Abstract

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a key suppressor of inflammation in chronic infections and in cancer. In mice, the inability of the immune system to clear viral infections or inhibit tumor growth can be reversed by antibody-mediated blockade of IL-10 action. We used a modified selection protocol to isolate RNA-based, nuclease-resistant, aptamers that bind to the murine IL-10 receptor. After 5 rounds of selection high-throughput sequencing (HTS) was used to analyze the library. Using distribution statistics on about 11 million sequences, aptamers were identified which bound to IL-10 receptor in solution with low Kd. After 12 rounds of selection the predominant IL-10 receptor-binding aptamer identified in the earlier rounds remained, whereas other high-affinity aptamers were not detected. Prevalence of certain nucleotide (nt) substitutions in the sequence of a high-affinity aptamer present in round 5 was used to deduce its secondary structure and guide the truncation of the aptamer resulting in a shortened 48-nt long aptamer with increased affinity. The aptamer also bound to IL-10 receptor on the cell surface and blocked IL-10 function in vitro. Systemic administration of the truncated aptamer was capable of inhibiting tumor growth in mice to an extent comparable to that of an anti- IL-10 receptor antibody.

Introduction

Inflammation-suppressing pathways play a key role in attenuating pathogen-directed immune responses in order to prevent autoimmune pathologies. Immune suppressive pathways are also critical for the establishment of chronic infections and are associated with a poor ability of naturally occurring or vaccine-induced immune response to eradicate tumors.1,2

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a key mediator of immune suppression during pathogenic infection.3,4,5 Inhibiting IL-10 function with an anti-IL-10 receptor antibody was sufficient to cure mice chronically infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus.6,7 IL-10-mediated immune suppression is likely to play a similar key role in human chronic infectious diseases. Elevated levels of IL-10 were observed in several chronic infectious diseases4,5 including HIV-infected patients,8 and neutralization of IL-10 in peripheral blood mononuclear cell from HCV- or HIV-infected patients enhanced viral T-cell responses in vitro.9,10,11 Cancer is also a chronic disease which elicits, albeit a dysfunctional, immune response.2 Elevated levels of IL-10 are often seen in the plasma of cancer patients which is a prognostic factor for cancer progression (reviewed in ref. 5), and blocking IL-10R in murine tumor models was shown to inhibit tumor growth.12,13,14 IL-10 can be also induced during (suboptimal) vaccination and thereby limit its effectiveness. Indeed, neutralization of IL-10 action in conjunction with vaccination enhanced the potency of vaccination.15 Arguably, IL-10 blockade in the setting of chronic infectious diseases and cancer may be of considerable therapeutic benefit.

In view of a paucity of pharmacological inhibitors or antibody-neutralizing clinical agents, we sought to develop oligonucleotide aptamers capable of binding and blocking the function of IL-10 receptor. Short oligonucleotide (ODN) aptamer ligands with high specificity and avidity to their target can be generated in a procedure known as systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX).16,17 The standard SELEX protocol consist of 12–18 rounds of binding and partitioning and PCR amplification of the target-bound ODNs until the binding aptamers comprise over 5% of the library, at which point the individual members are cloned, sequenced, and their binding specificity and affinity is determined. The SELEX protocol is labor-intensive and frequently fails to identify high-affinity aptamer binders due to process-related bias of the selection protocol. A chief, yet so far theoretical, concern is that the repeated rounds of PCR amplification select for low-affinity binders that exhibit superior PCR amplification properties or that high-affinity binders will be poorly represented due to a PCR disadvantage. Accordingly, reducing the number of selection rounds would reduce the process-related selection pressure and preserve the higher affinity-binding aptamers.

In a recent study Cho et al. have used high-throughput sequencing (HTS) to sequence ODN libraries obtained after three or more rounds of selection.18 Given the large number of sequences that can be obtained and analyzed, the progressive enrichment of specific and related sequences, though still constituting <0.1% of the total population, could be readily identified. Subsequent analysis has confirmed that many of the enriched sequences exhibited high affinity and specific binding to their target. Using the Illumina platform for HTS, we have used 5 rounds of selection to isolate high-affinity RNA-based, nuclease-resistant, aptamers that bind to and block the function of murine IL-10R. Nucleotide (nt) substitutions analysis of a high-affinity IL-10R-binding member was used to determine its secondary structure and perform a rational optimization yielding a shorter aptamer with improved binding and biological activity.

Results

Identification of high-affinity aptamers by HTS after 5 rounds of selection

Since the murine IL-10-specific α-chain of the IL-10 receptor (IL-10R) was not commercially available as tagged protein, a 40-nt random RNA library was selected against plate-bound IL-10Rd α protein using the conditions shown in Supplementary Table S1. Five rounds of selection followed by bidirectional HTS using the Illumina SOLEXa platform yielded over 11 million sequences. After discarding sequences with mismatches in the constant regions and with random regions that differed in length from 40 nts, 8.3 × 106 sequences (Supplementary Table S2) were analyzed for frequency distribution of the random N40 part. 295,540 (10.4%) sequences were represented between 2 and 100 times. 254 sequences were represented >100 times, 24 sequences present over 1,000 times, and one sequence was represented in 283,345 copies.

Sequences represented by 100 copies or more could be grouped into four major families (A-D). Sequences with no similarity to any other identified sequence families were designated as “orphans.” Each family was represented by a single, presumably “founder,” sequence present at high frequency, 1–2 sequences were present at approximately fourfold lower frequency, whereas the majority of the sequences were present at a 100-fold lower frequency (Table 1 and Figure 1a). Most members of each family differed by 1–2 nt substitutions, however, few members of B and C families, though closely similar to the “founder” sequence had significant portion of substitutions, denoted as Bw and Cw, respectively. A simulated evolution tree for each family revealed that none of the sequences analyzed had double substitutions occurring simultaneously (data not shown). For example as shown in Table 1, R5A3 sequence differed in two positions (T40G and A34G) compared from the “founder” R5A0 sequence but had only one substitution, A34G compared to R5A1 sequence, suggesting that R5A1 was the parent sequence for R5A3. An analysis of these substitutions indicates an AT:GC and GC:AT preference rather than a random pattern (Supplementary Figure S1). None of the substitutions were to complementary nucleotides, and purine-to-purine and pyrimidine-to-pyrimidine substitutions occurred significantly more frequently. Interestingly, cytosine was affected approximately twice as frequently as the other 3 nts. These data suggest that the pattern of substitution is likely due to errors by the Taq polymerase,19 which has a preference for AT:GC and GC:AT transitions.

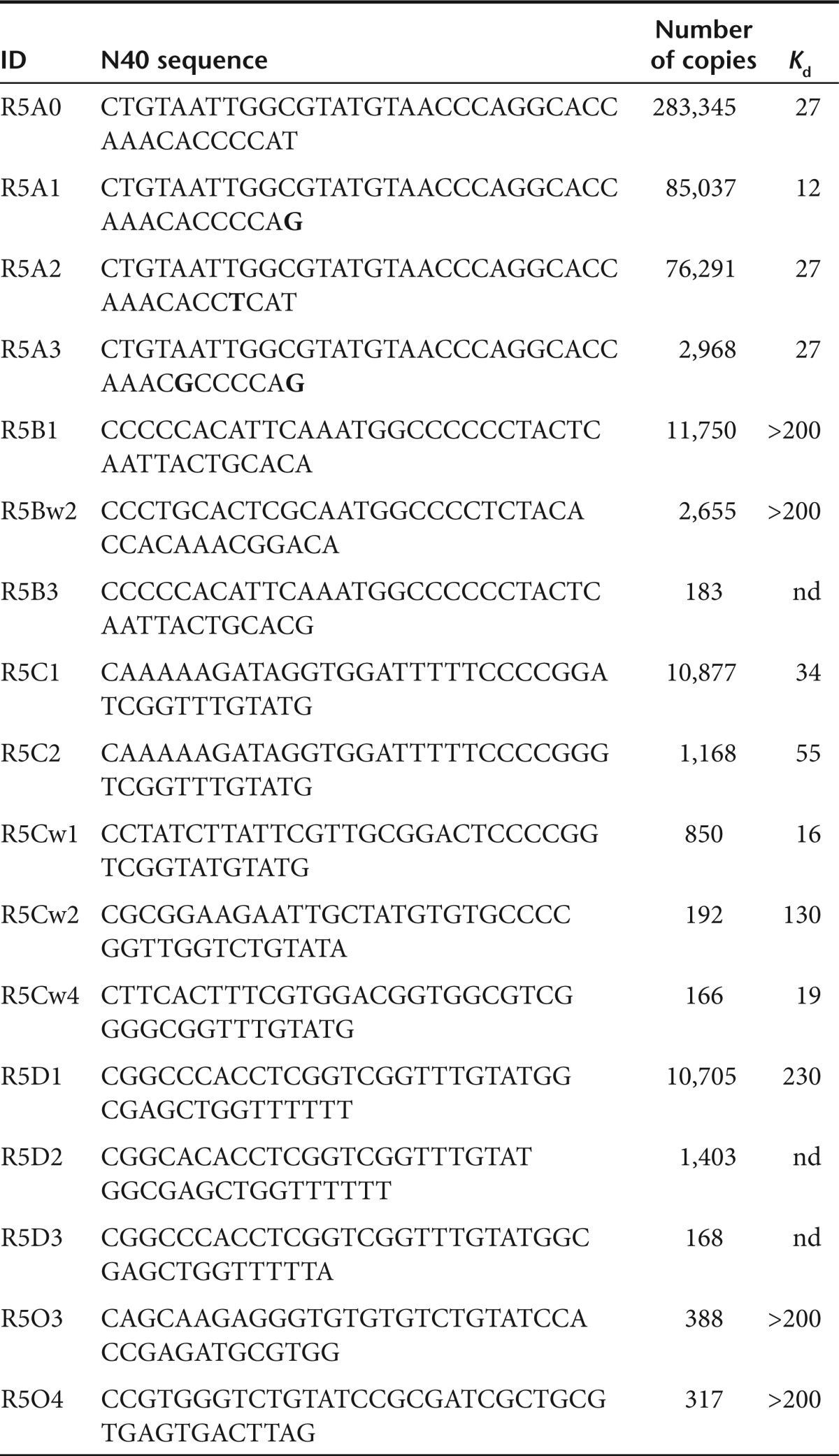

Table 1. Distribution of individual sequences after 5 rounds of selection.

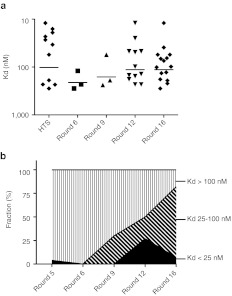

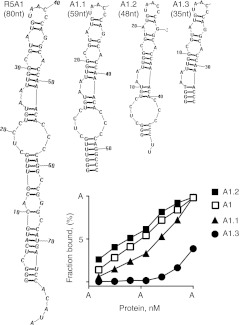

Figure 1.

Characterization of aptamers following 5 rounds of selection. (a). Frequency of aptamers represented over 100 times. 8.3 × 106 aptamers analyzed were grouped into four families of related sequences (A–D) as well as orphan aptamers that did not exhibit significant sequence similarities to other aptamers. The scale on the right y-axis corresponds to frequencies (copy number) of family A and the scale on the left y-axis corresponds to the frequencies of families B, C, D, and orphans. (b) Affinity of selected aptamers determined by the double filter-binding assay.20 Specific aptamers shown in panel a that were analyzed in panel b are indicated in red or blue color.

To determine if frequency of representation reflects enhanced binding to IL-10R, we measured the binding affinity of representative members of each family using the double filter-binding assay.20 As shown in Figure 1b, aptamers belonging to families A and C bound to IL-10R with high affinity (Kd ~10–30 nmol/l) while all orphan sequences and family B or D aptamers failed to bind to IL-10R.

Loss of high-affinity aptamers during selection

Standard SELEX protocol requires 12–18 rounds of selection to enrich for high-affinity aptamers that can be identified by standard cloning/sequencing. To compare the aptamers identified by the standard cloning/sequencing and HTS sequencing, we continued the selection beyond round 5 for additional 11 rounds. After 6, 9, 12, and 16 rounds, libraries were cloned, sequenced, and individual aptamers were tested for binding affinity to IL-10R (Figure 2a and Table 2). Round 6 and 9 aptamers exhibited weak binding to IL-10R. At round 12, the library contained a number of aptamers binding IL-10R with Kd ranging from 12 to 98 nmol/l. The most abundant aptamer in this library with highest affinity to IL-10R, R12#116, was identical to the highest affinity IL-10R-binding aptamer from round 5 library, R5A1, shown in Figure 1. Continuing selection for four additional rounds for a total of 16 rounds led to decrease in the frequency of the high-affinity R12#116/R5A1 aptamer whereas another aptamer, R16#201 that exhibited moderate affinity to IL-10R was enriched. Strikingly, other high-affinity aptamers identified by HTS at round 5 such as R5Cw1 and R5Cw4 were not detected after 12 or 16 round of selection by cloning/sequencing. Thus, repeated cycles of selection resulted in the gradual loss of high-affinity aptamers and the emergence of intermediate to low-affinity aptamers. (Figure 2b). One explanation for the emergence of lower affinity aptamers at later rounds of selection and the concomitant loss of higher affinity aptamers present at round 5 (e.g., R5A1 and R5Cw1) is that the former enjoy a competitive advantage during PCR amplification. A second, mutually not exclusive, explanation is that the highest affinity R5A1/R12#116 aptamer competes with other high-affinity aptamers for the same binding site on IL-10R whereas the aptamers enriched in later rounds bind to another site on IL-10R. Consistent with this possibility, as shown in Supplementary Figure S2,the high-affinity R5A1 aptamer competed with other aptamers identified in round 5, A0, Cw1, but not with an aptamer, R12#107 identified after 12 rounds of selection. Since the round 5 R5A1 aptamer and round 12 R12#107 aptamers appear to bind to different epitopes of IL-10Rα, this could explain how a lower affinity aptamer like R12#107 aptamer was selected after 12 rounds, while other higher affinity aptamers, like A0, Cw1, that competed for binding with R5A1, became extinct.

Figure 2.

Affinity distribution of aptamers following increasing rounds of selection. (a) Affinity of aptamers identified by high-throughput sequencing (HTS) after 5 rounds of selection and sequencing/cloning after rounds 6, 9, 12, and 16. (b) Frequency distribution of high (black), medium (diagonal lines), and low (vertical lines) affinity aptamers with increasing rounds of selection.

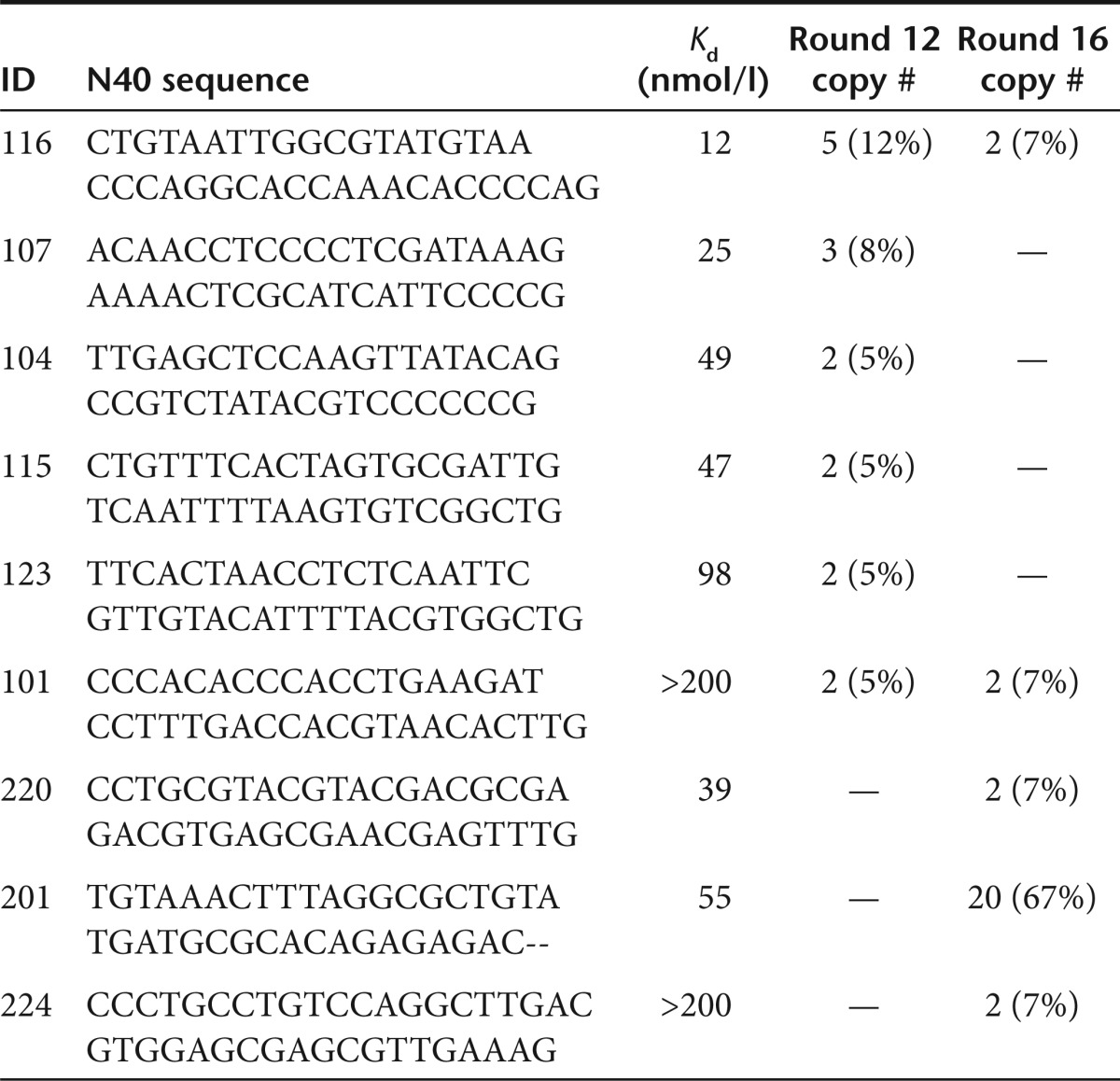

Table 2. Aptamers present at multiple copies at rounds 12 and 16.

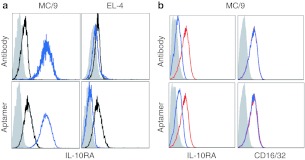

R5A1 aptamer binds IL-10Rα on the cell surface

The IL-10R-binding aptamers were selected against plate-bound IL-10R and were shown to bind with high affinity to IL-10R protein in solution (Figure 1b and Table 1). To determine if the aptamers bind to IL-10R expressed on the cell surface we used flow cytometry to measure the binding of fluorophore-labeled R5A1 aptamers to the IL-10Rα-expressing MC/9 cells. Since monovalent aptamers bind poorly to their cognate target on the cell surface21 we generated a tetravalent, phycoerythrin-labeled R5A1 aptamer. As shown in Figure 3a, the 1B1.3a monoclonal anti-IL-10Rα antibody and the tetravalent R5A1 aptamer bound to MC/9 cells but not to the IL-10R negative EL-4 cells. To confirm that the R5A1 aptamer binds to IL-10R, and not to another product expressed on the surface of MC/9 cells, Figure 3b shows that the binding of anti-IL-10R antibody, but not the unrelated anti-CD16/32 antibody, could be competed with an excess of either polyclonal anti-IL-10R antibody or with R5A1 aptamer. Furthermore, the IL-10R-binding R5A1, but not the R5B1 nonbinding, aptamer competed with anti-IL-10R antibody in a dose-dependent manner for binding to IL-10R (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Binding of a tetrameric form of the high-affinity R5A1 aptamer to interleukin-10R (IL-10R) expressed on the cell surface. (a) Phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-IL-10R 1B1.3a antibody or tetrameric R5A1 (blue) and isotype control antibody or control aptamer (black) were incubated with IL-10R-expressing MC/9 cells and EL-4 cells which do not express IL-10R, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (b) MC/9 cells were pretreated with polyclonal anti-IL-10R antibody or R5A1 aptamer (blue), or with anti-goat polyclonal antibody or with scrambled aptamer (red). Precoated cells were then incubated with PE-labeled anti-IL-10R or anti-CD16/32 antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry.

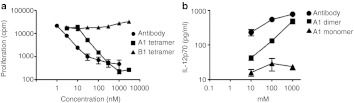

A tetrameric form of R5A1 aptamer blocks IL-10 signaling in vitro

To determine whether binding of the high-affinity R5A1 aptamer can inhibit the biological function of IL-10R, we determined whether the R5A1 aptamer can inhibit the proliferation of the IL-10-dependent murine MC/9 mast cells.22 As shown in Figure 4a, tetravalent R5A1 aptamers and anti-IL-10R antibodies, but not the nonbinding tetrameric R5B1 aptamer, inhibited the IL-10-induced proliferation of MC/9 cells in a dose-dependent manner. The blocking activity of the R5A1 aptamer and its derivatives was also demonstrated using another commonly used assay based on rescuing IL-12 secretion by lipopolysaccharide -treated dendritic cells cultured in the presence of IL-1013 (Figure 4b). These experiments, therefore, show that binding of multivalent R5A1 aptamers to IL-10R on the cell surface inhibits IL-10R function presumably by blocking IL-10 binding to the receptor.

Figure 4.

R5A1 interleukin-10R (IL-10R)-binding aptamer inhibits IL-10 signaling in vitro. (a) Inhibition of IL-10 dependent proliferation of MC/9 cells. MC/9 cells cultured in the presence of 1 ng/ml IL-10 were incubated with increasing concentrations of either anti-IL-10 antibodies, tetrameric R5A1 aptamers or tetrameric R5B1 aptamers and proliferation was determined 48 hours later by measuring 3H-thymidine incorporation. (b) Rescue of IL-12 secretion by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated dendritic cells (DC) cultured in the presence of IL-10. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells were incubated for 6 days in presence 12 ng/ml granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and 10 ng/ml IL-4. Cells were plated in triplicates into flat-bottom 96-well plate and cultured in the presence of 100 ng/ml of LPS, 20 ng/ml interferon-γ (IFNγ), and 1 ng/ml of IL-10. As indicated anti-IL-10R antibody, dimeric R5A1 or monomeric R5A1 aptamers were added and 18 hours later supernatants were harvested and IL12p70 concentration was measured.

HTS-guided truncation of the IL-10R-binding R5A1 aptamer

During selection the 80-nt long aptamers (composed of 20 nt 3′ and 5′ constant regions, and 40 nt variable region) were transcribed from a DNA template using T7 RNA polymerase. However, production of sufficient quantities of RNA aptamer, especially for clinical use, will require chemical synthesis. Given that the practical limits of cost-effective chemical synthesis of fluoro-modified ribo-oligonucleotides is currently about 50–60 nts, the 80-nt long aptamers need to be truncated to or below this limit.

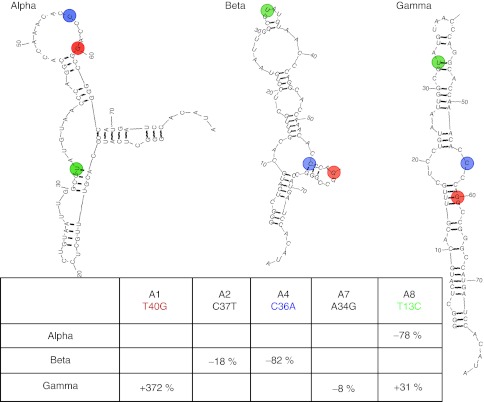

Truncation is commonly performed by deleting sequentially 3–5 nts from the 3′ and/or the 5′ end of the molecule and testing the truncated products for binding and function. A rational, and preferable, approach is truncation of the aptamer guided by its secondary structure.23 However, as is often the case, computer modeling provides multiple distinct secondary structures of comparable stability. Case in point, for the high-affinity R5A1 IL-10R aptamer three secondary structures of comparable stability were predicted by computational structure modeling (Figure 5). We used the HTS generated data set of round 5 SELEX to deduce the likely secondary structure configuration of the R5A1 aptamer. The approach was to map the nucleotide substitutions present in the five most abundant members of the A family R5A1-A5 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2) to the three putative secondary structures of R5A0. Since all five substitution-bearing variants retained high-affinity binding to IL-10R, we hypothesized that the single-nucleotide substitutions would be tolerated well or even beneficial in the correctly predicted structure, whereas some substitutions might significantly decrease the calculated stability of the incorrectly predicted secondary structures. As illustrated in the examples shown in Figure 5, this analysis has revealed that in the “alpha” configuration four out of five changes had no effect on stability whereas the T13C substitution had a destabilizing effect. Similarly, in the “beta” configuration one base change generated significantly less stable structure while four others had no effect. In contrast, three nucleotide substitutions mapping to the “gamma” configuration had no or little effect on stability, while two, T40G and T13C, had a significant stabilizing effect. This analysis, therefore, suggest that the secondary structure assumed by the A family of aptamers, including the highest affinity R5A1 aptamer, is more correctly described by “gamma” configuration. Interestingly, the most critical T40G substitution in this structure created a double-stranded stem in a middle of the molecule (configuration “gamma”), indicating the importance of this part of the aptamer for its secondary structure and binding properties.

Figure 5.

Secondary structure prediction by base-substitution analysis. Three secondary structure configurations of comparable stability were predicted for the R5A0 “founder” sequence using the RNA Structure 5.03 program (The A1 sequence is shown). Effect of substitution on stability (percent change) occurring in R5A1 (T40G), R5A2 (A34G), R5A3 (C37T), R5A4 (C36A), and R5A5 (T13C) shown in insert table. Color-coded changes are indicated in the secondary structure configuration.

Guided by the secondary structure shown in the “gamma” configuration, the 80-nt long R5A1 aptamer was truncated to yield three derivatives, the A1.1 (59 nt), 48-nt long A1.2 (48 nt), and 35 nt long A1.3 (35 nt), and tested for binding to IL-10R (Figure 6). Whereas derivative A1.1 exhibited reduced affinity compared to R5A1, additional truncation and stabilization of the terminal stem region increased the binding affinity of A1.2 above that of the parent R5A1 aptamer, suggesting that the sequences deleted from the R5A1 aptamer exerted a negative impact on its binding to IL-10R. The A1.2 aptamer did not bind to human IL-10R in solution, and did not block human IL-10 mediated inhibition of IL-12 secretion from human dendritic cells (data not shown). Additional truncation of A1.2 removing the single stranded loop region abrogated binding, indicating the critical contribution of this loop structure to IL-10R binding. Thus, guided by HTS analysis a 48-nt long truncated derivative was generated which exhibited improved binding affinity compared to the parental 80 nt long R5A1 aptamer.

Figure 6.

Secondary structure-guided truncation of the R5A1 aptamer. Truncation of R5A1 aptamer was guided by the secondary structure shown in Figure 5 as configuration gamma to yield truncate aptamers A1.1, A1.2, and A1.3. Binding to interleukin-10R (IL-10R) was determined using the double filter-binding assay. See text for additional details.

In vivo blocking of IL-10 action—inhibition of tumor growth

The truncated 48-nt long A1.2 aptamer can be synthesized chemically to provide sufficient material for in vivo testing. To reduce the cost and enhance the robustness of chemically synthesizing nuclease-resistant RNA-based aptamers we have chemically synthesized several A1.2 aptamer derivatives in which 2′ fluoro-modified pyrimidines were substituted with 2′O-methyl modified pyrimidines at various positions. While in general the 2′ O-methyl-modified aptamers exhibited reduced binding and in vitro IL-10 blocking activity, one such aptamer in which all but four fluoro-modified positions were substituted with 2′ O-methyl groups, A1.2-4FL, retained considerable, though reduced, binding and in vitro neutralizing activity as monomer (Supplementary Figure S3).

To test whether the 2′ O-methyl modified aptamer A1.2-4FL (Figure 7a) can block IL-10 activity in vivo we used an established experimental system whereby systemic administration of neutralizing anti-IL-10R antibodies was shown to inhibit CT26 tumor growth in mice by countering the local immune suppressive effects of IL-10.13 Figure 7b,c show that daily intravenous injection of neutralizing anti-IL-10R antibody or the A1.2-4FL aptamer, but not a control aptamer, led to inhibition of tumor growth measured 4 days later. Repeated injections of aptamer or antibody led to the rejection of the subcutaneously implanted tumors in 20% of the treated animals (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 7.

Interleukin-10R (IL-10R) aptamer-mediated inhibition of tumor growth. (a) The 48-nt long A1.2 aptamer was synthesized chemically with all but four of the 2′fluoro-modified pyrimidines (red) replaced with 2′ O-methyl-modified pyrimidines (green). Balb/c mice were implanted with 1.0 × 105 live CT26 cells. Ten days later mice were injected intratumorally at day 10, 11, and 12 with 10 µg of CpG oligonucleotide and intraperitoneally with 100 µg of anti-IL-10R 1B1.3a antibody, or intravenously with 30 µg of A1.2-4FL aptamer or with scrambled aptamer. (b) Tumor area measured at the days indicated. Arrows indicated day of treatment with antibody or aptamer. Difference between scrambled aptamer and A1.2-4FL aptamer or IBI.3a antibody treated groups.*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. (c) 72 hours after treatment animals were sacrificed and tumor were examined morphologically and weighted.

Discussion

Murine studies have underscored the potential benefits of pharmacological inhibition of IL-10 function in models for chronic infections and cancer. Given the paucity of clinically useful agents to block IL-10 function and the challenges in generating clinical grade monoclonal antibodies,24 we are exploring the use of oligonucleotide aptamers which, unlike antibodies, can be synthesized in a chemical process and hence offer significant advantages in terms of reduced production cost and simpler regulatory approval process. In this study we described the isolation of a high-affinity, nuclease-resistant, oligonucleotide aptamer ligand that binds to murine IL-10 receptor in solution and on the cell surface, and inhibits IL-10 function in cell culture. Underscoring one advantage of oligonucleotide aptamer ligands, several straightforward methods were used to generate bivalent and tetravalent aptamer derivatives, which exhibited enhanced binding affinity and improved biological activity comparable to that of a monoclonal anti-IL-10R antibody. An optimized monovalent aptamer, though less potent than multivalent derivatives or the anti-IL-10R antibody, was sufficiently potent to inhibit tumor growth in mice.

Using HTS to analyze the library of aptamers after 5 rounds of selections provided sufficient sequence information to identify high-affinity binders otherwise requiring 12 rounds of selection on standard SELEX protocol. Distribution statistics of four families of related sequences two of which bound to IL-10R provided valuable insights into the selection process. Families comprised of an apparent “founding” member present at very high frequency that gave rise to first and second generation of progeny with one or two single-nucleotide substitutions, respectively. The substitutions pattern, except for a higher frequency of cytosine substitutions, was consistent with the AT:GC and GC:AT transition predisposition of Taq polymerase. Thus, many of the high affinity-binding aptamers we observed were likely to have been derived from a preexisting low to intermediate affinity “founder” aptamer through mutations during the PCR amplification reaction, rather than by selection of preexisting high-affinity aptamers.

In addition to significant reductions in time and cost, HTS-based analysis of early rounds of selection offers additional important advantages. Analysis of multiple rounds of selection using the standard cloning procedures to characterize individual aptamers for binding to IL-10R has shown that there is a gradual loss of high-affinity aptamers. For example, only the highest affinity R5A1 aptamer identified by HTS in round 5 was also present in round 12 but not in earlier rounds, conceivably its frequency must have been below the limited number of aptamers that can be characterized by cloning and sequencing. Nonetheless, the relative frequency of the R5A1 aptamer was diminished after 16 rounds of selection, and two aptamers R5Cw1 and R5Cw4 with Kd <20 nmol/l were eliminated altogether, replaced by lower affinity R12#107, 115, 104 aptamers with Kd ranging from 25 to 100 nmol/l. Considering the limitation of sequencing through cloning (e.g., necessity for certain aptamer sequence to be compatible with bacterial machinery) it is possible that these aptamers are still present in the round 6–16 libraries. As summarized in Figure 2b, while the proportion of high-affinity aptamers, detectable after 5 rounds of selection by HTS but only after 12 rounds of selection by standard protocol, peaked at round 12 and (some) became extinct at later rounds, the fraction of aptamers with moderate binding affinity increased steadily during the 16 rounds of selection. A possible explanation for the selective advantage of the moderately binding aptamers is that they exhibit a PCR amplification advantage. Thus in the worst case, standard selection protocols that require 12 or more rounds of selection could fail to identify under-represented high-affinity candidates. These observations, therefore, underscore the benefits of analyzing libraries from earlier rounds of selection to identify high-affinity aptamers.

Another useful feature of HTS analysis of early rounds of selection is to guide the truncation of selected aptamers. Truncation of aptamers is necessary to facilitate their cost-effective chemical synthesis that is a prerequisite for clinical applications. Using distribution statistics of base substitutions in the A family enabled us to predict the likely secondary structure of the 80-nt long high-affinity R5A1 aptamer, choosing from three distinct configuration of comparable stability predicted by the computer program, and guide the rationale truncation strategy to yield a 48-nt long derivative, A1.2. Interestingly, the truncated A1.2 aptamer exhibited superior binding compared to its parental R5A1 aptamer conceivably as a result of the removal of an inhibitory sequence. Of note, the standard and labor-intensive truncation strategy of removing sequentially ~5 nt from the 5′ or 3′ ends of the long aptamer would have failed to generate binding variants.

In summary, HTS-based analysis of early rounds of selection to isolate aptamer ligands offers significant advantages in terms of time and cost as compared to the standard labor-intensive SELEX procedure requiring multiple rounds of selection, helps identifying high-affinity binders that can be lost during subsequent rounds of selection, and guides the rational truncation of the selected aptamers.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of aptamer by systemic evolution of ligand by exponential enrichment. 80-nt long RNA library 5′-GGGCUCAUGCACGUUUG CUC(N40)GCCGGGCCAUGAUCCACAUA-3′ was used for selection. RNA was transcribed from DNA template using Durascribe T7 transcription kit (Epicenter, now Illumina, Madison, WI) and purified by 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Purified RNA was folded by heating to 82 °C 5′ in selection buffer (150 mmol/l NaCl, 20 mmol/l KCl, 20 mmol/l HEPES) and cooling slowly to room temperature (RT). Tween-20 (0.01%) and bovine serum albumin (0.1% final concentrations) were added to RNA solution immediately prior binding step. 96-well MaxiSorp (Nunc, Rochester, NY) plate was coated with soluble recombinant murine IL-10RA protein (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in 50 µl phosphate-buffered saline for 18 hours at +4 °C. Each well was blocked with 300 µl of 1% bovine serum albumin in selection buffer for 1 hour at RT. To preclear the library, RNA was incubated in bovine serum albumin-coated wells for 30′. Precleared RNA was added to IL-10Rα-coated wells and incubated for 15′ at +37 °C. Unbound RNA was removed and wells were washed six times with 37 °C selection buffer at 37 °C. Bound RNA was recovered by washing wells with RLT buffer and purification by RNeasy MinElute kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Reverse transcription was carried by annealing 5′-TATGTGGATCATGGCCCGGC-3′ oligo and extension with AMV RT (Promega, Madison, WI). Oligonucleotides: 5′-AATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTCATGCACGTTTGCTC-3′ and 5′-TATGTGGATCATGGCCCGGC-3′ was used to amplify complementary DNA and get DNA template for transcription.

Nitrocellulose-nylon double-layer binding assay. Kd of libraries and individual aptamers were determined as described in ref. 25. Seventy five nanogram of RNA dephosphorylated by Calf Intestinal Alkaline Phosphotase (Promega) was labeled with T4 PNK (Promega) using 32P-gamma ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol) and purified on G25 Sephadex columns (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). RNA was adjusted to 5,000 CPM/µl and folded by heating to 85 °C in selection buffer. Serial dilutions of IL-10Rα protein starting from 330 nmol/l were made in selection buffer supplied with 0.01% bovine serum albumin. Five microliter of RNA was incubated with 15 µl of protein for 5 minutes at 37 °C, filtered through Nitrocellulose (top) and Nylon (bottom) double-filters using dot-blot apparatus (Nalgene, Rochester, NY). CL-X film was exposed by membranes for 18 hours at RT. ImageJ 1.38× software (Wayne Rasband; NIH, Bethesda, MD) was used to determine relative optical density of radiographed spots in NC-filter binding assay, these data been used to calculate amount of radioactive RNA in each spot.

Sequencing. At rounds 6, 9, 12, and 16 DNA template library was cloned into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega) and clones were sequenced individually. Round 5 DNA template library was sequenced by Illumina GS2 machine using one flow cell in 75-nt paired end run. To prepare the library for sequencing complementary DNA generated from RNA bound at round 5 was amplified with 100 nmol/l oligonucleotides 5′-ACACTC TTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTGGGCTCATGCACG TTTGCTC-3′ and 5′-CTCGGCATTCCTGCTGAACCGCTCTTCCGAT CT TATGTGGATCATGGCCCGGC-3′ for 10 (95-60-72) cycles. Later Illumina adapters 5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCT TTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′ and 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACG GCATACGAGATCGGTCTCGGCATTCCTGCTGAACCGCTC TTCCGATCT-3′ were added directly to PCR mixture to final concentration of 1 µmol/l and 6 more (95-65-72) PCR cycles were performed. Two hundred base pair band was purified from 2% agarose gel by kit (Qiagen) after electrophoretic separation.

Generation and modification of RNA aptamers. DNA oligonucleotides 5′-AATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTCATGCACGTTTGC TC (40 nt) GCCGGGCCATGATCCACATA-3′ and its complement was obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Two complementary oligonucleotides were annealed at final concentration of 10 µmol/l each by heating to 94 °C in 1× PCR buffer and cooling down slowly to RT. Double-stranded DNA was purified by PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and used as template for in vitro transcription with Durascribe T7 kit (Epicentre, now Illumina). For cell surface staining experiments aptamers were conjugated with biotin-(LC)2-malemide using 5′-end labeling kit (Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA). Ten microgram of biotinylated aptamers were incubated with 1 µg of Streptavidin-R-phycoerythrin conjugate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) in 100 µl phosphate-buffered saline 15′ at RT. Complex formation was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Formed tetramers were purified by triple centrifugation through 100 kDa MWCO column (PALL, Port Washington, NY).

For in vitro IL-10R blocking experiments R5A1 aptamer was dimerized through dPEG linker (Quanta Biogesign, Powell, OH). Nucleotide analog ATP-gamma-S (Vector Lab) was incorporated on 5′-end by T4 PNK. Labeled RNA was purified by size-exclusion column and one half of material was conjugated (65 °C for 45′) to BisMAL-dPEG3 with RNA-to-linker ratio 1:1,000. Conjugated RNA-dPEG3-MAL monomers were repurified and conjugated with remaining labeled RNA. Resulting dimers was purified by 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. A1.2-4FL aptamer for in vivo studies was custom synthesized by IDT (Iowa City, IA).

BMDCs isolation and IL-10 inhibition assay. Dendritic cell precursors were isolated from bone marrow of tibias of 6-week-old B6 female mice. Red blood cells was lysed by ACK solution and white blood cells were plated into 6-well plate at concentration of 106 cells/ml 5 ml/well in complete growth media (RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum, MEM essential and nonessential amino acids, Na pyruvate and 2-ME) supplemented with 12 ng/ml rmGM-CSF and 10 ng/ml rmIL-4 (R&D Systems). Growth media was changed at day 3 and at day 6 suspension cells were collected, washed and plated to 96-well plate 105 cells/well in 100 µl. Twenty-four hours later aptamers, phosphate-buffered saline, or polyclonal m IL-10Rα-binding antibody (R&D Systems) was added to each wells for 20′ to block IL-10Rα. IL-10 was added to final concentration of 1 ng/ml and incubated with cells for another 20′. Cells were activated with 100 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide (Sigma) and 20 ng/ml interferon-γ (R&D Systems) and media volume was adjusted to 200 µl /well. After 18 hours of incubation supernatants from each well were analyzed for IL12p70 by ELISA (R&D Systems).

MC/9 cells and IL-10 stimulation assay. MC/9 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media with 10% fetal bovine serum, MEM essential and nonessential amino acids, Na pyruvate and 2-ME, and 10% T-STIM growth supplement (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Five hours before assay cells were washed twice in RPMI-1640 media without T-STIM and seeded into 96-well plate 104 cells in 100 µl. Aptamers or polyclonal antibody against IL-10Rα (R&D Systems) were added to each well and incubated for 20′ to block IL-10Rα. After incubation with RNA or PAB recombinant IL-10 was added to final concentration of 5 ng/ml and volume was adjusted to 200 µl/well. Fourty-eight hours later 1 µCi of 3H-thymidine was added to each well in 50 µl of RPMI-1640 media and cells were incubated overnight at 37 °C in CO2 incubator. Incorporation of 3H-thymidine was determined by liquid scintillation on Wallac micro-beta counter (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA).

Mice and in vivo tumor immunotherapy experiments. Eight-week-old female Balb/c mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). 105 CT26 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously in the right flank. Ten days after injection CT26 tumors were measured and mice were randomized to receive 30 µg of A1.2-4FL aptamer or control RNA intravenously, or 100 µg of anti-IL-10Rα 1B1.3a antibody (Harlan, Frederick, MD) intraperitoneally. All animals also received intratumoral injection of 10 µg of 1,668 CpG oligonucleotide (InVivoGen, San Diego, CA). 24, 48, and 72 hours after treatment tumors were measured by caliper. Seventy two hours after injection animals were sacrificed. Tumors were removed and weighted. GraphPad Prism 5.1 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used to represent these data and all other graphs throughout the article.

NGS dataset processing and analysis. Base calls in Sanger format were aligned between forward and reverse reads for each sequence; those containing mismatches were excluded. The resulting dataset was filtered to select only sequences with perfect matches to the known constant regions and 40-nt length of the N40 variable region. Families were identified as groups of similar sequences that were within three mismatches to the most represented. Sequences with no similarity to any of the identified sequence families were designated as orphans. Most represented members of each family and all orphans were compared using ClustalW alignment and analyzed for phylogeny using MacVector 9.2 (MacVector, Cary, NC). If different families had significant of homology within the N40 variable region, the less represented family was included as a subfamily within the major family.

Computational structure modeling for A1 aptamer sequence. RNAstructure 5.03 (by Mathews Lab at University of Rochester, Rochester, NY) used to predict RNA aptamers secondary structure—most current at time of analysis. Most probable structures were determined for R5A1 aptamer and designated as “alpha”, “beta,” and “gamma”. A0, A2, A3, A4, and A5 sequences had been searched for ability to fold in same “alpha”, “beta,” and “gamma” conformations using suboptimal structure generation option. Energy prediction for each structure had been used as criteria of stability for comparison. Stability of R5A0 aptamer in each of those conformations had been used as baseline. Difference (if any) in minimal energy predictions for each structure between A0 and each A1, A2, A3, A4, and A5 aptamers had been expressed as percentages in the table.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Nucleotide substitutions in the A family after 5 rounds of selections. Figure S2. The R5A1 aptamer does not compete with other aptamers for binding to IL-10R. Figure S3. Effect of 2′-O-methyl substitutions on the binding affinity of A1.2 aptamer. Figure S4. Inhibition of tumor growth in mice treated with CpG ± anti-IL-10R Ab or aptamer. Table S1. SELEX conditions. Table S2. Round 5 SELEX.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nadezhda Tarasova for advice PEG conjugations. Authors declare no commercial affiliation, consulting arrangements, stock, equity, or any other potential financial conflict of interest. Funding was provided by a bequest from the Dodson estate and the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center (Medical School, University of Miami).

Supplementary Material

Nucleotide substitutions in the A family after 5 rounds of selections.

The R5A1 aptamer does not compete with other aptamers for binding to IL-10R.

Effect of 2′-O-methyl substitutions on the binding affinity of A1.2 aptamer.

Inhibition of tumor growth in mice treated with CpG ± anti-IL-10R Ab or aptamer.

SELEX conditions.

Round 5 SELEX.

REFERENCES

- Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:492–499. doi: 10.1038/ni.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitvogel L, Tesniere A., and, Kroemer G. Cancer despite immunosurveillance: immunoselection and immunosubversion. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:715–727. doi: 10.1038/nri1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn SD., and, Wherry EJ. IL-10, T cell exhaustion and viral persistence. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couper KN, Blount DG., and, Riley EM. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:5771–5777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL., and, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejrnaes M, Filippi CM, Martinic MM, Ling EM, Togher LM, Crotty S.et al. (2006Resolution of a chronic viral infection after interleukin-10 receptor blockade J Exp Med 2032461–2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DG, Trifilo MJ, Edelmann KH, Teyton L, McGavern DB., and, Oldstone MB. Interleukin-10 determines viral clearance or persistence in vivo. Nat Med. 2006;12:1301–1309. doi: 10.1038/nm1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockman MA, Kwon DS, Tighe DP, Pavlik DF, Rosato PC, Sela J.et al. (2009IL-10 is up-regulated in multiple cell types during viremic HIV infection and reversibly inhibits virus-specific T cells Blood 114346–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accapezzato D, Francavilla V, Paroli M, Casciaro M, Chircu LV, Cividini A.et al. (2004Hepatic expansion of a virus-specific regulatory CD8(+) T cell population in chronic hepatitis C virus infection J Clin Invest 113963–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigopoulou EI, Abbott WG, Haigh P., and, Naoumov NV. Blocking of interleukin-10 receptor–a novel approach to stimulate T-helper cell type 1 responses to hepatitis C virus. Clin Immunol. 2005;117:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Valdés N, Manterola L, Belsúe V, Riezu-Boj JI, Larrea E, Echeverria I.et al. (2011Improved dendritic cell-based immunization against hepatitis C virus using peptide inhibitors of interleukin 10 Hepatology 5323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiducci C, Vicari AP, Sangaletti S, Trinchieri G., and, Colombo MP. Redirecting in vivo elicited tumor infiltrating macrophages and dendritic cells towards tumor rejection. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3437–3446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicari AP, Chiodoni C, Vaure C, Aït-Yahia S, Dercamp C, Matsos F.et al. (2002Reversal of tumor-induced dendritic cell paralysis by CpG immunostimulatory oligonucleotide and anti-interleukin 10 receptor antibody J Exp Med 196541–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Lee Y, Liu W, Krausz T, Chong A, Schreiber H.et al. (2005Intratumor depletion of CD4+ cells unmasks tumor immunogenicity leading to the rejection of late-stage tumors J Exp Med 201779–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DG, Lee AM, Elsaesser H, McGavern DB., and, Oldstone MB. IL-10 blockade facilitates DNA vaccine-induced T cell responses and enhances clearance of persistent virus infection. J Exp Med. 2008;205:533–541. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold L, Polisky B, Uhlenbeck O., and, Yarus M. Diversity of oligonucleotide functions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:763–797. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimjee SM, Rusconi CP., and, Sullenger BA. Aptamers: an emerging class of therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:555–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.062904.144915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M, Xiao Y, Nie J, Stewart R, Csordas AT, Oh SS.et al. (2010Quantitative selection of DNA aptamers through microfluidic selection and high-throughput sequencing Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 10715373–15378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keohavong P., and, Thilly WG. Fidelity of DNA polymerases in DNA amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9253–9257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong I., and, Lohman TM. A double-filter method for nitrocellulose-filter binding: application to protein-nucleic acid interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5428–5432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara JO, Kolonias D, Pastor F, Mittler RS, Chen L, Giangrande PH.et al. (2008Multivalent 4-1BB binding aptamers costimulate CD8+ T cells and inhibit tumor growth in mice J Clin Invest 118376–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Snipes L, Dhar V, Bond MW, Mosmann TR, Moore KW., and, Rennick DM. Interleukin 10: a novel stimulatory factor for mast cells and their progenitors. J Exp Med. 1991;173:507–510. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockey WM, Hernandez FJ, Huang SY, Cao S, Howell CA, Thomas GS.et al. (2011Rational truncation of an RNA aptamer to prostate-specific membrane antigen using computational structural modeling Nucleic Acid Ther 21299–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardoll D., and, Allison J. Cancer immunotherapy: breaking the barriers to harvest the crop. Nat Med. 2004;10:887–892. doi: 10.1038/nm0904-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layzer JM., and, Sullenger BA. Simultaneous generation of aptamers to multiple gamma-carboxyglutamic acid proteins from a focused aptamer library using DeSELEX and convergent selection. Oligonucleotides. 2007;17:1–11. doi: 10.1089/oli.2006.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Nucleotide substitutions in the A family after 5 rounds of selections.

The R5A1 aptamer does not compete with other aptamers for binding to IL-10R.

Effect of 2′-O-methyl substitutions on the binding affinity of A1.2 aptamer.

Inhibition of tumor growth in mice treated with CpG ± anti-IL-10R Ab or aptamer.

SELEX conditions.

Round 5 SELEX.