleep, nap habits, and mortality in a random sample of older Israelis, with all participants having survived to at least 75 yr old at baseline. The hypothesis concerning long nighttime sleep was confirmed, i.e., for the total sample, we found that compared with nighttime sleep of 7-9 hr, sleeping more than 9 hr per night was associated with significantly increased mortality, after adjusting for demographic, health, and function variables. The hypothesis concerning short nighttime sleep was not confirmed, i.e., for nighttime sleep of fewer than 7 hr mortality did not differ from that of 7-9 hr of sleep. The effect of short nighttime sleep duration seems to be modified by daytime napping status. For those who nap during the day, in the fully adjusted model, mortality increased significantly for long nighttime sleepers whereas short nighttime sleep seemed to have a protective effect on mortality at a level approaching significance (P = 0.054), probably due to a small sample size. Supporting the effect of daytime napping status on mortality, the interaction effect of nighttime sleep duration and daytime napping was significant in the unadjusted model and after adjusting for demographics. However, it did not reach significance in the fully adjusted model. For those who did not or sometimes nap, we found a trend for increased mortality for both a shorter and a longer duration of nighttime sleep, though neither was significant due to the insufficient sample size.

Our finding of increased mortality for long nighttime sleepers has been commonly reported in middle-age and old-age populations,1–3,12,22 with a stronger association found in older cohorts than younger ones.1 Several mechanisms of the relationship between long sleep and mortality have been proposed,23 including sleep fragmentation, fatigue, depression, and decreased exercise. In older populations, the association between long nighttime sleep duration and mortality may represent an end-of-life process such as frailty, boredom, inactivity, or dementia.

We found that short nighttime sleep may have either no effect on mortality (full sample results) or a protective effect on mortality (for those who nap), which stands in contrast to most research suggesting that short nighttime sleep has a negative effect on mortality.13 Specifically, previous investigations associated short nighttime sleep with increased mortality in middle-aged participants3,24–26 and less commonly in older persons.27 Three studies have reported no such association in older persons.12,22,28 Current findings go beyond those previous reports in that we found that for those who nap during the day, a short nighttime sleep duration may be protective in terms of mortality. In line with that finding, the mortality-related benefits of siesta have been documented in younger populations. Specifically, siesta was inversely associated with coronary mortality in Greek adults age 20-86 yr, particularly for working men.29 However, in disagreement with current findings, previous studies of persons in middle and old age have reported associations between siesta and excess mortality risk in Israel,9,30,31 and negative effects of siesta in populations traditionally associated with siesta-taking including in Greece32 and in Central America33 have been reported. The combined effect of napping and short nighttime sleep duration has been scantly examined. In contrast with current results, findings so far indicate either a lack of combined effect on mortality12 or a hazardous effect.11 Specifically, when considering different nighttime sleep durations together with different daytime nap durations, no significant effect for napping on mortality was found in a sample of Taiwanese community residents age 64 yr and older.12 In another study,11 nighttime sleep of less than 6 hr increased mortality risk compared with nighttime sleep of 6-8 hr in US women age 69 yr and older who reported daily napping. Discrepancies with the latter findings may be due to a younger age range than in the current study and studying women only. Given the fragmented nature of sleep in older persons,34 a nap augmenting short nighttime sleep duration can be construed as providing an additional avenue for sleep and is thus beneficial in enabling a longer 24-hr sleep duration. Indeed, a significantly longer 24-hr sleep duration was reported in older women who nap compared with those who did not nap daily.11 The reasons for this pattern of sleep being more beneficial than normal length of sleep are yet unclear and warrant future research. Alternatively, it is possible that reporting short nighttime sleep duration could indicate getting up for an activity, which in itself indicates a certain vitality. Thus, we cannot differentiate whether this pattern reflects healthy activity, causes it, or both.

A limitation of the study is the reliance on self-report measures, which are less accurate than the use of sleep assessment technology. The measure of length of nighttime sleep may not reflect actual sleep duration for a prolonged period of time in those who wake up in the midst of the sleep cycle. Our study did not inquire about length of wakeup time, a variable that should be examined in future research. Although using sleep assessment technology may be helpful in measuring the duration of night awakenings, it is difficult to use in large representational studies such as this one. In addition, data relating to nap duration or daytime rest without sleep were unavailable. Finally, it is noteworthy that despite the higher percentage of participants of Eastern/North African origin reporting long nighttime sleep duration, a protective effect on mortality was found for this country of origin. In future studies, it would be interesting to examine the potency of reported effects of long nighttime sleep and napping by country of origin.

In summary, our findings are novel in demonstrating the protective effect of short nighttime sleep in those who take daily naps and suggest that the examination of the effect of sleep needs to take into account sleep duration per 24 hr, rather than daytime napping or nighttime sleep per se. To our knowledge, we are the first to report a combined effect of nighttime sleep duration and napping status in a sample of both sexes including participants as old as 94 yr. Our study is limited by a relatively small sample for a mortality study of an interaction effect. Therefore, future studies of a larger scale are needed to replicate our analysis and also to examine sex- and age- specific trends relating to the interaction between napping status, nighttime sleep, and mortality in larger samples of older persons.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Aging Study (CALAS) was supported by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (grants R01-AG05885-03 and R01-5885-06). The above mentioned source of funding had no role in study design and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing of the article and the decision to submit it for publication.

Footnotes

A commentary on this article appears in this issue on page 903.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cappuccio FP, D'Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33:585–92. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallicchio L, Kalesan B. Sleep duration and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. 2009;18:148–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikehara S, Iso H, Date C, et al. Association of sleep duration with mortality from cardiovascular disease and other causes for Japanese men and women: the JACC study. Sleep. 2009;32:295–301. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y. Self-reported sleep duration as a predictor of all-cause mortality: results from the JACC study, Japan. Sleep. 2004;27:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bliwise DL. Sleep in normal aging and dementia. Sleep. 1993;16:40–81. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foley DJ, Vitiello VM, Bliwise DL, Ancoli-Israel S, Monjan AA, Walsh JK. Frequent napping is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness, depression, pain, and nocturia in older adults: findings from the National Sleep Foundation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:344–50. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000249385.50101.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metz ME, Bunnell DE. Napping and sleep disturbances in the elderly. Fam Pract Res J. 1990;10:47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bursztyn M, Ginsberg G, Hammerman-Rozenberg R, Stessman J. The siesta in the elderly: risk factor for mortality? Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1582–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.14.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bursztyn M, Stessman J. The siesta and mortality: twelve years of prospective observations in 70-year-olds. Sleep. 2005;28:345–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman AB, Spiekerman CF, Enright P, et al. Daytime sleepiness predicts mortality and cardiovascular disease in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:115–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone KL, Ewing SK, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Self-reported sleep and nap habits and risk of mortality in a large cohort of older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:604–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan TY, Lan TH, Wen CP, Lin YH, Chuang YL. Nighttime sleep, Chinese afternoon nap, and mortality in the elderly. Sleep. 2007;30:1105–10. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grandner MA, Hale L, Moore M, Patel NP. Mortality associated with short sleep duration: the evidence, the possible mechanisms, and the future. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walter-Ginzburg A, Shmotkin D, Blumstein T, Shorek A. A gender-based dynamic multidimensional longitudinal analysis of resilience and mortality in the old-old in Israel: the Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Aging Study (CALAS) Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1705–15. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shmotkin D, Lerner-Geva L, Cohen-Mansfield J, et al. Profiles of functioning as predictors of mortality in old age: the advantage of a configurative approach. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen-Mansfield J, Shmotkin D, Hazan H. The effect of homebound status on older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2358–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen-Mansfield J, Perach R. J Aging Res. 2011. Is there a reversal in the effect of obesity on mortality in old age? p. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz S, Downs T, Cash H, Grotz R. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10:20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawton M, Brody E. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruigomez A, Alonso J, Anto JM. Relationship of health behaviours to five-year mortality in an elderly cohort. Age Ageing. 1995;24:113–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/24.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grandner MA, Drummond SPA. Who are the long sleepers? Towards an understanding of the mortality relationship. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:341–60. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel RS, Ayas NT, Malhora MR, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and mortality risk in women. Sleep. 2004;27:440–4. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hublin C, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J. Sleep and mortality: a population-based 22-year follow-up study. Sleep. 2007;30:1245–54. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goto A, Yasumura S, Nishise Y, Sakihara S. Association of health behavior and social role with total mortality among Japanese elders in Okinawa, Japan. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15:443–50. doi: 10.1007/BF03327366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dew MA, Hoch CC, Buysse DJ, et al. Healthy older adults' sleep predicts all-cause mortality at 4 to 19 Years of follow-up. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:63–73. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000039756.23250.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naska A, Oikonomou E, Trichopoulou TP, Trichopoulos D. Siesta in healthy adults and coronary mortality in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:296–301. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bursztyn M, Ginsberg G, Stessman J. The siesta and mortality in the elderly: effect of rest without sleep and daytime sleep duration. Sleep. 2002;25:187–91. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burazeri G, Gofin J, Kark JD. Siesta and mortality in a Mediterranean population: a community study in Jerusalem. Sleep. 2003;26:578–84. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalandidi A, Tzonou A, Toupadaki N, et al. A case-control-study of coronary heart disease in Athens, Greece. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21:1074–80. doi: 10.1093/ije/21.6.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campos H, Siles X. Siesta and the risk of coronary heart disease: results from a population-based, case-control study in Costa Rica. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:429–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Youngstedt SD, Kripke DF. Long sleep and mortality: rationale for sleep restriction. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:159–74. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]