Abstract

Background

Community coalitions are increasingly recognized as important strategies for addressing health disparities. By providing the opportunity to pool resources, they provide a means to develop and sustain innovative approaches to affect community health.

Objectives

This article describes the challenges and lessons learned in building the Asian American Hepatitis B Program (AAHBP) coalition to conduct a community-based participatory research (CBPR) initiative to address hepatitis B (HBV) among New York City Asian-American communities.

Methods

Using the stages of coalition development as a framework, a comprehensive assessment of the process of developing and implementing the AAHBP coalition is presented.

Lessons Learned

Findings highlight the importance of developing a sound infrastructure and set of processes to foster a greater sense of ownership, shared vision, and investment in the program.

Conclusion

Grassroots community organizing and campus–community partnerships can be successfully leveraged to address and prevent a significant health disparity in an underserved and diverse community.

Keywords: Asian Americans, community-based participatory research, community health services, healthcare disparities, hepatitis B

HBV infection is among the leading health disparities for Asian Americans and Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (AAs and NHPIs) nationally and worldwide.1 AAs and NHPIs account for more than one half of the 1.4 million cases of chronic HBV in the United States2 and are 30 to 50 times more likely to have chronic HBV compared with Whites. This is a result of high rates of endemic HBV infection in Asia and the Pacific Islands that is transmitted primarily from mother to child or acquired early in childhood. Chronic HBV infection usually takes decades before it causes clinically systematic disease, mainly as liver failure and liver cancer. Because infection is clinically silent it is often diagnosed at a late stage of advanced liver cancer or failure when little can be done and outcomes are very poor. Approximately one in four persons with chronic HBV infection dies from their infection if it is undiagnosed and untreated. Overall, AA and NHPIs are seven times more likely to die from HBV-related complications compared with other communities in the United States.3 Most of those deaths are preventable through screening, vaccination, and early treatment.

New York City is home to the largest AA population in the United States, with 1 million AAs, representing tremendous cultural and language diversity. Between 65% and 72% of New York City’s AAs are first-generation immigrants, with high limited English proficiency rates (range, 60%–80%).4 Approximately 19% are uninsured. HBV prevalence rates range from between 3% and 22% in New York City’s AA community, varying by specific ethnic group, compared with fewer than 0.5% in the general U.S. population.1 The highest rate occurs in Chinese Americans, specifically among individuals immigrating from the Fujian Province in China, a group accounting for the majority of the recent wave of Chinese immigrants to New York City, and a group further marked by low rates of education and health care resources.

For AA communities, this significant health disparity is further exacerbated by the stigma associated with HBV infection and cultural barriers to seeking help.5,6 Cultural beliefs have been shown to have a significant effect on perceptions of illness and health management in all populations, particularly immigrant communities. Cultural beliefs and influences represent key factors in understanding health care choices and service use. Among Asian subgroups, there exists a strong sense of group collectivism—individuality is submerged in the interest of group welfare.7 In some Asian cultures, there is greater emphasis on self-help and informal help-seeking networks instead of the use of formal services.8–10 Friends, neighbors, and family are readily accessed and consulted before turning to formal services.7,8 The added stigma associated with HBV may create a situation in which many individuals delay seeking both informal and formal support and services. Given the cultural influences on health promotion and behavior and the relative isolation of new Asian immigrants, community institutions and leaders from the community are well-positioned to serve as cultural brokers or bridges to link immigrant community members to needed resources and sources of information and destigmatizing certain health conditions.11 Thus, community-based, culturally tailored interventions have been identified in several studies as an effective way to increase cancer screenings,12–16 improve diabetes management,17 increase access to mental health services,18 and accelerate smoking cessation19 in AA communities.

Community coalitions are recognized as a means to address health disparities, providing an opportunity to pool expertise, perspectives, and resources to develop and sustain innovative approaches to affect community health. Launched in 2004, the AAHBP is a coalition-driven initiative that led to the first comprehensive effort to decrease HBV disparities in AAs. Using Florin, Mitchell, and Stevenson’s Stages of Coalition Development framework,20 this article broadly examines the experience of implementing AAHBP and the lessons learned in developing a CBPR initiative for understanding and addressing HBV disparities in New York City. The framework includes the following stages: Initial mobilization, establishing an organizational structure, building capacity for action, planning for action, implementation, refinement, and institutionalization.20 We also trace the development and evolution of the AAHBP to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) REACH U.S. Center of Excellence in the Elimination of Health Disparities (CEED).21 The AAHBP was approved by the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Program Overview

Initial Mobilization Leading to AAHBP

The seeds for mobilization began in the 1990s with sporadic community-based screenings, initiated by community providers serving New York City’s Chinatown community and later by the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation (HHC). In 2001, the Charles B. Wang Community Health Center (CBWCHC) and the Chinese American Independent Provider Association mobilized a group of concerned individuals around the need for a community-based HBV screening and vaccination program. They approached the city council member representing the Chinatown District, who would prove to be a responsive champion to this cause. Regular meetings were held between 2001 and 2003 to discuss strategies to address and reduce HBV disparities. The group later expanded to include HHC and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH).

In December 2003, the council member and members of this coalition contacted the New York University Center for the Study of Asian American Health (CSAAH) to discuss collaboration. They recognized that vital to securing city council support for a broad-based HBV prevention initiative included having both community support and scientific credibility from a leading academic medical center. CBWCHC played a critical facilitating role as a founding partner of the community group and CSAAH.

During this time, the group formalized the AAHBP coalition and expanded to other members (Table 1). They expanded the initiative based on the initial proposal developed by the CBWCHC and the Chinese American Independent Provider Association to include a more comprehensive and costlier program that would provide screening, vaccination, evaluation, and treatment for those who were diagnosed, and the creation of a registry to capture epidemiologic data on HBV. The coalition submitted this proposal to the city council in early 2004. As a result of mobilization and advocacy efforts, the AAHBP garnered the support of several key council members and successfully obtained a multiyear, multimillion dollar award beginning in summer 2004 to support health education, outreach, vaccination, screening, patient treatment, laboratory and diagnostic testing, and a centralized clinical repository for HBV in New York City. This award established an outlet from which cost-effective, innovative, and targeted community health programs could be developed, tested, evaluated, and disseminated nationally.

Table 1.

Partnerships by Sector and Discipline of the Asian American Hepatitis B Program (AAHBP)

| Category | Organizational Partner |

|---|---|

| NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health*† | |

| NYU College of Dentistry | |

| NYU College of Nursing | |

| NYU School of Medicine Adult Infectious Disease* | |

| NYU School of Medicine Pediatric Infectious Diseases*† | |

| Healthcare Associations, Organizations, and Hospitals Centers |

Bellevue Hospital Center* |

| Charles B. Wang Community Health Center*† | |

| New York Downtown Hospital* | |

| Chinese American Independent Provider Association | |

| Chinese American Medical Society | |

| Community Healthcare Network | |

| Concorde Medical* | |

| Gouverneur Healthcare Services* | |

| New York City HHC | |

| Bronx Lebanon Hospital | |

| Membership Organizations and Community Partnership Groups |

Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations† |

| Chinese American Planning Council* | |

| Chinese Community Health Partnership | |

| New York City Viral Hepatitis Network*† | |

| Vietnamese Community Health Initiative | |

| Social Service and Other Nonprofit Agencies | African Services Committee |

| Alianza Dominicana | |

| American Cancer Society, Asian Initiative*† | |

| American Liver Foundation | |

| Caribbean Women’s Group | |

| El Puente | |

| Indochina Sino-American Community Center | |

| Korean Community Services of Metropolitan NY, Inc. † | |

| LOLA | |

| Mary Lea Richards Foundation | |

| Nigeria House | |

| Government Agencies | New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene*† |

| Office of the City Council of the City of New York*† | |

| Media Outlets | Admerasia, Inc. Korea Times |

| China Press New York News | |

| Chinese Consumer Weekly News Korea | |

| Compact Express News Ming Pao | |

| Daily Sport Seoul Pakistan News | |

| Desi Talk Pakistan Post | |

| India Abroad Sada-E-Pakistan | |

| India Bulletin Saesye Times | |

| India Express Sing Tao Newspaper | |

| Korea Central Daily World Journal Newspaper | |

| Corporate | Bristol-Myers Squibb |

| Gilead |

Founding member of AAHBP.

Current B Free CEED Partners.

Establishing The AAHBP Organizational Structure And Building Capacity For Action

Applying a CBPR Approach

Principles underlying CBPR22 were employed in the development of AAHBP. CBPR calls for the active and equal partnership of community stakeholders throughout the research process. Congruent with CBPR is the notion of building and sustaining community assets to promote health. AAHBP partners fostered insight into the development of an asset-based approach to HBV prevention.

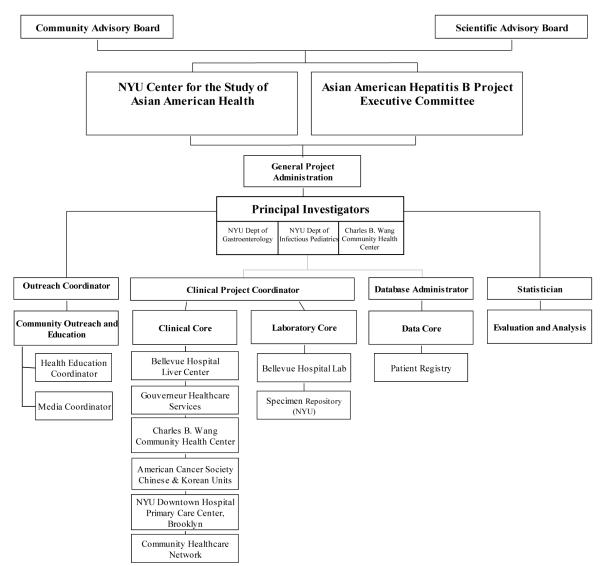

The first step was to develop an organizational infrastruc-ture (Figure 1). Given the collaborative nature of the initiative the AAHBP partners decided that the work would be guided by three principal investigators, with one of the principal investigators being a community partner. Consensus was made to centralize coordination at CSAAH and to convene an executive committee composed of representatives from the AAHBP coalition. The executive committee was composed of three community representatives, five individuals representing the hospital partners, and three individuals from HHC and New York City DOHMH. A program director was hired to facilitate the administration and coordination of the program across different partners with the principal investigators. Two advisory boards were established, the scientific advisory board and the community advisory board. Both boards provided guidance and recommendations to the executive committee. Subcommittees were eventually established to address specific program aspects (from outreach, screening, vaccination, and treatment). Representatives were designated by each organization to communicate issues and relay progress to the program director. The program director met weekly with the principal investigators to discuss all facets of the program, to develop an in-depth implementation plan and to resolve conflicts and problems. Open-ended meetings with all coalition members were held semi-annually to discuss progress and problems, report results, and plan for the following program year.

Figure 1.

Asian American Hepatitis B Program (AAHBP) Organizational Chart

Planning for Action

The key motto underlying AAHBP was and remains: “From the community, by the community, to the community.” With input from all partners, AAHBP’s model program included a multi-pronged approach consisting of the following components: (1) Outreach and education; (2) screening; (3) vaccination; (4) follow-up evaluation and treatment; (5) program evaluation and data analysis; and (6) policy and advocacy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Asian American Hepatitis B Program (AAHBP) Model

| Deliverables | Guiding Plan |

|---|---|

| Outreach and Education | To raise awareness of HBV to AAs by conducting an aggressive multimedia campaign and to provide culturally and linguistically tailored educational interventions. |

| Screening | To identify individuals who are either HBV-infected or at risk through the provision of culturally and linguistically relevant no-cost screenings to APIs at multiple community-based sites throughout New York City. |

| Vaccination | To offer no-cost HBV vaccination to uninsured individuals found to be susceptible to HBV infection. |

| Follow-Up Evaluation and Treatment |

To provide comprehensive cultural and linguistically relevant no-cost specialist evaluation and treatment to those determined to be infected with HBV. |

| Program Evaluation and Data Analysis |

To maintain an extensive HBV registry for program evaluation, epidemiologic studies, and evaluation. |

| Policy and Advocacy | To conduct an economic analysis examining the cost-benefits and cost-effectiveness of the program to inform and integrate health policy and advocacy on HBV prevention at all stages of program development. |

The AAHBP dedicated the first 6 months to prioritizing goals, putting processes into place, and developing operational protocols. This left 6 months for AAHBP to accomplish its year 1 deliverables. This intensive planning period dedicated to developmental tasks fostered a shared vision and plan to address HBV disparities and a greater sense of ownership and investment in AAHBP, which was crucial to successfully accomplishing the educational, screening, vaccination, and treatment goals for year 1.

Implementation and Refinement

In years 1 through 3, the AAHBP launched an intense city-wide, multimedia, multilingual educational campaign. The AAHBP focused primarily on Chinese and Korean Americans in years 1 and 2 with the allocation of resources determined by disease burden. In year 3, the program was expanded to address the needs of other Asian ethnic groups (South and Southeast Asians) and to other populations with high HBV rates (African, Afro-Caribbean, Eastern European, and Latino communities). The expanded program was called, BFree NYC, although the AAHBP continued to remain the dominant component. Media campaigns were expanded to target the new groups. By the end of year 4, AAHBP/BFree NYC had educated approximately 11,000 individuals through workshops, screened more than 8,900 individuals for HBV, administered 5,800 doses of vaccine to susceptible persons, and clinically evaluated nearly 1,200 screening participants identified with HBV.

At the community level, AAHBP findings were disseminated on 20 radio programs and more than 650 articles in over 25 ethnic newspapers with a total estimated reach of greater than 1,000,000 individuals in the metropolitan New York City area. AAHBP also reached the community through educational videos, televised public service announcements, and a special documentary feature on HBV on the public broadcasting station. The program built capacity of clinicians, advocates, and students to address HBV in the Asian community by providing a series of educational workshops. AAHBP has presented its work in nearly 30 national and local conferences. Preliminary clinical results were published in the CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in 2006.1 Findings have also informed a disease model that simulates HBV disease progression for a cost-effective analysis of early stage treatment compared with late-stage treatment.23

Program evaluations revealed a great demand in the AA community for AAHBP’s culturally and linguistically appropriate services. This was supported by the consistently high participant turn out at screening events and levels of satisfaction reported on participant surveys. AAHBP’s partnership was effective in reaching the targeted communities.

Institutionalization and Sustainability

The city council funding aided AAHBP in creating a cohesive, effective, multisite, multi-ethnic, community-level program. By year 4, AAHBP had encompassed a diverse range of organizational partners (Table 1). From the outset, however, it was evident that the city could not continue the level of funding beyond the first 4 years. In year 4, AAHBP made efforts to partner directly with the New York City DOHMH and to move from mass screening events to the establishment of free, culturally sensitive drop-in clinics in each New York City borough where persons at risk could be screened and vaccinated and infected persons could be referred to specialized community clinics, but was unable to gain the DOHMH’s support.

AAHBP dramatically shifted to a minimal level operation by the end of year 4, often with in-kind, program staff from the participating organizations working together to maintain the coalition. With the change in the current economic climate, AAHBP has struggled to secure resources to support community-based, culturally relevant screening and vaccination services at low or no cost. Post-funding, the AAHBP hospital clinics were reorganized and integrated within existing clinics and a sliding scale fee offered to chronically infected individuals.

A difficult challenge has been managing community expectations for sustaining the work. City council funding for AAHBP was significant and community-based organizations (CBOs) were compensated for providing services that largely did not exist before the award. Many of the CBO partners and the lay community had come to rely on the services being offered. Although the AAHBP continues to garner additional funds for screening and vaccination services, the scale of the funding is significantly less than the city council award. Moreover, these funds have been restricted to HBV screening and vaccination and do not support treatment activities for those already infected.

To ensure sustainability, AAHBP has focused on the following avenues: Policy, dissemination, and grant development. AAHBP actively engaged in policy initiatives, working closely in year 3 with the National Hepatitis B Taskforce on the Hepatitis B Bill (HR4550) in congress and in year 4 on a New York City Council resolution to support HBV screening for high-risk communities in New York City.

Active community participation, grant writing efforts, educational awareness, and sheer partner commitment have supported sustainability and continued core screening, vaccination, research, and dissemination activities. AAHBP has followed a two-prong approach of obtaining funding to support: (1) Coalition development, program infrastructure, and clinical and direct service activities through foundations and pharmaceutical agencies; and (2) research, policy development, training, and dissemination through federal and state funding mechanisms.

Extending The Reach: AAHBP To CEED

AAHBP partners continue to seek funds to support screening and vaccination activities; funding for such activities, how-ever, have been uniformly decreasing across the United States. Instead, AAHBP began to more actively pursue the second approach concentrating on more policy and disseminated-related activities. By the end of year 4, AAHBP was able to leverage its accomplishment and earned the designation as a CDC CEED. Guided by the original AAHBP partners, BFree NYC CEED’s mission is to serve as a national resource and expert center on the elimination of HBV health disparities among AA and NHPI communities, with the goal to develop, evaluate, and disseminate multilevel, evidence-based best practices and activities. B Free CEED has a three-pronged approach to achieve this goal:

Raise awareness about HBV among all stakeholders

Identify evidence-based best practices for

Identification of the chronically infected.

Outreach and vaccination for individuals who are at risk of infection.

Provision and access to treatment and care for the chronically infected.

Ensure sustainability and reach of evidence-based activities and practices through

Capacity building and collaborations through partnerships and coalitions.

Dissemination of evidence-based strategies and practices.

Advocacy for policy- and systems-level efforts in support of best practices to eliminate HBV-related disparities affecting AAs and NHPIs.

The BFree CEED is identifying best practices based on the experience, success and lessons learned from AAHBP.8,24 For example, the AAHBP database is being analyzed to identify best practices for identifying and reaching chronically infected and individuals at risk for HBV. Furthermore, the BFree CEED coalition member, CBWCHC, is working to develop a collaborative care model for HBV based on experience gained from the linkage to care component of AAHBP. Other initiatives rooted in AAHBP include the development of a citywide HBV coalition in partnership with the New York City DOHMH, and the continued work to introduce a city council resolution on HBV screening for at-risk communities.

Accomplishments, Challenges, And Lessons Learned

AAHBP has been the first and most successful comprehensive program to address the problem of HBV in the Asian community in the United States. Almost 9,000 persons have been tested, more than 1,200 persons have benefited by access to care and treatment, and several thousand persons have been protected by immunizations. AAHBP findings have informed the new CDC HBV screening guidelines released in September 2008,2 and has been cited in the Institute of Medicine Report, Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of HBV and C.3

AAHBP has identified a number of challenges during the course of its development, including (1) reconciling agendas and competing tensions across organizational partners, (2) managing a deliverables-based budget, and (3) balancing action and research. Different strategies were developed to address these challenges and to ensure program continuity and a high-quality of coordination of services (Table 3).

Table 3.

Challenges and Solutions in Developing the Asian American Hepatitis B Program (AAHBP)

| Challenges | Strategies to Overcome Challenges |

Specific Examples and Steps Taken to Address Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Creating shared vision and framework |

|

Five active community-based partners representing a considerable range of expertise/ interests from various academic disciplines, each had a unique vision of how the project should unfold. Partners all participated in creating a shared vision and outlining the framework and core services of the program. The program director’s extensive experience in negotiating across cultures and agendas was key to facilitating group discussions and overcoming this challenge. |

| Transitioning from coalition to program |

|

At the outset, decisions were made in a large group resulting in slow and cumbersome decision making. To streamline the process, smaller, more manageable task forces that included community, researchers, and clinicians with specific responsibilities were created within the coalition. |

| NYU served as the lead coordinating agency, centralizing all resources that were disbursed to partners according to jointly-developed Memorandum of Understanding (MOUs). Centralizing all activities ensured consistency in program development, implementation, and reporting, as well as continuity of services. The program director was placed at NYU to coordinate all aspects of the program and serve as the liaison with the City Council and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (New York City DOHMH). |

||

| Negotiating roles and responsibilities |

|

Roles and responsibilities were defined through joint participation in the development and implementation of the protocols. Jointly developed MOUs outlining the nature of their responsibilities and their compensation were signed by program partners. This process ensured shared understanding of expectations and program objectives. |

| Recognizing the “devil in the details” |

|

AAHBP activities were conducted at multi-site community-based sites all across New York City. It was critical that the program created rigorous quality assurance and program protocols before implementation. Six months of concerted planning with all partners was invested at the start of the program to identify potential challenges and barriers in all aspects of program development, from outreach, education, recruitment, screening, vaccination, referral, and treatment. A standardized implementation and quality assurance protocol was systemically created for each area. Core AAHBP staff and an external evaluator (assigned by the funder), visited each site to observe and monitor program activities and data collection. |

| Although each site provided data, the core repository was centralized at NYU. AAHBP staff extensively conducted chart-reviews and data cleaning on an ongoing basis to immediately identify discrepancies and potential challenges. AAHBP program staff centrally developed all core outreach and educational messages in collaboration with input from community partners and a advertising consultants to ensure cultural and language relevance. |

||

| Balancing the tension between service and research components |

|

Two thirds of the city council funds were primarily dedicated to the service components of the AAHBP grant for vaccination, screening, and treatment costs. Academic partners felt the opportunity to amass a significant data set that captured several clinical points in time on underrepresented communities in clinical research was important, while community partners stressed the service component of the program. |

| The use of CBPR principles played a critical role in balancing the tension between service and research components and goals. Strategies that addressed the challenge required a co-learning process of partners’ needs, agendas, and priorities and the recognition that all partners would participate in all areas of service and research components. |

||

| Competing tensions with the city health department and the AAHBP |

|

New York City DOHMH was assigned as the fiscal conduit for AAHBP. New York City DOHMH and AAHBP had differing priorities in regards to HBV prevention and treatment. |

| To increase New York City DOHMH support for the program, there were ongoing meetings and discussions, in addition, AAHBP worked closely with New York City DOHMH’s external program evaluator to ensure transparency of program activities, development of core deliverables, and appropriate expenditures. |

Coalition building has been crucial to AAHBP development, fundraising, and public outreach for AAHBP. AAHBP began with a coalition of CBOs working closely with an academic center, which led the coordination and advocacy efforts. CSAAH served as the institutional vehicle for the city council to allocate substantial funding for the community-based initiative. The community partners were instrumental in garnering the political and community support needed for the initiative to be supported by both the New York City offices of the city council and the mayor. These partners also played a significant role in ensuring high recruitment and retention rates.

Although each community partner had considerable experience working within their own communities, the pan-Asian element of the project required that organizations serving different Asian ethnic groups work closely together to develop a shared vision and a common approach for HBV prevention. For example, CBWCHC serves predominantly the Chinese American community, and Korean Community Service is a social service agency targeting Korean-American communities in New York City. These distinct Asian ethnic groups have different cultural and language needs, which had to be accounted for when developing an overall model for this program.

Reconciling Agendas

There were five partners actively engaged in all phases of the program, representing difference perspectives and constituencies. Consequently, there was the challenge of integrating and managing organizational agendas and competing priorities. Although the coalition agreed on the essential elements of a comprehensive HBV prevention program, there were different issues that had to be negotiated, including how these elements were operationalized and the amount of resources allocated to different partners. A common tension reflected in community engagement partnerships concerns funding, which served as a challenge between academic and community partners, and among community partners themselves. The program director’s extensive experience in facilitation and consensus building was critical in overcoming the challenge of balancing and integrating different perspectives to develop sound protocols for program components.

Managing a Deliverables-based Budget

The magnitude of the funding presented a substantial challenge as the coalition transitioned from mobilization and advocacy to delivering programmatic activities within a relatively short period of time because the grant from the New York City Council followed the city’s fiscal year. Although multiyear funding was awarded to the program, the amount allocated per year was drawn down, and there were few opportunities for carryover. To complicate matters, all partners received reimbursement for activities long after the project year was completed and was contingent upon partners agreeing to front considerable resources to support activities. Unlike a traditional grant award that provides for personnel services and otherthan-personnel services, this grant was a “deliverables-based” grant. Therefore, the program and its partners did not receive grant monies until all projected outputs or deliverables were produced. For example, instead of receiving grant money for a phlebotomist, the partners received money for each person screened. Program partners completed a memorandum of understanding, which outlined the nature of their responsibilities and the manner of compensation.

Balancing Research and Action

There was a strong need to balance action and research. Community partners wanted timely dissemination of findings; however, adhering to scientific protocols required considerable time between implementation, evaluation, and dissemination efforts. All screening and follow-up data were entered by the respective community partners. Each of these partners was given password-protected access to their sites database. Partners were encouraged to analyze their data and disseminate the findings to the community and by taking the lead in developing manuscripts for publication in professional public health journals. Given that the data was being collected and entered in various community settings, it was difficult to maintain rigorous protocols. This necessitated additional time being spent in the process of cleaning and coding the dataset, which affected the timely dissemination of publications in peer-reviewed publications. Moreover, it became evident that more time and resources were needed to support and build the capacity of community partners to lead or be actively engaged in the writing process.

Conclusion

Grassroots community organizing and academic–community partnerships that address significant health disparities can be successful in providing needed services and contribute to our current knowledge. It requires developing clearly defined and shared goals, effective leadership, constant partnership nurturing, and perseverance to overcome the challenges common to all such endeavors. Understanding a coalition’s stages of development and planning can inform similar efforts across the country for the prevention of HBV and other health disparities.

Acknowledgments

For a manuscript of this nature, there are many wonderful individuals and organizations that must be acknowledged. First, we want to thank our community and organizational partners listed in Table 1 whose commitment and dedication to addressing HBV inspiring.

The authors thank the AAHBP Coalition for their substantial support in the development of AAHBP’s shared vision and framework, goals, and activities. We are deeply indebted to the New York City Office of the City Council, in particular the Honorable Alan J. Gerson, for mobilizing the coalition and bringing together partners from various sectors, disciplines, and organizations to address HBV disparities. We also acknowledge the key support of New York City Council members John Liu, Christine Quinn, Robert Jackson, Melinda Katz, and Joel Rivera, for their instrumental role in garnering city council support for the AAHBP. In the early years, we appreciated the support of Ben Chu, MD, MPH, and Benjamin Mojica, MD, of the New York City HHC.

Leadership of the AAHBP Coalition and Program included the following individuals: Thomas Tsang, MD MPH, Henry Pollack, MD, Alex Sherman, MD, Hillel Tobias, MD, PhD, Mariano Jose Rey, MD, Mary Ruchel Ramos, MA, Douglas Nam Le, and Chau Trinh-Shevrin, DrPH. We also appreciate the efforts of core program faculty and staff from Charles B. Wang Community Health Center (Alan Tso, MD, Kevin Lo, MPH, Perry Pong, MD, Su Wang, MD, Shao-Chee Sim, PhD, Christina Lee, MA), Korean Community Services (Jinny Park, Kay Chun, MD, Eunjoo Chung, MSW), American Cancer Society (Ming-der Chang, PhD, Arlene Chin), Gouverneur Healthcare Services (Pearl Korenblit, William Bateman, MD, David Stevens, MD, Mendel Hagler, MD), Bellevue Hospital Center (Chris Cho, Edith Davis, Vinh Pham, MD, Eric Manheimer, MD, Judy Aberg, MD, Helene Lupatkin, MD, Gerald Villaneuva, MD, Andrew Miller, MD, Michael Phillips, Cecilia Thang, Yvonne Ho, Chun Wong), New York Downtown (Eric Poon, MD, William Wang, Waiwah Chung, RN, and Charles Ho), Community Healthcare Network (Kameron Wells, ND, Catherine M. Abate, JD, Gloria Leacock, MD) and NYU (Keija Wan, MPH, Sindy Yiu, Ming-Xia Zhan, Paige Baker, Rona Luo, Jenny Bute, Chia-hui Peng, MPH, John Nolan, Neetu Sodhi, Madeline Kahn, and Eduardo Betancourt), and Allison Stark, MD. The AAHBP Coalition also wants to thank the many countless individuals who offered their time and assistance in outreach and health screening events, survey administration and data collection/entry efforts.

We also acknowledge the role of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene in the oversight and evaluation of AAHBP, in particular Mary Bassett, Jackie Kellahan, Jane Zucker, Stephen Friedman, Isaac Weisfuse, and Kevin Mahoney. We appreciate their present efforts to move towards improving access to HBV screening and vaccination.

This publication was made possible by Grant Numbers P60 MD000538 (NCMHD) and U58DP001022 (CDC) and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCMHD and the CDC. A grant from the New York City Office of the City Council supported the program development and disseminations efforts of the Asian American Hepatitis B Program.

The authors thank Rebecca Park for her tireless energy and hard work in assisting with the development and submission of this manuscript. We also thank Laura Wyatt, MPH, and Greta Elysée for their assistance.

References

- 1.Pollack H, Wan K, Ramos R, Rey M, Sherman A, Tobias H, et al. Screening for chronic hepatitis B among Asian/ Pacific Islander populations – New York City, 2005. MMWR. 2006;55:505–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, Wang SA, Finelli L, Wasley A, et al. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR. 2008;57:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine . Hepatitis and liver cancer: A national strategy for prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. The National Academies Press; Washington (DC): 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Bureau of the Census . American Community Survey. U.S. Bureau of the Census; Washington (DC): 2007. Data derived from analysis by the Asian American Federation Census Information Center. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Speigel BMR, Bollus R, Han S, et al. Development and validation of a disease-targeted quality of life instrument in chronic hepatitis B: The hepatitis B quality of life instrument, version 1.0. Hepatology. 2007;46:113–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.21692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran TT. Understanding cultural barriers in hepatitis B virus infection. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(Suppl 3):S10–3. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76.s3.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esperat MC, Inouye J, Gonzalez EW, Owen DC, Feng D. Health disparities among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2004;22:134–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi D, Hwang WC. Predictors of help-seeking for emotional distress among Chinese Americans: Family matters. J Counsel Clin Psychol. 2002;70:1186–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narikiyo T, Kameoka V. Attributions of mental illness and judg ments about help-seeking among Japanese-Americans and White-American students. J Counsel Psychol. 1992;39:363–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin J. Help-seeking behaviors by Korean immigrants for depression. Issues Mental Health. 2002;23:461–76. doi: 10.1080/01612840290052640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin JJ, Mantell J, Weiss L, Bhagavan M, Luo X. Chinese and South Asian religious institutions and HIV prevention in New York City. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(5):484–502. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.5.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh JME, Salazar R, Nguyen TT, et al. Healthy colon, healthy life: A novel colorectal cancer screening intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee H, Kim J, Han H-R. Do cultural factors predict mammography behaviour among Korean immigrants in the USA? J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(12):2574–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen T-UN, Kagawa-Singer M. Overcoming barriers to cancer care through health navigation programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24(4):270–8. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu T-Y, West B, Chen Y-W, Hergert C. Health beliefs and practices related to breast cancer screening in Filipino, Chinese and Asian-Indian women. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30(1):58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson J Carey, Taylor VM, Chitnarong K, et al. Development of a cervical cancer control intervention program for Cambodian American women. J Community Health. 2000;25(5):359–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1005123700284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C-Y, Chan SMA. Culturally tailored diabetes education program for Chinese Americans: A pilot study. Nurs Res. 2005;54(5):347–53. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallagher-Thompson D, Wang P-C, Liu W, et al. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational skill training DVD program to reduce stress in Chinese American dementia caregivers: Results of a preliminary study. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(3):263–73. doi: 10.1080/13607860903420989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu D, Ma GX, Zhou K, Zhou D, Liu A, Poon AN. The effect of a culturally tailored smoking cessation for Chinese American smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(12):1448–57. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Florin P, Mitchell R, Stevenson J. Identifying training and technical assistance needs in community coalitions: a developmental approach. Health Educ Res. 1993;8(3):417–32. doi: 10.1093/her/8.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Internet] [updated 2010 May 13; cited 2010 Dec 14];National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promo tion: REACH U.S. Grantee Partners. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/reach/reach_us.htm.

- 22.Trinh-Shevrin C, Islam N, Tandon SD, Abesamis N, Ho-Asjoe H, Rey MJ. Using community-based participatory research as a guiding framework for health disparities research centers. Prog Commun Health Partnersh. 2007;1(2):195–205. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Post SE, Sodhi N, Peng C-H, Wan K, Pollack HJ. A simulation shows that early treatment of chronic hepatitis B infection can cut deaths and be cost-effective. Health Aff. 2011;30(2):340–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.B Free CEED: National Center of Excellence in the Elimination of Hepatitis B Disparities [Internet] [updated 2010; cited 2010 Dec 14];New York University School of Medicine Institute of Community Health & Research. Available from: http://hepatitis.med.nyu.edu.