Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an uncommon cause of community-acquired pneumonia in immune-competent hosts. It is commonly seen in patients with structural lung abnormality such as cystic fibrosis or in immune compromised hosts. Here, the authors report a case of community-acquired Pseudomonas pneumonia in a 26-year old healthy man who presented with 8-week history of malaise and cough.

Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a rare cause of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in an immune competent host. The majority of patients with Pseudomonas CAP have a predisposing factor such as structural lung disease, immunodeficiency syndrome, neutropenia, cytotoxic drug use or prolonged antibiotic intake.1 Cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis,and chronic obstructive lung disease are typical lung diseases rendering patients vulnerable to Pseudomonas pneumonia.2 There is no characteristic imaging finding among patients with Pseudomonas pneumonia. Bilateral infiltrates consistent with bronchopneumonia, cavitary pneumonia, pleural effusion and nodular infiltrates are more common.3 4 Here, we report a case of 26-year-old man whose initial presentation and x-ray findings were suggestive of other differential diagnoses but P aeruginosa CAP.

Case presentation

He was a 26-year-old otherwise healthy man presented with a 8-week history of cough, intermittent fever, bone pain and malaise. Initially, the cough was dry but finally it produced scant yellow-green sputum. He did not complain of any dyspnoea, chest pain or haemoptysis. He also denied chills and night sweats. He remained symptomatic despite frequent outpatient managements. He was married, never smoked, but worked as a technician in a dairy product factory. Serologic tests of brucellosis were also negative. He had no memory of hot tub exposure. He had no history of previous hospitalisation or recent antibiotic use.

His medical and family histories were unremarkable.

Investigations

On physical examination, he was reasonably well and not febrile; the blood pressure was 100/65 mm Hg, the heart rate 105 beats per min and the respiratory rate 16 breaths per min with oxygen saturation of 96% on room air. There were coarse inspiratory crackles in left lung. The remainder of whole body examination was normal.

Serum levels of electrolytes, glucose, albumin, total protein, calcium and phosphorus were all normal. Tests of thyroid, liver and renal function were normal. There was mild normocytic, normochromic anaemia. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 74 mm/h. Total leucocyte count was normal except monocytosis. Testing for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies were negative.

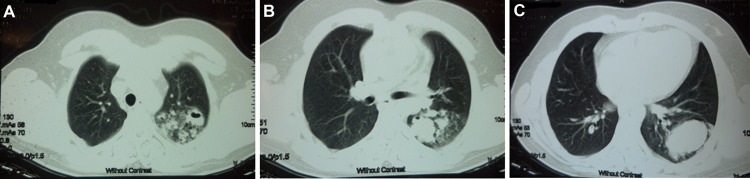

CT of the chest revealed a left upper lobe air-space consolidation with foci of necrosis extending inferiorly into a mass-like lesion in left lower lobe. No characteristic finding of bronchiectais was found (figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A–C) Sections of lung CT scan showing air-space consolidation with necrosis and air-bronchogram on left upper lobe extending inferiorly to a mass-like lesion in left lower lobe.

Tuberculosis was a concern but tuberculin skin testing was not reactive. Staining 3 sputum specimens were negative for acid-fast bacilli. Bronchoscopic examination and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of left upper and lower lobe were performed. Cultures of the BAL grew Klebsiella pneumonia sensitive to ofloxacin. Simultaneously, blood cultures were sterile. BAL staining for acid-fast bacillus was negative. The results of mycobacterial cultures were pending.

Differential diagnosis

Based on constellation of symptoms, anaemia, increased rate of erythrocyte sedimentation and monocytosis, differential diagnosis consisted of non-resolving pneumonia, mycobacterial infection; especially tuberculosis, lung cancer and lymphoma. Other diagnoses as bacterial endocarditis or an autoimmune disorder were less probable.

Treatment

He was commenced on ofloxacin. During the next week, he was still symptomatic. The cough remained and produced moderate amount of yellow-green sputum so he was planned for CT-guided biopsy of the left lower lobe pulmonary mass.

Outcome and follow-up

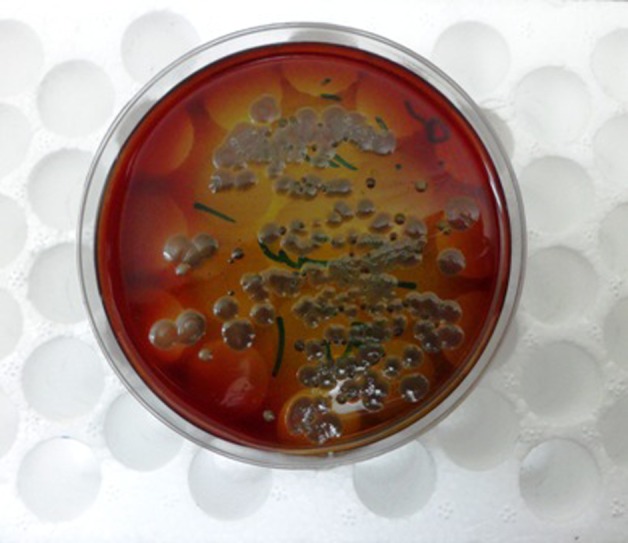

On CT-guided biopsy, 6 cc purulent fluids were aspirated, otherwise there was no discrete parenchymal mass. Cultures of the aspirated fluids grew mucoid P aeruginosa (figure 2) sensitive to ciprofloxacin. Chest x-ray, performed the following day, revealed no remnant of previous mass-like lesion. He was discharged and administered a ciprofloxacin-based regimen for 2 weeks. At 6-week follow-up visit, all the presenting symptoms including bone pain and cough resolved as well as anaemia, monocytosis and high sedimentation rate.

Figure 2.

Large colonies of mucoid Pseudomonas grew on culture media.

Two months later, testings for mycobacterial growth including sputum, BAL and aspirated fluids were negative. He was asymtomatic and chest x-ray showed complete resolution of previous infiltrates. In addition, levels of immune globulins and complements, assays of HIV and sweat chloride test showed no predisposing condition for P aeruginosa CAP.

Discussion

Non-mucoid strains of P aeruginosa are ubiquitous in the environment. Folliculitis, external otitis and puncture wound infections are examples of Pseudomonas infections. However, there are very few case reports of Pseudomonas CAP in healthy immune-competent hosts. Person-to-person transmission or inhalation of infected aerosols via exposure to hot tub, swimming pool, whirlpool spa are potential routes of disease acquisition. For instance, Andes et al, reported a case of severe necrotising Pseudomonas pneumonia in a healthy 40-year-old man infected during a personal-use hot tub exposure.5 The disease presents clinically in a similar manner to other CAPs, the majority of patients have acute respiratory complaints, but based on the review done by Hatchette et al, there are reports of patients presenting with sub acute or chronic illness. Pneumonia involved right upper lobe in two-third of patients but any lobe may be involved. It may progress to cavitary pneumonia or a lung abscess.6

Due to rarity of the disease entity and lack of randomised clinical trials, the optimal treatment of Pseudomonas CAP in a healthy host is not defined. Whether to choose combination therapy or monotherapy is controversial. Many prefer treating patients with a combination of antiPseudomonas antibiotics such as ticarcillin-clavulanate, imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem and ciprofloxacin.7

Mucoid strains of P aeruginosa are almost entirely found in patients with cystic fibrosis, so their isolation from the lung mandates a timely investigation to diagnosis an unidentified cystic fibrosis.8 The result of sweat chloride testing was not suggestive of cystic fibrosis, although the patient refused to undergo further testing.

Learning points.

Pseudomonas may cause CAP in an otherwise healthy host.

Pseudomonas CAP may present with a subacute course and clinical features similar to mycobacterial pulmonary infections.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Fujitani S, Sun HY, Yu VL, et al. Pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: part I: epidemiology, clinical diagnosis, and source. Chest 2011;139:909–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arancibia F, Bauer TT, Ewig S, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia due to gram-negative bacteria and pseudomonas aeruginosa: incidence, risk, and prognosis. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1849–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winer-Muram HT, Jennings SG, Wunderink RG, et al. Ventilator-associated Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia: radiographic findings. Radiology 1995;195:247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah RM, Wechsler R, Salazar AM, et al. Spectrum of CT findings in nosocomial Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. J Thorac Imaging 2002;17:53–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crnich CJ, Gordon B, Andes D. Hot tub-associated necrotizing pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:e55–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatchette TF, Gupta R, Marrie TJ. Pseudomonas aeruginosa community-acquired pneumonia in previously healthy adults: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:1349–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Traugott KA, Echevarria K, Maxwell P, et al. Monotherapy or combination therapy? The Pseudomonas aeruginosa conundrum. Pharmacotherapy 2011;31:598–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doggett RG, Harrison GM, Wallis ES. Comparison of some properties of pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from infections in persons with and without cystic fibrosis. J Bacteriol 1964;87:427–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]